INTRODUCTION

Fluorescence, the re-emission of absorbed light at a longer wavelength by specialized molecules, is a widespread phenomenon in several metazoan phyla, most commonly studied in Cnidaria, Arthropoda, and Chordata (Macel et al. 2020). It can be encountered in diverse patterns ranging from the red fluorescent tips of the tentacles of siphonophores to the green spots on the backs of salamanders (Haddock et al. 2005, Lamb and Davis 2020). Fluorescence may be produced from extrinsic compounds and fundamental biological building blocks, such as riboflavin, chitin compounds, and amino acids like tryptophan (Lakowicz 2006, Yang et al. 2016). Organisms can produce these molecules intrinsically or obtain them extrinsically from their diet or symbionts.

Recent work has focused on identifying fluorescent proteins and addressing the ecological roles fluorescence patterns may serve, though these claims are debated. In marine invertebrates, empirically supported organismal and ecological functions of fluorescence suggest that it may be used for photoprotection, prey attraction, and intraspecific communication (Mazel et al. 2004, Lim et al. 2007, Haddock and Dunn 2015, Marshall and Johnsen 2017). Despite the wide distribution of fluorescence among some groups, such as Scleractinia and other cnidarians (Matz et al. 1999, Shagin et al. 2004, Alieva et al. 2008, Gruber et al. 2008, Kubota 2010), it is still unclear for most taxa whether these patterns correlate to innate biological factors (e.g., taxonomic relationships and developmental stages) or ecological interactions (Oswald et al. 2007 for corals; Haddock and Dunn 2015 for the hydromedusa Olindias and others). The comprehensive study of fluorescence patterns among undersampled groups to improve understanding could potentially lead to the identification of informative tools to delimit species and assess biodiversity.

Hydrozoans, a widespread and diverse group of cnidarians (Gravili 2016), represent an ideal system for studying species-specific fluorescence patterns. Notably, green fluorescent protein (GFP) was first isolated from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria (Shimomura 2005). Since then, fluorescence from a variety of sources has been documented in other hydrozoan taxa (Pugh and Haddock 2010, Gravili et al. 2012, Maggioni et al. 2020). Despite the history of fluorescence research in hydrozoans, it has yet to be systematically studied within the broad diversity of this animal group, and surprisingly little is known about the distribution and morphological variation of fluorescence in hydrozoans beyond selected genera or species. Fluorescence is thought to be a common feature in hydromedusae, but few species have been studied to identify its presence or distribution (Kubota 2010). Even fewer studies have looked at fluorescence in hydrozoan polyps, and it has been suggested that it is a rather rare trait in hydroids (Kubota et al. 2011).

Within hydrozoans, GFP, a molecule that emits green light when excited, is a common source of fluorescence and has been harnessed as an essential tool in molecular and cell biology research (Chudakov et al. 2010 and references within). Since the discovery of GFP, other proteins from the GFP family have been described and isolated from various taxa (Masuda et al. 2006, Bomati et al. 2009). These proteins are most diverse among anthozoans, particularly non-luminous anemones and scleractinian corals, offering a palette of green, yellow, orange, and red fluorescent hues (Labas et al. 2002, Schnitzler et al. 2008). Other homologous fluorescent molecules, such as yellow fluorescent protein or cyan fluorescent protein, with different emission spectra have also been identified (Matz et al. 1999, Shagin et al. 2004). Different fluorescent compounds have particular excitation spectra that usually exhibit a mirror image of the emission spectra (e.g., Matz et al. 1999). Molecules like GFP, which are maximally excited with blue light, are often also excitable by violet or ultraviolet light, whereas cyan fluorescence requires shorter wavelengths below the wavelength of emission. Incidental autofluorescence is found in nematocysts and other cells. However, while we did conduct some surveys with ultraviolet and violet light sources, our focus in this study was on fluorescence with the potential to be excited by blue environmental light.

