1 Introduction

Chaotic systems are dynamical systems whose apparently random or unpredictable behavior is governed by underlying patterns and deterministic laws that are highly sensitive to initial conditions.

Their implementations have been studied during the last decades [6].

The sensitivity of chaotic systems to parameters and initial conditions is considered for many real-world applications, ranging from data encryption, secure communication power systems, biology, circuit theory, and control, such as is mentioned in [25].

Fractional calculus incorporates a degree of freedom to dynamical systems.

This discipline’s principal and most attractive attribute is its ability to accurately describe and model real behavior compared to traditional integer-order models [22, 27, 18].

In addition, it has some advantages in characterizing systems considering memory factors [21].

The first mention of the possibility of a derivative of non–integer (arbitrary) order was raised between Leibniz and L’Hôpital in 1695.

Leibniz and L’Hôpital discussed the meaning of a half–order derivative and its consequences. Nowadays, that branch of mathematics is more than 300 years old.

Recently applications in different fields have shown the importance of fractional calculus [15]; some of the most important include earthquake and vibration engineering, automatic control, image and signal processing, bioengineering, arrhythmia discrimination, and chaotic dynamics [18, 5].

These studies typically have considered fractional order constant operators, including the Grünwald–Letnikov (GL), Caputo (C), and Riemann–Liouville (RL) definitions, as mentioned in [22].

According to [17], when initial conditions are homogeneous, the systems described by the definitions of GL, C, and RL coincide.

So they can be analyzed with Caputo or RL, and their results can be simulated with GL.

Although, until now, formalism can solve some relevant physical problems, it can not consider important classes of physical issues where the order itself is a function of the dependent or independent variables.

For instance, in [4] was found that the reaction kinetics of proteins exhibit relaxation mechanisms, which can be appropriately described by temperature-dependent fractional order. Additionally, the inherent characteristics of reaction kinetics (acquired by order of relaxation mechanisms) vary with temperature.

Therefore, it is reasonable to consider that a differential equation with an operator that updates its order as a function of temperature will better describe protein dynamics. This simple example shows that there are categories of physical problems where the variable-order fractional derivatives can better explain the phenomenon.

The Variable-Order (VO) fractional operator can be considered a natural analytical extension of fractional-order constant operators. Variable-order fractional derivatives can describe the properties of memory that change with time or the spatial location of dynamical systems.

There is interest in this subject since it allows a more accurate description of dynamic systems. The first definitions of these operators were given by [16]. As reported by [11, 29], the study of variable-order fractional calculus has become a hotspot in recent years.

In [8] is documented the effectiveness of using a dynamic integrodifferential operator of variable-order for viscoelastic and elastoplastic spherical indentation cases.

Furthermore, the dependence of the order function on the strain and strain rate of viscoelastic material was evaluated in [7].

Lorenzo and Hartley [10] investigated the concept of VO integration and differentiation and created meaningful definitions for VO integration and differentiation. They also presented two forms of order distributions with applications to dynamic processes.

Coimbra and Diaz in [2, 3] investigated the dynamics and control of a nonlinear viscoelasticity oscillator via VO operators.

Kobelev et al. investigated statistical and dynamical systems with fixed and variable memories, with the fractal dimensión of the system being variable with time and spatial coordinate [9].

Pedro et al. studied the motion of particles suspended in a viscous fluid with drag force determined using the VO calculus [13].

Recently, [23] discussed the mathematics of variable-order fractional calculus in perspective by examining possible applications of this topic in chaotic behaviors.

Synchronization is a phenomenon that may occur when two or more systems have time correspondence [28].

In contrast to the synchronization between variable-order chaotic systems, the chaotic synchronization (between integer-order and fractional order systems) has received increasing attention after the result of Pecora and Carroll.

In 1990, Pecora and Carroll synchronized two identical chaotic oscillators with different initial conditions for the first time [12].

Many control techniques are applied to the synchronization problem (which can also be seen as a trajectory tracking problem), including the sliding mode approach, projective synchronization method, output feedback synchronization method, active control method, and robust control, among others [24, 19].

The notion of synchronization of chaos has become an important research área in nonlinear science, not only for understanding the complicated phenomena in various fields but also due to its potential applications, especially in secure communication and image encryption, as mentioned in [14].

Then, we present a variable-order hyperjerk chaotic system that exploits the inherited legacy of fractional calculus to generate an abundant complex behavior.

Grünwald-Letnikov’s definition performs the numerical solution of the variable-order fractional chaotic systems. The dynamic behavior is analyzed using bifurcation diagrams and phase portraits. Additionally, the concept of “short memory” is employed.

The variable-order is defined using a periodic function, which leads to abundant chaotic dynamics. Finally, the active control technique is explored to achieve synchronization and ensure that the states track the desired trajectory of chaotic systems.

