1. Introduction

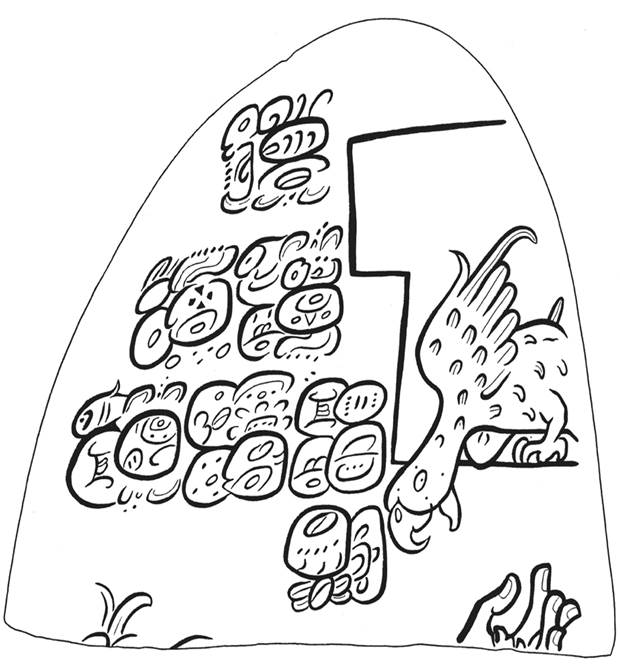

Despite its diminutive size, the incised shell known as K8885 is a gem of Maya scribal art (Figure 1). The inscribed text is distinguished for its use of first-and second-person pronouns, referring to a parrot and a scribe, with the artist himself interacting in an intimate scene from which we are missing a significant portion. The parrot is perching within a T-shaped window, the scene apparently taking place in a room within a building. Part of the headdress of the scribe is visible, as is one of his hands reaching up to the parrot, perhaps to feed her. The unusual text immediately generated considerable interest and discussion among epigraphers (Kerr, 2009).

In this article we argue that it also presents a unique opportunity to constrain the semantics of the rare T650 glyph, providing valuable clues towards its phonetic reading.1 The text in the shell can be analyzed as follows:

‘a-hu-le-li-ya ti ni-T650-la me-te ya-‘a-la-ni ‘o-po ya-‘a-[la]-ji-ya hu-bi

‘u-ju-chi [2]po-lo tz’i-‘i ba-che-bu

‘ahuleliiy ti ni- ? met ya’alan ‘op ya’alajiiy huub

‘ujuhch Popol Tz’i baah cheeb

‘(it is) your arrival/you arrive at my ? nest,’

he says (tells) it, the parrot, said (had told) the shell;

it is the conch shell of Popol Tz’i,’ first of the brush (scribe)’

The first sentence, spoken by the parrot (Polyukhovych, 2007; Zender, 2017), ends with the word met, which is glossed specifically as ‘nest’ in Ch’ol (Aulie and Aulie, 1978) and whose cognates in other Mayan languages point to a more general meaning of ‘any object bent or twisted into a circle’ (Zender, 2017). It is reasonable to think that the preceding collocation is adjectival, specifying some aspect of the nest. This interpretation is reinforced by the presence of a -la suffix on T650.2

As seen in K8885, T650 has a CHUM-like contour, with a very visible body part marker and in the center, four radial “dark cake slices”. The glyph, or simply the “dark cake slices” iconographic element, is relatively rare in the corpus, and besides K8885 itself appears in only a few but important contexts: a sculptured wall and Monuments 8 and 156, at Tonina; a theonym of Kokaaj Bahlam, king of Yaxchilan, and in the plate K9072; the name of two Kaanul kings from Dzibanche’, including “Sky Witness”; a theonym of K’ihnich Waaw, king of Tikal; a narrative in Panels 5 to 8 at Xcalumkin; a stucco text at Palenque; the shells of certain turtles, and; a paired tree/stone-setting in “The Regal Rabbit Vase” (K1398). Below we present our proposal for the reading of T650. We will begin with a presentation of the phonetic evidence which supports this proposal, followed thereafter by a discussion of how this reading explains all contexts (lexical and non-lexical) where the sign appears.

