Introduction

The genus Tilia L. originated in East Asia; one of its diagnostic characters is the occurrence of a cymose inflorescence partially fused to a winged bract (Peng et al., 2019). Approximately 23 species are recognized worldwide, distributed mainly in the template zones of the Northern Hemisphere, with recent occurrence in the tropics of Mexico and Vietnam (Pigott, 2012). All species are deciduous with alternate, simple, stipulate, petiolate leaves and laminas with dorsiventral structure. Trichomes are common on both leaf surfaces with their type and distribution significantly differing among species, providing relevant taxonomic information. However, despite these differences, the delimitation of some taxa is still complicated (Pigott, 2012; McCarthy and Mason-Gamer, 2016, 2020; Xie et al., 2023).

The greatest leaf and floral morphological variation in the genus occurs in the Eastern Asian species, which has allowed taxonomists to characterize and recognize species (Pigott, 2012). Seventeen species had been described from this region: Tilia endochrysea Hand-Mazz., T. henryana Szyszył., T. amurensis Rupr., T. japonica (Miq.) Simonk., T. kiusiana Makino & Shiras. ex Shiras., T. mongolica Maxim., T. paucicostata Maxim., T. callidonta Hung-T. Chang, T. chinensis Maxim., T. chingiana Hu & Cheng, T. concinna Pigott, T. mandshurica Rupr. & Maxim., T. maximowicziana Shiras., T. miqueliana Maxim., T. nobilis Rehder & E.H. Wilson, T. oliveri Szyszył., and T. tuan Szyszył. In addition to leaf traits for some species of this region, other characters have been used to distinguish taxa, e.g., the strongly ribbed fruit of T. chinensis (Zhu, 1991; Pigott, 2012).

For American lindens, Jones (1968) identified four species (Tilia americana L., T. caroliniana Mill., T. heterophylla Vent. and T. mexicana Schltdl.) by the leaf color and density of pubescence. In contrast, Hardin (1990), based on trichome density and morphology, recommended treating North American lindens as a single species (T. americana sensu lato) with four varieties (T. americana var. americana, T. americana var. caroliniana (Mill.) Castigl., T. americana var. heterophylla (Vent.) Loudon, and T. americana var. mexicana (Schltdl.) Hardin). In a more extensive work, Pigott (2012) incorporated the number of arms of stellate trichomes and their length as relevant characters to differentiate species and infrageneric categories recognizing T. americana with two varieties (T. americana L. var. americana and T. americana L. var. neglecta (Spach) Fosberg) and T. caroliniana with four subspecies (T. caroliniana subsp. caroliniana, T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray, T. caroliniana subsp. heterophylla (Vent.) Pigott and T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis (Rose) Pigott. Recently, McCarthy and Mason-Gamer (2020) included 12 leaf morphological characters, such as leaf length and width, concluding that the unclear boundaries between the characters support the recognition of a single species, T. americana s.l., in contrast to their previous phylogeographic study in which they identified different groups for North American species based on two chloroplast regions (McCarthy and Mason-Gamer, 2016).

For the non-American lindens, Pigott (2012) recognized four taxa distributed in Europe and western Asia (Tilia cordata Mill, T. dasystyla Steven, T. platyphyllos Scop. and T. tomentosa Moench, but the circumscription of some of them has been problematic. For example, among the species accepted by Maleev (1949) was T. sibirica Bayer, which shows small morphological differences with respect to T. cordata, but nevertheless, geographically their separation is clear, so Pigott (2012) assigned it the rank of subspecies (T. cordata subsp. sibirica Pigott). In the case of T. dasystyla, Loria (1967) proposed treating it as a subspecies of T. platyphyllos, but both show significant morphological differences, for example, in the number of teeth and type of trichomes, so they are currently recognized as distinct species.

