Hybridization, polyploidy and apomixis are common processes in plants, which can cause enormous difficulties in delimiting one species from another and their relationships (Grusz et al. 2009). It has been estimated that 16-34 % of plant families and 6-16 % of genera have one or more hybrid reports (Rieseberg 1997). However, nearly 70 % of angiosperms have at least one polyploidization event in their history (Otto 2007, Soltis & Soltis 2009). In contrast, apomixis only occurs in 1 % of angiosperms and 75 % of apomictic taxa belong mainly to three families: Asteraceae, Poaceae and Rosaceae (Hörandl 2006). Despite the differences in the frequencies of these proccesses, apomixis is constantly associated with hybridization and polyploidy (Lovell et al. 2013).

Regarding angiosperms, attempts have been made to explain the relevance of these processes and to understand whether the occurrence of one phenomenon leads to the appearance of the other(s), and this has turned out to be a highly debated with multiple interpretations. Therefore, the main goal of this study is to investigate the relationships between these three processes and their relevance in ecological and evolutionary terms in angiosperm plant populations. First, the concepts of hybridization, polyploidy, and apomixis are defined. The results of a specialized literature search for studies to assess the three processes, are shown and the main results of the studies are described.

Hybridization. Hybridization is a process that involves the joining of genomes of two species or taxa that differ in at least one heritable character; that is, it acts in opposition to evolutionary divergence (Rieseberg 1997, Rieseberg & Willis 2007). Hybridization can take place between species with the same or different chromosome number; however, its consequences on the evolution of lineages have been widely recognized because it can increase genetic diversity, originate or transfer adaptations, reinforce or break reproductive barriers, and ultimately give rise to new species or lineages (Rieseberg 1997, Goulet et al. 2016). It is worth mentioning that the probability of allopolyploid hybrid speciation (speciation between different species) is much more common compared to homoploid hybrid speciation (speciation between species with the same chromosome number). The higher probabilities of allopolyploid hybrid speciation are because a change in the chromosome number can generate immediate isolation of hybrids from their parents (Rieseberg 1997, Gross & Rieseberg 2005, Goulet et al. 2016, Rieseberg & Willis 2007, Soltis & Soltis 2009).

Polyploidy. Polyploidy is the inheritable condition of having more than two complete sets of chromosomes (Comai 2005). The main consequence of polyploidy is the production of unreduced gametes (with the same chromosome number as somatic cells). This situation is overlooked in many individuals but can arise from the duplication of chromosomes before meiosis, the complete loss of the first or second meiotic division, defects in the cell plate formation, or the cell spindle’s orientation (Mason & Pires 2015). Polyploidy can be of the autopolyploid type, which results when an organism has more than two sets of chromosomes derived from the same individual, which generally occurs when an unreduced gamete joins a reduced one or two unreduced gametes belonging to the same species. On the contrary, allopolyploidy corresponds to organisms that contain more than two sets of non-homologous chromosomes due to hybridization between different species (Mason & Pires 2015, Otto 2007, Ramsey & Schemske 1998). Interspecific hybrids generally produce a higher frequency of unreduced gametes compared to their parents (27.5 vs. 0.6 %), probably because hybrids suffer severe meiotic irregularities that cause poor chromosome pairing and nondisjunction (Mason & Pires 2015, Ramsey & Schemske 1998). In some cases, the formation of unreduced gametes (2n) in interspecific hybrids is related to the genetic distance between the parents, i.e., the greater the genetic distance, the greater the production of unreduced gametes (Chapman & Burke 2007).

Apomixis. Sexual reproduction in angiosperms has generated a great diversity of plants; however, plants have developed asexual mechanisms to produce seeds (Lovell et al. 2013), as in apomixis or agamospermy. For this to occur, three steps are necessary: first, elusion of meiosis (apomeiosis) to produce an unreduced embryo sac; second, developing the embryo independently of fertilization (parthenogenesis); and finally, forming a functional endosperm (Aliyu et al. 2010, Bicknell & Koltunow 2004, Grimanelli et al. 2001). If the unreduced embryo sac is fertilized by a sperm cell, ploidy increases; otherwise, an embryo sac after apomeiosis without fertilization maintains its ploidy level (Hörandl 2006, Lovell et al. 2013). However, most apomictic plants are hermaphrodites and produce a functional pseudogamous endosperm; that is, they need a sperm cell (from the pollen grain) to fertilize the polar nuclei of the embryonic sac to generate a functional endosperm. It is known that some taxa of Asteraceae, among others, are capable of forming a functional endosperm in the absence of pollen (autogamous endosperm); however, they maintain the production of pollen, which can be exported to other flowers (Richards 2003, Hörandl 2006, Hörandl & Temsch 2009, Hojsgaard et al. 2014).

