INTRODUCTION

The nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere contribute to the formation of photochemical smog and of acid rain precursors, to the destruction of ozone in the stratosphere, and to global warming (Kapteijn et al. 1997). Over the past 150 years, global emissions of nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere have been increasing steadily. A significant amount of the nitrogen oxide emissions is attributed to the combustion of biomass and fossil fuels. Increasingly stringent NOx emission regulations are being implemented in a number of industrialized countries. These regulations have driven the development of NOx emission control techniques (Wu et al. 2015).

An alternative process for the elimination of nitrogen oxides is the adsorption of these gases onto porous adsorbent materials. This method allows the separate adsorption and subsequent desorption of these gases at different temperatures for their treatment or direct application (Longhurst et al. 1993, Kohl et al. 1997). Pure N2O is used, for example, for oxidation reactions (Centi et al. 2000), whereas NO is used as a crucial biological agent in the cardiovascular, nervous, and immune systems (Wheatley et al. 2006)

Natural zeolites may be used because they have a porous structure with high-volume pores where nitrogen oxides could be adsorbed. Also, zeolites can be modified by cation exchange and cations provide active sites that enhance selective adsorption (Centi et al. 2000).

Studies of the adsorption of oxides on synthetic zeolites have already been performed. However, the study of adsorption on natural zeolites is still a non-explored field. Therefore, the main objective of this work was to study the adsorption kinetics of pure N2O on three Mexican natural zeolites at different temperatures and to use the results obtained to find a suitable adsorbent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Three natural zeolites of the erionite (ZAPS), mordenite (ZNT), and clinoptilolite (ZSL) types, from various deposits in Mexico were used. N2O was provided by INFRA (CP grade) with a minimum purity of 99.0 % and was used without further purification.

Characterization of the adsorbents

The adsorbents were characterized using the adsorption of N2 at 77 K. The results obtained were reported in previous studies (Hernández-Huesca et al. 1999).

Adsorption kinetics measurement

Adsorption kinetic uptake was measured using a conventional high vacuum volumetric system constructed entirely of Pyrex glass and equipped with grease-free valves. Vacuum was created by a mechanical pump E2M1.5 (Edwards) reaching residual pressures of 10-3 torr. Pressure was registered by a digital display pressure transducer TPR 017 (Balzers) for pressures in the interval of 10-4 to 1 torr, as well as by a pressure transducer CDG Gauge (Varian) Multi Gage digitally displayed for pressures between 1 and 1000 torr. Before measurement, about 500 mg of each sample (fraction 0.38-0.54 mm) was dehydrated in situ at 300 °C in an oven under constant evacuation, down to a residual pressure of 10-3 torr, and these conditions were maintained for 3 h. Simultaneously, the determination of the weight loss of the adsorbents was evaluated by heating samples up to 300 °C at atmospheric pressure in a conventional oven. After dehydration, the temperature of the samples was reduced until it reached the desired measuring temperature and it was then maintained constant for at least 1 h before starting any measurement. The 0 °C temperature was created by a bath of ice water. The 20 and 60 °C temperatures were controlled by a Haake L. ultra thermostat with a precision of ± 0.15 °C, while the 100 °C temperature was controlled by an oven (Lindberg) with a precision of ± 0.2 °C.

Gas adsorption uptake as a function of time was obtained as the difference between the initial amount of gas introduced into the cell and the amount of gas remaining in the dead space of the cell at any given time between 0 and teq (equilibrium time). The initial pressure was 400 torr in all experiments.

During the kinetic measurements, the pressure decrease in the system was measured manually and this allowed us to write down time and pressure data. The procedure used to perform the kinetic measurements was described in detail in previous papers (Aguilar-Armenta et al. 2001, Aguilar-Armenta et al. 2006). After evacuation of the adsorbent in situ at 300 °C, a kinetic adsorption curve was measured at a given temperature. Subsequently, the sample was evacuated at 300 °C, as in the previous experiment, until a residual pressure of < 10-3 torr was reached for another study.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Adsorption kinetics

Adsorbate uptake curves for N2O were measured from t = 0 up until equilibrium was reached (t → ∞, α = constant).

a) ZAPS.Figure 1 shows the adsorption kinetic curves for N2O on ZAPS at 0, 20, 60, and 100 °C. It can be seen that the adsorbed amount and the adsorption rate diminish with increasing temperature. This behavior allows us to deduce that the adsorption process of N2O is not of the activated type and that it is probably not influenced by kinetic effects, possibly because the kinetic diameter of the N2O molecule is 3.3 Å (Breck 1974) and ZAPS adsorbs molecules with kinetic diameters that do not exceed 4.3 Å.

To study more carefully the effect of temperature on the adsorption rate of gas, the fractional pore filling αlα∞, where α and α∞ are the amounts adsorbed at a given time t and at equilibrium, respectively, was analyzed as a function of time. The adsorption rate of the fractional uptake of N2O on ZAPS is shown in Figure 2. The results show that for times as short as 100 seconds, a 90 % of the total capacity of N2O adsorption is observed. In addition, the adsorption rate of N2O does not depend on temperature in the range of 0-100 °C (Fig. 2), confirming that this process is not an activated diffusion.

