Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Contaduría y administración

versión impresa ISSN 0186-1042

Contad. Adm vol.68 no.2 Ciudad de México abr./jun. 2023 Epub 02-Dic-2024

https://doi.org/10.22201/fca.24488410e.2023.2997

Articles

Analysis of factors affecting the intention and transfer of knowledge within organizations among employees in the automotive industry on the northern border of Mexico

1Tecnológico Nacional de México, México

2Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, México

3Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla, México

The objective of this research is to analyze if affective commitment, relational psychological contract, attitude and subjective norm affect the intention to share tacit knowledge and the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge. A quantitative, non-probabilistic, explanatory, cross-sectional and nonexperimental study was conducted. A total of 346 questionnaires were applied to employees of the automotive industry in the northern border of Mexico. The statistical analysis was performed using structural equations based on partial least squares (PLS). Findings indicate that affective commitment is not related to intention to share tacit knowledge, but it is related to the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge. Furthermore, the relational psychological contract, attitude and subjective norm, positively impact the intention to share tacit knowledge and this last positively affects the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge. These findings contribute to academic knowledge, since in Mexico the constructs have only been addressed independently.

Keywords: affective commitment; relational psychological contract; intention to share tacit knowledge; organizational transfer; northern border of Mexico

JEL Code: M10; M12; M19

El objetivo de la presente investigación es analizar si el compromiso afectivo, el contrato psicológico relacional, la actitud y la norma subjetiva afectan la intención de compartir conocimiento tácito y la transferencia interna organizacional de conocimiento tácito. Se realizó un estudio cuantitativo, no probabilístico, explicativo, transversal y no experimental. Se aplicaron 346 cuestionarios a colaboradores de la industria automotriz en la frontera norte de México. El análisis estadístico fue mediante ecuaciones estructurales basado en mínimos cuadrados parciales (PLS). Los resultados indican que el compromiso afectivo no está relacionado con la intención de compartir conocimiento tácito, pero sí con la transferencia interna organizacional de conocimiento tácito. Asimismo, el contrato psicológico relacional, la actitud y la norma subjetiva impactan favorablemente la intención de compartir conocimiento tácito y esta última incide positivamente sobre la transferencia interna organizacional de conocimiento tácito. Estos hallazgos abonan al conocimiento académico, ya que en México los constructos solo han sido abordados en forma independiente.

Palabras clave: compromiso afectivo; contrato psicológico relacional; intención de compartir conocimiento tácito; transferencia organizacional; frontera norte de México

Código JEL: M10; M12; M19

Introduction

Developing and exploiting employee knowledge has become increasingly important for organizations, particularly for tacit knowledge since it is considered an intangible asset of great value for the strategic support and development of organizational activities. Hence, it is important to review how human resources and their knowledge are managed (Guerrero, 2016).

When tacit knowledge is shared, new knowledge is generated and then preserved, developed, exploited, and transferred within the company to achieve organizational success (Arellano, 2015) since it is the key element for making decisions that guide the organization’s management. When this happens, it generates advantages in the development of skills and competencies; it increases the value of the company, fosters innovation, and, above all, generates sustainable competitive advantages (Máynez, 2011; Loebbecke, Fenema, & Powell, 2016; Tangaraja, Rasdi, Samah, & Ismail, 2016). Therefore, the difference in the accumulation of knowledge of organizations may be leveraged in conjunction with the skills of its staff in the right place at the right time (Arellano, 2015; Máynez, 2016). Nevertheless, several factors are involved for tacit knowledge to be shared and transferred to different organizational levels, among which personal aspects such as the subject’s commitment to the company and the relational or behavioral psychological contract stand out. This is because, according to Ajzen and Fishbein’s Theory of Reasoned Action (1972), the subject’s intention to perform a certain action must be evaluated through the observation of both attitudinal and normative beliefs because they directly influence their behavior at the moment of making personal decisions in a given situation (Flores-Alarcón, 2018). Thus, the present research aimed to analyze whether affective commitment, the relational psychological contract, attitude, and subjective norms affect the intention to share tacit knowledge and the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge in collaborators of the automotive industry on the northern border of Mexico.

This paper is divided into four sections: the first section reviews the literature to analyze the different ways in which the variables studied have been evaluated and to support the hypotheses put forward; the methodology used and the analysis of the results obtained are presented; and finally, the discussion and conclusions of the study are presented.

Literature review and development of hypotheses

Since its establishment in the 1960s, when the “Bracero Program” was terminated, the manufacturing industry has been considered the main source of employment in Ciudad Juarez (Villalpando, 2004). At that time, intending to employ the displaced people from that program, the Mexican government made an effort and created the National Border Program (PRONAF; Spanish: Programa Nacional Fronterizo) to promote economic and social development in Mexico’s borders. This led to the arrival of foreign companies, which created jobs and strengthened the city’s economy (Carrillo & Hualde, 1996; Villalpando, 2004; Contreras & Munguía, 2007). In 1998, the decree for formalizing manufacturing industry operations in Mexico was issued (Diario Oficial de la Federación, 1998).

Today, the context of the manufacturing industry has changed. Production and administrative processes have evolved, and they have state-of-the-art technology for the development and specialized training of their personnel (Carrillo & Ramírez, 1990). Nonetheless, to be successful in their operations, the active participation of their members is required since it is they who create the tacit knowledge that accumulates over time, and to take advantage of it, it is necessary to share it since this intangible asset is a source of irreplaceable competitive advantages (Contreras & Hualde, 2004). Academics Nonaka and Takeuchi (1999) stated that middle management in companies acts as an intermediary bridge between senior management and operational employees, and it is at this point where knowledge flows to different organizational levels (Shuang-Shii, Kun-Shiang, & Ming-Tien, 2015).

The economic development of Mexico’s northern border remains a strategic point for the manufacturing industry, thanks to its geographic location and optimization of freight delivery times, which allows companies to reduce logistics times and tariffs in their operations, among other advantages. According to the National Institute of Statistics, Geography, and Informatics (INEGI; Spanish: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática), as of November 2021, 322 organizations in Juarez were active under the Manufacturing and Export Services Industry scheme, which represents 6.23% of the national economy and 66% at the state level (INEGI, 2022). Of these companies, 39 are in the automotive sector, including Lear Corporation (11 facilities), Aptiv (12 facilities), and Robert Bosch (3 facilities), which are located in the city’s various industrial parks and zones (IMIP, 2021). Furthermore, according to the latest monthly employment statistics provided by the Maquiladora Association, A.C. (INDEX)-an organization that brings together the industrial sector on this border-as of the end of October 2022, Chihuahua generated 515 870 jobs (17.5% of the national total) and Cd. Juárez 341 715 (12% of the national total and 6.40% at the local level) in this production sector (INDEX, 2022).

