Introduction

The presence of degraded soils is increasing worldwide and their restoration must be part of the strategies to meet the challenges brought about by global change (Lal, 2004; Bigas, Gudbrandsson, Montanarella and Arnalds, 2007). However, even though the importance of restoration of degraded sites has been recognized for some time (Bradshaw and Chadwick, 1980), in many scenarios the requisite knowledge to undertake restoration has not yet been acquired in an efficient, economical and socially acceptable manner. Soil erosion is a severe form of physical degradation. There are estimates placing moderate to severe degradation of agricultural land worldwide at 80% (Lal and Stewart, 1995). It is well known that plants control erosion by acting as a barrier to the impact of rain and the force of winds, while favoring infiltration and reducing runoff, thus preventing soil loss, and, in severe cases, gully formation. Once the soil has degraded and gullies have formed, complex measures are required to stop even further degradation, and recovery can take several decades (Mongil-Manso, Navarro-Hevia, Diaz-Gutierrez, Cruz-Alonso and Ramos-Diez, 2016). For example, Morgan (1986) suggests that a multiple-strata revegetation process is required using grasses, legumes, shrubs and trees around gullies to stop their expansion. Nevertheless, this approach does not solve the problem of establishing plant cover on the slopes of the gullies themselves.

Mycorrhizal fungi are of particular importance for the recovery of soil structure and dynamics. These fungi play a key role in the establishment and development of most plants (Colpaert, Tichele, Assche and Laere, 1999; Allen, Swenson, Querejeta, Egerton-Warburton and Treseder, 2003). Among the multiple benefits attributed to mycorrhization, its effect on plant development stands out, since there is widespread proof that mycorrhizas improve plant growth by increasing the absorption surface of the root system (Smith and Read, 1997), selectively absorbing and storing certain nutrients (Colpaert et. al., 1999), solubilizing certain chemicals and making some chemical elements that are normally insoluble, in particular phosphorus, available for the plant (Casarin, Plassard, Hinsinger and Arvieu, 2004; Liu, Loganathan, Hedley and Skinner, 2004). There are plants capable of forming simultaneous symbiotic associations with both arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and ectomycorrhizal fungi, which may contribute to improved environmental restoration strategies (Gómez-Romero et al., 2012; Gómez-Romero, Villegas, Sáenz-Romero and Lindig-Cisneros, 2013)

Ashes (Fraxinus spp.) are able to establish themselves on degraded sites to the extent that at least one species of the genus has turned into an invasive species by its introduction into areas outside its distribution range (Mulla et al., 2014). Nevertheless, some native species can be a good choice for revegetation of gullies within its natural distribution ranges, since the species of this genus are resistant to stress conditions caused by soils that are poor in nutrients and organic matter (Francis, 1990; Stabler, Martin and Stutz, 2001), and this may be the case of F. uhdei (Wenz.) Lingelsh. This is a species found in Mexico and Central America that is capable of forming symbiotic associations with both endo and ectomycorrhizas (Ambriz, Báez-Pérez, Sánchez-Yáñez, Moutoglis and Villegas, 2010), and previous experiments have shown that urea has a significant effect on the development of the external mycelium of the Pisolithus tinctorius ectomycorrhizal fungus associated with this host plant (Báez-Pérez, Sánchez and Villegas, 2010). For other species of this genus, it has been suggested that success in the establishment in degraded areas may be result of their capability in forming symbiotic associations with mycorrhizal fungi (Stabler et al., 2001 ).

In a preliminary controlled experiment in large containers (Báez-Pérez et al., 2015), filled with substrate obtained from gullies, suggested the potential of inoculated F. uhdei plants for restoration of gullies formed in Acrisols but the field test was lacking. In fact, there are very few articles that address the contribution of the Fraxinus-mycorrhyzal fungi system to plant performance in substrata, under field conditions, that are unsuitable for normal plant development due to severe soil erosion processes.

Objectives

In order to explore the role of dual mycorrhization and urea fertilization on Fraxinus plants survival and growth in poor substrates, and also to contribute information on their usefulness in gully restoration, an experiment was conducted in which individuals of this species were inoculated with an endomycorrhyzal fungus, and ectomycorrhizal fungus and with both types of mycorrhizal fungi simultaneously, and urea fertilization.