Although the delimitation of species of Tilia is mainly based on the morphological characteristics of the leaves, resulting complicated for the wide variation they present, leaf architecture and anatomy have been little explored. For other taxa, leaf anatomy has supported the separation of species with micro-morphological or anatomical characters (Andrés-Hernández and Terrazas, 2006; Downing et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2008; Silva Araújo et al., 2010; Solano et al., 2017; da Silva-Luz et al., 2019), and the venation pattern has been particularly important in helping to identify some groups at different hierarchical classification levels (Hickey, 1979; Hetterscheid and Hennipman,1984; Sajo and Rudall, 2002; Martínez-Millán and Cevallos-Ferriz, 2005; Martínez-Cabrera et al., 2007; Andrés-Hernández and Terrazas, 2009; Cervantes et al., 2009; Pacheco-Trejo et al., 2009; Tejero-Diez et al., 2010; Andrés-Hernández et al., 2012; do Carmo et al., 2019). Therefore, in this work we describe and compare the leaf architecture and anatomy of eight species and four subspecies of the genus Tilia representing the American species and others which restrict their distribution to Asia and Europe, in order to identify characters that contribute to the delimitation and identification of these taxa.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

Leaves of eight species and four subspecies were studied (Appendix 1) which represent the North American species and different species centering their distribution in Europe and Asia. These studied species belong to different sections and clades according to Xie et al. (2023). Leaves were collected from individuals throughout the Tilia distribution area in Mexico (Appendix 1) or removed from specimens in the herbarium MEXU or the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK. For the field material, at each site, four or five mature leaves of a flowering branch were collected following the recommendation by Pigott (2012). These leaves were fixed in formalin-acetic acid-ethyl (Ruzin, 1999) for 24 hours and then washed and changed to glycerin-ethyl alcohol-water (1:1:1) until processing began. Voucher specimens were deposited in the herbarium MEXU. For the dried leaves from the herbarium MEXU (Thiers, 2023) and Kew Royal Botanic Gardens (Appendix 1), these were rehydrated in hot water for 30 minutes, and then fixed in the same way as the leaves collected in the field.

Leaf clearing

One to three leaves per individual were cleared in a 20% NaOH at 60 °C for at least 72 h, then washed with tap water and placed in sodium hypochlorite (50% commercial bleach) until they were whitish, and washed with tap water until no bleach odor was present. The samples were then dehydrated for 24 h with ethanol series (50, 70 and 96%), placed in a modified benzyl benzoate clearing solution (Martínez-Cabrera et al., 2007) for 15 days, and when completely translucid, placed in 96% ethanol for 24 h. The leaves were stained with Safranin O 5% (96% ethanol) for 1 h, then washed with 100% ethanol until an adequate contrast between the background and veins was achieved. The dehydration was followed by two changes of xylene and the cleared leaves were mounted using synthetic resin. The leaf architecture describes the form of those elements constituting the external structure, including venation pattern, marginal configuration, leaf shape, and gland position (Hickey, 1973), which were named following the terminology of Ash et al. (1999).

Leaf anatomy

The middle segments of the lamina including midvein to margin of 3-5 leaves per taxon were rehydrated with a 5% NaOH for five minutes and washed with tap water for 30 min, then they were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ter-butanol (10-100%) in an automatic tissue processor (TP1020 Leica, Westlar, Germany) remaining for 24 hours in each concentration and embedded in paraplast (Leica Paraplast Plus). Transverse and paradermal sections of 12 µm in thickness were cut with a rotatory microtome (RM2125 Leica, Westlar, Germany). The sections were mounted on slides with Haupt’s adhesive (Johansen, 1940). For deparaffinization, the sections remained in the oven for 10 min, then three xylene changes were made for five minutes each, followed by the decreasing ethanol series (100%-50%) for 5 min each. Staining was performed with Safranin-Fast green (Ruzin, 1999) and sections were mounted with synthetic resin. The general terminology for leaf anatomy followed Metcalfe and Chalk (1950). The surface epidermal characteristics were described according to Koch et al. (2009), trichome type following Hardin (1990) and domatia type according to Wilkinson (1979). For the quantitative anatomical characteristics, five measurements or counts were made per field in five fields per individual per species and subspecies. For trichome density per mm2 only fascicled and stellate trichomes present exclusively in the intercostal regions of the lamina were counted and arm length was measured only in four-armed stellate trichomes for being the most constant type when present, according to Hardin (1990) and Pigott (2012). For adaxial and abaxial cuticles and mesophyll their width was measured and for the mucilage cavities in the midvein their number counted, and the diameter measured. A histochemical test was performed to detect the presence of mucilage with Toluidine Blue (Ventrella et al., 2013).