When the embryo develops directly from a somatic ovule cell, apomixis is called the sporophyte type, also called an adventitious embryo. In this case, the sexual reproductive route is still functional so that seeds can contain apomictic and sexual embryos. In addition, the apomictic embryo will depend entirely on the sexual endosperm because the production of seeds by sporophytic apomixis does not exclude sexual reproduction (Grimanelli et al. 2001, Tucker & Koltunow 2009). The second type of apomixis is gametophytic, which in turn is subdivided into diplosporic and aposporic apomixis. In diplosporic apomixis, the unreduced embryonic sac is formed from a mother cell of the megaspore in which meiosis was disrupted; in this case, the diplosporia replaces the process of sexual reproduction. In contrast, aposporic apomixis arises when the unreduced embryonic sac is formed from a somatic cell close to the mother cell of the megaspore that differentiates into an initial aposporic cell that will later elude meiosis and go directly to mitosis. In this case, the aposporia may allow the coexistence or degeneration of the sex cell (Carman 1997, Tucker & Koltunow 2009).

Literature search. A literature search was performed using Web of Science on August 1, 2024, using the following keyword combination: "hybrid* AND polyploidy* AND apomixis OR agamospermy".

According to the specialized literature search, 50 studies assessed hybridization, polyploidy, and apomixis in angiosperms (Table 1). Many articles were discarded because they only focused on two phenomena, mainly apomixis, and polyploidy, although in some cases, they mentioned possible past hybridizations. Table 1 only covers 9 families and 16 different genera, emphasizing Asteraceae (15) and Rosaceae (11).

Table 1 Studies about hybridization, polyploidy and apomixis in angiosperms.

| Family | Genus | Species | Main objective | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asteraceae | Hieracium | H. aurantiacum y H. pilosella | To understand the heredity patterns of apomixis in outcrossing plant species with different ploidy levels and reproductive modes. | Bicknell et al. 2000 |

| Asteraceae | Hieracium | H. pilosella, H. bauhini | To compare the capacity to generate offspring with different ploidy levels and reproductive modes between apomictic and sexual plants. | Krahulcová et al. 2009 |

| Asteraceae | Hieracium subgenus Pilosella | To build the phylogeny for the subgenus Pilosella. | Fehrer et al. 2007 | |

| Asteraceae | Taraxacum | T. scanicum | Evaluate the genotypic diversity among seven apomictic microspecies coexisting in Central Europe. | Majeský et al. 2015 |

| Asteraceae | Taraxacum | Study the inheritance of apomixis in intraspecific crosses between different ploidy levels. | Tas & Van Dijk 1999 | |

| Asteraceae | Taraxacum | T. officinale | To evaluate meiosis in sexual diploid and apomictic triploid plants to find mechanisms that explain the high levels of genetic variation. | Van Baarlen et al. 2000 |

| Asteraceae | Taraxacum | T. officinale | Describe how the apomictic development of seeds is carried out in sexual and apomictic individuals with different ploidy levels. | Van Baarlen et al. 2002 |

| Asteraceae | Taraxacum | To evaluate the inheritance of apomixis by backcrossing F1 hybrids. | Van Dijk et al. 1999 | |

| Asteraceae | Taraxacum | Describe the evolutionary patterns of the genus regarding processes such as hybridization, polyploidy and apomixis. | Kirschmer & Stepanek 1996 | |

| Asteraceae | Crepis | Crepis atribarba subsp. originalis, C. barbigera | To determine whether interspecific pollen flow from apomicts can exert reproductive interference on the sexual species in the Crepis agamic complex. | Hersh et al. 2016 |

| Asteraceae | Pilosella | Pilosella bauhini, P. hoppeana subsp. testimonialis, P. officinarum, P. onegensis, P. pavichii, P. pseudopilosella | Describe the processes that affect the population structure of the agamic complex of Pilosella in Bulgaria. | Krahulcová et al. 2018 |

| Asteraceae | Taraxacum sect. Ruderalia | Analyze the progeny of hybrids resulting from crosses between 2× and 3×. | Mártonfiová et al. 2007 | |

| Asteraceae | Pilosella | To compare male function among sexual, facultatively apomictic and seed-(semi)sterile field plants. | Rotreklová et al. 2016 | |

| Asteraceae | Erigeron | E. annus, E. strigosus | Explore the genetic basis of agamospermy in the flowering plant genus Erigeron. | Noyes et al. 2000 |

| Bachiaria | Urochloa | To characterize the nature of their genomes, the repetitive DNA and the genome composition of polyploids, including many apomictic species. | Tomaszewska et al. 2023 | |

| Brassicaceae | Boechera | To identify whether the apomictic diploids of Boechera are of hybrid origin. | Beck et al. 2012 | |

| Brassicaceae | Arabis | Arabis drummondii, A. holboellii, A. × divaricarpa | Identify the phylogeographic pattern of the Arabis holboellii complex to understand its evolution. | Dobes et al. 2004 |

| Brassicaceae | Boechera | Summarize the knowledge of the genus Boechera about apomixis, polyploidy and hybridization. | Dobes et al. 2007 | |

| Brassicaceae | Arabis | A. drummondii, A. holboellii y A. divaricarpa | Identify the inheritance of ITS regions between parental species and hybrids in Arabis complex. | Koch et al. 2003 |

| Brassicaceae | Boechera | Analyze the origin and evolution of apomixis in the genus Boechera. | Lovell et al. 2013 | |

| Brassicaceae | Boechera | Investigate phylogenetic relationships, ability to hybridize, mating system, and ploidy levels between 19 Boechera species. | Schranz et al. 2005 | |