2. Phonetic Evidence

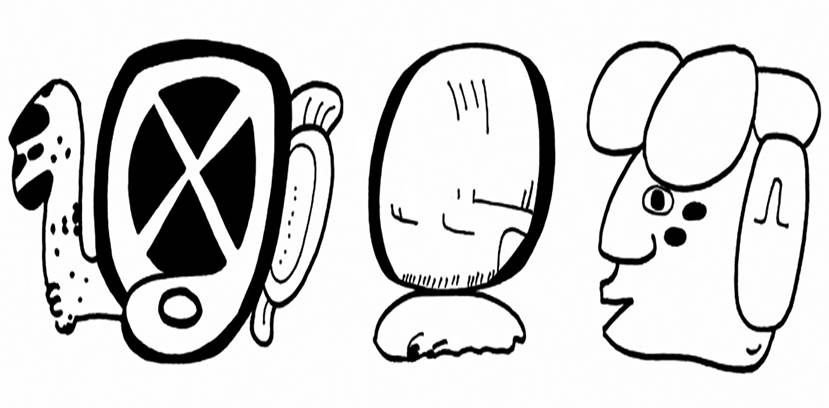

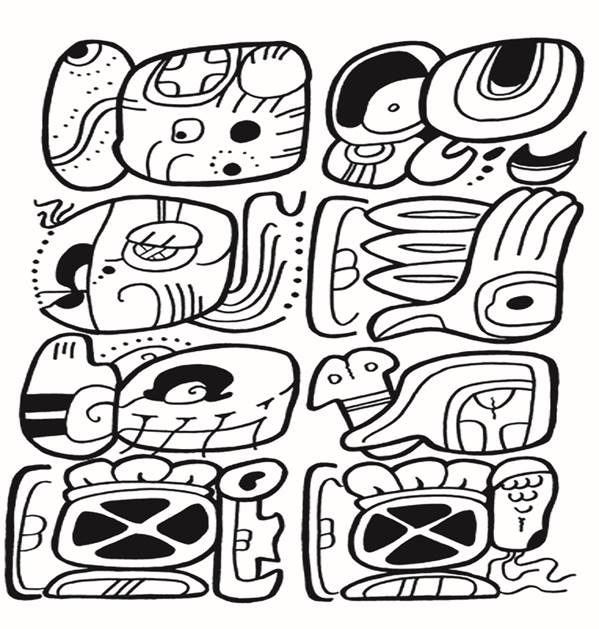

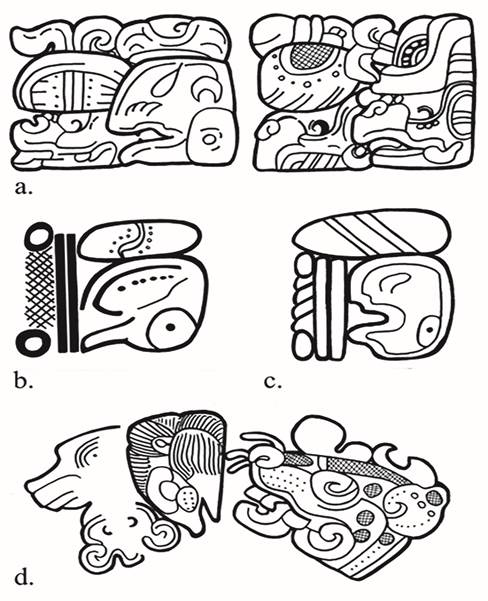

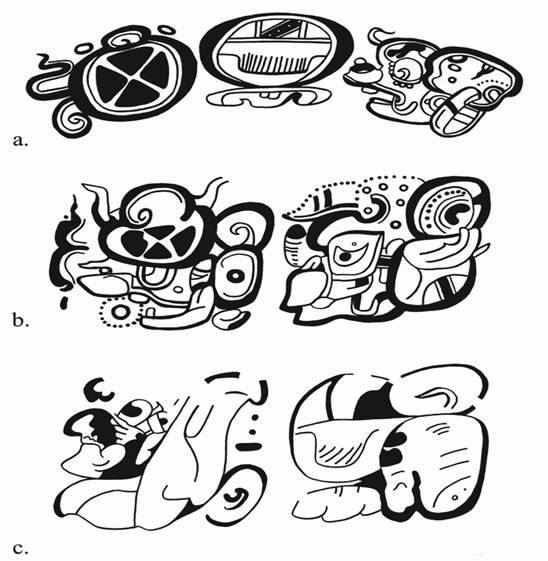

The contexts in which T650 appears, namely in theonyms and royal names, suggest a non-syllabic value for the sign, as does to a lesser degree its rarity in the script. The Yaxchilan examples (Figure 2) are all confined to a rather opaque theonym, part of the long string of epithets carried by Kokaaj Bahlam “The Great”. The theonym involves the so-called “Bloody-Mouthed God” (henceforth “BMG”):

‘ICH’AK-“HAND”[T650]-si CHAN “BMG”

Figure 2 (a) Dos Caobas stela 1, after drawing by David Stuart, (b) K4614E, after drawing in Schele (n.d.), (c) Yaxchilan stela 18, after drawing by Ian Graham in Tate (1991) and (d,e) lintel 23 and HS3 step V, after drawings in Graham (1982).

Most of the examples of this theonym (Yaxchilan Lintel 23, Stela 18, Dos Caobas Stela 1 and Site R Panel K4614E; Figures 2d, c, a and b, respectively) have T650 conflated with a “HAND” syllabogram; this could be either cha, k’a, or ho because the diagnostic element in the hand is hidden by T650. Moreover, the text in HS3 step V shows that theonyms were shared among generations. Kokaaj Bahlam and his son, Yaxuun Bahlam, share theonyms with their father and grandfather, Aj Wak Tuun Yaxuun Bahlam, respectively:

TE’-ku-yu ?SIP CHAN-“BMG”3

and

‘ICH’AK-“HAND”[T650]-si CHAN “BMG”

We also note that in HS3 step V, the “HAND” sign is not conflated with T650 and thus appears to be optional (Figure 2e). The “HAND”[T650] examples (occurring exclusively at Yaxchilan) are unusual in that preposed phonetic complements are rare and usually served to disambiguate readings (Grube 2010). Despite this writing convention for T650 (the example in HS3 Step V seemingly an exception), the “HAND” in these collocations can hardly be understood as a phonetic complement, as the scribes covered the diagnostic part of the sign which would have allowed the reader to distinguish between a cha, a k’a or a ho. This is presumed to encode an archaic convention for the theonym or be a case of scribal play.

In this context, it is noteworthy that plate K9072 carries a structurally similar theonym (Figure 3) with the CHUM-like contour of T650, but as with the HS3 Step V example, it lacks the “HAND”:

‘ICH’AK-T650-si CHAN “God”

This CHUM-like contour is also seen in some of the conflated examples at Yaxchilan (Figures 2b, d). The final -si is consistently present at Yaxchilan and appears in K9072 as well; it is very likely marking the absolutive or non-possessed (body part) noun suffix -is. While many glyphs carry body markers without cueing body parts (e.g., the syllabograms chi, ke, k’o, ye, yo and the logograms ‘AHN, CHOK, CHUM, HUL, TZUTZ, ‘UK’, and WE’) the assumption that the final -si marks the absolutive also conforms with other theonyms at Yaxchilan, namely T533-si CHAN-“BMG” (a title of Chelew Chan K’ihnich) and K’AK’-?-wa-si CHAN-“BMG” (a title of Jatz’oom Jol).

In May 2021, Alexandre Tokovinine shared a fully phonetic substitution for T650 in the same theonym from a portion of Stela 23 at Yaxchilan (Alexandre Tokovinine, personal communication May 2021; Fash et al., 2022).4 In this context, Kokaaj Bahlam’s name is preceded by the theonym wherein T650 is replaced by T672:? (Figure 4). After much discussion of the alternatives for the partially eroded suffix, we have satisfactorily determined this sign to be T74 ma:

‘ICH’AK-T672:74 CHAN-na “BMG”-na

Figure 4 Detail of the text on the back of Yaxchilan Stela 23. Photo by Carlos Pallán Gayol (2007), courtesy of Ajimaya/INAH, National Archaeology Coordination, Mexico. Drawing of theonym passage after photo.

We argue that this is a bona fide substitution. First, jo-ma occurs in the exact same syntactic position as the “HAND”[T650] in the other examples of the theonym at Yaxchilan. Second, the “HAND” is unambiguously shown in this example to be a ho/jo hand sign. Finally, the -si is absent due to a lack of graphic space. Its absence does not alter the meaning, as the primary function of -si in this theonym is to mark the name that follows ‘ICH’AK as an unpossessed body part noun -- a formality given that the theonym must have been well-understood by the reader. Thus in what follows, we assume that the ho/jo-ma collocation is a full phonetic spelling of T650 signaling a reading of HOM or JOM.5

We now refer the reader to Appendix 1 for a complete inventory of jom entries in all relevant Mayan languages. These sources will be useful amid our discussions of each text example of T650.

