Mangrove forests grow in the intertidal zone on tropical and subtropical coasts (Lugo & Snedaker 1974, Feller & Sitnik 1996). Consequently, mangrove species can tolerate a wide range of salinities and flooding that, together with other factors, such as topography, soil physiochemistry and mineral nutrients, result in diverse types of forests with different canopy height and species composition (Lugo & Snedaker 1974, López-Portillo & Ezcurra 2002). For instance, in the Yucatan Peninsula, which host 54.5 % of the total area occupied by mangroves in Mexico (Rodríguez-Zúñiga et al. 2013), there are different mangrove types, such as fringe, basin, scrub, and peten (Zaldívar-Jiménez et al. 2010). In all types of mangrove forests, Rhizophora mangle L. can occur with a contrasting structure: tall trees in the less saline fringe mangrove and shorter trees in the hypersaline scrub mangrove (Zaldívar-Jiménez et al. 2004). Scrub mangrove plants are supposedly short because of several complex abiotic factors such as salinity, flooding, redox potentials, and mineral nutrient availability (Lugo & Snedaker 1974, Feller et al. 2003, Lovelock et al. 2006), but data of salinity and phosphorous in sediments presented in several tall and scrub mangrove forests are contradictory (Cisneros-de la Cruz et al. 2018).

The different types of mangroves show specific adaptive strategies, according to the environmental conditions in which they grow (Feller 1996, Robert et al. 2009, Yáñez-Espinosa & Flores 2011). For example, some studies have shown that scrub mangrove have less photosynthetic efficiency, gas exchange and hydraulic conductivity than fringe mangroves (Lin & Sternberg 1992, Lovelock et al. 2006, Naidoo 2010). This occurs because, in the hypersaline environment, plants experience long periods of physiological drought (Yáñez-Espinosa et al. 2001, López-Portillo et al. 2005, Schmitz et al. 2006a). In any case, one of the most critical tradeoffs is to reconcile efficient water transport with security against cavitation, which means the obstruction of the conducts because of the formation of air bubbles (Schmitz et al. 2006b, Xiao et al. 2009). Then, study of the hydraulic architecture of this mangrove species would improve the understanding on the mechanisms of water movement, under extreme saline environments, and its responses to environmental changes (Tyree & Ewers 1991, Cruiziat et al. 2002, McCulloh & Sperry 2005).

Adaptations in hydraulic architecture in mangrove trees can be key in regulating their distribution, survival, and growth (Tyree & Ewers 1991, Valladares et al. 2004); and are especially relevant at the seedling stage when individuals are more vulnerable to environmental variability (Cornelissen et al. 1996, Ishida et al. 2005, Marks 2007, Krauss et al. 2008). However, only one study has focused on the physiological and anatomical strategies during different life stages (Farnsworth & Ellison 1996).

Since mangroves are constantly exposed to anthropic and natural impacts that rapidly diminish their natural distribution (Alongi 2002), the characterization of hydraulic architecture strategies from seedlings to adults under contrasting environments could strengthen management actions toward their restoration and conservation. It is expected that scrub mangroves growing under a more saline environment will exhibit more secure hydraulic strategies than fringe mangroves at both life stages, seedling, and adult. The objective of this study was to compare the anatomical and physiological attributes of stem hydraulic architecture of seedlings and adults of Rhizophora mangle L. in the contrasting environments of a scrub and fringe mangrove forests in Celestún, Yucatan, Mexico.