| Brassicaceae | Boechera | B. holboellii, B. divaricarpa y B. stricta | Identify transcriptomic differences between sexual and apomictic ovules in the B. holboellii complex. | Sharbel et al. 2009 |

| Brassicaceae | Boechera | Test the potential of haploid vs. diploid pollen from apomicts to transmit apomixis factors to obligate sexual recipient lines and initiate viable apomictic progeny. | Mau et al. 2021 | |

| Lactuceae, Asteraceae | Hieracium subgen. Hieracium | For the first time, molecular markers have been used to disentangle relationships and species origins of the taxonomically highly complex Hieracium s.str. | Fehrer et al. 2009 | |

| Orchidaceae | Zygopetalum | Zygopetalum mackayi | Describe patterns of genetic diversity of pure and mixed-cytotype populations to evaluate the expected occurrence of a higher frequency of apomictic (clonal) individuals in the contact zone compared to pure cytotype populations. | Moura et al. 2020 |

| Plumbaginaceae | Limonium | L. dufourii | Evaluate the genetic contribution of each putative paternal taxon in an asexual hybrid using microsatellites (SSRs). | Palop-Esteban et al. 2007 |

| Poaceae | Paspalum | P. procurrens, P. simplex, P. usterii y P. malacophyllum | Evaluate the reproductive mode the ploidy level and perform interspecific crosses between four species of Paspalum, to determine how similar their genomes are. | Hojsgaard et al. 2008 |

| Poaceae | Paspalum | Paspalum compressifolium, P. lenticulare, P. nicorae, P. rojasii | To conduct cytogenetic analyses of inter- and intraspecific hybridizations involving a sexual, colchicine-induced autotetraploid plant and five Indigenous apomictic tetraploid (2n = 40) species. | Novo et al. 2019 |

| Ranunculaceae | Ranunculus | R. auricomus | Determine the effect of hybridization and ploidy level on the male and female sporogenesis process. | Barke et al. 2020 |

| Ranunculaceae | Ranunculus | Ranunculus auricomus | Identify the changes in the reproductive mode in homoploid and heteroploidy hybrid plants of the Ranunculus auricomus complex. | Hojsgaard et al. 2014 |

| Ranunculaceae | Ranunculus | R. auricomus, R. cassubicifolius y R. carpaticola | Crosses between different species with different ploidy levels are performed to evaluate whether it is possible to introgress apomixis. | f & Temsch 2009 |

| Ranunculaceae | Ranunculus | R. auricomus | To know the genetic variation between sexual diploids and apomictic polyploids. | Paun et al. 2006 |

| Ranunculaceae | Ranunculus | R. notabilis, R. carpaticola y R. cassubicifolius | Compare the accumulated mutations and genetic divergence between apomictic and sexual species of the Ranunculus auricomus complex. | Pellino et al. 2013 |

| Ranunculaceae | Ranunculus | R. kuepferi | Explore the relationship between polyploidy and apomixis in an altitudinal gradient. | Schinkel et al. 2016 |

| Ranunculaceae | Ranunculus | Ranunculus auricomus | Investigate F2 hybrid plants generated by manual crossing, where both or one parent had apospory before. | Barke et al. 2018 |

| Ranunculaceae | Ranunculus | R. carpaticola, R. cassubicifolius, R. notabilis, R. variabilis | To shed light on intraspecific ITS nrDNA variability in closely related but morphologically diversified taxa of the Ranunculus auricomus complex in Central Europe. | Hodac et al. 2014 |

| Rosaceae | Amelanchier | A. erecta, A. laevis | Establish the relevance of apomixis and hybridization in the genus. | Campbell & Wright 1996 |

| Rosaceae | Describe the distribution of apomixis and ploidy across the Rosaceae family. | Dickinson et al. 2007 | ||

| Rosaceae | Rosa section Caninae | R. caesia, R. rubiginosa, R. sherardii, R. villosa | Perform interspecific crosses between different ploidy levels to evaluate the reproductive mode, ploidy, and genomic composition of hybrids. | Nybom et al. 2006 |

| Rosaceae | Rubus | Investigate the origin of stable apomictic species and their genetic diversity. | Sarhanová et al. 2017 | |

| Rosaceae | Rubus subgenus Rubus | Evaluate the usefulness of ITS in reconstructing evolutionary pathways in apomictic genera. | Sochor et al. 2015 | |

| Rosaceae | Amelanchier | Understand the role of diploids in polyploid diversification and study the species-delimitation problem in the genus. | Burgess et al. 2015 | |

| Rosaceae | Sorbus subgen. Tormaria | S. x decipiens | Investigate hybrids derived from crosses between Sorbus aria agg. and Sorbus torminalis. | Feulner et al. 2023 |

| Rosaceae | Sorbus | Investigate the evolutionary relationships among Sorbus taxa. | Robertson et al. 2010 | |

| Rosaceae | Sorbus | Elucidate evolutionary relationships among the study taxa and determine the breeding systems within the Sorbus complex. | Hamston et al. 2018 | |

| Rosaceae (subf. Maloidea) | Study the reproductive mode of Amelanchier. | Campbell et al. 1991 | ||

| Describes the theory of gen effect: genomic collision and apomixis. | Carman 2001 | |||

| Review the causes that lead to geographical parthenogenesis in plants. | Hörandl 2006 | |||

| Review the origin of apomixis in natural plant populations. | Hojsgaard & Hörandl 2019 | |||

| Review the actual hypotheses of geographic parthenogenesis. | Hörandl 2009 |

Many studies cited in Table 1 aimed to investigate the inheritance of apomixis by performing artificial crosses between individuals with different ploidy levels and reproductive modes. Therefore, it is relevant to note that although apomixis is the least common phenomenon, it is of great interest, especially in agriculture. For this reason, a summary of the origin of natural and synthetic apomixis is given.

