Introduction

International studies show that overweight and obesity are two of the medical conditions with the highest burden of disease1 and their risk of mortality increases when comorbidity with diabetes and hypertension is met.2-6 Current evidence shows that overweight and obesity have significant effects on several areas, diminishing quality of life and overall health.7-9

Obesity has not only shown high comorbidity with general medical conditions, but also with specific psychiatric comorbidities,10-12 such as depressive and anxiety disorders, substance abuse, and suicidality.12-18 This results in 1.18 times more probability of showing depression when compared to non-obese individuals, regardless of cultural background.19 Regarding suicide, studies have found that women with obesity have greater frequency of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, compared to men with obesity.20

Few studies have associated body mass index (BMI) with substance use. Evidence indicates that overweight and obesity are related with a higher risk of alcohol use disorder in men, but not in women21 and that obesity and tobacco use significantly increases the risk of mortality.22,23 Furthermore, substance use in obese individuals increases 34%-89% after bariatric surgery.24

The study of psychiatric disorders in individuals with obesity is particularly relevant because these conditions are associated with low adherence to treatment, higher utilization of health services, and negative results in health examinations.25,26 Gender, age, socioeconomic status, and obesity class act as potential moderators in the relation between obesity and depression16,27,28 whereas gender differences are consistent with substance use and suicide.20,21 However, evidence is still controversial because of the possibility of interactions between sociodemographic variables and obesity.

It is relevant to state that Mexico is one of the countries with the highest rates of overweight and obesity.1 According to the Mexican Health and Nutrition Survey (ENSANUT, 2012), the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and overweight (BMI between 25 and 29.9) in the Mexican population between the ages of 20-69 is 32.4% and 38.8% respectively, with 73% of women and 69.4% of men showing either of these conditions.29 Notwithstanding the impact of obesity in Mexico, few studies have evaluated the relation between mental disorders and substance use, and those that are available are derived from small samples30 and with specific populations, e.g. students.31

Considering that in Mexico the relation between obesity and mental disorders has not been sufficiently studied, the present work has the following objectives: a) to evaluate the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms; b) to evaluate the interactions between obesity classes and demographic variables in relation to psychiatric symptoms; and c) to analyze the interactions between obesity class, demographic variables, and psychiatric symptoms in association with medical comorbidities in a sample of individuals that seek treatment for obesity.

Method

Design

This analysis was developed following the methodology of Medical Record Review (MRR),32 which refers to any study that uses pre-recorded patient-focused data as the primary source of information to answer a research question.

The medical records were registered in the first contact with physicians at 22 outpatient community centers specialized in obesity and weight loss treatment in four states of Mexico (18 in Mexico City, one in Puebla, one in Morelos, and two in the State of Mexico). The centers comply with current Mexican regulations for outpatient primary care (NOM-178-SSA1-1998). Data was collected between January 2014 and December 2014.

Study sample

The medical records included in this analysis belong to patients who seek weight reduction treatment at outpatient community centers and endorsed obesity criteria established by the international standards from the World Health Organization (Class I: BMI of 30 to 34.9 kg/m2, Class II: BMI of 35 to 39.9 kg/m2; Class III or severe obesity: BMI greater than 40 kg/m2).33 Records from patients younger than 18 years old were excluded from the analysis (figure 1).

Measurements

The medical assessment was integrated by: a) standardised clinical interview, b) point of care glucose testing, c) blood pressure (diastolic and systolic in mm/Hg), and d) anthropometric measurements including: waist circumference (in centimeters), height (in centimeters), weight (in kilograms) and BMI (in kg/cm2). Diabetes II, hypertension and dyslipidemia cases were taken as stated in the patient's medical record.