Materials and methods

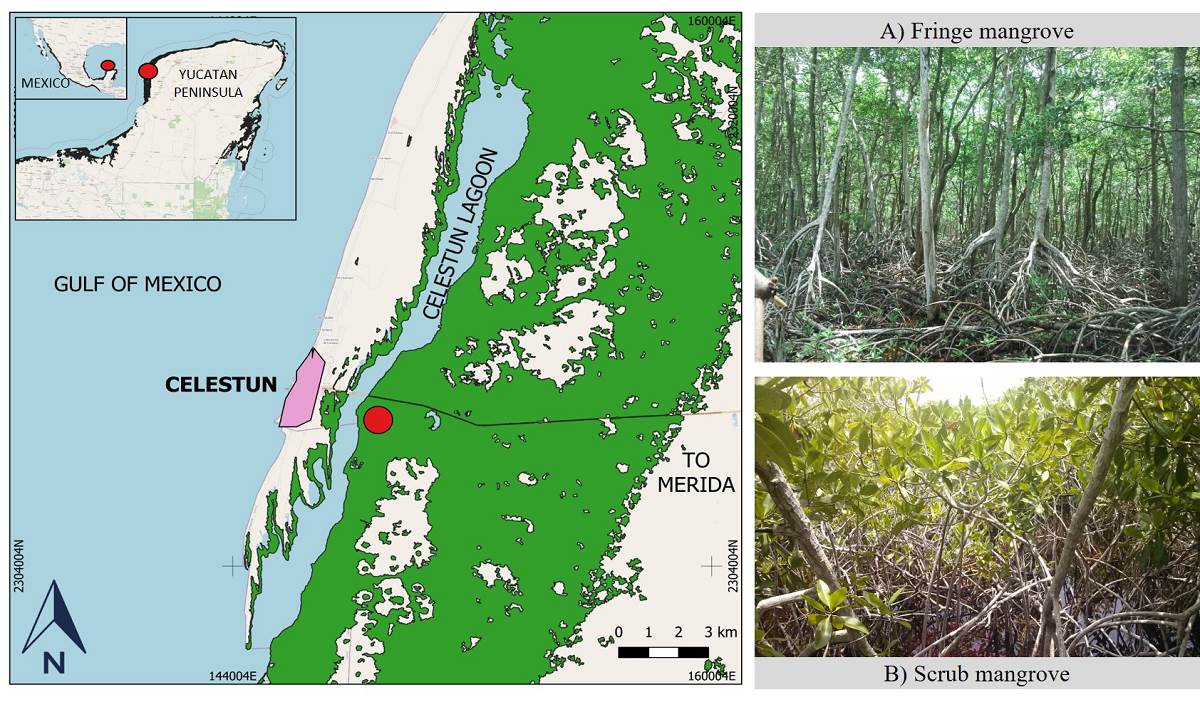

Study area and microenvironment. The study was performed in the Ria Celestún Biosphere Reserve located at the northwest of the Yucatan Peninsula (Figure 1). The climate is warm semi-arid with a mean annual temperature of 28.5 °C, annual mean precipitation of 760 mm, and characterized by three seasons: dry (March-May), rainy (June-October) and early dry (locally named “nortes”; showing dispersed rain events, November-February) (Zaldívar-Jiménez et al. 2010). The tidal regime characteristic is a mixed semidiurnal tide of 0.6 m (Herrera-Silveira 1994). Two sampling points were chosen and correspond to two types of mangroves with contrasting morphology and environmental conditions; their location was based on the study area of Zaldívar-Jiménez et al. (2004) and on sites included in the Mexico Mangrove Monitoring System (Herrera-Silveira et al. 2014). The fringe mangrove (Figure 1A: 20° 51' 22.7'' N; 90° 22' 37.7'' W) was located at the edge of the lagoon, where trees were 16.3 ± 4.8 m tall, and had a diameter at breast height (dbh) of 22.9 ± 7.2 cm, and a density of 1,583 trees ha-1. The scrub mangrove (Figure 1B: 20° 51' 04.9'' N; 90° 22' 22.9'' W) was located 0.72 km inland from the lagoon, where trees were 2.8 ± 1 m tall, had a dbh of 3.4 ± 1.5 cm, and a density of 15,600 trees ha-1.

Figure 1 Location of the study site and mangrove forests in the Ria Celestún Biosphere Reserve, Yucatan, Mexico.

Rhizophora mangle L. is a viviparous angiosperm, with high ecological importance, which shows great plastic phenotype and can grow in a range of salinity of from 0 to 90 ‰ (Tomlinson 2016). For the two-mangrove type selected, two plant stages of R. mangle were considered: seedlings, individuals with visible propagule of < 50 cm height and diameter < 1 cm, with 10 - 20 leaf scars to ensure similar ages (Duke & Pinzon 1992); and adults, individuals from 2 to 4 m height and from 2.5 to 3.5 cm dbh. Sampling was achieved within a three-month period during the rainy season.

Microenvironment was simultaneously characterized in the understory at both sites and on one reference point above the canopy during a week in July, August, and October 2013. Air temperature and relative humidity were recorded with a Temp Smart Sensor (S-TMB-M003, Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, MA), and photosynthetic photon flux (PPF) with a quantum sensor (Photosynthetic Light Smart Sensor, S-LIA-M003, Onset, Bourne, MA). Variables were recorded simultaneously every 10 s and 10-min averages were stored with a data acquisition system (HOBO U30-NRC Weather Station Starter Kit, Onset, Bourne, MA), such interval allows to save representative information of the microenvironmental changes without saturating the datalogger memory. Vapor pressure deficit (VPD) was estimated after Jones (2013). During each microenvironment measurements, interstitial water was sampled with an acrylic tube connected with a syringe to measure interstitial salinity (~ 30 cm depth) using a portable conductivity meter (Model 30, YSI, Yellow Springs, OH) at three random points per site. At each point, one soil sample were collected at equal depths with a PVC tube and a plunger, stored on ice within plastic bags and carried to the laboratory where soil water potential (Ψsoil) was measured with a dew point potentiometer (WP4, Decagon Devices Inc., Pullman, WA).

