Highlights:

Agricultural and grassland areas dominate the landscape in the wind farm area.

Wind infrastructure covers less than 1 % of the area studied.

Preserved fragments of Tamaulipan thornscrub (TT) account for 20.63 %.

Fabaceae, Poaceae and Cactaceae families had greater presence in TT fragments.

Vegetation fragment configuration favors the creation of biological corridors.

Introduction

Wind power industry development in Mexico has grown significantly in the last decade (Azamar Alonso & García Beltrán, 2021). The states with the highest production include Tamaulipas with 1 177.5 MW installed (Robles, 2017). This area is predominantly home to the Tamaulipas Thornscrub (TT), characterized by its ability to adapt to extreme climate conditions and soil nutrient fixation (Foroughbakhch et al., 2011; González-Rodríguez et al., 2016).

TT's surface area has decreased since the 1980s, mainly due to the extensive practice of livestock and agriculture (Turner & Díaz-Bautista, 2009). Just in the period from 1993 to 2002, 953,000 ha of scrubland were lost due to land use change, being the second most affected ecosystem in Mexico after rainforests (Patiño-Flores et al., 2021).

The distance between wind turbines in wind farms must be at least 5 % of their diameter (Ramírez et al., 2016), so that the wind turbines together form a large area. A common practice to reduce the impact is to install these farms in areas that already have some type of use, usually agricultural (Ecological Society of America [ESA], 2019). However, land use change due to the establishment of wind infrastructure, access roads and operational area can cause additional fragmentation to the ecosystem (Hernández-Pérez et al., 2022). This results in a new spatial configuration that is reflected in the quantity, distance, richness and shape of fragments (also referred to as patches) that make up the land uses (Rodríguez-Echeverry & Leiton, 2021). These changes can be evaluated using landscape analysis methods, such as the classification of satellite images and the calculation of landscape metrics (Altamirano et al., 2012). Satellite images are processed by means of geographic information systems, where information about vegetation cover is obtained by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index or NDVI (Olivares & López-Beltrán, 2019). Meanwhile, landscape metrics allow obtaining information about the spatial relationships between the fragments that make up the landscape mosaic (Mateucci & Silva, 2005).

Increased fragmentation in vegetation areas reduces the habitat available for the development of species, even more when crops, roads, human settlements or induced vegetation predominate (Reyes et al., 2022). The remaining vegetation cover is a determining factor in the degree of affectation that a wind system has on fauna (Bolívar-Cimé et al., 2016). Therefore, in addition to knowing the composition and configuration of the landscape, it is important to evaluate the plant community distributed in a fragmented system, especially to document changes in the plant structure by identifying species sensitive to these changes.

The objectives of this research were a) to characterize and describe the degree of fragmentation in a wind farm with agricultural activities and, b) to recognize its structure and diversity in the fragments with vegetation use of TT. It is expected that the elements studied will serve as indicators for future studies focused on the creation of biological corridors within productive systems.

Materials and Methods

Study area

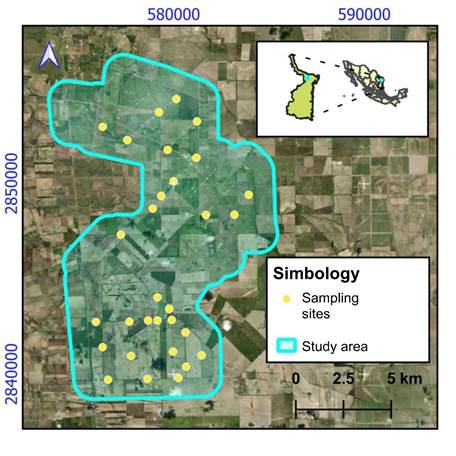

The study area covers an area of 14 031.98 ha in a wind production zone in the municipality of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico. There are 103 generators in the area with a production capacity of 321 MW.

Currently, land tenure is diversified into three private productive activities: wind energy generation, agriculture and livestock (grassland); however, there are still areas conserved with TT vegetation, where livestock has no access. The climate is classified as BS1 (h’) hx’ (García, 2004) which corresponds to a warm semi-dry climate with average annual precipitation ranging between 500 and 700 mm and average annual temperature of 22 °C. The soil types are Castañozem, Vertisol and Xerosol, according to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI, 2017).