The current paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we give a brief introduction of Grünwald–Letnikov’s derivative definition and show the numerical method (algorithm) of variable-order fractional chaotic systems.

In Section 3, we introduce the variable-order fractional hyperjerk system and illustrate the chaotic behavior of the system showing its bifurcation diagram and phase plane.

In Section 4, we study the synchronization of the variable-order fractional chaotic systems via active control. In Section 5, the results are presented. Finally, in Section 6, conclusions are offered.

2 Grünwald–Letnikov Variable-Order Derivative

Fractional calculus deals with the use of derivatives and integrals with non-integer order (arbitrary), denoted by:

where

This paper considers Grünwald-Letnikov’s definition. In that manner, for numerical solution, the Grünwald-Letnikov explicit method for variable-order fractional differential equations is adopted. It is well known that the first integer-order derivative of a function

In general, the

where

By substituting

The Grünwald-Letnikov derivative definition for

Subsequently, according to [20] the Grünwald-Letnikov variable-order fractional derivative is defined by:

where

2.1 Grünwald–Letnikov Numerical Method

Reference [17] was devoted to the numerical treatment of fractional-order differential equations; based on the Grünwald–Letnikov definition of fractional derivatives, considering finite difference schemes to approximate the solution of fractional-order derivatives.

According to [17], the numerical formula to solve the fractional-order differential equation can be presented explicitly as:

where

Then, the numerical formula to solve the variable-order fractional differential equation in the explicit case in the sense Grünwald-Letnikov is defined as follows:

3 Variable-Order Fractional Hyperjerk System

An interesting hyperjerk system was recently proposed in [25]. That system is described as follows:

where

Here,

To conduct the fractional-order system (10)-(13) to generate chaotic behavior, it needs to add a nonlinear function

In this work we use the following function

In order to illustrate the chaotic behavior in the system, the following parameters are set

The roots of equation (18) are

Figure 1 shows the bifurcation diagram for the fractional order

The Fig. 1, confirms that the system (14)-(17) presents complex behaviors, ranging from period-1 to chaos in the interval

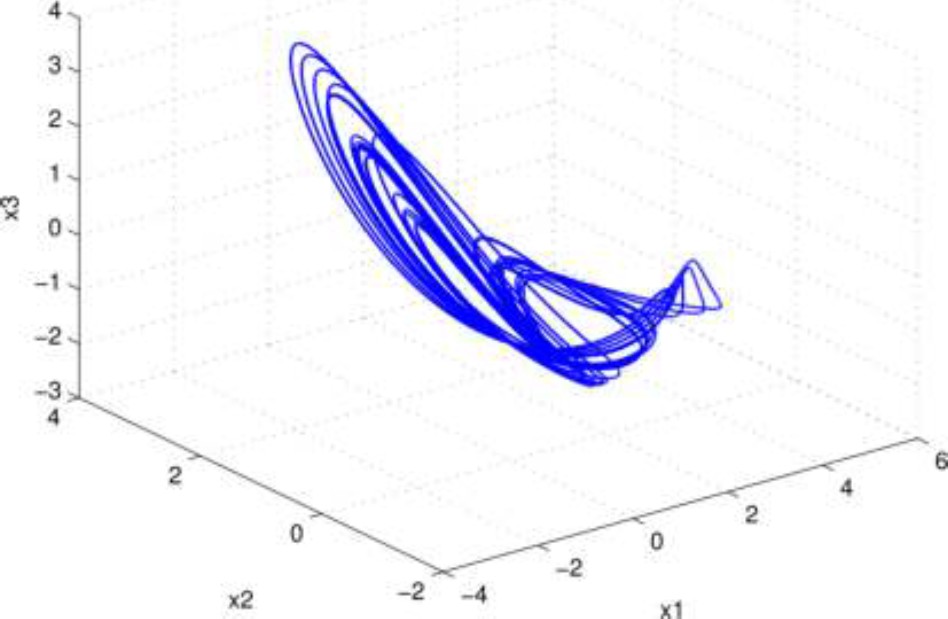

In order to illustrate the behavior of the variable-order fractional hyperjerk system (14)-(17), Fig. 2, shows the phase-space considering three states variables

Fig. 2 The 3D phase portrait of variable-order fractional hyperjerk system into

Whereas, Fig. 3 depicts the function used as fractional variable-order. It is defined as in (19):

We can observe that the order

4 Synchronization Scheme

According to [1] the analysis of synchronization phenomenon in the evolution of dynamical systems has been a subject of active investigation since the earlier days of physics.

It started in the 17th century with the finding of Huygens that two very weakly coupled pendulum clocks (hanging at the same beam) become synchronized in phase.

Synchronization of chaos refers to a process wherein two (or many) chaotic systems (either equivalent or nonequivalent) adjust a given property of their motion to a common behavior due to a coupling or to a forcing.

