Introduction

The land surface cultivated with bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) in Mexico, in 2019, was approximately 2,370 ha, with an annual production of 120,961.05 t; furthermore, from that annual production, 95,916.75 t were produced in Sinaloa state, 9,000 t in Baja California Sur and 8,370 t in Sonora, mainly (SIAP, 2019). Overall, 16 % of the total production of bell peppers from open-field or greenhouse conditions are exported (SIAP, 2019), mainly to the United States of America and Canada (Reséndiz-Melgar et al., 2010). According to Sánchez-Gómez et al. (2019) bell pepper is the most exported vegetable crop to the United States with 17 % of total horticultural Mexican exports.

The intensive application of mineral fertilizers to horticultural crops is a common agricultural practice that enhances plant production and productivity; however, it also has contributed substantially to ecosystem contamination. For example, nitrogen is the most limiting nutrient in horticultural crop production. Thus, plant growers must apply excessive amount of nitrogen fertilizers to satisfy plant nutritional requirements; for instance, approximately 250-350 units of nitrogen per hectare are required for bell pepper cultivation (Reche, 2010). Nevertheless, most crops generally use 50 % of the nitrogen fertilizers, and the rest may cause environmental threats such as soil degradation, eutrophication, contamination of underground water, and emission of ammonia and greenhouse gases (Spiertz, 2010). Moreover, some agronomical strategies for bell pepper cropping are directed for improving the uptake efficiency of nitrogen fertilizers as well as the water use efficiency of plants, in order to prevent nutrient loss by leaching or lixiviation processes (Rincón, 2003). Consequently, many developing countries face the challenge for implementing alternate agricultural models focused on more sustainable practices, but allowing food production to satisfy a growing world population (Thilagar et al., 2016). Thus, the utilization of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) can serve as an alternative for reducing high application of inorganic fertilizers and for maintaining sustainable agricultural systems, since both PGPR and AMF play a significant role on soil nutrient availability and, therefore, improve plant health and productivity (Jeffries et al., 2003).

The PGPR improve plant growth by inducing the synthesis of phytohormones, suppressing phytopathogens, producing siderophores, fixing atmospheric nitrogen, mineralizing organic phosphorus sources, or increasing nutrient uptake (Ahemad and Kibret, 2014; Park et al., 2017). Moreover, the indole acetic acid (IAA) is the main phytohormone produced by some PGPR (Dell’Amico et al., 2008), whose synthesis is related to either 3-pyruvate (IPA) or indole-3-acetamide (IAM) pathway (Spaepen and Vanderleyden, 2011).

The AMF (Phylum Glomeromycota, Schüßler et al., 2001; now reclassified as Subphyllum Glomeromycotina, Spatafora et al., 2016) establish symbiosis with more than 80 % of terrestrial plants. This symbiosis facilitates nutrient absorption and translocation to plants, since AMF hyphae form a functional network with greater capability to explore soil and forage mineral resources (Van der Heijden and Horton, 2009). Hyphae networks are linked to roots, soil, and associated microflora, and allow the releasing of nutrients from soil particles and facilitate water and nutrient absorption by plants (Smith et al., 2015). In addition, AMF and PGPR may act synergistically for stimulating plant growth by improving nutrient acquisition and inhibiting pathogens. These microbial interactions are crucial in sustainable agricultural systems, which depend on functional biological processes rather than the application of agrochemical inputs, for maintaining soil fertility and plant health (Artursson et al., 2006).

Some studies have shown the benefits of PGPR and AMF for pepper plants; for example, by inoculating bacterial strains such as Bacillus cereus MJ-1, B. macroides CJ-29, and B. pumilus CJ-69 (Joo et al., 2004) or by combining bacteria like Acinetobacter junii with Rhizophagus intraradices and R. fasciculatus (Padmavathi et al., 2015). In addition, the single inoculation of Glomus intraradices (now reclassified as Rhizophagus intraradices; Walker and Schüßler, 2010) and Gigas-pora margarita enhanced the fruit dry weight of eight genotypes of bell pepper when compared to uninoculated plants (Sensoy et al., 2007).

The production of healthy and vigorous seedlings is fundamental in horticulture for improving plant adaptation to field conditions (Diniz et al., 2009). Thus, seedling propagation in nurseries represents the best moment to perform the inoculation of beneficial and effective microorganisms. Moreover, such inoculation guarantees that these microorganisms are in direct contact with the root system without competing with other microorganisms, thus favoring early plant benefits (Anith et al., 2015). Nevertheless, there is limited information about the benefits of PGPR in combination with AMF consortia for improving the growth of pepper seedlings. Thus, this research focused on evaluating the benefits of PGPR and AMF on Bell pepper plants cv. California Wonder under greenhouse conditions.

