Introduction

Hot springs can be found in many regions of the world. Each hot spring has unique geophysical and biological characteristics, making them interesting subjects of research with potential value for either biotechnological or ecological purposes (Briggs et al., 2014, Brock, 1997, Klatt et al., 2011; Lau, Aitchison, & Pointing, 2009; Tirawongsaroj et al., 2008). Because of these differences, bacterial diversity in microbial mats is expected to be different among hot springs. Analyses of microbial diversity have been reported for hot springs located in many countries, including the USA (Ward, Ferris, Nold, & Bateson, 1998), Russia (Perevalova et al., 2008), Australia (Kimura et al., 2005), Thailand (Portillo, Sirin, Kanoksilapatham, & González, 2009), Bulgaria (Tomova et al., 2010), Colombia (Bohorquez et al., 2012), Philippines (Huang et al., 2013), Chile (Mackenzie, Pedrós-Alió, & Díez, 2013) and China (Briggs et al., 2014).

The physicochemical parameters of source waters in some hot springs can vary by season while in others, these parameters can be very stable. These parameters can influence the microbial diversity in springs. A few studies have assessed these parameters in association with microbial community composition in hot springs (Briggs et al., 2014, Ferris and Ward, 1997, Mackenzie et al., 2013). For example, microbial diversity was surveyed in 3 hot springs located in La Patagonia, Chile, over 2 seasons. The authors found differences in the microbial communities between the seasons, probably due to temperature variations (Mackenzie et al., 2013). Other factors, such as pH, levels of hydrogen sulphide, and temperature, have been associated with the presence of certain microbial species (Briggs et al., 2014, Purcell et al., 2007, Ward and Castenholz, 2000).

To determine the bacterial diversity in microbial mats, both cultivation-dependent and -independent approaches have been employed, depending on the research goals. A cultivation-independent methodology was used in a recent PhyloChip microarray analysis of the microbial communities inhabiting hot springs of the Tengchong region in China (Briggs et al., 2014). However, this technology is not appropriate for the isolation of thermophilic microorganisms, their genes, or their proteins to determine their potential importance for biotechnology applications (Brock & Freeze, 1969). The 2 approaches can be complementary; however, an initial microbial diversity analysis can be a first step in searching for bacteria with enzymatic activities for industrial application. A good example of this approach is a report by Kanokratana, Chanapan, Pootanakit, and Eurwilaichitr (2004), which first described the biodiversity of bacteria and archaea from hot springs in Thailand. Years after this work, they reported on a functional screening of a metagenomic library derived from sediments of the hot springs, which resulted in the isolation of 2 novel genes encoding an esterase and a phospholipase (Tirawongsaroj et al., 2008).

In the present study, using a culture-dependent approach, we investigated the seasonal variation (Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter) in bacterial diversity of 2 hot springs located in the geothermal system of Araró, Michoacán, México, which is a system independent from Los Azufres geothermal zone (Brito et al., 2014, Viggiano-Guerra and Gutiérrez-Negrín, 2005). The physicochemical parameters of both hot springs were assessed and associated with fluctuations in bacterial biodiversity.