For observations in the scanning electron microscope, leaf segments were dehydrated in a gradual series of ethyl alcohol (50-100%), brought to the critical point and covered with a gold film in an ionizer (Hitachi-S-2460N, Tokyo, Japan). Photographs of its adaxial and abaxial surfaces were taken with a Hitachi-S-2460N (15 Kv) microscope at the Institute of Biology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Results

Leaf architecture

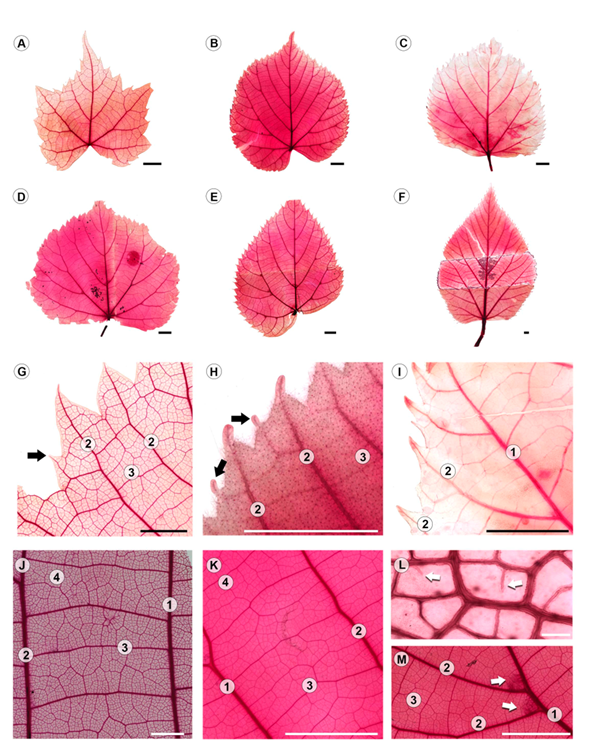

All species have alternate leaves, with a relatively long petiole and two generally lanceolate stipules. The lamina is deltoid, orbicular, suborbicular or broadly ovate, base asymmetric, apex acuminate varying from 0.3 cm in T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis to 1.6 cm in T. mongolica (Appendix 2) and with toothed margins (Fig. 1A-F). Teeth of the first and second order are variable in number per cm and width of the base of the tooth, e.g., having five teeth per cm in T. cordata and one in T. oliveri, with the largest base in T. caroliniana subsp. caroliniana (Appendix 2), and also variable in shape and apex (Fig. 1G-I, Table 1). Basal venation is actinodromous with 4-7 veins, compound agrophic veins are present, secondary venation is craspedodromous or semicraspedodromous (Table 1), major secondary attachment to midvein excurrent or decurrent, tertiaries are percurrent straight or slightly sinuous (Fig. 1J, K), quaternary variable percurrent and quintenary reticulate. Areolation is well-developed; areoles vary in number from 10 to 29 /mm2 (Appendix 2), with unbranched veinlets or absent (Fig. 1L).

Figure 1: Leaf architecture of Tilia L. A-F. General morphology. A. T. mongolica Maxim.; B. T. platyphyllos Scop.; C. T. oliveri Szyszył.; D. T. cordata Mill.; E. T. endochrysea Hand-Mazz.; F. T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis (Rose) Pigott; G-I. first and second order (black arrows) teeth, G. T. mongolica Maxim.; H. T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis (Rose) Pigott; I. T. oliveri Szyszył.; J, K. tertiary veins, J. T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray; K. T. cordata Mill.; L. well-developed areole with unbranched veinlets (white arrows), T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray; M. domatia tuft like trichomes (white arrows), T. endochrysea Hand-Mazz. Scale is 5 mm in A-F, H-K, M; 2 mm in G; 100 µm in L; number of vein order = 1, 2, 3, 4.

