1. INTRODUCTION

In situ recycling of pavements using cement is a well-tested technique nowadays. The first trials of this method in other countries, including the USA and France, took place in the 1950s. Since 1985, the technique has been gaining importance and has been considerably improved (Jasienski, 2002).

Since the mid-1950s, soil improvement and stabilization have played an increasingly important role in the construction of German roads. This applies to all road categories, from extremely busy motorways to farm tracks with very little traffic. The construction methods have been frequently modified and their fields of application continually broadened (Neussner, 2001).

As improvements have been made to application technologies and construction machinery, both in situ and in-plant mixing methods have been extended to all layers of the pavement structure (Neussner, 2001).

In Southern Africa, cement stabilization of the base and subbase layers has been used extensively both for new construction and in the rehabilitation and upgrading of existing pavements. More than 80% of all rural pavements in this region use a chemical stabilization product in at least one pavement layer. The typical Southern African pavement design consists of a crushed stone or cement base and cement-stabilized subbase with natural gravel in selected layers. A thin asphalt surface, usually 40 mm thick, or alternatively a double or single bituminous seal, depending on the design traffic, then forms the surface layer (Calitz & van Wijk, 2001).

Semi-rigid pavement (or semi-flexible in some countries), originally termed Resin Modified Pavement, was developed in France in the early 1960s as a cost-effective alternative to Portland Cement Concrete Pavement (Gawedzinki, 2008). The semi-rigid pavement is a composite pavement material consisting of a porous asphalt concrete (PAC) with air voids accounting for 25-30% (by volume of Marshall mix design), which is filled or flooded with a specially formulated high-performance polymer-modified cement mortar grouting material. As a result of this design, the semi-rigid pavement system combines the characteristics of PAC and Portland cement concrete (PCC) pavement. Since the 1990s, semi-rigid pavement has become popular throughout Europe, the USA, Africa, and Asia for both new construction and the maintenance of civil infrastructures such as roads, airfields, sea ports, industrial heavy loading yards, and so on (Dong et al. 2011).

Semi-flexible pavement is generally described as an open-graded asphalt concrete mix filled with Portland cement grout. It is a composite pavement surface that uses a unique combination of asphalt concrete and Portland cement concrete materials in the same layer (Hao et al. 2003).

In our case, semi-rigid pavement is described as a densely graded asphalt concrete mix comprising a crushed stone base layer stabilized with Portland cement to form a rigid layer.

Semi-rigid pavement has a higher composite modulus of elasticity than a flexible pavement and behaves similarly to a rigid structure in terms of how traffic loads are distributed over the subgrade (TXDOT, 2016)

The renovated road section runs from km 217+500 to km 252+000 of the Acatzingo-Mendoza highway on carriageway “A”.

1.1. GENERAL SITE DATA

The design specifications for the rehabilitated pavement structure were taken to be an Average Daily Traffic of 5,836 vehicles per day in the design lane, comprising 7% buses, 15% trucks, and 26% semi-trailers.

The road section is located in a region with mountainous topography, mean annual precipitation of 2,000 mm, and temperatures ranging between 5 and 20 °C over the course of the year.

1.2. IN SITU STABILIZATION BY RECYCLING USING PORTLAND CEMENT

Preliminary studies must be carried out rigorously. This is an essential condition for the success of recycling, and involves determining the mechanical characteristics of the material to be recycled:

The original road surface is destroyed by means of a traditional milling machine.

Motor graders are used to spread and level the new material in accordance with the project design.

Once the new material has been spread and leveled, the road recycler begins to recycle the pavement in situ to a depth defined in the project specifications. The machine cuts and pulverizes the pavement material, mixing it with the new material to form a rigid layer with the cement slurry. The cement slurry is mixed in by the machine’s mixer, avoiding sedimentation issues. The quantity of Portland cement is precisely metered at all times. The stabilized layer is then immediately compacted using a sheepsfoot compactor.