Materials and methods

Plant material, seed sowing and experimental conditions

Bell pepper seeds cv. California Wonder were used (Distribuidora Rancho Los Molinos S.A. de C.V.), with 89% of seed germination. Seeds were sown in polystyrene trays with 200 cavities, which were cut into 20-cavity sections to establish the experimental treatments. One seed was sown per cavity in a substrate consisted of sand, peat-moss, and perlite (1:1:1 v/v), previously sterilized (121 ºC for 3 h, during two consecutive days). Each experimental treatment was set in polystyrene trays (20-cavity sections each) by duplicate, from which 12 replicates were taken for further analyses. Each cavity with 25 cm3 of substrate, was maintained with one bell pepper seedling. The research was performed under greenhouse conditions (19º 27’ 51” north latitude, and 2240 masl).

Microbial strains, inocula preparation and plant inoculation

All microbial strains (bacteria and AMF consortium) belong to the microbial collection of the Soil Microbiology Department. An arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal (AMF) consortium was utilized. This AMF consortium was previously isolated from the rhizosphere of poblano pepper crops at Puebla State, and integrated by Funneliformis aff. geosporum and Claroideoglomus sp. (Carballar-Hernández et al., 2017). The inoculum was previously propagated in trap cultures under greenhouse conditions by using sorghum and maize plants as hosts; this AMF inoculum consisted of 2,296 spores per 100 g dry soil, as well as of root fragments with 37 % of mycorrhizal colonization.

The bacterial strains P61 (Pseudomonas tolaasii) and R44 (Bacillus pumilus) were utilized, as well as the mixture of both bacteria. Both bacteria were previously characterized as PGPR due to their capability for P-solubilization, and indole-production (González-Mancilla et al., 2017).

Each bacterial strain was grown in nutrient broth at 28 ºC for 72 h, and then centrifuged for 15 min at 7,000 rpm for separating the microbial biomass. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in sterile saline solution (0.85 % NaCl), and centrifuged twice (10,000 rpm) to eliminate the residual liquid medium. Bacterial cell concentrations for P61, R44 and mixed inoculum, were adjusted with sterile saline solution to achieve a bacterial population of 1 × 108 cells mL-1. This bacterial cell number was estimated with the Neubauer chamber, and microscopic counting.

The AMF inoculation was performed at seed sowing by mixing the inoculum with the substrate in a 1:4 v/v ratio. Thus, 5 g of AMF inoculum were applied per plant, equivalent to 100 spores per cavity. Bacterial inocula were applied to 15 days old seedlings (15 days after seed germination) by adding 2 mL (1 × 108 cells mL-1) of the corresponding inoculum directly to the stem base of seedlings.

All treatments were irrigated every three days with 10 % Steiner nutrient solution (Steiner, 1961) with 0.2 dS m-1 electrical conductivity and (mg L-1) 106.2 Ca(NO3)2•4H2O, 31.2 KNO3, 27.0 K2SO4, 49.2 Mg-SO4•7H2O, and 13.6 KH2PO4, adjusting the pH to 6.5 with a solution of 10 % sulfuric acid. Plants were kept under greenhouse conditions for 80 days after inoculation (vegetative stage). The maximum/ minimum average relative humidity was 97.3 % ± 2.8/21.3 % ± 1.4, respectively; and the maximum/ minimum average temperatures were 37.7 ºC ± 7.3/ 9.6 ºC ± 4.1, respectively.

Evaluated variables

After 80 days of microbial inoculation, plants were harvested to evaluate plant height, stem diameter, root volume, number of leaves, leaf area, shoot and total dry weight, photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fo= relationship between variable fluorescence and initial fluorescence), relative chlorophyll content (SPAD units), and arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization. Root volume was measured using the water displacement method (Böhm, 1979), and leaf area was determined with a LICOR portable leaf area meter (LI 3000, Inc. Lincoln, NE, USA). The dry biomass was obtained by drying (70 ºC for 72 h) leaves, stems, and roots, and weighing in an analytic scale (Sartorius, Model Analytic AC 210S, Illinois, USA). The photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fo) and the relative chlorophyll content (SPAD units) were measured with a fluorometer OS-30p+ (Opti-Sciences) and a Spadmeter model 502 (Minolta, Japan), respectively, by taking readings from the middle part of the most recent mature leaf.

Total mycorrhizal colonization (TMC) was measured by the clearing and root staining procedure (Phillips and Hayman, 1970), and by estimating the colonization percentage through microscope observations (Biermann and Linderman, 1981).

Experimental design and data analyses

A 4 × 2 factorial experiment was set with four levels of bacterial inoculation (P61, R44, bacterial mix, and uninoculated control) and two levels of mycorrhizal condition (non-AMF and AMF inoculation). The eight treatments with 12 replicates each were distributed in a completely randomized design. Data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance and the mean comparison test (LSD, α = 0.05) (SAS Institute, 2002).