Physiological measurements. For all plant measurements, five individuals of R. mangle, per life stage and site, were considered. Three fully developed leaves were collected from every individual to measure water potential at pre-dawn (maximum water potential; Ψpredawn) and noon (minimum water potential; Ψmidday), with a dewpoint potentiometer (WP4, Decagon Devices Inc., Pullman, WA). To measure the hydraulic conductivity (kh; kg m-1 MPa-1), individuals were removed, covered with wet towels and plastic. Segments 20 cm long were measured with a hydraulic conductance and flow meter in the transient mode (HCFM, Dynamax, Houston, TX), according to Sperry et al. (1988). The specific hydraulic conductivity (ks; kg m-1 s-1 MPa-1) was obtained as the ratio between kh and xylem area (Melcher et al. 2001).

Anatomical characterization. After measuring the hydraulic conductivity, samples for each stage and site were fixed in FAA (formaldehyde, ethanol 96 °, glacial acetic acid, water 10: 35: 5: 50) (Ruzin 1999); and, after two days, washed with tap water and stored in GAA (glycerin, 96 ° ethanol, water 1: 1: 1) until sectioning. Subsequently, smaller segments were extracted from the center of the samples and using a sliding microtome (GSL1, Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, Birmensdorf, Switzerland), 50 µm thick transverse sections were obtained. Tissue sections were stained with safranin-fast green (Ruzin 1999) and mounted in permanent slides with synthetic resin. Sections were analyzed with a light microscope (DM2000, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and digital images of tree fields for each slide were taken with an integrated camera Olympus U-CMAD3, equipped with the program Infinity Analyze (release v5.0.2; Lumenera Corp., Canada). The measurements were carried out with the ImageJ (v1.49c; National Institutes of Health, USA) in three visual fields of each image captured. The tangential and radial diameter of the vessel lumen, the thickness of the vessel wall and vessel density were measured. The area of the vessel lumen (VLA) was calculated using the equation for an oval area as

Data analysis. Nested analyses of variance were performed to compare the means of the anatomical and physiological variables between life stages and sites; stage was considered nested within mangrove type. Duncan post-hoc tests were done to identify significant differences among means (P < 0.05). Shapiro-Wilk's tests were used to assess whether data distribution was normal, and Levene’s tests were used to test for homoscedasticity. Data without normal distribution or homoscedasticity were transformed with natural logarithm or reciprocal transformations. When normal distribution for the data was not achieved (grouping vessels) a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. All analyzes were performed in STATISTICA 7 (StatSoft, Tulsa, USA). To distinguish the variables that contribute the most to the variance of groups, a canonical discriminant analysis (CDA) was performed using the physiological and anatomical variables that did not present multicollinearity (vessel density, lumen area and length of the vessel, % of solitary vessels, specific hydraulic conductivity, and maximum and minimum leaf water potential). Also, a canonical correlation analysis (CCA) was performed with the most relevant discriminant variables; the physiological and anatomical variables as dependent variables (vessel density, specific hydraulic conductivity, vessel area, and maximum and minimum leaf water potential), and the microenvironmental variables (salinity and maximum VPD) as independent variables. The multivariate analyzes were performed with XLSTAT v7.5.2. (Addinsoft, France).

Results

Microenvironment. Fringe and scrub sites showed contrasting microenvironments during the study period. The fringe mangrove site had lower average salinity (25.84 ± 2.75 ‰) and higher soil water potential (Ψsoil; -0.30 ± 0.2 MPa) than the scrub mangrove site (51.42 ± 2.28 ‰ and -1.91 ± 0.94 MPa, respectively) (P < 0.05). Maximum vapor pressure deficit (VPD) in the understory was lower in the fringe mangrove site (1.38 ± 0.12 kPa) than in the scrub mangrove site (1.83 ± 0.12 kPa; P < 0.05). Also, the understory of the fringe site received less daily photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD; 2.28 ± 0.2 mol m-2 d-1) than that of the scrub site (5.85 ± 0.54 mol m-2 d-1). The reference point above the canopy received up to ten times more PPFD than the understory of both sites (45.2 ± 2.46 mol m-2 d-1). However, VPD values in the scrub site were like those registered above the canopy (Table 1).