Landscape analysis

Land use was determined using QGIS Desktop (2022) version 3.26.3. The procedure proposed by Sader and Winne (1992), which uses the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), was used to visualize vegetation cover dynamics. NDVI enhances the greenness associated with vegetation by quantifying near red and infrared bands. This process allows the reduction of data volume, but keeps a semi-continuous variable correlated with vegetation biomass and green leaf area index. The Sentinel-2B satellite image dated January 6, 2022 was used for this study. Subsequently, NDVI was generated and geometric and atmospheric corrections were applied. The first, by georeferencing to the Coordinate Reference System WGS84 UTM zone 14 N and the second by using the Semi Automatic Classification Plugin. A supervised classification of the RGB-NDVI image (Red-Green-Blue band correction image) was performed for the identification of land uses. Data was corroborated by field visits, including visual inspections of plot contents in contrast with the software results (Vega-Vela et al., 2017). Also, a direct on-screen digitization was made of the roads and wind turbine areas that make up the wind farms. The product was a map in vector format, in which the area (ha) of each land use was estimated. Based on this information, landscape metrics were calculated to quantify the spatial relationships between land uses. All fragments were grouped according to use category, an alphanumeric identification was assigned to each one and the information was rasterized to be entered into the FRAGSTATS version 4.2 program (McGarigal & Marks, 1995). Wind turbine land use was not included in this analysis as it was not detected in the rasterization process, due to its small percentage of surface area. One metric was calculated at the fragment level (Euclidean distance to nearest neighbor ENN_MN) and four at the class level (number of fragments NP, average fragment area AREA_MN, shape index SHAPE_MN and fractal dimension index FRAC_MN).

Vegetation analysis

In November 2021, the plant community in the elements identified as vegetation fragments of TT was analyzed. We established 30 sampling sites (Figure 1) divided into two strata (Mata-Balderas et al., 2020). The high stratum included shrub and tree vegetation with heights ≥2 m in rectangular plots of 75.0 m2. The low stratum included herbaceous vegetation ranging from 0.30 to 1.99 m in height, within a 1 m2. Species were identified using taxonomic keys and flora catalogs of the area (Correll & Johnston, 1970; Molina-Guerra et al., 2019). Tree measurement variables of total height (h), crown diameter in north-south and east-west directions, and diameter at breast height (D1.30) in woody species were measured, only basal diameter (D0.10) was measured in low species (Alanís et al., 2020).

Figure 1 Vegetation sampling sites in fragments of Tamaulipan Thornscrub in a wind farm area in the municipality of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico. Source: Esri Map Services (2017).

Data analysis

Abundance, cover and frequency were the floristic composition parameters determined. These were used in their relative form to determine the weighted value known as the Importance Value Index (IVI) (Magurran, 2004; Mueller-Dombois & Ellenberg, 1974). Vegetation alpha diversity was estimated using Shannon-Wiener's diversity index (H’), Margalef's richness index (D mg ) and Simpson's index (D). The first describes how diverse a specific habitat can be, taking into account the number of species present and their number of individuals. The second evaluates the biodiversity of a community, according to the numerical distribution of individuals of the species found. The last refers to dominance, considering whether a community is determined by species with a high abundance value (Cadena-Zamudio et al., 2022; Magurran, 2004; Manzanilla et al., 2020). Beta diversity was evaluated by means of a similarity dendrogram based on species abundance, using the Bray-Curtis ordination model (Whittaker, 1960), generated in the PAST version 4.13 statistical program (Hammer et al., 2001).

Results

Landscape analysis

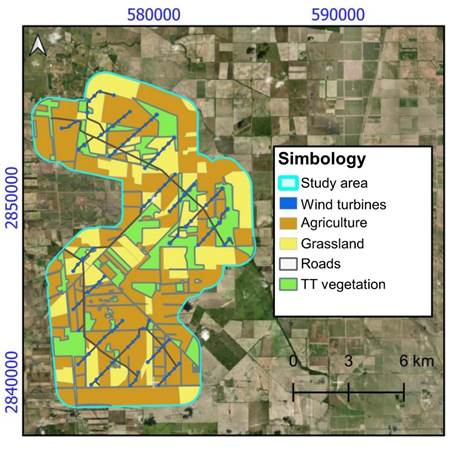

The multipurpose productive system comprising the study area has five land uses (Figure 2). Agriculture and grassland activities (for livestock) cover the largest area with 53.53 % and 25.31 %, respectively, followed by TT vegetation areas (20.63 %), roads (0.51 %) and wind turbines (0.01 %).

Figure 2 Land uses in a wind farm area in the municipality of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico. TT: Tamaulipan Thornscrub.