Results

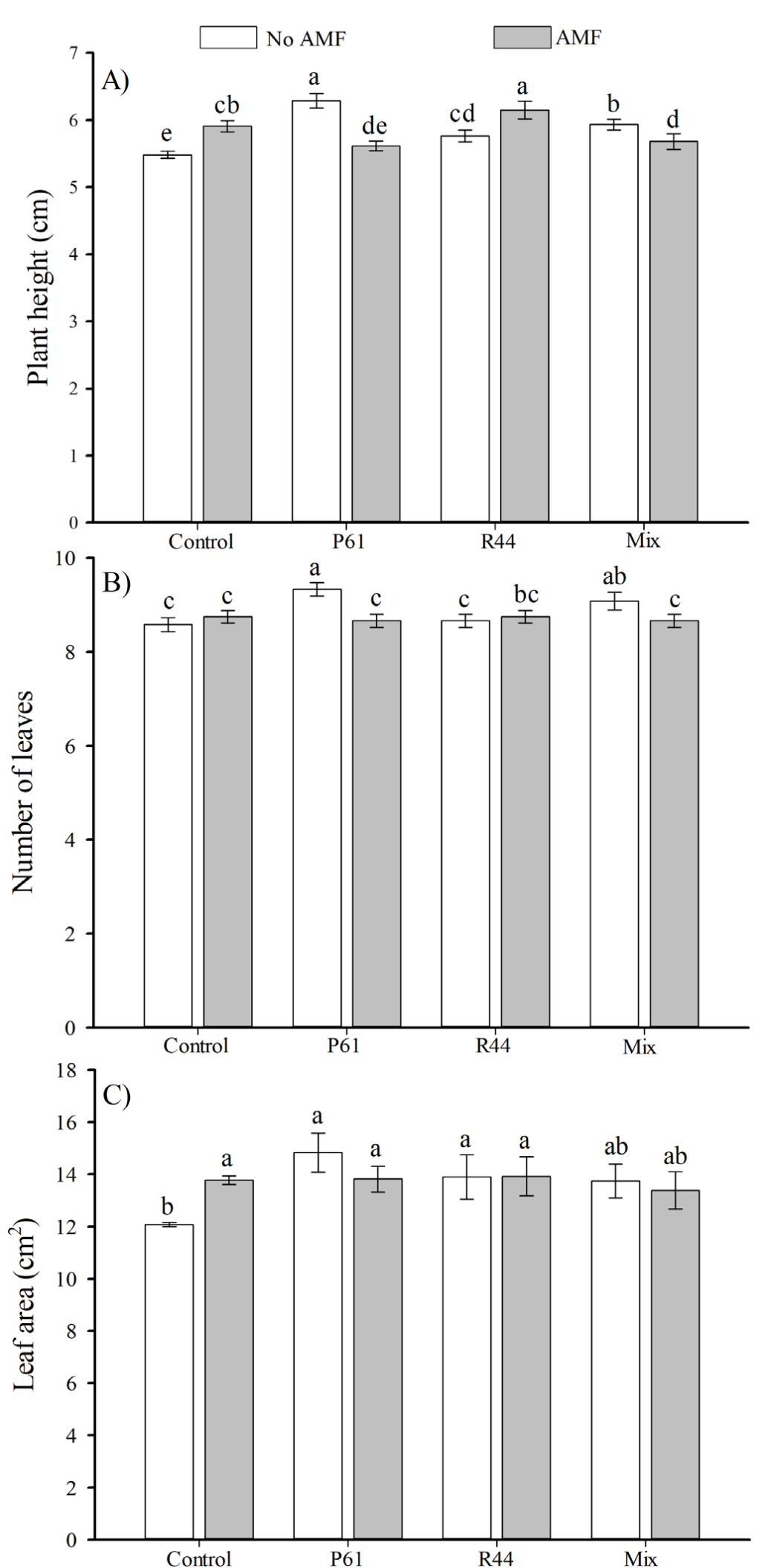

Plant growth parameters had significant responses due to the interaction of AMF and bacterial inoculation (Table 1, Figure 1). Thus, the results are presented and described in terms of such interactions as treatment effects. Overall, plant height, number of leaves and leaf area were significantly increased in plants inoculated with the bacterial strain P61 when compared to the uninoculated control (Figure 2A-C). In addition, the individual inoculation of AMF resulted in significant increased plant height (>7.8 %) and leaf area (>14.2 %) in comparison to control plants (Figure 2A and B).