Intention to share knowledge

In the organizational environment, knowledge is a strategic ingredient, and taking advantage of it will depend to a large extent on managing it. It represents a combination of values, experiences, and skills, which serve as a basis for the generation of new knowledge, its improvement, or a modification of previous knowledge (Li, Zhang, & Zhou, 2017). The most viable option to avoid the risk of losing it is to share it, since in this way, not only can organizational results be achieved, but also the perceived individual benefits of those who share it as an act of reciprocity (Chang-Wook, Hea & Myungweon, 2017; Martin-Perez & Martin-Cruz, 2015). Sharing knowledge involves two actors: on the one hand, the one who shares it (sender), and on the other hand, the one who receives it (receiver). This act is expected to be voluntary since, according to Castañeda (2015), it does not arise spontaneously because it depends largely on human variables that must be analyzed.

According to Ming-Tien, Kun-Shiang, and Jui-Lin (2012), intention is the subject’s willingness or desire to contribute to something or someone, as long as it is in a positive way, voluntarily, and unconditionally, since sharing knowledge is an act of reciprocity and the organization cannot impose any internal control on employees to share their knowledge with others. Nevertheless, to arouse this intention to participate, it is necessary to assess the subject’s behavior, because intention is the most obvious indication of the subject’s willingness to manifest a certain collaborative behavior (Fauzi, Ling Tan, Thurasamy & Ojo, 2019; Punniyamoorthy & Asumptha, 2019).

Psychological contract

The psychological contract is a process of exchanging mutual expectations between the employee and the organization, where both expect common benefits (Zhike & Ting, 2018). The psychological contract can be studied through the transactional and relational psychological contracts. The latter is established indefinitely, usually long-term (Rousseau, 1989). It is characterized by being emotional and subjective because loyalty and trust prevail between the parties involved (Martinez, 2018), and both the employee and the organization are committed to contributing to achieving mutual goals (Adamska, Jurek & Rózicka-Tran, 2015). The relational psychological contract plays a very important role when talking about organizational results since its study focuses on the beliefs and work expectations of individuals (Vesga, 2011), which are usually not manifested but can affect the perception of the subject and experience poor job performance and commitment to the organization (Rousseau, 1989). In addition, the subject’s beliefs are implicit in their behavior when deciding to contribute to the organization and share their knowledge since these and related social relationships are connected to work and based on day-to-day experiences (Adamska et al., 2015). Likewise, the type of attachment that the subject has to the organization is an individual factor that determines how they perceive the events that happen around them and allow them to decide how they will participate by awakening in them the intention to share their knowledge (Schmidt, 2016) as well as the willingness to work in a team and adapt to change (García & Forero, 2018).

Alternatively, during the term of the employment relationship, situations of various kinds may occur, and the psychological contract may be violated, or agreements may not be fulfilled. This condition is detrimental to both parties, especially for employees, as they may experience a sense of failure and develop a negative attitude, which will consequently be reflected in low satisfaction and productivity and in their organizational commitment (Rousseau, 1989; García & Forero, 2018). Hence, the organization must comply with the agreements and promises agreed in the psychological contract so that the employee feels committed to their work and collaboration is mutual for the benefit of both parties (Zhike & Ting, 2018).

The relational psychological contract has been addressed and related to several variables, such as job satisfaction (Millward & Hopkins, 1998), work stress (García & Forero, 2018), noncompliance, performance, and organizational commitment (Zhike & Ting, 2018; Rousseau, 1989; Guerrero, 2016), among others. There is empirical evidence that the relational psychological contract is closely linked to the subject’s intention in their desire to contribute, since when the employee feels comfortable and satisfied with their work relationship, they have a greater willingness to contribute and provide their support to the organization once their intention to share their knowledge with their coworkers is triggered (Day & Wang, 2016). Based on the above, it is proposed that:

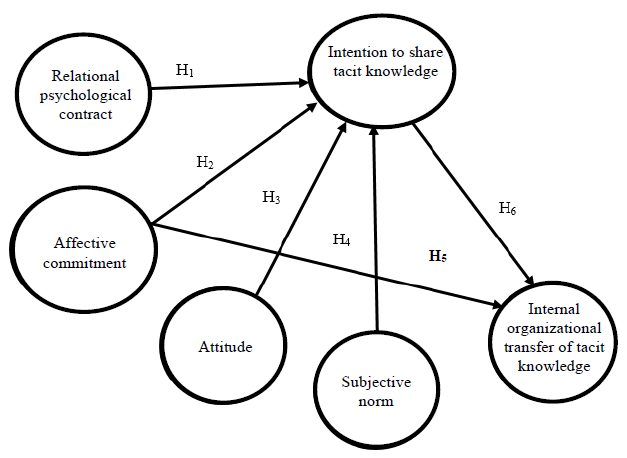

H1.- The relational psychological contract is positively and significantly related to the intention to share tacit knowledge.

Affective commitment

In the organizational environment, several variables are associated with the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge; among them is the individual’s affective commitment. Organizational commitment is recognized as an important component in understanding people’s work behavior and is studied in three dimensions: normative commitment, continuance commitment, and affective commitment. According to Meyer, Allen, and Smith (1993), affective commitment is characterized as an employee’s strong attachment to the company’s objectives and values, which generates a great sense of pride in being part of it and the decision to stay there by choice (Loli, Montgomery, Cerón, Carpio, Navarro, & Llacho, 2015; Sadiya & Maimunah, 2016). Mercurio (2015) conceives it as the essence of organizational commitment because it stands as the most important indicator of organizational results. Affective commitment works as a reducer of uncertainty and decreases the intention of abandonment. If the company induces high levels of affective commitment among its staff, positive benefits can also be achieved in the subject’s loyalty (Martin-Perez & Martin-Cruz, 2015).