Regarding landscape metrics calculation, agricultural use had the largest area fragments (3 720.49 ha), followed by grasslands (582.22 ha), TT vegetation areas (429.92 ha) and finally roads (5.06 ha). According to Table 1, for ENN_MN, vegetation fragments had the highest aggregation because they yielded the lowest value (173 m), followed by agriculture fragments (180 m), roads (250 m) and grasslands (462 m). Grasslands similarly had the highest spatial complexity by presenting the value furthest from '1' in the SHAPE_MN metric, contrary to roads which had the closest value. FRAC_MN values vary from 1.04 to 1.08, so, based on their area and perimeter, there is no considerable variation in the degree of complexity between classes. Regarding NP, roads (146) and vegetation fragments (100) showed the highest values, contrary to agricultural (42) and grassland (25)

Table 1 Land use and landscape metrics at class level in a wind farm area in the municipality of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico.

| Land use | Area (ha) | Number of fragments | AREA_MN (ha) | ENN_MN (m) | SHAPE_MN | FRAC_MN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT vegetation | 2 894.25 | 100 | 1.66 | 173 | 1.66 | 1.08 |

| Grassland | 3 552.13 | 25 | 141.89 | 462 | 1.70 | 1.07 |

| Agriculture | 7 513.17 | 42 | 179.41 | 180 | 1.55 | 1.04 |

| Roads | 71.42 | 146 | 1.25 | 250 | 1.25 | 1.04 |

AREA_MN: average fragment area; ENN_MN: Euclidean distance to nearest neighbor; SHAPE_MN: shape index; FRAC_MN: fractal dimension index. TT: Tamaulipan Thornscrub.

Vegetation analysis

Table 2 shows the 47 species recorded, corresponding to 23 families, regarding the composition of the TT vegetation cover. Fabaceae, Poaceae and Cactaceae showed the highest presence, with eight, six and five species, respectively. In the upper stratum, Celtis pallida Torr. (granjeno), Neltuma glandulosa Torr. (mezquite dulce), Forestieria angustifolia Torr. (panalero) and Ebenopsis ebano (Berland.) Barneby & J. W. Grimes (ebano) had higher abundance, cover and average height. Together, these provided 97.86 % of the 300 % of importance. In the lower stratum, the species of greatest importance were Cenchrus ciliaris L. (zacate buffel; 114.77 %) and Sorghum halepense (L.) Pers. (African canary grass; 76.04 %). Absolute abundance for the high stratum is 6 824 individuals∙ha-1 with a total canopy cover of 224.19 m2∙ha-1 and average height of 1.64 m. In the low stratum, the values of these parameters are at 87 000 individuals∙ha-1, 606 m2∙ha-1 and 0.31 m, respectively.

Table 2 Values of absolute abundance, canopy cover, average height and importance value index (IVI) of the Tamaulipan Thornscrub vegetation cover in a wind farm area in the municipality of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico.

| Family | Scientific name | Abundance (individuals∙ha-1) | Cover (m2∙ha-1) | Average height (m) | IVI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ulmaceae | Celtis pallida Torr. | 1 351 | 7.95 | 2.61 | 33.04 |

| Fabaceae | Neltuma glandulosa (Torr.) Britton & Rose | 613 | 18.29 | 4.31 | 27.21 |

| Oleaceae | Forestiera angustifolia Torr. | 613 | 7.25 | 1.98 | 19.68 |

| Fabaceae | Ebenopsis ebano (Berland.) Barneby & J. W. Grimes | 324 | 16.17 | 4.43 | 17.93 |

| Rhamnaceae | Karwinskia humboldtiana (Willd. ex Schult.) Zucc. | 387 | 4.16 | 1.23 | 14.24 |

| Zygophyllaceae | Guaiacum angustifolium (Engelm.) A. Gray | 364 | 3.59 | 0.95 | 11.79 |

| Boraginaceae | Cordia boissieri A. DC. | 178 | 9.06 | 2.53 | 10.75 |

| Fabaceae | Coursetia axillaris J. M. Coult. & Rose | 378 | 4.65 | 1.93 | 9.85 |

| Fabaceae | Havardia pallens (Benth.) Britton & Rose | 191 | 8.23 | 2.51 | 9.83 |

| Cactaceae | Opuntia engelmannii Salm-Dyck ex Engelm. | 93 | 10.59 | 1.27 | 9.45 |

| Fabaceae | Senegalia greggii (A. Gray) Britton & Rose | 18 | 16.44 | 3.80 | 8.34 |

| Cactaceae | Leptocereus quadricostatus (Bello) Britton & Rose | 89 | 11.78 | 2.17 | 8.05 |