Table 1 Significance of main significant effects of independent factors (AMF inoculation or bacterial inoculation) and their interactions on the evaluated parameters of bell pepper plants (Capsicum annuum), after 80 days

| Independent factors / Interaction | Plant height (cm) | Leaf number | Leaf area (cm2) | Dry weight (g) | Root volume (cm3) | Stem diameter (mm) | SPAD units | Chlorophyll fluorescence Fv/Fo | ||

| Total | Shoot | Root | ||||||||

| AMF | NS | 0.05 | NS | NS | 0.05 | NS | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Bacteria | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | NS | NS | NS | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| AMF × Bacteria | <.0001 | 0.005 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| C.V. (%) | 3.46 | 5.25 | 15.26 | 15.54 | 18.09 | 19.67 | 6.56 | 3.47 | 0.00 | 12.93 |

AMF: Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. NS: No significant differences. C.V. (%): Coefficient of variation.

Figure 1 Visual aspect of experimental treatments after 80 days of transplanting. Control: Uninoculated plants. P61: Plants inoculated with the bacterial strain P61 Pseudomonas tolaasii. R44. Plants inoculated with the bacterial strain R44 Bacillus pumilus. Bacterial Mix: Plants inoculated with the bacterial strains P61 and R44. AMF: Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal consortium integrated by Funneliformis aff. geosporum and Claroideoglomus sp.

Figure 2 Height (A), number of leaves (B), and leaf area (C) of bell pepper plants (Capsicum annuum) in response to inoculation with plant growth promoting bacteria and the consortium of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), after 80 days. n=12. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments (LSD, α=0.05). Means ± standard errors. P61: Pseudomonas tolaasii. R44: Bacillus pumilus. Mix: P61 + R44 bacterial strains.

