Introduction

The trophic aspects of ecology, including ecosystem energy flow, began to be formally studied as early as the 1940's. The basic rationale is that organisms are connected to each other through feeding relationships and all together constitute a functional unity (ecosystem) (Lindeman 1942). This simple idea has resulted in numerous field observations and hypothesis testing over the last 70 years (Sobczak 2005).

One of the first attempts to describe ecological systems was to parallel the concept of biological communities with that of organisms. Clements (1916, 1936) conceived plant communities as super-organisms that develop from early stages until reaching maturity or climax. This hypothesis was rejected by most scientists arguing that, far from being an organismic entity, communities are composed by random associations of locally adapted species (Gleason 1926). Also rejecting Clements' analogy, Tansley (1935) stated that animals and plants, in combination with physical factors, constitute a functional distinctive unit that he named "ecosystem." Likewise, Elton (1927) introduced two concepts: 1) "food chain" regarding to the feeding relationships among organisms, which comprise linear elements of the "feeding cycle", currently known as "trophic web"; and 2) "numerical pyramid", used to describe the organization of communities with larger organisms feeding upon more abundant, smaller-size preys.

Later, populations and communities were considered thermodynamic systems, interchanging matter and energy that can be represented by equations (Lotka 1925). However, the idea of the ecosystem as a transformer of thermodynamic energy was first introduced by Lindeman (1942). By coupling Tansley's and Elton´s concepts, Lindeman described food chains as a series of steps that he called "trophic levels". He visualized Elton's numerical pyramid as an energy transformation hierarchy, suggesting that a certain amount is lost at each step due to the inefficiency of biological systems to transform energy (Lindeman 1942).

The ecosystem concept began to be more widely used during the 1950's. At the same time, there was agreement that studying flows of energy and matter within ecosystems allowed characterization of their structure and function. On this basis, Odum (1953 1968) postulated the universal energy flow model, which can be applied to every living system (individual, population, or trophic group). Odum's work on ecosystem energetics demonstrated that it is possible to generalize at the community level without having information about lower levels of the organization.

During the 1960's, the idea that matter and energy flow through feeding interactions and nutrient cycles within and between ecosystems was widely acknowledged. The understanding of ecosystem structure and functioning, however, required specific data on energetic transformations, as well as energy and matter flow measurements (Odum 1968). Such demand began to be satisfied by detailed studies on hydrology, nutrient cycling, and energetics in fresh waters basins. Lakes, in fact, served as natural laboratories (well-limited boundaries) where many of current ecological theories were developed (Likens 1985). Current research focuses on generating ecosystem level indicators (Nielsen and Jφrgensen 2013, Arreguín-Sánchez 2014) and on identifying ecosystem organization global patterns, structure, and function (Jφrgensen et al. 2010, Barange et al. 2011, Coscieme et al. 2013). Several ecosystem theories have been compiled and discussed in excellent books, such as the one by Jφrgensen and Müller (2000).

After 64 years, the trophic ecology research field formalized by Lindeman is still important to scientists (Sobczak 2005). In this contribution we address how this field has grown since the formulation of Odum's universal model of energy flows. We also examine theoretical aspects relative to the trophic flow concept at the ecosystem level. We have adopted the laws of thermodynamics to describe some generalities of trophic flows and their relationship with the structure, function, and development of ecosystems. We further discuss the advantages of studying trophic flows under the context of living resource management.

Matter, energy, and the concept of trophic flow

Our biosphere contains a particular manifestation of matter popularly known as "living matter." During biological evolution, matter is organized in structures of increasing complexity, from inorganic compounds up to multicellular organisms (Addiscott 2010). This organization demands a constant supply of energy, most of which is originated by the sun. As structures are organized and increase in complexity, their components are more closely associated with each other. In this sense, ecosystems result from a combination of interdependent parts that function as a unique system and require energy inputs to produce outputs. Fundamental parts of an ecosystem can be identified by their structural and functional features (Odum 1953).

The Earth is an open system of energy yet relatively closed to extraterrestrial matter inputs. The sun is an unlimited resource of energy that most ecosystems utilize to preserve their self-generated and limited energy, although there are some exceptions such as hydrothermal vents (Micheli et al. 2002). While energy flows unidirectionally, matter is continuously recycled and retained as nutrients in the system. Plants transform solar energy into chemical energy, which is transferred to the entire ecosystem through the food chain (Odum 1953). Fungi and bacteria recycle matter and reduce dead organic matter into inorganic matter, which is newly available for primary producers. Dead organic matter (detritus) and inorganic nutrients are the ecosystem´s energy reserve. Movement of matter and energy within the ecosystem is called "flow"; thus, the flow of solar energy feeds the cycles of matter in the biosphere, and it also controls biogeochemical cycles. In thermodynamic terms, there are four conditions for the existence of an ecosystem: 1) energy source, 2) matter recycling, 3) energy reserve, and 4) energy conversion and transfer rates through trophic interactions among species (Odum 1968).