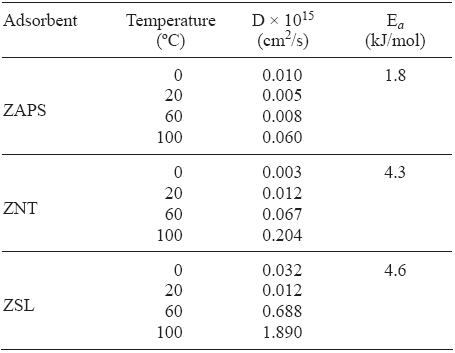

The values of the diffusion coefficients (D, cm2/s) were found by fitting the experimental data by the Barrer equation R = αt - α0/ α∞ - α0 = 2SBET/V(1 + K/K) (Dt/π)1/2 (Barrer 1971). Where K =[(α 0)g - ( α ∞ - α 0]/ α ∞ is the ratio of the adsorbate in the gas phase to that in the adsorbed phase at equilibrium; αt, α0 and α ∞ are the amounts of gas adsorbed at times t, t = 0, and t = ∞ (equilibrium), respectively (in our experiments α0 = 0); 2BET and V are the specific external surface area of the particles (cm2/g) and the volume of the crystals (cm3/g), respectively; (α 0 )g is the amount of gas initially available for adsorption; D is the diffusion coefficient (cm2/s). Table I summarizes the diffusion time constants of N2O on ZAPS at different temperatures. These results show that the diffusion of N2O rises faster with increases of temperature between 20 and 100 °C.

Table I Diffusion coefficients (D) and diffusion activation energies (Eα) of N2O on the studied zeolites: erionite (ZAPS), mordenite (ZNT), and clinoptilolite

The activation energy can be calculated by the equation Eα = [RT1T2/T1]1n[τ 2(0.5)/ τ2(0.5)] (Timofeev et al 1961) Calculations revealed that the energy of activation in ZAPS is 1.8 kJ/mol (Table I).

b) ZSL. The adsorption kinetic behavior at 0, 20, 60, and 100 °C on the ZSL sample for N2O is presented in Figure 3. These results show that the adsorbed amount and the adsorption rate diminish with increasing temperature, as in the case of the ZAPS sample. It can be seen that the adsorbed amounts of N2O on the ZSL sample is lower than that on the ZAPS sample (Fig. 1). The latter could be due to the decrease in micropore accessibility (3.5 Å). The fractional uptakes of N2O on ZSL at different temperatures reveal a great difference in the adsorption kinetic behavior on the ZAPS and ZSL samples (Fig. 4). The adsorbed amounts of N2O on ZAPS, in the range from t = 0 to t = teq (equilibrium) at different temperatures, were greater than that on ZSL. The activation energy on ZSL was 4.6 kJ/mol. These results show that the diffusion of N2O rises faster on ZSL than that on ZAPS as the temperature increases (Table I). Taking into account that the kinetic diameter of N2O is about 3.3 Å, while the ZSL diameter is around 3.5 Å, we believe that these results could be due to the lower micropore participation in the N2O adsorption process.

c) ZNT. The results shown in Figures 5 and 6 reveal a decrease in adsorption uptake when the temperature goes up from 0 to 100 °C in ZNT. These results show that the adsorption process of N2O is not of the activated type and that it is probably not influenced by kinetic effects. Unlike for ZAPS and ZSL, the activation energy was 4.3 kJ/mol. This could be due to the reduction of pore volume that greatly influences the adsorption of the N2O molecule (Hernández-Huesca et al. 1999). The diffusion constants of N2O are of a higher order as temperature increases, these values are also higher to one another (Table I).

Influence of the temperature in the adsorption of N2O

The N2O adsorption capacities decrease in the order ZAPS > ZSL > ZNT at 20 °C (Figs. 1, 3 and 5). Therefore, this adsorption behavior is mainly due to the limiting volume of the micropores of these zeolites and to the quantity of cations available per unit mass of the dehydrated zeolites (cationic density). The cationic density depends on the Si/ Al ratio, which follows precisely the order ZSL ≈ ZNT > ZAPS (Hernández-Huesca et al. 2009). In other words, the adsorption capacity of ZAPS is the greatest because there is a larger amount of Al in this zeolite and, therefore, its cationic density is greater than that of the other two zeolites.

There is a difference between the adsorbed amounts of N2O at 20 °C than at 100 °C. The results show that the adsorption capacities decrease in the order ZSL > ZAPS > ZNT at 100 °C. This behavior suggests that the adsorption of N2O is favored at low temperatures on ZAPS, close to room temperature, whereas the adsorption of N2O is recommended at 100 °C on ZSL.

CONCLUSIONS

Within the temperature range studied, the adsorbed amount and the adsorption rate of N2O diminish with increasing temperature in zeolites. This behavior allows us to deduce that the adsorption process of N2O is not of the activated type and that it is not influenced by kinetic effects. The capacities of these samples to adsorb N2O increase in the order ZNT < ZSL < ZAPS due to higher cationic density (Si/Al) and their corresponding properties. It was established that the adsorption of N2O on ZAPS can be effected most efficiently at ambient temperature (20 °C), whereas the use of ZSL could be recommended at 100 °C. The activation energies (kJ/mol) for the adsorption of N2O were 1.8, 4.3 and 4.6 on ZAPS, ZNT and ZSL, respectively.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)