Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Salud mental

versión impresa ISSN 0185-3325

Salud Ment vol.32 no.2 México mar./abr. 2009

Conferencia magistral

Training skills for illness self–management in the rehabilitation of schizophrenia. A Family–assisted Program for Latinos in California*

La capacitación de habilidades para el autocontrol de la enfermedad en la rehabilitación de la esquizofrenia. Un programa de asistencia a la familia para la comunidad latina en California

Robert Paul Liberman,1* Alex Kopelowicz1

1 Department of Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Sciences, Semel Institute of Neuroscience and Human Behavior, David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California at Los Angeles

*Correspondence:

Robert Paul Liberman M.D.

UCLA Psych REHAB Program Semel

Institute of Neuroscience & Human Behavior.

760 Westwood Plaza,

Los Angeles, CA 90095,USA.

310–206–1616

E.mail: rpl@ucla.edu

Abstract

This study evaluated the effectiveness of a skills training program designed to teach disease management to Latinos with schizophrenia treated at a community mental health center. Ninety–two Latino outpatients with schizophrenia and their designated relatives were randomly assigned to three months of skills training (ST) versus customary outpatient care (CC) and followed for a total of nine months. The skills training approach was culturally adapted by including the active participation of key relatives to facilitate the acquisition and generalization of disease management skills into the patients' natural environment. There was a significant advantage for the ST group over the CC group on several symptom measures, skill acquisition and generalization, level of functioning and rates of rehospitalization. There were no significant differences between the groups on quality of life or caregiver burden. Skills training had a direct effect on skill acquisition and generalization and utilization of disease management skills led to decreased rates of rehospitalization. Incorporating an intensive, culturally relevant generalization effort into skills training for Latinos with schizophrenia and their families was effective in teaching disease management and viable in a community mental health center.

Key words: Schizophrenia, skills training, behavior therapy, psychiatric rehabilitation, Latino, cultural, skill generalization.

Despite recent advances in pharmacotherapy, the lives of many people with schizophrenia are adversely affected by relapses, hospitalizations, poor social adjustment and an unsatisfactory quality of life. The sub–optimal effects of current medications, even when combined with the customary array of psychosocial treatments, point to the need for developing new biobehavioral interventions (Liberman et al., 1998; Liberman et al., 1999).1,2 Antipsychotic medications and psychosocial treatments that have a broader spectrum of efficacy, are better tolerated, safer, and more readily used by practitioners would improve the outcomes of persons with schizophrenia (Lehman and Steinwachs, 1998; Cabana et al., 1999; Torrey et al., 2001).3–5

The need for improved treatments is particularly urgent for Latinos with schizophrenia, who are rapidly increasing in the population of many regions in the USA (US. Census Bureau 2001).6 Latinos with severe and persistent mental disorders have been shown to have lower accessibility to services, to wait until florid psychotic symptoms arise before seeking treatment, and to use inpatient services disproportionately (US. Department of Health and Human Services 2001).7 Designing, adapting and delivering both pharmacological and psychosocial services for individuals from Hispanic ethnic groups will require cultural competence in professional treaters (Lopez et al., 2001).8

One of the newer, evidence–based approaches to psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia that holds promise for utility with Latino patients and their families is social skills training (Liberman et al., 1986; Liberman et al., 1993; Heinssen et al., 2000).9–11 When made available in modules that are prescriptive and highly structured, as well as focused on teaching patients and their relatives how to manage medication and develop relapse prevention plans, skills training offers the type of authoritative, biomedically–based, and didactically–oriented treatment that has been shown to successfully engage Latinos with schizophrenia and their families in a form of treatment that augments antipsychotic medication (Kopelowicz, 1997).12

While social skills training has been documented as effective in schizophrenia (Benton and Schroeder, 1990; Dilk and Bond, 1996; Heinssen et al., 2000),11,13,14 its efficacy with Latinos has not been formally tested and questions have been raised about its generalization to community adjustment (Halford and Hayes, 1991; Bellack et al., 1984; Penn and Mueser, 1996).15–17 For Latinos with schizophrenia, efficacy and generalization might be promoted by involving family members in the skills training enterprise. It is well established that the vast majority of Latinos with schizophrenia continue to live with their families for many years after the onset of illness (Guarnaccia and Parra, 1996)18 and Latino family members are ideally poised to provide the opportunities, encouragement and reinforcement for using the disease management skills learned by patients in clinic–based sessions (Karno et al., 1987; Jenkins et al., 1992; Guarnaccia, 1992; Kopelowicz et al., in press).19–22

In the current study, which was set in a community mental health center serving a largely Latino area of Los Angeles, we engaged family members to facilitate the acquisition and generalization of disease management skills into the patient's natural environment. The skills taught were from the Medication Management and Symptom Management Modules (Eckman et al., 1990; Eckman et al., 1992; Liberman and Corrigan, 1993; Marder et al., 1996),23–26 translated into Spanish. The primary aim of this randomized, controlled study was to evaluate the effectiveness of combining an educational approach to disease management, involving patients and families in separate venues, with antipsychotic medication for Latino persons with schizophrenia. A control group received medication and treatment as usual only. Because the study was carried out in a typical community mental health center with broad inclusion criteria for patients and with customary staff providing the interventions, the results could be viewed as elucidating <<effectiveness>> rather than the more limited <<efficacy.>>

We hypothesized that, as compared to control subjects, subjects who received skills training would show: 1. greater acquisition, maintenance and utilization of illness self–management skills in their everyday life, 2. lower ratings of psychopathology, relapse and rehospitalization after the training period, 3. higher levels of medication compliance, 4. higher psychosocial functioning, and 5. more realistic and accepting attitudes toward their illnesses. Moreover, we posited a path model in which skills training directly leads to skill learning and utilization, skill utilization directly leads to medication compliance, and medication compliance directly leads to decreased likelihood of relapse. We also hypothesized that, as compared to family members of control patients, family members enrolled in skills training would: 1. express increased optimism and hope with regard to clinical progress and rehabilitation, 2. verbalize less negative statements of a high <<expressed emotion>> nature, and 3. express less burden and higher levels of tolerance for their ill relative's symptoms and problem behaviors.

METHODS

Study participants

A total of 92 patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who were receiving care at the San Fernando Mental Health Center, at Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health–operated Community Mental Health Center located in a large Latino neighborhood of Los Angeles, were recruited into the study from among all current outpatients if they met inclusion criteria. The criteria for selection were an age between 18 and 60 years, a primary DSM–IV chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, at least one episode of treatment in an inpatient facility of at least one week's duration in the previous 12 months, Spanish–speaking, and living with their family. Patients with other concurrent diagnoses (e.g., substance abuse, depression, personality disorder) were not excluded from the study.