Materials and methods

Seeds of Fraxinus uhdei were collected in the locality of Huertitas, Ejido de Atécuaro, Morelia, Michoacán (19° 33’ 05’’ and 19° 37’ 08’’ N and 101° 05’ 07’’ W; altitude 2275 m a.s.l.), where the experimental site is located. The area is mostly devoid of vegetation as a result of deforestation and agricultural practices unsuited for the fragile acrisol soils, which have led to the formation of deep gully systems. The area has a subhumid climate with rains in summer (July to October), with an average annual temperature of 14.8 °C and annual mean rainfall of 1000 mm (Duvert et al., 2010).

Plants of F. uhdei were propagated in a shade house (20%) in March 2012. The seeds were scarified manually and disinfected with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) at 10% (v:v) for 15 min. They were then planted in rigid plastic containers (375 cm3), using a perlite-peat moss substrate (2:1 v/v) that was autoclaved at 121 °C and 15 PSI during 30 min.

After 9 weeks, the plants were separated into four groups. Plants in the first group were not inoculated, and those in the other three groups were inoculated as follows: a) one group with the mycorrhizal fungus P. tinctorius (1 x 106 spores/plant) using micronized peat as a vehicle; b) a second one with the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus G. intraradices (50 spores/plant) applied as a suspension in distilled water; and c) the third one with a mixture of both fungal species (dual inoculation), each species applied as mentioned above. The P. tinctorius inoculum was acquired from Biosyneterra Solutions Inc. (L’Assomption, Québec, Canada), and G. intraradices was obtained from isolated cultures from the Laboratorio de Interacción Suelo-Planta-Microorganismo of the Instituto de Investigaciones Químico Biológicas de la Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo.

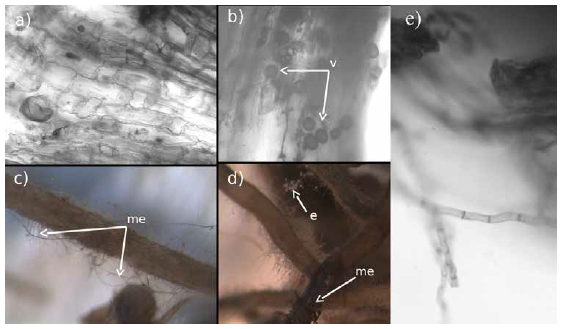

After 17 weeks had passed from inoculation, and before being taken to the field, 10 individual ash plants from each inoculation treatment were randomly selected to verify mycorrhization as follows. The arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus was identified using the ink and vinegar staining technique described by Vierhelig, Cougilan, Wyss and Piche (1998) by clarifying the roots with 10% KOH (w/v) for 30 min, to stain afterwards with Shaeffer black ink dissolved to 10% with 25% acetic acid, rinsing excess staining agent with running water. Once the roots had been stained, the characteristic structures of the species (arbuscules, vesicles and/or not-septated mycelium) were identified by taking photographs with a Leica DFC 295 (version 7.0.1.0) camera, using specialized software (Leica Application Suite Version 3.4.1). P. tinctorius was detected using a technique developed by Thompson, Grove, Malajczuk y Hardy (1993) modified by Ambriz et al. (2010), by staining the mantle and external mycelium of the fungus associated to the fine root segments of the ash with trypan blue at 0.05% for 24 h and then rinsing the dye with distilled water before observation through a microscope to identify the characteristic septated mycelium of this species.

The experimental plot had very little organic matter (0.78%), very low total available nitrogen (19.60 kg/ha) and phosphorus (0.347 mg/kg). The ash plants were distributed randomly, 14 replicas per treatment, on a westward-facing slope of a gully 6 m deep. Once planted, half of the plants of each inoculation treatment were fertilized with urea (NH2CONH2) dissolved in water at a concentration of 200 mM, each plant receiving 0.384 g of urea dissolved in 250 ml of water, once every 15 days during the rainy season (July to November). No watering took place during the dry season.

Due to the combination of inoculation and urea fertilization factors, the experiment consisted in an orthogonal design with eight treatments: 1) F. uhdei plants, 2) F. uhdei plants + urea, 3) F. uhdei plants + G. intraradices, 4) F. uhdei plants + G. intraradices + urea, 5) F. uhdei plants + P. tinctorius, 6) F. uhdei plants + P. tinctorius + urea, 7) F. uhdei plants +dual inoculation and 8) F. uhdei plants + dual inoculation + urea. The experiment was evaluated during 23 months, registering plant survival and measuring height on a monthly basis, diameter at base (DAB 1 cm from soil surface), cover (measured by the ellipse formula r1r2π with two radiuses for the crown) and number of leaves every six months.