| Fabaceae | Vachellia farnesiana (L.) Wight & Arn. | 67 | 8.33 | 2.10 | 8.05 |

| Rutaceae | Zanthoxylum fagara (L.) Sarg. | 160 | 5.49 | 1.57 | 7.78 |

| Fabaceae | Senegalia berlandieri (Benth.) Britton & Rose | 191 | 6.87 | 2.41 | 7.73 |

| Fabaceae | Vachellia rigidula (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger | 156 | 4.60 | 1.62 | 7.31 |

| Rubiaceae | Randia aculeata L. | 129 | 3.46 | 0.99 | 7.16 |

| Rosaceae | Prunus serotina Ehrh. | 320 | 3.44 | 0.75 | 6.97 |

| Fabaceae | Cercidium macrum I. M. Johnst. | 13 | 13.33 | 2.73 | 6.89 |

| Ebenaceae | Diospyros texana Scheelee | 98 | 6.61 | 1.78 | 6.62 |

| Asparagaceae | Yucca treculeana Carriére. | 71 | 4.61 | 1.28 | 6.08 |

| Sapotaceae | Sideroxylon celastrinum (Kunth) T. D. Penn | 138 | 4.87 | 1.77 | 6.06 |

| Verbenaceae | Lantana camara L. | 151 | 3.03 | 1.00 | 5.43 |

| Solanaceae | Lycium berlandieri Dunal. | 89 | 4.24 | 1.28 | 5.43 |

| Rhamnaceae | Condalia hookeri M. C. Johnst. | 36 | 7.78 | 2.25 | 4.74 |

| Solanaceae | Capsicum annuum L. | 76 | 3.66 | 1.17 | 4.60 |

| Cactaceae | Cylindropuntia leptocaulis (DC.) F. M. Knuth | 58 | 4.27 | 1.23 | 4.24 |

| Malvaceae | Abutilon fruticosum Guill. & Perr. | 151 | 2.78 | 0.73 | 4.20 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton cortesianus Kunth. | 58 | 3.62 | 0.93 | 3.96 |

| Simaroubaceae | Castela texana (Torr. & A. Gray) Rose | 40 | 4.20 | 1.42 | 3.58 |

| Fabaceae | Erythrostemon mexicanus (A. Gray.) Gagnon & G. P. Lewis | 31 | 3.62 | 1.54 | 3.19 |

| Scrophulariaceae | Leucophyllum frutescens (Berland.) I. M. Johnst. | 27 | 3.78 | 0.95 | 2.82 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Jatropha dioica Sessé | 93 | 0.56 | 0.74 | 1.99 |

| Asteraceae | Gymnosperma glutinosum (Spreng.) Less. | 31 | 0.89 | 0.29 | 1.97 |

| Cactaceae | Thelocactus setispinus (Engelm.) E. F. Anderson | 9 | 0.44 | 0.15 | 1.07 |

| Verbenaceae | Aloysia macrostachya (Torr.) Moldenke | 9 | 1.11 | 0.30 | 1.00 |

| Cactaceae | Echinocereus enneacanthus Engelm. | 27 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.96 |

| Poaceae | Cenchrus ciliaris L. | 47 000 | 109.93 | 0.40 | 114.77 |

| Poaceae | Sorghum halepense (L.) Pers. | 26 667 | 95.42 | 0.45 | 76.04 |

| Asteraceae | Parthenium hysterophorus L. | 3 667 | 85.76 | 0.28 | 27.64 |

| Asteraceae | Helianthus annuus L. | 1 667 | 90.00 | 0.90 | 20.48 |

| Petiveriaceae | Rivina humilis L. | 1 667 | 66.67 | 0.25 | 14.78 |

| Boraginaceae | Heliotropium angiospermum Murray | 2 000 | 34.44 | 0.15 | 13.54 |

| Poaceae | Chloris virgata P. Durand | 333 | 40.00 | 0.20 | 8.84 |

| Poaceae | Bouteloua trífida Thurb. ex S. Watson | 2 333 | 23.33 | 0.05 | 8.39 |

| Poaceae | Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | 667 | 33.33 | 0.20 | 8.12 |

| Poaceae | Melinis repens (Willd.) | 1 000 | 26.67 | 0.25 | 7.41 |

Alpha diversity yielded a value of 3.18 for Shannon's index, 0.93 for Simpson's index and 6.13 for Margalef's index. Figure 3 shows the dendrogram derived from the beta diversity analysis, which indicates that the sampling sites show average similarity based on plant species abundance. Of the 30 sites evaluated, 15 are grouped above 50 %, but only two are grouped in the highest percentage of similarity with 62 %.

