Introduction

The Gulf of California is home to little-exploited natural beds of the mussel Modiolus capax (Conrad, 1837) with fishery and aquaculture potential; specifically in Mexico, this species is classified as a commercially important fishery resource (López-Carvallo, 2015). This mussel is widely distributed across the eastern tropical Pacific and Gulf of California (De la Rosa-Vélez et al., 2000). There are studies on the habitat and geographical distribution of M. capax (Coan & Carlton, 1975; Keen, 1971). In addition, characteristics of different development stages and preference for certain substrates for larval settlement (Aguirre-Hinojosa, 1987; Farfán et al., 2007) have been described with larvae produced in the laboratory (Orduña-Rojas & Farfán, 1991; Farfán et al., 2007). Size structure, growth, and recruitment of two populations living in the Gulf of California have also been investigated, finding variability in both recruitment and size structure (Garza-Aguirre & Bückle-Ramírez, 1989b). Moreover, changes in the reproductive cycle of this species associated with temperature and food availability have been reported (Farfán & Espinoza-Peralta, 1998), as well as differences in the reproductive cycle in different localities (Ochoa-Báez, 1985).

Some species, such as Mytilus edulis (Linnaeus, 1758), show significant inter-annual variations in the spawning season associated with environmental changes, which in turn affect larval recruitment (Avendaño et al., 2011). For some bivalves, reproductive periodicity depends on intrinsic factors such as genetic, physiological, and nutritional characteristics, and environmental conditions, which can determine timing and maturation stages, duration, and the synchronous spawning in a given population (Newell et al., 1982). In this regard, mytilids’ temperature and food availability are known to influence gonadal development from early stages to gamete release (Bayne, 1976). On the other hand, variations in the production of cultured mussels and other mollusk might be related to inter-annual variations in gonadal development caused by environmental changes (Maeda-Martínez, 2008; Cantillánez et al., 2005). For this reason, the study of reproductive strategies and their relationship with environmental variables could contribute to proper fishery management.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to describe seasonal variations in the reproductive activity and gonadosomatic index of Modiolus capax in two beds located at different depths in Ensenada de La Paz, B.C.S., as well as the relationship of these variables with temperature and food availability (using chlorophyll-a as an indicator).

Materials and methods

Specimens were collected at Ensenada de La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico, (24.18-240.1 N, -110.31 - 110.41 W), from two beds (A: 24.1725 N, -110.3108 W and B: 24.149283 N, -110.339 W) (Fig. 1). Bed A is a natural bed of M. capax in the intertidal zone, in a sandy substrate, with dead coral and sandstones, at a maximum depth of one meter. Bed B comprises an artificial reef created in 1974 on a ship sunk to a depth of five meters (deep surface), serving as substrate for a mussel bed of M. capax.

Figure 1 Map of Ensenada de La Paz, Gulf of California, Mexico, indicating the locations of mussel sampling sites. Locality A: Intertidal, maximum depth of one meter; Locality B: Deep surface bed, at five meters deep.

In each locality, water temperature was recorded each month (with a mercury glass thermometer); monthly chlorophyll-a data were used as an indicator of primary productivity, from October 2008 to December 2010; chlorophyll-a concentration in La Paz Bay (24.5 N, 111.5 W) was obtained through the data server “Environmental Research Division’s Data Access Program” of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Twenty-five (± 4.5) specimens were collected each month at Bed A from October to December 2008; February to November 2009; and January to December 2010 (except March). Also, 23 (± 4) specimens were collected per month at Bed B from October 2008 to November 2009 (except January). Mussels were collected manually with handheld spears using autonomous diving in waters up to five meters.