Materials and methods

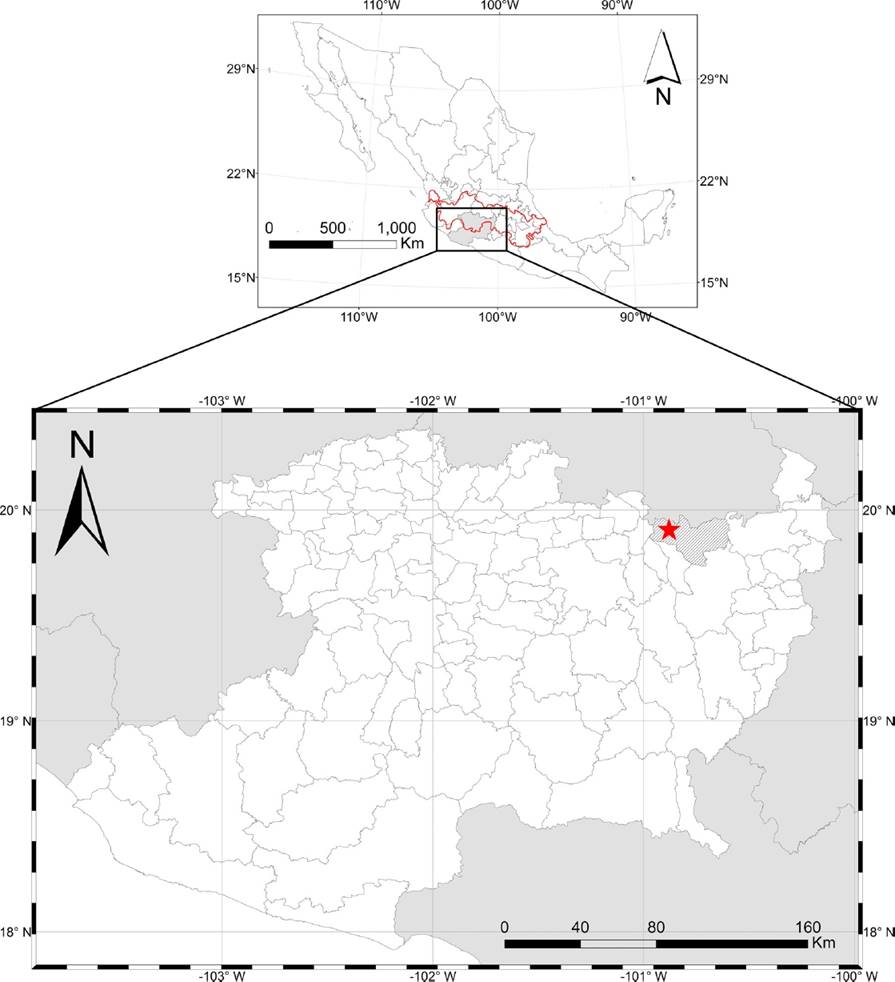

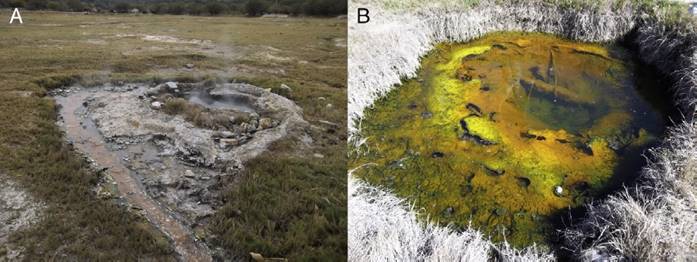

The geothermal system of the Araró region is located in the central part of Mexico, inside the Trans Mexican Volcanic Belt located in Michoacán State. The region is approximately 20 km west of the well-known Los Azufres geothermal field (Fig. 1). The zone known as Zimirao (19°53′54″ N, 100°49′50″ W) is where most of the hot springs are located. There are about 50 hot springs in the Araró region, and many of them are used for recreational activities; however, the selected hot springs, Tina and Bonita, have relatively little disturbance and are far from the recreational area. Another interesting feature of these hot springs is that Bonita has low water emission and forms colourful microbial mats, while Tina has a constant water effluent and a little running stream, with microbial mats formed along the stream (Fig. 2). Compared to Bonita, Tina presents only a very thin bacterial mat. Therefore, the systems exhibit different features that might influence the communities present in microbial mats.

Figure 1 A map that shows the location of the Araró, Michoacán, México (red star). The Araró hot springs are located within the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, approximately 20 km west from the well-known Los Azufres geothermal field.

Figure 2 A view of the 2 hot springs from Araró. On the left (A) is the so called Tina hot spring, with constant emission of water. Panel B shows a view of the Bonita hot spring, a “closed system” with low emission of water.