Although hydrozoans are abundant and diverse in both benthic and pelagic habitats, this group also presents some challenges. In areas with little taxonomic exploration, such as tropical regions, limited information is available on species richness and biogeographic ranges of hydrozoans. Indeed, only one specific survey has been conducted to assess the diversity of hydrozoans along the Caribbean coast of Panama, and it reported 70 taxa (Miglietta et al. 2018). In the 1970s, Ángeles Alvariño (1974) surveyed the siphonophore diversity in Panama, encompassing the Pacific and Caribbean Seas adjacent to the Panama Canal, and reported 30 species.

In addition, hydrozoans show a relatively high degree of cryptic diversity and morphological variation, which leads to the misinterpretation of diagnostic characteristics and difficulties in determining species boundaries (Cunha et al. 2016, Maggioni et al. 2016, Montenegro et al. 2023). Fluorescence patterns coupled with morphological and molecular data offer a promising diagnostic tool for species identification (Kubota et al. 2008, Kubota 2010, Maggioni et al. 2020). Furthermore, fluorescence can be used to reveal hydrozoan species that may otherwise go unnoticed due to their small size or obscurity while overcoming the challenges associated with species delimitation.

Here, we present a survey of fluorescence patterns across hydrozoans in Bocas del Toro, Panama. This survey includes hydroids, hydromedusae, and siphonophores in pelagic and nearshore areas of the region, complementing the few surveys conducted previously (Alvariño 1974, Miglietta et al. 2018). By expanding our knowledge of the observations and diversity of fluorescence patterns in hydrozoans, this study serves as a scaffold for documenting and understanding the overarching distribution of fluorescence across a diverse marine invertebrate group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling

Medusae and polyps of various species of Hydrozoa were collected at 9 sampling points in the Bocas del Toro Archipelago, Panama (Fig. 1, Supplementary Material Table S1), during the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) taxonomy course “Systematics and Biology of Ctenophora and Medusozoa” from 11-29 July 2022. The medusae were collected by snorkeling and plankton tows using a 0.5-m plankton net (500 µm) across different habitats, including mangroves, seagrass beds, coral reefs, and the offshore open ocean, at depths between 0 to 25 m. Ten plankton tows were conducted during the day, and 2 tows were carried out during the night. Specimens were kept alive in fresh seawater for a maximum of 24 h before further processing and were sorted and analyzed at the Bocas del Toro Research Station of STRI.

Morphological identification

Hydromedusae and polyps were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level using available literature (Kramp 1959, Cornelius 1995, Schuchert 2012, Miglietta et al. 2018, Schuchert and Collins 2021) and additional taxon-specific literature as necessary. Living specimens were analyzed using an Eclipse E200 compound microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) at various magnifications (40-100×), and larger specimens were observed using either an SMZ-1500 stereomicroscope (0.75-11.25×) (Nikon) or a Zoom 2000 stereomicroscope (7-30×) (Leica Camera AG, Wetzlar, Germany).

Fluorescence examination, imaging, and phylogenetic mapping

In total, 74 hydrozoan individuals were examined (Supplementary Material Table S2). All anthomedusae (n = 28), leptomedusae (n = 15), siphonophores (n = 12), hydroids (n = 8), limnomedusae (n = 8), and narcomedusae (n = 3) were checked for fluorescence emission using an Xite Royal Blue (440-460 nm) LED-flashlight (NightSea, Hatfield, USA) and a Yellow #12 long-pass filter (Tiffen, Hauppauge, USA). Informal observations were also made with violet and ultraviolet light sources, but those patterns did not substantially differ and were not collated for this study. Images were taken using a 3.5-90× stereomicroscope (AmScope, Irvine, USA) or a D750 DSLR camera (Nikon) with white light, blue light, and blue light with a yellow filter.