Table 1: Variation of the architecture and anatomy qualitative characters in the studied Tilia L. taxa. LS=lamina shape; BS=base shape, asym=asymmetric, cun cuneate, cord=cordate, sli_sym=slightly symmetric, sym=symmetric, trun=truncate; SV=secondary venation pattern, cra=craspedodromous, secra=semicraspedodromous; VU=junction secondary venation; OT=teeth order; TS=tooth shape; TA=tooth apex; DO=domatia, presence +, absence -; PB=pubescence, presence +, absence -; AWAC=anticlinal walls of abaxial epidermal cells; MV=midvein type, 1, 2 and 3 (see text for explanation).

| Species | LS | BS | SV | VU | OT | TS | TA | DO | PB | AWAC | MV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tilia americana L. | suborbicular/ widely ovate | asym cord | cra | decurrent | 1st | flexuous-convex | long | + | + | undulate | 3 |

| T. amurensis Rupr. | circular/ triangulare ovate | asym cord | secra | decurrent | 1st | concave-flexuous | long | + | + | undulate | 3 |

| T. caroliniana subsp. caroliniana | ovate | sli_asym | cra | excurrent | 1st | flexuous-convex | short | + | + | undulate | 3 |

| T. caroliniana Mill. subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray | orbicular/ suborbicular | asym cord | cra | excurrent | 1st, 2nd | concave-flexuous or concave-convex | short | + | + | straight, undulate | 1, 3 |

| T. caroliniana subsp. heterophylla (Vent.) Pigott | broadly ovate | asym cord | cra | excurrent | 1st | flexuous-flexuous or concave-flexuous | long | + | + | undulate | 3 |

| T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis (Rose) Pigott | orbicular/ suborbicular | asym cord | cra | excurrent | 1st, 2nd | concave-flexuous or concave-convex | long | + | + | straight | 1, 2 |

| T. cordata Mill. | orbicular | sli_asym | secra | decurrent | 1st | concave-flexuous | long | + | + | undulate | 3 |

| T. endochrysea Hand-Mazz. | ovate | asym cun | secra | decurrent | 1st | concave-flexuous or straight-concave | long, sinuous | + | - | undulate | 2 |

| T. mongolica Maxim. | deltoid | sym | cra | decurrent | 1st, 2nd | straight-straight or flexuous-convex | long, slender, sinuous | - | + | undulate | 3 |

| T. oliveri Szyszył. | orbicular | sli_asym | cra | decurrent | 1st | straight-flexuous or retroflexed-straight | short | + | + | U-undulate | 3 |

| T. platyphyllos Scop. | orbicular/ suborbicular | asym trun | cra | decurrent | 1st | flexuous-convex | short | + | straight | 3 |