The semantics of jom entries present a significantly wider range than that of the cognate set identified by Kaufman and Justeson (2003) for the reconstruction of proto-Mayan *johm, but this narrower inventory is the essential backbone for the recognition of cognacy in many entries in the languages most relevant to the script. We note, for example, in the reconstruction of *johm ‘gourd’ (of different types and uses) and ‘(dugout) canoe’ a fundamental attribute “hollow” resulting from human activity. This “hollow” concept leads directly to the many entries above related not only to gourds, canoes, and wooden basins, but also to Spanish incensarios, then to natural things and places: trunks of trees, the trunks and abdominal cavities of people and animals, hollow quills and thorns, eye-sockets in the skull, then to canyons and narrow valleys; then to holes: embrasures (narrow windows), troneras (portholes) and in the original *johm set: sinkholes, holes in the ground, cave-ins, and by extension, Yokot’an bogs. This, in turn, evokes an array of transitive verb entries having to do with making holes, opening (cutting) paths, piercing, biting, demolishing, and submerging, as well as intransitive verbs referring to the ‘ending’ of certain events and acts and the sinking and collapsing both of structures and in nature.6 A curiosity in the original *johm set is Q’eqchi’ ‘pelón’ (‘bald man’) which must relate to an underlying idea also seen in Yucatecan entries pertaining to clearing brush and removing vegetation.

However, we have identified another cross-linguistic set of homophonous jom entries related to (a) “heat” and “fire” in both the physical and metaphysical (as well as emotional) sense, and to (b) the rising/piling-up of natural or body/heart forces. We propose this set to include at the outset the Colonial-period *jVC entries ghomoltay, ghomoltez ‘amontonar/pile up’ as well as homel ‘diluvio’ (which we believe to be *jomel) in Colonial Tzeltal, and in Colonial Yucatec (all under “H rezia” [jVC] ), hom ‘cresciente de mar o rio’, homkaktah ‘quemar o pegar fuego’, homocnac ik ‘viento rezio y bravo que hace ruido/ strong, wild wind which makes noise’, and homol ol ti menyah ‘el apresurado, acelerado para trabajar/ one who is rushed/in a hurry to work’.

These now open a path to the inclusion of modern entries such as jomlij and jomomet in Tzotzil with meanings ‘running suddenly’ and ‘pushing oneself;’ Ch’ol participles jomol and jomtäl ‘amontonado(s)/piled up’; and Itzaj jom ‘large flame’ and jom k’ak’ ‘burn with flames of torch’. But of all these, the entries in this second set most applicable to the regnal names we will shortly analyze are the jom entries glossed specifically as ‘anger’ and ‘hot vapor’ or ‘heat’ in Ch’orti.’ Although employed for the fever of illness, this jom is also a metaphysical heat, an “inner heat” possessed by humans and gods that emanates from body parts such as the heart, hands, mouth, and eye in the form of ire/wrath in humans and lightning in the gods.

This view is supported by ethnographic fieldwork among the Ch’orti,’ wherein this metaphysical “heat” is viewed as a powerful and complex concept. The Ch’orti’ perceive it as an intrinsic property of bodies and spirits and assign it - in company with jom(ir) - names such as jolchan, hijillo and k’ahk’. One’s heat may protect him/ her from evil spirits and disease; however, it can also lie at the source of diseases, death, and “demonic possession.” The equilibrium is precarious and conditioned by many internal and external factors, the latter because it can be transmitted between persons and spirits through physical or visual contact and through moving air (Wisdom, 1940; Kerry Hull personal communication, June 2021).7

As we proceed through the script contexts for T650, we will recognize many of the above glosses from both the *johm ‘/(make) hole/hollow/open path’ set and the *jom ‘fire/metaphysical heat/wrath’ set. While these overlap in the milieux of rising seas and floods and of incensarios, we do not propose these sets to be cognate.

Finally, we suggest that the human-trunk-like or CHUM-like form of T650 may find an explanation in the entries homtanil (H rezia) ‘estomago, entrañas y lo hueco de qualquier animal’ (Arzápalo, 1995) and homtanil ‘hueco del pecho, la cavidad del pecho’ (Barrera Vásquez, 1980: 214), indicating this to be the “hollow” part of the body.

We now turn to the discussion of the script contexts for T650, starting with the lexical examples.

3. Lexical Examples

3.1 The K8885 Shell

In the scene, the parrot perches in a narrow T-shaped window in a palace room positioned above his owner’s head, thus invoking the Tzotzil entry ‘embrasure, tronera (porthole, small window)’ in Appendix 1.

For ti ni-jomal met we propose the translation ‘to/at my window-nest,’ wherein the noun jom, now with the suffix -al, functions as an adjective.

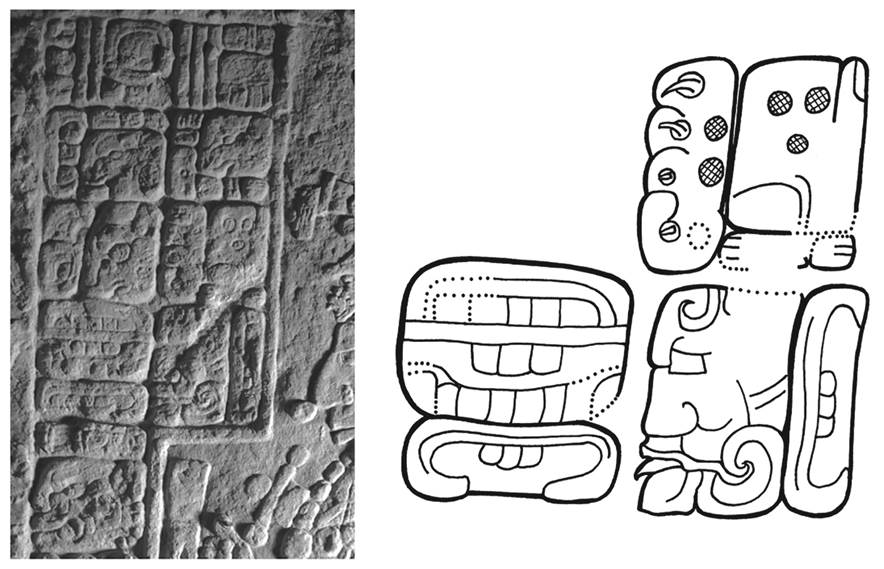

3.2 The Stucco Wall and Monuments 8 and 156 at Tonina

A new stucco wall was discovered in 2007 in the “Templo de las Luciérnagas” at Tonina. The text (Figure 5a) mentions the inauguration of a wall (u-kot) by a vassal of the Tonina king K’ihnich Baaknal Chahk (Polyukhovych, 2007). The text clearly states that it is the vassal’s wall, not the king’s, and refers to him through a sequence of titles: ‘AJ-K’UH-na, ‘AJ-?[JOM]-na and ‘AJ-CHAN-k’u-NAL. Clearly, only a high-ranking court official would have the privilege of owning a wall and be named thereupon.

Figure 5 (a) The Tonina wall (drawing by Yuriy Polyukhovych) and (b) Tonina, Monument 8, side 3 (detail), drawing by Peter Mathews. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.14.13, from Graham (1983).