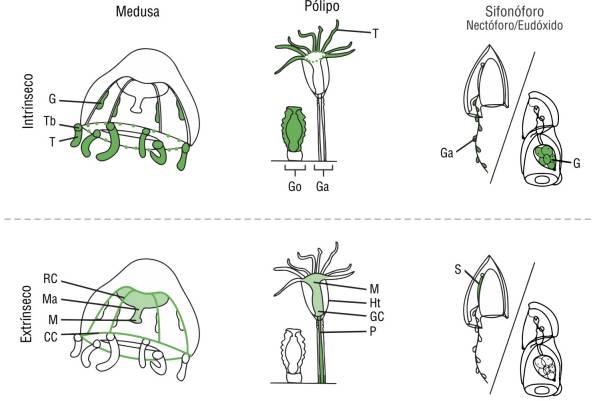

Specimens were examined for 2 characteristics: fluorescence origin and fluorescent morphological structure. Fluorescence origin types were classified as extrinsic, intrinsic, mixed, or none, depending on the potential origin of the fluorescent proteins, which could come from the individual itself or its food source. Extrinsic (diet-derived/prey-associated) fluorescence may be visible within the gastrovascular system of transparent medusae and may have other spectral properties. For example, red fluorescence (600-700 nm) may be derived from the chlorophyll of symbiotic algae (Mazel et al. 2003) or phytoplankton (Yentsch and Phinney 1985). Yellow fluorescence can be emitted from GFP-like homologs, such as yellow fluorescent protein, and from various vitamins, such as riboflavin/Vitamin B (525 nm) (Yang et al. 2016), present in bacteria (Petuskhov et al. 1995). If fluorescence was present in any other morphological structure or body part outside the gastrovascular system, it was deemed intrinsic. Specifically, fluorescence in the radial canals, circular canal, or manubrium was deemed extrinsic, while fluorescence in the gonads, umbrella, oral lips or lopes, mouth and oral arm region, tentacles, tentacle bulbs, or tentacle tips was deemed intrinsic. In polyps, fluorescence in the hypostome, pedicel, and hydrocladia or apparently associated algae was deemed extrinsic. In siphonophores, fluorescence in the somatocyst was deemed extrinsic, as it appeared diffuse throughout the organ, which is known to appear pigmented due to prey (Haddock, pers. obs.). Siphonophore fluorescence in the periphery of the gastrozooid, gonads (eggs), and any unidentifiable part was deemed intrinsic. The observed origin type patterns and an overview of morphological structures are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2, and some exemplary taxa are shown in Figure 3.

Table 1 Observed hydrozoan taxa and associated fluorescent patterns. Number of individuals in parentheses; hydromedusa (H), polyp (P), siphonophore (S), fluorescence number (N), mixed intrinsic and extrinsic fluorescent pattern (M), intrinsic fluorescence pattern (I), and extrinsic fluorescence pattern (E).

| Órden | Subórden | Familia | Especie | Estado | N | M | I | E |

| Anthoathecata | Filifera I | Eudendriidae | Eudendrium sp. 1 | P (1) | x | |||

| Filifera II | Proboscidactylidae | Proboscidactyla sp. 1 | H (4) | x | ||||

| Filifera IV | Pandeidae | Amphinema sp. 1 | H (3) | x | ||||

| Filifera IV | Pandeidae sp. 1† | H (1) | x | |||||

| Filifera IV or III | Oceaniidae | Turritopsis dohrnii † | H (5)/ P (1) | x | ||||