Seventy–two participants (78.2%) were diagnosed as having schizophrenia and 20 participants (21.8%) schizoaffective disorder. Sixty–two participants (67.4%) were male. Fifty–five participants (59.8%) were Mexican–American, 29 (31.5%) were from other Central American countries (El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras), and eight (8.7%) were from the Caribbean (Cuba, Puerto Rico). Seventy–four (80.4%) had never been married, eight (8.7%) were divorced or separated, and ten (10.9%) were married. Average age was 38.4 years, and the average education was 8.8 years. Seventy–three (79.3%) lived with their parents, 13 (14.1%) lived with their spouses or ex–spouses, and six (6.6%) lived with a family member other than parents or spouses (e.g., sibling, offspring, cousin). Seventy–six (82.6%) were unemployed at study entry and 16 (17.4%) had a part–time work.

The key relatives were made up of 61 mothers (66.3%), 12 fathers (13.0%), three siblings (3.3%), three offspring (3.3%) and 10 spouses (10.9%) and three ex–spouses (3.3%). The average age of the key relatives was 58.6 years, and their average education was 7.6 years. Nine (9.8%) of the relatives were born in the United States. Ten (10.9%) of the relatives were illiterate in English and Spanish. The characteristics of the sample ultimately selected for this study did not significantly differ on any clinical or demographic variables from the more than 500 Latinos with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who were served by the community mental health center.

Procedures

All procedures and informed consent documents for the study were reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Protection Committee of the UCLA School of Medicine's Office for Protection of Research Subjects and the Human Subjects Research Committee of the Los Angeles County

Department of Mental Health. After patients and family members agreed to participate in the study and signed an informed consent, patients were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV (SCID–IV; First et al., 1995)27 by a research psychologist trained and maintained to meet high standards of reliability by the UCLA Clinical Research Center for Schizophrenia and Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Patients were then administered a battery of instruments, described below, including scales measuring psychopathology, medication compliance, attitudes towards illness, quality of life, level of psychosocial functioning, and disease management skills. Family members completed scales measuring 1. level of expressed emotion, 2. caregiver burden, and 3. hope for the future. Patients and their key relatives were then randomly assigned to either continue treatment as usual (N=47) or to participate in skills training with generalization along with treatment as usual (N=45).

Interventions

Experimental treatment. Patients were assigned to groups of six for their skills training based on successive referral from intake into the study. Skills training groups met for ninety–minute sessions four times per week during three months; two days apiece were dedicated to each of the two modules, Medication and Symptom Management. Each module comprised a Trainer's Manual, Participant's Workbook and a videocassette with thoroughly specified psychoeducational material and training techniques to teach participants instrumental, social, and problem–solving skills. The Trainer's Manual specified what was to be said and done to teach a module's skills; the Participant's Workbook included written material, forms, and exercises to help participants learn the skills; the videocassette illustrated the behaviors to be learned; and the User's Guide included technical information needed by staff in preparing to use a module.

The Medication Management module was divided into four skill areas: 1. obtaining information about antipsychotic medication, 2. recognizing its side effects, 3. monitoring these side effects, and 4. negotiating medication issues with physicians and other caregivers. Breaking this down further, in the <<Negotiating Medication Issues>> skill area, for instance, there were several requisite behaviors to be learned, including a pleasant greeting of the healthcare provider, followed by presenting any medication problems in very specific ways. In turn, the latter included telling the onset of side effects along with their extent of discomfort; making a specific request for action with repetition and clarification; asking about the expected time for effects if changes were made in the drug regimen; and thanking the psychiatrist for the assistance provided with good eye contact, good posture, and clearly audible speech.

In the Symptom Management module, patients learned how to identify the warning signs of relapse, how to intervene early to prevent relapse once these signs appeared, how to cope with the persistent psychotic symptoms that continued despite medications, and how to avoid alcohol and drugs of abuse. Again, each skill area could be further divided into target behaviors. In the <<Warning Signs>> skill area, patients learned how to discuss warning signs with their doctor and relatives so that agreement could be reached on the symptoms that predicted relapse (e.g., insomnia, irritability, social withdrawal and ideas of reference). Patients were also taught to keep a checklist of warning signs to monitor themselves over time. This is designed to help patients understand the benefits of early intervention and realize when to request help. For those patients who were illiterate in both English and Spanish, extra efforts were made to assure that the material was learned, inc1uding the use of pictographic representations of the various warning signs identified.

Patients proceeded through each skill area using the same seven learning activities. The first learning activity, introduction to the skill area, described the specific skills that were to be taught and the benefits participants could expect if they used them. The trainer, whose discipline was either nurse, psychologist or social worker, then demonstrated these skills by conducting the second learning activity, video–assisted modeling. The trainer played the module's videotape that showed peers, who were actors, performing each of the area's skills. Selected questions were then asked to ascertain that patients understood the material. After the skills had been demonstrated, the trainer conducted the third learning activity, role playing. Each participant was asked to role play the skills that had just been demonstrated. Role plays were videotaped, which was used to provide feedback. In the fourth learning activity, resource management, participants responded to prepared questions from the Manual to learn how to identify and obtain the resources they will need to perform the skills in the real world. The fifth learning activity, solving outcome problems, was devoted to a full implementation of problem solving (D'Zurilla, 1986).28 Patients learned to apply this method to problems encountered when putting into practice the relevant skills. In the sixth learning activity, in–vivo exercise, participants carried out contrived exercises to practice the acquired skills outside of the training session. The trainer accompanied the participant to coach him/her by providing encouragement, support, and positive feedback. The trainer conducted the seventh learning activity, homework assignments, in much the same manner except that the participants performed the skills on their own in the <<real world,>> and provided <<evidence>> that they had completed the assignments. More detailed descriptions of these modules can be obtained from other publications (Liberman et al., 1993; Liberman and Corrigan, 1993).10,25

To ascertain that the modules were being conducted systematically and correctly, a therapist fidelity evaluation form was used (Wallace et al., 1992).29 This form included a general section assessing overall therapist competency, as well as specific items that pertain to mastery of each individual module content area. Prior to starting the study, raters were trained to high levels of competency on this scale, demonstrating at least 90% of the key techniques required by the module procedures. They were monitored for maintenance of fidelity throughout the study and given feedback when diverging from the 90% level.