Table 1 Microenvironment of scrub and fringe mangrove understory and above the canopy in Celestún, Yucatan, Mexico. Data are means ± standard errors.

| Mangrove type | Temperature (°C) |

Relative Humidity (%) |

Photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) (mol m-2 d-1) |

Mean vapor pressure deficit (VPD) (kPa) |

Soil water potential (Ψsoil) (MPa) |

Interstitial salinity (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scrub | 27.7 ± 3.2 | 76.8 ± 9.5 | 5.8 ± 0.54 | 0.94 ± 0.57 | -1.91 ± 0.94 | 51.42 ± 2.28 |

| Fringe | 27.0 ± 2.5 | 79.5 ± 7.5 | 2.28 ± 0.2 | 0.78 ± 0.41 | -0.30 ± 0.2 | 25.84 ± 2.75 |

| Above the canopy | 27.5 ± 3.4 | 76.9 ± 10.5 | 45.2 ± 2.46 | 0.94 ± 0.61 | - | - |

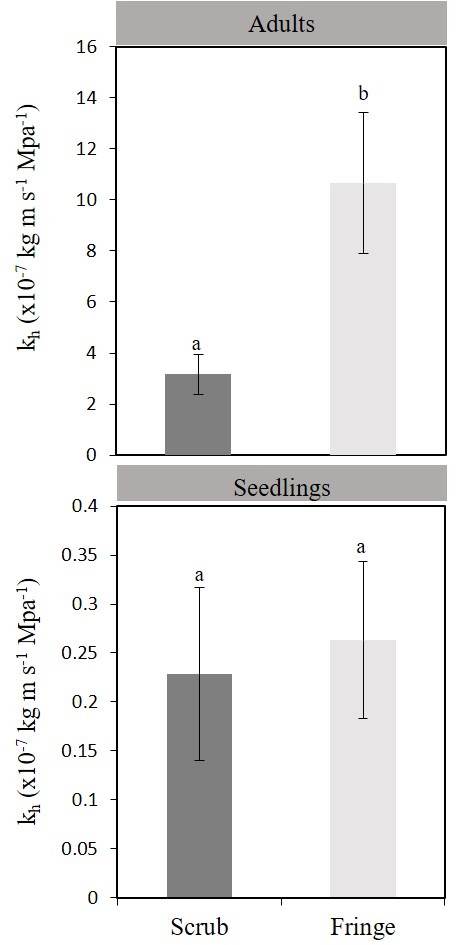

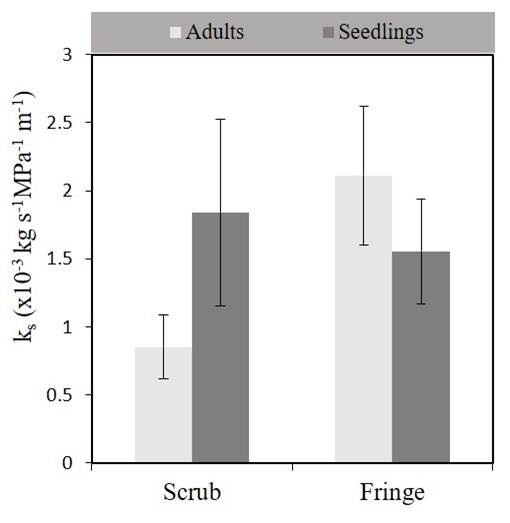

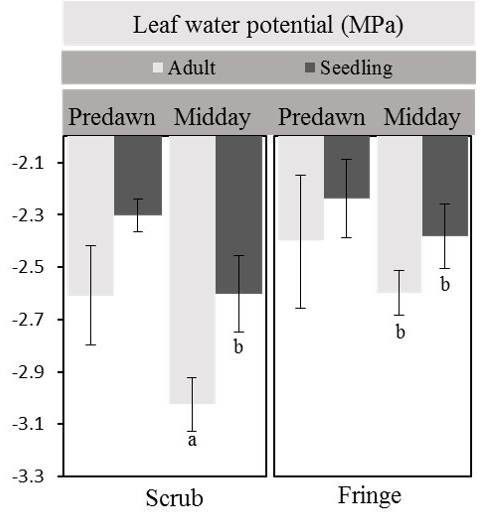

Physiological responses. Hydraulic conductivity (kh) was higher for adults in the fringe forest (1.06 ± 0.3 kg m s-1 MPa-1) than that for adults in the scrub mangrove (0.32 ± 0.07 kg m s-1 MPa-1) (F 1, 2 = 6.93, 14.13; P < 0.05; Figure 2). Differences in kh were also found between life stages in the fringe forest (P < 0.05). Specific hydraulic conductivity (ks) of plants was not different between life stages within each forest nor between forest types (F 1, 2 = 1.7, 0.87; P > 0.05), but fringe adults, and fringe and scrub seedlings, had a tendency of higher ks values than shrub adults (Figure 3). Although the Ψpredawn was not different for plants at any site or stage, the Ψmidday of scrub adults was the lowest (Duncan test, P < 0.05; Figure 4).

Figure 2 Hydraulic conductivity (kh) of seedlings and adults of Rhizophora mangle in scrub and fringe mangrove. Different letters indicate significate differences between sites and stage (P > 0.05). Data are means ± standard errors (bars indicate standard errors).

Figure 3 Specific hydraulic conductivity (ks) of seedlings and adults of Rhizophora mangle in scrub and fringe mangrove (P < 0.05). Data are means ± standard errors (bars indicate standard errors).

