INTRODUCTION

The incidence and prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) has increased worldwide over the past two decades. In 2016, CKD was the 13th leading cause of global death, whereas in Latin America, CKD ranked as the eighth leading cause of death1. The United States and Mexico have reported the highest incidence of treated CKD, with rates of 378 and 411 per million in the general population, respectively. In Mexico, the incidence of treated CKD increased by 63% and the CKD prevalence by 298% between 2002 and 20152.

Individuals with CKD remain asymptomatic during the early stages and are often diagnosed during advanced stages that require substitution therapy. The annual cost per patient in Mexico is estimated at $12,500 USD, and treating all CKD patients could impose an economic burden of up to $1650 million USD per year3. Older adult population commonly reports a clinical history of cardiometabolic risk factors (CMRFs, i.e., type 2 diabetes [T2D], overweight, obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia) before CKD diagnosis. Notably, two or more of these factors can be detected even 30 years previous to CKD diagnosis.

In a meta-analysis, including 318,898 adults (ages 48-76 years), Tsai et al.4 found that the main risk factors for CKD were male sex (hazard ratio [HR] 1.37; 95% confidence level [CI] 1.17, 1.62), proteinuria >1 g/day (HR 1.64; 95% CI 1.01, 2.66), and diabetes (any type) (HR 1.16; 95% CI: 0.98, 1.38). Thomas et al., in a meta-analysis, including 30,146 subjects, reported that metabolic syndrome (MetS) was associated with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (odds ratio [OR] 1.55; 95% CI 1.34, 1.8), with a positive correlation to the number of individual metabolic components5. Finally, Hill et al., in another meta-analysis, including 6,908,440 subjects older than 35 years, reported that the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension was significantly associated with the prevalence of CKD6.

We recently reported that adolescents and young adults in a cohort of 1st year university students (Iztacala campus, UNAM) were also at increased risk of renal impairment and the quartiles of their serum uric acid (UA) concentrations had a positive correlation with CMRFs7. The Nephrology Department at the General Hospital of Mexico, in 2018, treated 16,587 CKD patients, of whom 7% were young (15-24 years old) and 24% were adults between 25 and 44 years of age8. McMahon et al. found that CKD patients have at least one unidentified risk factor for CKD since the age of 20. Unfortunately, young adults are not systematically screened for these risk factors, as they are presumed to be healthy. This is an alarming fact if we consider that in Mexico, 14.3% of the population is between 18 and 25 years old9.

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted in a young population to identify the CMRFs that best predict the progressive alteration in renal function, predisposing them to future CKD development. Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify the prevalence and strength of association between CMRFs and renal function in young adults 18-25 years of age.

METHODS

Study design and variables

This cross-sectional epidemiological study included 5531 students at the Iztacala School of Graduate Studies, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), Mexico City. Freshman students were invited to participate voluntarily between August 2008 and September 2015 for a brief physical examination and record their anthropometric measurements and resting blood pressure (BP). Blood was drawn for analysis of glucose, UA, lipids, and insulin after 8 h fasting. The following CMRF-related variables were measured (nominal scale): central obesity (Ob) ≥ 90/80 cm for men (M)/women (W), overweight or obesity (high body mass index [hBMI] > 25 or > 30, respectively, according to the WHO classification); high BP (HBP; SBP, DBP, ≥ 130/85 mmHg), hyperglycemia (≥ 100 mg/dL); hyperuricemia (UA > 6.8 mg/dL); hypertriglyceridemia (≥ 150mg/dL), low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C < 50/40 mg/dL W/M), high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C >130 mg/dL), and insulin resistance (IR; homeostatic model assessment [HOMA]-IR, > 2.3/2.9 W/M)10-12. MetS was defined according to the criteria established by the International Diabetes Federation and the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute13. The diagnosis of T2D was made using the American Diabetes Association criteria14.