In the experimental condition, family members of patients were included in weekly <<generalization sessions>> aimed at utilizing relatives as generalization agents. These group sessions used the modules as focal points for educating relatives as coaches for their ill family member. Relatives were thoroughly informed about the skills the subjects had been taught in each module, as well as the problem solving skills and homework exercises that were provided. The relative was then assisted in mapping these skills to the patient's environment by examining how the home environment could provide opportunities for skill use. For example, a place, such as a bulletin board or the refrigerator, was identified where a copy of the Side Effects Checklist could be displayed for convenient completion by the patient on a daily schedule as prescribed in the Medication Management Module. The prescribed steps to be followed by the relative on how to coach the patient in the use of the Checklist were also covered. In essence, relatives were trained to offer opportunities, encouragement and reinforcement to their mentally ill relatives for applying the skills in everyday life. Equally essential to this training was that relatives would never take over the patients' responsibilities; for instance, they were instructed to not complete the Side Effect Checklist for the patient.

A third important method for relatives' amplifying generalization, namely monitoring and reinforcing the use of the skills by the patient, was instituted. The relatives were instructed to set aside time each week to discuss adherence to the module's skills and learning activities with the patient and resolve obstacles that impeded performance. Most importantly, the relative was asked to, for instance, use a checklist to verbally reinforce the patient for successful performance. Pictorial representations were used with illiterate relatives. The use of praise was thoroughly explained, modeled, and practiced using role plays. In addition, two home visits were conducted during the follow–up period; the first one about one month after the skills training and the second four months later. The purpose of these visits was to review progress and help solve problems identified by the therapist, the family or the patient in the process of transferring the skills to the home environment. Specific problem solving exercises were conducted to address the identified difficulties. The therapist offered support and encouragement for continued use of the skills.

The wording of items on the training materials, checklists and monitoring sheets, and the training procedures were culturally adapted for use with the study population (Leslie and Leitch, 1989).30 This process was thoroughly described in detail in another paper (Kopelowicz, 1997).12 In brief, cultural adaptations included but were not limited to translation and back–translation for Spanish–speakers in Southern California using focus groups of bilingual patients to determine appropriate translations; the use of indigenous, bilingual and bicultural staff of the community mental health center as skills trainers; and an informal personal style by skills trainers with patients and relatives that included the sharing of food and encouragement of <<small talk>> before and after training sessions. These adaptations were made to encourage warm interactions between skills trainers, patients and relatives, thereby increasing subject retention in the study, as well as enhancing the overall effectiveness of the intervention.

Control treatment. The comparison group, as well as those in the skills training groups, continued to receive treatment as usual. The San Fernando Mental Health Center is a community agency that provides case management by social workers and monthly psychiatric visits for medication management using a multidisciplinary team approach. The clinically stable patient typically attends a 20–minute appointment with a psychiatrist once a month. As patients enrolled in this study needed other treatment or rehabilitation modalities, other members of the treatment team were consulted. For example, if a patient faced eviction, the social worker facilitated the patient's efforts to solve the problem, or, depending on the level of functioning of the patient, resolved the situation for the patient. If a patient expressed desire to seek employment, the rehabilitation counselor assessed, trained and placed the patient in the appropriate vocational setting. Finally, if patients experienced an exacerbation of symptoms, contact with the psychiatrist and/ or psychiatric nurse increased (either at the Center or in the <<field>>) until the patient was stabilized. For the patients who were clinically decompensating too rapidly to be treated as an outpatient, a liaison was made between the Center and the local county hospital for inpatient admission. These interventions are the standard of care in the mental health centers administered by the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health.

Assessments

All measures were gathered at baseline, at the end of the three–month active treatment phase, and after a six month follow–up period, unless otherwise stated below. Measures were appropriately translated and adapted for use with the Spanish–speaking, Latino population by a work group chaired by the first author as described in detail in another paper (Kopelowicz, 1997).12 Scales that assess psychopathology are generally normed to white, middle class, urban groups and must be appropriately adapted for sensitive use by Latino patients and their relatives (Lopez, 1994).31

Separate raters were used to assess patients and relatives. All of the raters were blind to the treatment condition of the patients and relatives. To ensure blindness, the raters were instructed to remind patient and relative subjects at each visit to not disclose what kinds of treatment they were receiving. Additionally, the assessments were conducted in an area removed from the study's clinical activities to minimize the chances that the raters would have access to information that could break the blind.

Patient measures. Psychiatric symptoms were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987).32 This instrument provides subscale scores on positive psychotic symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions, thought disorder), negative psychotic symptoms such as anhedonia, apathy, alogia, avolition and social withdrawal, and general symptoms including depression and anxiety. The Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health's Management Information System (MIS) was used to collect information on rehospitalization rates. Rehospitalizations are captured by the MIS in county hospitals, as well as private, non–profit hospitals with psychiatric units under contract to Los Angeles County. Medication adherence was assessed by monthly pill counts, patient reports, family reports, and monthly interviews with treating psychiatrists. The criterion for adequate adherence was set at having taken at least 80% of prescribed medication as determined by all four of these sources in the month preceding the post–intervention assessment.

The measure of social functioning was the Independent Living Skills Survey (Wallace et al., 2000),33 completed by the key relative. This survey includes 103 items that provide a functional assessment of patients' instrumental living skills in 12 areas of basic community living skills: personal hygiene, appearance and care of clothing, care of personal possessions and living space, food preparation, care of one's own health and safety, money management, transportation, leisure and recreational activities, job seeking, job maintenance, eating behaviors, and social interactions. Informants indicated how frequently an individual had performed each skill within the past month and how much of a problem the behavior (or lack of it) had been for the family on a five–point scale. At the end of the ILSS, the key relative rated the person's overall social adjustment (global score) on an 11–point scale in which a higher score reflects better social adjustment. The ILSS has adequate psychometric properties (Wallace et al., 2000),33 including internal consistency (alpha coefficient ranged from good to excellent) and concurrent validity with the Global Assessment Scale (r=.268, p<.01). In addition, the ILSS demonstrates good agreement (r=.444) between two independent sources of information (e.g., patient and parent).

Subjective satisfaction was assessed with the Quality of Life Interview (Lehman et al., 1982).34 This instrument assesses the level of satisfaction using a Likert scale of seven anchors ranging from <<terrible>> to <<delighted>>. The nine subjective subscales assess satisfaction with living situation, family relations, social relations, leisure activities, finances, legal–safety issues, work–school issues, health issues and overall quality of life.