Energy and matter are distributed in the ecosystem following multiple routes that comprise an energetic web. This web is formed by living organisms and inanimate parts of the ecosystem, although not all flows can be seen as a biological part of the ecosystem (Kay 2000). The existence of other energy flows that influence the biotic environment, such as wind and ocean currents, will not be considered here.

We propose the following definition: trophic flow is the transfer of nourishment that occurs among organization levels, beginning with individuals and moving through the ecosystem as part of a discernible energetic circulation scheme. This concept is not limited to trophic relationships, but includes flows of non-living matter towards biological systems; for instance, the energy flowing from nutrients (inorganic material in the physical substrate) towards plants.

Revisiting Odum's universal energy flow model

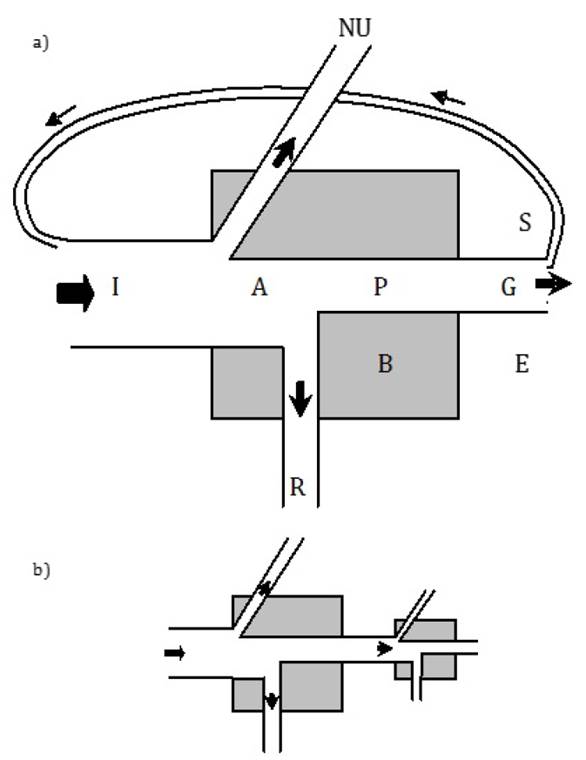

The Odum's universal energy flow model represents the basis for a general explanation of ecosystem trophic flows (Odum 1968). This model (Figure 1a) could be applied from the individual to the ecosystem level (Odum 1953). It portrays the system (individual, population, trophic level, or ecosystem) biomass (B), energy inputs (I), and outputs. For autotrophs I is solar radiation, and for heterotrophs I is ingested food. Since not all the energy supplied is utilized, the lost part is labeled as "NU." The assimilated energy (A) is known as gross production. Part of A is used for system structural maintenance, that is the respiration (R), and the other part is transformed into organic matter (P), known as net production. Component "P" is the energy available for other individuals (predators) or trophic levels. Individuals use part of the net production for somatic growth (G) or, in the case of populations or trophic levels, for biomass accumulation. Another part of net production can be stored (S) at individual level in the form of organic compounds of higher energetic content (lipids) or, at ecosystem level, as a nutrients deposit or detritus. Some production can be excreted by individuals or, analogously, exported from the ecosystem (E) (Odum 1968).

The energy inputs and outputs from the universal model can also be linked to represent subsystems from different ecological hierarchies or ecological processes (Schlesinger 2006, Sukhdeo 2010, Li et al. 2013) (Figure 1b). Compartments receiving energy in a subsystem are of smaller size since they contain less energy. It is easy to connect at least two models to represent trophic flows among biological components. In autotrophs, during the gross primary production, the solar energy is converted into chemical energy through photosynthesis and some of it is lost as heat during the process. Autotrophs also seize part of the absorbed energy for respiration and growth; the remaining energy, called net primary production, is available for the next trophic level (Odum 1953).

Figure 1. Energy Flow Universal Model by E. P. Odum (1968). a) single model and b) two subsystems connected. I: energy input, A: assimilated energy, NU: non used energy, R: respiration, P: production, G: somatic growth, B: biomass, S: energy stored, E: energy exported.