Discussion

According to the land use classification, the system in the study area can be classified as agroforestry, particularly as agropastoral, since it combines the presence of woody species with agricultural and livestock practices (Cabrera et al., 2011); however, by including wind farm activities, it has been called a multipurpose system. In this system, the native vegetation of TT is composed of a greater number of smaller, complex and poorly segregated fragments, in contrast to the agricultural and grassland uses that have a less number of fragments but are larger in size. Mateucci and Silva (2005) affirm that less anthropic territories present more complex forms and vice versa. In the present study, agricultural and grassland uses dominate the landscape due to their larger surface area. However, the proximity between vegetation fragments could facilitate the creation of biological corridors with focal species within the ecosystem (Alonso-F et al., 2017), which would require studies to establish.

Regarding the floristic evaluation of the vegetation fragments, the families with the highest number of species were Fabaceae, Poaceae and Cactaceae. Several studies in the region have reported the Fabaceae family as the most representative in several land uses (Alanís-Rodríguez et al., 2021; Jiménez Pérez et al., 2013; Pequeño Ledezma et al., 2021). This is due to its ability to fix nitrogen and withstand the conditions typical of arid zones (Reyna-González et al., 2021). On the other hand, the Poaceae family groups fast-growing non-native species, used for agropastoral activities in the surroundings of the conserved areas (Jiménez Pérez et al., 2013). Meanwhile, the high presence of the Cactaceae family confirms its affinity for arid areas (Mata Balderas et al., 2015). These results coincide with those found by Vargas-Vázquez et al. (2022) in the municipality of Reynosa and with Foroughbakhch et al. (2013) in areas of Tamaulipas, which show a good conservation of these families in the region.

Of the Fabaceae family, N. glandulosa had the highest mean cover and height values and the second place in abundance. Similarly, the cover of N. glandulosa (17.88 m2∙ha-1) was higher compared to that of E. ebano (4.79 m2∙ha-1) in a plantation in the municipality of Rio Bravo (Garcia-Mosqueda et al., 2014) contiguous to that of the present project. In the study by Foroughbakhch et al. (2013), N. glandulosa was the most important in recovery sites in Tamaulipas. This confirms that the conditions recorded in and around the study area are suitable for the establishment of this species.

The four species with the highest IVI (C. pallida, N. glandulosa, F. angustifolia and E. ebano) have been reported in diverse land uses, both in disturbed areas that are in the process of regeneration (Alanís-Rodríguez et al., 2021) and in areas with deep soils, rich in nutrients and moisture (Pequeño-Ledezma et al., 2017). In the present assessment, these species account for almost a third of the total importance for the upper stratum.

Regarding the absolute abundance for all vegetation (6 828 individuals∙ha-1), the amount is above that reported by Mora et al. (2013b) in reference to regeneration and livestock areas. But is similar to the 6 310 ± 523 individuals∙ha-1), recorded by Jiménez Pérez et al. (2013) in a regenerated clear cutting area. The specific richness for the shrubby tree stratum (37) is higher than that reported in other TT areas of between 10 and 28 years of regeneration (Jiménez et al., 2012; Mora et al., 2013a; Reyna-González et al., 2021); however, it is lower than the 55 recorded (mostly shrubby) by Vargas-Vázquez et al. (2022). The diversity (H') and richness (Dmg) indices yield higher values than pristine TT (Valdez et al., 2018), regenerating (Patiño-Flores et al., 2022), post-fire (Graciano-Ávila et al., 2018) and agroforestry (Alanís-Rodríguez et al., 2018; Sarmiento-Muñoz et al., 2019) ecosystems. Similarly, Simpson's index supports high diversity by yielding a value close to 1 (Valdez et al., 2018).

The results of the Bray-Curtis model show the variability of species abundance in the area. The multiple groupings may be a product of taxa adapting to the characteristics of the evaluation sites (Silva-García et al., 2022). Examples of this are the genera Jatropha, Croton, Opuntia and Cylindropuntia which tend to be found mostly on slopes or steep slopes (Foroughbakhch et al., 2013; Reyna-González et al., 2021).

Conclusions

The wind farm area has a set of anthropogenic activities dominated by agriculture and livestock, which is why it has been called a multipurpose system. These activities form fragments of Tamaulipan Thornscrub vegetation that are scarcely modified based on their characteristics. The richness and diversity of this flora presents higher values compared to other ecosystems with better conservation conditions. Thus, characterizing vegetation in this system will allow us to formulate management actions to improve wildlife connectivity within the biological corridors.

texto en

texto en