The patients' attributions of the reasons for their level of adherence to pharmacological treatment were assessed with the Rating of Medication Influences Scale (ROMI; Weiden et al., 1994).35 The ROMI assessed patients' estimates of the extent to which adherence to medication was influenced by their attitudes and beliefs about perceived well–being, relationship with treatment team, relationship with family members, risk of relapse and hospitalization, social and financial pressures, and medication effects. The 23 items of the ROMI are rated on a three–point scale (no influence–mild, influence–strong influence). The ROMI possesses adequate psychometric properties in terms of interrater reliability (range=.76–1.00).

Knowledge and skills in medication and symptom management were assessed through interview and role–play exercises with the Medication Management Module (MMM) Test and the Symptom Management Module (SMM) Test, respectively. The MMM Test includes 32 items and the SMM Test includes 40 items scored on a two– or three–point scale wherein the maximum score is 34 and 43, respectively. Previous field trials indicated that the MSTT could be reliably administered and scored (three–month test–retest interval ranged from .64 to .87 and the interrater agreement ranged from .93 to .98), and was sensitive to changes achieved with module prescription (Wallace CJ, unpublished manuscript). To evaluate generalization of medication and symptom self–management skills, the Medication Management and Symptom Management Skills Generalization Assessment was used (Liberman et al., in press).36 This instrument discerned whether patients were using their recently learned skills in their natural environments. The Medication Management Module Generalization Assessment includes 15 items with a maximum score of 39 points and the Symptom Management Module Generalization Assessment includes 10 items with a maximum score of 22 points. The MMM Test, the SMM Test and the Generalization Assessments were used at the previously mentioned intervals.

Family measures. Patient's skill development was expected to kindle family members' optimism about their relative's clinical progress and rehabilitation. This was measured using a 20 item, five–point Likert–type Hope for the Patient's Future Scale in which a higher score indicates more hope. The Hope for the Patient's Future scale was created for this study and adapted for the study population from the Miller Hope Scale (Miller and Powers, 1988),37 an instrument originally developed for patients with medical' illnesses. The Hope for the Patient's Future Scale includes items focused on family members' expectations for improvement in terms of their ill relatives' symptoms, coping skills, adherence to treatment, social and vocational functioning, relationships with family members, and overall quality of life. The Miller Hope Scale has adequate psychometric properties, including internal consistency alpha coefficient of .93, two week test–retest reliability of .82, and good criterion–related construct validity with several established instruments (r=.70 or above).

The attitudes and feelings family members expressed about their mentally ill relative (<<expressed emotion>>) were evaluated with the Five Minute Speech Sample (Magaña et al., 1986).38 Each key relative was asked to speak without interruption for five minutes about <<What kind of person (the patient) is and how you two get along together>> or the same phrase in Spanish if the relative indicated that Spanish was his or her preferred language. The interviewer then turned on an audiocassette recorder and remained in the room while the key relative responded for five minutes. The relative was not prompted for the entire five–minute period unless he or she would stop talking for more than 30 seconds, or ask any question. In such cases, the interviewer would repeat the original question. All FMSS ratings were completed by a trained rater who was blind to the purposes of the study. The speech samples were coded according to a system developed and validated in English and Spanish by Magaña et al. (1986),38 and rated only on the basis of critical comments. The criteria for a rating of high EE based on criticism are any of the following: 1. a negative initial statement, 2. an overall negative rating for the patient–relative relationship, or 3. one or more critical comments about the patient. To assess reliability, an additional experimenter rated 10 randomly selected audiotapes. The kappa for interrater reliability was calculated as .90. This brief method reasonably corresponds to the <<gold standard>> for expressed emotion, the Camberwell Family Interview (Vaughn and Leff, 1976),39 and has been shown to have predictive validity in the course of mental disorders (Asarnow et al., 1993).40

The family's ability to cope with their ill relative's disruptive behaviors was assessed with the Family Burden Interview Schedule (Pai and Kapur, 1981).41 This semi–structured interview schedule consists of 24 items divided into six categories of burden: financial, effect on family routine, effect on family leisure, effect on family interaction, effect on physical health of other family members, and effect on mental health of other family members. Each item could be recorded as no burden (scored zero), moderate burden (scored 1) or severe burden (scored 2). The Family Burden Interview Schedule has been demonstrated to have good psychometric properties including interrater reliability above 87% on all items and excellent concurrent validity (r=.72) with an overall objective burden assessed by independent raters (Pai and Kapur, 1981).41

Statistical analyses

Separate analyses of covariance were performed on each outcome measure, using the baseline score as the covariate and treatment condition as the independent variable (ST versus CC). A separate ANCOVA was performed for each assessment point (post–training and six month follow–up). A post hoc path analysis was done to evaluate a mediating model of treatment effects on relapse risk. Because that analysis was post hoc, and depended on the results of other analyses, methodological details of the analysis are presented below with the presentation of results. All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical library.

RESULTS

Forty–five subjects were randomized to the skills training condition and 47 to the comparison group, treatment as usual. Of the 45 participants randomized to the skills training condition, 39 completed the study protocol and had data gathered at all three assessment points. Of the six non–completers, two patients dropped out because they obtained full time employment and were thus unable to participate. Two others dropped out because the key relative was unable to attend the family sessions and were unwilling to schedule <<make–up>> sessions. The remaining two patients, as well as two non–completers in the control group, withdrew informed consent after undergoing baseline assessments. Baseline comparisons were conducted with all 92 subjects who were randomized, but all subsequent analyses included only those subjects who were assessed at all three time points (skills training: N=39; comparison: N=45). The 39 subjects in the skills training group who were assessed at all three time points attended more than 90% of the skills training sessions. Regular attendance was facilitated by the provision of transportation for all study participants.

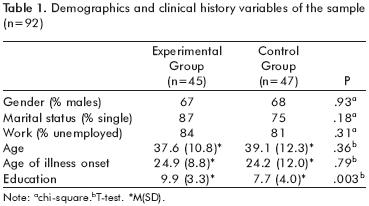

There were no statistically significant differences between treatment conditions on any of the demographic or clinical history variables (table 1) except for level of education in which skills training participants had on average two more years of education than those receiving customary care (t=2.99; df=l,90; p=.003). Regarding skills knowledge and generalization, as well as all other outcome variables, the skills training and customary care groups did not differ at baseline.