Four samplings were conducted on February 2nd (Winter), June 5th (Spring), October 6th (Summer), and December 5th (Fall) of 2013. Three samples were directly collected from microbial mats in each of the 2 hot springs at a depth of 30–50 cm from the surface. A criterion for selection of these 2 hot springs was whether the system was closed or open. One spring selected was a “closed system” with low water emission (Bonita), while the other (Tina) was an “open system” with constant water emission (Fig. 2). Microbial mat samples were immediately transported on wet ice to the lab. For water sampling, 500-mL sterile Kinex flasks were used to take water from each hot spring. Water samples were stored in darkness and transported to lab on dry ice.

Physicochemical parameters of water in the hot springs were measured during sampling of biological material. The parameters, including temperature (°C), electrical conductivity, pH, and dissolved oxygen, were measured in situ with a Corning® Checkmate™ II modular meter system.

Physicochemical analyses, including faecal coliforms analysis, were performed in collaboration with the National Water Commission (Conagua-México) (Table 1). Arsenic concentrations in the water samples of the Bonita and Tina hot springs were measured by absorption spectroscopy using an atomic absorption spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer Analyst 200) with a hydride generation system. The measurement of fluoride was carried out with a conventional fluormeter.

Table 1 Physicochemical parameters measured from Araró geothermal zone, Tina and Bonita hot springs, 4 seasons sampled.

| Hot spring | Season | T | pH | BOD | TS | EC | Cl | SO4 | A | Ca | Mg | Na | As |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tina | Winter | 63 | 7.35 | 0.8 | 2,423 | 3,860 | 977 | 246 | 330 | 188 | 25 | 625 | 4.9 |

| Spring | 66 | 7.64 | 0.6 | 3,722 | 3,840 | 960 | 245 | 338 | 207 | 28 | 581 | 4.7 | |

| Summer | 78 | 6.95 | 0.6 | 2,616 | 3,950 | 976 | 252 | 347 | 209 | 31 | 610 | 6.6 | |

| Autumn | 74 | 7.07 | 3.0 | 2,410 | 3,510 | 867 | 228 | 330 | 153 | 45 | 545 | 6.1 | |

| Bonita | Winter | 50 | 6.75 | 0.6 | 2,896 | 3,650 | 928 | 239 | 310 | 230 | 22 | 533 | 3.7 |

| Spring | 45 | 7.03 | 0.8 | 3,184 | 3,801 | 951 | 245 | 337 | 202 | 29 | 586 | 4 | |

| Summer | 50 | 7.49 | 0.4 | 2,398 | 3,670 | 917 | 237 | 328 | 187 | 32 | 569 | 2.9 | |

| Autumn | 55 | 7.78 | 2.6 | 2,502 | 3,650 | 910 | 239 | 328 | 158 | 48 | 567 | 2.7 | |

T, temperature (°C); BOD, biochemical oxygen demand (mg/l); TS, total solids*; EC, electrical conductivity (μmhos/cm); Cl, chloride salts*; SO4, sulphates*; A, alkanity*, Ca*, Mg*, Na*, As*; *reported as mg/L.

A small sample (0.1 g) of the microbial mat from each spring was placed into Eppendorf tubes (1.5 mL) with 990 μl of sterile water, vortexed, and plated onto 3 different 10-fold-diluted culture media. These included salted, rich, and poor media (Luria-Bertani, Nutrient Agar (NA), and Minimal Medium (MM), respectively, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich). The LB medium contained (/L) yeast extract (5 g), tryptone (10 g), NaCl (10 g). NA medium contained (/L) peptone (5 g) and beef extract (5 g). MM medium contained (/L) glucose (2 g), NaHPO4 (6 g), KH2PO4 (3 g), NaCl (0.5 g), NH4Cl (1 g), MgSO4 (0.5 g), CaCl (0.01 g), tyrosine (0.1 g) and agar (15 g). Most bacterial isolates (90%) grew well and were selected on LB media. Plates were incubated for 72 h at 37 °C and the number of colony forming units (CFU) was calculated per gram of microbial mat.