GFR was estimated by the CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration formula; it was stratified as high (GFR > 130/120 mL/min/1.73 m2 M/W), normal (GFR ≥ 90-120 and 90-130 mL/min/1.73 m2 W/M), and low GFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2). Proteinuria was evaluated with protein reactive strips (ROCHE, Urisys 2400). The presence of ≥ 15-500 mg/dL of protein, without the presence of bacteria, nitrites, hemoglobin, or erythrocytes in the urinalysis was considered positive proteinuria15.

Statistical analysis and ethical considerations

Student’s t-test and z-test were used to assess statistical significance for datasets with continuous variables and proportions, respectively. Logistic regression was performed for OR computation and 95% confidence intervals (CI), adjusted by sex. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05 was reached, and if we could compute of population attributable risk (PAR).

A log-linear model was used to compute the probability of adding the specific risk factors (HBP, UA, HDL-C, and LDL-C) to obesity combined with any kidney disorder (e.g., low GFR, high GFR, or proteinuria). The log-linear model was adjusted with 2-way and 3-way interactions. Coefficients that reached p < 0.10 were maintained in the model. The loadings of main effects were used for the estimation of frequencies, odds, and probability. The estimated frequencies were calculated with:

freq = eα+Σλχ

In this equation, λ is the loading for each variable or interaction and α is the linear intercept; both parameters were used as exponential link for generalized lineal modeling. In these probabilistic models, we considered a variable as clinically significant if it had p > 0.50. All statistical analyses were performed with packages SPSS v.22 and Epidat 3.0.

The study was designed following the Helsinki Declaration and was reviewed and approved by the Committee of Ethics and Institutional Research, registry key DI/16/105-B/04/056. Statistical analysis of the data was carried out during the period of 2017-2018.

RESULTS

Anthropometry, clinical variables, and CMRFs

Anthropometry, clinical characteristics, and the prevalence of risk factors of the sampled subjects are shown in table 1a and b. No CKD risk factor was found in 22% of the subjects (n = 1219). In contrast, 49% of the subjects (n = 2691) had two or more CMRFs for CKD. Women had a higher frequency of two or more risk factors when compared to men (25% vs. 17%, p < 0.001).

Table 1a Anthropometry and clinical data of population, by sex

| Total n = 5531 (%) | Men n = 1781 (32%) | Women n = 3750 (68%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (x ± SD) | 19.31 ± 1.6 | 20 ± 2 | 19 ± 2 | < 0.001 |

| BMI kg/m2 (x ± SD) | 24.12 ± 4.27 | 24.41 ± 4.38 | 23.99 ± 4.22 | < 0.001 |

| Underweight (%) | 267 (5) | 77 (4) | 190 (5) | 0.25 |

| Appropriate weight | 3322 (61) | 1041 (59) | 2281 (62) | 0.09 |

| Overweight | 1331 (24) | 438 (25) | 893 (24) | 0.54 |

| Obesity I | 437 (8) | 173 (10) | 264 (7) | < 0.001 |

| Obesity II | 93 (2) | 30 (2) | 63 (2) | 0.92 |

| Obesity III | 19 (1) | 7 (0.4) | 12 (0.3) | 0.85 |

| WC (cm) | 81.9 ± 11.21 | 84.44 ± 11.65 | 80.71 ± 10.79 | < 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 73 ± 9 | 77 ± 9 | 71 ± 9 | < 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 108 ± 12 | 114 ± 12 | 105 ± 11 | < 0.001 |

| Central obesity (WC) | 2164 (39) | 449 (25) | 1715 (46) | < 0.001 |

| Ow/OB (BMI) | 1880 (34) | 648 (37) | 1232 (33) | 0.01 |

| UA > 6.8 mg/dL | 688 (12) | 584 (33) | 104 (3) | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL | 956 (17) | 389 (22) | 567 (15) | < 0.001 |

| Cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL | 639 (12) | 199 (11) | 440 (12) | 0.57 |

| HDL-C risk | 2568 (46) | 509 (29) | 2059 (55) | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C > 130 mg/dL | 437 (8) | 147 (8) | 290 (8) | 0.53 |

| Glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL | 428 (8) | 203 (11) | 225 (6) | < 0.001 |

| SBP ≥ 130 mmHg | 321 (6) | 221 (13) | 100 (3) | < 0.001 |

| DBP ≥ 85 mmHg | 412 (8) | 237 (13) | 175 (5) | < 0.001 |

| Proteinuria¤ | 170 (3) | 69 (4) | 101 (3) | 0.03 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 732 (13) | 264 (15) | 468 (13) | 0.01 |

| HOMA-IR* | 723 (25) | 266 (37) | 457 (63) | 0.002 |

Results of continuous variables presented as mean ± standard deviation; categorical variables, as proportions.