Some general patterns derived from the study reviewed are: 1) all apomictic lineages tend to have a diploid sexual counterpart, either recent or ancestral 2) gene flow between apomictic and sexual populations commonly occurs in the genera Pilosella, Taraxacum, Rubus, Boechera and Ranunculus, suggesting the relevance in these genera of purging asexual genomes with accumulated deleterious mutations to provide new genetic variation to apomictic populations and ultimately produce new apomictic lineages. Consequently, when trying to determine the origin of an apomictic lineage, it is found that it comes from the hybridization of some sexual taxon with another apomictic. This situation is a significant impediment to discern from where the initial apomictic lineages have arisen, whether diploid or polyploid (Koch et al. 2003, Grusz et al. 2009, Sochor et al. 2015, Sarhanová et al. 2017).

Under natural conditions, hybridization in combination with polyploidy appears to be a natural route to asexuality, which in turn is considered an escape route for sterile hybrids, allowing their maintenance within natural populations (Bicknell et al. 2000, Paun et al. 2006, Hörandl 2010, Hojsgaard et al. 2014). A common topic related to polyploidy and apomixis is geographic parthenogenesis, which suggests that organisms with these characteristics are more tolerant and adapted to climatic regions with higher elevations and latitudes, as well as having broader distributions than their sexual relatives (Kearney 2005, Hörandl 2006, 2009, Thompson & Whitton 2006, Hörandl et al. 2008, Schinkel et al. 2016).

It is worth mentioning that there is a bias in the study of apomixis and polyploidy due to their great potential to satisfy the future nutritional demands of humanity (Toenniessen 2001). Many crops are polyploid due to intentional crosses, and such hybridization often increases the vigor or yield of these crops (Renny-Byfield & Wendel 2014).

How is apomixis inherited? Usually, intraspecific and interspecific hybridizations have been carried out between individuals with different ploidy levels and reproductive modes (i.e., sexual reproduction vs. apomixis) to evaluate and compare their effects as well as to determine the mode of inheritance of apomixis (Table 1, Tas & Van Dijk 1999, Van Dijk et al. 1999, Bicknell et al. 2000, Schranz et al. 2005, Hojsgaard et al. 2008, 2014, Hörandl & Temsch 2009, Barke et al. 2018, Feulner et al. 2023, Mártonfiová et al. 2007, Nybom et al. 2006). To evaluate the causes of apomixis, it is necessary to distinguish the effects of ploidy and interspecific hybridization, which is possible in taxa that show apomixis in a diploid state, as occurs in the Boechera holboellii complex, Potentilla argentea and Hierochloe australis (Beck et al. 2012, Lovell et al. 2013). Boechera divaricarpa is an apomictic diploid species, and when it is crossed with a sexual diploid, it generates fertile triploid progeny that is potentially apomictic, highlighting that apomixis in Boechera is not given by a single locus or factor causing "apomixis" (Schranz et al. 2005). The diploid apomictic condition is transmitted through haploid pollen (infectious asexuality) within a single generation, and polyploids can form through multiple pathways (Mau et al. 2021).

In the Ranunculus auricomus complex, apospory emerged spontaneously in the first hybrid generation of two sexually obligate diploid species, and this increased in the F2 where functional apomictic seeds had already developed (Barke et al. 2018, Hojsgaard et al. 2014).

Regarding artificial crosses between species with different ploidy and apomictic capacity, in the genus Boechera, one-third of the crosses showed evidence of apomixis and/or increased ploidy (Schranz et al. 2005). Similarly, in Taraxacum, it has been proposed that several loci are involved in the genetic control of apomixis, (by performing crosses between 2× sexual and 3× apomictics they produced 2×, 3×, and 4× individuals). After that, those individuals can cross again with 2× sexual individuals, resulting in fewer apomictic progeny and more no apomictic progeny with reduced, irregular chromosome numbers (Tas & Van Dijk 1999, Mártonfiová et al. 2007). Therefore, the apomictic of Taraxacum can generate pollen that transfers apomixis to diploid individuals (Baarlen et al. 2000).

Apomixis, in some cases, is controlled by few alleles, so it is suggested that individuals with genome duplications provide the necessary number of these alleles for apomeiosis to occur, in addition to buffering against deleterious mutations in gametes and somatic cells (Bicknell et al. 2000, Grimanelli et al. 2001, Sharbel et al. 2009). For example, the Anachyris subgenus of Paspalum has at least three sexually self-incompatible diploid species, as well as apomictic tetraploid representatives of autopolyploid origin (Hojsgaard et al. 2008), suggesting that apomictic alleles are present in diploids and that their expression depends on ploidy level (Quarin et al. 2001).