Randomly picked colonies were subject to further serial dilutions to obtain single isolates. Isolates were ON cultured in 3 ml of medium. Genomic DNA was isolated by following the protocol of the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit and subjected to PCR amplification of their 16S ribosomal subunit gene. Other bacterial isolates (105 from each hot spring) that exhibited an identical fingerprint by RAPDs analysis (Random Amplification of Polymorphic DNA) were assigned to the sequenced phylotypes to report presence/absence during the sampling seasons. The primer employed for the RAPD analysis was OPA02, 5′-TGC CGA GCT G-3′′ (Samal et al., 2003). Bacterial primers fD1, 5′-CAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′, and rD1, 5′-AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCC-3′, were used (Weisburg, Barns, Pelletier, & Lane, 1991) to amplify nearly full-length 16S ribosomal genes. PCR conditions have been previously reported (Hernández-León et al., 2015). All the PCR products were purified and sequenced at the LANGEBIO (Irapuato, Mexico). The 16S rDNA sequences obtained were subjected to homology blast searches against databases and deposited in GenBank (Accession Numbers: KJ801569–KJ801648).

Multiple sequence alignments were generated and a phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences was carried out using the MEGA 5.0 program (Tamura et al., 2011). All sequences passed quality controls and a cut-off value of 98% similarity was applied. To obtain a confidence value for the aligned sequence dataset, a bootstrap analysis of 1,000 replications was performed. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using a maximum likelihood algorithm.

Diversity indexes, including the Shannon (Shannon, 1948), evenness, and Simpson (Simpson, 1949) indexes, were calculated to infer species richness and abundance. Sørensen similarity index (Sørensen, 1948) was used to compare the similarity of the bacterial communities from Tina and Bonita microbial mats. Rarefaction curves were generated to evaluate sampling efforts. Pearson's coefficient with a 90% confidence value was used to determine significant positive relationships between diversity and any physicochemical parameters (PAST software).

Results

The physicochemical parameters of both hot springs are presented in Table 1. Bonita and Tina hot springs have different superficial temperatures. Bonita temperatures range from 45 °C to 55 °C throughout the year, while in Tina, they vary from 63 °C to 78 °C. A neutral pH was found in both hot springs, with little seasonal variation; however, greater variation was found in Bonita, with a pH range of 6.75–7.78, whereas in Tina it ranged from 6.95 to 7.64. Salt contents, including Ca, Cl, SO4, Mg, and Na, of the springs also showed variation across seasons and differences between hot springs. Interestingly, arsenic concentration varied little across seasons in each hot spring, but concentrations were much higher in Tina (4.7–6.6 mg/L) than in Bonita (2.7–4 mg/L). Conductivity values were slightly higher for Tina during Winter, Spring, and Summer. Faecal coliforms (NMP/100 m3) were not detected in either hot spring (data from Conagua).

In order to detect the abundance of culturable bacterial cells, the number of CFUs per gram of microbial mat was determined from each hot spring. In general, the number of CFUs was relatively low and fluctuated slightly across seasons. However, it was interesting to note that Bonita showed a 10-fold higher CFU count than the Tina hot spring (1 × 102 CFU/g and 1 × 103 CFU/g, respectively), regardless of the season.