The first expression is ‘aj k’uhuun, a high-ranking court office that included multiple functions (Jackson, 2001; Zender, 2004a; Wald, 2015; Sanchez et al., 2019: 47).8 The final expression is ‘aj chan k’u[h]nal (‘he of the four temples/gods-place’), perhaps a precinct in the city or a local toponym. Pertinent to our discussion is the middle expression, in which T650 is infixed into an elusive sign, noted by Polyukhovych to also follow T650 on Monument 156 (Figure 6) in association with the ‘aj k’uhuun title (Sanchez et al., 2019: 49), and is suffixed by the syllabogram -na.9

Figure 6 The collocation in Monument 156. Photo ©Jorge Pérez de Lara and Proyecto de Conservación y Documentación de Toniná de la CNCPC-INAH, drawing based on photo.

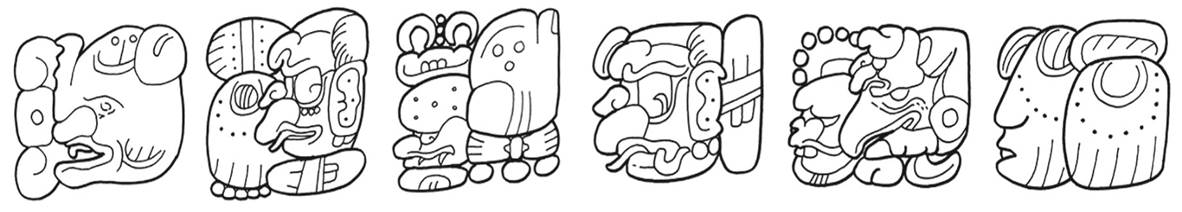

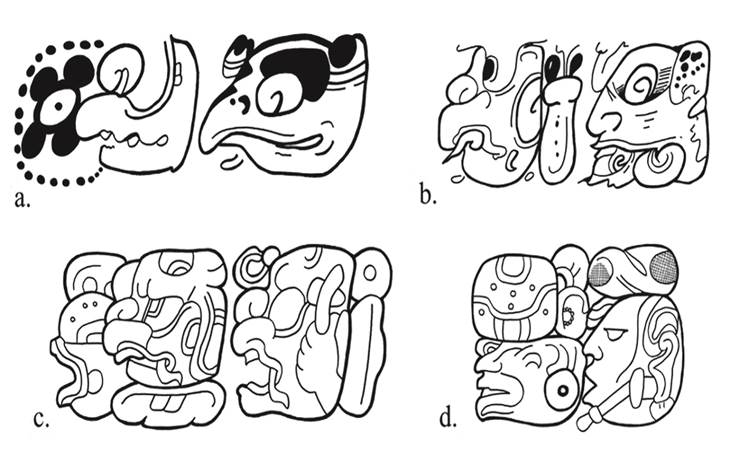

Using high-quality photographs of Monument 156, we identified the elusive sign as the “half-head” sign TI’ the full form of T128 (Figures 6 and 7a-c), which compares favorably to examples with the same “forehead curl” (Figure 8). This leads to a reading ‘AJ JOM TI’ ‘aj jom ti’ ‘he of the heat-mouth.’ The heat-related entries that clarify the semantics of this title can be found in Appendix 1.

Figure 7 (a) Copan Altar K, after drawing in Schele (n.d.), (b) K635, after photo in Kerr (n.d.), (c) Naranjo Stela 19, after drawing in Graham (1975) and (d) incised bone at Dallas Museum of Art, after drawing in Mayer (1989).

Figure 8 TI’ with a forehead curl: (a) K1387, after drawing in Martin and Reents-Budet (2010), (b) K1440, after drawing in Matteo (n.d.) and (c,d) La Corona Miscellaneous Monument 1 and Copan Stela A, after drawings in Schele (n. d.).

The example in the Wall is a variation involving the inchoative -an, resulting in ‘aj joman ti’ ‘he of the mouth which becomes heat.’ In both cases, the title should be understood as a linguistic figurative reference with the meaning ‘he who is ireful’ (Sheseña, 2020).

Indeed, in colonial and modern vocabularies we find special linguistic figurative expressions that, referring to anger or courage, relate fire to parts of the human or animal body, especially the heart, mouth, face, and head. These metonymies and metaphors of anger in the Mayan languages manifest themselves as type [N + N] diphrasisms composed of the word fire, or other phenomena or objects of the same semantic domain, preceding the word relative to one of the parts of the body, human or animal. In this way they create a third concept: anger. These diphra sistic compounds in turn come to function as qualifiers for a noun to indicate that the latter is “angry.” Consider, for example, the case of Tzeltal k’ajk’al o’tan winik ‘fire-heart man’ > ‘angry man.’ In classical hieroglyphic texts, this type of resource has also been found, e.g., in K1652 we have K’AHK’-‘OHL CHAM k’ahk’ ‘ohl cham ‘fire-heart death’ > ‘wrathful death’ (Sheseña, 2020: 441). We note also that in Yucatec the expression chakaw chi’ ‘hot mouth’ is used precisely to express the idea of anger (Barrera Vásquez, 1980: 78). In classical hieroglyphic texts we find a similar expression to indicate an angry person: ‘AJ-TOK’-TI’ ‘aj took’ ti’ ‘he of the flint mouth’ (K635 and Naranjo Stela 19) (Figure 7b-c). In this case, ‘flint’ is metaphorically equivalent to ‘fire’ in the sense that it is wounding (Sheseña, 2020). Therefore, we propose that the epithets ‘aj jom ti’ ‘he of the hot mouth’ and ‘aj joman ti’ ‘he of the mouth which becomes hot’ should be understood along the same lines as the linguistic metonymies and metaphors of anger.

Wald (2015) notes that the characters ‘aj k’uhuun had a variety of functions at court, including sculptors (aj uxul, Bonampak Lintel 4) and warriors (yajaw k’ahk’, Tonina Monument 140). This shows the high status of the carriers of this title, although this varied from one place to another. In the case of Tonina, these characters stood out even more due to the preponderant role they played in the wars for the territorial expansion of this political entity (Martin and Grube, 2008: 181-185; Sanchez et al., 2019). It is therefore not surprising that one of these characters ‘aj k’uhuun bears an epithet as potent as ‘he who becomes ireful,’ otherwise reserved for kings.