| Bougainvillidae | Bougainvilia rugosa* | H (1) | x | |||||

| Cytaeididae | Cytaeis tetrastyla* | H (1) | x | |||||

| Cytaeis sp. 1† | H (2) | x | ||||||

| Filifera indet. | Filifera sp.1 & 2† | H (2) | x | |||||

| Capitata | Zancleidae | Zanclea sp. 1† | H (1) | x | ||||

| Penariidae | Pennaria disticha | P(1) | x | |||||

| Sphaerocorynidae | Sphaerocoryne sp. 1 | P (1) | x | |||||

| Corynidae | Slabberia strangulata* | H (2) | x | |||||

| Aplanulata | Tubulariidae | Zyzzyzus warreni | P (1) | x | ||||

| Corymorphidae | Corymorpha gracilis* | H (2) | x | |||||

| Corymorpha sp. † | H (1) | x | ||||||

| Anthoathecata sp. 1 & 2† | H (2) | x | ||||||

| Anthoathecata sp. 3† | H (1) | x | ||||||

| Leptothecata | Aequoreidae | Aequorea sp. 1* | H (3) | x | ||||

| Campanulariidae | Clytia linearis | H (2) | x | |||||

| Clytia hemisphaerica | P (1) | x | ||||||

| Clytia sp. 1 & 2 | H (2, 3) | x | ||||||

| Clytia sp. 3 | P (1) | x | ||||||

| Obelia sp. 1 | H (1) | x | ||||||

| Halopteriidae | Halopteris sp. 1 | P (1) | x | |||||

| Lepthothecata sp. 1 & 2 | H (1, 3) | x | ||||||

| Limnomedusae | Gerioniidae | Liriope tetraphylla | H (5) | † | x | |||

| Olindiidae | Gonionemus vertens* | H (3) | x | |||||

| Narcomedusae | Cuninidae | Cunina octonaria* | H (3) | x | ||||

| Siphonophorae | Calycophorae | Abylidae | Enneagonum hyalinum* | S (1) | x | |||

| Ceratocymba dentata* | S (1) | x | ||||||

| Abylopsis tetragona | S (1) | x | ||||||

| Abylidae sp. 1 | S (1) | x | ||||||

| Diphyidae | Diphyes bojani | S (1) | x | |||||

| Muggiaea kochii | S (1) | x | ||||||

| Muggiaea atlantica | S (1) | x | ||||||

| Calycophorae sp. 1-5 | S (1,1,1,1,1) | x |

* Taxa not reported previously in the study area based on information from the following sources: Global Biodiversity Information Facility, Alvariño 1974, Boero et al. 2008, Oliveira et al. 2016, Miglietta et al. 2018, Calder 2019, Schuchert and Collins 2021, and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

† Juveniles only

Figure 2 Anatomy of leptothecate hydromedusa, polyp, and calycophoran siphonophore (anterior nectophore). Possible fluorescence patterns seen in each life stage separated according to likely intrinsic and extrinsic patterns. Abbreviations: gastrovascular cavity (GC), circular canal (CC), radial canal (RC), manubrium (Ma), mouth (M), gonads or gametes (G), tentacle bulb (Tb), marginal tentacle (T), hydrotheca (Ht), gonozooid (Go), gastrozooid (Ga), pedicel (P), and somatocyst (S).

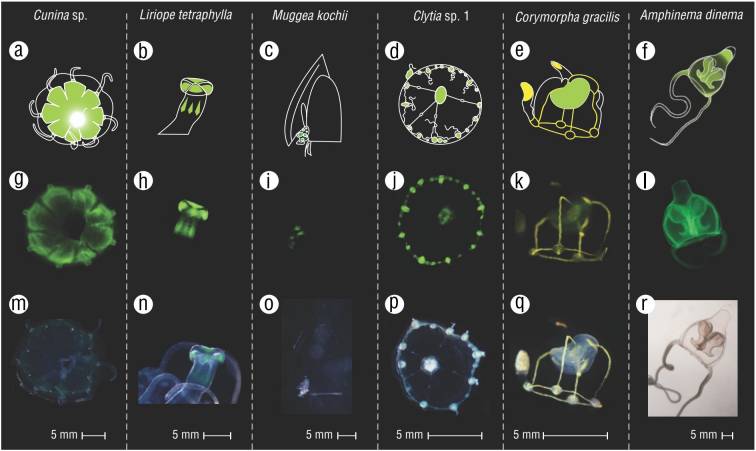

Figure 3 Some examples of observed fluorescence patterns. (A-F) Graphical illustrations of the patterns. (G-L) Images of collected specimens in blue light. (M-R) Images of collected specimens in ambient light.

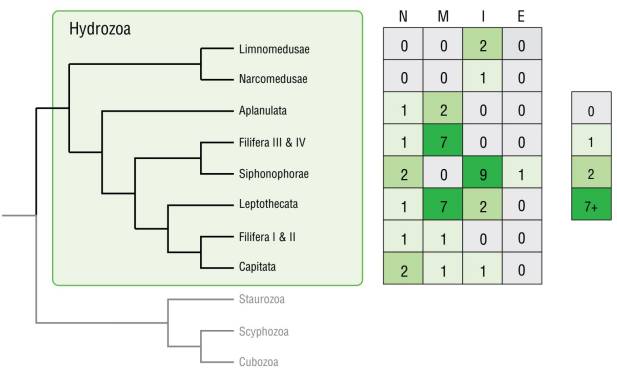

When fluorescence was observed in any morphological structure of the specimen, the anatomical location was noted. The general fluorescence origin type of selected taxa was further mapped onto a general hydrozoan phylogeny based on the phylogenetic analyses of Bentlage and Collins (2021).