The effect of affective commitment has also been analyzed in both young and not-so-young generations, and the results are similar. This confirms that the subject tends to be more motivated and enthusiastic about their work in an environment with high levels of affective commitment (Li et al., 2017). Together with the relationship with the leader, it allows them to develop a positive attitude, better interrelationships with their colleagues, and consequently, contribute to their desire and willingness to collaborate with the organization and coworkers (Mitonga-Monga, Flotman & Cilliers, 2018; Chang-Wook et al., 2017; Faraz & Lenka, 2017; Sadiya & Maimunah, 2016; Martin-Perez & Martin-Cruz, 2015).

Affective commitment has been widely studied in different settings and contexts and in relation to several variables, notably job satisfaction (Mitonga-Monga et al., 2018; Lizote, Verdinelli, & do Nascimento, 2017), job performance (Kaplan & Kaplan, 2018; Chang, Leach, & Anderman, 2015), socialization (Calderón, Laca, Pando, & Pedroza, 2015), personality traits (Izzati, Suhariadi, & Hadi, 2015; Emecheta, Hart, & Ojiabo, 2016), perceived organizational support, work experience, trust (Gupta, Agarwal, & Khatri, 2016; Mercurio, 2015), and knowledge transfer within the organization (Máynez, 2016).

In addition, affective commitment arises from organizational knowledge. Evidence suggests that, both at group and individual levels, knowledge can be shared when there are high levels of affective commitment (Chang-Wook et al., 2017) as it is closely related to the subject’s intention and behavior in their desire to participate when they perceive that the organization values their contribution and well-being (Máynez, Cavazos, Ibarreche, & Nuño de la Parra, 2012; Faraz & Lenka, 2017; Contreras-Pacheco, 2018; Curtis & Taylor, 2018). Based on the above, it is proposed that:

H2.- Affective commitment is positively and significantly related to the intention to share tacit knowledge.

On the other hand, Ajzen and Fishbein’s (1972) Theory of Reasoned Action has been widely used in different disciplines to predict human behavior. According to this, to awaken the subject’s intention to perform a certain action, both attitudinal and normative beliefs should be evaluated because they directly influence their behavior when making personal decisions in the face of a given situation (Flores-Alarcón, 2018).

Attitude is characterized by the subject’s feelings of liking or disliking when manifesting certain behavior to perform a certain action (Bock, Zmud, Kim, & Lee, 2005) so that they evaluate to decide whether it is convenient or not to act based on the perception of their actions, consequences, and values (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1972). Moreover, the subjective norm is manifested through the social pressure that the subject experiences when they receive comments or suggestions from people they consider important, which they evaluate in conjunction with the power they exert over them, and coupled with their level of motivation, will allow them to react and manifest a certain behavior when deciding on a certain situation that is presented to them (Shin-Yuan, Hui-Min, & Yu-Che, 2015; Punniyamoorthy & Asumptha, 2019). In this study, to determine the degree of willingness and participation that the employee has toward the organization and their coworkers, both the attitude and the subjective norm were analyzed as antecedents of the intention to share knowledge, adopting the Theory of Reasoned Action in its evaluation. In terms of attitude, the collaborator analyzes whether or not it is convenient for them to share their tacit knowledge with other coworkers once they assess the factors that have influenced them to acquire the knowledge they possess (Shuang-Shii, Kun-Siang, & Ming-Tien, 2015). As for the subjective norm, the collaborator responds to social pressures by assessing whether it is important to heed or ignore the comments or suggestions issued by their superiors or coworkers, and depending on their level of motivation at that moment, they will manifest a certain behavior based on whether or not they desire to share their tacit knowledge (Young, Byoungsoo, & Heeseok, 2016; Smith, 2017).

Furthermore, Asrar-ul-Haq and Anwar (2016) note that in order to share knowledge, it is not enough to have the intention to do so, as the subjective norm can be induced by factors that can facilitate or impede knowledge sharing and transfer, such as trust and organizational culture, as well as by the reward and motivation system implemented by organizations. Other studies suggest that when people have good social interrelationships with their coworkers and a positive perception of the ethics of their superiors, they develop a more favorable attitude (Bock et al., 2005), thus confirming that both attitude and subjective norm are closely related to the subject’s intention to share their knowledge (Woolley, 2015; Razmerita, Kirchner, & Nielsen, 2016; Fauzi et al., 2019). Based on the above, it is proposed that:

H3.- Attitude is positively and significantly related to the intention to share tacit knowledge.

H4.- The subjective norm is positively and significantly related to the intention to share tacit knowledge.

Internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge

In knowledge management, two types of organizational knowledge can be differentiated according to their structuring and codification: tacit and explicit. Tacit knowledge lies in the subject’s subjectivity, ideas, and hunches. It is highly personal because it is rooted in the individual’s experience, making it difficult to express in words and limiting its scope and dissemination; its dissemination can be costly since it is only shared through direct contact with people, i.e., face to face (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1999; Máynez, 2011). Due to the nature and importance of this type of knowledge, it is necessary to share it with other people so that it can be transferred to different organizational levels and thus be used for the benefit of all company members.

To ensure that the transfer of tacit knowledge within the organization is successful, Nonaka and Takeuchi (1999) suggest transforming it into different forms of communication so that all members understand it and the organization is also involved in the transfer (Argote & Fahrenkopf, 2016). When this happens, changes in organizational practices and policies are triggered because the new knowledge lies in the structure, rules, procedures, strategies, and technologies (Shin-Yuan et al., 2015; Loebbecke et al., 2016; Máynez & Noriega, 2015). Consequently, the organization becomes an entity capable of transforming itself and achieving respect among its members since by applying this new knowledge in the development of the tasks and activities of its collaborators, it improves work performance, productivity, and the generation of ideas and concepts that contribute to innovation and the development of sustainable competitive advantages (Loebbecke et al., 2016; Máynez, 2011).

Furthermore, for knowledge transfer to take place, the participation of both the employee and the organization is necessary, and several factors influence it, among them intention and affective commitment. On the one hand, the subject’s intention to share their knowledge is supported by their willingness to do so and their expectation of reciprocity from the company (Máynez et al., 2012; Máynez, 2016). On the other hand, when the employee has a high level of commitment (Chang-Wook et al., 2017), knowledge transfer within the company can be successful since affective commitment acts as a facilitator in this process (Sadiya & Maimunah, 2016; Faraz & Lenka, 2017; Mitonga-Monga et al., 2018). Based on the above, it is proposed that:

H5.- Affective commitment is positively and significantly related to the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge.

H6.- The intention to share tacit knowledge is positively and significantly related to the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge.

The basic research model is shown below in Figure 1.