To assess psychiatric symptoms and substance use, the standardised clinical interview used the following questions: depression symptoms "In the past 30 days have you felt significantly sad or depressed"; anxiety symptoms "In the past 30 days have you felt significantly anxious or nervous?"; suicide attempt "In the past year have you made any suicide attempts?"; daily smoking "In the past year have you been smoking at least one cigarette per day?"; alcohol use "In the past year have you been drinking at least once per week?"; drug use "in the past year have you used any drug at least once?".

Procedures

The database was conformed from a community prevention and treatment program for obesity and weight loss sponsored by public institutions in 22 sites across Mexico City, the State of Mexico, Morelos, and Puebla. This community treatment program aimed to provide free medical care to individuals seeking treatment for weight loss. As a part of the procedures the physicians performed medical assessments and requested consent to use the patients' data for research. All physicians who participated in the medical assessment were certified in obesity and weight loss treatment.

Ethical considerations

Patients signed a written informed consent approving the use of their data for research purposes. A technical and ethical academic committee approved all procedures for this data analysis and to preserve confidentiality, the identification and localisation data of the patients wee de-identified in compliance with Mexican research regulations (NOM-012-SSA3-2012), and international standards of good clinical practices for human research.

Statistical analysis

Demographic, medical and psychiatric variables were summarised using mean and standard deviation for numeric, frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Univariate differences between three obesity classes were tested using one way ANOVA for numerical and chi square (χ2) for categorical variables. A second step to test associations between obesity, demographics, medical and psychiatric variables was to perform univariate binomial logistic, then two-way interactions between obesity classes and demographic variables were tested for psychiatric variables, and two-way interactions between obesity classes, psychiatric and demographic variables were tested for medical variables. When two or more two-way interactions were significant, three-way interactions between the variables were tested. Statistical analyses were performed using R software v 3.2.3. Significance was set to p < .05.

Results

A total sample of 13,305 patients (records) met eligibility criteria, with a mean age of 42 (SD = 12) years old, and most of them were women, married, and with elementary or high school education. Mean BMI (SD) for obesity classes I, II and III were: 32.19 (1.41), 37.00 (1.40), and 43.97 (3.83) respectively; while in the whole sample mean BMI was 34.94 (SD = 4.39). Between groups (obesity class) significant differences were found in age, marital status, education, waist circumference, diastolic and systolic blood pressure, and glucose level (table 1).

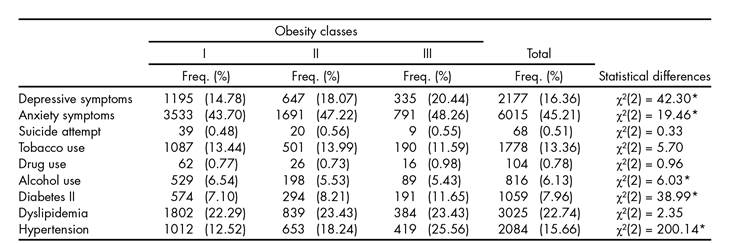

Regarding the prevalence of psychiatric and other medical conditions, the most prevalent were: anxiety and depressive symptoms, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Significant differences were found between groups for anxiety and depressive symptoms, alcohol use, diabetes, and hypertension (table 2).

When univariate predictors were added, most of the demographic and obesity classes were significant, excluding the association between obesity class III and alcohol use. The only significant second order interactions for anxiety symptoms were obesity class III by gender and obesity class II by age, while for alcohol use obesity class II by gender interaction was significant (table 3).

Table 3. Regression models for psychiatric symptoms (n = 13305)

a Obesity class I was the comparison

b Comparing men to women

c Not estimated

*p <.05.

In the logistic regression analysis for medical comorbidities, obesity class, demographic variables, and psychiatric comorbidities were significant. The only significant second order interaction was obesity class III by being married for diabetes (table 4).

Discussion and conclusion

The present study aimed to assess the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and the interactions between obesity and demographic variables, and to determine its association with medical comorbidities in a sample of patients with obesity seeking treatment for weight loss.