Another possible reference to the epithet appears in the badly damaged Tonina Monument 8 (Figure 5b, grey inset square) where the main theme is the celebration of a period ending by “Ruler 2” in the presence of K’elen Hiix, an ‘aj k’uhuun known to have served the royal court for several decades (Martin and Grube, 2008: 181-185; Sanchez et al., 2019), and the Paddler Gods, the patron gods of Tonina. The proposed TI’ logogram appears to the right of T650 and looks like the beak of a wind god (for another such variant of TI’ see Figure 7d). It is not clear whether this refers to K’elen Hiix or to someone else who attended the ceremony.10

3.3 The Theonym at Yaxchilan and in K9072

At Yaxchilan, T650 appears in a theonym that is part of the long name phrase of Kokaaj Bahlam “The Great”. These examples, together with a similar one on K9072 (Figures 2, 3 and 4), provided the main phonetic clues to the reading of T650. Besides suggesting a reading of JOM, the examples show that the final -si is not working as a phonetic complement but rather as the absolutive -is for unpossessed body parts (Zender, 2004b), in line with other theonyms at Yaxchilan. We note that the reading for the head variant on K9072 is uncertain and accordingly we use an unassuming label “God”. Thus, we propose the literal translation for these theonyms ‘ich’aak jomis chan “BMG” / “God” as ‘the BMG / God whose claw [is] heat in the sky.’ In our view, this ‘claw-heat’ might be understood as a metaphor for “lightning,” thus yielding ‘(the) BMG / God (who is) lightning in the sky’. The same set of dictionary entries presented in the Tonina contexts relating to “heat”, “burning” and “flames” are relevant for this translation.

The use of the absolutive in the compound ‘ich’aak jomis (‘claw-heat’) might initially be unexpected, as it is not anatomically a body part. But not only does it fit in the category identified by Zender as “metaphorical extensions of the king’s body - symbols of his ability to tame nature” (Zender, 2004b: 203-204), it is ratified by the Ch’orti’ belief that “heat” - both physical and metaphysical - is “a part of a human” (Hull, personal communication June 2021). In current indigenous Mayan conceptions, the strength of the person, both physical and moral, is associated with the possession of a certain type of “heat” that is brought with him from birth. This “heat” becomes more intense with age and with the exercise of office: the principals of each community have accumulated enough “heat” and that allows them to occupy the highest positions. The possession of a strong “heat” is visible in the practice of socially correct behavior, in the management of wisdom and courage, and in the ability to relate to various supernatural entities. In the language these conceptions are reflected in expressions such as k’ajk’al winik gobernador ‘brave governor’ (literally ‘hot governor’) (Mendez, 2019: 74), or k’ak’ tepeu ‘inaccessible majesty’ (literally ‘hot majesty’) (Villa, 1985: 189). That is why “heat” endows leaders with a certain power that in turn instills respect and fear among ordinary people (Guiteras,1986: 237; Villa, 1985: 188-189; Sanchez, 1998: 130-133; Page, 2005: 164). In the Yucatecan language, for example, the term k’inam, which derives from the root k’in ‘heat,’ is used in the sense of “virtue”, “strength”, “vigor”, but also “respect” and “fear” (Barrera Vásquez, 1980: 402). We observe the same conceptions among the Nahua (López, 1980). Finally, Hull (personal communication, June 2021, see note 7) states that Ch’orti’ curanderos regard the “heat” of anger as “part of a human”. Thus, jomis may refer to this “heat”.11

In the example of the Kokaaj Bahlam theonym on Yaxchilan Stela 18 (Figure 2c), we may observe a visual play on the homophony between the “heat-related” jom and the “collapse” jom. Here the top part of the T672 hand is jagged and blackened as if the “dark cake slices” of T650 have been expanded to represent a collapsed roof or ceiling with broken edges and ruined interior remaining.

Also at Yaxchilan, we find another relevant theonym in the sculptor’s signature on Lintel 46 (Figure 9). It is spelled ho-ma-la CHAK-ki, likely reading jomal chahk (this form of the final -la is used elsewhere at Yaxchilan, e.g., in the name of Lady K’abal Xook at I1 on Lintel 25 and in the name of K’awiil at B2 on Lintel 39). We propose a translation of ho-ma-la CHAK-ki as jomal chahk ‘Hot Chahk (Lightning).’ The inscription says that the sculptor Tz’ihb Chahk is an assistant (y-an-ab-il ‘his helper’) of a person carrying the titles k’uhul ? ‘ajaw bakab. Here k’uhul is written with an unusual “tamale-eating skull” element that might at first be interpreted as part of the emblem glyph. However, the inscription of Dos Caobas Stela 1 shows that the element simply reads k’uhul, as it appears as part of a clear k’uhul pa’chan ‘ajaw collocation referring to Kokaaj Bahlam. Moreover, recent research suggests that the rare emblem glyph carried by Jomal Chahk, portraying a raptorial bird with another bird’s paw coming out of its mouth, may be associated with the site of Itzimte (Beliaev et al., 2017). The example lends further support to the lightning metaphor in the theonym ‘Ich’aak Jomis Chan “BMG” and its translation as ‘Bloody-Mouthed God whose claw [is] heat in the sky.’

3.4 The Names of Two Kaanul Kings

Two Early-to-Middle Classic kings of the Kaanul dynasty at Dzibanche’ have T650 in their names. They are kings #11 and #17, as listed in the “Dynasty Vase” K6751. We start with king #17, nicknamed “Sky Witness”. In this context, the glyph appears conflated with a ‘UT ‘eye, face’ logogram on Caracol stela 3, on K6751, on the Palenque HS, and at Yo’okop (Figure 10a, c, d, e, and f). On a bloodletting bone from Dzibanche’ (Figure 10b), it appears conflated with CHAN ‘sky’.

Figure 10 (a) Caracol Stela 3, (b) Dzibanche’ bloodletter, (c) K6751, (d) Palenque HS, (e) Yo’okop, (f) Naranjo Stela 47 and (g) Los Alacranes Stela 1. After drawings in (b) Velásquez García (n.d.), (a, c-g) Martin (2005), Martin and Stuart (2009) and Martin et al. (2016).

In some examples, an apparently optional ‘u prefix is present, whereas the bloodletter from Dzibanche’ includes a tu superfix--perhaps a preposition, but more likely a space-restricted phonetic complement following ‘UT (Martin, 2017). The example from the Palenque HS clearly shows the CHUM-like contour of T650, with its body part marker, conflated with ‘UT. In this context, it is obvious that the glyph is to be read. At Yo’okop the CHAN part of the name is not visible, and additional -no (and probable -ma) syllables are represented, perhaps part of a complex confluence with the Yuhknoom title carried by the Kaanul dynasty kings (Martin, 2017). Indeed, Olguín and Velásquez (2013) have proposed a YUK value for the rare hand variant sign T217 based on T217-no-ma spellings in the name of “Sky Witness” at El Resbalón and Pol Box. These in turn substitute for a yu-ku-no-ma spelling preceding the recurring UT[T650] collocation on the Dzibanche’ bloodletter. The reading order in this name is more challenging, as the scribes exercised considerable aesthetic freedom. Nevertheless, examples from the Palenque HS and Naranjo Stela 47 (Figure 10d and f), and from Los Alacranes Stela 1 (Figure 10g) indicate that CHAN should be read last. Martin (2017) reaches a similar conclusion and suggests that the full spelling could be reconstructed from all available examples as YUK-no-ma ‘u-‘UT[T650] CHAN K’AK’-BALAM. With our present understanding of T650, we translate this as ‘fire jaguar (who is the) shaker (of the) eye (which is) heat (in the) sky’. The core phrase, and the focus of our effort, is (‘u-) ‘UT JOM CHAN ‘(the) eye (which is) heat (in the) sky’. Here we would have a metaphor very similar to that in the theonym of Kokaaj Bahlam at Yaxchilan. In the Yucatecan figurative language of emotions, the expression chilak ich refers to ‘anger’ (Bourdin, 2014: 246) and literally means ‘eye that eats or burns’ (ich ‘eye’, chilak ‘thing that eats, stings, burns or burns as a rash, fire or sore’ (Barrera Vásquez, 1980: 99). In this case anger is conceptualized as physical damage caused to another person by “gazing” (Bourdin, 2014: 153), as in “heat” in the “Sky Witness” name. This is a potent metaphor for a gaze that is forbidding, even dangerous. Thus, the name ‘ut jom chan would ultimately mean ‘Wrathful Eye in the Sky.