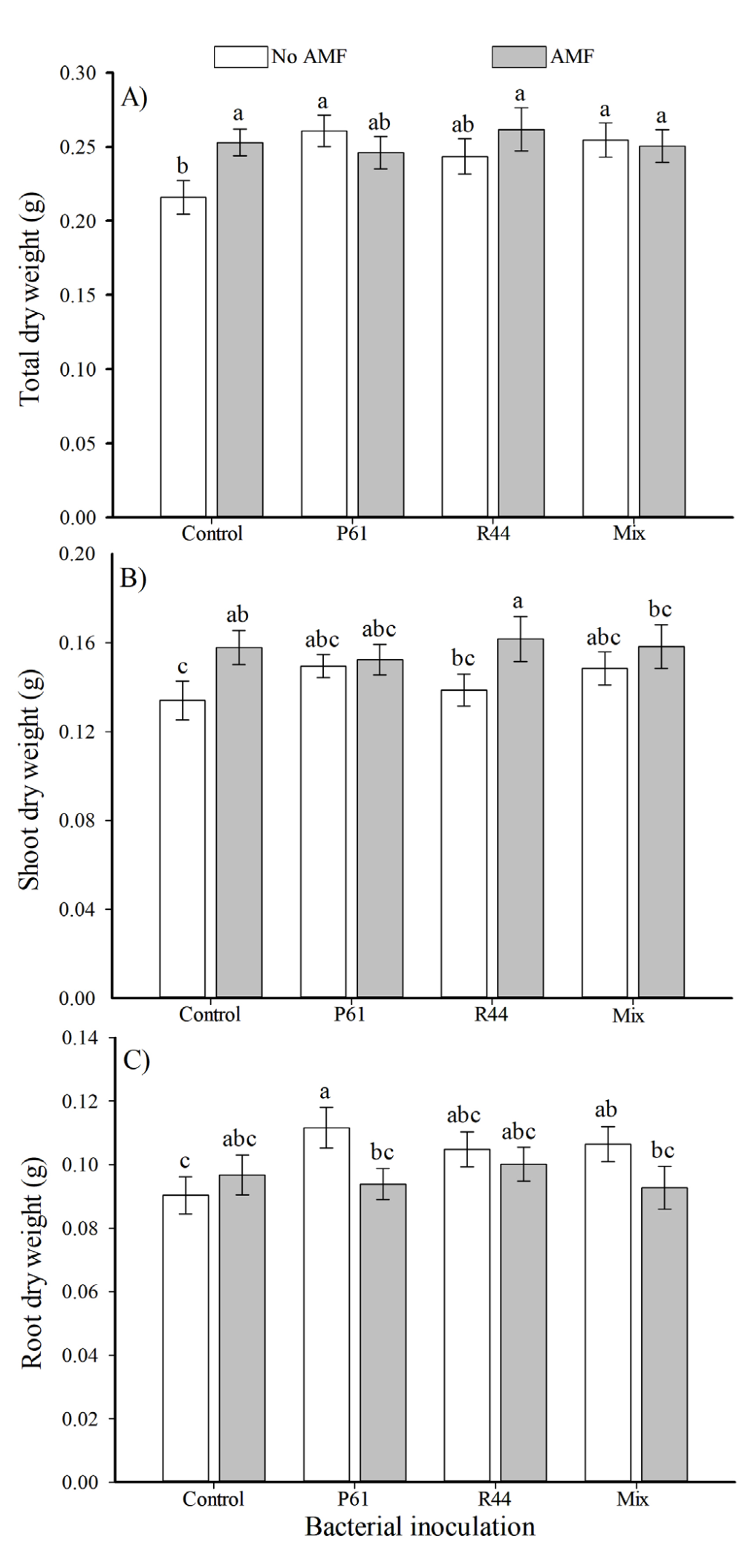

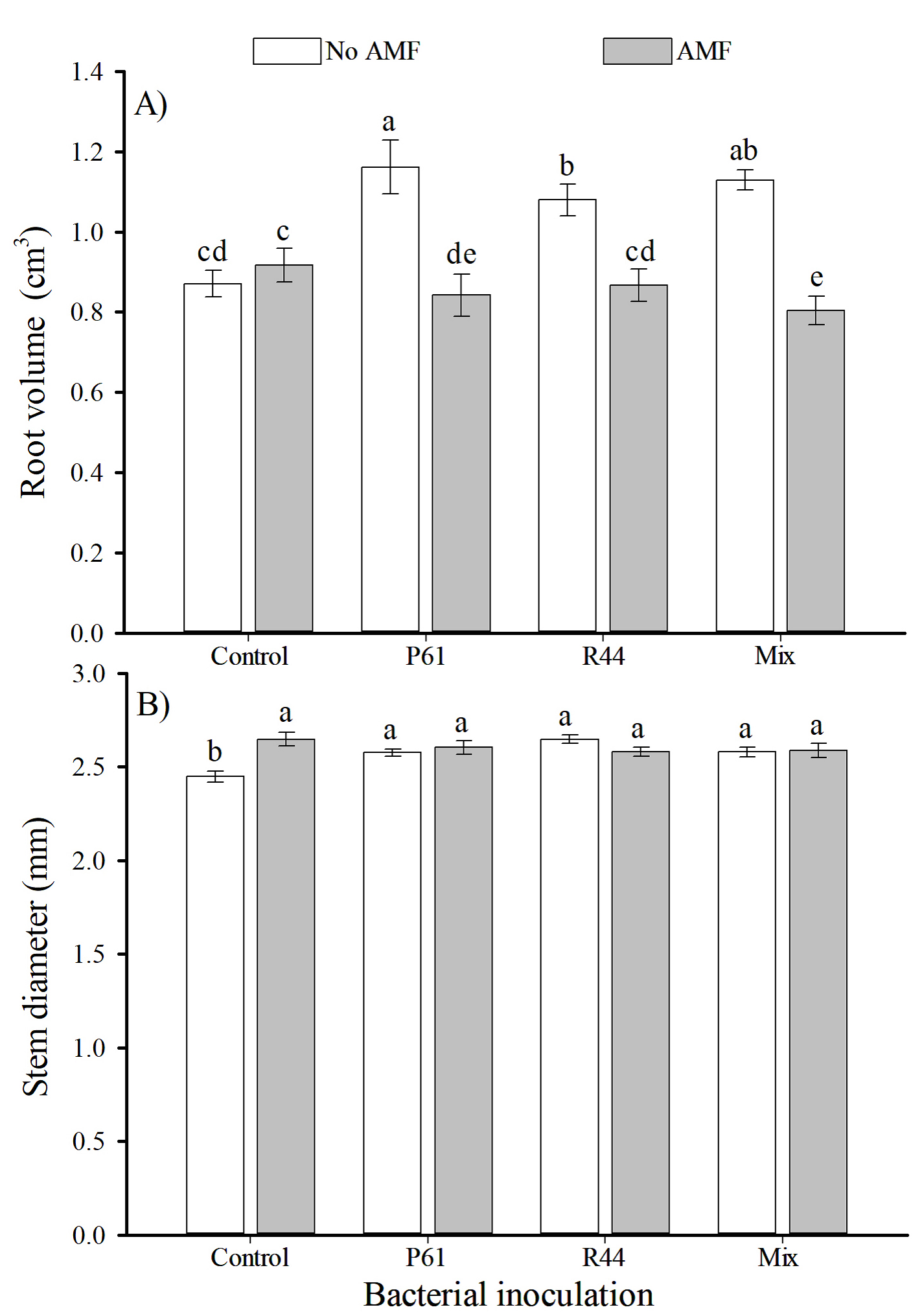

Control plants showed significantly lower total dry weight than plants only inoculated with AMF, which showed an increase of 19 % in the total dry weight (Figure 3A). Plants inoculated with R44 + AMF showed significantly higher (>23 %) shoot dry weight than uninoculated control plants (Figure 3B). However, plants solely inoculated with P61 had a significantly greater root dry weight (>23 %) than uninoculated control plants (Figure 3C). Plants from treatments P61, R44, and the bacterial mix showed significantly higher root volume (>33 %, >24 %, and >29 %, respectively) than control plants, and remaining treatments (Figure 4A). Furthermore, either bacterial strains alone or combined with AMF inoculation resulted in significantly greater stem diameter (>6.5 % in average) than uninoculated control plants (Figure 4B).