Statistical analyses were carried out using generalized linear models followed by hypothesis testing with error II. A normal distribution was used for the analysis of all of the variables except the number of leaves, for which a Poisson-type distribution was used. Where one of the factors was not significant for a given variable, the factor was removed from the analysis, which allowed using the full data set in those cases (Crawley, 2007). All of the analyses were carried out using R (R Development Core Team, 2015).

Results

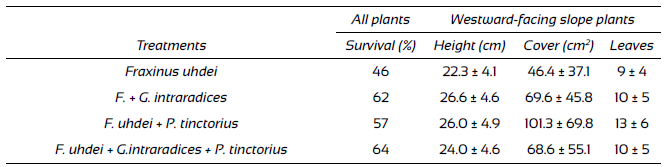

Root tissue preparations of the plants for the three inoculation treatments showed that all plants formed mycorrhizas with Glomus intraradices, Pisolithus tinctorius or with both fungus species simultaneously (Fig. 1). There were differences in survival due to the inoculation treatments. Greatest survival was observed in plants with dual inoculation (64%), followed by those inoculated with P. tinctorius (57%) and finally by those that were not inoculated (46%), regardless of fertilization. The significant differences among treatments (χ2 = 11.1; d.f. = 3; p = 0.01) were the result of the difference between the plants that received dual inoculation and control plants.

Figure 1 In (a) roots of Fraxinus uhdei from control plants with no evidence of mycorrhiza, in (b) roots with Glomus intraradices vescicles; in (c) roots with Pisolitus tinctorius external mycelium (me); in (d) spores of Glomus intraradices (e) and external mycelium of Pisolitus tinctorius (indicated by the arrows), in (e) septated hyphae of P. tinctorius.

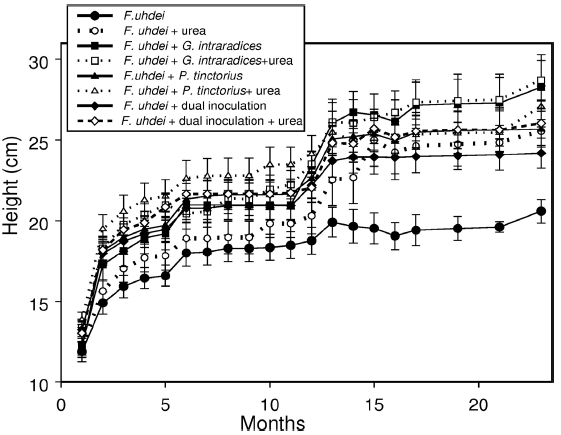

Plant growth started to show differences among treatments at the end of the first growing season (during the fourth and fifth months of evaluation) when mean values became noticeable different for some of the treatments, as reflected in changes in height (Fig. 2). However, differences started to be significant after 12 months (during the second growing season), in particular between the plants inoculated with G. intraradices, regardless of fertilization and non-inoculated control plants (Table 1). The data on the last evaluation showed that plants inoculated with G. intraradices were the tallest (26.6 cm ± 4.6 cm), followed by the plants inoculated with P. tinctorius (26.0 ± 4.9), then the plants with dual inoculation (24.0 cm ± 4.6 cm) and finally, non-inoculated plants (22.3 cm ± 4.1 cm). Differences attributable to this factor are significant (F(3,98) = 4.6, p = 0.005), since plants inoculated with any of the mycorrhigenic fungi were taller than those in the control group. The effect of fertilization was marginally significant (F(1,98) = 4.6, p = 0.03), since fertilized plants were only slightly taller (25.9 cm ± 5.0 cm) than non-inoculated plants (23.8 cm ± 4.5 cm), and there being no interaction between fertilization and inoculation.

Figure 2 Growth, as height, of Fraxinus uhdei during the lapse of the experiment. Growth occurred during the rainy seasons and the differences become evident after one year of planting.

Table 1 Performance parameters of Fraxinus uhdei plants at the end of the experiment in response to inoculation.

Survival is for all plant in both slopes (see text) and growth parameters are for the plants in the westward-facing slope where enough plants survived allowing statistical analyses. Data are means and standard deviations.

