INTRODUCTION

Cyanobacteria, often referred as blue-green algae, are photoautotrophic microorganisms distributed ubiquitously in the world and are common inhabitants of a wide range of freshwater bodies. Favorable conditions, such as warm water, a stable water column, high phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations, high pH, low CO2 availability and low herbivory (Zurawell et al., 2005, Glibert & Burkholder 2018, Metcalf et al., 2021), may lead to increased population growth of cyanobacteria generally called “cyanobacterial blooms” (Mowe et al., 2015, Buratti et al., 2017, Moreira et al., 2022). Increases in cyanobacterial cell concentration reduces oxygen concentration and increases ammonia release when cyanobacteria decay. Blooms result in increased turbidity, leading to the decline of other primary producers, and they can enhance the likelihood of production of unpleasant taste and odor compounds (Hudnell & Dortch 2008, Wood 2016). Of major concern is increased levels of cyanotoxins that can be produced in about 40 cyanobacteria genera (Apeldoorn et al., 2007, Singh & Dhar 2013). Cyanotoxins are secondary metabolites of diverse chemical structure and toxicity, including cyclic peptides, alkaloids, non-proteinogenic amino acids, phosphate ester and lipopolysaccharides (Aráoz et al., 2010, Svirčev et al., 2019). Based on their toxic effects in vertebrates, cyanotoxins are classified as hepatotoxins (microcystins, nodularin), neurotoxins (saxitoxins, anatoxins, homoanatoxin-a, B-methylamino-L-alanine), cytotoxins (cylindrospermopsins), dermatoxins (aplysiatoxin, debromoaplysiatoxin, lingbyatoxin) and endotoxins (lipopolysaharides) (Apeldoorn et al., 2007, Svirčev et al., 2019).

The frequency and magnitude of cyanobacterial blooms has received much more scientific attention around the world over the past decades, with blooms generally associated with the increment of eutrophication in freshwaters bodies, watershed modifications and climate change (Paerl & Huisman 2009, Brooks et al., 2016, Glibert 2020, Munoz et al., 2021, Chorus et al., 2021). The toxigenic and adverse effects of cyanotoxins in several groups of organisms have been recognized in field and laboratory settings including bacteria, microalgae, zooplankton, fishes, amphibians, birds, mammals and agricultural plants (Apeldoorn et al., 2007, Valdor & Aboal 2007, Tillmanns et al., 2008, Chen et al., 2016, Banerjee et al., 2021, Zhang et al., 2021). This has led to a growing global consensus of the harmful effects for aquatic organisms and human health due to cyanotoxin exposure (Drobac et al., 2013, Wood 2016, Cantoral Uriza et al., 2017, Scarlett et al., 2020). Specifically for humans, there are well documented events of poisoning that indicate that cyanotoxins were the cause of the symptoms (Humpage and Cunliffe, 2021), however, literature related to human intoxication by cyanotoxins exposure must be taken with caution since, usually, other potential causing agents (e.g., other bacteria and pollutants) have not been simultaneously evaluated (Testai et al., 2016; Humpage and Cunliffe, 2021). In addition, there are other social and economic problems associated to toxic cyanobacterial blooms, including cattle and companion animal deaths, loss of recreational fishing and irrigation value of water bodies, closures of drinking water supplies (Wood 2016, Munoz et al., 2021) and loss of biodiversity (Hudnell & Dortch 2008).

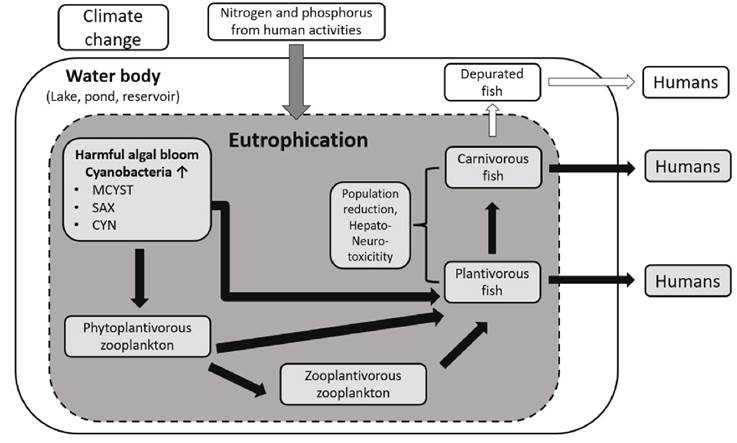

At a global scale, cyanotoxin presence in water bodies (Buratti et al., 2017, Svirčev et al., 2019), accumulation in freshwater organisms (Ettoumi et al., 2011, Testai et al., 2016, Flores et al., 2018, Pham & Utsumi 2018), and their transfer in aquatic food webs (Ferrão-Filho & Kozlowsky-Suzuki 2011, Lance et al., 2014), have been documented and reviewed, highlighting the potential transfer to humans by fish or shellfish consumption (Fig. 1). For example, Sotton et al., (2014) in Lake Hallwil (Switzerland) demonstrated the transfer of microcystins (MCYST’s), produced during a bloom of the filamentous cyanobacteria Planktothrix rubescens (De Candolle ex Gomont) Anagnostidis & Komárek, from filter-feeders herbivorous zooplankton to predator zooplankton. Consequently, this zooplankton contributed to the contamination with MCYST’s of the zooplanktivorous whitefish (Coregonus suidteri Fatio, 1885), a species with commercial value in that region. The evidence of biomagnification of cyanotoxins (i.e., the increase of concentrations in organisms as the toxin moves up the food chain) has only partial support and is still debated (Kozlowsky-Suzuki et al., 2012, Flores et al., 2018).

Figure 1 Schematic representation of cyanotoxins production and trophic transfer between several organisms in water bodies. Black arrows represent the cyanotoxins transfer.