Method

Sample and data collection

A quantitative, non-probabilistic, explanatory, cross-sectional, and non-experimental study was conducted. A questionnaire was used for data collection, adapted, and answered by middle management collaborators, whose main function is implementing coordination strategies, managing assigned resources, and supervising the processes in their area. These personnel also maintain close communication with other personnel to achieve organizational goals and objectives in two ways: internally with operational personnel in their area and with collaborators from other departments, and externally with suppliers and clients. The sample comprised engineers, supervisors, analysts, and technicians from the morning and afternoon shifts, working in several companies in the export manufacturing industry, specifically in the automotive sector in the northern border of Mexico. The fieldwork was carried out from August to October 2016, and in total, 346 questionnaires were collected with 33 valid items for analysis, of which 273 were male (78.9%), 72 were female (20.8%), and one person did not indicate their gender (0.3%). Of these, 54.9% reported being between 20 and 30 years of age. The majority reported being single (48.6%). 64.6% had a bachelor’s degree, and 46.5% held a technical position, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of participants

| Respondents | Percentage | ||

| Gender | Male | 273 | 78.9 |

| Female | 72 | 20.8 | |

| Not Answered | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Age | Between 20 and 30 years old | 190 | 54.9 |

| Between 31 and 40 years old | 94 | 27.2 | |

| Between 41 and 50 years old | 51 | 14.7 | |

| Between 51 and 60 years old | 9 | 2.6 | |

| Not Answered | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Schooling | Secondary | 12 | 3.5 |

| Baccalaureate | 66 | 19.1 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 224 | 64.6 | |

| Master’s Degree | 34 | 9.8 | |

| PhD | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Not Answered | 9 | 2.6 | |

| Position | Engineer | 116 | 33.5 |

| Supervisor | 48 | 13.9 | |

| Analyst | 21 | 6.1 | |

| Technician | 161 | 46.5 |

Source: created by the authors

Assessment of the constructs

A questionnaire was used to assess the variables under study, the process of which consisted of four stages: (a) a literature review was made to learn about the various ways in which the variables had been evaluated; (b) the instrument was selected, translated (where necessary) and adapted to the cultural context; (c) the first version of the questionnaire was made and submitted for consideration to a group of experts to achieve a better understanding of the items formulated; and (d) according to the comments and suggestions of the experts, the pertinent corrections were made and the final version was formulated. The questionnaire items were designed with statements evaluated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1, “totally disagree,” to 5, “totally agree.” To measure the variables under study, 8 items were adapted from the Psychological Contract Scale (PCS) developed by Millward and Hopkins (1998) to assess the relational psychological contract. 6 items were adapted from the Three-Component Model (TCM) developed by Meyer et al. (1993) to assess affective commitment. 5 items were adapted based on Bock et al. (2005) and Máynez (2011) to assess intention to share tacit knowledge. 4 items were adapted to assess the subjective norm and 3 items to assess attitude, both based on Bock et al. (2005). Finally, 7 items were used based on Máynez (2011) to assess the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge. The statistical analysis of the data was performed by structural equation modeling (SEM) based on partial least squares (PLS) using Smart PLS3 software (Ringle, Wende, & Becker, 2015).

Analysis of results

Model assessment

The reliability of the indicators was assessed and verified, as well as the reliability of the internal consistency of the constructs, as shown in Table 2. Regarding the reliability of both the indicators and the internal consistency of the constructs, Bagozzi and Yi (1988) recommend that the cut-off point should preferably reach a value of 0.70 or higher. Nevertheless, concerning the indicators, Chin (1988) suggests that indicators with loadings lower than 0.70 can be retained if there are indicators in the construct with loadings higher than the indicated value. Consequently, and following the recommendations of the experts, this condition was met in the assessment of the model, as the loadings were higher than 0.70 for most of the indicators, except for two items corresponding to the construct relational psychological contract (cpr1 and cpr8), one item belonging to the construct intention to share tacit knowledge (ic18), and one item of the construct subjective norm (ns23), which did not exceed the cut-off point. Nonetheless, following Chin’s (1988) criteria, the indicators were retained as most of the indicators of the constructs had loadings above 0.70. The internal consistency reliability of the constructs was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability as suggested by Bagozzi and Yi (1988) to corroborate it, obtaining scores above 0.70 for both criteria. Likewise, the convergence validity of the constructs was assessed through the average analysis of variance extracted (AVE) to measure the degree to which the indicators of a construct share a portion of variance among them-with the recommendation that the value reached be 0.50 or higher, according to the experts (Chin, 1988; Bagozzi, and Yi, 1988)-fully complying with these criteria in the research model. The above is shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Internal consistency validity of the indicators and convergent validity of the constructs

| Latent variable | Indicators | Loads | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite reliability | AVE |

| Relational

psychological contract |

cpr1 | 0.61 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.50 |

| cpr2 | 0.72 | ||||

| cpr3 | 0.76 | ||||

| cpr4 | 0.75 | ||||

| cpr5 | 0.70 | ||||

| cpr6 | 0.75 | ||||

| cpr7 | 0.72 | ||||

| cpr8 | 0.64 | ||||

| Affective commitment | ca9 | 0.76 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.65 |

| ca10 | 0.77 | ||||

| ca11 | 0.84 | ||||

| ca12 | 0.88 | ||||

| ca13 | 0.87 | ||||

| ca14 | 0.71 | ||||

| Intention to share tacit

knowledge |

ic15 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.64 |

| ic16 | 0.88 | ||||

| ic17 | 0.86 | ||||

| ic18 | 0.64 | ||||

| ic19 | 0.76 | ||||

| Subjective norm | ns20 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.59 |

| ns21 | 0.86 | ||||

| ns22 | 0.83 | ||||

| ns23 | 0.54 | ||||

| Attitude | act24 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.78 |

| act25 | 0.91 | ||||

| act26 | 0.86 | ||||

| Organizational internal

transfer of tacit knowledge |

tc27 | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.67 |

| tc28 | 0.76 | ||||

| tc29 | 0.83 | ||||

| tc30 | 0.87 | ||||

| tc31 | 0.79 | ||||

| tc32 | 0.84 | ||||

| tc33 | 0.82 |

Source: created by the authors based on SMART PLS results

The discriminant validity of the model was also assessed to analyze the relation between the latent variables and the extent to which an indicator represents only the construct to which it corresponds. In this regard, Fornell-Larcker (1981) indicates that the square root of the average analysis of variance extracted (AVE) of each construct should be greater than the correlation levels of the construct to verify that the variables really measure what they are supposed to measure. An alternative tool used to corroborate that the indicators corresponding to each construct are measuring only that construct is the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT), which indicates that the values obtained should preferably be less than 0.85 to ensure that there is a solid discriminant validity between the constructs (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015). Table 3 shows the values obtained in both criteria, where the square root of the AVE can be seen above the diagonal and the corresponding correlations below the diagonal. In all cases, the values obtained are below 0.85, thus corroborating the discriminant validity of the model.