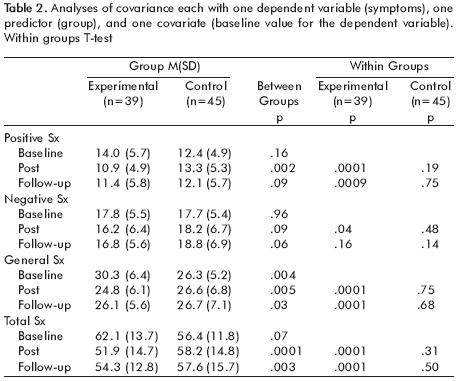

Psychopathology. There was a Group x Time effect on positive [F=7.25, df=2, 159, p<.001], negative [F=3.77, df=2, 159, p<.05], and total symptoms [F=1O.78, df=2,159, p<.0001] with ST subjects demonstrating significant decreases across all three symptom categories, while CC subjects showed no difference from their baseline symptom levels at post–intervention or six month follow up. As shown in table 2, ST participants demonstrated significantly reduced positive, negative and total symptoms immediately after the three month intervention period, and maintained lower levels of positive and total symptom scores at six month follow–up.

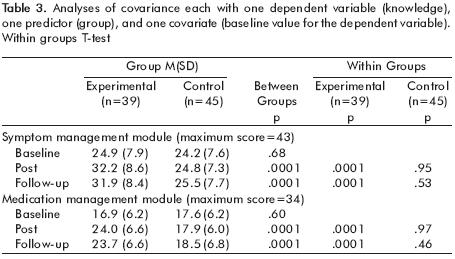

Skill acquisition and durability. There was a significant main effect for group on skill acquisition for both Medication Management skills [F=46.38, df=1,81, p<.0001] and Symptom Management skills [F=41.3, df=1,79, p<.0001]. As shown in table 3, ST subjects learned the material presented in the training sessions and retained their knowledge through the nine–month follow–up assessment while CC subjects showed no change from baseline on either variable.

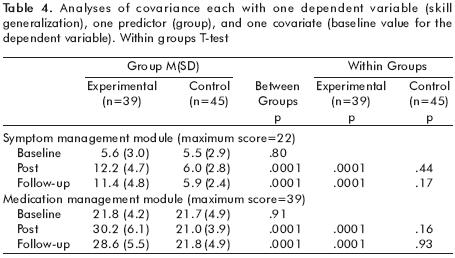

Skill generalization. There was a significant main effect for group on skill generalization for both Medication Management skills [F=79.78, df=1,81, p<.0001] and Symptom Management skills [F=56.44, df=1,73, p<.0001]. As shown in table 4, ST subjects increased their generalization of skills and continued to use these skills in their everyday lives, while CC subjects demonstrated no change from baseline on either variable.

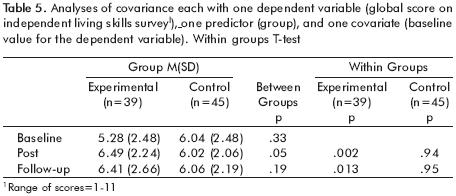

Level of functioning. There was a significant within group main effect on the global score of the ILSS [F=3.98, df=1,82, p<.05]. As shown in table 5, ST subjects improved significantly from baseline to post–intervention (t=3.33, p=.002) and from baseline to follow up (t=2.62, p=.013), but CC subjects did not. Between group comparisons showed an advantage for the ST group over the CC group at post–intervention (t=1.98; p=.05), but not at follow up (t= 1.33, p=.19).

Quality of life. There were no significant main or interaction effects on the Lehman Quality of Life Interview. Within and between group comparisons revealed no significant differences at any assessment point, nor any improvements from baseline to post–intervention or follow up for either group.

Attitude towards medication. There were no significant main or interaction effects on the Rating of Medication Influences Scale. Within and between group comparisons revealed no significant differences at any assessment point on any of the 23 items, nor any improvements from baseline to post–intervention or follow–up for either group.

Adherence to medication regimen. At post–intervention, participants in the ST group (33/39; 84.6%) were not more likely than CC subjects (35/45; 77.8%) to have been adherent to their medication regimens. There were no statistically significant changes from baseline to post–intervention or follow–up for either group.

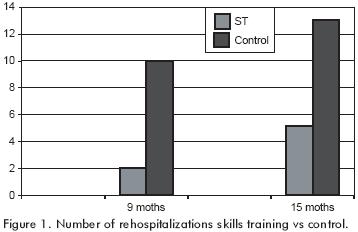

Rehospitalization. There were significant differences between the groups on hospitalization rates during the study period (from baseline to follow–up). As shown in figure 1, while only 2 of the 39 (5.1 %) individuals in the ST group were hospitalized, 10 of the 45 (22.2%) individuals in the CC group were hospitalized. During the subsequent six months (from follow–up to 15 months after the start of the intervention), data from the MIS of Los Angeles County revealed that three more subjects from each group were hospitalized.

Family measures. There were no significant main or interaction effects on the Hope for the Patient's Future Scale or the Family Burden Interview Schedule. Within and between group comparisons revealed no significant differences at any assessment point. Responses of family members in both the ST group and the CC group were consistent throughout the study period with low levels of family burden (range of mean scores =8.8–14.2 on a scale of 0–48) and high levels of hope for the future (range of mean scores =70.2–76.1 on a scale of 20–100). There were no differences between groups at any of the time points on expressed emotion. Approximately 30% of the key relatives were rated as high in expressed emotion at each assessment.

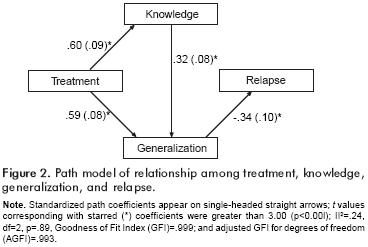

Because the results confirmed that ST reduced relapse risk and resulted in increased skills and generalization, a post hoc path analysis was done to evaluate the hypothesis that treatment effects on relapse were mediated by acquisition and utilization of skills. Notably, the model does not include medication compliance. This is not to say that compliance is not related to relapse. However, since treatment did not affect compliance, it could not be a mediator of any treatment effects on relapse. We note that path analysis can not <<prove>> a model. It can, however, indicate that a model is implausible (i.e., reject a model), and can yield evidence as to how well a given model <<fits>> the observed data. Models that fit well should have high indices of goodness of fit, and small chi squares which indicate that they can not be rejected and are plausible.

The path analysis proceeded as follows. First, all linear influence of pre–treatment levels of knowledge and generalization on these variables was removed by performing separate multiple regression analyses on each of them on baseline knowledge and generalization scores. The residuals from these analyses were entered into the subsequent path modeling. Use of these <<baseline–adjusted>> scores is analogous to the use of baseline as a covariate in analysis of covariance. The path analysis was done with SAS CALIS, a general structural modeling program and the results are presented in figure 2. Standardized coefficients are reported below because they are more directly comparable with each other than unstandardized coefficients. The model yielded a goodness of fit chi square with two degrees of freedom, which represent the two omitted paths: a. from treatment directly to relapse and b. from knowledge to relapse. Omission of a direct path from treatment to relapse tests the hypothesis of complete mediation (i.e., that treatment effects on relapse are entirely accounted for by its effects on skills acquisition and generalization). Also, the model posits that knowledge affects relapse only when it is used.