Genes involved in natural apomixis. Interspecific hybrids or specific hybrids within agamic complexes are widely studied in the context of segregation of apomixis (apomeiosis, parthenogenesis and functional development of endosperm; Fiaz et al. 2021). Although the genes controlling the various components of apomixis have already been identified, the genetic mechanism of asexual reproduction is complicated in nature and is still not sufficient to explain the entire apomictic phenomenon (Fiaz et al. 2021, Niccolo et al. 2023). Therefore, knowing the genes controlling the sexual pathway may be another way to develop apomixis (Fiaz et al. 2021). Many specific genes that act on parthenogenesis control have been described, such as ASGR-BABY BOOM-like (ASGR-BBML), BABY BOOM1 (BBM1), LOSS OF PARTHENOGENESIS (LOP), PARTENOGENESIS (PAR) genes from apomictic dandelion that triggers embryo development in unfertilized egg cells. Others like Somatic Embryogenesis Receptorlike Kinase (SERK) and MSP1 control somatic embryogenesis. On the contrary, some genes, depending on their homozygous or heterozygous condition, can promote sexuality or apomixis, such as the APOLLO gene (Fiaz et al. 2021, Hojsgaard & Hörandl 2019, Underwood et al. 2022).

Genetic analysis of apomixis inheritance in cereals, grasses, and related genera, i.e., Tripsacum, Pennisetum, Panicum, Bracchiaria, and Paspalum, detected a single chromosome responsible for inducing apomixis. However, the transfer of such chromosomes has been difficult (Mieulet et al. 2016, Fiaz et al. 2021).

In Asian apomictic citrus fruits, a minimum inverted repeat transposable element (MITE) in the promoter region of CitRWP was found to confer an apomictic phenotype responsible for dominant citrus polyembryony. This insertion was estimated to have arisen in the early Pleistocene in an ancestral population and spread to other mandarins, oranges, grapefruits, and lemons (Wang et al. 2017, Wu et al. 2021). Interestingly, repeat transposable element (MITE) insertion in the promoter was also identified in dandelion and hawkweed (Underwood et al. 2022).

Finally, Niccolo et al. (2023) extensively reviewed the expression of genes between sexual and apomictic conditions. They found a differential gene expression between both groups concerning several endogenous effectors (such as small RNAs, epigenetic regulation, hormonal pathways) that may contribute to the appearance of apomixis.

Synthetic apomixis. Apomixis can potentially preserve hybrid vigor in economically important plant genotypes for multiple generations, and synthetic apomixis has been suggested to fix hybrid vigor. As described above, the emergence of apomixis requires three modifications of the sexual pathway to ensure the growth of viable and apomictic fruits: 1) the bypassing of meiotic cell division, 2) the parthenogenetic establishment of an embryo, and 3) the successful development of the endosperm (Barke et al. 2018, Fiaz et al. 2021). Hojsgaard & Hörandl (2019) noted that hybridization could only affect a component of apomixis, such as the formation of an unreduced embryo sac. Still, the other two steps corresponding to parthenogenesis and the endosperm formation would remain unaffected. d'Erfurth et al. (2009) managed to create a genotype called MiMe ("Mitosis instead of Meiosis") as a first step to identify the genes related to apomixis and then try to generate synthetic apomixis genotypes. For example, “apomeiosis” involves the omission or deregulation of meiosis, resulting in a mitotic-like division that prevents ploidy reduction. Three features distinguish meiosis from mitosis: (i) a succession of two rounds of division after a single replication, (ii) pairing and recombination between homologous chromosomes, and (iii) cosegregation of sister chromatids in the first division. By identifying and bringing together three genes that modified these characteristics (OSD1, ATSPO 11-1, and ATREC8), they created a genotype in which mitosis replaces meiosis without affecting subsequent sexual processes. Later, Mieulet et al. (2016) showed that additional combinations of mutations can turn Arabidopsis meiosis into mitosis by replacing SPO11-1 with other recombination initiation factors (PRD1, PRD2, or PRD3/PAIR1) and that a combination of three mutations in rice (Oryza sativa) efficiently turns meiosis into mitosis too. They also identified the functional homolog of OSD1 in rice (OsOSD1), suggesting that it could be identified in other cereals.

Synthetic apomixis achieved with MiMe has disadvantages, such as doubling ploidy in each generation, generating low fertility, and a limited apomixis induction rate in rice. These problems have been solved with the heterologous expression of the dandelion PAR gene, effectively producing clonal seeds with fixed genotypes, which remained stable during the three generations analyzed (Song et al. 2024). The same expression of dandelion PAR in lettuce (Lactuca sativa) egg cells induced haploid embryo-like structures without fertilization (Underwood et al. 2022, Song et al. 2024). Recently, the MiMe system could be established in inbred tomatoes through mutation of SlSPO11-1, SlREC8, and SlTAM (Wang et al. 2024).