Table 3 Discriminant validity of the model

| Fornell-Larcker Criterion | Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio Criterion | ||||||||||

| act | ca | cpr | Ic | Ns | tc | act | ca | cpr | ic | ns | |

| Attitude (act) | 0.88 | ||||||||||

| Affective commitment (ca) | 0.36 | 0.81 | 0.41 | ||||||||

| Psychological relational contract (cpr) | 0.41 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.47 | 0.73 | ||||||

| Intention to share tacit knowledge (ic) | 0.70 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.40 | 0.54 | ||||

| Subjective norm (ns) | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.64 | ||

| Internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge (tc) | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.63 |

Source: created by the authors based on SMART PLS results

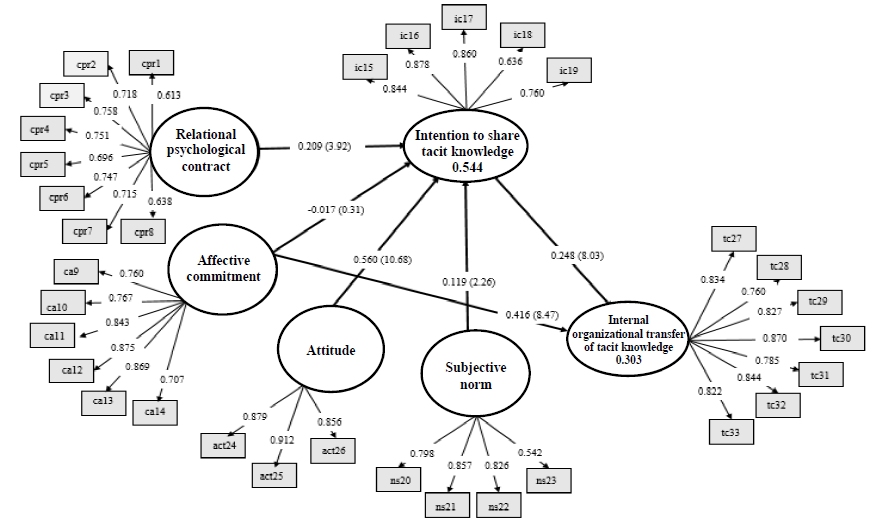

The structural model, shown in Figure 2, presents the factor loadings obtained for each of the observable variables and the path values of the structural relations. The relation of the relational psychological contract with the intention to share tacit knowledge was 0.209, of the affective commitment with the intention to share tacit knowledge was -0.017, of the attitude with the intention to share tacit knowledge was 0.560, of the subjective norm with the intention to share tacit knowledge was 0.119, of intention to share tacit knowledge with organizational internal transfer of tacit knowledge was 0.248, and of affective commitment with organizational internal transfer of tacit knowledge was 0.416.

Regarding the prediction of the structural model, the coefficient of determination (R2) obtained for the intention to share tacit knowledge construct was 0.544. That is, the latent variables relational psychological contract, affective commitment, subjective norm, and attitude explain more than 50% of the variance of this construct. Regarding the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge, the coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.303, so affective commitment and intention to share tacit knowledge together explain 30.3% of the variance of this construct.

On the other hand, regarding the hypotheses proposed, the values obtained at a reliability level of 95% were: H1, t=3.92; H2, t=0.31; H3, t=10.68; H4, t=2.26; H5, t=8.47; and H6, t=8.03. Therefore, the hypotheses proposed in the present study are not rejected except for H2, where it was stated “H2. - Affective commitment is positively and significantly related to the intention to share tacit knowledge,” as a statistically non-significant association with the intention to share tacit knowledge (-0.017) was obtained. Nevertheless, it maintains a positive effect on the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge (0.416), confirming the association between the other constructs.

Discussion

Due to the constant global changes that organizations face daily to compete and maintain relevance, their main support lies in one of their most valuable resources: organizational knowledge. An efficient strategy to take advantage of it is to share it and adapt it to the circumstances through the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1999, p.7). Therefore, the present study aimed to analyze whether affective commitment, relational psychological contract, attitude, and subjective norms affect the subject’s intention to share their tacit knowledge and the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge in collaborators of the automotive industry in the northern border of Mexico.

The variables under study are important predictors of organizational success, but in Mexico, no studies address these constructs as a whole, as they have only been analyzed independently. Therefore, the findings of this research represent a contribution that helps to advance academic knowledge.

Regarding the influence of the relational psychological contract with the intention to share tacit knowledge, the evidence obtained confirms this relation. The results are consistent with the findings presented by Dai and Wang (2016) and corroborate what has been pointed out in previous works by indicating that subjects respond and behave with mutual reciprocity when they perceive that the company recognizes their efforts in the performance of their work to achieve common goals (Gupta, Agarwal, Samaria, Sarda & Bushab, 2012; Hung-Wen & Ching-Hsiang, 2009; Ming-Tien et al., 2012; Fantinato & Casado, 2011). In the context analyzed, the relational psychological contract was reflected in the fostering of teamwork, trust, mutual support, and recognition of the work by the company, indicating that employees feel satisfied with the support provided by the organization and that they contribute by sharing their tacit knowledge with other coworkers.