In the laboratory, shell length (distance between the hinge and the opening of valves), and total wet weight of somatic tissues were recorded for each individual specimen. Gonads were carefully extracted, weighed, and fixed in 10% formalin (Oyarzún et al., 2011). Afterwards, they were dehydrated through a progressive series of ethanol solutions (70 to 100%), cleared with a xylene substitute, and embedded in paraffin. Five micrometer-thick cross sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Humason, 1979). In order to identify gonadal stages within the reproductive cycle, a gonadal maturity scale was established (undifferentiated, early gametogenesis, maturing, spawning, post-spawning, and resorption) based on the criterion of Ochoa-Báez (1985).

In both beds, the relative frequency of gonad maturation stages was determined.

The gonadosomatic index (GI) is determined by the relation Pg/PS x 100, where Pg is gonad wet weight and Ps is total somatic tissue wet weight (Arrieche et al., 2002; Oyarzún et al., 2018).

The data distribution was analyzed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Lilliefords normality tests. The sex ratio was calculated, and a Chi-square test was used to explore whether differences are statistically significant (p ≤0.05). Data were transformed using the square root arcsine transformation (range between 0% and 100%) (Sokal & Rohlf, 1981). For nonparametric distribution data, a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA on ranks (p ≤0.05) was used. The establishment of the size at first sexual maturity (L50) was estimated using the logistic model to obtain the length at which 50% of the population was mature. To determine the temporal variations in the GI, means were compared between months and gonad development stages for each bed. Also, mean sizes at each gonad development stage were tested for significant differences for each bed. The correlation of maturation stages (transformed data) and gonad index (transformed data) with size and environmental variables was determined separately using Spearman’s correlation coefficient and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (version 15.0, IBM Company, U.S.).

