Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicación y sociedad

Print version ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.17 Guadalajara 2020 Epub Jan 27, 2021

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2020.7284

General theme

Television audience measurement: the challenge posed by video streaming platforms

1 Universidade da Coruña, Spain. ana.gneira@udc.es

2 Universidade da Coruña, Spain. n.quintas.froufe@udc.es

3 Universidad Camilo José Cela, Spain. jgallardo@ucjc.edu

This article analyses the different television audience measurement (TAM) systems used in European countries and reflects on the challenges posed by the arrival of new competitors, such as over-the-top (OTT) service providers, in the current media landscape. The results show that although TAM companies are trying to adapt to these changes, their systems and methods still ignore important new players like Netflix and are yet to reflect the audiovisual content consumption habits of today’s audiences.

Keywords: Audience; audience measurement; OTT; television; video streaming platforms

Tras estudiar los sistemas de medición de la audiencia televisiva en diferentes países, se reflexiona sobre los desafíos de la audimetría en el escenario mediático actual ante la llegada de nuevos competidores como las OTT. Los resultados demuestran que se está haciendo un esfuerzo por adaptarse a esos cambios, pero la audimetría aún no refleja el consumo real al dejar al margen a nuevos e importantes actores como Netflix.

Palabras clave: Audiencia; audimetría; televisión; plataformas de streaming de video; OTT

Introduction

The current media ecosystem has imposed changes on the operating dynamics of traditional media platforms and has even modified some of their most characteristic features. Television, for instance, has been forced to adapt to the new reality of the audiovisual landscape, which has been disrupted by the emergence of new media content providers, such as Netflix and other over-the-top (OTT) media services, and new forms of mobile media consumption that do not follow traditional broadcasting schedules. These changes have given rise to what we have called “liquid television” (Quintas-Froufe & González-Neira, 2016), using Bauman’s words (2006).

The rapid penetration into the international audiovisual market of OTT operators and their innovative business models have revolutionized the sector and transformed the audiovisual content consumption habits of the audience. The new forms of consumption they enable have led to the emergence of other audience types, such as the social audience (Claes & Deltell, 2015; Deller, 2011; Deltell Escolar, Claes & Congosto Martínez, 2015; Giglietto & Selva, 2014; Lin, Sung & Chen, 2016; Miranda & Fernández, 2015; Quintas-Froufe & González-Neira, 2014) and the time-shifted audience (Gallardo-Camacho & Sánchez-Sierra, 2017; González-Neira & Quintas-Froufe, 2016). Despite the obvious differences between the two audience types, they coexist in a hyperconnected environment with excellent technological conditions that provide ubiquitous connection and constant access to social networks (Quintas-Froufe & González-Neira, 2016).

The digitization of television and audience’s growing access and use of new technologies have given rise to what some authors such as Cerezo and Cerezo (2017) call “a new television paradigm”. As Papí and Perlado (2018) point out, in this new paradigm the mutation of the communication model shows that traditional audience measurement systems do not capture the complexity of today’s digital environment. Audience measurement research constantly seeks to improve the accuracy of measurement systems to provide media, advertisers and advertising agencies with data and assurances about the effectiveness of their campaigns as well as an accurate segmentation of their target audience.

In this media scenario, traditional television audience measurement (TAM) methods are being questioned by the industry itself. Already in 2003, Carlos Lamas (Executive Director of the Media Research Association) highlighted some of the aspects of audience measurement that should be reconsidered in the near future (sample size, people meters, digital television measurement, etc.). Years later, in 2011, Fernando Santiago (former Technical Director of the Media Research Association) pointed out the main challenges of audience measurement, including the need for new cross-platform measuring systems (TV + PC + mobile devices).4 Currently, the Spanish industry continues to demand the definitive application of comprehensive cross-media audience measurement to be able to measure viewing from each of the different devices used by the audience, which is one of the immediate challenges of audience measurement systems.

In the academic field, the most current advances in TAM in the age of Big Data have been documented by several authors, such as Athique (2018), Kelly (2017), Kosterich and Napoli (2016), Nelson and Webster (2016) and Hill (2014). However, research on audience measurement is not a very prolific area. In this regard, it is worth noting the contributions made by Bourdon and Méadel (2011, 2014, 2015), Buzeta and Moyano (2013), Buzzard (2012), Huertas-Bailén (1998, 2002), Jasuet (2000), Madinaveitia and Merchante (2015), Medina and Portilla (2016), Napoli (2014, 2011), Nightingale (2011), Papí and Perlado (2018), Portilla (2015), Blumler (1996), Webster, Phalen and Lichty (2005), who provide the theoretical framework for the development of this research.