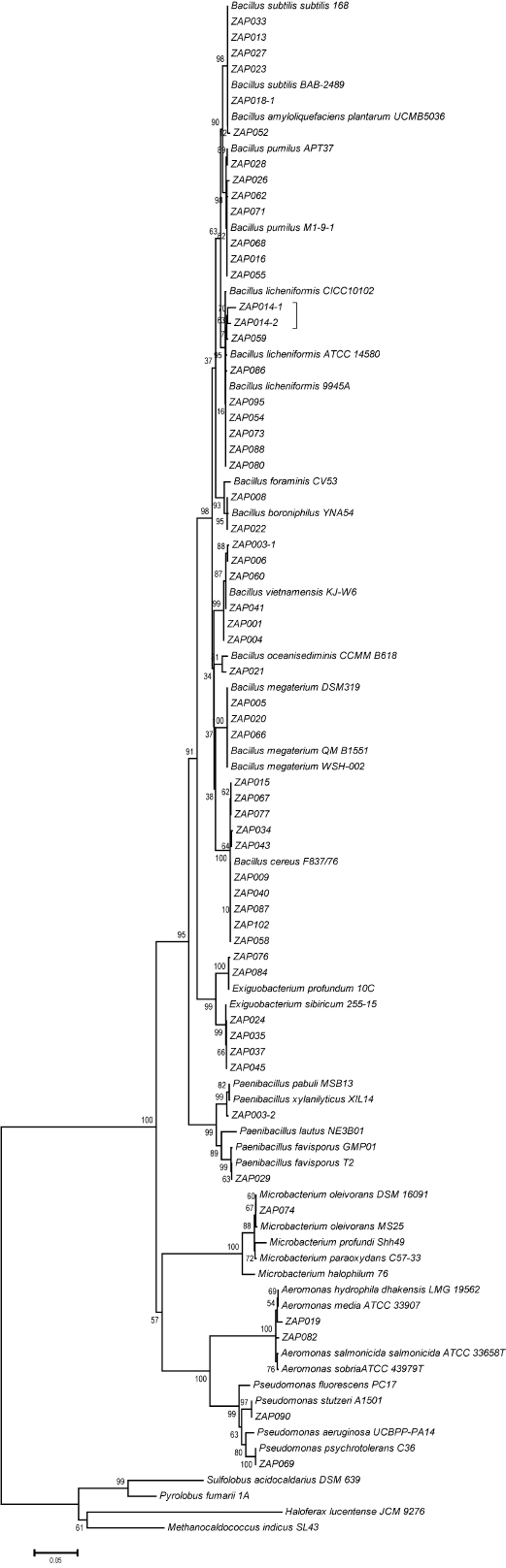

From randomly picked colonies subjected to RAPD analysis, 79 phylotypes (out of 109 bacterial isolates) were detected and subjected to 16S rDNA sequencing. Bacteria from 3 phyla were identified, including species from the genera Paenibacillus, Exiguobacterium, and Bacillus (76%) from the phylum Firmicutes, Aeromonas and Pseudomonas (18%) from the phylum Proteobacteria, and only Microbacterium (6%) from the phylum Actinobacteria. In total, 17 culturable bacterial species were detected in both hot springs. Figure 3 shows the phylogenetic relationships of the bacterial species. Fifty-seven 16S rDNA sequences, including the 17 representative bacterial species shared between both hot springs, were selected for the phylogenetic reconstruction based on length. All of the 16S rDNA sequences displayed close relationships with known bacterial species, particularly with representatives of the Bacillus genus. The clades were not associated with either of the hot springs or any other parameter measured.

Figure 3 Phylogenetic tree of the 79 phylotypes identified in both hot springs from Araró. Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequences was carried out with the MEGA 5.0 program. The tree was constructed by using the maximum likelihood algorithm with a bootstrap analysis of 1,000 replications.