Ecosystem thermodynamics

In order to understand the energy and matter flow dynamics in ecosystems, we need to examine some fundamental physical laws. The first law of thermodynamics, also known as energy-mass conservation law, states that neither energy nor matter can be created or destroyed; rather, the amount of energy lost in a steady state process cannot be greater than the amount of energy gained (Kay 1991). For instance, the biological conversion of solar energy into chemical energy must be balanced, as expressed in Odum's model, such that the sum of all outputs is equal to the sum of inputs (Odum 1968).

The second law of thermodynamics, also known as law of entropy, states that any change of energy from one form to another implies an irreversible loss of useful energy in form of heat, which increases the entropy or disorder of the universe. In some systems, entropy remains constant but never decreases; only irreversible processes produce entropy (Schneider and Kay 1994). An example of the second law in ecology is metabolism, in which a set of chemical reactions in an individual transforms organic matter into a more useful component. However, the cost of this conversion includes respiration, which is energy unavailable neither to individual nor to others in the food web (Patten 1985).

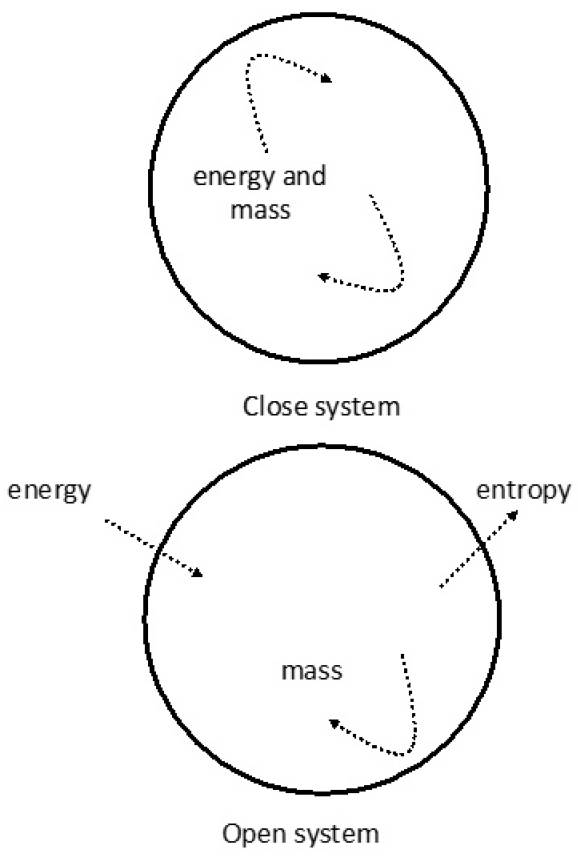

This example raises the question that biological systems are in contradiction with the second law of thermodynamics. Thermodynamic laws are based on what is observed in closed and isolated systems, i.e. there is no mass and/or energy interchange with the environment. This kind of systems tends to reach a thermodynamic equilibrium; for example, the maximum value of entropy with no additional energy dissipation (Woolhouse, 1967, Wilson 1968). Ecosystems are neither isolated nor closed systems when considering the solar energy input (Odum 1953).

General Systems Theory (von Bertalanffy 1950), Cybernetics Theory (Weiner 1948), and Communication Theory (Shannon and Weaver 1949) provided the basis for the understanding of natural systems. Von Bertalanffy (1950) stated, "An organism is not a conglomerate of elements but an organized and integrated "system." Cybernetics Theory proposed that ecosystems are selfregulated systems, and Communication Theory was used to understand that, within ecosystems, energy might follow multiple routes. Schrödinger (1944) first recognized that living systems are not in thermodynamic equilibrium and that they are only able to exist amidst a continuous flow of energy and mass. He proposed the concept of negative entropy or negentropy, meaning that biological systems tend to show an increased complex organization with a continuous flow of energy. This concept was further developed by Prigogine (1978), who stated that non-equilibrium systems are characterized by irreversibility. For example, ecosystems, weather, and solar radiation are ruled by thermodynamic laws, but their boundaries are so diffuse that it is impossible to establish equilibrium. They reach a certain organization level depending on the energy input, and the bigger the input the greater the organization, thus resulting in the release of entropy (Johnson 1981) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Difference between close and open systems. In a close system, there is no energy or mass interchange with its environment. When the energy or mass are totally used, the system reaches its thermodynamic equilibrium, no more changes occur within the system and the entropy is at top. In an open system, the thermodynamic equilibrium is never reached due to the constant flow of energy and the release of entropy.