Figure 4 Predawn and midday values of foliar water potential of seedlings and adults of Rhizophora mangle from fringe and scrub mangrove. Different letters indicate significant differences in midday leaf water potentials between stages and sites (P < 0.05). Data are means ± standard errors (bars indicate standard errors).

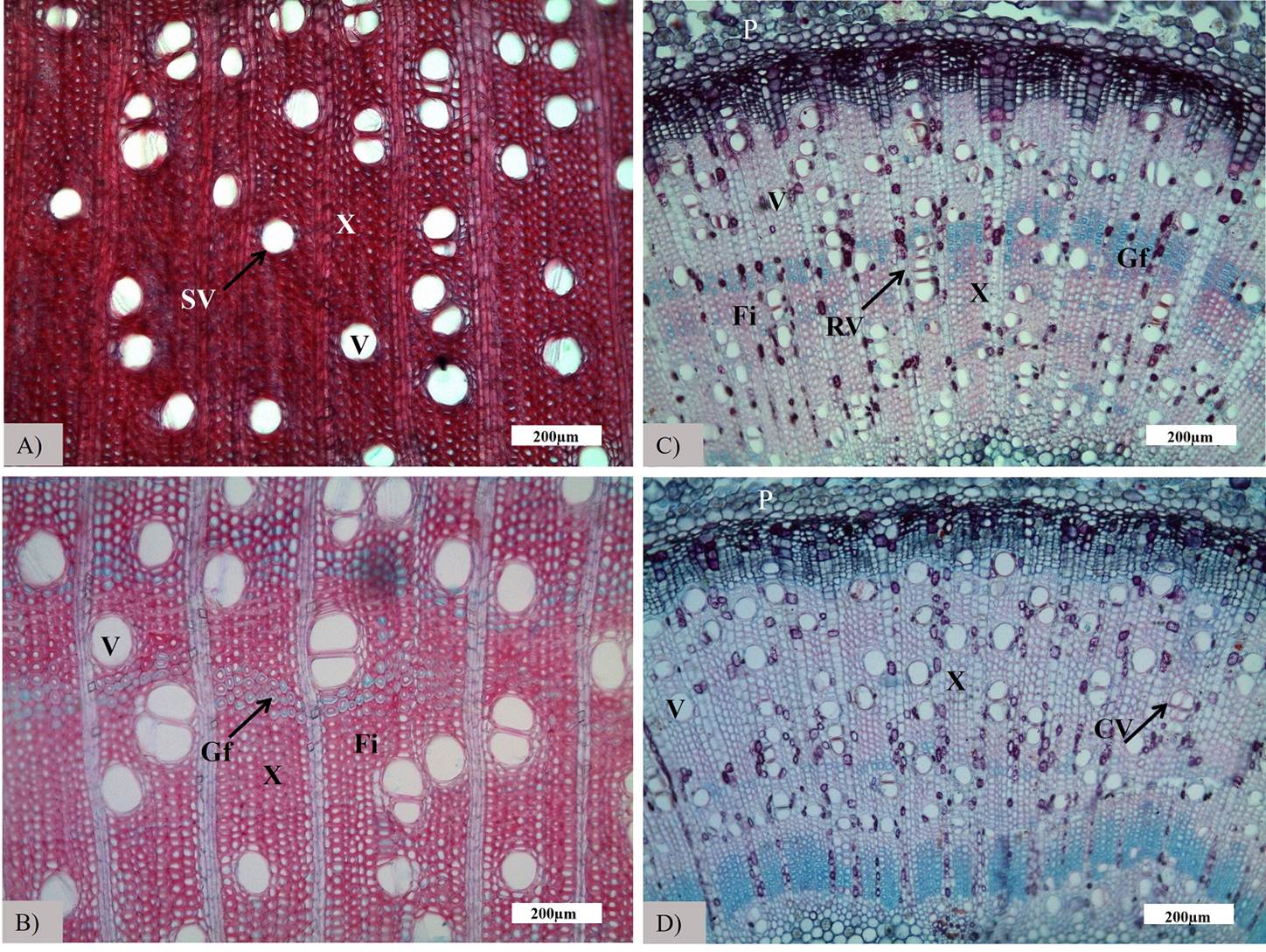

Anatomical traits. Adults and seedlings of R. mangle had different anatomical stem structures. At seedling stage, stems showed secondary growth without significant differences in vessels characteristics between scrub and fringe mangrove forest (Figure 5; Table 2). Seedlings had an average vessel density of 103 ± 35 v/mm2, with a tangential and radial diameter of 37.75 ± 6.53 µm and 41.83 ± 7.55 µm, respectively; vessels were mostly solitary (65.43 %) and vessel clusters less frequent (12.35 %). Compared to adults, seedlings had differences in anatomical characteristics related to the allometric relationship of their respective growth stages (Figure 5), smaller vessels, but in a greater density than in adults (Table 2). Adults in fringe mangrove had lower vessels density (94 ± 6 v/mm2) than adults in scrub forest (111 ± 7 v/mm2) (P > 0.01). Also, the vessel grouping pattern observed was different between forest types, with a higher percentage of solitary vessels in the fringe, and higher radial multiple vessels in the scrub (Table 2). Furthermore, vessel lumen area and radial diameter were higher for adults in the fringe than in the scrub mangrove (F 1 = 16.5, 6.4, P < 0.05).