*HOMA-IR: subsample of 2884 subjects. n = 5430; Men: 1775; Women: 3655; Central obesity: WC ≥ 90 cm in men, ≥ 80 cm for women.

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; Ow, overweight; OB, obesity; UA, uric acid; HDL-C risk: < 50 mg/dl for

women/< 40 mg/dl in men.

WC, waist circumference.

Table 1b Biochemical parameters, by sex (continued)

| Total n = 5531 (100%) | Men n = 1781 (32%) | Women n = 3750 (68%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 15.36 ± 1.41 | 16.9 ± 0.9 | 14.6 ± 1 | < 0.001 |

| Total leukocytes 103/µL | 7.19 ± 1.71 | 6.65 ± 1.56 | 7.46 ± 1.73 | < 0.001 |

| Platelets 103/µL | 298 ± 62.7 | 274 ± 58 | 310 ± 62 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 4.5 ± 0.29 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | < 0.001 |

| Urea° (mg/dL) | 24.7 ± 6.65 | 27.8 ± 6.5 | 23.2 ± 6.2 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.81 ± 0.15 | 0.95 ± 0.12 | 0.76 ± 0.13 | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 112 ± 66 | 121 ± 89 | 108 ± 51 | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 166 ± 30 | 165 ± 30 | 166 ± 30 | 0.24 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 95.2 ± 24.6 | 96 ± 25 | 95 ± 25 | 0.16 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 47.9 ± 9.8 | 45 ± 9 | 49 ± 10 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 89.1 ± 9.4 | 91 ± 11 | 88 ± 8 | < 0.001 |

| UA (mg/dL) | 5.1 ± 1.37 | 6.28 ± 1.24 | 4.55 ± 1.05 | < 0.001 |

| eGFR mL/min/1.73 m2 | 114.6 ± 12.81 | 115 ± 13 | 114 ± 13 | 0.007 |

| Insulin IU* | 10.15 ± 6.25 | 8.72 ± 5.28 | 10.8 ± 6.56 | < 0.001 |

*Subsample of 2884 subjects. Results of continuous variables presented as mean ± standard deviation. WC, waist circumference;

c, cholesterol; UA, uric acid; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. °n = 1693 (men 564, women 1129).

Only 1% of the students (n = 59) had hypertension (BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg) and eight subjects had T2D. HOMA-IR was measured in a subsample of 2884 subjects (68% [n = 1959] were women). The mean serum concentrations of insulin in women were 10.8 ± 8.7 IU and in men were 8.7 ± 5.2 IU (p < 0.001). IR was found in 25% (n = 723) of the subjects (Table 1).

Renal function

Renal function stratified by sex and presence of proteinuria is presented in table 2. Proteinuria was found in 3% (n = 170) of individuals and was more frequent in males (4% vs. 3%, p = 0.02). High GFR (hyperfiltration) was found in 33% (n = 1830) of the subjects and was more common in females (43% vs. 8%, p < 0.01). Low GFR was identified in 3% of the subjects (n = 161).