In Latin America (i.e., México to Argentina) the presence of cyanobacterial blooms and cyanotoxins in water bodies have been reported in several countries through field research and review papers, including: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Guatemala México, Perú, Uruguay, Venezuela (Avendaño Lopez & Arguedas Villa 2006, Dörr et al., 2010, Vasconcelos et al., 2010, Gomez et al., 2012, Mowe et al., 2015, Pérez-Morales et al., 2016, Rico-Martínez et al., 2017, Moura et al., 2018, León & Peñuela 2019, Munoz et al., 2021, Salomón et al., 2020). MCYST’s are the most commonly reported cyanotoxins, followed by cylindrospermopsins (CYN’s) and saxitoxin (STX’s), and less commonly anatoxins (ATX’s) and nodularin (NOD) (Galanti et al., 2013, Sunesen et al., 2021).

Despite the knowledge of cyanobacterial blooms and cyanotoxin presence in Latin America, relevant topics related to cyanotoxin impacts on the environment, including field studies on accumulation of cyanotoxins by freshwater organisms (Fig. 1), have not been reviewed for the region. Bioaccumulation of cyanotoxins is directly correlated with the potential human health risk from ingestion of contaminated tissue from organisms such as fish and shrimp. Moreover, in face of the climate change, population increase, watershed modifications and eutrophication increase, it is expected that cyanobacterial blooms will continue. Thus, there is a need of integrative analyses summarizing the knowledge on cyanotoxins bioaccumulation to highlight the potential impacts on freshwater organisms and on human health in Latin America, which could contribute to define a baseline for future studies, and to show pending topics of research. Based on the later ideas, in this review we aimed to summarize the current knowledge of cyanotoxins accumulation in freshwater organisms in Latin America. We analyzed and summarized major topics shared by studies in the region (i.e., depurations of cyanotoxins by organisms in field studies, potential human intake), highlighting the gaps in current knowledge and principal future directions in the region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An extensive literature search was conducted to construct a database including information on accumulation of cyanotoxins in organisms inhabiting freshwater environments in Latin America. We collected all published studies to March 2022, using combinations of relevant search terms (i.e., cyanotoxins, Latin America, bioaccumulation, reservoir, aquaculture, cyanobacteria, human health impact) from the Digital Library of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, which includes about 170 scientific databases (e.g., Scopus, Web of Science, SciFinder) and Google Scholar. We focused on freshwater field studies in Latin America (from México to Argentina) reporting concentrations of cyanotoxins in organisms and water in natural or artificial/manipulated environments (e.g., ponds for aquaculture, reservoirs for hydroelectric energy). Because analytical methods for determination of concentrations of cyanotoxins in food matrices (e.g., fish and shrimps) is crucial to obtain reliable data, we followed Testai et al., (2016) and Ibelings et al., (2021) on determining the suitability and validation of the analytical methods employed in the studies.

From each study we collected the following information: author, year, country, location, freshwater environment type (e.g., lake, reservoir, pond), uses of the water body and land uses around it, reported nutrient concentrations (e.g., eutrophic), cyanotoxins analyzed and principal cyanobacterial genus/species present known to produce the toxins. For the land uses around the water body, if not reported in the study, we searched for this information in published literature. For the species accumulating cyanotoxins we collected: scientific name, native or introduced, importance in fishing (i.e., aquaculture, commercial/subsistence fishery), tissues and number of samples analyzed and concentrations of cyanotoxin in tissues. When studies reported several species that accumulate cyanotoxins or the same species from several water bodies, information from each species or water body was registered as a different entry in the database. Data about concentrations of cyanotoxins in water was included as reported: diluted, in seston (particulate material in water) and/or total. When not directly reported, cyanotoxin concentration values were extracted from figures. Additionally, we collected information related to temporal fluctuations of cyanotoxins bioaccumulation, cyanotoxins depuration by organisms in field studies and potential human cyanotoxin intakes by consumption of contaminated organisms, which are developed in the next sections.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Information from studies reporting cyanotoxins accumulation in freshwater organisms in Latin America was extracted from journal articles (n=20) and a master thesis (n=1). Cyanotoxins bioaccumulation has been studied only recently in Latin America, since the year of publication of studies found ranged from 2001 to 2020. From these, we gathered a total of 50 entries of several species accumulating cyanotoxins in the database in 27 different locations/water bodies (Table S1). The summary and discussion of the information presented below are referred to the 21 studies and 50 entries.

Considerations of analytical methods employed. In order to evaluate the reliability of the analytical methods used in the determination of cyanotoxins concentration in food matrices, including fish and invertebrates, Testai et al., (2016) developed a 1 to 4 score system, where score 1 constitutes a reliable study without restriction (validated method); score 2, a reliable study (fully characterized method); score 3, a reliable study with restriction (only reporting recovery); and 4 denoted a not reliable study (no report of recovery). Based on that score system, which does not depend exclusively on the analytical method, the main difference between a reliable and a non-reliable study is to report the % of recovery, often by spiking samples with known concentrations of analyte. It allows to detect the losses of cyanotoxin during sample processing and cleaning previous to the analytical determination method. It is in accordance with Flores et al., (2018), which pointed, in their global study of accumulation of MCYST’s in fish, that there is a need to standardize cyanotoxin extractions from tissues and analytical methods for quantification, or to report extraction efficiencies, since the method used is likely important in influencing the observed cyanotoxins concentration in tissues.

The analytical methods of cyanotoxins quantification in the database included high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC, 12 studies), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, 10 studies) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS, two studies) (Table S1). However, only 5 studies (25%) reported the % of recovery of the corresponding cyanotoxin analyzed, all of them using HPLC (Cazenave et al., 2005, Amé et al., 2010, Galanti et al., 2013, Morandi 2015, Calado et al., 2019). The other 15 studies would be considered including “a not reliable analytical method” based on Testai et al., (2016) score system. Additionally, 50% of the studies included ELISA as analytical method, which has been considered a semiquantitative method, requiring confirmation of identity (i.e., cyanotoxins variants), and quantity, with strategies to determine extraction efficiency and matrix effects, even more when it is used in a human risk assessment (Testai et al., 2016, Lawton et al., 2021, Ibelings et al., 2021). Unfortunately, it is not the case in studies employing ELISA in Latin America: recoveries were not reported and confirmatory identity of cyanotoxins (and their variants) with a chemico-analytical method were usually not carried out. Exceptions are found in Berry & Lind (2010) and Berry et al., (2011) where CYN’s (by HPLC-UV and LC-MS) and MCYST variants (by LC-MS) where confirmed respectively.