Figure 3 Total dry weight (A), shoot dry weight (B), and root dry weight (C) of bell pepper plants (Capsicum annuum) in response to inoculation with plant growth promoting bacteria and the consortium of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), after 80 days. n = 12. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments (LSD, α = 0.05). Means ± standard errors. P61: Pseudomonas tolaasii. R44: Bacillus pumilus. Mix: P61 + R44.

Figure 4 Root volume (A) and stem diameter (B) of bell pepper plants (Capsicum annuum) in response to inoculation with plant growth promoting bacteria and the consortium of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), after 80 days. n = 12. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments (LSD, α = 0.05). Means ± standard errors. P61: Pseudomonas tolaasii. R44: Bacillus pumilus. Mix: P61 + R44.

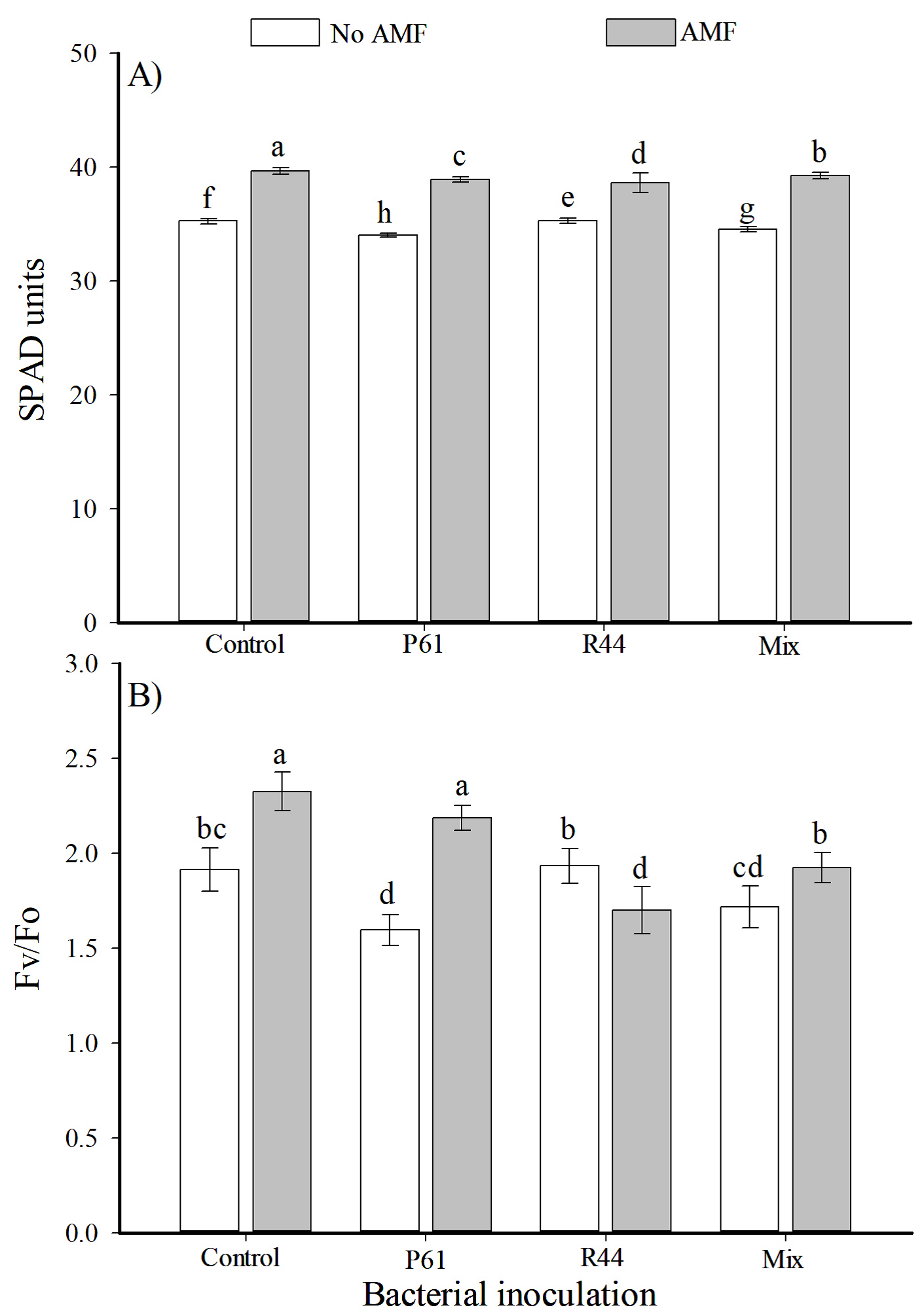

Both control plants and plants solely inoculated with the bacterial strains resulted in significantly lower SPAD units when compared to AMF plants regardless of bacterial inoculation; thus, plants from all AMF treatments had increased values of SPAD units (12.5 % more) than the remaining treatments (Figure 5A). The Fv/Fo values were significantly greater in plants solely inoculated with AMF (> 21.5 %) when compared to uninoculated control plants; in the same manner, plants from treatment AMF + P61 had significantly higher Fv/Fo values (> 37 %) than plants solely inoculated with P61 strain (Figure 5B). The TMC showed significant differences (P≤0.05). Plants solely inoculated with AMF (11.3 %) as well as plants inoculated with R44 + AMF (11.8 %) or inoculated with bacterial mix+AMF (10.5 %) had statistically higher total mycorrhizal colonization than plants inoculated with P61+AMF (7.7 %).

Figure 5 SPAD units (A) and chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fo) (B) of chili plant (Capsicum annuum) bell pepper in response to inoculation with plant growth promoting bacteria and the consortium of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), after 80 days. n = 12. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments (LSD, α = 0.05). Means±standard errors. P61: Pseudomonas tolaasii R44: Bacillus pumilus. Mix: P61 + R44.

Discussion

The interaction between PGPR and AMF (R44 + AMF treatment) showed the greatest responses in terms of plant height and shoot dry weight of bell pepper plants; however, the single inoculation of the bacterial strain P61 (P. tolaasii) showed greater effects on the plant growth parameters than the remaining treatments, especially when compared to the uninoculated control. Therefore, it is possible to consider the beneficial effects of bacterial strains on plant growth promotion as documented for other experimental approaches (Viruel et al., 2014; Angulo-Castro et al., 2018). Likewise, the AMF consortium inoculated in the present experiment (Funneliformis aff. geosporum and Claroideo-glomus spp.) induced effective benefits on bell pepper plants, which agrees with beneficial effects achieved by AMF inoculation on plant growth of several horticultural crops (Alarcón et al., 2012) as well as on poblano pepper plants (Carballar-Hernández et al., 2018).