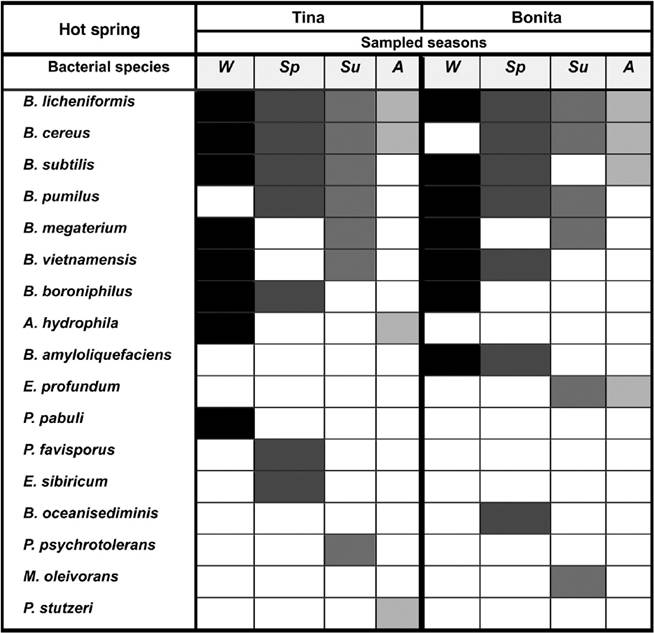

A dominant group of Bacillus was present in at least 3 out of 4 samplings and included the species Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus subtilis, and Bacillus pumilus (Fig. 4). The frequent species were Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus vietnamensis, Bacillus boroniphilus, Aeromonas hydrophila, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, and Exiguobacterium profundum, which appeared in 2 sampling seasons, while occasional bacterial species appeared only in 1 sampling and included Paenibacillus pabuli, Paenibacillus favisporus, Exiguobacterium sibiricum, Bacillus oceanisediminis, Pseudomonas psychrotolerans, Microbacterium oleivorans, and Pseudomonas stutzeri.

Figure 4 Occurrence of bacterial species isolated during the 4 seasons (Wi, winter; Sp, spring; Su, summer; Au, Autumn) of the year in the hot spring microbial mats from Araró, México. Bacterial species were classified as dominant (isolated in at least 3 out of 4 sampling seasons), frequent (isolated in 2 sampling seasons) and occasional (isolated only in one sampling season).

The bacterial communities of the microbial mats from Tina and Bonita hot springs were characterised by a few dominant taxa within the Firmicutes and by low abundance (Fig. 4). The Shannon index showed a similar low diversity of bacterial species for each hot spring in each of the 4 sampling seasons. The highest diversity was observed in the Spring and the lowest diversity was observed in the Fall for both Tina and Bonita. According to the Sørensen index, the 2 hot springs shared up to 64% of their bacterial species. However, this percentage varied, and in some seasons was much lower (Table 2). For example, during the Fall sampling, both springs shared only 16%, opposed to Spring, where they shared almost 50% of bacterial species.

Table 2 Ecological indexes for each sampling at Araró geothermal zone.

| Ecological indexes | Hot spring | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonita | Tina | |||||||

| Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn | |

| Shannon | 1.91 | 2.02 | 1.53 | 1.07 | 1.91 | 1.77 | 1.75 | 1.17 |

| Evenness | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.80 |

| Simpson | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.37 |

| Sorensena | 64% | |||||||

| Sorensenb | Winter 40% | Spring 48% | Summer 32% | Autumn 16% | ||||

a Sorensen bacterial community shared between Tina and Bonita.

b Sorensen bacterial communities shared each sampled season.

Pearson's correlation analysis suggested that water salts (such as Mg, Na, Cl), biological oxygen demand, and electrical conductivity all had effects on bacterial communities inhabiting Tina hot spring, whereas in Bonita, temperature, pH, and arsenic concentration exerted effects on bacterial diversity (Table 3). These results suggest that Tina and Bonita share some physical and biological features, but are not interconnected subsystems.