As for king #11, the only known spellings for the name are T217-CHAN[T650]-kaKAAN (K1372) and T217-CHAN[T650]-ka-KAAN-wa (K6751) (Figure 11). The final -wa in the K6751 example is likely an elliptical spelling for T217-CHAN[T650]-ka-KAAN*K’UH-*KAAN-*‘AJAW-wa, the snake head providing both a part of the name and the emblem glyph. Such compact spellings are common in the “Dynasty Vases.” The spellings involve the T217 hand variant assumed to read YUK. With so few examples available it is not clear if the sign stands for the royal title yuhknoom ‘shaker’ or if it is part of a verbal construct involving an antipassive yuuk ‘shake’. The transcription YUK-[JOM]CHAN-KAAN yuhk[noom]/yuuk jom chan kaan is either ‘(the) snake (is the) shaker (of) heat (in the) sky’ or ‘the snake (who) shakes (the) heat (in the) sky’. As with the foregoing “heat” theonyms, this ‘shaking of the heat’ may be understood as a metaphor for “lightning,” yielding ‘(the) snake (who is) lightning in the sky.’ This is in conformity with the Maya perception of lightning as ophidian in nature - that is, its materialization in the form of K’awiil. For these translations, we refer the reader to the entries related to “heat,” “burning” and “flames” in Appendix 1.

Figure 11 The name of Kaanul king #11: (a) K1372, after photo in Kerr (n.d.), and (b) K6751, after drawing in Olguín (2013).

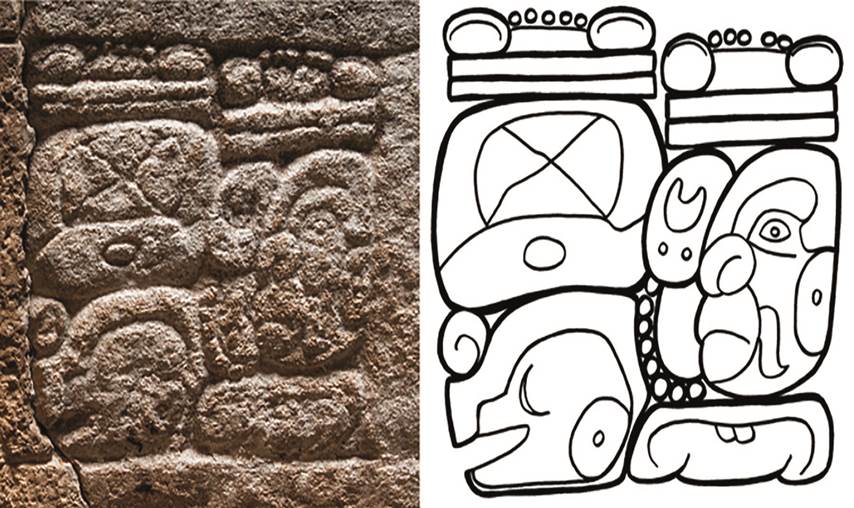

3.5 The Theonym at Tikal

In this context, T650 appears in a theonym that is part of the long name phrase of K’ihnich Waaw and is always conflated with the T20 “top curl” logogram. We understand this as a “Fire-T20[T650]-Sky-God” construct that specifies a particular aspect of the Yopaat storm deity (Figure 12). The as-yet undeciphered sign T20 (in the following cases having an infixed WINIK) is associated with the 4 Ajaw (8 Kumku) Era Day statement on the Early Classic Escuintla Mask, likely from Río Azul, and serves as a unique Glyph D in the Lunar Series of Quiriguá Stela E (east) on the Period Ending date of a solar eclipse (Kelley, 1977). In these contexts, it is certainly a verb, while here we postulate that it is a nonverbal part of the logogram.12 We suggest that K’AK’ and T20[T650] should be equated due to the pattern typical of other fire-initial agent-focus theonyms.

Figure 12 (a) K1261, after drawing in Montgomery (n.d.), (b) K772, after photo in Kerr (n.d.) and (c) vessel from Tikal’s Burial 195, after drawing in Moholy-Nagy and Coe (2008).

In the several examples of the K’ihnich Waaw theonym on ceramic vessels, it is (almost invariably) written as: K’AK’ T20[T650] CHAN YOPAT k’ahk’ X-jom chan yopaat ‘the Yopaat whose Fire is X-Heat in the Sky’ (with X representing T20). However, one example of the theonym (Robiscek and Hales, 1981: 155) features an ergative pronoun u- between k’ahk’ and T20[T650]. So, it is possible that the actual spelling and translation should be: K’AK’-‘u-T20[T650] CHAN YOPAT k’ahk’ u-X-jom chan yopaat ‘the Yopaat whose Fire is his X-Heat in the Sky’. The simplest possible structure for the theonym suggests that T20[T650] may, in fact, be a single sign and an allograph for T650. Were this the case the title would be read k’ahk’ u-jom chan yopaat ‘the Yopaat whose Fire is his Heat in the Sky’. The interpretations presented in the Tonina and Yaxchilan contexts relating to “heat,” “burning” and “flames” are relevant here; to these, we add the Itzaj and Yucatec jom-k’ak’ entries translated as ‘incendiarlo’ and ‘burn with flames of a torch’ (cf. Appendix 1).

Of particular interest is one plate (Figure 13) naming K’ihnich Waaw as the owner. The PSS begins with ‘u-K’AK’-T20[T650] ka-la u-k’ahk’ X-jom lak ‘his Fire-XHeat plate’, with K’AK’-T20[T650] being the same collocation seen in the Yopaat theonym, but now possessed as a noun phrase.