Following compaction by sheep foot compactor, with the surface properly prepared, the layer is finally compacted using a smooth vibratory roller. The percentage compaction of the base treatment cement was 100% according to Mexican standards.

Once compaction is complete, pre-cracking is performed on the stabilized layer, in accordance with design specifications. Joints are then sealed using an elastomeric sealant and finally a prime coat is applied to avoid seepage.

An asphalt layer is laid over the surface.

In this project, we use the Wirtgen W2500 SS cold recycling machine. The compressive strength of the stabilized base was 120 kg/cm2 at 14 days.

1.3. LIFE CYCLE COST ANALYSIS.

Life cycle cost analysis (LCCA) is an economic process used to compare competing design alternatives. It considers all of the significant costs and benefits, expressed in dollar equivalents, over the lifetime of each alternative. It is important to understand that LCCA is an economic tool that determines which alternate represents the best value and not an engineering tool to determine how long an alternative will last or how well it will perform.

For the rehabilitation of the section of pavement studied, two pavement proposals were put forward. The first was to recover the existing pavement and form an asphalt-stabilized base, while the second was to form a stabilized base using Portland cement. To determine which pavement to use in this project, an LCCA was performed, taking into account the initial costs (construction cost), maintenance costs, and salvage value of each alternative. Operational costs were not taken into account as it was judged that both proposals would perform similarly.

For the purposes of the analysis, a central bank rate of 12% was assumed, as this is the rate set by the Mexican Treasury. The results are presented below in US dollars.

According to Table 1, rehabilitation of the pavement with Portland cement was the more economical option in terms of both construction and maintenance of the pavement.

Table 1 Comparison between pavement with asphalt-stabilized base and pavement with cement-stabilized (US dollars)

| Pavement with asphalt stabilized base |

Pavement with cement - stabilized |

Difference (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construction cost | 749,333 | 621,979 | 17.0 % |

| Maintenance cost | 332,513 | 254,395 | 23.5 % |

| Total cost | 1,081,846 | 846,374 | 19.0 % |

| Salvage cost | 25,011 | 20,760 | 17.0 % |

| Final cost | 1,056,835.1 | 855,613.6 | 19.0 % |

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. GRAIN SIZE ANALYSIS OF PAVEMENTS (GRADING CURVES)

A textural analysis of the soil is performed by dividing the soil into individual primary particles, followed by fractionation and quantification of each particle size interval by sieving. This testing method provides a quantitative assessment of the distribution of particle sizes in soils. The distribution of particle sizes may be determined using the No. 4 (4.75 mm), No. 40 (425 μm), or No. 200 (75 μm) sieve instead of the No. 10. The entire test was performed in accordance with ASTM 422-63 (ASTM, 2007) using a dry process.

2.2. VERIFICATION OF BASE DESIGN STRENGTH

Core extraction is performed using a wet coring machine with a diamond core barrel. Special care is taken when handling samples to avoid contamination as per the ASTM C42 standard (ASTM, 2013). The core samples must have a minimum diameter of 0.1 to 0.15 m, depending on the size of the aggregate, and are drilled to different depths.

This method consists of applying a compressive axial load to molded cylinders or cores at a rate that is within a prescribed range until failure occurs. The compressive strength of the specimen is calculated by dividing the maximum load attained during the test by the cross-sectional area of the specimen. The compressive strength was tested at a specified age of 14 days.

2.3. HEAVY WEIGHT DEFLECTOMETER (HWD) TESTS ON PAVEMENTS

Measurements were made on the Acatzingo highway using an HWD capable of determining the uniformity of the test pavement structures and taking measurements of pavement response as traffic testing proceeded. Both 18- and 12-inch diameter segmented plates were used. The load pulse width was varied from 20 to 60 msec. The standard configuration (for routine tests) for the Federal Aviation Administration HWD was established with the following parameters: a segmented 12-inch loading plate, a pulse width of 27-30 msec, and four drop heights consisting of a 36-kip “seating drop” followed by impact loads of 12, 24, and 36 kips. The first 36-kip drop “seats” the pavement by settling out residual permanent deformations within the pavement structure and is not used in the analysis. The peak loads and deflections were recorded for all four drops along with air and pavement surface temperatures. The seismometers were placed at 12-inch intervals to record the response data.

