Introduction

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) (family Coronaviridae, genus alphacoronavirus) has an enveloped, single stranded, positive sense RNA genome that is ≈28 kb in length (Stevenson et al., 2013). This virus was first documented in the United Kingdom in 1971 as a swine disease resembling transmissible gastroenteritis (Vlasova et al., 2014). In swine in the United States, PEDV is characterized by watery diarrhea, anorexia, variable vomiting and high mortality, particularly in neonates (Chen et al., 2014). The most severe signs are reported in piglets under two weeks old, in which diarrhea causes severe dehydration and is associated with mortality rates as high as 100% in affected litters; however, the health of pigs of all ages is affected (Carvajal et al., 2015).

PEDV preferentially replicates in the enterocytes that line the villi of the small intestine, though crypt cells have also been shown to support viral replication to some degree in both the small intestine and colon (Kim & Chae, 2000). During the infection, pigs exhibit severe villous atrophy with the gradual lengthening of crypt cells due to regeneration of enterocytes. The markedly reduced villus:crypt length ratio, which ranges from 3:1 to 1:1, leads to malabsorption (Song & Park, 2012; Madson et al., 2014). In neonates, the development of villus atrophy via in vitro enterocyte apoptosis has been reported as early as 6 h post infection and to increase with the duration of the infection, resulting in 87.4% of cells becoming apoptotic at 48 h post infection. In contrast, apoptosis was first observed in vivo 3 days post infection (Kim & Lee, 2014). The slower turnover of enterocytes in neonatal (5-7 days) compared to three week old piglets (23 days) may explain, at least in part, the higher susceptibility of younger piglets to PEDV (Carvajal et al., 2015). The ultrastructural changes and mild vacuolation observed in infected colonic epithelial cells may interfere with crucial water and electrolyte reabsorption; dehydration is exacerbated by vomiting, but the mechanisms by which vomiting is induced in PEDV infection are not yet well understood (Madson et al., 2014; Jung & Saif, 2015).

PEDV cannot be diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings alone, and acute outbreaks of this virus cannot be clinically differentiated from transmissible gastroenteritis (TGEV) regardless of the age of pigs infected; laboratory methods are necessary for an etiologic diagnosis (Pospischil et al., 2002). At present, there are studies in animals that have novel methods for the diagnosis and detection of subclinical diseases, inflammation, infection, neoplasia, stress and trauma; all these events are responsible for inducing an acute phase response or (APR) (Cray, 2012). The APR is the body’s way of reacting to the presence of tissue damage or infection, it consists of a series of physiological responses that seek to repair the damage, recruit the host’s defense mechanism to fight the threat and, eventually, restore internal equilibrium (Piñeiro et al., 2007a). The APR is induced by protein hormones called pro inflammatory cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α) that are secreted primarily by monocytes activated in presence of bacterial toxins, or in response to local tissue injury, they then diffuse into the bloodstream where they can be detected in “pulses” (Murtaugh et al., 1996).

These pro inflammatory cytokines act on hepatocytes to induce the acute phase proteins (APP) synthesis, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) (Gabay & Kushner, 1999), serum amyloid A (SAA), pig major acute-phase protein (PIGMAP), and haptoglobin (HAP) (Llamas-Moya et al., 2008). Consequently, some APP (CRP and SAA) in pigs may be affected by age related changes (Llamas-Moya et al., 2007); APP can be classified according to the magnitude of their increased or decreased serum concentrations (positive APP, such as HAP, SAA and CRP vs. negative APP, such as albumin) during an APR (Petersen et al., 2004). For over a decade, blood plasma/serum APP have been widely used to investigate human and domestic animal diseases (Murata et al., 2004), since they are known to be sensitive markers of health and disease processes in pigs (Sánchez-Cordón et al., 2007; Eckersall & Bell, 2010; Kakuschke et al., 2010). Recently, more studies on immunological markers linked to IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and APP in viral processes that affect the swine industry have been included: porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) (Gómez-Laguna et al., 2011; Schweer, 2015), TGEV, PEDV, and porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV) (Salamano et al., 2008; Cray et al., 2009; Wallgren et al., 2009; Langel et al., 2016; Singh, 2016).

However, the interaction involved in modulating the concentrations of different APP in the presence of pathogenic agents seems to be subject to virus specificity; for example, PEDV has been shown to be absent in some organs, since lung tissue from oronasally infected pigs was negative for the PEDV antigen, indicating that PEDV replication did not occur in the lower respiratory tract (see Stevenson et al., 2013). For this reason, the objective of this study was to determine the relationships between four APP (CRP, SAA, PIGMAP, HAP) and the pathological effects of PEDV in suckling piglets and lactating sows at the onset of infection.