The purpose of this section is to present a scheme about the controller

The active control approach is considered as an alternative to achieve the complete synchronization between a pair of variable-order fractional hyperjerk systems with different dynamics and also different initial conditions.

First, we consider

We define the drive system as in (20)-(23) and response system as in (24)-(27) as follows:

And:

According to [18], the dynamical systems achieve synchronization if the following equation:

With

where the unknown terms

Equation (29)-(32) together with (20)-(23) and (13) yield the dynamic of the error system:

We define the active control functions,

The terms

Hence:

According to (41) and (42)-(45), it is clear that the system is asymptotically stable. On the other hand, synchronization can be corroborated by means of the phase portrait, which will produce a 45° line when the variables involved reach synchrony.

Fig. 7 presents the phase portraits between

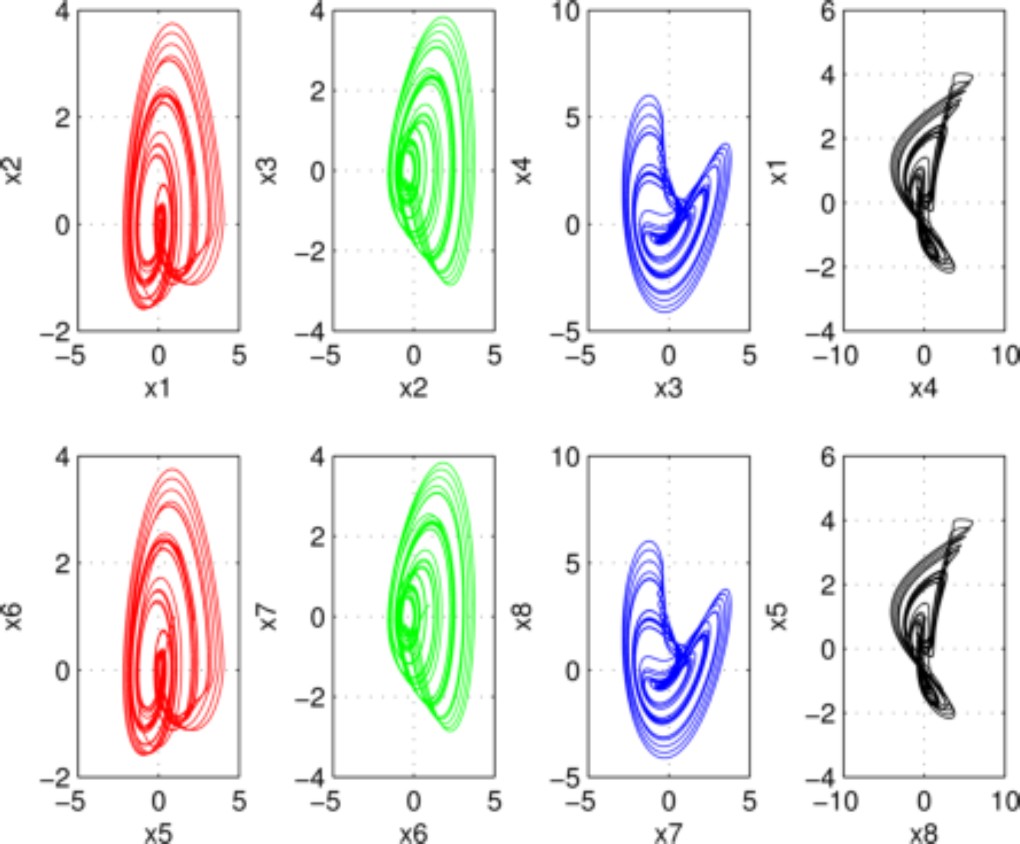

Fig. 4 Phase planes. In top row the phase-portraits corresponding to drive system (20)-(23); in bottom row the phase-portraits corresponding to response system (24)-(27), respectively