Results

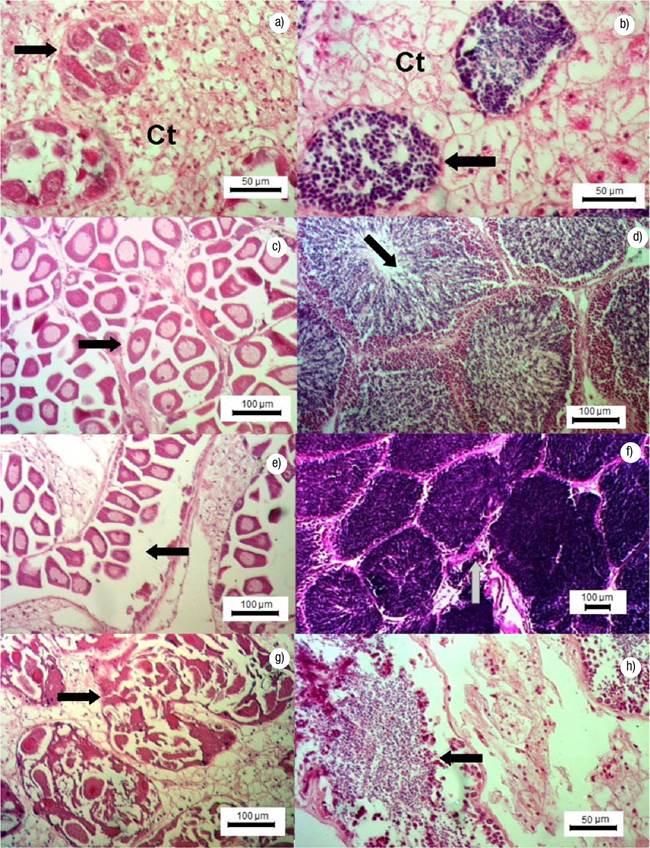

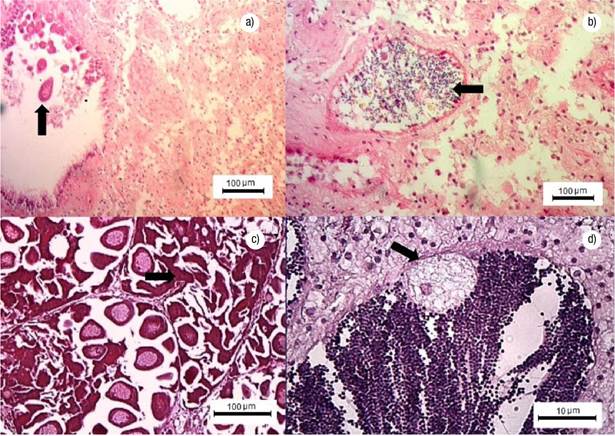

Gonadal Development Stages. Undifferentiated: germ cells are immature and connective tissue cells are scattered within a matrix; the sex of the specimen cannot be determined. Early gametogenesis: the gonad begins to develop with the appearance of small follicles in the connective tissue, containing few cells at different development stages (Figs 2a-b). Mature: the gonad is fully developed, with round follicles containing mature sex cells, occupying most of the visceral mass (Figs 2c-d). Spawning: follicles release gametes; there might be cases with clear loss of gametes (Figs 2e-f). Post-spawning: follicles contain a lower amount of mature and developing gametes relative to the previous stage. Signs of autolysis and phagocytosis are commonly observed in some areas of the gonad (Figs 2g-h). Resorption: degradation of the gonad, follicles might have residual gametes; the remaining sex cells and follicle structures are reabsorbed through phagocytosis (Figs 3a-b). A high proportion of mature gonads showed follicular atresia (autolysis) and parasites (Figs 3c-d); with 44% of parasitized males and 43% of parasitized and atretic females in intertidal (Bed A) and 22% of parasitized males and 82% of parasitized and atretic females in Bed B.

Figures 2a-h Gonadal development stages in females and males of Modiolus capax (Conrad, 1837) in La Paz, B.C.S., Mexico. a) Early gametogenesis in females, follicular development (arrow), (Ct) connective tissue; b) Early gametogenesis in males, follicular development (arrow), (Ct) connective tissue; c) Maturing in females, mature oocyte (arrow); d) Maturing in males, mature follicles (arrows); e) Spawning in females, oocyte spawning (arrow); f) Spawning in males; sperm release (arrow); g) Post-spawning in females, oocyte atresia (arrow); h) Post-spawning in male, sperm (arrow).

Figures 3a-d Stages of resorption, atretic gonad and parasitized gonad of Modiolus capax (Conrad, 1837), in La Paz, B.C.S., Mexico. a) Resorption in females, residual female gamete (arrow); b) Resorption in males, residual gametes (arrow); c) Atretic gonad, oocyte lysis (arrow); d) Male gonad, coccidian parasite (arrow).