DISCUSSION

By involving relatives of Latino patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in a culturally relevant, disease management program based on skills training techniques, it was possible to obtain favorable outcomes in key domains of psychopathology, relapse, rehospitalization, and social functioning. Moreover, these positive outcomes were seen for six months after the end of training and accrued in a cohort of individuals who were representative of the full spectrum of patients being served in a typical catchment area's mental health program and through services provided by line level staff.

The present study replicates and extends into the cross–cultural arena the findings from three recent studies of social skills training in schizophrenia which suggested that generalization of skills training was facilitated through the use of trained clinicians (Liberman et al., 1998; Liberman et al., 2001)1,42 and indigenous community supporters (Tauber et al., 2000; Glynn et al., in press).43,44 Three factors may have played a role in the positive results on generalization that were reported by the investigators of these studies and which appear to contradict those researchers who have had less success in achieving a transfer of effects of skills training in the patients' everyday lives: a. use of a highly structured and prescriptive training technique that compensates for neurocognitive deficits and symptoms of schizophrenia; b. employment of skills trainers whose quality of training is assured through the use of a fidelity scale; and c. deployment of clinicians or natural supporters who are taught to promote opportunities, encouragement, and reinforcement for the naturalistic use of the skills learned in the clinic.

Each of the previous studies also utilized the modules from the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills Program (Liberman et al., 1993; Kopelowicz and Liberman, 1998).10,45 The procedures and format used for training the skills of each module were designed to compensate for the cognitive and symptomatic interferences with learning commonly found in schizophrenia, thus allowing participants with <<learning disabilities>> to acquire and practice skills in the training sessions and in the <<real world>>. The learning activities used in the modularized skills training integrated the following techniques which have been shown to be effective in compensating for the neurocognitive and symptomatic problems of persons with schizophrenia: social modeling, self–as model, video feedback, abundant positive reinforcement, prompting, coaching, presentation of knowledge and skill through multiple sensory channels, repetition, shaping, minimization of errors, and procedural or implicit learning (Liberman et al., 1982; Eckman et al., 1992; Liberman, 2001).24,46,47

A number of studies of psychosocial treatments of persons with schizophrenia and other severe and persistent mental illnesses have shown that naturalistic outcomes, such as employment in the competitive marketplace, are more likely to occur when the designated treatments are delivered with fidelity to the program's manual or protocol (Becker et al., 2001; Bond et al., 2000; McHugo et al., 1999).48–50 For skills training, critical elements that clinicians must adhere to in the training process include use of annotated modeling, guided practice of the skills with repetition until satisfactory role plays are achieved, use of problem–solving so that the inevitable obstacles to using the skills that occur in the community can be removed, and continuing with training until autonomous use of the skills in homework assignments has been demonstrated by the patient. When <<short–cuts>> are taken by trainers, such as deleting the role playing and videotape feedback, desired outcomes may not occur (Wallace et al., 1992).29

One reason for the frequent failure to demonstrate generalization of skills either to the natural setting or to global functioning is that generalization techniques are often not built into the skills training enterprise. Generalization techniques include providing support to the trainer as he or she attempts to adapt the newly learned skills to fit the living environment, encouragement to try the skills in that environment, and assistance when the attempt to use the skills is unsuccessful. Subjects paired with specially–trained case managers who work with them in their own environments to create personalized prompts and reinforcers in the community for skills that had been initially learned in the skills training session demonstrate improved social adjustment in the community, better social functioning, lower relapse rates and higher subjective quality of life (Liberman et al., 1998; Liberman et al., 2001).1,42 Residential care staff have also been utilized to facilitate generalization with salutary effects on interpersonal functioning (Tauber et al., 2000) .43 In addition to improvements in these domains, subjects who received skills training in the present study also manifested decreased symptoms at post–intervention and at six month follow–up. This finding is noteworthy because a frequent criticism of skills training for individuals with schizophrenia is that the effect is lost after the training is completed. The use of family members as generalization aides may have served to increase the durability of the effects of skills training.

The present study also tested a mediational model to ascertain how skills training may improve outcome, in this case, relapse prevention. The results of the path analysis model suggest that the intervention directly enhanced skill learning and that skill utilization resulted directly from the increased skills learned, as well as from the intervention itself. The finding that the intervention used in this study had direct effects on skill learning and utilization is plausible given that it included two separate but integrated components, that is, skills training for individuals with schizophrenia plus generalization training for their key relatives. However, because this study did not include a group receiving skills training or generalization training only, it is not possible to tease out the relative benefits of each of these treatment components.

An important result from the path model was that the utilization of skills, not their acquisition, was directly related to decreasing the risk of relapse. This finding has several implications for future work related to skills training for schizophrenia. First, it illustrates the need for studies on skills training to include measures of skill utilization, rather than just skill learning, as is most commonly done (Heinssen et al., 2000).11 Second, it highlights the critical role of skill utilization in affecting a variety of more distal outcomes such as symptom reduction, relapse prevention, and level of social functioning. Third, this finding supports the need to build a generalization strategy into the skills training enterprise; that is, patients should be afforded opportunities for using newly learned skills within their natural environments and skill performance should be prompted and reinforced by external agents.

While we initially hypothesized that the salutary effect of illness management training on relapse prevention would be mediated by increased medication compliance, we found that the intervention reduced relapse risk independent of medication compliance. One explanation for this was the initially high level of medication compliance; a ceiling effect immune from any skills training effects. It is possible that the tendency for Latinos to be more compliant with their medication regimens (Hosch et al., 1995)51 and their involvement in a research study with periodic assessments of their medication use contributed to this ceiling effect. Another explanation for the reduction of relapse and rehospitalization in the experimental group was that the use of illness management techniques learned in the skills training groups served as a <<protective factor>> to buffer the effects of biopsychosocial stress and vulnerability. For example, subjects who learned and used symptom management skills may have been able to recognize their warning signs of relapse (Skill Area 2) and activate their emergency plan (Skill Area 3) to forestall a hospitalization. Such an explanation is consistent with the known benefits of the skills training modules (Wirshing et al., 1992).52