Despite the noted pattern of limitations in the analytical methods employed in most of the Latin America studies and differences in cyanotoxins extraction methods used that were similar to the patterns found by Testai et al., (2016) in their comprehensive review, we decided to continue summarizing the information about cyanotoxins bioaccumulation of the region, at least in a screening sense, in order to 1) visualize its geographically reported occurrence, 2) to call attention of the potential transfer of cyanotoxins by contaminated fish to humans and 3) to highlight the need of use reliable analytical methods especially when evaluating potential human risk exposure.

Distribution, water bodies and cyanotoxin types. Despite the global distribution of cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins (Mowe et al., 2015, Flores et al., 2018, Svirčev et al., 2019) and the known potential risk for species that are exposed to cyanotoxins, including humans (Codd et al., 2005, Buratti et al., 2017, Cantoral Uriza et al., 2017, Pham & Utsumi 2018, Banerjee et al., 2021), cyanotoxins accumulation in freshwater organisms in Latin America has been evaluated only in four countries. Brazil is the country having more field studies of cyanotoxins bioaccumulation (13 studies), followed by México (4), Argentina (3) and, finally, Uruguay with only one study. Of the entries in the database, 37% comprise natural lake environments, and the others comprise artificial environments, including reservoirs (49%) and ponds for aquaculture (14%). Of special concern is the use of water in lakes and reservoirs for the potential cyanotoxin transfer to humans. For example, in natural lakes, the uses include mainly fishing and tourism, besides irrigation and aquaculture. Reservoir’s water is mainly used for electric power generation and drinking water supply (increasing the risk of direct exposition to cyanotoxins by human). However, recreation, aquaculture and fishing are also important activities (Table S1). Notably, 80% of the water bodies included in our database are considered eutrophic, a nutrient condition (i.e., high phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations in water) widely associated with harmful cyanobacterial blooms worldwide (Glibert 2020, Chorus et al., 2021). Clearly, human activities around the water bodies, and its corresponding watershed basin, alter the nutrients dynamics, indirectly by runoff from agriculture fields, pastures for livestock, vicinity of cities, and directly when sewage is discharged in the water bodies (Friesen, 2015). Most of the locations/water bodies included in the database, where information was available (Table S1), are bordered by agricultural fields and/or grassland, sometimes with a large associated human population. For example, Funil reservoir, constructed on the Paraíba do Sul River located near Rio de Janeiro in southern Brazil, has a catchment area of 12800 km2 and is one of the most highly industrialized regions in Brazil. Approximately 2 million people live inside the catchment area in 39 cities that depend on the Paraíba do Sul River for their water supply (Deblois et al., 2008, Pacheco et al., 2015).

Almost all studies reported the principal cyanobacterial species/genus present in water bodies responsible of toxins production. Microcystis is the most reported genus producing toxins in Latin America, found in 11 studies and 13 different water bodies, followed by Cylindropermopsis (8 studies and 10 water bodies) and Anabaena (5 studies, 5 water bodies). Other less reported genera included Planktothrix, Aphanizomenon, Pseudanabaena and Dolichospermun, however, more than one genus was also detected within a water body (Table S1). Studies of cyanotoxins accumulation in Latin America have focused on four toxins with MCYST’s being the most investigated with 15 studies in 25 different water bodies, followed by STX’s, CYN’s and NOD (Table 1). This result agrees with global research about cyanotoxin accumulation and distribution, where MCYST’s are the most studied (Flores et al., 2018), and highlights the need for more comprehensive studies including other cyanotoxins in Latin America.

Table 1 Cyanotoxins analyzed in accumulation studies in freshwater environments in Latin America. Some studies included more than one cyanotoxin or waterbody.

| Cyanotoxin | Countries | Number of studies | Number of waterbodies | Group analyzed |

| MCYST’s | Argentina, Brazil, México, Uruguay | 15 | 25 | fish, snail, zooplankton |

| STX’s | Brazil, Mexico | 6 | 3 | fish, snail, zooplankton |

| CYN’s | Mexico | 2 | 1 | fish, snail, zooplankton |

| NOD | Argentina | 1 | 1 | shrimp |

Taxonomic groups and species accumulating cyanotoxins. Of the groups and species studied accumulating cyanotoxins in freshwater environments in Latin America, fish comprised most of the entries (90% of entries). Other entries corresponded to invertebrates: 2 entries for both snails and zooplankton (4% each group) and one entry for shrimps (2%). Mexico and Argentina are the countries where the invertebrate species accumulating cyanotoxins have been studied. In Mexico, Berry & Lind (2010) reported concentrations of STX’s and CYN’s accumulated in the Lake Catemaco endemic snail species, Pomacea patula catemacensis (Baker, 1922), locally known as “tegogolos”, a relevant species because it is both the target of local and commercial fishing. That study was the first report showing evidence of accumulation of STX’s and CYN’s in any organism in México, and for CYN’s the first report in Latin America. Also in México, two studies analyzed concentrations of cyanotoxins in zooplankton, an ecologically important group which can act as a vector of cyanotoxins, since some zooplankton directly consume cyanobacteria, and also are consumed by other zooplankton or fish (Sotton et al., 2014). Berry et al., (2012) found accumulations of STX’s and CYN’s in copepods (mainly Mesocyclops and Arctodiaptomus) from Lake Catemaco, while Zamora-Barrios et al., (2019) reported MCYST’s accumulation in copepods (Acanthocyclops) and cladoceran (Daphnia and Bosmina) from Lake Zumpango. In both studies, the concentrations of the cyanotoxins in zooplankton were notably higher than the concentrations in fish tissues. Zooplankton may ingest toxins directly from cyanobacteria and/or absorb dissolved cyanotoxins from water (Karjalainen et al., 2005), which could explain their higher cyanotoxin concentration than fish, but this hypothesis should be tested. Finally, for invertebrates, Galanti et al., (2013) carried out field exposures of the shrimp Palaemonetes argentinus (Nobili 1901) in San Roque Reservoir, Argentina, after a cyanobacteria bloom containing NOD. After three weeks of exposure in the reservoir, NOD was detected in P. argentinus tissues. Galanti et al., (2013) noted that their study was the first report of NOD in South America freshwaters, and according to the present review, it is the first and unique report to date of accumulation of NOD in any freshwater organism. Also, it is the only report of the accumulation of cyanotoxins in shrimp in Latin America.