Table 2 Renal function and proteinuria

| eGFR mL/min/1.73 m2 | Proteinuria | p** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women n = 3655 (67%) | Men n = 1775 (33%) | |||||

| Total n = 5430 (%) | With proteinuria n = 101 (3%) | Without proteinuria n = 3554 (97%) | With proteinuria n = 69 (4%) | Without proteinuria n = 1706 (96%) | ||

| < 15 | 1 | 1 (0.27) | | | | |

| 15-29 | | 0 | | | | |

| 30-59 | 3 | 1 (0.27) | | 1 (0.027) | 1 | |

| 60-89 | 157 (3) | 9 (0.25) | 83 (2.2) | 8 (0.45) | 57 (3.2) | 0.31 |

| ≥ 90 | 3494 (64) | 57 (1.5) | 1882 (51.4) | 57 (3.2) | 1498 (84.4) | < 0.01 |

| > 130 M, > 120 W* | 1775 (33) | 33 (0.9) | 1589 (43.4) | 3 (0.16) | 150 (8.4) | < 0.01 |

*Adjusted by sex M: men and W: women. Results of categorical variables presented as proportions.

**Value of p, obtained when comparing the frequency of proteinuria by sex. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

CMRFs and renal function

The CMRFs associated with low GFR were UA (OR = 1.8), hypercholesterolemia (OR = 1.66), and proteinuria (OR = 3.4) and those associated with high GFR were hBMI (OR = 1.3), hyperuricemia (OR = 0.2), and HDL risk (OR = 1.4). Proteinuria was associated with hyperuricemia (OR = 1.59) and with hypercholesterolemia (OR = 1.8). Table 1S shows additional details of the relation between CMRFs and renal function.

Table 1S Multivariate analysis for cardiometabolic risk factors and renal function, adjusted by sex

| eGFR < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2sc* | eGFR > 130 M, > 120 W mL/min/1.73 m2sc** | Proteinuria*** | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95% CI | p | PAR (%) | ORa | 95% CI | p | PAR (%) | ORa | 95% CI | p | PAR (%) | |

| Ow/OB | 0.93 | 0.67-1.3 | 0.74 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 1.14-1.47 | < 0.001 | 11 | 0.99 | 0.66-1.4 | 0.98 | 0.41 |

| SBP and/or DBP | 1.08 | 0.52-2.24 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 0.76 | 0.51-1.15 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.99 | 0.92-4.3 | 0.08 | 3.2 |

| Glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL | 1.18 | 0.71-1.9 | 0.51 | 1.7 | 0.90 | 0.71-1.15 | 0.41 | 0.7 | 0.71 | 0.33-1.5 | 0.71 | 3.1 |

| UA > 6.8 mg/dL | 1.8 | 1.3-2.6 | 0.001 | 13 | 0.2 | 0.15-0.26 | < 0.001 | 13 | 1.59 | 1.01-2.5 | 0.04 | 8.3 |

| Triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL | 0.93 | 0.61-1.4 | 0.93 | 1.6 | 0.82 | 0.69-0.98 | 0.03 | 3 | 0.70 | 0.41-1.2 | 0.21 | 7.5 |

| LDL-C > 130 mg/dL | 1.66 | 1.05-2.6 | 0.02 | 6 | 0.84 | 0.66-1.07 | 0.16 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.03-3.1 | 0.039 | 5.7 |

| HDL-C risk | 1.02 | 0.74-1.4 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 1.4 | 1.2-1.6 | < 0.001 | 16 | 1.07 | 0.72-1.5 | 0.7 | 2.8 |

| MS | 1.4 | 0.74-2.8 | 0.27 | 6.3 | 0.92 | 0.75-1.13 | 0.45 | 1 | 1.07 | 0.44-2.5 | 0.87 | 1.08 |

| Proteinuria | 3.4 | 2.07-5.7 | < 0.001 | 8 | | | | | | | | |

Data presented as odds ratio (95% confidence interval), adjusted model by sex.

*OR estimated by comparing normal eGFR versus eGFR < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2.

**OR estimated when comparing subjects with eGFR > 130 for men, > 120 women mL/min/1.73 m2 versus subjects with adequate eGFR.

***OR estimated when comparing subjects with proteinuria versus no proteinuria, or hyperfiltration or eGFR < 90 mL/min/1.73m2.