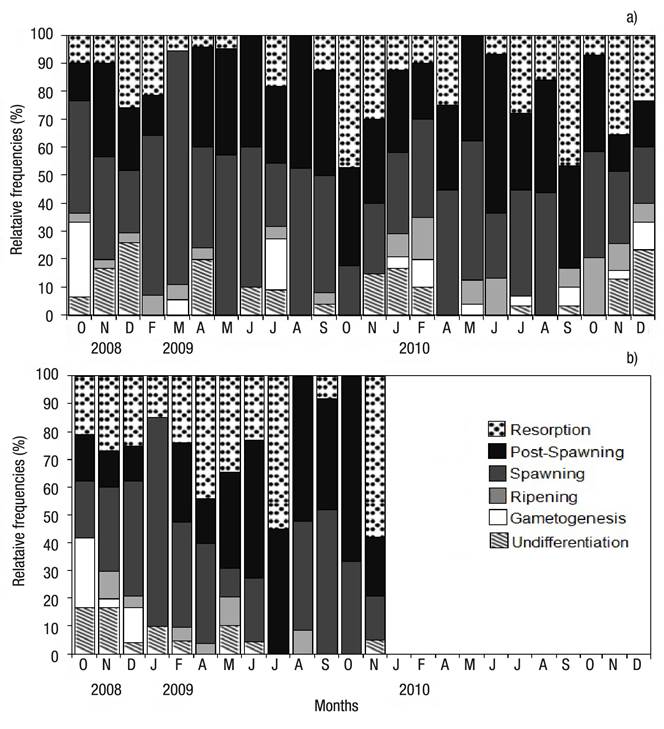

Reproductive Period. A total of 276 female, 273 male and 47 undifferentiated were examined from Bed A, and 141 female, 137 male, and 23 undifferentiated from Bed B. The sex ratio did not deviate significantly from 1:1 in both beds (Chi-square test, p >0.05). Regarding the gonad maturation pattern for the same months, differences were noted between beds. The undifferentiated stage was observed in both beds virtually throughout the whole sampling period, with peak frequency in December 2009 (25.9%, Bed A), and in October and November 2009 (16.6%, Bed B) (Figs 4a-b). Gametogenesis was rarely observed, with low percentages in both beds; peak gametogenesis occurred in October 2009 (Bed A: 26.7%; Bed B: 25%) (Figs 4a-b). Maturing was observed in low percentages in both beds; in Bed A, peak maturation was observed in February 2009 and 2010 (7% and 15%, respectively); in Bed B, peak maturation occurred in November 2008 (10%) and May 2009 (10.3%) (Figs 4a-b). Spawning prevailed throughout the whole sampling period in the intertidal-zone and deep-surface beds (Figs. 4A-B). In Bed A, spawning peaked in March 2009 and May 2010 (83.3% and 50%, respectively) (Figs 4a-b); in Bed B, peak spawning occurred in January 2009 (75%) (Figs 4a-b). In both beds, post-spawning and resorption took place throughout the sampling period; in Bed A, peak post-spawning was observed in August 2009 (47.4%) and June 2010 (56.7%); in Bed B, the maximum post-spawning occurred in October 2009 (66.7%) (Figs 4a-b). In Bed A, peak resorption was observed in October 2009 (47.1%) and September 2010 (46.7%); in Bed B, resorption was observed in November 2009 (Figs 4a-b).

Figures 4a-b Relative frequency by gonad development stage of Modiolus capax (Conrad, 1837) living in La Paz, B.C.S., Mexico, from two beds with different depth. a) Intertidal bed; (b) five meters deep bed.

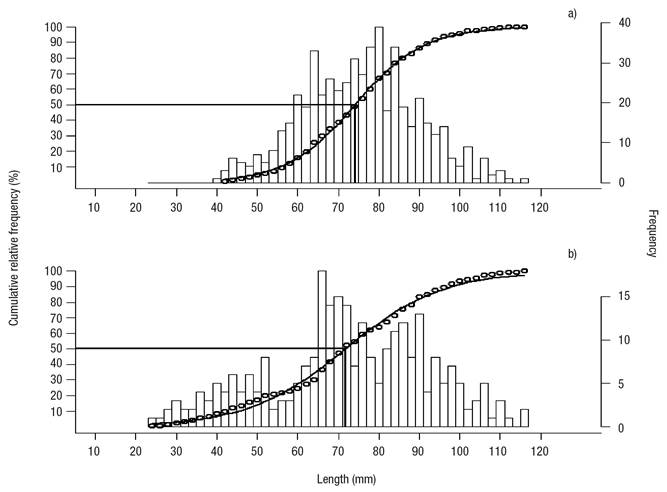

The analysis of sizes (length) showed that annual mean (2008-2009) shell length (77.8 ± 1 mm) in Bed A was significantly higher versus Bed B (72.3 ± 1 mm). The L50 estimate for Bed A (74.12 mm) was higher than for Bed B (71.74) (Figs 5a-b); also, reproductive activity started at a smaller length in Bed B (23 mm) than in Bed A (41 mm), and the mean length of the gametogenesis was lower than the other stages of gonadal maturation, 60.3 mm for Bed A and 63.4 mm for Bed B, but it was significant only in Bed A.

Figures 5a-b Size at first maturity in Modiolus capax (Conrad, 1837) living in La Paz, B.C.S., Mexico. a) Intertidal bed; (b) five meters deep bed.