Figure 5 Transversal sections of stems of seedlings and adults of Rhizophora mangle in fringe and scrub mangrove: A) adult scrub; B) adult fringe; C) seedling scrub; and D) seedling fringe (V, vessels; X, xylem; P, phloem; Fi, fibers; Gf, Gelatinous fibers; SV, solitary vessels; RV, vessel radial multiples; CV, vessel clusters).

Table 2 Anatomical vessel variables for seedlings and adults of Rhizophora mangle from the scrub and fringe mangrove. Data are means ± standard errors. Different letters indicate significant differences within rows (Duncan test, P < 0.05).

| Variables | Scrub | Fringe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | Seedling | Adult | Seedling | |

| Vessel density (v/mm2) | 32 ± 1 a | 934 ± 6 b | 19 ± 1 a | 111 ± 7 b |

| Tangential diameter (µm) | 72.1 ± 2.3 a | 37.8 ± 1.0 b | 84.0 ± 2.2 a | 37.7 ± 1.3 b |

| Radial diameter (µm) | 70.4 ± 3.8 b | 41.1 ± 1.4 c | 89.7 ± 3.8 a | 42.5 ± 1.4 c |

| Wall thickness (µm) | 6.0 ± 0.2 a | 3.8 ± 0.1 b | 5.3 ± 0.2 a | 3.7 ± 0.1 ab |

| Lumen area (µm2) | 3807 ± 178 b | 1122 ± 60 c | 5609 ± 284 a | 1136 ± 68 c |

| Length (µm) | 905.5 ± 26.0 a | 611.0 ± 16.1 b | 926.1 ± 21.2 a | 622.6 ± 17.9 b |

| % Solitary vessels | 54.5 ± 3.7 a | 70.7 ± 4.8 ab | 72.2 ± 5.1 b | 58.8 ± 4.7 ab |

| % Cluster’s vessels | 14.7 ± 3.1 a | 10.7 ± 3.6 a | 11.9 ± 3.8 a | 14.0 ± 3.5 a |

| % Radial multiples vessels | 31.6 ± 4.2 a | 18.5 ± 4.5 ab | 15.9 ± 4.3 b | 30.0 ± 4.5 ab |

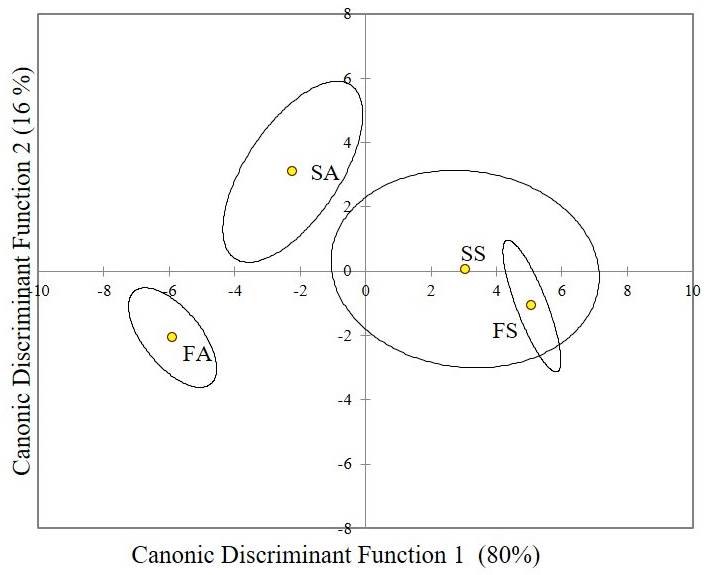

Multivariate analysis. According to the CDA, the first discriminant function explained 80 % of the total variance and the second 16 % of the remaining variation. The first function explained the differences in adult and seedling stages defined by the vessel density, vessel lumen area, and ks; while the second explained the differences between fringe and scrub mangrove forest through the Ψpredawn and Ψmidday (Figure 6) (Wilk's λ = 0.003, n = 120, P < 0.005). The correlation of environmental, physiological, and anatomical variables in the CCA was explained with 62 % in the first canonic correlation (0.94, P < 0.001). The canonical correlation analysis also showed a negative relationship between hydraulic conductivity and vessel lumen area with salinity (Table 3); also, it showed that Ψmidday and vessel density were negatively related to VPD.