The genetics, genomics, and epigenetic modifications that promote apomixis in flowering plants are widely studied. In contrast, studies on apomixis induced by gene editing techniques, i.e., CRISPR/Castem, are in an early stage, as only a few reports have been published, like those done with rice (Fiaz et al. 2021). Genomic alteration employing genome editing technologies (GETs) like clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) for reverse genetics has opened new avenues of research in the life sciences, including for rice grain quality improvement (Fiaz et al. 2019). As has been done with rice, the disadvantages presented with the MiMe and with CRISPR/Cas9 have been attempted to be solved with the “fix strategy” (Hybrid Fixation) with genes that promote the development of the “auto endosperm,” which can solve the problem of low fertility (Fiaz et al. 2021). Circumventions of key imprinting and/or dosage barriers in the endosperm will facilitate the engineering of apomixis technology (Spillane et al. 2004).

Evolutionary relationships between hybrid, polyploid, and apomictic species. When sexual and apomictic plants coexist in sympatry, hybrid swarms can form; for this reason, apomictic groups represent a complex reticulated network of sexual species, stable apomictic lineages and their hybrids with a large variation of genotypes and phenotypes. This variation complicates the taxonomic denomination of such apomictic lineages (Majeský et al. 2015, Majeský et al. 2017, Hamston et al. 2018). In the review by Kolař et al. (2017), it was found that many species contain odd-ploidy cytotypes (3×, 5×, 7×, 9×), which may play an important role in polyploid evolution as mediators of gene flow and recurrent polyploid origins. They also found that species in which odd-ploidy cytotypes are dominant exhibit strong if not exclusive, asexual modes of reproduction, and although their hybrid origin has only been confirmed occasionally, asexual reproduction would facilitate their establishment (Paun et al. 2006, Robertson et al. 2010). Apomixis is generally associated with ploidy (4× or more). However, there are genera where apomixis occurs in diploids and triploids, such as Boechera (Dobes et al. 2007). Diploid apomictics can infect asexually through haploid pollen (Mau et al. 2021). In genera such as Pilosella, Taraxacum, Rubus, Boechera, and Ranunculus, a higher gene flow between apomictics and sexuals has been documented (Sarhanová et al. 2017). Boechera and Alchemilla are genera that show complex evolutionary relationships due to reticulate hybridization and apomixis. Interspecific hybridization is widespread in the former, and sexual species tend to hybridize between them. Apomictic hybrids may also be backcrossed with sexual individuals. Alchemilla presents unresolved taxonomic relationships and a complex taxonomy, although it has many taxa almost exclusively apomictic and only a few with sexual reproduction (Majeský et al. 2017).

One consequence of the interaction among distinct cytotypes is the production of intermediate cytotypes (i.e., triploids), generally at low frequencies. However, triploids may promote the coexistence of multiple cytotypes through a triploid bridge, so understanding the role of triploids is crucial to understanding the dynamics of mixed-cytotype populations (Moura et al. 2020). It is known that triploids are found more frequently where diploids of different species are sympatric and where diploid hybrids occur (Burgess et al. 2015).

Hybridization in completely apomictic populations requires that fertile pollen and reduced egg cells are produced by natural apomicts (Tas & Van Dijk 1999). In Taraxacum, the male meiosis of triploids is predominantly reductional, leading to more than 90 % infertile gametes. Still, the pollen of tetraploid hybrids was reduced and is diploid (Baarlen et al. 2000). However, both can form new triploid apomictic lineages (Mártonfiová et al. 2007). Triploids can arise in two ways: from the fertilization of unreduced eggs by reduced sperm or through the fertilization of reduced eggs of diploids by reduced sperm of tetraploids (Baarlen et al. 2000, Dickinson et al. 2007).

In Boechera, some apomicts produce predominantly unreduced pollen, with considerably high quality, and other triploid lineages are apomictic and produce large quantities of non-functional pollen, but with artificial crosses, they were able to produce tetraploid offspring which have low frequency in natural populations (Tas & Van Dijk 1999, Dobes et al. 2007). It is necessary to know the function of these tetraploids in Boechera since in Taraxacum they help to generate new triploid lineages (Schranz et al. 2005).

In the case of Pilosella, the quality of pollen depended more on the cytotype than on the reproductive mode or its hybrid origin since pollen of lower ploidies 3× and 5× was of lower quality, and this improved as the ploidy increased (Rotreklová et al. 2016). In Amelanchier, the percentage of apomictic seeds increased according to ploidy in di, tri, and tetraploids (Burgess et al. 2015).

If pollen is not needed to form the endosperm, as in many Asteraceae, triploid apomictic lineages can be established quickly, as in Erigeron, Hieracium, and Taraxacum (Hojsgaard & Hörandl 2019). On the contrary, an important barrier to gene flow between cytotypes is the likely deviation from the normal 2m:1p genome ratio (maternal genome: paternal genome) during endosperm formation, as has been suggested for Ranunculus (Hörandl & Temsch 2009, Paule et al. 2011). However, in brambles, they seem to have a relaxed pressure to maintain the normal endosperm equilibrium number 2m:1p, which can vary up to 8m:1p or sometimes have autonomous development (Sarhanová et al. 2017).