In short, media consumption, mainly audiovisual, in different mobile devices has highlighted the urgent need for the ATAWAD (anytime, anywhere, any device) measurement of each user, as Hernández-Pérez and Rodríguez (2016) have pointed out. This research, therefore, aims to describe how TAM is currently carried out at the international level to determine whether it is adapted to this new context and whether it takes into account new forms of audiovisual consumption.

Within this context, the first objective of this article is to study the TAM systems used in different European countries, focusing on the Spanish case.5 The aim is to identify the indicators, systems and technologies used by multinational TAM companies operating in a sample of European countries, to carry out a comparative analysis from an international perspective. This study will allow us to conclude whether there are differences in the metrics used by large multinational TAM companies and whether such metrics can affect the overall results.

The second objective is to reflect on the challenges of TAM in the current media scenario in the face of the arrival of new competitors such as OTT players. Netflix is the selected OTT platform due to its leadership in its domestic market (the United States of America), its international expansion (Izquierdo-Castillo, 2015) and its rapid penetration in Spain, where it has become the streaming platform with the largest growth during the analysis period, reaching the second position in less than a year (Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y de la Competencia [CNMC], 2017). This objective involves the identification of the main difficulties to collect data from new audiences and their time-shifted and multidevice consumption.

Methods

To achieve the first objective, the selection of television as the object of study is justified by the fact that it is the most consumed medium in the world (Cerezo & Cerezo, 2017). To this end, the analysis takes into account the methods used in the European countries belonging to the European Media Research Organization (EMRO), a Swiss-registered, non-profit association that aims to promote contact and discussion of individuals working in organizations engaged in audience measurement at a national level for any medium or combination of media (European Media Research Organisation-EMRO, 2018). EMRO members are divided into three types: JIC (Joint Industry Committee):6 organizations controlled completely the market; MOC (Media Owner Committee):7 organizations controlled by a share of the market; and research institutes,8 all of them from 21 countries: Austria, Germany, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, Greece, Morocco, Norway, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, United Kingdom, Czech Republic, Romania, Russia, Sweden, Switzerland and Ukraine.

Annually, since 2015, EMRO publishes its Audience Survey Inventory (EASI), which collects the most relevant data on the media audience research carried out in the member countries. This source is key to know the state of audience research from an international perspective and to reflect on the challenges of digital audience measurement (Papí & Perlado, 2018). This study takes as a reference the 2018 version of the Audience Survey Inventory (EMRO, 2018), which provides data from 19 countries (Austria, Germany, Belgium, Bulgaria, Spain, Finland, the Netherlands, Greece, Morocco,9 Norway, Poland, Portugal, Czech Republic, Romania, United Kingdom, Russia, Sweden, Switzerland and Ukraine). Alongside the information provided in the EASI, special emphasis will be placed on how different States have tried to address the measurement of audiovisual viewing across mobile devices. The study relies on a descriptive, mixed methods approach.

For the fulfillment of the second objective, and in the absence of literature and reports on the weight of the Netflix in the Spanish audiovisual audience, five semi-structured in-depth interviews have been conducted with the heads of the audience departments of the three major audiovisual television groups in Spain (RTVE, the Spanish Radio and Television Corporation, and Atresmedia and Mediaset Spain, two private networks); the head of the southern Europe division of Kantar Media, the dominant TAM in Spain; and the head of audiences of the audiovisual analysis agency Dos30’. Table 1 shows the positions and names of the people interviewed between April 25th and May 5th, 2018, who form a panel of experts relevant to our research topic in Spain.

Table 1 Panel of experts from television networks, TAM companies and audiovisual consultants

| Name | Company | Charge | Interview date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ignacio Gómez | RTVE | Head of Analysis and New Projects | 04/05/2018 |

| Javier López Cuenllas | Mediaset Spain | Head of Marketing | 26/04/2018 |

| Santiago Gómez Amigo | Atresmedia Television | Head of Marketing | 30/04/2018 |

| Miguel Ángel Fontán | Kantar Media | Regional Director in Southern Europe | 15/04/2018 |

| Chema García Ruiz | Dos30’ | Audience Director | 05/05/2018 |

Source: The authors.

Television audience measurement in Europe

Based on the data provided by EMRO (2018), the research focused on analyzing which companies are responsible for TAM, the types of companies they are, they variables they measure, the way they do it, and the types of reports they issue.

Table 2 presents the number of companies responsible for measuring the viewership of television content broadcast on both public and private channels.