Table 3 Correlation between physicochemical parameters and bacterial fluctuations. In bold the higher correlations for each sampled site, Tina and Bonita.

| Physicochemical parameters | Pearson correlation coefficients | |

|---|---|---|

| Tina | Bonita | |

| Arsenic | 47.4 | 94.4 |

| Calcium | 82.3 | 87.9 |

| Chlorides | 97.9 | 87.0 |

| DBO | 95.4 | 78.9 |

| Electrical conductivity | 92.0 | 60.4 |

| Magnesium | 99.4 | 80.7 |

| pH | 42.5 | 91.7 |

| Sodium | 91.3 | 6.8 |

| Sulphates | 89.8 | 55.8 |

| Temperature | 50.1 | 90.5 |

| Total solids | 29.1 | 81.8 |

Discussion

The present study represents the first exploration of bacterial diversity in 2 of the approximately 50 hot springs located in Araró, Michoacán, which is in the middle of the Trans Mexican Volcanic Belt (Israde-Alcántara & Garduño-Monroy, 1999). Unfortunately, most thermal springs in Araró, and nearby regions, are used for recreational purposes and have been drastically modified, leaving the undisturbed ecosystems unexplored and likely reducing their microbiological diversity and biotechnological potential (López-Sandoval, Montejano, Carmona, Cantoral, & Becerra-Absalón, 2016). Therefore, there is a need for microbial censuses of the few hot springs in Araró that remain undisturbed.

Most recent publications on the biodiversity of microbial mats from hot springs around the world have described studies based on non-culture methods, including denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE), PhyloChip microarray, and sequencing of 16S rDNA gene libraries. Some of these studies have analysed the effect of seasonality and physicochemical parameters on microbial diversity (Briggs et al., 2014; Lacap, Barraquio, & Pointing, 2007; Mackenzie et al., 2013). Here, it was our short-term goal to describe the bacterial diversity in microbial mats by first isolating aerobic heterotrophic thermophilic bacteria. Our long-term goal, however, is to obtain easy-culturable bacterial isolates for bioremediation or biodegradation. Araró hot springs are extreme environments where bacteria with potential for biodegradation may reside. Our results suggest that bacteria belonging primarily to division Firmicutes occur there (Fig. 3). Interestingly, of the 13 species of Firmicutes isolated, only B. megaterium (Baker, Gaffar, Cowan, & Suharto, 2001), E. profundum (Crapart et al., 2007), and a strain of Paenibacillus (Mead et al., 2012) have been isolated from thermal environments. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the remaining species have been identified as inhabitants of hydrothermal systems. B. subtilis, B. cereus, B. licheniformis, B. pumilus, and B. megaterium are common soil inhabitants (Slepecky & Hemphill, 2006), although they have the capacity to grow at high temperatures (Slepecky & Hemphill, 2006; Yakimov, Timmis, Wray, & Fredrickson, 1995). The vast majority (> 90%) of the bacterial isolates from Tina and Bonita hot springs grew optimally at 50 °C (data not shown). Several studies have demonstrated that thermophilic bacilli, grown optimally above 40 °C, possess the potential to degrade or convert environmental pollutants (Margesin & Schinner, 2001). In addition, mat-forming cyanobacterial strains have shown synergistic effects in degrading petroleum compounds like phenanthrene, pristane, n-octadecane, and dibenzothiophene (Abed & Köster, 2005).

Another genus frequently isolated from Tina and Bonita hot springs was Exiguobacterium. Strains of this genus have been isolated from many different sources, including glacier ice, hot springs in Yellowstone National Park, as well as other extreme environments (Vishnivetskaya, Kathariou, & Tiedje, 2009). This genus comprises psychrophilic, mesophilic, and moderately thermophilic species (Vishnivetskaya et al., 2009). E. profundum was also a frequent isolate. It is described as a halotolerant and moderately thermophilic bacterium, and it has been isolated from hydrothermal vents in the Pacific Ocean at depths of about 2,600 m (Crapart et al., 2007). Aeromonas hydrophila is a bacterium that has not been associated with high temperatures (Janda & Abbott, 2010). However, some bacterial strains that are closely related to Aeromonas salmonicida (Huang et al., 2011) and A. sober have been obtained from hot springs in Tibet (Yim, Hongmei, Aitchison, & Pointing, 2006).