The most studied apomictic species complex with reticulate relationships is the Ranunculus auricomus, which comprises approximately 800 apomictic microspecies traditionally grouped into four morphological groups (Majeský et al. 2017). It is known that apomixis introgression into sexual populations is limited by ploidy barriers in the R. auricomus complex and, to a lesser extent, by mentoring effects. Therefore, apomixis introgression could only occur if sexuals had the same ploidy level as apomictics and if in interploidal crosses, there was a relaxation of endosperm balance or autonomous endosperm production (Hörandl 2009).

All apomictic plants appear scattered at the tips of phylogenies and are thought to be evolutionarily young even though the estimation of their ages is biased by possible reversals from apomixis to sexuality (Pellino et al. 2013). For example, Limonium dufourii is a triploid apomictic species that could be considered a deadline because it is self-incompatible and highly sterile; as a consequence, it presents a strong genetic population differentiation (Palop-Esteban et al. 2007). However, although lineages have low fertility, they are not necessarily doomed to extinction because perennial plants can persist for several years (Schranz et al. 2005).

Obligate apomixis and the formation of unreduced male gametes as an evolutionary advantage for the propagation of apomixis help to escape from meiotic sterility because of interspecific hybridization (Matzk et al. 2003). For some tetraploids, the gametophytic apomixis, pollen fertility, and SC (self-compatibility) will combine to improve their fecundity and increase their abundance (Dickinson et al. 2007). Meiosis and pollen production are expected to be more stable in tetraploids, and diploid pollen will be available for pseudogamy (Hojsgaard & Hörandl 2019).

Comparison between sexual species and apomictic polyploids. Another type of study compared the process of meiosis and mitosis between organisms with variation in ploidy level and reproductive mode, which presumably have undergone hybridization processes or, in the best of cases, have been confirmed (Baarlen et al. 2000, 2002). In Ranunculus, megasporogenesis (egg formation) and microsporogenesis (pollen grain production) were compared between diploid and polyploid hybrids, finding that hybridization affects the meiosis of megasporogenesis to a greater extent than microsporogenesis (Barke et al. 2020). In Taraxacum officinale unexpectedly high levels of genetic variation have been found in the apomictic populations. Meiosis was compared between sexual diploid and apomictic triploid plants to find mechanisms that could account for the high levels of genetic variation in the apomicts. The authors found a low level of chromosome pairing and chiasma formation at meiotic prophase I in the microsporocytes of the triploid apomicts and an incidental formation of tetrads in the megasporocytes of the apomicts (Van Baarlen et al. 2000).

A sympatric population of sexual and apomictic cytotypes of Paspalum contains a higher level of genetic variation than ploidy-uniform populations, which highlights hybridization as a process that increases the genetic variation of apomictic cytotypes and creates new apomictic lineages (Majeský et al. 2017). Likewise, repeated backcrossing of apomictic derivatives with parental Sorbus taxa is responsible for generating new apomictic taxa (Robertson et al. 2010).

In dandelion contact zones, hybridization between apomictic and sexual plants generates greater genotypic and morphological diversity of apomictics, and the accumulation of somatic mutations was found (Majeský et al. 2015). In Boechera, the diploid apomicts showed high heterozygosity as a result of the combination of disparate genomes, suggesting that most are of hybrid origin and that hybridization allows the transition to gametophytic apomixis (Beck et al. 2012). Polyploidy may favor the rapid accumulation of changes in a short period because more possible mutational sites are available (Pellino et al. 2013). New highly heterozygous species arise from interploidy crosses and can be perpetuated with apomixis or with a more or less mixed mating system (Dickinson et al. 2007).

Facultative apomicts retain the ability to reproduce sexually and produce viable pollen, and therefore, their genotypic variability is often comparable with that of their sexual relatives (Sarhanová et al. 2017). It is proposed that occasional sexuality and recombination could generate high levels of genetic variation within populations and help to differentiate apomictic populations. However, this does not apply to Limonium dufourii due to its self-incompatibility and high sterility, showing a range of moderate to high genotypic diversity (Palop-Esteban et al. 2007).

The divergence between diploids and hexaploids can be attributed to Muller's ratchet (accumulation of mutations in asexuals) since apomicts have been shown to generate appreciable amounts of genetic variation through non-meiotic processes (Paule et al. 2011). Therefore, we expect generally elevated levels of heterozygosity in apomictic individuals relative to the ancestral sexual lineages (Lovell et al. 2013). To analyze the origins of genetic diversity in polyploids, it is necessary to compare the polyploid taxon with its presumed parents or to compare multiple sets of progenies. Neither of these methods is feasible in Limonium dufourii because its parental species are unknown, and it cannot reproduce sexually (Palop-Esteban et al. 2007).

Due to the non-recombinant nature of apomicts (Lovell et al. 2013) and considering apomictic taxa as "young taxa," most of the genetic diversity in obligately polyploid apomictic taxa is obtained at the time of species formation through hybridization (Palop-Esteban et al. 2007).

Finally, many other study systems could improve the understanding of the evolution of these three phenomena. For example, in the genus Fuchsia, F. microphylla and F. thymifolia, which are gynodioic shrubs described as diploid, female flowers produce fruits under conditions of isolation from pollinators; however, there is a lack of molecular evidence confirming the presence of apomixis (Cuevas et al. 2014). It is worth mentioning that both species coexist sympatrically, and hybridization between these two species has recently been confirmed, making it a good model for monitoring polyploidy and apomixis in hybrid individuals (Cervantes-Díaz et al. 2024).