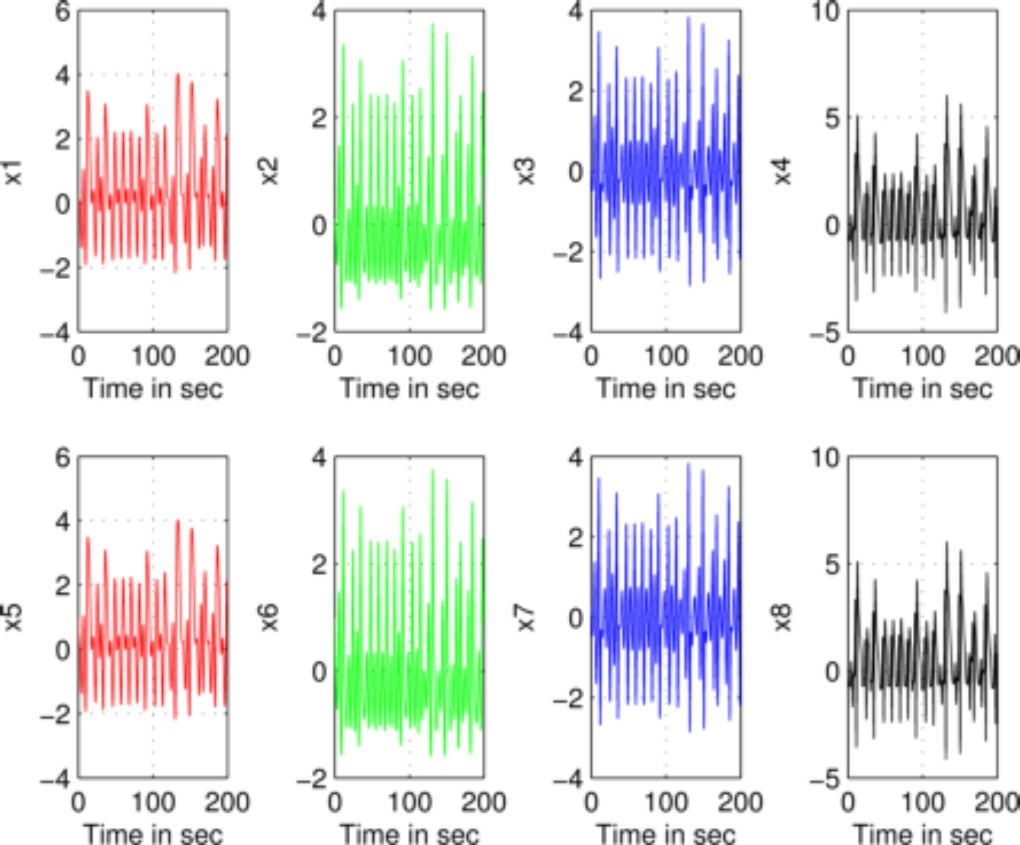

Fig. 5. in the time of the state trajectories

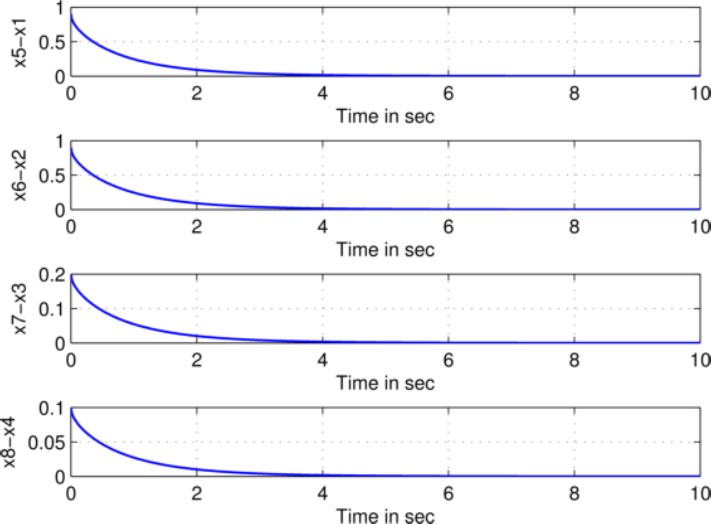

Fig. 6 Error synchronization curves of (20)-(23) and (24)-(27) systems both with a variable-order fractional

5 Results

In this section, the numerical results are given to verify the correctness of theoretical results in the above sections.

The variable-order fractional Grünwald-Letnikov algorithm is used to compute the solutions of the variable-order fractional systems (20)-(23), and (24)-(27) with a time-step

The parameters are defined as

The initial error is

From Fig. 5, it can be seen that the proposed control

The graphical presentation of the synchronization through error analysis is depicted in Fig. 6, we can see that we got the required synchronization via active control method.

In Fig. 7, we present the synchronization in the phase space for each state-variables

6 Conclusion and Future Work

Variable-order fractional calculus has been extended from the notion of constant-order fractional calculus with the order of differentiation or integration varying with time

It has been highly neglected since it was proposed. Nevertheless, researchers have found a large variety of applications that can be modeled and more clearly understood in the applied mathematics área.

A variable-order chaotic system was realized using the proposed fractional order derivative with the consideration that their fractional orders change dynamically in time (for a hyperjerk system).

Also, the master-slave synchronization between two variable-order fractional chaotic systems was presented. The synchronization scheme was achieved based on active control theory.

As we can see in our mathematical analysis, and also in Fig. 6 and Fig. 7, we observe that the system is asymptotically stable.

This topic is very extensive and new, so we can mention that for possible future work it can be considered this topic to apply it in data encryption, even with another control technique.

Finally, we hope our work about variable-order fractional calculus would generate interest from related scholars in the future and also hope that their work may result in significant contributions to this field.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)