The plant height, number of leaves, leaf area, and total dry weight showed positive responses to microbial inoculation, especially when plants were inoculated with strain P61 or with the combination of R44 + AMF in comparison to uninoculated control plants. The positive effects of the dual inoculation of PGPR and AMF might be due to the combination of certain physiological mechanisms of both microorganisms that promote plant growth like producing indole compounds or favoring the nutrient uptake (Tanwar et al., 2014; Boostani et al., 2014; Glick, 2012). In this regard, Neeraj (2011) observed significant increases on plant height and dry matter of bean plants inoculated with AMF (Glomus sinuosum, Gigaspora albida) in combination with Pseudomonas fluorescens, thus confirming the beneficial interaction between AMF with PGPR. In contrast, some studies indicated that the dual inoculation results in decreased plant growth. For instance, Larsen et al. (2009) observed decreased growth for Cucumis sativus inoculated with Glomus intraradices and Paenibacillus macerans. Thus, these negative effects might have accounted for the plants inoculated with P61 + AMF, so that this combination resulted in limited growth for bell pepper plants. These negative outputs may be in part explained by the compatibility between AMF and plant host, plant phenology, fungal genotype (genetic variability), AMF species with low effectiveness, and origin of fungal strain, compatibility or incompatibility with other microbial organisms, and carbon source-sink interactions between AMF and plants (Jin et al., 2017). Both root dry weight and root volume showed greater responses to the inoculation of bacteria P61 without AMF. This effect is explained in part because AMF hyphae have more effective soil exploration, and improve nutrient uptake and assimilation by plants, indicating that AMF mycelium acts as an extension of roots; thus, the plant does not require greater root growth and development. For example, Aguirre-Medina et al. (2002) found that AMF inoculation increased shoot biomass but reduced root dry weight in bean seedlings. Soti et al. (2015) observed a similar response in Lygodium microphyllum, in which a negative correlation between AMF and root growth was observed, but without affecting the aerial part. This finding indicates that root growth responses in mycotrophic plants are mediated by AMF. In contrast, PGPR may allow the synthesis of phytohormones by which the root architecture is modified, as demonstrated by Díaz-Vargas et al. (2001) in lettuce plants. Furthermore, stem diameter showed no significant increase due to the interaction between PGPR and AMF in comparison to their individual inoculation. Similar responses were reported by Kavatagi and Lakshman (2014) in AMF tomato plants inoculated with either Pseudomonas fluorescens or Azotobacter chrococcum.