RESULTS

Hydrozoan diversity

Seventy-four hydrozoan specimens were examined in this study, spanning 45 hydrozoan species. In total, 20 Anthoathecata, 10 Leptothecata, 12 Siphonophorae, 2 Limnomedusae, and 1 Narcomedusae species were identified, considering polyp and medusa stages (see Table 1 for all taxa). For at least 9 of the observed species, no published records for this region were found (Alvariño 1974, Boero et al. 2008, Oliveira et al. 2016, Miglietta et al. 2018, Calder 2019, Schuchert and Collins 2021, GBIF 2023). At night, a higher abundance of juvenile Anthoathecata specimens was collected, which could only be identified to order or family level. Aequorea sp. was only collected offshore, while Gonionemus vertens was collected under the STRI docks site during the night with the aid of a light source. A complete list of observed taxa, images, and additional details can be found in Supplementary Material 3. Collection sites and additional details for each specimen are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

General fluorescence patterns

Most observed hydrozoans exhibited some form of fluorescence (82%, 37 out of 45 taxa). Differences were observed among the different life stages, with fluorescence detected in 88% (23 out of 26 taxa) of hydromedusae (Leptothecata, Anthoathecata, Limnomedusae, and Narcomedusae) and 50% of hydroids (4 out of 8 taxa in polyp stage observed in this study). Most of the siphonophore taxa fluoresced (83%, 10 out of 12 taxa).

A mixed fluorescence was the most prominent pattern in 44% of the taxa (20 out of 45). Hydromedusae showed the highest presence of the mixed pattern (65%, 17 of 26), and siphonophores showed no mixed patterns. Pure intrinsic fluorescence was present in 33% of all hydrozoan taxa (15 of 45), and pure extrinsic fluorescence was rare (4%, 2 of 45). Only one species, Turritopsis dohrnii, was observed in both its medusa and polyp life stages, and neither stage exhibited fluorescence.

Out of the 23 taxa in the hydromedusa stage that fluoresced, the most common body parts to fluoresce were the manubrium (78%, 18 of 23) and the tentacle bulbs (74%, 17 of 23). Gonads were present in 11 taxa and were fluorescent in 9 taxa. Only 2 species contained non-fluorescent gonads: Obelia sp. 1 and Liriope tetraphylla. The umbrella (6 out of 23), tentacle tips (6), and circular canals (5) were least commonly observed to fluoresce. Tentacles and radial canals fluoresced in a few hydromedusan taxa (3 and 2 out of 23, respectively).

Fluorescence patterns within hydrozoan orders

Athecata

Based on the traditional classification of Hydroidolina and a lack of a comprehensive phylogeny that includes the observed athecate families, we grouped all candidate families into Athecata. However, this group is based on morphological characteristics and is paraphyletic (Bentlage and Collins 2021; Fig. 4). At the order level, Anthomedusae exhibited the widest variety of fluorescent parts, fluorescing in every anatomical category except for the unique oral fluorescence seen in Limnomedusae. Anthomedusae were the only hydromedusae to fluoresce in the umbrella, circular canal, radial canals, tentacles, and tentacle tips. A fluorescent manubrium was shared across all fluorescent athecate medusa. The majority of athecate taxa exhibited fluorescence (75%, 15 of 20) with primarily mixed patterns (90%). The suborder Capitata included the only taxon that showed pure intrinsic fluorescence (the polyp Sphaerocoryne sp. 1) and only one taxon of an unknown suborder showed pure extrinsic fluorescence (Anthoathecata sp. 3). The polyp Zyzzyzus warreni expressed a mixed pattern while the other 3 athecate polyps did not exhibit any fluorescence.