The region of Araró is close to the geothermal zone of Los Azufres, which comprises several hot springs, fumaroles, and boiling mud pools, and was explored in the 1980s for its geothermal potential (Birkle & Merkle, 2000). Recently, the microbial diversity in microbial mats and mud pools from Los Azufres were analysed by T-RFLP and 16S rRNA gene library analyses, and the presence of a few genera, such as Rhodobacter, Acidithiobacillus, Thiomonas, Desulfurella, and Thermodesulfobium, was reported. The authors were also able to isolate 2 sulphate and sulphur reducers related to Thermodesulfobium and Desulfurella (Brito et al., 2014). Our results are not comparable to those found by Brito and colleagues, since the thermal systems, project goals, and methodologies to assess the bacterial diversity were very different. Tina and Bonita hot springs exhibit clear water emissions with well-formed, colourful microbial mats, while Brito and colleagues mainly analysed microbial mats from mud pools. This difference supports a previous suggestion that the Araró region represents an independent thermal system from Los Azufres, despite their close proximity (Viggiano-Guerra & Gutiérrez-Negrín, 2005). However, the microbial diversity from the 2 thermal systems contains strains with potential biotechnological applications.

The Araró hot springs are extreme thermophilic environments with elevated concentrations of salts and As. This is in agreement with diversity indexes that indicate low bacterial diversity. In addition, no significant changes in the microbial communities were detected over the 4 samplings. Our results suggest that the dominant species of Firmicutes inhabit and remain part of microbial mats in these springs. The Sørensen analysis also shows that Tina and Bonita hot springs share 64% of their bacterial species. However, similarity was variable, with some seasons showing similarities below 50%, suggesting that that these springs are independent from each other. However, a deeper analysis by PhyloChip or 16S rDNA gene pyrosequencing could reveal a wide panorama of non-culturable microbial communities in both hot springs.

No significant correlation was found between temperature and bacterial diversity in Tina spring. However, for Bonita, our results suggest a significant correlation with this parameter. This is probably due to the stability of the bacterial community in Bonita spring throughout the year, with microbial mats that were maintained at about 1 cm thickness. It is also a closed system, in which the water emission is very low and water remains stagnant, with no entry or exit of water streams except for rainfall. Microbial communities may be affected by light and changes in temperature across seasons ranging from 45 °C to 55 °C and an environment that changes from a mesophilic to a thermophilic one. In the case of Tina, a thermophilic environment is maintained. The influence of temperature on the diversity of microbial communities has been widely reported for other hot springs (Ferris and Ward, 1997, Mackenzie et al., 2013, Purcell et al., 2007, Ward et al., 1998, Yim et al., 2006).

A significant correlation was also found between pH, Mg, and arsenic concentrations and bacterial community composition for Bonita, but not for Tina spring. In contrast, salt concentrations, electrical conductivity, and biological oxygen demand were correlated with bacterial community composition in Tina spring. Some hot springs, including some located in China and Chile (Hou et al., 2013, Mackenzie et al., 2013), have considerable salt quantities. Sulphates, in particular, have been shown to affect archaeal and bacterial communities along with elevated temperatures, so it is suggested that, together, salt concentrations and temperature regulate prokaryotic diversity in thermophilic environments (Purcell et al., 2007).

Previous reports on the water quality of thermal recreational springs in Araró suggest high concentrations of As, with values ranging from 0.01 mg/L to 6.26 mg/L, which exceeded the World Health Organization (WHO) and Mexican regulations for drinking water use and suggested a potential health risk (Vázquez-Vázquez, Cortés-Martínez, & Alfaro-Cuevas, 2015). Preliminary results in our lab show that most of the Bacillus strains isolated from Tina and Bonita springs contain putative arsenic resistance (ars) genes, which allow the bacteria to survive in elevated As concentrations. Several thermophilic strains of Bacillus isolated from Araró hot springs are being evaluated for bioremediation of metal pollutants.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)