1. Introduction

Mitochondria are cell organelles where different metabolic pathways take place. The best recognized is oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), the process to produce ATP. Other pathways, such as beta-oxidation, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), some amino acid metabolism, and heme group synthesis are also carried out in the mitochondria. Therefore, mitochondria work as metabolic regulators.1

The respiratory chain is a four-enzyme complex (I-IV) system that produces an electrochemical gradient used for ATP synthesis by ATP synthase (complex V). The whole process integrates OXPHOS and is located at mitochondrial cristae. Any OXPHOS failure promotes a minor ATP availability, energy unbalance and disease expression.

Mitochondriopathies are systemic diseases with many diagnostic issues.2,3 Mitochondria have their own DNA (mtDNA), which genes codify for proteins that are finally integrated into the OXPHOS system. The rest of mitochondrial proteins are imported from the nucleus. Almost all OXPHOS defects manifest as catalytic or assembly failures.

These complexes can also associate with themselves to build supercomplexes or respirosomes,4 which grant bioenergetics efficiency and may be associated with mitochondriopathies key features.5 Disease recognition or diagnosis is difficult because of these aspects. In addition, only OXPHOS issues are included in the search for these diseases, furthermore, mitochondriopathies are systemic diseases that affect different cellular processes. A good treatment scheme is difficult to follow,3 mainly because how these problems influence other pathways or systems is unknown. Therefore, it is important to define the landscape to better care and understanding of the disease.

Proteomics is a strategy to describe simultaneous process in the cell6 and find better therapy options. Considering that five enzymatic complexes, which can be associated to form supercomplexes, integrate the OXPHOS system, a better stratification of these diseases is also possible. This investigation focused on the search for molecular mechanisms underlying mitochondriopathies using skin fibroblasts with a complex IV mitochondriopathy. The results showed that the mitochondrial proteome suffered protein deregulation on OXPHOS system and other mitochondrial paths.

2. Methods

2.1. Cell growth

Primary skin fibroblasts cultures with and without complex IV disease were grown in DMEM/F12 (1:1), 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, CA) and antibiotic/antimycotic (5% CO, 37 ◦C). Mitochondria were isolated from fibroblasts (50 x 106) by differential centrifugation. Cells were disrupted in 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 at 4 ◦C and centrifuged for 10 min at 1500 g and 4 ◦C to recover the supernatant. This step was repeated for three times. Subsequently, all supernatants were pooled and centrifuged for 10 min at 12 000 g and 4 ◦C to obtain a mitochondrial pellet.

2.2. ATP synthesis

ATP synthesis was determined by a coupled enzymatic assay. Briefly, mitochondria were resuspended in 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM glucose, 20 mM Pi, 0.5 mM NADP+, 200 mM ADP, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 μM AP5A, and 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, followed by the addition of 0.2 mg/ml hexokinase and glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase (6 U/ml). Absorbance at 340 nm was measured using an Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer. Each determination was performed twice.

2.3. Western blot

Mitochondrial protein extraction was carried out using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA pH 7.4) to analyze the respiratory complex content. After centrifugation at 10,000 g, 20 μg of protein were loaded in a 12% SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF, 1 h, 100 V, 4 ◦C) with a Towbin buffer (10% Tris, 10% methanol, pH 7). Transferred membranes were incubated with antibodies against different subunits of each respiratory complex and ATP synthase (complex V) (Abcam-MitoSciences®). With the corresponding secondary antibodies (Thermo Scientific Pierce) and Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent kit (Merck Millipore) reaction bands were visualized; the image processing was done with a C-DiGitTM system (Li-COR).

2.4. Proteomics

Isolated mitochondria were resuspended into 100 μl of lysis medium (4% SDS, 100 mM DTT, 100 mM Tris, pH 8.6) supplemented with a protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific) and sonicated ten times (2 s ON and 5 s OFF pulses). Sonicated samples were incubated 30 min at 40 ◦C and alkylated (200 mM iodoacetamide) in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. Proteins were precipitated overnight with ethanol (10:1 V/V) at -20 ◦C, pelleted (10 min, 10 000 g), and dissolved into 50 mM guanidine-HCl, 20 mM Tris. Finally, proteins were digested with Mass Spectrometry Grade Trypsin (1:50, Promega) overnight at 37 ◦C. The resulting peptides were desalted (Sep-Pak C18, Waters), dried and kept at -80 ◦C until protein analysis.

In order to analyze resultant peptides by mass spectrometry, digested proteins were dissolved in 0.1% formic acid (50 μl) and injected (5 μl) three times into a nano-HPLC Ultimate 3000 with an Acclaim PepMap100 C18 column (50 cm). An acetonitrile gradient (5-90%) was performed for peptide elution. HPLC system was coupled to the mass spectrometer ESI-Ion Trap, Amazon speed (Bruker Daltonics), operating in positive 400-1400 m/z. The 20 most abundant ions were fragmented every 50 ms; single charged ions were excluded. An ion database was constructed by the Data Analysis software (Bruker Daltonics) and used for subsequent protein identification with the Mascot search engine.