Twenty fish species have been studied related to accumulation of cyanotoxins in Latin America, most of which are native species (70%) (Table 2). México is the country with more species (14), followed by Brazil (5). Argentina and Uruguay included only one species. Only four studies included more than one fish species and Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus 1758), is the most studied species, included in 8 studies. Most of the species showing accumulation of cyanotoxins have commercial importance (80%) by aquaculture, commercial and/or subsistence fishing, highlighting the potential exposure of cyanotoxins to humans (Table 2). Muscle is the most analyzed fish tissue for determination of concentration of cyanotoxins in 16 species and 47 entries in database, followed by liver (6 species, 23 entries), other tissues analyzed in some species included gills, intestine, bile, brain, gonads or whole fish (Table 2, Table S1). The analysis of several types of tissues is important because they usually show distinct patterns of cyanotoxins accumulations, and eventually could produce different harmful effects in fish and on human health. For example, among the tissues, the concentrations of MCYST’s are often reported to be higher in liver (and viscera) relative to concentrations in the muscle (Romo et al., 2012, Flores et al., 2018). For 20 of 21 entries of our database that reported both muscle and liver concentrations of cyanotoxins (corresponding to 6 species used in aquaculture or commercial fishing), the concentration in the liver was reported to be higher than in the muscle. This is in agreement with the global pattern of Flores et al., (2008). This tendency is important because the liver, and the viscera in general, are normally not eaten and are discarded in aquaculture fish (e.g., Nile tilapia, which comprised 16 of the 20 entries), and it is a manner to reduce the risk of human exposure when eating fish that has accumulated cyanotoxins. There are two studies including whole fish consumption in México. The fish genus Chirostoma, locally known as “charales”, is widely captured in lakes and reservoirs in Central Mexico; they are small fish which are sold whole, fresh or dried, and are part of the culinary traditions of that region. Berry et al., (2011) from Lake Pátzcuaro and Zamora-Barrios et al., (2019) from Lake Zumpango, two eutrophic lakes with known presence of cyanobacterial blooms, reported high concentrations of MCYST’s in whole Chirostoma, and suggested a particularly high potential for human exposure to food-derived cyanotoxins. Another case of the relevance of studying different tissues for cyanotoxins accumulations is presented by Hauser-Davis et al., (2015). They studied the accumulation of MCYST’s in Nile tilapia in the chronically contaminated and eutrophic Jacarepaguá lagoon, Brazil, finding a greater concentration of MCYST’s in gonads than in liver. They suggested that this is of concern since this could signal potential reproductive problems in tilapia, which, as noted above, is an important product of aquaculture (Hauser-Davis et al., 2015). All the above information highlights the relevance of studying several types of tissues depending on research goals. For example, from an ecological point of view of trophic transfer in natural ecosystems, it could be important to study cyanotoxins contains in whole organisms, probably separating different tissues. From a human health risk perspective, it could be relevant to study only muscle, if people are only eating fish fillets, for example.

Table 2 Fish species included in studies of accumulation of cyanotoxins by commercial importance in Latin America. Countries where the studies were conducted and type of tissues analyzed for each fish species also included. References in table footnote. *indicates introduced species.

| Species | Tissues analyzed | Countries | References |

| Commercial importance | |||

| Astyanax caballeroi (Contreras-Balderas & Rivera-Teillery 1985) | muscle | Mexico | 1 |

| Chirostoma jordani Woolman 1894 | whole fish | Mexico | 2 |

| Chirostoma sp. | Whole fish | Mexico | 3 |

| Coptodon rendalli (Boulenger 1897)* | liver, muscle, viscera | Brazil | 4,5 |

| Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus 1758* | liver, muscle | Mexico | 3 |

| Geophagus brasiliensis (Quoy & Gaimard 1824) | muscle | Brazil | 6,7,8,19 |

| Goodea sp. | viscera, muscle | Mexico | 3 |

| Hoplias sp. | muscle | Uruguay | 9 |

| Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Valenciennes 1844)* | liver, muscle | Brazil | 10 |

| Mayaheros urophthalmus (Günther 1862) | muscle | Mexico | 1 |

| Odontesthes bonariensis (Valenciennes 1835) | liver, gills, brain, intestine, muscle | Argentina | 11, 12 |

| Oreochromis aureus (Steindachner 1864)* | muscle | Mexico | 1 |

| Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus 1758)* | liver, muscle, gills, intestine, gonads, bile | Brazil, Mexico | 5, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 |

| Plagioscion squamosissimus (Heckel 1840)* | liver | Brazil | 10 |

| Rhamdia sp. | muscle | Mexico | 1 |

| Vieja fenestrata (Günther 1860) | muscle | Mexico | 1 |

| Vieja sp. | muscle | Mexico | 1 |

| No commercial importance | |||

| Dorosoma petenense (Günther 1867) | muscle | Mexico | 1 |

| Pseudoxiphophorus jonesii(Günther 1874) | muscle | Mexico | 1 |

| Thorichthys helleri(Steindachner 1864) | muscle | Mexico | 1 |

1Berry et al., 2012, 2Zamora-Barrios et al., 2019, 3Berry et al., 2011, 4Magalhães et al., 2001, 5Deblois et al., 2008, 6Clemente et al., 2010, 7Calado et al., 2017, 8Calado et al., 2019, 9Morandi 2015, 10Oliveira et al., 2013, 11Cazenave et al., 2005, 12Amé et al., 2010, 13Chellappa et al., 2008, 14Galvao et al., 2009, 15Vasconcelos et al., 2013, 16Hauser-Davis et al., 2015, 17Mendes et al., 2016, 18Lopes et al., 2020, 19Calado et al., 2018.