Table 2 Number of monitored channels per country

| Countries | Number of channels | Countries | Number of channels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Not available | Poland | 178 |

| Austria | 14 | Portugal | 163 |

| Belgium | 70 | United Kingdom | 291 |

| Bulgaria | 63 | Romania | 59 |

| Finland | 95 | Russia | 407 |

| Spain | 123 | Czech Republic | 42 |

| Greece | 52 | Sweden | 126 |

| Holland | 112 | Switzerland | 361 |

| Norway | Not available | Ukraine | 52 |

Source: EMRO (2018).

These companies measure the audience of public and private, regional, national, international and foreign television networks. Russia and Switzerland monitor more than three hundred channels, followed closely by the UK. However, new players such as Netflix and Amazon Prime Video are not considered in these measurements.

The research reveals that a significant majority of companies (10) belong to the JIC category. After this modality, there are six countries where TAM is performed by research institutes. Meanwhile, MOC’S companies only operate in Austria and Norway. As in the rest of the world, the latter type constitutes the minority. Therefore, the dominant category is the one in which measurement companies belong to different types of organizations related to the communication process (such as advertisers, advertising agencies and the media) and have considerable interests in knowing the results of this type of measurement.

In the analyzed countries, all the companies responsible for audience measurement are in the hands of big multinationals: Kantar Media, Nielsen and GfK. Through different structures and business models, these multinationals have absorbed local companies in recent years through different business strategies. Therefore, it can be concluded that the concentration trend that started a few years ago in the TAM sector has become consolidated.

Having analyzed audience measurement as a business sector, it is necessary to examine the way it works. In order to know the representativeness of the measurements performed, we need to examine the panels of the different countries. The largest panels correspond to Russia (5 400 households), the United Kingdom (5 100 households) and Germany (5 000 households), which are also the countries in the sample with the largest populations. The fourth place is occupied by Spain, with 4 625 households monitored.10 However, it is necessary to study the degree of representativeness of these panels to analyze their accuracy. To this end, we measured the relationship between people meters and the number of households in each country, and the data on the population and the sample of individuals analyzed. In this way, the proportion and therefore the representativeness of the measurements are established in more detail.

Table 3 Representativeness of measurements by households and individuals

| Countries | Household representation | Individual representation |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 1/ 2 312 | 1/ 2 305 |

| Germany | 1/ 7 638 | 1/ 7 150 |

| Belgium | 1/ 2 979 | 1/ 2 779 |

| Bulgaria | 1/ 2 348* | 1/ 2 206 |

| Spain | 1/ 3 968 | 1/ 3 971 |

| Finland | 1/ 2 367 | 1/ 2 385 |

| Holland | 1/ 6 072 | 1/ 5 626 |

| Greece | No data | 1/ 2 967 |

| Norway | No data | 1/ 2 093 |

| Poland | 1/ 6 806 | 1/ 6 569 |

| Portugal | 1/ 3 517 | SD |

| Czech Republic | 1/ 2 313 | 1/ 2 278 |

| Romania | 1/ 5 759 | 1/ 3 971 |

| United Kingdom | 1/ 5 098 | 1/ 5 043 |

| Russia | 1/ 5 083 | 1/ 5 086 |

| Sweden | 1/ 3 750 | 1/ 3 579 |

| Switzerland | 1/ 1 797 | 1/ 1 673 |

| Ukraine | 1/ 4 754 | 1/ 4 856 |

Given the absence of data about Bulgaria, Norway, and the Czech Republic in the EASI, TAM companies operating in these countries were consulted to complete this analysis.

Source: EMRO (2018).

The extracted data show that the countries whose panels are larger do not have the highest representativeness. This confirms that there is a certain correspondence between countries whose household and individual universes are smaller and those with greater representativeness. This situation is led by Switzerland, followed by Norway, Austria and the Czech Republic. In the opposite extreme is Germany, which quadruples the representativeness of Switzerland, followed by Poland and the Netherlands. In this case, there is no correspondence between the number of households monitored and the general universe of each country as demonstrated by the Spanish case, with a ratio of one meter per 3 968 households and one meter for every 3 971 individuals.

With regards to the measurement system, the results show that each multinational company often has its own trusted meter, which is distributed across different countries. For example, GfK uses Telecontrol in Austria and Germany; Kantar uses Taris 5000 in Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands and United Kingdom; while Nielsen generally uses Unitam in Ukraine, Sweden and Poland.

With regards to measurement technology, all countries use audiomatching.11 However, some of them do not use it exclusively, and combine it with Teletext code (like Austria, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands) and Watermarking12 (like Norway, Holland and Great Britain).