Regarding the effects of affective commitment, the evidence from this study shows both significant and non-significant results. On the one hand, the literature indicates that affective commitment acts as a facilitator in the subject’s behavior to collaborate for the benefit of the organization when there are high levels of commitment in the work environment (Mitonga-Monga et al., 2018; Chang-Wook, Hea, & Myungweon, 2017; Faraz & Lenka, 2017; Sadiya & Maimunah, 2016; Martín-Pérez & Martín-Cruz, 2015; Li et al., 2017). This approach is corroborated by some studies conducted whose results indicate that indeed affective commitment and intention to share knowledge have a positive association (Contreras-Pacheco, 2018; Curtis & Taylor, 2018; Chang-Wook et al., 2017; Faraz & Lenka, 2017; Máynez et al., 2012). Nonetheless, in the present study, affective commitment had a non-significant effect on the intention to share tacit knowledge. On the other hand, affective commitment has a direct, positive, and significant impact on the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge, corroborating the results of Máynez et al. (2012). Another study analyzed the relation between these variables in middle and upper management workers in the automotive, cement, medical, electronics, and telecommunications sectors in manufacturing companies in Chihuahua and Juárez, highlighting that affective commitment does not influence the internal transfer of knowledge (Máynez, 2016). In the perspective of the context analyzed, the fact that the collaborator has a high level of affective commitment to the organization does not mean that they have the intention or desire to share their tacit knowledge with coworkers; consequently, it is interesting to inquire further in this regard to learn more about the factors implicit in this. However, the employee’s affective commitment certainly influences the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge, which may indicate that the employee has an ingrained sense of belonging and is committed to collaborating on behalf of the organization to achieve its objectives.

Regarding the subject’s intention to share tacit knowledge, it was necessary to analyze the subject’s attitude and subjective norm, adopting for this purpose the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1972). The evidence from this study confirms that both attitude and subjective norm are closely related to the subject’s intention to share their tacit knowledge, with these findings confirming those obtained by Yong et al. (2016) and corroborating the approach of other researchers who suggest that when the subject is motivated and the recommendations and suggestions of their superiors to perform a certain action are appropriate, it is the right time to awaken their intention to share their tacit knowledge with other coworkers (Bock et al., 2005; Ming-Tien et al., 2012; Wu, 2013; Smith, 2017). Nonetheless, other studies were also found whose results indicate that subjective norms are not related to the intention to share knowledge (Fauzi et al., 2019; Shuang-Shii et al., 2015). In the automotive context of the northern Mexican border, the collaborator views sharing their tacit knowledge with other coworkers as an act of personal satisfaction and their own free will, without caring about the perceived social pressures or economic reward they could obtain, but rather they do it because they want to participate and contribute on behalf of the company.

Finally, regarding the influence of the subject’s intention to share tacit knowledge with the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge, the evidence obtained in the present study confirms this relation. The results are consistent with those of other works (Máynez et al., 2012; Castañeda, 2015) and are corroborated by the hypothesis that when knowledge is shared with other coworkers, the knowledge flows within the organization through several people and does not remain at the individual level. In the context analyzed, the intention and desire of the collaborator to share their tacit knowledge with other coworkers was reflected in the reciprocal participation of both the sender of the knowledge and the receiver, resulting in efficiency in performing activities, the creation of new ideas and work practices, and the sharing of ideas, knowledge, and skills among coworkers.

Conclusions

In the field of knowledge management, knowledge emerges from different sources. It must be correctly combined and directed by the organization for its benefit since the use of both personnel skills and organizational knowledge will depend to a great extent on the best practices, strategies, and methods implemented to face future challenges. This paper demonstrates that the variables studied strongly affect organizational success in automotive companies on Mexico’s northern border. An organization can nurture the sense of belonging of its collaborators so that they identify with it and thus strengthen their affective commitment, in addition to promoting effective communication channels that allow socialization and generation of trust among its members.

This work’s empirical evidence indicates no correlation between affective commitment and the employee’s intention to share their tacit knowledge. In the context studied, other factors may prevent the employee’s intention to do so, even if their affective work commitment is present. Nevertheless, affective commitment does have a positive impact on the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge. In the context analyzed, the employee knows and recognizes the importance of sharing organizational knowledge among all coworkers, which facilitates the performance of the company’s daily tasks.

Furthermore, empirical evidence indicates that the relational psychological contract positively influences the employee’s intention to share their tacit knowledge. In this type of organization, the employee feels satisfied with their expectations because they perceive reciprocity and compliance with the promises and agreements made with the company, which results in their desire to collaborate in achieving mutual objectives. Likewise, it has been demonstrated that the attitude and subjective norms of the collaborator contribute positively to their intention to share their tacit knowledge. In this industry, companies manage to trigger the employee’s intention to share their tacit knowledge, mainly through social interrelationships, since these have a stronger influence on the employee than the suggestions for participation received from their superiors. Therefore, both the relational psychological contract and the attitude and subjective norm explain their intention to share tacit knowledge by developing a positive collaborative attitude, which in turn positively impacts the internal organizational transfer of tacit knowledge. In this type of organization, tacit knowledge does not remain at a personal level but flows in different directions within the company because both the theory and the practice of internal and external guidelines of organizational knowledge are implicit, and this process facilitates the organization’s success in carrying out its operations.

Like any other work, this research has limitations, which reside mainly in the context analyzed since the findings obtained are exclusively from the automotive sector in the northern border area of Mexico and may differ from other contexts and populations, so they should be approached cautiously. The recommendation is to replicate this study in other contexts to compare results and analyze their behavior.

REFERENCES

Adamska, K., Jurek, P. y Rózycka-Tran, J. (2015). The mediational role of relational psychological contract in belief in a zero-sum game and work input attitude dependency. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 46(4), 579-586. https://doi.org/10.1515/ppb-2015-0064 [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. y Fishbein, M. (1972). Attitudes and normative beliefs as factors influencing behavioral intentions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031930 [ Links ]

Arellano Morales, M. F. (2015). Gestión del conocimiento como estrategia para lograr ventajas competitivas en las organizaciones petroleras. Revista Científica Electrónica de Ciencias Humanas 10(30), 31-47. [ Links ]

Argote, L. y Fahrenkopf, E. (2016). Knowledge transfer in organizations: The roles of members, tasks, tools, and networks. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 136(2), 146-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.08.003 [ Links ]

Asrar-ul-Haq, M. y Anwar, S. (2016). A systematic review of knowledge management and knowledge sharing: Trends, issues and challenges. Cogent Business and Management, 3(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2015.1127744 [ Links ]

Bagozzi, R. y Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equations models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74-94. [ Links ]

Bock, G.-W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y.-G. y Lee, J.-N. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social psychological forces, and organizational climate. Mis Quarterly, 29(1), 87-111. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148669 [ Links ]

Calderón Mafud, J. L., Laca Arocena, F. A., Pando Moreno, M. y Pedroza Cabrera, F. J. (2015). Relación de la socialización organizacional y el compromiso organizacional en trabajadores mexicanos. Psicogente, 18(34), 267-277. https://doi.org/10.17081/psico.18.34.503 [ Links ]