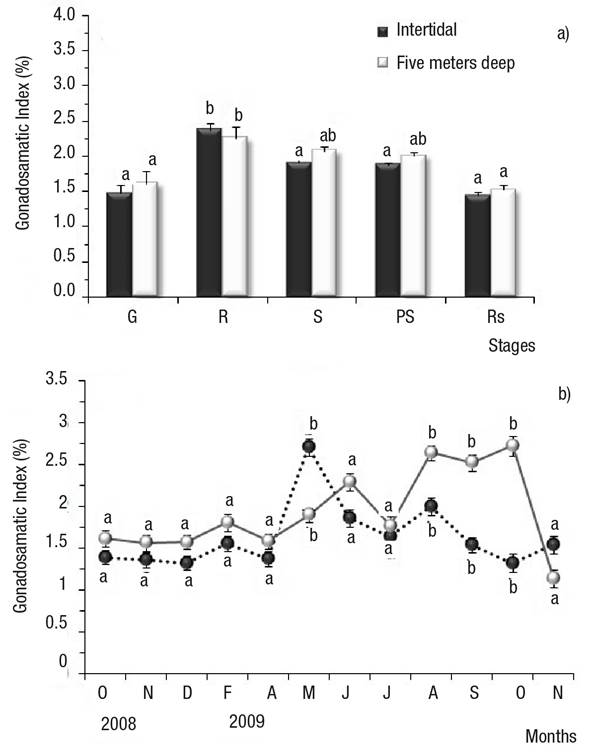

Gonadosomatic Index (GI). The GI increased from gametogenesis to mature stages in Bed A and Bed B; in Bed A, the GI in the mature stage (2.4) was significantly higher relative to gametogenesis, spawning, post-spawning, and resorption (1.5, 1.9, 1.9, and 1.4, respectively) (Fig. 6a); in Bed B, the GI in the mature stage (2.3) was significantly higher relative to gametogenesis, and resorption (1.6, and 1.5, respectively); no significant differences were observed versus spawning and post-spawning (GI = 2 , in both cases) (Fig. 6a). The GI decreased gradually from spawning to resorption, with the lowest GI values observed in the latter stage (Fig. 6a). Differences in the GI were observed between beds: in Bed A, May 2009 attained significantly higher GI values relative to Bed B; in Bed B, August, September, and October 2009 showed significantly higher GI values than in Bed A (Fig. 6b).

Figures 6a-b Mean Gonadosomatic Index (GI) of Modiolus capax (Conrad, 1837) living in La Paz, BCS, Mexico, from two beds with different depths. Values are means ± SD. (transformed data). a) Gonad development stages; b) Monthly GI by locality (transformed data). Different letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05). G: early gametogenesis, R: maturing, S; spawning, PS: post-spawning, Rs: resorption. undifferentiated, early gametogenesis, maturing, spawning, post-spawning, and resorption.

Likewise, significant differences were observed between months. In Bed A, the GI increased and showed a single annual peak, in May 2009 (8%) and June 2010 (6.6%); in Bed B, the GI increased to reach a first annual peak in June 2009 (5.7%), then started to rise again in August (7.1%), September (6.7%), and October (7.7%) (Figs 6a-b). All peaks were significantly higher than the GI of the remaining months (transformed data).

In Bed A, the GI was correlated with maturing. The GI rose in parallel with maturing frequency (arch-sine) (Bed A); Spearman’s correlation coefficient was ρ = 0.798, p <0.01.

In both beds, resorption frequency (arcsin) was negatively correlated with GI, i.e. the GI decreases as resorption frequency increases. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was ρ = -0.521 for Bed A (p <0.05), and ρ = -0.555 for Bed B (p <0.05).