Non-equilibrium conditions imply a constant interchange of energy and entropy between the system and its environment, and a tendency towards a greater organization. This demands a constant flow and use/dissipation of energy, which is possible through dissipative structures (Prigogine 1978, Nicolis and Prigogine 1977, 1989). Systems presenting dissipative structures actively acquire energy through a negative gradient in relation to their environment. The system´s diffuse boundaries prevent thermodynamic equilibrium and energy is obtained at a greater rate than it is dissipated. In ecology, this is equivalent to the production/respiration ratio. Living organisms continuously consume energy for maintaining life and order in their energetic circulation patterns; thus, life tends to a minimum entropy state. Since entropy produced by the biosphere dissipates to the universe, no violation of the second law of thermodynamics occurs (Johnson 1981, Kay and Schneider 1992, Schneider and Kay 1994, Schneider and Kay 1997, Addiscott 2010, Tiezzi 2011) (Figure 2).

A useful concept in the topic of ecosystem development is exergy, which derives from thermodynamics. During any energy transformation, as we noted in the second law of thermodynamics, the quality of energy to perform work is irretrievably lost (Kay 2000). In this context, exergy could be defined as a measure of the maximum amount of work that the system can perform when it is brought into thermodynamic equilibrium relative to an environmental reference state (Brzustowski and Golem 1978, Ahern 1980, Jφrgensen et al. 2005). When this work is performed, exergy decreases and the entropy increases; thus exergy represents the amount of energy degraded in any given energy transformation. We believe that as an ecosystem grows and develops, the efficiency of energy assimilation along the trophic webs increases, thus consuming more exergy. A system with greater exergy moves further from its reference state and further from thermodynamic equilibrium (Fath et al. 2004), which allows a more developed or organized state (Silow and Mokry 2010).

From the thermodynamics point of view, natural selection will favor those individuals that use energy more effectively, channeling it into their own (re)production, and contributing the most to increase the overall system energy degradation (Kay and Schneider 1992). Kay (2000) highlighted the following ecosystem properties as they relate to energy circulation: 1) open systems; 2) nonthermodynamic equilibrium systems; 3) the existence of energy gradients across borders, which are irreversibly degraded in order to maintain the system structure; 4) mass cycles; and 5) a tendency to reach a higher organization as the system moves further from thermodynamic equilibrium. An example of this is the ecological succession phenomenon (Clements 1916).

Trophic flow regulation

Trophic flow regulation is the way in which ecosystems are structured and work. Regulatory mechanisms can have qualitative (structural) or quantitative (functional) effects (Hunter and Price 1992). For instance, an increase in primary producers may foster the abundance of certain herbivores without changing the overall species composition (quantitative). On the other hand, competitive exclusion among species or species invasion could reduce the abundance of one or more species, and thus disrupting the predator-prey balance (qualitative effect) (Fox 2007). Both of these examples would affect how energy circulates among the components of the ecosystem (Menge 1992, 2000).

The solar energy assimilation rate by primary producers may be limited by the availability of phosphorus and nitrogen, which, in turn, depends on energy transference processes among species. This suggests that trophic flows in the ecosystem are regulated by nutrient abundance or "bottom-up" control. For example, limitations to the abundance of lower trophic levels will thus determine the abundance of higher trophic levels (Hunter and Price 1992). Alternatively, if the predator exerts control on its prey and indirectly affects consecutive lower trophic levels, the energy control is known as "top-down", which is the basis for the "trophic cascade" phenomenon (Vanni and Findlay 1990, Strong 1992, Snyder and Wise 2001). Which type of ecosystem energy-control mechanism prevails is a topic of debate among ecologists (Hunter and Price 1992, Power 1992, Strong 1992, Menge 2000, Fox 2007, Faithfull 2011). For instance, Rosemond et al. (1993) measured the production of periphyton communities subjected to artificial fertilization in the presence and absence of foraging snails. Addition of phosphorous and/or nitrogen increased the productivity in all cases, which suggest a bottom-up mechanism. However, the production was limited by the snail predatory activity, which represents a top-down control; production was higher when the community was protected from foraging. This and other studies suggest that ecosystem function is simultaneously controlled by both mechanisms (Carpenter 1988, MacQueen et al. 1989 Hunter and Price 1992, Power 1992, Rosemond et al. 1993). We believe that the central idea of this discussion should not be if higher trophic levels regulate primary producers, but how much regulation occurs; clearly, there is always some degree of bottom-up energy control (Cury et al. 2003), even when top-down effects predominate.

Another type of flow control is known as donor control (Strong 1992). This occurs when resource abundance affects consumer density, but consumers do not affect resource renewability. For example, the leaves falling into a pond may affect local aquatic communities, yet these organisms do not influence in any way the rate of the leaf fall. Donor control is different from reciprocal control, where the consumer does affect the resource replacement rate, which analogously affects the consumer. This can be seen as an extreme case of bottom-up control (Sánchez-Piñero and Polis 2000).