Carrillo, J. y Hualde, A. (1996). Maquilas de tercera generación. El caso de Delphi-General Motors. Espacios, 17(3), 1-8. [ Links ]

Carrillo Viveros, J. y Ramírez, M. A. (1990). Modernización tecnológica y cambios organizacionales en la industria maquiladora. Estudios Fronterizos, (23), 55-76. [ Links ]

Castañeda, Z. D. (2015). Knowledge sharing: the role of psychological variables in leaders and collaborators. Suma Psicológica, 22(1), 63-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sumpsi.2015.05.008 [ Links ]

Contreras, O. F. y Munguía, L. F. (2007). Evolución de las maquiladoras en México. Política industrial y aprendizaje tecnológico. Región y Sociedad, 19(especial). 71-87. https://doi.org/10.22198/rys.2007.0.a566 [ Links ]

Contreras, F. O. y Hualde Alfaro, A. (2004). El aprendizaje y sus agentes. Los portadores del conocimiento en las maquiladoras del norte de México. Estudios Sociológicos, 22(1), 79-122. [ Links ]

Contreras-Pacheco, O. E. (2018). Gerenciando el conocimiento de los trabajadores del conocimiento: una exploración sobre su compromiso afectivo. Espacios, 39(28), 1-14. [ Links ]

Curtis, M. B. y Taylor, E. Z. (2018). Developmental mentoring, affective organizational commitment and knowledge sharing in public accounting firms. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(1), 142-161. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-03-2017-0097 [ Links ]

Chang-Wook, J., Hea, J. y Myungweon, Ch. (2017). Exploring the affective mechanism linking perceived organizational support and knowledge sharing intention: a moderated mediation model. Journal of Knowledge and Management, 21(4), 946-960. http://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-12-2016-0530 [ Links ]

Chang, Y., Leach, N. y Anderman, E. (2015). The role of perceived autonomy support in principals’ affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Social Psychology of Education, 18(2), 315-336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9289-z [ Links ]

Chin, W. (1988). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.). Methodology for business and management. Modern methods for business research. (pp. 295-336). Manhwah, N.J. Laurence Eribaum Associates Publishers. [ Links ]

Dai, L. y Wang, L. (2016). Psychological contract, reciprocal preference and knowledge sharing willingness. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 4(8), 60-69. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2016.48008 [ Links ]

Diario Oficial de la Federación (1998). Decreto para el fomento y operación de la industria maquiladora de exportación. México. Junio 1 de 1998. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4880755&fecha=01/06/1998 y Consultado: 20/06/2019. [ Links ]

Emecheta, B., Hart, A. y Ojiabo, U. (2016). Personality characteristics and employee affective commitment: Nigeria experience. International Journal of Business and Management Review, 4(6), 69-92. [ Links ]

Fantinato Menegon, L. y Casado, T. (2011). Contratos psicológicos: uma revisão da literatura. Revista de Administración, 47(4), 571-580. [ Links ]

Faraz, M. y Lenka, U. (2017). Linking knowledge sharing, competency development, and affective commitment: evidence from Indian Gen Y employees. Journal of Knowledge Management , 21(4), 885-906. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-08-2016-0334 [ Links ]

Fauzi, M. A., Ling Tan, Ch. N., Thurasamy, R. y Ojo, A. O. (2019). Evaluating academics’ knowledge sharing intentions in Malaysian public universities. Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science. 24(1), 123-143. https://doi.org/10.22452/mjlis.vol24no1.7 [ Links ]

Flores-Alarcón, L. E. (2018). La intencionalidad de la acción en el proceso motivacional humano. Psychologia, 12(2), 115-135. https://doi.org/10.21500/19002386.3973 [ Links ]

Fornell, C. y Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement errors. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50. [ Links ]

García Rubiano, M. y Forero Aponte, C. (2018). Estrés laboral y contrato psicológico como elementos relacionales del cambio organizacional. Revista Diversitas-Perspectivas en Psicología, 14(1), 149-162. https://doi.org/10.15332/s1794-9998.2018.0001.11 [ Links ]

Guerrero Bejarano, M. A. (2016). El contrato psicológico y su relación con el compromiso organizacional. INNOVA Research Journal, 1(12), 44-51. https://doi.org/10.33890/innova.v1.n12.2016.139 [ Links ]

Gupta, V., Agarwal, U. A. y Khatri, N. (2016). The relationships between perceived organizational support, affective commitment, psychological contract breach, organizational citizenship behavior and work engagement. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(11), 2806-2817. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13043 [ Links ]

Gupta, B., Agarwal, A., Samaria, P., Sarda, P. y Bushab, B. (2012). Organizational Commitment and Psychological Contract in Knowledge Sharing Behavior. The Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(4), 736-749. [ Links ]

Henseler, J., Ringle, Ch. y Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , 43(1), 115-135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8 [ Links ]

Hung-Wen, L. y Ching-Hsiang, L. (2009). The relationship among achievement motivation, psychological contract and work attitudes. Social Behavior and Personality, 37(3), 321-328. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2009.37.3.321 [ Links ]

IMIP. (2021). Radiografía socioeconómica del municipio de Juárez. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.imip.org.mx/imip/ y Consultado: 10/12/2022. [ Links ]

INDEX. (2022). Industria maquiladora de exportación. Estadísticas económicas. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://indexjuarez.com/estadisticas/infograma y Consultado:10/12/2022. [ Links ]

INEGI. (2022). Banco de Información Económica. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/indicadores/?tm=0 y Consultado:15/12/2022. [ Links ]

Izzati, U., Suhariadi, F. y Hadi, C. (2015). Personality Trait as Predictor of Affective Commitment. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 3(6), 34-39. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2015.36008 [ Links ]

Kaplan, M. y Kaplan, A. (2018). The relationship between organizational commitment and work performance: A case of industrial enterprises. Journal of Economic and Social Development, 5(1), 46-50. [ Links ]

Li, X., Zhang, S. y Zhou, M. (2017). A multilevel analysis of the role of interactional justice in promoting knowledge-sharing behavior. The mediated role of organizational commitment. Industrial Marketing Management. 62, 226-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.09.006 [ Links ]

Lizote, S. A., Verdinelli, M. A. y do Nascimento, S. (2017). Organizational commitment and job satisfaction: A study with municipal civil servants. Brazilian Journal of Public Administration, 51(6), 947-967. [ Links ]