Figure 13 Initial glyphs of the Dedicatory Formula in a plate naming K’ihnich Waaw as the owner, after drawing in Coe (1988: 106).

Also related to this theonym, we note the unusual and telling substitution of the K’AK’-T20[T650] collocation with a “Canoe with Paddler God” logogram (Figure 12c) in a vessel found in Tikal’s Burial 195. This almost certainly names K’ihnich Waaw, as inferred from the archaeological context and from the remainder of his appellatives in the Dedicatory Formula. We suggest this to be an example of artistic virtuosity, the scribe replacing T650 JOM with a homophonous “Canoe with Paddler God” logogram. The absence of k’ahk’ before the “Canoe with Paddler God” might be explained by the elemental (fire vs. water) clash introduced by this playful substitution, but one must bear in mind that an earlier part of the text has been lost due to breakage. Anyone reading the plate would know this to be jom ‘to sink’ as well as johm ‘dugout canoe’ (cf. relevant entries in Appendix 1), and would recognize the theonym. Another example of this very rare “Canoe with Paddler God” logogram appears on an incised shell from Hiix Witz (K4692) in a context that clearly marks the death of an individual, paired with (y-itaj) a second death represented by the common form CHAM-mi cham-i ‘he dies’. These deaths are in turn linked via a Distance Number to the death (k’a’ay u-sakbak y-ik’il ‘ended his vitality and breath’) 104 years prior of a Hiix Witz ruler named utis chan ‘ahk. We suggest that the passage of interest here (Figure 14) reads as follows: ?JOM ti-?YEH-TUN ?-‘AHK jomi ti yeh tuun ? ‘ahk ‘sinks(=dies?) by/with tooth/sharp stone ? Turtle.’ This manner of death “by sharp stone”, possibly suggesting assassination, is observed elsewhere in the corpus of inscriptions. The parallel between the contexts suggests that the logogram “Canoe with Paddler God” is a metaphor for death in the sense of ‘och-i ha’ ‘he entered the water’. The scenes incised on the famous bones from Tikal’s Burial 116 and painted on several ceramic vessels, in which the Paddler Gods steer a sinking canoe that carries the Maize God and animal companions, clearly provide a metaphor for the latter’s death (Stuart, 2016). We thus propose that the “Canoe with Paddler God” logogram is an allograph of T650 representing the intransitive root jom ‘to sink’. In this light, it is perhaps not a coincidence that the idiosyncratic example from Tikal (Figure 12c) was found in a funerary context.

3.6 The Xcalumkin Panels

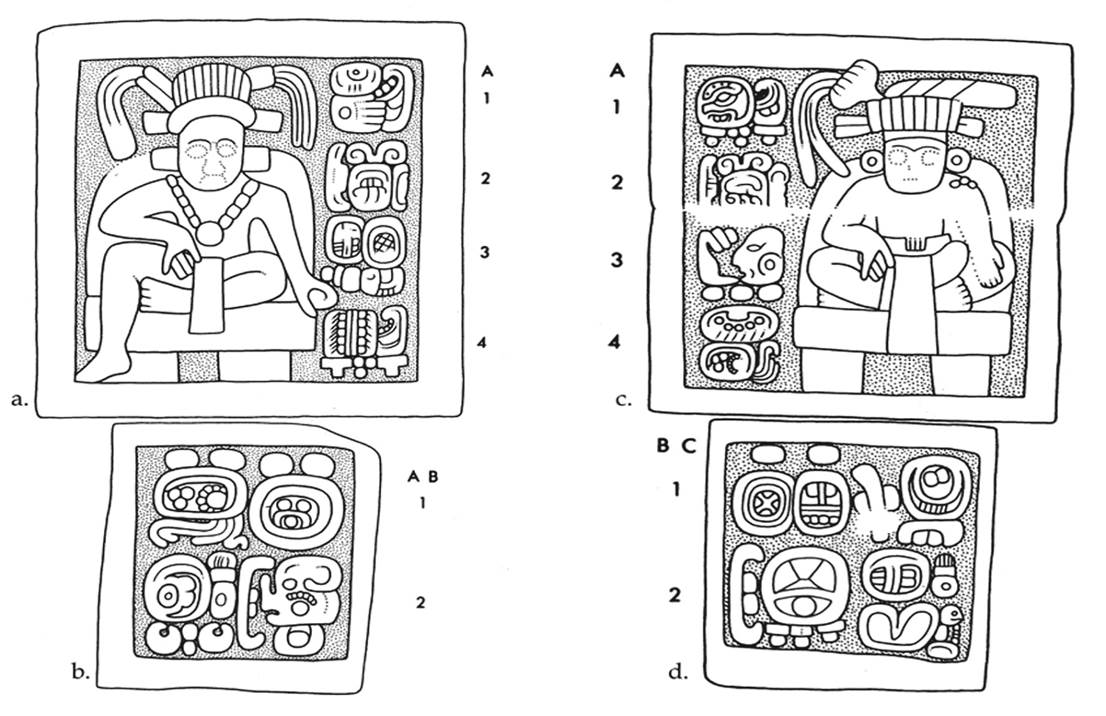

Panels 5 to 8 at Xcalumkin (Figure 15) were placed on an internal wall in the South Building of the Hieroglyphic Group at the site (Grube, 1994; Boot, 1996). They form a pair (5,6 and 7,8) on each side of a doorway between an antechamber and a room in the building. According to Grube (1994: 321), these panels mention two individuals that may have shared power at Xcalumkin in the middle of the 8th century: Kelem Baah Tuun and Kit Pa’. They carry titles such as: sajal (a common court title of unclear meaning), kelem (‘young one’) and baah tuun (a patronym from the province of Ah Canul where Xcalumkin is located) (Boot, 1996 and references therein). In this context, the short text in Panels 7 and 8 can be analyzed as follows (assuming a reading order for Panel 8 of B1-C1-B2-C2, as in Panel 6):

K’AL?-la-ja ‘u-wo-jo-li ke-KELEM-ma ba-TUN-ni

2-TZ’AK CH’AK-ja-li ‘u-JOM-la ki-ti-PA’-‘a

k’ahlaj? u-wojil kelem baah tuun cha’ tz’ak ch’akajil u-jomal kit pa’

‘were fastened, the glyphs of Kelem Baah Tuun;

two compartments (are) across from one another;

it is the passageway of Kit Pa’’

Figure 15 (a-b) Xcalumkin, Panel 5 and Panel 6, drawing by Eric von Euw. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.10.39. (c-d) Xcalumkin, Panel 7 and Panel 8, drawing by Eric von Euw. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.10.40. From Graham (1992).

The overall theme in the four panels is glyphs (u-wojil), carving (‘uxul) and, apparently, in Panel 8, the placement of two sections (cha’ tz’ak) of interior construction (two compartments or rooms, per the plan as described by Grube and Boot) opposing one another (ch’ak[a]jil) separated by a doorway. For the relevant tz’ak entries, Barrera Vásquez (1980: 872) gives ‘juntura, añadidura, tramo’, for which we have elected ‘compartment’ in English.