Materials and methods

Animals and groups

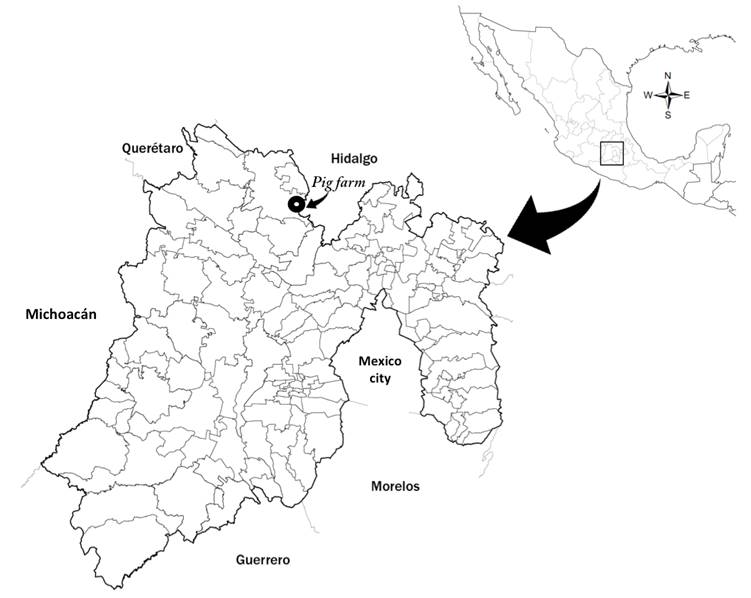

A total of 15 neonatal piglets (born to Yorkshire-Landrace sows at a university swine farm, Research Center, CEIEPP/UNAM; located in Jilotepec in central Mexico) were sampled (Figure 1). The outbreak began on March 22, 2014. With an average of 171.5 sows in production per month (reproductive performance: 2.45 parity rate per sow), this university farm performs two functions: first, it sells pigs in different productive ages, including weaned piglets, finalized hogs, gilts, semen and meat by products; and, second, it is a training and research center for professors and students.

Figure 1: Geographical location of the university farm (coordinates: 19.9544488,-99.515779) where the PEDV outbreak occurred, Jilotepec locality in the State of Mexico. In 2013, PEDV emerged in the states of greater porcine production: Michoacán, Jalisco, Querétaro and Guanajuato; one year later, this disease was spread to other states surrounding Mexico City: State of Mexico, Puebla, Tlaxcala. Finally, the pathogen affected pigs from different farms in the north of the country (such as Sonora and Sinaloa).

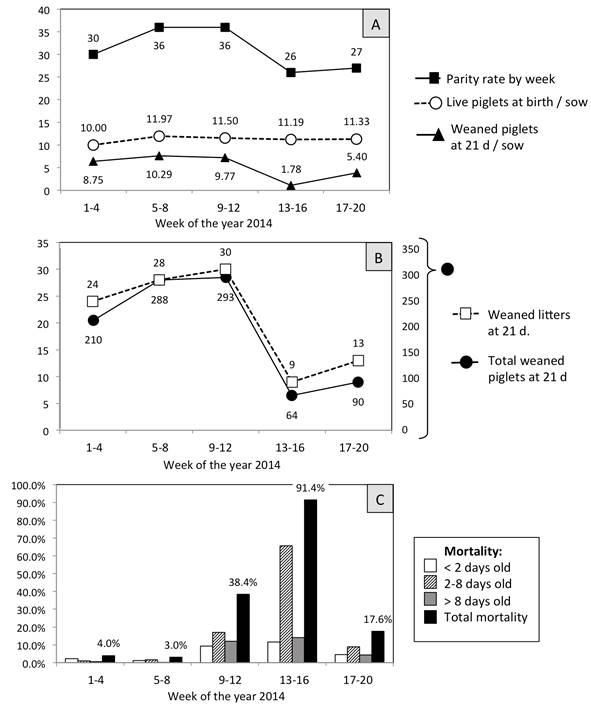

Median monthly production of liveborn and weaned piglets on this farm is approximately 390 and 346, respectively (Figure 2-A). However, during the epidemic outbreak, the piglets were that mainly affected at the beginning of April 2014; the principle signs manifested by the piglets at this center were diarrhea, vomiting and dehydration, with the latter being the main cause of mortality. The deaths of these animals reduced the number of both weaned piglets and litters at 21 days (Figure 2-B). The pre weaning mortality rate was determined to be 4% in January (weeks 1-4) and 3% in February (weeks 5-8), but increased in the months of March (weeks 9-12) and April (weeks 13-16) to 38.4% and then 91.4% (Figure 2-C).