With regards to the object of measurement, it is interesting to determine the extent to what it has been adapted in these countries to the changes experienced in the television industry. In other words, it is important to know whether these measurements include the new viewing modalities that have been introduced in recent years.

In this regard, the report responds in two directions. On the one hand, it indicates that the increase in time-shifted viewing of some contents has forced the inclusion of questions that contemplate this new modality, already addressed by Castells (2009). The research indicates that most of these countries have introduced the VOSDAL (Viewed on Same Day as Live) metric, with the exception of Greece and Switzerland. Most countries have also added viewing 7 days after broadcast, except for Greece, Russia, the Czech Republic and Germany (the latter country collects viewing data 3 days after broadcast). However, in relation to the so-called long-term time-shifted viewing, data are more negative. Only Norway and the United Kingdom collect data on time-shifted viewing within 28 days after broadcast.

A second important issue concerns the possibility of collecting data from streaming on devices other than television such as desktop computers and laptops, tablets and smartphones. Recent studies confirm that different countries have incorporated the monitoring of this type of viewing in other devices. In this sense, the Czech Republic, Finland, Russia, Sweden, Austria and Switzerland collect viewing data on computers, while Austria, Czech Republic and Finland collect data on viewing on tablets and smartphones.

In relation to the products these companies offer, all reports and data are paid for. In all the countries under study, television networks pay for access to all available information, unlike advertisers. In addition, except for Belgium, Poland, Romania, Sweden, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, in the rest of the countries, television broadcasters have access to custom-made reports.

The importance of measuring the Netflix’s audience in the Spanish market

As reflected in the previous section, in Spain, Kantar Media measures three types of audiences: the linear audience (which takes into account the consumption of what is seen on the main television set of each household); the time-shifted audience (which registers, since February 2015, the consumption of television programs one minute after their linear broadcast and up to seven days after broadcast, and only on the main TV set); and the social audience (which measures and quantifies, since December 2014, the conversations and interactions generated by a TV show on Twitter). The measurement of the linear and time-shifted audience is performed through 4 755 people meters spread across the country (Eurodata, 2018). However, Kantar Media ignores certain broadcasters that have emerged in recent years and does not quantify the weight of Netflix and other streaming companies (the so-called OTT services) with respect to traditional television. That is why it is difficult to determine the real weight of Netflix in Spain and in the rest of the world, because there is no measurement method that establishes the audiovisual weight of this platform.

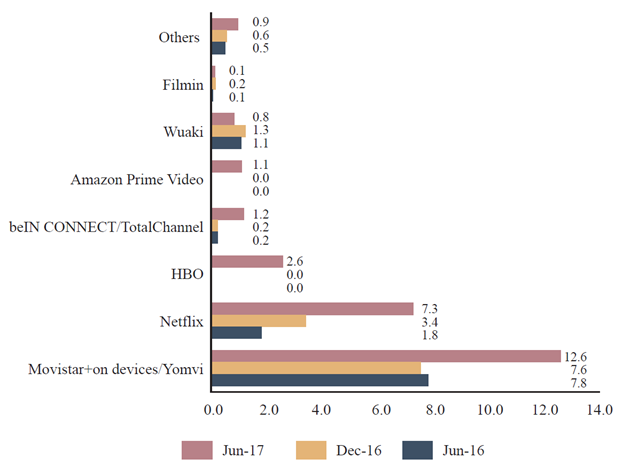

Netflix arrived in Spain in October 2015, but it does not share subscriber data. The National Commission on Markets and Competition (CNMC, 2017) is the only entity that measures the penetration of online payment platforms in the audiovisual market (Figure 1).

Source: The authors, based on CNMC data (2017).

Figure 1 Use of video streaming platforms (percentage of households)

Figure 1 shows that Netflix is the video streaming platform that has grown the most during the analysis period, as it doubled in six months its number of users to reach 7.3% of the Internet population: 1 163 000 households in June 2017 with this service, compared to 550 000 in December 2016. On the other hand, Movistar+,13 the payment TV platform, in Spain, also offers its services online and conquered the Spanish market, with 12.6%. HBO entered the market in 2017 with 2.6%, which represents 414 000 households. It is important to clarify that 0% refer to periods when data were not available because HBO and Amazon Prime Video services were not available in Spain. The CNMC household panel also reflects the rapid increase of payment video streaming platforms: almost one in every four households with Internet access is subscribed to one of the streaming services. In fact, the percentage of people who claim not to use such platforms has drop rapidly, from 89.3% in June 2016 to 77.5% in June 2017, according to the same household panel prepared through a survey applied during the second quarter of 2017 to 8 839 individuals in 4 937 households.