The ST intervention did not produce differential benefits on quality of life. Failure to find improvements on quality of life is consistent with most studies of skills training for schizophrenia (Heinssen et al., 2000)." Psychiatric rehabilitation techniques are generally viewed as domain specific, that is, the benefits are directly related to the targeted area of training. For example, antipsychotic medications improve symptoms of schizophrenia, vocational rehabilitation improves work outcomes, and assertive community treatment decreases rates of hospitalization. Similarly, the focus of the training in this study was to enable patients to acquire, maintain and generalize disease management skills. Although the use of such skills may play a role in improving quality of life, other factors, such as depression, substance abuse, homelessness, poverty and unemployment are more germane to quality of life among individuals with schizophrenia (Lam and Rosenheck, 2000) .53

Nor did the ST intervention produce any changes on patients' attitudes towards their medications. One possible explanation for this finding is that these attitudes were overwhelmingly positive at baseline, thus leaving little room for improvement. At all three assessments, patients strongly endorsed statements from the ROMI such as <<My medication helps me feel better>> and <<My medication prevents relapse>> and only weakly agreed with statements such as <<I am embarrassed to take medications>> and <<The side effects of my medication bother me>>. This explanation is further supported by the high rates of medication adherence found across groups as adherence has been found to correlate with positive attitudes towards medications (Fenton et al., 1997).54 The results of the present study suggest that skills training in disease management can be effective for stable outpatients with schizophrenia across a variety of outcomes without changing attitudes towards medication or increasing adherence to medication regimens. We are currently embarked on a follow–up study to determine whether schizophrenia patients with negative attitudes towards medication and poor adherence to their medication regimens would benefit similarly from a skills–based, disease management approach.

Contrary to expectations, why did we not find changes from baseline in family members' expressed emotion, hope for the future, and caregiver burden? One explanation for these findings is the floor and ceiling effect. The family members who participated in this study generally reported low levels of expressed emotion, positive expectations for the future and low caregiver burden which is consistent with previous studies of Latino populations (Jenkins and Karno, 1992).55 Another possible reason for the intervention's lack of impact on the family members' attitudes is that the relatives were not the object of the intervention, but rather served in this project as auxiliary clinicians; that is, the main aim of the sessions with relatives was to teach them how to help their ill relatives patients learn and utilize disease management skills. Therefore, the domain specificity of the skills training may have mitigated any direct effect on the attitudes of the family member (Liberman, 1992).56

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Maria Castillo, RN; Maria Panduro, BA; Jaime Solis, LCSW, and Melinda Hoffman, BA, for their collective efforts in conducting the skills training; Sun Hwang, MS for the data analyses; Charles J. Wallace, Ph.D., Steven R Lopez, Ph.D., and Michael Goldstein, Ph.D. (deceased) for consultation; and the patients, families and staff of the San Fernando Mental Health Center for their participation and support of this project. The study was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health Small Grant (MH 56026) to Dr. Kopelowicz and by the VCLA Clinical Research Center for Schizophrenia and Psychiatric Rehabilitation (NIMH Grant MH 30911; Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., Principal Investigator).

REFERENCES

1. Liberman RP, Marder SR, Marshall RD, Mintz J, Kuehnel T. Biobehavioral therapy: Interactions between pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy in schizophrenia. In: Outcome and lnnovation in psychological treatment of schizophrenia. Wykes T, Tarrier N, Lewis S (eds.). London: John Wiley & Sons; 1998; p.179–199. [ Links ]

2. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Smith TS. Psychiatric rehabilitation. In: Sadock V, Sadock RJ (eds.). Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1999; p.3218–3245. [ Links ]

3. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Translating research into practice: The schizophrenia patient outcomes research team (PORT) treatment recommendations and client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1998;24:1–20. [ Links ]

4. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NB, Wu AH, Wilson MH et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? J Am Medical Assoc 1999;282:1458–1465. [ Links ]

5. Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, Bums BJ, Flynn L, et al. Implementing evidence–based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 2001;52:45–50. [ Links ]

6. United States Census Bureau. Profiles of general demographic characteristics: 2000 Census of Population and Housing, United States. Washington DC: 2001. [ Links ]

7. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity–a supplement to mental health: a report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: US. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [ Links ]

8. Lopez SR, Kopelowicz A, Cañive J. Strategies in developing culturally congruent family interventions for schizophrenia: The case of Hispanics. In: Family lnterventions in mental illness: international perspectives. Lefley HP, Johnson DL (eds.). Westport CT. London: Praeger; 2001; p.61–92. [ Links ]

9. Liberman RP, Mueser K, Wallace CJ, Jacobs HE, Eclanan T. Training skills in the psychiatrically disabled: Leaming coping and competence. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1986;2:631–647. [ Links ]

10. Liberman RP, Coitigan PW. Designing new psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. Psychiatry 1993;56:238–249. [ Links ]

11. Heinssen RK, Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A. Psychosocial skills training for schizophrenia: Lessons from the laboratory. Schizophrenia Bull 2000;26:21–46. [ Links ]

12. Kopelowicz A. Social skills training: The moderating influence of culture in the treatment of Latinos with schizophrenia. J Psychopathology Behavioral Assessment 1997;19:101–108. [ Links ]

13. Benton MK, Schroeder HE. Social skills training for schizophrenics: a meta–analysis evaluation. J Consulting Clinical Psychology 1990;58:741–747. [ Links ]

14. Dilk M, Bond GR. Meta–analytic evaluation of skills training research for individuals with severe mental illness. J Consulting Clinical Psychology 64:1337–1346,1996. [ Links ]

15. Halford WK, Hayes R. Psychological rehabilitation of chronic schizophrenic patients: Recent findings on social skills training and family psychoeducation. Clin Psychol Review 1991;23:23–44. [ Links ]

16. Bellack AS, Tumer SM, Hersen M, Luber RF. An examination of the efficacy of social skills training for chronic schizophrenic patients. Hospital Community Psychiatry 1984;35:1023–1028. [ Links ]

17. Penn DL, Mueser KT. Research update on the psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:607–617. [ Links ]

18. Guarnaccia PJ, Parra P. Ethnicity, social status, and families' experiences of caring for a mentally ill family member. Community Mental Health J 1996;32:243–260. [ Links ]

19. Karno M, Jenkins JR, Selva A, Santana F, Telles C et al. Expressed emotion and schizophrenia outcome among Mexican–American families. J Nervous Mental Disease 1987;175:143–151. [ Links ]

20. Jenkins JR, Karno M. The meaning of expressed emotion: Theoretical issues raised by cross–cultural research. Am Psychiatry 1992;149:9–21. [ Links ]

21. Guarnaccia P. Hispanic families experience in coping with serious mental disorder. Culture Medicine 1992;16:187–215. [ Links ]