Figure 4 Fluorescence patterns mapped onto a hydrozoan phylogeny based on Bentlage and Collins (2021). Abbreviations: no fluorescence (N), mixed fluorescence (M), intrinsic fluorescence (I), and extrinsic fluorescence (E).

Leptothecata

The majority of the leptothecates fluoresced (90%, 9 of 10 leptothecate taxa), with the one non-fluorescent taxon being a polyp (Halopteris sp. 1). Also, fluorescent leptothecates exhibited primarily a mixed fluorescence pattern (78%, 7 of 9) and 2 taxa showed a pure intrinsic pattern. No taxon showed pure extrinsic fluorescence. Leptomedusae exhibited primarily mixed fluorescent patterns (5 of 7 leptomedusae taxa), and secondarily intrinsic patterns (2 of 7). All leptothecate medusa shared a common fluorescence in the tentacle bulbs.

Fluorescent polyps of this order exhibited mixed patterns of fluorescence. Clytia sp. 3 fluoresced in the pedicel, a pattern it shared with the polyp of Clytia hemisphaerica. Despite this shared fluorescence, the apparent pattern of fluorescence in the pedicel was different between the 2 species: Clytia sp. 3 fluoresced in the entire pedicel, whereas C. hemisphaerica fluoresced in a spotty pattern over the pedicel (Supplementary Material 3). Clytia hemisphaerica was the only reproductive thecate hydroid with fluorescent gonophores.

Siphonophorae

Siphonophorae was the only order that did not have any taxa that expressed mixed fluorescence. Most siphonophores (9 of 12) exhibited pure intrinsic fluorescence, while only one exhibited pure extrinsic fluorescence. The pattern and origin of fluorescence depended on the developmental stage (eudoxid or nectophore). In nectophores, the gastrozooids fluoresced partly when present in all the observed taxa. Also, gonads, when present, were always somewhat fluorescent.

Limnomedusae

Only 2 species of Limnomedusae were collected, and both expressed pure intrinsic fluorescence only. One immature specimen of L. tetraphylla showed no fluorescence. An adult of this species was the only specimen where the oral region distinctly fluoresced in a band. In G. vertens, the oral lips also fluoresced, with additional fluorescence in the tentacle bulbs, gonads, and between the radial canals and manubrium, showing 4 bright, distinct points.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated fluorescence patterns across a variety of hydrozoans in Bocas del Toro, Panama, and explored whether the patterns might provide insights into innate biological factors, including taxonomic relationships, developmental stages, and ecological interactions.

Hydrozoan diversity in Panama

During a 2-week collection period across different coastal habitats, we observed a high diversity of hydrozoans, spanning 5 of 7 taxonomic orders. This study aimed to sample a wide range of hydrozoan species to investigate fluorescence among many different taxa. Due to a lack of specific regional identification literature, many specimens could only be identified to the family or genus level. Furthermore, many juvenile individuals that were collected were missing diagnostic characteristics, which prevented further identification of these specimens. Taxa that could not be assigned to a species could potentially represent an undescribed species, but it was not the aim of this study to specifically investigate this possibility. Our findings, however, highlight the need to conduct further taxonomic studies on hydrozoans in Panama.

Additionally, several species were collected with no published records from the Caribbean coast of Panama, allowing us to add at least 9 new species records for this region (Table 1, Supplementary Material 3). One of the newly recorded species, G. vertens, has not been reported in Central America, thus its occurrence in Bocas del Toro extends its distribution to this region. This globally invasive species was also found in Argentina (Rodriguez et al. 2014) and was likely introduced by cargo ships. All other new records for Panama have been reported previously for the Pacific coast of Panama or neighboring countries. These findings either indicate newly introduced species (e.g., through the Panama Canal from the Pacific to the Caribbean Sea) or are a result of the generally poor taxonomic resolution of tropical hydrozoan diversity.