Trophic flow analyses

Ecosystem energetics can be studied from two different perspectives: static and dynamic. The first one consists of describing flows at a specific moment, instantaneously. The second, concomitant with computer technology development, implies the use of mathematical models that simulate trophic circulation between ecosystem components, as well as their structural and functional changes over space and time (Plaganyi 2007).

A widely used approach to better understand ecosystem energetics is that of network analysis, based on economics input-output analysis (Leontief 1951, Agustinovics 1970). This method quantifies the amount of primary material generated by a certain quantity of producers and was first incorporated into ecology by Hannon (1973). Originally, this analysis was known as compartmental analysis, where input was a linear function of flow into specfic compartments. The acceptance of network analysis as they relate to ecosystems began with the influential work of Patten and coworkers (Patten, 1985, 1998), as well as when Ulanowicz and Kay (1991) incorporated these methods into the NETWRK IV software. This methodology is an advance over previous techniques because it includes flow analysis combined with information theory (Field et al. 1989). Currently, network analysis in ecology quantifies the structure and function of trophic webs by evaluating energy-biomass transference, assimilation, and dissipation through flow paths (Baird and Ulanowicz 1989, 1993, Monaco and Ulanowicz 1997, Patten 1998). This type of analysis has been used to quantify ecosystem health and integrity (Kay 1991, Ulanowicz 2000), to evaluate the magnitude of human and natural impacts on ecosystems (Mageau et al. 1998), and to formulate hypothesis of ecosystems organization (Patten et al. 2011).

A network approach in ecology basically consists of four components: 1) analysis of inputs and outputs for quantifying direct and indirect trophic effects of each component on the whole web, and determining the interdependence between them; 2) determination of trophic status and identification of linear food chains by simplifying the web structure, allowing estimates of transfer efficiency; 3) analysis of cycles in order to establish the routes by which a mass unit travels across the trophic web until it returns to its starting point, which implies the estimation of the number of cycles and the percentage of recycled mass; and 4) computation of ecosystem indices (Ulanowicz 1986) which derive from the ecosystem growth and development theory. The most noticeable rates in network analysis are those proposed by Ulanowicz: 1) Total System Throughput (T) or the sum of all flows, which determines the size or growth of the system and characterizes the overall ecosystem activity; 2) Average Mutual Information (I), which measures the heterogeneity at which energy flows within the trophic system; 3) Ascendency (A), which provides information about the size and organization of flows in the system (A=T*I); and 4) Development Capacity (C), which indicates the theoretical limit of development capacity of the food web. As ecosystems develop, A increases. The difference between C and A is called overhead (O), which represents the recovery potential of the ecosystem. The ecosystem rates proposed by Ulanowicz are currently used to evaluate sustainability and vulnerability of ecosystem to external perturbations and they have proved a great potential for management applications (Ulanowicz et al. 2009, Arreguín-Sánchez and Ruiz-Barreiro, 2014).

Current ecosystem models allow the consideration of tropho-dynamics elements of ecosystems to model the response of various populations in space and time (Christensen and Walters 2004, Fulton et al. 2004, Christensen et al. 2014). By using these tools, we can also compare the structure and function of different types of ecosystems under different potentially undesirable situations in terms of biodiversity loss as consequence of overexploitation or environmental changes (Plaganyi 2007).

Another interesting approach for analyzing trophic circulation derives from the emergy concept (Odum, 1988). Emergy (embodied-energy) is the amount of energy used to generate a given product or service, and it is expressed in solar equivalent Joules. The concept has been applied to determine specfic quantities of solar energy required for making a product. A practical application is to quantify the fraction of primary production required to support fishing activities (Pauly and Christensen 1995). Currently, new methods are being developed using emergy "accounting" for ecological and climate change modeling to provide supporting information for policy makers (Franzese et al. 2014).

Conclusions

We believe that one of the future challenges will be to find a practical and simple form to identify which of the trophic flows in the ecosystem contributes in a more significant way to the structure and function of ecosystems, and how many of our resources exploitative practices are modifying these flows. One of the alternative methodologies would be the utilization of models that implicitly consider the trophic relationships between the biotic components of the ecosystem and allow quantification of the trophic flows, whether of matter or energy. If it is possible to find a way to assign a biological and economic value to each one of the flows following some reasonable criteria, we would be able to learn which flows are more important for conservation of the ecosystem integrity and which are the most important flows for the yield of our exploited resources. There is the ideal possibility that the same flows function in both cases; if not, we will rediscover the everyday crossroads of conservation or utilization. It is important to note that if human activities do not sustain healthy ecosystems, humans are in danger of being selected out of the system in the natural selection process.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)