The data shows that the Netflix phenomenon has burst rapidly in the Spanish audiovisual market, reaching 1 163 000 households. However, it is not clear how this volume of subscribers affects traditional television. Kantar Media measures the traditional television audience through people meters and calculates the total number of individuals, aged 4 years and older, who are watching television in a fixed time period. For example, 2017 closed with the following data related to traditional television (Barlovento Communication, 2017): of the 44.6 million potential viewers as a universe of consumers, 1 054 000 people did not watch television in December. Moreover, 72.1% of Spaniards, or 32 172 000 individuals, watched television in a daily basis. In the cumulative monthly data, 97.6% of the population aged 4 and over had watched at least one minute of television content in the last month. These data indicate that traditional television maintains an undisputed leadership, but also reflect the difficulty of quantifying the effects of on-demand streaming platforms, such as Netflix, on the traditional audience. Hence, the importance of asking the experts in the daily measurement of the Spanish audiovisual audience. Table 4 shows the responses of the expert panel regarding the weight of video streaming platforms.

Table 4 Questions related to the weight of video streaming platforms

| Interviewee | Do they decrease traditional TV consumption? | Should they be measured as traditional TV? | Strategy to compete against OTT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ignacio Gómez (RTVE) | Yes. “The fall in consumption is not only due to OTT platforms”. | Hardly. “Netflix and HBO business models are based on subscription, not advertising”. | - Production of quality content. - Improvement of on-demand consumption interfaces. |

| Javier López Cuenllas (Mediaset Spain) | Yes. “Drops in consumption are not just due to Netflix and other OTT’s”. | “Netflix is not TV and cannot become part of the audience measurement”. | - Plenty of live content. - Eye-catching and entertaining products. |

| Santiago Gómez Amigo (Atresmedia Television) | Yes. “Especially among young people and to a lesser extent in central audiences”. | Yes. “It would be good for the market if it were measured”. | - Exclusive content. - Live broadcast. |

| Miguel Ángel Fontán (Kantar Media) | Yes. “There are no accurate measurements, but this new model of video consumption is becoming part of the market”. | No. “They are like a great online video store and in the golden age of video and dvd no one considered it was TV consumption”. | - Produce compelling and live content. - Development of their own on-demand content platforms. |

| Chema García Ruiz (Dos30’) | Yes. “TV consumption in Spain has dropped 14 minutes per viewer per day since the arrival of Netflix”. | Difficult. “These are other ways to consume TV that add up minutes but are isolated from the traditional network approach”. | - Boost online content platforms. |

Source: The authors.

It also shows that the whole panel agrees that the new platforms have subtracted consumption from traditional television among the youth audience, although they also clarify that the decline in consumption is not only due to this phenomenon. For example, Javier López Cuenllas (Mediaset Spain) warns us that “we now diversify our leisure in many places: a social network, a messaging service, an entertainment device, etc.”. For his part, Miguel Ángel Fontán (Kantar Media), the person responsible for TAM in Spain, adds that “television remains the dominant medium, with an enormous difference, and enjoys good health”.

Traditional television has also started to produce on-demand online content like Netflix and similar platforms. If this audience is measured, why not try to relate it to the one generated by the other platforms? The debate opens when it comes to raising the need to measure the weight of Netflix and the rest of OTT platforms to compare their consumption with that of traditional television. It is difficult to simplify the answers of the interviewees to a yes or no because all of them have nuances. For example, the Atresmedia Audience Director is the only expert who shows an interest in measuring streaming consumption, although he believes that it should be done “separately from live TV” and that it would be similar to the current measurement of time-shifted consumption “to know how many people watches live TV and at what times”. The expert from Mediaset strongly believes that Netflix is not television and that its audience should not be measure, although he accepts that they should be able to compare broadcast and streaming consumption. Ignacio Gómez (RTVE) adds that it would be good to improve the way online audiovisual consumption is measured and that they “are working on cross media measurement with Kantar Media and Comscore”. For his part, Fontán (Kantar Media) does not believe that the online audience should be measured comparatively with television, although “this does not mean that it is not interesting and almost necessary to be able to measure it”. Consultant Chema García Ruiz (Dos30’) acknowledges that this debate “is unclear and that the industry itself must set the rules”.

As for the strategy to compete against online video platforms, the people responsible for the three television groups in Spain (RTVE, Mediaset and Atresmedia) and the rest of interviewees agree that the creation of quality, exclusive, innovative and, above all, live content is the answer. However, in addition to content, there is also a clear need to continue improving the online platforms of TV networks to achieve a user experience like the one provided by OTT platforms such as Netflix.