Observed fluorescence patterns of hydrozoans

The majority of the species in this study (37 out of 45) showed some form of fluorescence, although these patterns varied greatly. We did not find any distinct systematic pattern linking phylogenetic relationships with patterns of origin types (extrinsic and intrinsic) (Fig. 4), but some related taxa shared fluorescent traits pertaining to morphological characteristics and exhibited fluorescence of certain body parts. Phylogenetically informative patterns of fluorescent morphological structures were observed in several orders: Limnomedusae was the only group with distinct fluorescent mouth regions, and all fluorescent Leptomedusae expressed fluorescence in the tentacle bulbs. Fluorescent Anthomedusae always had more than one fluorescent morphological characteristic. Cytaeis and Clytia were the only genera observed in this study with more than one mature fluorescent species, and their pattern was consistent between the species.

Additional information on fluorescence patterns in the scientific literature was only available for 2 genera observed in this study. Specifically, we found that the siphonophore Abylopsis tetragona displays the same gastrozooid pattern as reported for Abylopsis eschscholtzii (Hunt et al. 2012), while the origin and fluorescent pattern observed in Proboscidactyla sp. 1 is consistent with that reported for Proboscidactyla ornata (Kubota 2010).

Within a species, both origin type and morphological structures exhibiting fluorescence were generally consistent when more than one individual was examined. Intraspecific differences were only observed in 2 species and were likely due to the developmental stage, as gonads were commonly observed as fluorescing structures in mature taxa, and a lack of developed tissue can cause a different pattern or non-fluorescence in juvenile specimens. In the limnomedusa L. tetraphylla, early developmental stages have been reported to show fluorescence in various body parts, but not in the oral region (Kubota 2010), suggesting that fluorescence patterns may either change during growth or vary between geographical regions.

We found no variation within the life stages (i.e., polyp and medusa) for corresponding structures in the same species and genera, although we only observed both polyp and medusa stages in T. dohrnii and Clytia spp. in this study. In the case of T. dohrnii, there was no fluorescence at all in either the polyp or medusa stage. We observed several species of Clytia medusa and polyp stages also exhibiting mixed fluorescence, which may indicate that the genus expresses the same fluorescence type across species and across life stages. It should be noted that different endogenous GFP genes are expressed in C. hemisphaerica, depending on the tissue type and life stage (Fourrage et al. 2014).

Fluorescence color

All the observed specimens that showed fluorescence exhibited green fluorescence, except for Corymorpha gracilis, which exhibited green and yellow fluorescent components (Fig. 3, E-Q). Most of the observed green fluorescence is probably due to GFP or GFP-like proteins. In C. gracilis, the yellow coloration within the radial canals and as spots throughout other body parts indicates an acquisition of fluorescent compounds from its food source. For instance, yellow-colored fluorescence can originate from the GFP-homolog yellow fluorescent protein, or it can be present in certain vitamins (Yang et al. 2016) or bacteria (Petushkov et al. 1995). Previous studies in hydrozoans observed multi-colored fluorescence in the leptomedusae Obelia sp. (Aglyamova et al. 2011) and Phialidium sp. (Pakhomov and Martynov 2011).

A red-hued fluorescence was found at the base of Z. warreni polyps, which is most likely caused by symbiotic algae that emit fluorescence (600-700 nm) from algal chlorophyll (e.g., Suggett et al. 2010). This is the first time a relationship has been found between algae and this species, although Z. warreni has been associated with sponges, its preferred substrate (De Campos et al. 2012). No other hues were observed in this study.

Possible ecological roles of fluorescence

The functionality and ecological significance of fluorescence in general remain the subject of speculation and theories for now. It has been suggested that intrinsic color variation may be used in communication, such as for inter-specific signaling (Shagin et al. 2004), as a lure (e.g., Haddock et al. 2005, Haddock and Dunn 2015), to alter the color of bioluminescence, or as a deterrent against predators. Extrinsic coloration, as observed for C. gracilis in this study, may also have specific ecological functions. Yellow fluorescence could be a by-product of the food sources of the medusa (e.g., Francis et al. 2016), or the medusa might actively select specific prey to gain this particular color of fluorescence. Here, we report a distinct fluorescent mouth band (in L. tetraphylla) for the first time, which may have an ecological role as a trait aiding luring or signaling behavior.