Figure 2: (A) The average number of births was 36 (171.5 sows) up to weeks 9-12 of 2014, but after weeks 13-16 this index decreased, though the number of liveborn piglets was maintained (11.97, 11.05, 11.19). However, (B) the number of weaned piglets (293 to 64) and weaned litters (30 to 9) both descended at 21 days. Although the piglets continued to consume milk, weight loss, dehydration, vomiting and diarrhea were characteristic signs that preceded death. (C) The mortality rate among the piglets on the farm increased from 3% in weeks 5-8 to 38.4% and 91.4% in the following 8 weeks. The life expectancy of the sick piglets was the third day of life. The high pre weaning mortality rate is a characteristic sign for diagnosing some viral diseases, including PEDV.

Pathological diagnoses by necropsy were performed on the dead piglets to identify the PEDV. Findings included: reduced muscle mass, dehydration, generalized jaundice, ileitis and enteritis. An additional observation was thinning of the intestinal walls (especially of the small intestine, which had an almost transparent appearance). The stomachs of some piglets contained evidence of undigested milk, suggesting that they did not lose their appetite during the epidemic. Complementary laboratory diagnoses were conducted at the Virology Laboratory of the Microbiology and Immunology Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Zootechnology, at the UNAM, using the polymerase chain reaction technique (PCR) with samples of feces, diarrhea and fresh intestine (jejunum, ileum and colon).

Also, in accordance with the study objectives, the piglets that survived the first day were sampled. Blood and serum samples were collected and grouped according to the animal’s health status, as follows: one day old piglets without enteric signs (ES or Control group), and one day old piglets with ES such as diarrhea and vomiting (DVP group). Similarly, blood and serum samples were drawn from a total of 12 sows according to their health status: lactating sows without ES (Control group, n=6), and lactating sows with ES such as diarrhea and vomiting (DVS group, n=6) (Table I).

Table I: Groups of piglets sampled according to their health status: one day old piglets without enteric signs (ES or Control), and one day old piglets with ES such as diarrhea and vomiting (DVP). Also, groups of sows sampled according to their health status: lactating sows without ES (Control) and lactating sows with ES such as diarrhea and vomiting (DVS).

| Group | Identification | n | Health status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piglets (1 day old) | Control | 7 | No enteric signs |

| DVP | 8 | Diarrhea and vomiting | |

| Sows | Control | 6 | No enteric signs |

| DVS | 6 | Diarrhea and vomiting |

Blood sampling and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis

All piglets were sampled by vena cava puncture, while the sows were sampled by jugular puncture. Each animal was held and samples were drawn under minimum stress conditions following the norm NOM-062-ZOO-1999. Five milliliter blood samples were collected in tubes containing anticoagulant using 10 mL-1 syringes and 22-mm needles for the piglets, and 40 mm needles for the sows. This project was previously approved by a Bioethics Committee (IACUC) at the UNAM.

All samples were centrifuged at 3,500 g for 10 min, and the plasma was stored at -20°C. The identification and quantification of APP was performed according to the manufacturer's specifications. Serum free HAP was quantified spectrophotometrically according to its peroxidase activity using a commercial ELISA kit (Tridelta Development Ltd., Maynooth, Ireland).

The concentration of SAA was determined using a non species specific commercial ELISA kit (PhaseTM Range; Tridelta Development Ltd.). CRP and PIGMAP levels were quantified by monoclonal antibody sandwich ELISA assays (PhaseTM Range; Tridelta Development Ltd.; PigCHAMP Pro Europa S.A., Segovia, Spain). All samples were analyzed in duplicate after pre dilution to 1:35,000 for HAP, 1:500 for SAA, 1:1000 for CRP, and 1:1000 for PIGMAP.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation of the results was performed using a commercially available statistical software package: R 3.3.1 Core Team (2016). R: A language and environment for Statistical Computing. R. Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, To Windows 10.