Fish trophic habits may potentially influence the accumulation of cyanotoxins (Zhang et al., 2009, Flores et al., 2018). For example, fish that feed on cyanobacteria that produce toxins have a direct path of cyanotoxin exposure (i.e., planktivorous fish), which is not present in piscivores or omnivorous fish. Two studies in the database deal with this topic in Latin America. Berry et al., (2011) analyzed the concentration of MCYST’s in three fish species of different trophic habits in Lake Patzcuaro: the mainly phytoplanktivorous Goodea sp., the zooplanktivorous Chirostoma sp. and the omnivorous Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus 1758. All three species accumulated MCYST’s, and its content correlated with fish trophic level, with concentrations of cyanotoxin measured as phytoplanktivorous > omnivorous > zooplanktivorous. The authors suggest that, although phytoplanktivorous zooplankton could be a source of MCYST’s for the fish, and could increase the exposure for zooplanktivorous fish, the microfauna of the lake is characterized by species that are not efficient grazers on cyanobacteria. Also, Berry et al., (2011) indicated that the accumulation of the cyanotoxin may be mainly associated with direct consumption of the cyanobacteria rather than to biomagnification to higher trophic levels. On the other side, Zamora-Barrios et al., (2019) found a higher concentration of MCYST’s in the zooplanktivorous Chirostoma jordani Woolman 1894 than in the omnivorous Nile tilapia (even liver) in Lake Zumpango. Indeed, future studies should specifically test the hypothesis of a relation between the trophic habit of fish and the accumulation of several cyanotoxins.

Fluctuations in bioaccumulation and depuration of cyanotoxins. Patterns of temporal changes of cyanotoxins bioaccumulation in the field have been analyzed in seven studies in Latin America focusing on MCYST (Magalhães et al., 2001, Cazenave et al., 2005, Amé et al., 2010, Oliveira et al., 2013, Zamora-Barrios et al., 2019) and STX’s (Clemente et al., 2010, Calado et al., 2017). Among them, some studies compared the accumulation of cyanotoxins in fish tissues between dry and wet season, however, although there were differences, there was not an obvious pattern of accumulation associated with a particular season. For example, Ame et al., (2010) found accumulation of MCYST’s in muscle of Odontesthes bonariensis (Valenciennes 1835) during both wet and dry season. The authors found temporal changes in the concentrations of MCYST variants (MCYST-LR, -RR, -LA and -YR), and suggested the need for an intensive monitoring program in that lake to ensure the health of people living in its surrounding. Also in O. bonariensis, Cazenave et al., (2005) found a higher concentration of MCYST’s in wet season in muscle, liver and gills, while Zamora-Barrios et al., (2019) sampled Nile tilapia in three sampling dates and C. jordani in six, finding a higher concentration of MCYST’s in tissues after the rains in both species when the decomposition of the Microcystis bloom occurred. Another study (Morandi 2015) suggested temporal fluctuations in MCYST’s accumulation, since toxin presence and cyanobacterial blooms were previously reported at the Reservoir Rincón del Bonete in Uruguay. However intense sampling in the muscle of Hoplias sp. found no toxins, highlighting the importance of sampling in different seasons. Contrastingly, Calado et al., (2017) did not find differences in the concentrations of STX’s between dry and wet season, and, Clemente et al., (2010) reported no significant difference in the STX’s concentrations in muscle among the three samplings seasons (summer, spring, autumn), both studies carried out in Alagados Reservoir, Brazil with Geophagus brasiliensis (Quoy & Gaimard 1824).

Two studies included a long sampling period: Magalhães et al., (2001) sampled the accumulation of MCYST’s in tissues of Coptodon rendalli (Boulenger 1897) for 40 months and Oliveira et al., (2013) determined the accumulation of MCYST’s in the phytoplanktivorous fish Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Valenciennes 1844) during one year. Sampling in both studies was every two weeks. Six distinct phases based on MCYST’s accumulations in different tissues were identified in Magalhães et al., (2001). Although MCYST’s were not detected in viscera and liver in some phases, they were always detected in muscle, with different concentrations of MCYST’s depending on the phase (Magalhães et al., 2001). For H. molitrix,Oliveira et al., (2013) found that during the drought months (April-September), the concentrations of toxins in muscle and liver were higher than in other months of the study period.

In general, the studies summarized here concerning fluctuations of cyanotoxins accumulation could reflect variations associated with type of cyanotoxin, accumulating species and/or geographic zone, which could be addressed in future analyses. Also, they highlight the need of site-specific studies of fluctuations of cyanotoxins accumulation in fish for a better understanding of potential human exposure by consumption of fish during annual changes in weather patterns.

Four studies analyzed the depuration of cyanotoxins (i.e., reduction or elimination of cyanotoxins after stop exposure during a specific time), finding contrasting results. First, Galvao et al., (2009) analyzed in Nile tilapia from an artificial lake in Brazil the presence of MCYST’s and STX’s, NOD, ATX’s and CYN’s, and its depuration. Only STX variants were detected in fish from the lake and, after a depuration time of five days without food in clean running water, the fish completely eliminated the STX’s in muscle and liver (Galvao et al., 2009). The authors suggested that depuration is a simple process that can be readily adopted by Nile tilapia producers as a way to eliminate STX’s. In contrast, Calado et al., (2017, 2019) analyzed the depuration of STX’s in G. brasiliensis from Alagados Reservoir, Brazil, during 40 and 90 days respectively, finding that although there was a reduction of STX’s in depurated fish, toxins were still present in fish muscle. Calado et al., (2017) found a reduction in the percentage of specimens with the STX variant in the depurated fish, while the concentrations of the gonyautoxin 2 (GTX2) variant increased. They suggested that STX variant could be transformed to GTX2 and such transformation may decrease the toxicity of cyanotoxins to fish, since GTX2 is less toxic than STX. In addition, Calado et al., (2019) determined the concentrations of STX’s in the water and fish feces during the depuration time, suggesting that the fish biotransformed and eliminated STX’s during the detoxification process and that the elimination of these toxins is possible but it takes a long time. Finally, Calado et al., (2018) studied the depuration of MCYST’s in G. brasiliensis during 90 days from Iraí Reservoir, Brazil. They found that MCYST’s concentrations increased in fish muscles during the depuration time at around 30 days, then MCYST’s decreased but were still present in fish muscle at 90 days when the experiment finished. Calado et al., (2018) argued that when MCYST’s enter into cells they can be bound to phosphatase proteins and glutathione (GSH), and, during the depuration process, the toxins were metabolized and released. Thus, they initially increased in fish muscles, and finally MCYST’s were excreted via feces and urine.