Measurements of SPAD units provide a simple, fast, and nondestructive method to estimate the chlorophy II content in leaves (Uddling et al., 2007). The benefit of AMF on this parameter is attributed to the capability of AMF mycelium to improve nutrient uptake, after which the content of chlorophyll is enhanced (Koide and Kabir, 2000), although the nutrient content of leaves was not considered in the present study. Camen et al. (2010) observed a positive relationship between the chlorophyll content and mycorrhizal colonization in lettuce plants. Likewise, Kumar et al. (2012) indicated that the bacterial strains P10 and P13 (Pseudomonas fluorescens) combined with AMF improved the chlorophyll content in sorghum plants. In contrast, the low SPAD readings achieved in plants inoculated with PGPR is attributed to the observation that our bacterial strains used in this experiment did not possess the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, but produced indole compounds and solubilized inorganic P sources by which may exert beneficial effects on plants (Glick, 2012; González-Mancilla et al., 2017). Rodríguez-Mendoza et al. (2013) observed a similar response in cantaloupe plants inoculated with PGPR, which had a greater plant height and leaf dry weight than control plants, but no significant effects were observed in chlorophyll content (SPAD units).

The photochemical efficiency of photosystem II can be measured by an effective and noninvasive technique to detect damages in the photosynthetic apparatus of plants throughout the estimation of chlorophyll fluorescence. Thus, the Fv/Fo ratio (ratio between variable fluorescence and initial fluorescence) indicates the potential of the photosynthetic capability of PSII (Zhang et al., 2014). This parameter indicates the impairment in the photosynthetic chain of electron transport, and the decrease in this ratio denotes deteriorations in the electron transport (Pereira et al., 2000). This technique has already used to measure stress in pepper plants, providing very satisfactory estimates (Bhandari et al., 2018). The AMF may stimulate photosynthetic activity in plants due to an improved nutritional status under stressful conditions (Zhao et al., 2015; Elhindi et al., 2017). The lowest Fv/Fo readings obtained in plants inoculated with P61 or with R44 + AMF were opposite to those observed beneficial effects on the growth of bell pepper plants. The low values of Fv/Fo readings might be due to nutritional stress of plants at the end of the experiment, as discussed by Zhang et al. (2014), but also to negative effects of microbial interactions in plants (Tsukamoto et al., 2002). Therefore, the bacterial mix might have exerted inhibitory effects on each other, thus affecting plant growth by competing for C-sources from plants or altering the balance of phyto-hormones that may result in inhibitory effects on plant growth, as discussed by Glick (2012). However, this effect needs further research for elucidating potential negative effects on plant growth under specific environmental/agronomical conditions.

Overall, under our experimental conditions, the TMC ranged from 7.7 to 11.8 % in the four treatments in which AMF were inoculated. In addition, no mycorrhizal colonization was detected for plants without AMF inoculation. In general, TMC was low in all AMF treatments when compared to other scientific reports in which it ranged from eight to 46 % (Marschner et al., 1997; Kaya et al., 2009); however, the plant responses to AMF inoculation was favorable, except for root volume and root dry weight. Even though the total mycorrhizal colonization percentage was low in all treatments inoculated with AMF, no growth limitations were detected in these plants. This result indicates that the degree of mycorrhizal colonization is not always a clear indicator of the potential benefit for plants (Alarcón and Ferrera-Cerrato, 1999). In contrast, plants with P61 + AMF showed lower mycorrhizal colonization (7.7 %) than the remaining AM-inoculated plants. The latter is an indication of possible antagonistic interactions between P. tolaasii and AMF, and this bacterial antagonism has been described for fungal species, particularly pathogenic fungi (Haas and Defago, 2005). However, there are no reports regarding the antagonism between P. tolaasii and AMF (Funneliformis aff. geosporum and Claroideoglomus sp.). Furthermore, the toxin tolaasin produced by P. tolaasii seems to have antifungal properties (Rainey et al., 1993).

This research demonstrates that beneficial microorganisms such as PGPR and AMF may have significant effects on the growth of horticultural species such as pepper plants. Nevertheless, it is necessary to understand and evaluate potential benefits achieved between both microbial groups, since certain combinations of PGPR with AMF did not exert significant benefits on plant growth. Nevertheless, these microorganisms represent a biotechnological potential for stimulating the growth of bell pepper plants to assure early benefits and to improve better plant adaptation to field conditions (Diniz et al., 2009; Anith et al., 2015).

Conclusions

The single inoculation of the strain P61 or the AMF consortium, and the dual inoculation of R44 + AMF significantly improved plant height, leaf area, dry weight (shoot, root and total), and root volume. Moreover, the single inoculation of P61, R44 and the bacterial mix resulted in enhanced root volume. Conversely, the AMF consortium exerted beneficial effects on the measured physiological parameters (SPAD units and Fv/Fo readings) either individually inoculated or in combination with the P61 strain. Results denote that either the two bacterial strains or the fungal mycorrhizal consortium stimulated the growth of bell pepper plants by applying the microbial inoculum at seed starting containers stage. Thus, the inoculation of beneficial microorganisms may be an important agronomical practice for producing horticultural plants with improved growth and vigor at early growth stages.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)