PIGLETS and SOWS: A non parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. When between group differences were found, a Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test was applied. For both tests, values were evaluated with an alpha of 0.05

RESULTS

PIGLETS

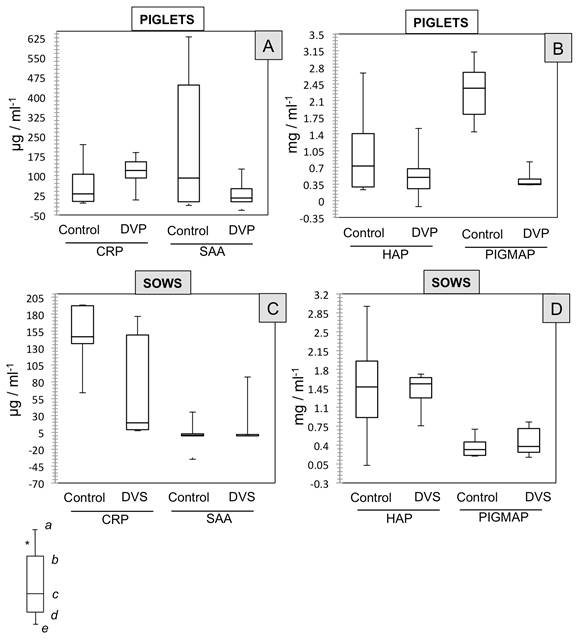

No significant differences were found in the data (medians) for CRP concentrations in the piglets in the control (30.4650 μg/mL-1) and DVP groups (119.20 μg/mL-1). Similarly, no such differences (P>0.05) were observed between the groups for the other proteins measured (Figure 3-A and 3-B): SAA (Control: 84.52 μg/mL-1 vs. DVP: -12.45 μg/mL-1), HAP (Control: 0.7269 mg/mL-1 vs. DVP: 0.4948 mg/mL-1), and PIGMAP (Control: 2.365 mg/mL-1 vs. DVP: 0.3541mg/mL-1).

Figure 3: Effect of PEDV on the concentrations of four different APP (CRP, SAA, HAP, PIGMAP) shown by medians (non-parametric data) in four groups of piglets and sows classified according to their health status. PIGLETS [A and B]= Control: one-day-old piglets without signs of disease; DVP: one day old piglets with enteric signs (ES) such as diarrhea and vomiting. SOWS [C and D]= Control: sows without ES; DVS: sows with ES such as diarrhea and vomiting. Symbols (a, b, c) indicate significant differences with α<0.05. *Each box shows: (a) upper extreme concentration; (b) upper quartile 25%; (c) median 50% data; (d) lower quartile 25%; and, (e) lower extreme concentration.

SOWS

In the case of the sows, results were similar, as no significant differences were found (P>0.05) between the Control and DVS groups for the 4 different concentrations (medians) of the proteins measured (Figure 3-C and 3-D): CRP (Control: 146.78 μg/mL-1 vs. DVS: 19.06μg/mL-1), SAA (Control: -31.85 μg/mL-1 vs. DVS: 0.00 μg/mL-1), HAP (Control: 1.4758 mg/mL-1 vs. DVS: 1-5365 mg/mL-1), and PIGMAP (Control: 0.3166 mg/mL-1 vs. DVS: 0.375 mg/mL-1).

Discussion

Previous studies have determined the serum biological ranges of several APP in healthy pigs (CRP, HAP, SAA, PIG-MAP) in different stages of commercial production, from birth on the farm until sacrifice in an abattoir (Pomorska et al., 2012). In this regard, Pomorska and cols., point out that the increase in the concentrations of these four proteins is affected by age; for example, the concentration of CRP ranged from 18.83 ±12.36 μg/mL-1 in 7 day old piglets to over 28 μg/mL-1 in 13 week old animals (P<0.05), before remaining at that level to the end of the study. Later, the increase in HAP serum concentration was from 0.63±0.16 mg/mL-1 in the first week of life to over 1 mg/mL-1 in older pigs (from 10 weeks of age). The levels of HAP observed after 10 weeks of life were significantly higher than those of pigs before weaning (P<0.05). Also, during the first 4 weeks of life, median SAA levels remained relatively stable, ranging from 0.92 to 1.16 μg/mL-1 (P≥0.05). Significant differences were found between serum SAA concentrations up to 4 weeks of life and those observed in 16 week old animals (P<0.01). Finally, the median concentration of PIGMAP ranged from 0.84±0.1 mg/mL-1 to 1.30±0.24 mg/mL-1 during the study period. Beginning at 13 weeks of life, the median concentrations of PIGMAP were significantly higher (P<0.05) than the levels observed in animals younger than 8 weeks.