Future studies should focus on depuration patterns of other species and cyanotoxins, in order to determine the utility of the depuration process in reducing the exposure to humans when consuming fish exposed to cyanotoxins. Also, the suggested pattern of depuration of cyanotoxins by aquatic organisms in the field is promissory. It provides an option for species in natural environments to recover after a potential change in conditions of the waterbodies (e.g., after a management program to stop or reduce the eutrophication caused by human activities).

Potential human intake of cyanotoxins in Latin America. Several routes of human exposure have been recognized from water bodies containing cyanotoxins: use of drinking water, skin or nasal mucous membrane contact during recreational activities (e.g., swimming, canoeing or bathing), consumption of irrigated vegetables or fruits, consumption of aquatic organisms including fish, oral intake of cyanobacterial dietary supplements and dialysis (Drobac et al., 2013, Ibelings et al., 2021). In the case of the present review related to accumulation of cyanotoxins in freshwater organisms with some of them used as food, a tolerable daily intake (TDI) for lifetime has been recommended as a provisional guideline value for human consumption of contaminated organisms based on body weight (bw). For MCYST’s the recommended TDI is 0.04 µg/kg bw by World Health Organization (WHO) (Falconer et al. 1999), and for CYN’s of 0.03 µg/kg bw (Humpage & Falconer, 2003, Ibelings & Chorus, 2007). Also an acute reference dose (ARfD) of 0.5 μg STX’s equivalents/kg bw by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA, 2009) associated to the no-observed- adverse-effect level (NOAEL). In addition for MCYST’s, Ibelings & Chorus (2007) calculated 2.5 µg/kg bw for the maximum tolerable intake to avoid an acute exposure (ATI) by a single consumption and 0.4 µg/kg bw for short term exposure tolerable intakes (STI), for example during a cyanobacterial bloom.

As noted in Section 3.1.1 above, almost all the Latin America studies of bioaccumulation of cyanotoxins showed limitations and flaws in the analytical methods employed, precluding a reliable risk assessment due to the consumption of contaminated fish based on these studies. However, in a screening sense and to alert to the risk of cyanotoxins through food in the region, we calculated potential human intakes for studies in the database which reported potential daily intakes and compared them with some guideline values.

We recalculated the potential human intake of cyanotoxins by assuming an adult to weigh 70 kg, consuming 300 g of fish (muscle or whole fish as usually eaten) and for a child weighing 30 kg and consuming 200 g of fish. We compared the potential intake values calculated from field studies with TDI, STI and ATI thresholds. When studies reported concentrations in tissues by sample points in a waterbody, several seasons, or different fish stages, we calculated the intake considering the higher concentrations reported. When reported several water bodies in a study for the same species, we calculated the daily intake for each water body.

Based on the only study reporting accumulation of CYN’s in fish species in Latin America (Berry et al., 2012), no CYN’s concentration in muscle of the nine species reported from Catemaco Lake, México exceeded the TDI suggested (Humpage & Falconer, 2003; Ibelings & Chorus, 2007) (Table 3). For STX’s, four studies (including a total of 10 species) reported intake calculations (Table 3), however, only Calado et al., (2017) included concentrations in tissues exceeding the ARfD for G. brasiliensis from Alagados Reservoir, Brazil for both adult and child intake (exceeding 1.6 and 2.5-fold respectively).

Table 3 CYN’s and STX’s concentration (µg/kg) in muscle of different fish species by water body in Latin America including the corresponding daily intake by an adult and child (µg/kg body weight). Adult intake calculated based on consuming 300g by an 70kg body weight (bw) person and child intake based on consuming 200g by an 30kg bw person. Intake in bold exceed the ARfD of 0.5 µg/kg bw for STX’s equivalents (EFSA, 2009). *denotes the use of reliable analytical methods.

| Cyanotoxin/Fish species | Water body | Toxin conc. (µg/kg) | Daily intake adult (µg/kg bw) | Daily intake child (µg/kg bw) | Reference |

| CYN’s | |||||

| Astyanax caballeroi (Contreras-Balderas & Rivera-Teillery 1985) | 0.81 | 0.003 | 0.005 | ||

| Thorichthys helleri (Steindachner 1864) | 0.15 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Mayaheros urophthalmus (Günther 1862) | 0.26 | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Dorosoma petenense (Günther 1867) | 0.8 | 0.003 | 0.005 | ||

| Pseudoxiphophorus jonesii(Günther 1874) | Catemaco Lake, México | 1.26 | 0.005 | 0.008 | Berry et al., 2012 |

| Oreochromis aureus (Steindachner 1864) | 0.09 | 0.0004 | 0.001 | ||

| Rhamdia sp. | 0.24 | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Vieja fenestrata (Günther 1860) | 0.81 | 0.003 | 0.005 | ||

| Vieja sp. | 0.42 | 0.002 | 0.003 | ||

| STX’s | |||||

| Geophagus brasiliensis (Quoy & Gaimard 1824) | Alagados Reservoir, Brazil | 48 | 0.206 | 0.320 | Calado et al., 2017 |