It was found in univariate analysis that the probability of anxiety and depression symptoms increase as the obesity class increased; however, that relation was found to have an opposite direction with alcohol use. When analyzing second order interactions between demographics and obesity class it was found that men with class III obesity had more probability for anxiety symptoms when compared to men with obesity class I and II; for women with obesity class I, there is a direct relationship between the age and the probability of anxiety symptoms, when compared to women with obesity class II and III. These results are consistent with previous studies,10,13,21,27 suggesting that the increase in BMI is associated with the probability of depression and anxiety symptoms, (13 suggesting that such relationships are moderated by the interaction of gender and age, implying that the effect of obesity in mental health varies across gender and age groups.

Men with obesity class I displayed higher odds for alcohol use when compared with obesity class II and III. This finding might support the hypothesis that compulsive eating and substance use compete for the same circuits in the reward system, hence, as one behaviour increases the other is less likely to occur.34,35 The main common factor between eating and substance use is dopamine release in the mesolimbic pathway, as the eating habits and the rewarding properties of food lead to neuroadaptation of the reward, motivation, and decision-making circuits, resulting in a subsequent loss of control and compulsive behaviours. However the opioid, GABAergic, or cannabinoid systems are implicated too.35,36,37,38 Previous evidence strongly suggests that substance use and food compete in the reward system; taking into account that food consumption is much more complex, it is plausible that the brain adaptation to overeating is harder compared to substance use.35

The characteristics of the sample are another relevant finding, as most were women with an age around 42 years old, with elementary education and married. When we consider global (men 37% and women 38%) and Mexican (men 26.5% and women 37.5%) obesity rates,2 it is clear that there is an important difference in the rates by gender of individuals seeking treatment for obesity when compared to the national and global men to women ratio. This may point to the existence of gender-specific barriers limiting the attendance of men, such as attitudes and beliefs towards health care (underestimating risks, resistance to pain, perception of invulnerability), work hours and socioeconomic status;39,40 the age, education, and marital status of the sample. This implies that there are particular profiles of patients using this service, therefore it is necessary to develop tailored interventions based on these variables; for instance, as the majority of the patients were married and had an elementary education, a weight reduction program focused on partner and family social support might boost the effects of the intervention.41,42 In terms of educational level,43,44,45 is important that the provision of information is paired with the patient's education, otherwise it might be difficult to initiate behavioural changes. This result highlights the importance of tailoring specific weight loss programs, and to develop strategies to increase men's attendance to treatment.

Future studies should focus on the complex relations between obesity and psychiatric symptoms, particularly because weight loss treatment requires dietary and behavioural changes, and such lifestyle modifications are significantly affected by psychiatric variables; this becomes clear as we see the findings of previous studies that point out that anxiety and depression symptoms increase the likelihood of sedentary lifestyles, eating unhealthy food, and binge eating.15,27

This study had the following limitations: the cross-sectional design made it impossible to determine the temporal sequence of the events, and we were unable to identify which psychiatric symptoms preceded obesity. A second limitation is that the measurement of psychiatric symptoms used a single question instead of using a structured interview or a validated scale, thereby limiting the internal validity of the results, and implying that future studies will require the use of these measurements. A third limitation is that the method to diagnose hypertension, diabetes II and dyslipidemia is unclear for every patient, resulting in a probable underestimation of their prevalence.

Finally, this is one of the few studies in Mexico using a considerable clinical sample allowing testing of complex interactions between variables. This study also points out important patient characteristics that enable us to understand particular requirements needed for tailoring treatment. These results highlight that the complexity of the relationship between demographics, obesity, and psychiatric symptoms might be decisive for the outcomes in weight loss treatment;46,47 however, it seems necessary to conduct more studies using longitudinal designs and assessing other relevant psychiatric disorders, such as attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder.48 In conclusion, weight loss treatment programs must take into account the interaction between psychiatric symptoms, gender, and educational level, to boost treatment adherence25,26 and weight reduction, finally having an impact on the treatment costs and the patient's quality of life.49

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)