Figure 6 Canonical Discriminant Analysis for anatomical and physiological variables of seedlings and adults of Rhizophora mangle in fringe and scrub mangrove forests. Wilk’s λ = 0.003, P > 0.005. FA: fringe adults; SA: scrub adults; FS: fringe seedlings; SS: Scrub seedlings.

Table 3 Anatomical and physiological variables used in the canonical discriminant analysis and their partial contribution expressed by the standardized coefficients of the canonical functions. Letters represent the variables with more contribution in centroids separation.

| Variables | Correlation of original and canonical variables |

Standardized canonical coefficients |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomical | ||

| Vessel density | 0.63 | 0.11 |

| Lumen vessel area | -0.82 | -0.88 a |

| Physiological | ||

| Specific hydraulic conductivity (ks) | -0.82 | -0.19 |

| Predawn leaf water potential (Ψpredawn) | 0.03 | -0.34 |

| Midday leaf water potential (Ψmidday) | -0.10 | -0.49 |

| Environmental | ||

| Maximum vapor pressure deficit (VPDmax) | -0.33 | -0.97 |

| Salinity | 0.59 | 1.13 a |

Discussion

Seedlings and adults of Rhizophora mangle showed physiological and anatomical strategies in the hydraulic conduction system that allowed them to respond to the contrasting environments in which they developed. While the fringe mangrove is in continuous contact with the water body, under salinity values close to those of the lagoon; the scrub mangrove, in the inland zone, has higher and variable salinity values, which are regulated by the sporadic high tide and rain events (Lugo et al. 2007, Herrera-Silveira 1994). This explained the differences in salinity and Ψsoil of both sites (Table 1). The higher daily photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) in the understory of the scrub mangrove, compared to the fringe mangrove, also caused higher temperature and vapor pressure deficit (VPD) values, which were closer to the reference value above the canopy (Table 1).

In these contrasting environments, salinity explained most of the variance in hydraulic architecture of both, seedling, and adult stages, within the canonical correlation analysis (CCA). This agrees with previous studies showing that salinity is one of the most important factors influencing the health, distribution, growth, and productivity of mangroves (Ball 2002, Krauss et al. 2008). In scrub mangroves, the high salinity, lower soil water potential, and high vapor pressure deficit exert negative pressures on the hydraulic systems that guarantee the water flow from roots to leaves (Jones 2013, Reef & Lovelock 2015), which is reflected in the inverse relation of VPD and the Ψmidday in the CCA (Table 3). However, although this increase in pressure within the vessel could form air bubbles that lead to the cavitation vessel in the water column and the consequent reduction of hydraulic conductivity (Sobrado 2007), the narrower vessels and thicker walls, observed in scrub mangroves (Figure 5), would offer greater mechanical strength to resist strong negative pressures (Baas et al. 1983, Guet et al. 2015). In fact, salt exclusion mangroves, as R. mangle have the highest cavitation resistance reported for angiosperm trees (Jiang et al. 2017).

The maintenance of the water column continuity is crucial to ensure water supply to leaves and allowing carbon gain for plant growth and survival (Tyree 2003). It has been observed that larger stems are related to wider vessels that ensure hydraulic efficiency through the water column (Rosell et al. 2017). This relation was also observed in this study: wider vessels in fringe adults, with larger stems and water columns, than in shorter stems of individuals of the scrub mangrove. Despite vessel length did not have significant differences between mangrove types (Table 2), a tendency was observed with shorter vessels in scrub mangrove that allow a safer water transport system, and larger vessels in fringe mangrove that resulted in a more efficient water transport (Cruiziat et al. 2002, Gil-Pelegrín et al. 2005). Moreover, the higher vessel density and grouping observed in scrub adults and seedlings of both mangrove types, showed in Figure 5, would allow greater redundancy and, therefore, greater safety against embolisms (Cruiziat et al. 2002, Ewers et al. 2007). These characteristics provide safer hydraulic conductivity but imply a tradeoff with an efficient water flow capacity of each vessel according to the Hagen-Poiseuille law (Tyree & Zimmermann 2002). This inverse relation of hydraulic conductivity with vessel lumen area and salinity was sustained by the CCA (Table 3). Conversely, the low density, wide vessels, and thin vessel walls of fringe mangroves, would allow a more efficient water transport, but high vulnerability to vessel cavitation. These results agree with Lin & Sternberg (1992), who recorded lower CO2 assimilation and higher water use efficiency on scrub mangroves than fringe mangroves. Yet, seedlings of both types of mangroves had similar hydraulic architecture, with high density, smaller and more clustered vessels that confer a safer, but a less efficient system, with hydraulic conductivity (kh) values well below those of adults (Figures 2, 5).