The absence of statistical differences between sick pigs and those of the control group suggests that there was no direct stimulus on the synthesis of APP. It is likely that the immune response of pigs is not affected by the virulence of PEDV in such a short time, that it is insufficient to activate an axis or signal for pro inflammatory proteins. By other hand, APP concentrations have been shown to increase due to inflammation resulting from tissue damage or infection (Parra et al., 2006), though high levels of APP have also been observed after physical or psychological stress (Murata et al., 2004). Indeed, in recent years APP have been used as biological indicators of prolonged stress processes; for example, levels of the CRP and HAP proteins were seen to increase after 48 h of transport by truck. Also, PIGMAP was found to increase after episodes of tail biting and after 24 h of transport by truck in both adequate and poor conditions. Finally, CRP, HAP and PIGMAP levels have been seen to increase after repeated bleeding protocols (Piñeiro et al., 2007b; Salamano et al., 2008).

In other cases, serum CRP levels increased during experimental infection with the respiratory pathogen Actinobacillus p. (Skovgaard et al., 2009); where as HAP levels were increased by coronavirus infection (Grau-Roma et al., 2009). CRP and HAP are also valuable markers of natural infections by various porcine viruses and Mycoplasma (Parra et al., 2006). Tam et al., (2007) evaluated circulating CRP in piglets (3.5 ± 2.3 days old) following exposure to acute intermittent hypercapnic hypoxia for 6 min. They observed that CRP did not differ significantly between the control and treatment groups. Thus, these authors suggested that while the exact role of APP in viral infections remains unclear, their induction might represent a non specific hepatic response to circulating cytokines.

For other viral agents, such as swine influenza virus (Belgium/1/98 (H1N1), which was isolated from the lungs of fattening pigs during an outbreak of acute respiratory disease, CRP and HAP were seen to peak later in the infection than the cytokines. Additionally, serum concentrations increased to a greater degree than those in the fluid from bronchoalveolar lavage in 3 week old pigs (Barbé et al., 2011). Infections with A. pleuropneumoniae were found to induce an immediate, but brief, IL-6 response, followed by SAA responses. This evidence indicates that APP expression occurs in different cell types, such as peripheral lymphoid tissues, leukocytes, tonsils, spleen cells, and tracheobronchial lymph nodes, and that the systemic APR arises within 14-18 h after experimental lung infection (Hultén et al., 2003).

Conversely, recent reports have ruled out the possibility of diagnosing and isolating PEDV in several organs. For example, lung tissues from oronasally infected pigs were negative for the PEDV antigen, so no evidence of PEDV replication was found in the lower respiratory tract (Stevenson et al., 2013; Jung et al., 2014). In addition, no PEDV antigens were detected in other major organs, such as the pylorus, tonsils, spleen, liver and kidneys. Another recent study, however, revealed replication of PEDV in porcine pulmonary macrophages, both in vitro and in vivo (Park & Shin, 2014). Thus, the question of whether extra intestinal replication of PEDV occurs remains unresolved.

Other viruses, such as PRRSV, TGEV, and influenza H1N1, may increase both pro inflammatory cytokines (eg. TNF-α) and APP (eg. CRP and HAP) at 7 and 14 days post infection (Che et al., 2012; Singh, 2016). Therefore, the question of whether or not PEDV causes an inflammatory process and activates cytokines capable of triggering the APR by inducing hepatocytes remains unclear (Gabay & Kushner, 1999; Hoang et al., 2013).

There is only limited information in scientific reports that have related the pathological effects of PEDV to serum increases of acute phase proteins in pigs, though several studies have been published on viral and bacterial respiratory cases (Cray et al., 2009).

Conclusions

The role of PEDV in different inflammatory processes remains unclear, and few studies have addressed this topic. Until now, the proteins observed and quantified in this study were not the specific immunological markers and adequate for the early diagnosis of the PEDV in piglets or sows, due perhaps to the limited hepatocyte production to elevate the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

It is important to note, however, that increases in APP have been widely described in response to viral and bacterial agents that present mainly acute respiratory clinical signs, as well as in prolonged situations of stress, such as fasting or the transport of pigs to slaughter. Thus, the evidence presented by other authors suggests that the synthesis and increase of APP in the bloodstream is strongly related to the degree of affectation or loss of homeostasis. We believe that the synthesis of acute phase proteins is modulated by the lack, or total absence, of basic biological requirements and their order of physiological importance; that is, (1) breathing (eg. hypoxia and pneumonia); (2) physical damage (eg. being struck, experiencing pain, and bleeding); (3) hunger (eg. fasting and dehydration); (4) welfare (eg. overcrowded housing and chronic stress); and, (5) disease (i.e., the degree of virulence).

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)