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; Ow/OB: overweight or obesity by BMI and/or waist circumference; SBP: systolic blood pressure

(≥130 mmHg) and/or DBP: diastolic blood pressure (≥ 85 mmHg). HDL-C risk: < 50 mg/dL women, < 40 mg/dL men; MS: metabolic syndrome. PAR (%): population attributable risk

IR and renal function

Table 3 shows the estimations of crude and adjusted OR by sex for IR and impaired renal function. IR was significantly associated with high GFR (OR = 1.3), whereas the PAR for proteinuria was 14%.

Table 3 Insulin resistance associated to renal function*

| OR | 95% CI | p | ORa* | 95% CI | p | PAR (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKD-EPI < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 0.76 | 0.47-1.2 | 0.26 | 0.77 | 0.48-1.2 | 0.29 | 6.07 |

| eGFR > 130 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1.09 | 0.90-1.3 | 0.35 | 1.3 | 1.05-1.7 | 0.01 | 5.9 |

| Proteinuria | 1.8 | 0.99-3.3 | 0.52 | 1.81 | 0.98-3.3 | 0.057 | 14 |

*Analysis performed in subsample of 2785 subjects (IR = 25%). Data presented as odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

**OR adjusted by sex. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CKD, chronic kidney disease; PAR, population attributable risk.

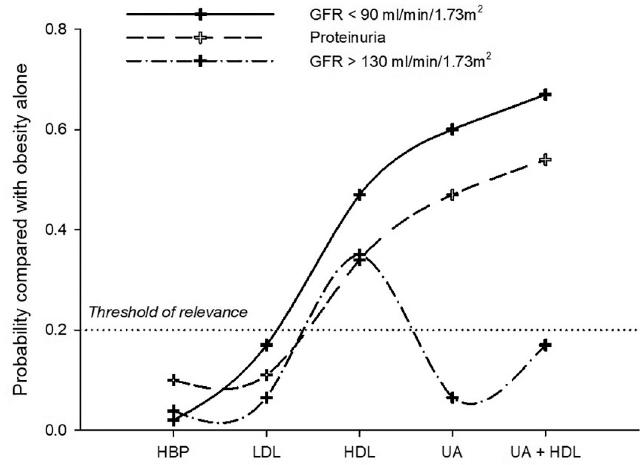

Figure 1 shows the probability (using a log-linear model) of having low/high GFR or proteinuria in the presence of obesity and other CMRFs when compared to obesity alone. The threshold of clinical relevance was defined as p > 0.2 (20%) when compared to obesity alone. The presence of obesity with low HDL-C, high UA, or their combination increases the likelihood of having low GFR and proteinuria. Meanwhile, hyperfiltration probability was slightly increased with obesity and low HDL-C, but not with UA.

Figure 1 Log-linear model of the probability of having low or high glomerular filtration rate or proteinuria in the presence of obesity and other CMRFs when compared to obesity alone. HBP: high blood pressure; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; UA: uric acid; CMRFs: cardiometabolic risk factors.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that 76% of our study population comprising 1st year university students had at least one CMRF associated with a future CKD risk. This young population is considered healthy, and due to this misconception, they are not either screened for any risk factor or are any interventions implemented in them to modify risk factors9,16. Obesity, when combined with other CMRF9,17,18, can lead to progressive decrease in GFR. Such a decrease can start 30 years before CKD diagnosis in adulthood9,18-24. Adolescents in Mexico have a 36% prevalence of overweight and obesity, and during early adulthood (20-29 years), the prevalence increases to as much as 72%25.

BP levels, although still in the normal range, were closer to the upper threshold (130-139/85-89 mmHg), and this may double the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD) and could increase CKD risk in the future26-28. In our population, 13% of the students had marginally elevated BP levels, and only 1% showed hypertension. Regarding dyslipidemias, our sample showed a high prevalence of low serum HDL-C (46%) followed by hypertriglyceridemia (17%) and hypercholesterolemia (11.5%). All of them are associated with CKD development16,29-31 and could be detected 30 years before CKD diagnosis9,31.