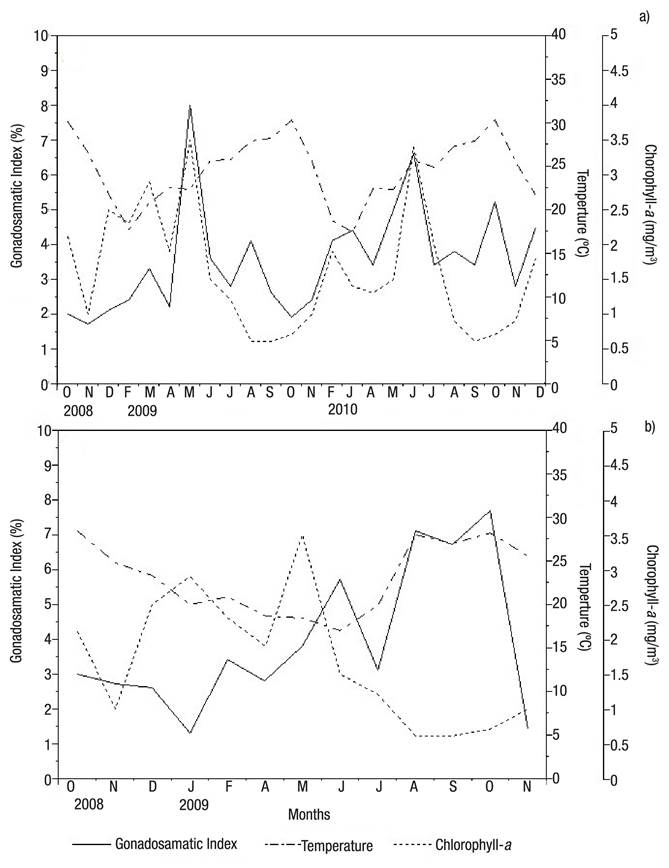

Environmental variables. Both beds recorded a drop in temperature from October to February (2008 and 2009), followed by a rise that peaked in October 2009. No significant differences were observed between beds; however, Bed A showed higher temperatures than Bed B, with maximum and minimum temperatures of 30.3 °C and 17.4 °C in Bed A, and 28.7 °C and 19.2 °C in Bed B. In both beds, maximum temperatures were recorded in October, and minimum temperatures in February (Figs 7a-b). In Bed A, maturing frequency was directly correlated with temperature, and the frequency of specimens in the maturing stage decreased with temperature from 17 °C to 30 °C; Spearman’s correlation coefficient was ρ = -0.709 (p <0.05). Peak chlorophyll values occurred in May 2009 (3.48 mg/m3) in intertidal-zone and five meters deep beds; a new increase in chlorophyll-a (3.42 mg/m3) was observed in June 2010 (Bed A). Minimum chlorophyll-a concentrations were observed in both beds in September 2009 and September 2010 (0.56 and 0.6 mg/m3, respectively) (Figs 7a-b).

Figures 7a-b Relationship of the monthly gonadosomatic index of Modiolus capax (Conrad, 1837) with temperature and chlorophyll-a concentration, from October 2008 to December 2010, in La Paz, B.C.S., Mexico. a) Intertidal bed; (b) five meters deep bed.

A relationship was observed only in Bed B between chlorophyll- a (mg/m3) and post-spawning, where the frequency of post-spawning specimens decreased as chlorophyll-a (mg/m3) increased; Spearman’s correlation coefficient was ρ = -0.555 (p <0.05).

The gonadosomatic index and chlorophyll-a increased during May and June in Bed A (2009 and 2010) (Figs 7a-b); Spearman’s correlation coefficient was ρ = 0.515 (p <0.05).