Conclusions

Based on the analysis of TAM systems, this research reveals that while audience measurement in Europe has attempted to adapt to new forms of consumption through other devices (tablets or smartphones) or time-shifted viewing, it has not yet been able to take a complete picture of the television landscape. Audience measurement does not take into account the new television players like OTT video services, leaving out a significant part of consumption,14 which is one of the immediate challenges for the measurement of the television and audiovisual audiences. It is essential for audience research to also adapt to this new context in a way that is able to provide accurate data about this reality and takes into account the new forms of cross-platform consumption.

There is also a certain degree of concentration of audience measurement systems in the hands of three multinational companies that have been buying local companies. In an incrEASIngly international context of consumption and content, it is desirable to homogenize audience measurement tools, methods and formats across countries to be able to compare data accurately and EASIly. The integration of metrics would imply prior agreement among all actors involved in the audiovisual sector to determine and select the adequacy of methods and indicators, which would require a debate to address multiple issues. Therefore, considering the fact that three companies control TAM in Europe, the disparity of criteria to measure time-shifted viewing and streaming on devices other than the television in the living room does not make sense. For example, in the Spanish case we conclude that these differences are due to the fact that audience measurement is funded by TV networks and that an increase in the accuracy of the results obtained from the panels in each country depends on their budget allocations. That is, if TV networks paid more to TAM companies, they could demand greater accuracy in the analysis of new audiences to be able to respond to market demands. This would explain why the UK measures time-shifted viewing up to 28 days after linear broadcasting, compared to the 7 days measured in Spain. However, traditional television networks have a decisive power over which variables can or cannot be considered in audience measurement, as they fund these studies. It is precisely this power that gives them the possibility to veto the measurement of other operators like Netflix, which are subtracting minutes from television consumption.

Based on the opinions of the panel of experts (Table 1), it is concluded that the consumption of television has fallen in Spain, among other reasons, due to the incrEASIng use of OTT video platforms, such as Netflix, mainly among viewers under the age of 30. The interviewed experts also highlight the need to improve audience measurement systems to quantify the importance of consumption of online video platforms. However, there is no consensus on whether such data could be compared with traditional television data, as there is a debate on the definition of television. While OTT video platforms look for subscribers, television companies need to quantify their impact to attract advertisers, at least, in their linear broadcast project. The incrEASIng time-shifted consumption of the content generated by television networks could change this measurement system in the medium term, although live broadcasts will be the life insurance of traditional linear television.

On the other hand, it is also concluded that the penetration of the new video streaming platforms is very fast since, for example, Netflix managed to enter 1 163 000 Spanish households in just three years since its arrival in the country. This can make audience measurement systems in Spain and other markets change sooner than we think.

In short, the current state of audience measurement does not reflect the actual consumption of television content as it ignores new and important players. Undoubtedly, future research works will have to address the transformations that audience measurement multinational companies will have to undertake.

REFERENCES

Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación-AIMC. (2011). Panorama internacional frente a los retos de la audimetría actual (AEDEMO-Febrero 2011). https://www.aimc.es/blog/panorama-internacional-frente-a/ [ Links ]

Athique, A. (2018). The dynamics and potentials of big data for audience research. Media, Culture & Society, 40(1), 59-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717693681 [ Links ]

Barlovento Comunicación. (2017). Audiencias en diciembre de 2017. https://www.barloventocomunicacion.es/blog/180-analisis-de-audiencias-TV-diciembre-2017.html [ Links ]

Bauman, Z. (2006). Modernidad líquida. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Blumler, J. G. (1996). Recasting the audience in the new television marketplace. En J. Hay, L. Grossberg & E. Wartella (Eds.), The audience and its landscape (pp. 97-112). Westview Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429496813-9 [ Links ]

Bourdon, J. & Méadel, C. (2011). Inside television audience measurement. Media, Culture and Society, 33(5), 791-800. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443711404739 [ Links ]

Bourdon, J. & Méadel, C. (Ed.) (2014). Television audiences across the world. Deconstructing the ratings machine. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443711404739 [ Links ]

Bourdon, J. & Méadel, C. (2015). Ratings as Politics. Television Audience Measurement the State: An International Comparison. International Journal of Communication, 9, 2243-2262. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3342/1427 [ Links ]

Buzeta, C. & Moyano, P. (2013). La medición de las audiencias de televisión en la era digital. Cuadernos.info, 33, 53-62. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.33.503 [ Links ]

Buzzard, K. (2012). Tracking the audience. The ratings industry from analog to digital. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203149492 [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2009). Comunicación y poder. Alianza. [ Links ]