In conclusion hybridization is commonly recorded without the emergence of polyploidy and apomixis. However, this does not exclude the possibility that they accompany it because these last two phenomena are scarcely evaluated in most angiosperms. In the case of the so-called “apomictic species”, this classification can often depend on the evaluated sample size, as well as the technique used for its identification, because in many cases, apomictic species are not obligate but rather facultative, along an asexual-sexual gradient. However, polyploidy and apomixis are strongly related because both phenomena imply a dysregulation of the sexual reproductive pathway. The hypotheses that try to explain the conjunction of these phenomena included study cases that support them and, in other cases, do not because of the high diversity of possibilities in the few species studied. Therefore, future studies should expand to succeed in finding a general pattern.

Few studies have proposed to corroborate whether interspecific hybridization can promote the emergence of apomixis and polyploid. Still, it is evident that once these lineages are established, they can continue to hybridize with their own parents or with other taxa, generating more lineages. In this way, the complex relationships established between these systems make it difficult to recognize “species” to such an extent that most authors prefer to refer to their study populations with terms such as “taxa, lineages, complexes or sections”. It is important to note that for this reticulated evolution to occur, apomictic hybrids, whether polyploid or not, must produce some proportion of viable pollen that will be their only way to contribute to generating new lineages.

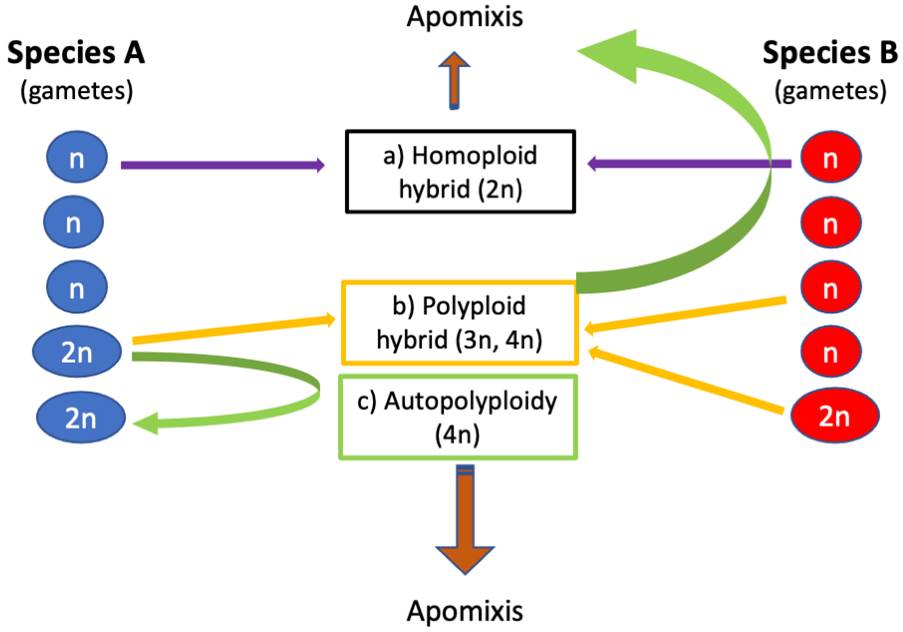

Some evolutionary routes related to the three phenomena assessed in this review are presented in Figure 1. For example, when a reduced gamete (species A) joins with an unreduced gamete (species B), a polyploid hybrid is instantly formed because of the divergence of the parent genomes. In another case, we see that diploid species A could become autotetraploid (4×); therefore, apomixis could develop. Finally, if two diploid species, A and B, hybridize, they can give rise to a diploid hybrid that can suffer irregularities in meiosis, leading to the appearance of apomixis, which depends on whether pollen is required to form the endosperm and could lead to the formation of polyploid or diploid apomictic hybrids. In the event that diploid hybrids do not become apomictic immediately after hybridization, they can increase their percentage of unreduced gametes that, when fusing with gametes of some other species, would give rise to a polyploid hybrid that could develop apomixis.

Figure 1 Different routes from two diploid species (2n) and the production of haploid (n) or non-reduced gametes (2n) and their relationship with the emergence of hybridization, apomixis, and polyploidy. Although apomictic diploid species are also known, these usually present a history of hybridization and polyploidy in their previous lineages.

Related to hybridization, apomixis, and polyploidy, there are other important factors to consider, such as the 2:1 genetic contribution (maternal: paternal) in the formation of the endosperm since it has been shown that when this ratio is disrupted, the seed’s viability is reduced. In addition, it has been reported that many species lose self-incompatibility by developing an apomictic capacity, which many consider to be an evolutionary “cul-de-sac” destined to extinction due to a lack of genetic variation. Finally, we concluded that the knowledge of these three phenomena is still very limited due to the difficulty in detecting them and their enormous variation, their potential for combination, and the numerous orders in which they can occur in plants. However, the development of metagenomics will most likely bring significant advances in the short and medium term.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)