We propose that the collocation at C1, CH’AK-ja-li, should be analyzed as ch’ak[a]j-il ‘something in a state of being across from something else’, based on the root ch’ak, ‘atravesar a la otra parte’ (Barrera Vásquez, 1980: 122) and the fact that in Ch’olan -aj is an inchoative, here nominalized with -il. This nicely fits the layout of the two interior sections of the building.13 The final two collocations, B2 and C2, specify a ‘passageway’ between the interior chambers themselves - u-jomal kit pa’ - which we would accordingly translate as ‘(it is) the passageway of Kit Pa’’. The relevant jom entries in Yucatecan and Tzotzil are found in Appendix 1.

4. Non-Lexical Examples

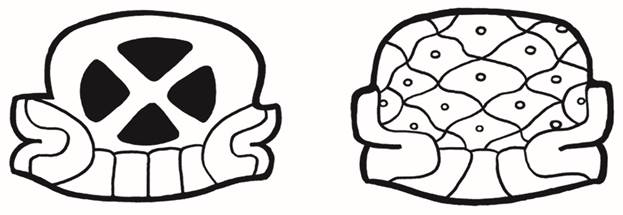

There are several noteworthy contexts for T650 that cannot be explained lexically. In the first case, the term u-k’ahk’ ‘his fire’ substitutes for a variant including T650, perhaps as a visual rebus. In the second, T650 serves to distinguish the hollow turtle shell from the living animal via the meanings ‘hollow’, and ‘hollowed out’ for jom found in Colonial Tzotzil and Yucatecan (see Appendix 1). The final non-lexical examples from the vase K1398 are more elusive, but we offer a rationale below.

4.1 The Palenque Stucco Text

This is a particularly important example since the glyph is part of a well-controlled context found after the Initial Series that refers to fire-drilling rituals associated with gods (Grube, 2000).

The collocation (Figure 16) clearly substitutes for u-k’ahk’ ‘his fire’ in similar contexts. Although the typical outline of T650 is not visible and is replaced by a zoomorphic head that probably represents a censer, the “dark cake slices” and the body part marker are obvious. Given the uniformity of these fire-drilling statements, it is unlikely that the sign is to be read. Instead, we propose that T650 is involved in a visual rebus with “fire” or “heat” as the central concept (cf. heat-related entries in Appendix 1).

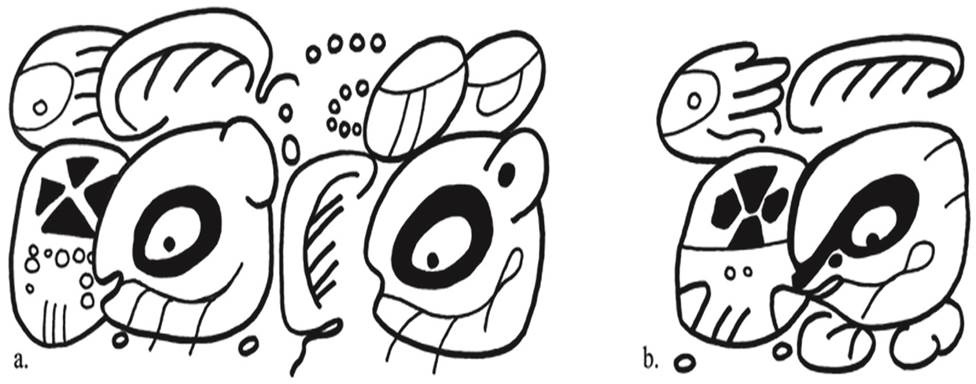

4.2 The MAK Turtle Shells

In these turtle shells (Figure 17), only the black markings of T650 are represented. In this context, they are used simply as decoration, without phonetic value, as the reading MAK for the uninhabited shell is secure (Zender, 2006: 1-14).

We suggest that the “dark cake slices” are a rebus for the hollow turtle shell (cf. entries related to ‘hollow’ in Appendix 1).

4.3 The Regal Rabbit Vase

In the context of K1398, the “dark cake slices” appear conflated with the syllabogram tz’a which is part of a text that intertwines humor, myth, and political (martial) overtones (Carrasco and Wald, 2018).

The text contains references to Bolon Ok Te’ K’uh and the difrasismo Te’ Baah Took’ Baah that are associated with war (also present in the Dresden Codex) and concludes with the following passage (Figure 18):

yi-bi k’e[se]

‘u-TZ’AP[T650]-li-TE’ ‘u-TZ’AP[T650]-li-TUN-ni

y-ib [i]k’es

u-tz’apil te’ u-tz’apil tuun

‘he founds it;

(it is) the planting of the tree, the planting of the stone’

The similarity between this collocation and those of other ‘planting/establishing’ contexts in the Dresden and Madrid Codices suggests that the T650 infixes are a rebus for the planting (u-tz’apil) of trees and stones by making holes (jom (tv)) in the ground14 (cf. entries related to making holes in Appendix 1).

5. Conclusion

The text in the incised shell K8885 - a delightful and personal keepsake of a Classic Maya lord - provides a contextual use of the rare T650 logogram that has been employed to pin down its semantics. The reading ti ni-jomal met ‘to/at my window-nest,’ spoken by the parrot, brings to fruition the combined efforts of epigraphers over more than a decade.

We have explored this instance of the glyph and the available phonetic evidence to propose a phonetic value JOM for *jo[h]m and *jom - a CVhC noun root and a related CVC transitive root with cognates found in many Mayan languages15.

This reading can satisfactorily explain many of the known contexts for T650 with careful attention to the documented semantic domain. As a corollary we identify a homophonous root jom whose Ch’orti’ reflexes reveal a fundamental immaterial property of bodies as perceived by the Maya. As jomis, in the line of wahyis and ‘ohlis, it refers to one’s “inner heat.”

This understanding brings to light an epithet for a court officer at Tonina which adds to the corpus of known metonyms and metaphors involving body parts coupled with fire/heat, and having the general meaning of “wrath, ire.” It also leads to readings for one of the theonyms used by the Yaxchilan king Kokaaj Bahlam, for the theonym of K’ihnich Waaw of Tikal, and for the names of two Kaanul kings, including “Sky Witness.” As corollaries, in the case of K’ihnich Waaw, a playful substitution leads to an important clue about a reading for the rare “Canoe with Paddler God” logogram used as a death metaphor while at Yaxchilan, we identify another theonym involving Chahk in the name of a underlord of Kokaaj Bahlam. Finally, we identify a designation for an interior corridor or passageway in a palace building at Xcalumkin, and we explain the presence of the “dark cake slices” in several non-lexical contexts based on meanings related to heat, holes, and hollow places.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)