Discussion

It has been reported that the reproductive cycle of Modiolus capax produces gametes continuously throughout the year (Ochoa-Baez, 1985; Garza-Aguirre & Bückle-Ramírez, 1989a), which coincides with the results reported here. However, the peak spawning (March 2009 and May 2010 in Bed A and January 2009 in Bed B) was not consistent with the findings reported for M. capax in other studies, where peak spawning was observed in the summer (June-August), indicating gamete release increases with the rise in temperature (Ochoa-Baez, 1985; Garza-Aguirre & Bückle-Ramírez, 1989a). Likewise, this study revealed differences in the gonad maturation pattern between beds. In this regard, environmental conditions have been described as factors that determinate the reproductive behavior of bivalves, even to the extent of modifying the reproductive periodicity (Ruiz et al., 1992). Accordingly, the differences in the spawning season between beds reflects the influence of the environment on gonad activity in Modiolus capax, especially considering Ochoa-Baez’s study (1985) in the same locality, which took place during the 1983-1984 El Niño event, while Garza-Aguirre & Bückle-Ramírez’s study (1989b) was conducted in a locality where lower temperatures were reported (<15 °C) in contrast to those observed in this study.

On the other hand, the analysis of gonad development in specimens from the two beds showed a continuous gamete release almost all year, but the peak spawning recorded in March 2009 in Bed A (83%) and January 2009 in Bed B (75%) suggests a spawning synchronization in the population when the temperature was approximately 20 °C and the chlorophyll-a concentration was 2.9 mg/m3 in both beds. The above could indicate that these environmental conditions are optimal for reproduction. Spawning activity as a result of environmental changes, characterized by both scattered spawnings and a major spawning, has been described previously for M. edulis (Duinker et al. 2008). This event has also been reported in other mytilids such as Modiolus barbatus (Linnaeus, 1758) and Mytilus chilensis (Hupé, 1954), in which the asynchrony of spawning varied between localities due to environmental differences (Mladineo et al., 2007; Oyarzún et al., 2011).

Temperature and food availability have been mentioned as factors that influence the reproductive process of bivalves (Bayne, 1976). Under similar environmental conditions, differences between sexes regarding energy requirements during gonad maturation have been reported for Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1793) (Matus de la Parra et al., 2005); in this regard, laboratory studies report that in bivalve Tapes (Ruditapes) decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758), a low food intake reduces abundance of mature females but not of mature males (Delgado & Pérez-Camacho, 2005). In males of Perna perna (Linnaeus 1758), gonad development apparently takes place faster and involves less energy expenditure in males than in females (Arrieche et al., 2002). Thus, it seems clear that some males of M. capax in the population remain reproductively active most of the year, allowing a period of synchronous population spawning when females are ready to reproduce.

Another difference was the high percentage of annual post-spawning and resorption observed in both beds. In Mytilus edulis and Mytilus chilensis, it was found that a presence of post-spawning in the reproductive cycle was followed by a period of follicular resorption that prepares the organisms for a new gonad development cycle (Newell et al., 1982; Oyarzún et al., 2011). Yet, although during 2010 this behavior (onset of gametogenesis after resorption) was observed, in 2009, the maturing stage in both beds was low, and from June to November of that year there was a high percentage of post-spawning with follicular atresia, resorption, and undifferentiating stages; this period coincided with a lower chlorophyll-a concentration and a temperature rise of up to 30 °C. Thorarinsdóttir and Gunnarsson (2003) indicate that when Mytilus edulis has low carbohydrate reserves, gamete development might begin but did not reach successful gonad maturation. Newell et al. (1982) point out that variations in temperature are one of the main variables that influence spawning, while gametogenesis seems to be governed by food availability. This suggests that gamete development (to term) in M. capax depends on food availability and an optimum temperature range; otherwise, oocytes undergo follicular atresia as a result of poor viability. This was described by Newell et al. (1982) for various populations of Mytilus edulis. On the other hand, Suárez-Alonso et al. (2007) indicate that when nutrients are scarce and under adverse temperature conditions, females of Mytilus galloprovincialis (Lamarck, 1819) show follicular atresia followed by gamete resorption as a strategy to recycle energy reserves for subsequent gonad maturation when conditions become favorable. The high GI value in post-spawning specimens was probably due to the large number of atretic follicles in post-spawning specimens (up to 82%). Ángel-Pérez et al. (2007) mentions that gonadal atresia is common in species in which gametogenesis is controlled by environmental conditions. In this regard, Fearman et al. (2009) report that M. edulis is unable to complete gonad maturation when the temperature rises and there is food scarcity. In particular, M. capax has been reported as a species with a low retention of mature gametes, which are reabsorbed when they are not released (Farfán & Espinoza-Peralta, 1998). This implies that resorption responds not only to environmental conditions, but also to the genetics of this specie. Additionally, although follicular atresia tends to be driven by environmental events, such as food scarcity and unfavorable temperatures, in this study we observed a high abundance of parasites in gonads, which might have also affected follicular atresia. In mussels, the reproductive status is known to be affected not only by environmental variables but also by diseases (Bignell et al., 2008).