Cerezo, J. & Cerezo, P. (2017). La televisión que viene [dossier]. http://evocaimagen.com/la-tv-que-viene-nuevo-dosier-evoca/ [ Links ]

Claes, F. & Deltell, L. (2015). Audiencia social en Twitter: hacia un nuevo modelo de consumo televisivo. Trípodos, 36, 111-132. http://www.tripodos.com/index.php/Facultat_Comunicacio_Blanquerna/article/ view/245 [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y de la Competencia-CNMC. (s.f.). Estadísticas del Panel de Hogares 2017. http://data.cnmc.es/datagraph/ [ Links ]

Deller, R. (2011). Twittering on: Audience research and participation using Twitter. Participations, 8(1), 216-245. http://www.participations.org/Volume%208/Issue%201/pdf/deller.pdf [ Links ]

Deltell Escolar, L., Claes, F. & Congosto Martínez, M. L. (2015). Enjambre y urdimbre en Twitter: análisis de la audiencia social de los premios Goya 2015. En N. Quintas Froufe & A. González Neira (Coords.), La participación de la audiencia en la televisión: de la audiencia activa a la social (pp. 60-82). Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación (AIMC). [ Links ]

European Media Research Organisation-EMRO. (2018). EMRO Audience Survey Inventory (EASI) 2018. https://www.emro.org/easi/easi2018.html [ Links ]

Gallardo-Camacho, J. & Sierra Sánchez, J. (2017). La importancia de la audiencia en diferido en el reparto del poder entre las cadenas generalistas y temáticas en España. Revista Prisma Social, 18, 172-191. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/1381 [ Links ]

Giglietto, F. & Selva, D. (2014). Second Screen and Participation: A Content Analysis on a Full Season Dataset of Tweets. Journal of Communication, 64(2), 260-277. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12085 [ Links ]

González-Neira, A. & Quintas-Froufe, N. (2016). El comportamiento de la audiencia lineal, social y en diferido de las series de ficción española. Revista de la Asociación Española de Investigación de la Comunicación, 3(6), 27-33. http://www.revistaeic.eu/index.php/raeic/article/view/63 [ Links ]

Hernández-Pérez, T. & Rodríguez, D. (2016). Medición integral de las audiencias: sobre los cambios en el consumo de información y la necesidad de nuevas métricas en medios digitales. Hipertext.net, 14, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.2436/20.8050.01.32 [ Links ]

Hill, S. (2014). TV audience measurement with big data. Big data, 2(2), 76-86. https://doi.org/10.1089/big.2014.0012 [ Links ]

Huertas-Bailén, A. (1998). Cómo se miden las audiencias de televisión. CIMS. [ Links ]

Huertas-Bailén, A. (2002). La audiencia investigada. Gedisa. [ Links ]

Izquierdo Castillo, J. (2015). El nuevo negocio mediático liderado por Netflix: estudio del modelo y proyección en el mercado español. El profesional de la información, 24(6), 819-826. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2015.nov.14 [ Links ]

Jasuet, J. (2000). La investigación de audiencias en televisión: fundamentos estadísticos. Paidós. [ Links ]

Kelly, J. P. (2017). Television by the numbers: The challenges of audience measurement in the age of Big Data. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 25(1), 113-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517700854 [ Links ]

Kosterich, A. & Napoli, P. M. (2016). Reconfiguring the Audience Commodity: The Institutionalization of Social TV Analytics as Market Information Regime. Television & New Media, 17(3), 254-271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476415597480 [ Links ]

Lellouche Filliau, I. (2016). Watermarking - a technological innovation for television audience measurement. Mediametrie. https://www.mediametrie.fr/en/watermarking-technological-innovation-television-audience-measurement [ Links ]

Lin, J., Sung, Y. & Chen, K. (2016). Social television: Examining the antecedents and consequences of connected TV viewing. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 171-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.025 [ Links ]

Madinaveitia, E. & Merchante, M. (2015). Medición de audiencias: desafío y complejidad en el entorno digital. Harvard Deusto marketing y ventas, 131, 26-33. https://www.harvard-deusto.com/medicion-de-audiencias-desafio-y-complejidad-en-el-entorno-digital [ Links ]

Méadel, C. (2015). Moving to the peoplemetered audience: A sociotechnical approach. European Journal of Communication, 30(1), 36-49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323114555824 [ Links ]

Mediametrie. (2018). Informe Eurodata TV Worldwide Mediametrie. http://www.mediametrie.fr/webmail/ETV/Newsletter/2018march/n39_etv_march_2018.pdf [ Links ]