Loebbecke, C., van Fenema, P. y Powell, P. (2016). Managing inter-organizational knowledge sharing. Journal of Strategic Information Systems. 25(1), 4-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2015.12.002 [ Links ]

Loli, A., Montgomery, W., Cerón, F., Del Carpio, J., Navarro, V. y Llacho, I. (2015). Compromiso organizacional y sentimiento de permanencia de los profesionales en las organizaciones públicas y privadas de Lima Metropolitana. Revista de Investigación en Psicología, 18(1), 105-123. https://doi.org/10.15381/rinvp.v18i1.11781 [ Links ]

Martínez Mejía, E. (2018). Contrato psicológico en empleados mexicanos: Creencias de obligaciones relacionales y transaccionales. Acta de Investigación Psicológica, 9(2), 59-69. https://org/10.22201/fpsi.20074719e.2018.2.05 [ Links ]

Martin-Perez, M. y Martin-Cruz, N. (2015). The mediating role of affective commitment in the rewards-knowledge transfer relation. Journal of Knowledge Management 19(6),1167-1185. https://org/10.1108/JKM-03-2015-0114 [ Links ]

Máynez Guaderrama, A. I. (2011). La transferencia de conocimiento organizacional como fuente de ventaja competitiva sostenible. Modelo integrador de factores y estrategias, Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Popular Autónoma de Puebla, Puebla, México. [ Links ]

Máynez Guaderrama, A. I., Cavazos Arroyo, J., Ibarreche Suárez, S. y Nuño de la Parra, J. P. (2012). Confianza, compromiso e intención para compartir: ¿Variables influyentes para transferir conocimiento dentro de las organizaciones? Revista Internacional Administración & Finanzas, 5(5), 21-40. [ Links ]

Máynez Guaderrama, A. I. y Noriega Morales, S. A. (2015). Transferencia de conocimiento dentro de la empresa: Beneficios y riesgos individuales percibidos. Frontera Norte, 27(54), 29-52. [ Links ]

Máynez Guaderrama, A. I. (2016). Cultura y compromiso afectivo: ¿Influyen sobre la transferencia interna del conocimiento? Contaduría y Administración, 61(4), 666-681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cya.2016.06.003 [ Links ]

Mercurio, Z. A. (2015). Affective commitment as a core essence of organizational commitment: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 14(4), 389-414. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484315603612 [ Links ]

Meyer, J., Allen, N. J. y Smith, C. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538-551. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538 [ Links ]

Millward, L. y Hopkins, L. (1998). Psychological contracts, organizational and job commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 28(16), 1530-1556. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01689.x [ Links ]

Ming-Tien, T., Kun-Shiang, C. y Jui-Lin, C. (2012). The factors impact of knowledge sharing intentions: the theory of reasoned action perspective. Qual Quant, (46), 1479-1491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9462-9 [ Links ]

Mitonga-Monga, J., Flotman, A-P. y Cilliers, F. (2018). Job satisfaction and its relationship with organizational commitment: A democratic republic of Congo organizational perspective. Acta Commercii, 18(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v18i1.578 [ Links ]

Nonaka, I., y Takeuchi, H. (1999). La organización creadora del conocimiento. México, D. F.: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Punniyamoorthy, M., & Asumptha, J. A. (2019). A study on knowledge sharing behavior among academicians in India. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 11(1), 95-113. https://doi.org/10.34105/j.kmel.2019.11.006 [ Links ]

Razmerita, L., Kirchner, K. y Nielsen, P. (2016). What factors influence knowledge sharing in organizations? A social dilemma perspective of social media communication. Journal of Knowledge and Management, 20(6), 1225-1246. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-03-2016-0112 [ Links ]

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S. y Becker, J. M. (2015). SmartPLS3. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.smartpls.com/ y Consultado: 15/06/2019. [ Links ]

Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2(2), 121-139. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01384942 [ Links ]

Sadiya, A. M. y Maimunah, A. (2016). The importance of supervisor support for employee’s affective commitment: An analysis of job satisfaction. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 6(2), 435-439. [ Links ]

Schmidt, G. B. (2016). How adult attachment styles relate to perceived psychological contract breach and affective organizational commitment. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 28(3), 147-170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-016-9278-9 [ Links ]

Shin-Yuan, H., Hui-Min, L. y Yu-Che, Ch. (2015). Knowledge-sharing intention in professional virtual communities: A comparison between posters and lurkers. Journal of the Association for Information and Technology, 66(12), 2494-2510. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23339 [ Links ]

Smith, C. (2017). An analysis of structural social capital and the individual’s intention to share tacit knowledge using Reasoned Action Theory. The Journal of applied Business Research, 33(3), 475-488. https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v33i3.9940 [ Links ]

Shuang-Shii, Ch., Kun-Shiang, Ch. y Ming-Tien, T. (2015). Exploring the antecedents that influence middle management employees, knowledge-sharing intentions in the context of total quality management implementations. Total Quality Management, 26 (1), 108-122. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2013.809941 [ Links ]

Tangaraja, G., Rasdi, R., Samah, B. y Ismail, M. (2016). Knowledge sharing is knowledge transfer: a misconception in the literature. Journal of Knowledge Management , 20(4), 653-670. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2015-0427 [ Links ]

Villalpando, P. (2004). La evolución de la industria maquiladora en México. Innovaciones de Negocios. 1(2). 321-330. [ Links ]

Vesga Rodríguez, J. J. (2011). Los tipos de contratación laboral y sus implicaciones en el contrato psicológico. Pensamiento Psicológico, 9(16), 171-181. [ Links ]

Woolley, D. (2015). Two issues to consider in digital piracy research: The use of Likert like questions and the theory of reasoned action in behavioral surveys. Journal of Legal, Ethic and Regulatory Issues, 18(3), 63-67. [ Links ]

Wu, W.-L. (2013). To share knowledge or not: dependence on knowledge-sharing satisfaction. Social Behavior and Personality, 4(1), 47-58. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2013.41.1.47 [ Links ]

Yong, S. H.,Byoungsoo, K. y Heeseok, L. (2016). What drives employees to share their tacit knowledge in practice? Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 14(3), 295-308. https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2014.32 [ Links ]

Zhike, L. y Ting, X. (2018). Psychological contract breach, high performance work system and engagement the mediated effect of person-organization fit. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 29(7), 1257-1284. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1194873 [ Links ]

Received: July 23, 2020; Accepted: February 03, 2023; Published: February 16, 2023

texto en

texto en