The gonadosomatic index (both beds) observed in each gonadal development stage revealed a steady growth of the gonad during gametogenesis, with maximum growth during the maturing stage, followed by progressive reduction in gonad size, which is most noticeable during resorption; this finding coincides with the one reported by Garza-Aguirre and Bückle-Ramírez (1989a) for M. capax, i.e., the GI increases with gonad maturing.

The mean size (shell height and length) associated with the gonadal development stages in both beds evidenced that organisms in the early gametogenesis stage were of small size (less than 70 mm). It was also noted that mussels larger than 71.6 mm in length are capable of spawning. Although the average length of specimens showing early gametogenesis in both locations was the smallest, we are not sure if these smaller mussels had completed the maturation process. In this regard, Rodhouse et al. (1986) notes that M. edulis increases in body size (height and weight) during the first 3 years of life, and afterwards an increase in gonad maturation is observed. For this same species, Delmott and Edds (2014) reported in the zebra mussel Dreissena polymorpha (Pallas, 1771) that onset of gametogenesis might vary according to the locality, although this did not occur in mussels smaller than 5 cm in shell length, as these were very young. The above suggests that in general, the specimens showing early gametogenesis analyzed in this study were young mussels that were undergoing gonad development for the first time. Ochoa-Báez (1985) mentions that the recruitment of mature M. capax occurs at 30 mm to 40 mm in length, with peak reproductive performance between 60 mm and 100 mm in length (+2 years old), at a mean temperature of 32 °C. Garza-Aguirre and Bückle-Ramírez (1989a) report that in M. capax beds living in the intertidal zone, no gametogenic activity was observed in mussels under 43 mm in length, and that gametogenesis is delayed at temperatures between 15 °C and 25 ºC, and progresses at a faster rate at temperatures higher than 26 °C. Based on the above, we can infer that in M. capax, the size at the onset of gonad maturation, as well as the reproductive periodicity, will differ between localities, largely depending on environmental variables (such as temperature and food availability), which are modified by habitat and depth. This was confirmed by the differences in sizes found between the intertidal site and at the five meters deep. This influence of environmental characteristics on growth and the gonad development response (different reproductive peaks) in M. capax provide evidence that reproductive capacity and its timing may differ in each locality. For this reason, we recommend the development of specific management strategies for each bed as a precautionary measure to preserve resource sustainability.

In addition, knowing the temperature ranges within which this species achieves maturation is important in aquaculture, e.g. in the production of seed and the definition of culture areas, thus avoiding conditions that promote the onset of gonad maturation at small sizes. In other mollusks, it has been reported that early reproduction leads to a lower growth rate, due to the higher demand of metabolic energy for gonad development (Kanazawa & Sato, 2008).

This study shows that, in spite of the continuous reproductive activity in Modiolus capax, there are differences in gonad development between beds, which result in a narrow reproductive peak that varies between the beds, possibly triggered by environmental conditions (temperature and food availability) that are optimum for the reproduction of M. capax. Similarly, we observed that environmental variables influence the size at onset of gametogenesis and maturity, as well as the interruption of the reproductive process (evidenced by high follicular atresia).

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)