2.5. Bioinformatics

The South Mississippi University website tools (http://genevenn.sourceforge.net/) were used for protein identification and analysis. Mitochondrial proteins were curated with MitoMiner database (IMPI version Q2, 2016).7,8 Functional protein groups were proposed based on UniProt database (http://www.uniprot.org/) and PANTHER software (http://pantherdb.org).

3. Results

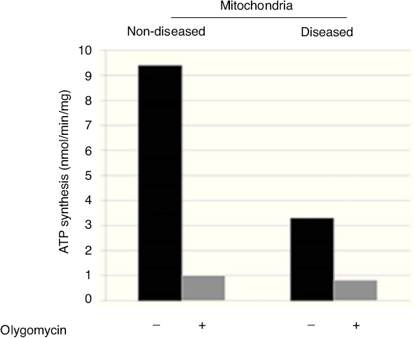

Disease phenotype might be different in cells or not detectable due to mtDNA or mitochondrial quantity in skin fibroblasts. Therefore, the molecular cause of the disease was determined by catalytic assays on muscle tissue.9,10 To determine the disease phenotype, skin fibroblasts were grown to confluence, as explained before, and ATP synthesis was measured trough a coupled enzymatic assay.9,11 Diseased mitochondria presented a ≥ 60% decrease in ATP synthesis as compared with non-diseased mitochondria (Figure 1). This result corroborates that skin fibroblasts kept the disease phenotype reported as affected in the muscular tissue, a complex IV mitochondriopathy.

Figure 1 ATP-synthesis in skin fibroblasts isolated mitochondria showed a decrease of ≥ 60%, which corroborates the mitochondriopathy.

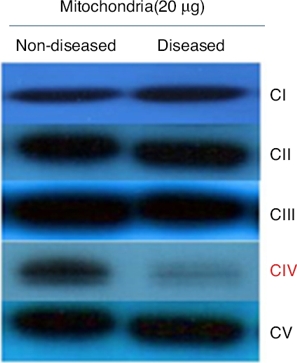

To determine if the diminished activity and ATP synthesis correlated with a complex IV decrease, a Western blot assay was performed testing antibodies against one subunit of each respiratory complex and ATP synthase. These data showed that all complexes were present at normal levels but for complex IV, which was clearly diminished (Figure 2). Thus, it was possible to consider that these fibroblasts presented a complex IV mitochondriopathy. One of the main problems of this desease is due to assembly issues, which affects OXPHOS supercomplex assembly, as in patients with a damaged complex IV where different subassemblies are formed.12,13

Figure 2 Representative Western blot of OXPHOS complexes (I-V). Proteins were isolated from mitochondria and separated by SDS-PAGE. The reaction bands showed a clear decrease in complex IV levels.

Since OXPHOS is a central process in mitochondria,1,3,14 other metabolic pathways are expected to be affected as well. Diseased and non-diseased mitochondria were isolated to extract their proteome and analyze it by mass spectrometry (ESI-Ion Trap, Bruker Daltonics) to determine how these complex IV deficiencies are affecting these pathways. Proteins were identified for non-diseased (795) and diseased (483) mitochondria. Both extractions were conducted simultaneously under the same conditions then the difference between the identified proteins problems could reflect due to the disease.

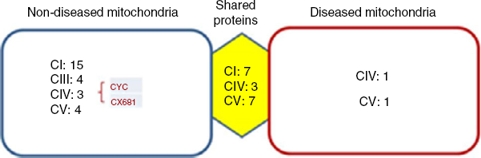

Identified proteins were classified into three groups: proteins present in cells without mitochondriopathy, proteins identified in cells with mitochondriopathy and proteins present in both groups (Figure 3). The largest group of proteins was found in mitochondria without mitochondriopathy. Since those proteins are not present in the other groups, they might be considered as deregulated proteins in cells with mitochondriopathy.

Figure 3 Identified proteins were distributed into three groups. Most proteins present were from OXPHOS. The most affected complexes were those that form supercomplexes (I-III-IV), from which the most affected was complex I. Proteins such as cytochrome c (CYC) might also be deregulated. Complex IV proteins that were identified in diseased mitochondria might be assembly assistants.

Results were crossed with MitoMiner database (IMPI version Q2, 2016),7,8 where 1408 validated proteins are listed, to focus just on mitochondrial processes. Finally, 177 proteins from the group of mitochondria without disease, 34 from the group with diseased mitochondria, and 147 from the group which shared proteins were chosen. In all three groups, the most represented proteins were from the OXPHOS system (Figure 3). The largest number of proteins was found in mitochondria without disease (28), followed by shared proteins (18) and finally diseased mitochondria (4) groups. Among these proteins, some assembly proteins not present in the final complex structure (e.g. complex IV, COA3) were also considered.