| 187.3 | 0.803 | 1.249 | Calado et al., 2019* | ||

| 12.2 | 0.052 | 0.081 | Clemente et al., 2010 | ||

| Astyanax caballeroi (Contreras-Balderas & Rivera-Teillery 1985) | 0.71 | 0.003 | 0.005 | ||

| Thorichthys helleri (Steindachner 1864) | 0.06 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | ||

| Mayaheros urophthalmus (Günther 1862) | 0.32 | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Dorosoma petenense (Günther 1867) | 0.33 | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Pseudoxiphophorus jonesii(Günther 1874) | Catemaco Lake, México | 0.36 | 0.002 | 0.002 | Berry et al., 2012 |

| Oreochromis aureus (Steindachner 1864) | 0.03 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||

| Rhamdia sp. | 0.1 | 0.0004 | 0.001 | ||

| Vieja fenestrata (Günther 1860) | 0.3 | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Vieja sp. | 0.22 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Studies reporting intakes of MCYST’s included 10 species in several waterbodies from Brazil, Mexico and Argentina (Table 4). From all these countries, some studies reported fish intakes exceeding TDI, some even exceeding STI and ATI. In Argentina, Cazenave et al., (2005) reported potential intakes of MCYST’s due to consumption of O. bonariensis from San Roque Reservoir to be higher than TDI, while for the same species from Los Padres Lake, Amé et al., (2010) found intakes lower than TDI (Table 4). Most of the studies, including potential human intakes of MCYST’s, come from Brazil for four species and 18 water bodies (Table 4). Among them, Oliveira et al., (2013) reported the highest concentrations in muscle and, consequently, the highest daily intakes for a fish (H. molitrix) in Latin America, which exceed by 168 and 261-fold the TDI respectively for adult and child. In this case, the intake also exceeded the ATI, and represented a potentially high risk of intoxication by consumption of this planktivorous species. Contradictingly, H. molitrix was introduced in Paranoá Lake as an attempt to reduce the amount of cyanobacteria, and became an important issue of health risks for its consumption by local people (Oliveira et al., 2013).

Table 4 MCYST’s concentration (µg/kg) in muscle of different fish species by country and water body in Latin America, including the corresponding daily intake by an adult and child (µg/kg of body weight). Adult intake calculated based on consuming 300 g by a 70 kg body weight (bw) person and child intake based on consuming 200 g by a 30 kg bw person. Intakes in bold exceed the TDI of 0.04 µg/kg bw for a lifetime suggested by the World Health Organization (Falconer et al. 1999). (All concentration for muscle except for Chirostoma jordani and Chirostoma sp., which includes the whole fish). *Denotes the use of reliable analytical methods, aExceed the “short-term” daily intake of 0.4 µg/kg bw, bExceded maximum tolerable intake to avoid an acute exposure by a single consumption of 2.5 µg/kg bw.

| Country/Species | Water body | Toxin conc. (µg/kg) | Daily intake adult (µg/kg bw) | Daily intake child (µg/kg bw) | Reference |

| Argentina | |||||

| Odontesthes bonariensis (Valenciennes 1835) | Los Padres Lake | 4.9 | 0.021 | 0.033 | Amé et al., 2010* |

| San Roque Reservoir | 50 | 0.214 | 0.333 | Cazenave et al., 2005* | |

| Brazil | |||||

| Coptodon rendalli (Boulenger 1897) | Furnas Reservoir | 1.7 | 0.007 | 0.011 | DeBlois et al., 2008 |

| The Jacarepaguá lagoon | 337.3 | 1.44a | 2.24a | Magalhães et al., 2001 | |

| Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Valenciennes 1844) | Paranoá Lake | 1570 | 6.72b | 10.46b | Oliveira et al., 2013 |

| Geophagus brasiliensis (Quoy & Gaimard 1824) | Iraí Reservoir | 4.6 | 0.01 | 0.03 | Calado et al., 2018 |

| Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus 1758) | Acauã Reservoir | 0.006 | <0.002 | <0.002 | Mendes et al., 2006 |

| Acauã Reservoir | 0.37 | <0.002 | 0.002 | Vasconcelos et al., 2013 | |

| Araçagi Reservoir | 0.019 | <0.002 | <0.002 | Mendes et al., 2006 | |

| Aracoiaba pond | 570 | 2.44a | 3.8b | Lopes et al., 2020 | |

| Boqueirão do Casi Reservoir | 0.018 | <0.002 | <0.002 | Mendes et al., 2006 | |

| Cacimba de Varzea Reservoir | 0.03 | <0.002 | <0.002 | Mendes et al., 2006 | |

| Camalau Reservoir | 0.16 | <0.002 | <0.002 | Vasconcelos et al., 2013 | |

| Castanhão pond | 1040 | 4.45b | 6.93b | Lopes et al., 2020 | |

| Cordeiro Reservoir | 0.005 | <0.002 | <0.002 | Mendes et al., 2006 | |

| Cordeiro Reservoir | 0.23 | <0.002 | <0.002 | Vasconcelos et al., 2013 | |

| Funil Reservoir | 6.1 | 0.026 | 0.041 | DeBlois et al., 2008 | |

| Furnas Reservoir | 11.7 | 0.05 | 0.078 | DeBlois et al., 2008 | |

| Furnas Reservoir | 710 | 3.04b | 4.73b | Lopes et al., 2020 | |

| Ilha Solteira Reservoir | 350 | 1.5a | 2.33a | Lopes et al., 2020 | |

| Juara lake | 625 | 2.67b | 4.16b | Lopes et al., 2020 | |

| Linhares lake | 740 | 3.17b | 4.93b | Lopes et al., 2020 | |

| Orós pond | 655 | 2.81b | 4.36b | Lopes et al., 2020 | |

| The Jacarepaguá lagoon | 2.75 | 0.011 | 0.018 | Hauser-Davis et al., 2015 | |

| Tres Marias Reservoir | 780 | 3.34b | 5.2b | Lopes et al., 2020 | |

| México | |||||

| Chirostoma jordani Woolman 1894 | Zumpango Lake | 7 | 0.03 | 0.046 | Zamora-Barrios et al., 2019 |

| Chirostoma sp. | Pátzcuaro Lake | 18.5 | 0.079 | 0.123 | Berry et al., 2011 |

| Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus 1758 | Pátzcuaro Lake | 4.99 | 0.021 | 0.033 | Berry et al., 2011 |

| Goodea sp. | Pátzcuaro Lake | 157 | 0.67a | 1.047a | Berry et al., 2011 |

| Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus 1758) | Zumpango Lake | 2 | 0.008 | 0.013 | Zamora-Barrios et al., 2019 |