Elevated level of UA is an asymptomatic CMRF found in 12% of our young population. It is known that the development of CKD is related to the duration of exposure to elevated levels of UA. The proposed mechanisms are endothelial dysfunction; glomerular hypertrophy; proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, secondary to the activation of cyclooxygenase-2 plus MCP-1; and the activation of the renin-angiotensin system32-36. Interestingly, our log-linear model suggested the combination of obesity and hyperuricemia, which gave p = 0.6 of low GFR when adding low HDL-C increased it to 0.66. Early intervention in this age group could help to reduce the impact of this risk factor in the long term.

The presence of MetS36 portends increased risk to CKD development after 20 years6,37. Our cross-sectional findings suggest that the sum of CMRFs does not confer a greater risk, but the presence of each component separately and a combination of specific CMRFs might have a better predictive value. This finding supports the need to tailor the current MetS criteria based on the specific population under study for accurate model development to predict CKD in the young population.

We found low prevalence (<1%; n = 4) of GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 in students, compared with students in Thailand, where the prevalence of CKD was 6.8%. We found that 3% of our subjects had low GFR, which is similar to the prevalence reported by Hill et al.6

In the previous studies, high GFR was not evaluated as an incipient marker of impaired renal function, but some studies reported an association with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality38. We found that 33% of young people with this condition were associated with IR (OR 1.3), HDL-C of risk (OR 1.4), and hBMI (OR 1.3). We also found that UA concentrations <6.8 mg/dL were inversely correlated with GFR (OR 0.2, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.26, p < 0.001), in accordance with the previous studies34. Our log-linear analysis supports a model where a combination of two or more CMRFs is associated with high GFR with p > 0.4.

A limitation of our study is the lack of a second measurement of proteinuria, as currently recommended. In our population, after excluding participants with suspected menstruation period, urinary infections or suspected secondary causes for the presence of urinary protein, the prevalence of proteinuria was 3%, which is in agreement with reports from other authors35,39,41. The presence of proteinuria has been previously associated with hypercholesteremia18,42 and high levels of UA (OR 1.59). The use of dipstick is common in epidemiological research. A meta-analysis examined potential sources of heterogeneity among studies and found no difference between the strips compared with laboratory measurement (RR 1.4, 95% CI 1.2, 1.7 vs. 1.7, 95% CI 1.2, 2.5; p = 0.5)43. However, the same group reported that the dipsticks have slightly lower sensitivity for the prediction of stroke whn compared to laboratory measurement44.

Interestingly, 30% of the students with renal function abnormalities did not have any of the examined risk factors, which suggests that factors not assessed during this study may be potentially involved in possible CKD development. These may include dietary habits, inheritance/family history, tobacco/alcohol consumption, and interaction of genes with environmental factors.

Reproducibility of proteinuria prevalence is hard to define. A study in young population (although older than our sample) found a prevalence of proteinuria of 2.5% in male and 1.7% in female subjects, using dipstick for urine45. Research conducted in Mexico in adult population46 found 14% prevalence of microalbuminuria; however, this study did not include young subjects. Since we could not verify the validity of our results in an independent cohort, we have ongoing studies in three Mexican universities, two of them in Reynosa, Tamaulipas (Universidad Mexico-Americana del Norte and Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas) and one more in Monterrey (Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León), which will allow us to confirm our results in additional cohorts.

There is a high prevalence of CMRFs in otherwise “apparently” healthy Mexican young adults and adolescents. The coexistence of some of these risk factors such as hyperuricemia, hBMI, and HDL-C predicts altered renal function which increases the risk of development and progression of CKD and CVD21-23. Based on our findings, it is appropriate to consider the implementation of public health measures focused on the detection and timely treatment in this age group, which could have a positive health impact by decreasing the risk of development and progression of CKD and CVD in adulthood.

In conclusion, our findings revealed that young individuals have unexpected high prevalence (about 30%) of abnormal findings in renal function, and more than 70% had at least one CMRFs. Among CMRFs, hyperuricemia, hBMI, and HDL-c of risk predict alterations in renal function. Finally, there is a need for public health programs focused on the detection and timely treatment in this age group to impact on the development and progression of renal diseases.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Revista de Investigación Clínica online (www.clinicalandtranslationalinvestigation.com). These data are provided by the corresponding author and published online for the benefit of the reader. The contents of supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)