HWD tests were conducted in December 2013. Pavement surface deflections were measured at an approximate load level of 50 kN. The test locations were set at intervals of 200 m along the slow lane (longitudinally, in the Acatzingo-Mendoza direction).

3. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

To determine the characteristics of the resulting cement-stabilized base following rehabilitation, the results of 79 quality control tests conducted during the work were analyzed. During all tests, the type of hydraulic cement used was gray ordinary Portland cement, which has better performance during concrete curing (less time). These tests consisted of grain size analyses (reclaimed plus new material) and unconfined compressive strength tests at 14 days. The dosage of the mixture was between 180.6 and 201.6 kg of Portland cement according to the sand and gravel found on the field during recovery of the pavement.

3.1 GRAIN SIZE ANALYSIS.

The unbroken lines in Figure 1 show grading curves for the 79 samples of material analyzed. The dashed lines show the boundaries delimiting the area in which the grading distribution of material should lie for base materials used in highway construction according to Mexican standards. The central and lower dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits that apply to material used for high-specification roads.

We observe that the samples are not homogeneous, given the differences in the size and number of particles that they comprise. Additionally, we observe that many of the grading curves lie outside the quality range (marked by a double arrow) stipulated in the Mexican standard.

Figure 2 shows that only 49% of samples contain amounts of gravel compliant with the ASTM D422 standard (more than 50% of particles measuring more than 4.75 mm).

Figure 3 shows that beyond km 232+800, almost all samples of material contain more than 50% gravel (size greater than 4.75 mm).

Looking at Figure 3, we observe that the percentage of gravel contained in the samples of material obtained between km 217+500 and km 220+500 and between km 223+000 and km 239+000 ranges between 35 and 68%, with means of 47.2 and 48.9% respectively. Conversely, in sections km 220+500 to km 223+000 and km 239+000 to km 252+0000, the gravel content comply with the ASTM D422 standard, having mean values of 52.1 and 57.6%.

Figure 4 shows that of the 79 samples obtained for quality control purposes, 70% comply with the specifications set out in the Mexican standard N.CMT.4.02.002; that is, they contain less than 5% fine material (particles smaller than 0.075 mm), with 29% of samples containing between 5 and 10% fine material and only the remaining 1% having a fine content above 10%.

Figure 5 shows that in the section of road between km 217+500 and km 223+000, the fine particle content lies between 1 and 5%, with a mean of 3.2%, while in the section between km 223+000 and km 252+000, as above the percentage of fine particle content lies between 1 and 11%, with a mean of 5.2%.

Figure 6 is a plot of the coefficients of uniformity over the section of road studied. We observe that all samples of material have a coefficient of uniformity (Cu) greater than 10. A coefficient of uniformity greater than 10 indicates that the sample of stone material is made up of particles of diverse sizes.

In Figure 7, coefficients of curvature are plotted for the 79 samples analyzed. We observe that 80% of data points have a coefficient of curvature of less than 1, with 16% being between 1 and 3 and 3% being greater than 3. When a grading curve has a coefficient of curvature between 1 and 3, this means that the material in question contains particles of all sizes.