Medina, M. & Portilla, I. (2016). Televisión multipantalla y la medición de su audiencia: el caso de las televisiones autonómicas. Icono 14, 14(2), 377-403. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v14i2.960 [ Links ]

Miranda Bustamante, M. Á. & Fernández Medina, F. (2015). Hablándole a la televisión: análisis de las conexiones discursivas entre Twitter y tres programas de contenido político en televisión abierta. Comunicación y Sociedad, 24, 71-94. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v0i24.2523 [ Links ]

Napoli, P. M. (2011). Audience Evolution: New Technologies and the Transformation of Media Audiences. Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Napoli, P. M. (2014). The Local Peoplemeter, the Portable Peoplemeter, and the Unsettled Law and Policy of Audience Measurement in the United States. En J. Bourdon & C. Méadel (Eds.), Television audiences across the world. Deconstructing the ratings machine (pp. 216-233). Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Nelson, J. L. & Webster, J. G. (2016). Audience Currencies in the Age of Big Data. International Journal on Media Management, 18(1), 9-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2016.1166430 [ Links ]

Nielsen. (2018). Glossary. https://www.nielsentam.TV/glossary2/glossaryquery.asp?type=alpha&jump=none [ Links ]

Nightingale, V. (2011). The handbook of media audiences. Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Papí-Gálvez, N. & Perlado-Lamo-de-Espinosa, M. (2018). Investigación de audiencias en las sociedades digitales: su medición desde la publicidad. El profesional de la información, 27(2), 383-393. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.mar.17 [ Links ]

Portilla, I. (2015). Television Audience Measurement: Proposals of the Industry in the Era of Digitalization. Trípodos, 36, 75-92. http://www.tripodos.com/index.php/Facultat_Comunicacio_Blanquerna/article/view/243 [ Links ]

Quintas-Froufe, N. & González-Neira, A. (2016). Consumo televisivo y su medición en España: camino hacia las audiencias híbridas. El profesional de la información, 25(3), 376-383. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2016.may.07 [ Links ]

Quintas-Froufe, N. & González-Neira, A. (2014). Audiencias activas: participación de la audiencia social en la televisión. Comunicar, 43, 83-90. https://doi.org/10.3916/c43-2014-08 [ Links ]

Webster, J., Phalen, P. & Lichty, L. (2005). Ratings analysis: Audience measurement and analytics. Routledge. [ Links ]

4In 2013, Kantar Media introduced the Virtual Meter in a small sample of the Spanish audience panel to measure audiovisual content consumption on devices other than television. Then, in 2015, Comscore and Kantar Media announced the launch of a new cross-platform model to measure the television audience for their main clients, which was introduced in 2016.

5In 2016, Kantar Media selected Spain as a pilot market to develop a cross-media audience measurement system.

6JIC: “Form of survey organization in which a joint industry grouping of TV station, advertiser and media buyer representatives holds a contract with one or more data suppliers for a fixed time period (usually lasting between five and ten years). The functions of the JIC generally include contract specification, supervision of the TAM service, ownership of data copyright, and determination of the conditions for data release” (Nielsen, 2018).

7MOC: “Form of survey organization in which one or more media owners (i.e. TV stations) holds the main contract with the data supplier that guarantees the production and delivery of TAM data. MOC systems vary appreciably in terms of how far the media owners involve themselves in the supervision of the TAM services or in determining commercial policies for relEASIng TAM data to other parties” (Nielsen, 2018).

8“A research institute collects audience data in terms of purely commercial initiative and markets its services through multiple individual contracts negotiated with data buyers. Sometimes the institute accepts or promotes the creation of technical user committees that may somewhat limit its ability to maneuver for the sake of greater user participation” (Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación [AIMC], 2011).

11The meter takes video or audio samples of the channels the panelist is watching or listening to and compares them with the signal of the original broadcast, every certain interval of time (generally, one minute).

12“This technology inserts a mark, inaudible to the human ear, into programmes. This mark contains the identification of the channel which broadcast the programme and the regular broadcast timestamps. The meters installed in panelists’ homes can retrieve this information” (Lellouche Filliau, 2016).

13In 2016, Kantar Media and Movistar signed an agreement to develop the Return Path Data service, according to the operator’s internal data on the consumption of its audiovisual content across any device.

How to cite: González-Neira, A., Quintas-Froufe, N. & Gallardo-Camacho, J. (2020). Television audience measurement: the challenge posed by video streaming platforms. Comunicación y Sociedad, e7284. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2020.7284

Received: September 04, 2018; Accepted: February 19, 2020

text in

text in