The MCYST’s intakes by consumption of Nile tilapia were reported in 19 cases (18 from Brazil), and in 10 of them exceeded the TDI (Table 4). Moreover, it is notably the study of Lopes et al., (2020) where the MCYST’s intakes of Nile tilapia from eight water bodies exceeded even the ATI. From Mexico, the MCYST’s intake by consumption of Goodea sp. and Chirostoma sp. from Pátzcuaro lake (Berry et al., 2011) and by C. jordani from Zumpango lake (Zamora-Barrios et al., 2019) exceeded the TDI (also the STI for Goodea sp.). Related to differences between adult and child intakes, two studies including Nile tilapia from Brazil (DeBlois et al., 2008) and C. jordani (Zamora-Barrios et al., 2019) from Mexico showed intakes exceeding TDI for child but not exceeding for adults, highlighting the higher risk to children of exposure to harmful levels.

Similar to the summarized data reported by Ibelings and Chorus (2007) on their review of accumulation of cyanotoxins in freshwater seafood and its consequences for public health, there are variations in cyanotoxins intakes depending on fish species and water body, in many cases exceeding the TDI, and some doses exceeding ATI. For example, Deblois et al., (2010) found intakes exceeding TDI for Nile tilapia, but lower (and not exceeding TDI) for C. rendalli in Furnas Reservoir, suggesting that certain fish known to feed on cyanobacteria might be safer for consumption than others, which could be considered in the formulation of public health guidelines. Indeed, more research is needed in order to evaluate the health problems for people consuming exposed fish on a local scale and for particular waterbodies, and its correlation to the provisional guideline values suggested. Also, specific factors of water bodies and consuming habits of people including the frequency and for which time spans people will be exposed by their diet, the duration of cyanotoxins occurrence in the water bodies where people get the fish, and other exposure routes acting synergistically, together with other risk conditions of expose people (i.e., health condition, age), will influence the potential risk for humans (Ibelings and Chorus 2007). Finally, reliable analytical methods for cyanotoxins concentrations in tissues of expose organisms should be implemented in future assessment of risk to human health in Latin America, even more considering the summarized patterns of risk in some cases using screening methods.

Future directions. The bioaccumulation of cyanotoxins and potential impacts on environment and human health constitute a complex scenario, where biological processes, but also social, economic, cultural, management, conservation and regulatory factors are involved. Some of these factors are out of the scope of the present review, however, we identified some future directions in order to reduce specifically for Latin America the potential harmful effects of cyanotoxin on the environment and humans.

As highlighted in the present review, bioaccumulation of cyanotoxins have been accessed only in four countries in Latin America, a region comprising ~20 countries and investigations have focused mainly on MCYST’s, for example, bioaccumulation of CYN’s and NOD have only been analyzed twice and once from México and Argentina, respectively. Accordingly, Zurawell et al., (2005) and Scarlet et al., (2020) stated that some cyanobacterial toxins, including CYN’s, are not routinely monitored around the world, and thus the range of toxins concentrations in natural systems is not known. There is a need for studies of bioaccumulation and monitoring, including less studied cyanotoxins and in more water bodies in more countries in Latin America, for a better understanding of potential risk of exposure to cyanotoxins. Aquaculture is a common activity in the region (Morales & Morales, 2006) and, as reported in the studies analyzed here, 80% of the species showing accumulation of cyanotoxins have commercial importance. To what extent the aquaculture constitutes an important route of transfer of cyanotoxins to humans is still unknown, and it should be determined in future studies. Also, as noted by Cantoral Uriza et al., (2017), it is important to investigate unknown cyanobacteria species from tropical areas in Latin America to access their potential toxicity.

From an ecological point of view, there is evidence of behavioral alterations caused by cyanotoxins exposure in fish (Malbrouck & Kestemont 2006), including a decrease in locomotor activity and altered reproductive behavior (reduction in the spawning activity and success) (Baganz et al., 1998). It is still unknown how changes in behavior associated with cyanotoxins exposure may affect fish populations in the wild (e.g., increasing or decreasing populations) and future studies could focus on the potential threat to conservation of native species by cyanotoxin exposure. Also, the trophic transfer of cyanotoxins has been widely documented (Ferrão-Filho & Kozlowsky-Suzuki et al., 2011, Lance et al., 2014), however, comprehensive analyses of food-chain effects of cyanotoxins (Zurawell et al., 2005) and potential negative impacts in a wide range of organisms (i.e., insects, other vertebrates than fish) in freshwater natural systems have not been evaluated and constitute a pending area of research in Latin America. In this sense, the implementation of new approaches, including ecotoxicological signals using omics analyses, allowing the investigation of thousands of molecular responses of the cell to cyanotoxins at the same time (Marie 2020), will be particularly useful in future studies.

The present review summarized the current knowledge of cyanotoxins accumulation in freshwater organisms in Latin America, integrating information of major topics studied in the region, including groups and species accumulating cyanotoxins, fluctuations and depuration of cyanotoxins, and potential human intake of cyanotoxins from field studies. A further understanding and reduction of the harmful effects of cyanotoxins on the environment and on human health, specifically for Latin America, is a promising field for future research. Additionally, in the face of the population increase and watershed modifications in the region, combined with climate change and eutrophication that promotes cyanobacterial blooms, the study and monitoring of bioaccumulation of cyanotoxins should be mandatory. Also, assessing, monitoring and/or managing cyanobacterial/cyanotoxins risks in water-use systems is lacking for most of the countries in the region. This scenario indicates the need for more efforts to generate scientific research, but also, this research needs to be linked with national and local level management policies.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)