3.2 UNCONFINED COMPRESSIVE STRENGTH

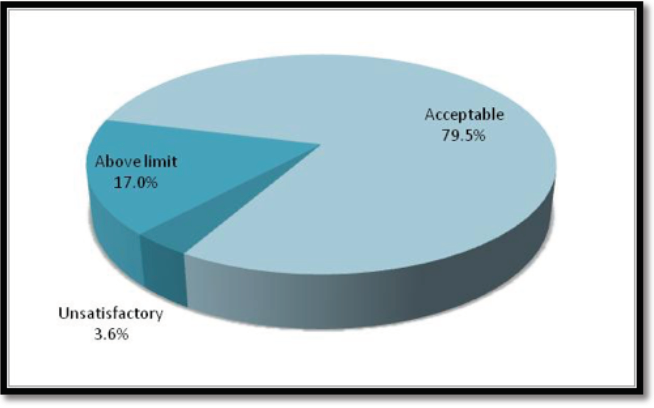

Figure 8 shows that 96.4% of cores whose unconfined compressive strength was measured after 14 days comply with the minimum acceptable resistance of 114 kg/cm2 (120 kg/cm2 -5%) stipulated in the project design specifications.

Figure 9 shows the percentage of measurements exhibiting high resistance. It should be noted that the design specifications do not stipulate an upper resistance limit for the stabilized base, but for the purposes of the present analysis, we consider it useful to observe the results when such a limit is set. The limit was set at 175 kg/cm2, which is equal to the mean resistance plus one standard deviation. It can be seen that 17.0% of cores sampled exceed the set limit.

Figure 9: Unconfined compressive strength: percentage of samples that are unsatisfactory, acceptable, or above the limit

By plotting the resistance of the sample cores, we observe in Figure 10 that the greatest variation in resistance of the cement-stabilized base occurs in the section between km 223+500 and km 235+000:

From km 217+500 to km 220+500, resistance values are up to 230 kg/cm2, 92% above the design resistance.

From km 220+500 to km 223+000, resistance values are up to 165 kg/cm2, 38% above the design resistance.

From km 223+000 to km 239+000, resistance values are up to 245 kg/cm2, 104% above the design resistance.

From km 239+000 to km 252+000, resistance values are up to 193 kg/cm2, 60% above the design resistance.

The cement content by weight according to the mix design was 11 to 13%.

3.3 DEFLECTION VALUES

Figure 11 shows a comparison between the measured deflection before and after completion of the rehabilitation work. The red line shows deflection prior to rehabilitation, with values ranging between 109 and 2091 µm and an arithmetic mean of 607 µm; the blue line shows deflection after completion of the rehabilitation work, exhibiting values between 74 and 197 µm and a mean of 113 µm, thus representing an improvement in the quality of the structure.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Stabilization via in situ recycling with cement is an excellent recycling technique. It improves existing material without producing waste and limits the transportation of new products. This technique has a promising future.

A cement-stabilized base was successfully produced and was found to contain a homogeneous mixture of stone materials and cement, forming a layer with a uniform appearance in both transverse and longitudinal directions. In 96.4% of cores, a design resistance of 120 kg/cm2 was achieved, allowing for a -5% tolerance and hence a minimum permitted resistance defined as 114 kg/cm2.

The results of resistance testing on the cores exhibit a wide range of values, more than 100% above the design resistance in some cases. No upper limit on resistance was specified in the current project, but we conclude that there is a need to set a maximum resistance for future projects.

From our analysis of the grading curves, we found that material samples are not homogeneous, exhibiting large differences in the size and number of particles, with many of the curves lying outside the quality range indicated in the N.CMT.4.02.002 standard; many of the samples comprise different particle sizes (Cu > 10) with only a few exhibiting a uniform range of sizes (1 < Cu < 3).

Given the heterogeneous nature of the materials used for construction of the cement-stabilized base (reclaimed material plus new material), the amount of cement required to achieve the design resistance was determined for the most critical case and this measure was then applied uniformly over the entire construction process, resulting in the variation in resistance that we observe over the concrete-stabilized base.

In future projects, the proposed frequency of probing will be increased to more accurately determine locations where there is significant variation in the quality of materials to be recycled and therefore to acquire the necessary information to optimize the mix designs.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)