Interestingly, the main affected OXPHOS complexes were complex I and III. Skin fibroblasts presented a complex IV problem, which was present in a few proteins maybe because of its membrane character. However, seven sub-units were identified: three for the shared proteins group, three for the non-diseased mitochondria group and one for the diseased mitochondria group, including the complex IV assembly factor COA3.

Another deregulated protein was cytochrome c (CYC). CYC is an electron carrier between III and IV complexes. It was present only in the mitochondria without disease group, signaling a probable deregulation.

The rest of the proteins that were identified are involved in other mitochondrial pathways or metabolic process. They were divided into eight different classes (Figure 4). These are probably the most affected process during this mitochondriopathy.

4. Discussion

In this work, skin fibroblast cells diseased with a complex IV mitochondriopathy were studied. Human complex IV is built from 13 different subunits, any of which could carry mutations and rise a mitochondriopathy.15,16 There are auxiliary proteins that work through assembly processes that can also undergo mutations and may be the origin of the disease.17 The search for mutations in every subunit of this complex is uncertain because many silent mutations without any relationship with the disease may be present. Also, mitochondria are more susceptible to mutations.

Mitochondrial proteome analysis is another approach for this kind of diseases.6 As mentioned before, mitochondriopathies are OXPHOS defects that impact on ATP production. Thus, differences among proteins of these systems are expected. OXPHOS system is formed by membrane proteins and is very dynamic in producing supercomplexes that grant bioenergetic integrity. Although their role is not completely understood, it is known that they are involved in different aspects of mitochondriopathies and cardiac diseases.18-20 (19) From these results, it is proposed that the proteins in the mitochondria without disease group could be deregulated proteins since, under similar conditions, they are not present in the other groups. The shared proteins could indicate less dramatic changes because they are present in both groups. Finally, it is possible to think that there are compensatory or accumulated proteins in the diseased mitochondria group because of the pathological molecular changes. In all cases, the vast majority were OXPHOS proteins. Main changes were observed in mitochondria without the disease. Accordingly, the most affected proteins were from complex I, followed by complex III and IV, and finally complex V (Figure 3). These complexes are those with more interactions in supercomplexes and include protein subunits codified by mtDNA. It is highly probable that a mitochondrial defect as the one reviewed in this paper can change the supercomplex dynamics and function.21,22

In this type of mitochondriopathies, in vitro evidence has shown that complex IV defects rise partial supercomplexes with deficient or unstable complex I assembly.5 On the other hand, patients who carry complex IV defects could present different subassemblies17 that limit or diminish the supercomplex formation. One of the best-understood super-complex function is substrate channeling. Our data showed that CYC is deregulated. This protein works as an electron carrier between complex III and IV, so its presence in the mitochondrial proteins without disease could indicate channeling problems because of the supercomplex absence. This last fact is strengthened if it is considered that the complex IV subunit COX6B1 is also deregulated. Complex IV works as a dimer and COX6B1 is a linking subunit at the dimeric interface; also, mutations in this subunit are present in mitochondriopathies.23,24 Due to COX6B profile, it is easy to suppose that defects present on this mitochondriopathy are regarding assembly issues, which is supported by a diminished catalytic activity (Figure 1) and decreased levels (Figure 2) of complex IV. In this sense, it is interesting to notice that complex IV proteins identified in the diseased mitochondrial group participate in assembly assisting or are added at the end of complex IV assembly process.

Moreover, complex V proteins are also affected. This complex performs ATP synthesis and can form super-complexes with itself to initiate mitochondrial cristae biogenesis. Therefore, this cell model might have mitochondria with an altered ultrastructure. Finally, it is interesting that complex II subunits are present only in the groups of shared proteins and in diseased mitochondria, probably as a compensation effect due to complex I deregulation. Complex II is an additional gate to respiratory chain and OXPHOS; hence, its accumulation or supposed increase may reflect an overexpression as an attempt to supply bioenergetic cell demands.

Considering that ATP production is one of the principal processes in the cell, and represents the main energy source, mitochondria can be treated as a metabolic regulator. Therefore, complex IV defect described can also reach other mitochondrial routes. To further investigate on this, identified proteins were regrouped into eight functional classes (Figure 4). These classes showed differences in comparison to the previous groups (mitochondria without disease, shared proteins and diseased mitochondria). Although all presented mainly OXPHOS changes, probably because of complex size and subunit number, it was possible to have a glimpse of some other processes. In the group of shared proteins, ‘‘minor’’ changes were found in proteins associated with the cytoskeleton, calcium homeostasis, and detoxification. In the group of non-diseased mitochondria, besides OXPHOS, proteins related to genetic information processes (DNA replication, transcription, and translation), β oxidation and TCA cycle were found affected. Finally, in the group of diseased mitochondria, OXPHOS, some RAS-related and some carrier proteins were observed.

As it has been shown, this kind of proteomic characterization could be useful for mitochondrial disease classification. Experimental corroboration of these results could orient to better care for these patients or therapy design.

In this cell model, CYC is proposed as a good target to compensate substrate channeling or focus on other affected pathways to reduce problems related to complex IV.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)