Utility of fluorescence patterns as a diagnostic tool

Species identification

Fluorescence patterns could be a valuable complementary diagnostic tool for various biological disciplines, including marine biodiversity assessments. Observing fluorescence patterns may aid in species or higher-level identification due to the high consistency of specific fluorescent morphological structures and body parts within examined taxa (Kubota et al. 2008, Patry et al. 2014). While fluorescence as a single characteristic cannot generally identify a specimen to the species level, it can assist in identifying and resolving the challenges encountered when diagnosing small marine invertebrates such as hydrozoans. Indeed, hydrozoans often lack distinct diagnostic characteristics that can be used for species identification and including fluorescence as an additional trait may aid in overcoming this challenge.

Biodiversity monitoring and surveys

Utilizing fluorescent properties can improve efforts to monitor and survey hydrozoans and other fluorescent marine invertebrates. By detecting fluorescence, especially in highly transparent and small specimens, the processing time can be greatly reduced. Using blue or UV light can make medusae or small polyps visible in large plankton samples or settling panels. However, it cannot be used as a quantitative method since non-fluorescent specimens will be neglected. For example, polyps of the hydrozoan species Olindias formosus were detected for the first time using the fluorescence of the medusa buds on hydroids (Patry et al. 2014). Additionally, intrinsic fluorescence has been successfully used to detect Porifera and Anthozoa recruits on settling panels (Steyaert et al. 2022). Our findings emphasize that fluorescence patterns may also be a useful tool for marine pelagic surveys and should be further developed as a method to detect commonly overlooked taxa such as hydrozoans.

A clue for ecological interactions

Visualizing fluorescence properties, which are usually not obvious to the naked eye without specific equipment, can also help in detecting ecological interactions. For example, we were able to display some yet unknown ecological relationships such as the fluorescent algae at the base of Z. warreni polyps. Furthermore, differences in extrinsic patterns, as observed for Corymorpha, may indicate deviations in food intake among different developmental stages. The high prevalence of extrinsic patterns also underscores the likely strong interaction between symbionts and the presence of prey-predator fluorescence uptake.

Limitations

Although fluorescence patterns may hold notable information about species identity, ecology, and development, studying this property comes with challenges and limitations. Here, a lack of information on species coverage and diversity, limited knowledge regarding phylogenetic relationships, and specimen fragility limits further conclusions regarding the prevalence of fluorescence patterns and their diagnostic value. Due to the lack of information on species distributions across the Caribbean coast of Panama, many specimens were identified only to taxonomic levels of genus or higher (27 of 45). Additionally, the ongoing debate of phylogenetic relationships within hydromedusae makes systematic inferences difficult. A better resolved hydrozoan phylogeny could clarify the evolutionary origins and diversification of fluorescent patterning in this group.

In this study, we provide new insights into the diversity of fluorescence patterns in hydrozoans and explore its value as a diagnostic tool. We observed a wide range of fluorescence patterns across 5 hydrozoan orders and identified some consistent taxa-specific fluorescent features in certain body parts. Our findings suggest that the ecological relevance of fluorescence interactions in hydrozoans is stronger than previously known, given the high variation in intrinsic and extrinsic fluorescence patterns across species and anatomical structures. However, further research is needed to understand the precise mechanisms driving these patterns and their ecological and evolutionary significance. To address these questions, we recommend conducting integrative plankton and blue-water biodiversity surveys, particularly in less surveyed regions like Panama, incorporating classical morphological traits and genetic analyses. A better-resolved hydrozoan phylogeny would also aid in understanding the evolutionary context of these traits. Future studies could explore the links between fluorescence and other aspects of hydrozoan biology, such as life history, behavior, and ecological interactions. Finally, we note that fluorescence may be a useful characteristic when analyzing marine invertebrate groups beyond hydrozoans and should be further explored. Our study underscores the need for a more comprehensive approach to assess and monitor marine biodiversity in general and suggests fluorescence patterns as a potential additional tool to shed light onto previously overlooked yet informative traits.

texto en

texto en