Cover also responded to inoculation treatments and followed a pattern similar to that for height, but the values for the plants inoculated with only one of the fungal species were inverted, since this variable was greater for plants inoculated with P. tinctorius(101.3 cm ± 69.8 cm), followed by those inoculated with G. intraradices (69.6 cm ± 45.8 cm), then plants with dual inoculation (68.6 cm ± 55.1 cm) and finally non-inoculated plants (46.4 cm ± 37.1 cm). The difference among inoculation treatments was significant (F(3,98) = 4.3, p = 0.007), and the effect of fertilization was not (F(1,98)= 3.6, p = 0.06). In regard to number of leaves, the highest values were observed for plants inoculated with P. tinctorius (13 ± 6), followed by plants with dual inoculation (10 ± 5), then those inoculated with G. intraradices (10 ± 5), and finally non-inoculated plants (9 ± 4). Differences among treatments were statistically significant (χ2 = 17.1; d.f. = 3; p = 0.0006), as a result of the difference between plants inoculated with G. intraradicesand control plants. The effect of fertilization on the number of leaves was marginal (χ2 = 6.2; d.f. = 1; p = 0.01). Plants fertilized with urea had more leaves (11 ± 6) than those that were not. Lastly, diameter at base was larger for the plants inoculated with P. tinctorius (0.94 ± 0.20), followed by those inoculated with G. intraradices (0.83 cm ± 0.18 cm), then those with dual inoculation (0.81 cm ± 0.20 cm), and finally non-inoculated plants (0.74 cm ± 0.17 cm). The difference between inoculation treatments was significant (F(3,98) = 4.9, p = 0.003), and the effect of fertilization was not (F(1,98) = 21; p = 0.15), and no interaction was detected between both experimental factors.

Discussion

The results of this experiment show that establishment of Fraxinus uhdei is possible in severely degraded sites where the substrate is no longer suitable for natural plant development. Although it has been documented that some of the species of this genus are tolerant to stress in sites that are unsuitable for other tree species (Francis, 1990; Stabler et al., 2001), conditions present at this study site were even more severe that those mentioned in such studies. In addition, this study provides information on the effects on the plant of multiple mycorrhizal interactions in scenarios of this type, in which some performance variables improve as a result of the interaction, as was the case for improved survival with the P. tinctorius, G. intraradices dual inoculation; whereas growth variables showed improved response to inoculation with only one of the fungi, height to inoculation with G. intraradices, and cover, number of leaves and diameter at base to inoculation with P. tinctorius.

The F. uhdei-G. intraradices-P. tinctorius interaction has not been studied in depth, and has only been addressed under controlled conditions in growth chambers (Ambriz et. al., 2010) or in mesocosms (Báez-Pérez et al., 2015) but never in the field, as in this study. Nevertheless, our results coincide with those found by Ambriz et. al. (2010), who first reported the symbiotic association with both species of mycorrhizal fungi and observed the synergic effect of dual inoculation on ash development when compared to single inoculation.

It is interesting to note that nitrogen fertilization had a marginal effect on survival and height of F. uhdei only, and had no effect on the remaining variables analyzed. As regards to growth, they were consistent with the results found by Canellas, Finat, Bachiller and Montero (1999); however, with respect to survival they were not, and the difference could be attributed to the conditions to which the plants were exposed in our experiment, given the extremely low level of nutrients in the substrate.

Conclusions

The experiment showed that the highest values obtained for the growth variables analyzed were those for inoculation with P. tinctorius, but not different from dual inoculation and statistical different when compared to inoculation with G. intraradices or the control (no inoculation), and this differs somewhat from the results of other works that show a synergy for growth variables in plants with dual inoculation (Founoune et. al., 2001; Misbahuzzaman and Newton, 2006; Ambriz et. al., 2010; Báez-Pérez et. al., 2015). It is possible for this difference to be the result of drought conditions during the dry season, because it has been shown that ectomycorrhizal fungi increase the ability of plants to resist drought stress through morphophysiological and biochemical mechanisms (Parke, Linerman and Black, 1983; Alvarez et al., 2009), although a more careful study in this regard is required. Finally, and given the improvements in survival of F. uhdei, in response to dual inoculation, our results suggest that in severely degraded soils, inoculation of this type may constitute an efficient strategy for environmental restoration.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)