The lower hydraulic conductivity in seedlings compared to adults highlight the relevance of a safe conducting system at this life stage, even if seedling establishment is generally favored by a greater growth and biomass production (Donovan & Ehleringer 1991). However, a safer conducting system requires higher carbon investment, which implies an additional cost, diminishing growth rates (Ball et al. 1997, Sobrado & Ewe 2006, Jiang et al. 2017). Low hydraulic conductivity is associated to low photosynthetic rates, concordant with the low stomatal conductance observed in scrub mangroves (Ball & Farquhar 1984, Shiau et al. 2017). Moreover, this safer hydraulic system could provide seedlings a greater chance of survival in a variable saline environment until the reproductive stage (Donovan & Ehleringer 1991). Although it has been suggested that seedlings show high plasticity (Farnsworth & Ellison 1996, Biber 2006), in this study no differences were observed in the hydraulic architecture at this stage despite significant microenvironmental differences in the sites they grew. This could be explained by the viviparity of R. mangle (Tomlinson 2016): the propagule is an important carbohydrate reservoir, which the seedlings can use differentially during the first stage of growth according to the specific conditions in which they develop (Smith & Snedaker 2000). Consequently, storage reserves are temporarily available for propagules to buffer from either flooding, salinity and/or variability in resource availability that may otherwise affect photosynthesis and growth (Smith & Snedaker 2000, Dissanayake et al. 2014, Lechthaler et al. 2016).

One of the changes in water transport strategies related to the growth stage of R. mangle is the differences in leaf minimum water potential, as the canonical discriminant analysis (CDA) showed (Figures 4, 6). The leaf water potential of adults at both sites was contrasting, with lower values in scrub compared to fringe adults, which ensures a pressure gradient for water transport in the more saline environment of the scrub mangrove (Melcher et al. 2001, Naidoo 2010, Reef & Lovelock 2015). In contrast, in seedlings, no differences among scrub and fringe were observed, but seedling leaf water potential was higher than that for adults. The higher water potential in seedlings could mean that at this stage, both propagule and leaves are important water reservoirs (Lechthaler et al. 2016). The access to water reserves could also explain the similarity in the xylem structure and hydraulic conductivity at both sites for the seedling stage (Ball 1988, Melcher et al. 2001, Hao et al. 2009). However, the water transport strategies could change for seedlings as they grow, as it has been observed by Kodikara et al. (2017) in seedlings of six mangrove species, implying that adaptation to salt and physiological needs of mangrove seedlings vary with age.

Differences in the hydraulic architecture of the two studied stages of scrub R. mangle highlight the relevance of the propagule itself and the growing season in which it is established. It has been reported that the balance of reserves and photosynthetic function of the propagule can change depending on the environment in which seedlings develops (Smith & Snedaker 2000). Thus, seedlings that grow in lower salinity conditions, such as those of the fringe forest, can waive the propagule reserves and obtain carbon from photosynthesis (both from the propagule green tissue and from its developing leaves). In contrast, in places where environmental conditions limit photosynthesis and hydraulic conductivity (Naidoo 2006, 2010), such as the scrub mangrove, seedlings can use these reserves for their growth. Furthermore, strategies regarding hydraulic architecture in seedlings could depend on the specific season in which they were established (Dissanayake et al. 2014, Schreel et al. 2019, Guillén-Rivera et al. 2021). These results also highlight the importance of a correct choice or season for reforestation on restoration projects and the importance of seasonal influx of water for successful seedling establishment.

It is possible that at the seedling stage, specific hormonal signals are generated according to the microenvironment and, consequently, these signals can be critical for the formation of a conduction system that guarantees an efficient or safe water flow once the seedling has matured, and the hypocotyl reserves have been exhausted (Farnsworth & Ellison 1996, Farnsworth 2004). Developing an adequate hydraulic architecture according to the microenvironment is essential to survive in fluctuating environmental conditions such as those found in mangrove forests (Ball 1988, 2002, Yan et al. 2007, Wang et al. 2011). Thus, fringe seedlings ultimately develop an efficient conduction system that allows larger trees to grow larger vessels and greater hydraulic conductivity, while scrub seedlings maintain a safe conduction system throughout their lifetime, even at the cost of limiting their growth.

Although salinity was the most important factor in this study for the differences in hydraulic architecture for plants in the two sites, other factors such as hydroperiod or nutrient availability, which play a significant role in the development of functional strategies of mangrove species (Feller et al. 2010) were not considered and should be explored in further studies. A greater understanding of the hydraulic architecture at different life stages allows the development of more exact models on the structure and dynamics of mangrove forests (Ellison & Farnsworth 1997, Vargas-Cruz et al. 2019, Peters et al. 2020), which can be beneficial for diagnosing their health and for management actions relevant to their restoration and conservation.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)