22. Kopelowicz A, Zarate R, Gonzalez V, Lopez SR, Ortega P et al. Evaluation of expressed emotion in schizophrenia: A comparison of Caucasians and Mexican– Americans. Schizophrenia Research, in press. [ Links ]

23. Eckman TA, Liberman RP, Phipps C, Blair K. Teaching medication management skills to 30 schizophrenic patients. J Clinical Psychopharmacology 1990;10:33–38. [ Links ]

24. Eckman TA, Wirshing WC, Marder SR, Liberman RP, Johnston–Cronk K et al. Technique for training schizophrenic patients in illness self management: A controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:1549–1555. [ Links ]

25. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, Eckman TA, Vaccaro JV et al. Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: The VCLA Social & Independent Living Skills Modules. lnnovations Research 1993;2:43–60. [ Links ]

26. Marder SR, Wirshing WC, Mintz J, McKenzie J, Johnston K et al. Two year outcome of social skills training and group psychotherapy for outpatients with schizophrenia. American J Psychiatry 1996;153:1585–1592. [ Links ]

27. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinicali Interview for DSM–IV axis 1 disorders–patient edition (SCID–I/P, Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [ Links ]

28. D'Zurilla TJ. Problem–solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 1986. [ Links ]

29. Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, MacKain SJ, Blackwell G, Eckman TA. Effectiveness and replicability of modules for teaching social and instrumental skills to the severely mentally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:654–658. [ Links ]

30. Leslie LA, Leitch ML. A demographic profile of recent Central American immigrants: clinical and service implications. Hispanic J Behavioral Sciences 1989;11:315–329. [ Links ]

31. Lopez SR. Latinos and the expression of psychopathology: A call for the direct assessment of cultural influences. In: Telles C, Karno M (eds.). Latino mental health: current research and policy perspectives. Washington, DC: National Institute of MentaI Health; 1994. [ Links ]

32. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1987;13:261–276. [ Links ]

33. Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, Tauber R, Wallace J. The independent living skills survey: a comprehensive measure of the community functioning of severely and persistently mentally ill individuals. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2000;26:631–658. [ Links ]

34. Lehman AF, Ward NC, Linn LS. Chronic mental patients: The quality of life issues. American J Psychiatry 1982;134:1271–1276. [ Links ]

35. Weiden P, Rapkin B, Mott T, Zygmunt A, Goldman D et al. Rating of medication influences scale in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1994;20:297–310. [ Links ]

36. Liberman RP, Glynn SM, Marder SR, Blair K, Wirshing WC. In vivo amplified skills training for enhancing generalization of social skills training into everyday life. Psychiatry in press. [ Links ]

37. Miller JF, Powers MJ. Development of an instrument to measure hope. Nursing Research 1988;37:6–10. [ Links ]

38. Magaña AB, Goldstein MJ, Karno M, Miklowitz DJ, Jenkins J et al. A brief method for assessing expressed emotion in relatives of psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Research 1986;17:203–212. [ Links ]

39. Vaughn CE, Leff JP. The measurement of expressed emotion in the families of psychiatric patients. British J Psychiatry 1976;129:157–165. [ Links ]

40. Asamow JR, Goldstein MJ, Tompson M, Guthrie D. One–year outcomes of depressive disorders in child psychiatric in–patients: Evaluation of the prognostic power of a brief measure of expressed emotion. J Child Psychology Psychiatry Allied Disciplines 1993;34:129–137. [ Links ]

41. Pai S, Kapur RL. The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: Development of an interview schedule. British J Psychiatry 1981;138:332–335. [ Links ]

42. Liberman RP, Blair KE, Glynn SM, Marder SR, Wirshing WC. Generalization of skills training to the natural environment. In: Brenner HD (ed.). Boker W. Genner R (eds.). The treatment of schizophrenia: status and emerging trends. Seattle: Huber and Hogrefe; 2001; p.104–120. [ Links ]

43. Tauber R, Wallace CJ, Lecomte T. Enlisting indigenous cornmunity supporters in skills training programs for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 2000;51:1428–1432. [ Links ]

44. Glynn SM, Marder SR, Liberman RP, Blair K, Wirshing WC et al. Supplementing clinic based skills training for schizophrenia with manualized community support: Effects on social adjustment. Am J Psychiatry, in press. [ Links ]

45. Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP. Psychological and behavioral treatments for schizophrenia. In: Nathan PE, Gorman JM (eds.). Treatrnents that work. London: Oxford University Press; 1998; p.190–211. [ Links ]

46. Liberman RP, Nuechterlein KH, Wallace CJ. Social skills training and the nature of schizophrenia. In: Cuitan JP, Monti PM (eds.). Social skills training: a practical handbook for assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1982; p.5–56. [ Links ]

47. Liberman RP. Cognitive remediation of schizophrenia. In: Takashi K, Mizuno N (eds.). From neurobiology to psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia. Tokyo: Springer–Verlag; 2001. [ Links ]

48. Becker DR, Smith J, Tanzman B, Drake RE, Tremblay T. Fidelity of supported employment programs and employment outcomes. Psychiatric Services 2001;52:834–836. [ Links ]

49. Bond GR, Evans L, Salyers MP, Williams J. Measurement of fidelity in psychiatric rehabilitation. Mental Health Services Research 2000;2:75–87. [ Links ]

50. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Teague GB, Xie H. Fidelity to assertive community treatment and client outcomes in the New Hampshire dual disorders study. Psychiatric Services 1999;50:818–824. [ Links ]

51. Hosch HM, Barrientos GA, Fierro C, Ramirez JI, Pelaez MP et al. Predicting adherence to medications by Rispanics with schizophrenia. Hispanic J Behavioral Sciences 1995;17:320–333. [ Links ]

52. Wirshing WC, Marder SR, Eckman TA, Liberman RP, Mintz J. Acquisition and retention of self–management skills in chronic schizophrenic outpatients. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 1992;28:241–245. [ Links ]

53. Lam JA, Rosenheck RA. Correlates of improvement in quality of life among homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 2000;51:116–118. [ Links ]

54. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: Empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1997;23:637–651. [ Links ]

55. Jenkins JR, Kamo M, De la Selva A, Santana F. Expressed emotion in cross–cultural context: Familial responses to schizophrenic illness among Mexican–Americans. In: Goldstein MJ, Rand I., Rahlweg K (eds.). Treatment of schizophrenia: Family assessment and intervention. Berlin: Springer–Verlag; 1992; p. 35–49. [ Links ]

56. Liberman RP. Handbook of pychiatric rehabilitation. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1992. [ Links ]

*Conferencia Magistral dictada el 4 de septiembre de 2008 dentro de la XXIII Reunión Anual de Investigación del INPRF.