Leaf anatomy

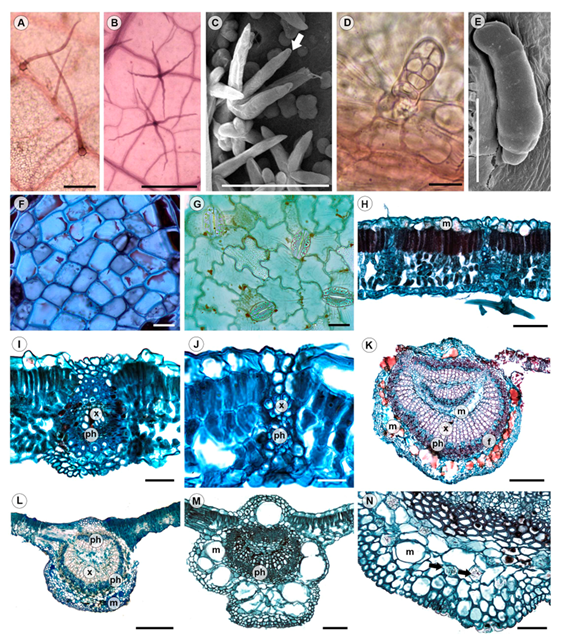

The leaves are hypostomatic. In superficial view, adaxial epidermis is composed of more or less rectangular cells with straight anticlinal walls, while those of the abaxial epidermis have straight or wavy anticlinal walls with anomocytic stomata in surface view (Fig. 2F, G, Table 1). Most species are pubescent, but glabrous in T. endochrysea (Table 1). The adaxial surface is mostly glabrous or with sparse acicular trichomes and abaxial surface mostly pubescent. The acicular trichomes occur in the vein axils of primary-secondaries or secondaries-tertiaries in most species (Fig. 1M), conforming the domatia consisting of a tuft of hairs. The fasciculate and stellate trichomes are mainly in the intercostal region, and the glandular trichomes, which are long, bulbose or with bottle shape, occur on veins (Fig. 2A-E, Table 2). The stellate trichomes are variable in the number of branches having four to eight arms and their presence varies from rare to abundant among species, being most common the ones with eight arms in the taxa studied (Table 3).

Figure 2: Leaf anatomy of Tilia L. A-E. type of trichomes. A. acicular trichome (cl), T. platyphyllos Scop.; B. stellate trichome with four arms (cl), T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray; C. fasciculate trichome (white arrow, sem), T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray; D. bulbose trichome (cl), T. mongolica Maxim.; E. bottle trichome (sem), T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray; F-J. tissue anatomy. F. adaxial epidermis with straight anticlinal walls (ps), T caroliniana subsp. heterophylla (Vent) Pigott; G. abaxial epidermis with undulate-walled epidermal cells and anomocytic stomata (ps), T. cordata Mill.; H. dorsiventral mesophyll, vascular bundles with extension (cs), T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray; I, J. detail of vascular bundles with extension (cs); I. T. cordata Mill.; J. T. platyphyllos Scop.; K-M. midvein types (cs); K. type 1, T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray; L. type 2, T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis (Rose) Pigott; M. type 3, T. oliveri Szyszył.; N. detail of druses (yellow arrows) and mucilage cavities in midvein (cs), T amurensis Rupr. cl=cleared leaf; ps=paradermal section; sem=scanning electron microscopy; cs=cross section. Scale is 100 µm in A-C, M; 20 µm in D, F, G; 50 µm in E, H-J, N; 300 µm in K, L. f=fibers; m=mucilage; ph=phloem; x=xylem.

Table 2: Type of trichomes, their position within the leaf and abundance in the studied Tilia L. taxa. Mv=midvein, Miv=minor veins, Int=intercostal region, --=absent, r=rare, o=occasional, a=abundant.

| Species | Type of trichomes | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acicular | Fasciculate | Glandular | Stellate | |||||||||

| Mv | Miv | Int | Mv | Miv | Int | Mv | Miv | Int | Mv | Miv | Int | |

| Tilia americana L. | - | o | - | o | o | - | o | o | - | r | - | r |

| T. amurensis Rupr. | - | - | - | r | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| T. caroliniana Mill. subsp. caroliniana | o | o | - | o | - | o | - | - | - | r | - | r |

| T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray | o | r | - | o | - | o | a | a | a | a | a | a |

| T. caroliniana subsp. heterophylla (Vent) Pigott | - | - | - | - | - | - | a | a | a | a | a | a |

| T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis (Rose) Pigott | r | - | o | - | o | a | a | a | a | a | a | |

| T. cordata Mill. | - | o | - | o | - | - | a | a | - | r | - | r |

| T. endochrysea Hand-Mazz. | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| T. mongolica Maxim. | r | - | - | r | r | - | r | - | - | - | - | - |

| T. oliveri Szyszył. | o | - | - | - | - | - | a | o | - | a | a | a |

| T. platyphyllos Scop. | a | a | - | - | r | - | a | a | - | - | - | - |

Table 3: Number of arms of the stellate trichomes and their abundance on the leaves of the studied Tilia L. taxa. --=absent, r=rare, o=occasional, a=abundant.

| Species | Number of arms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Tilia americana L. | - | - | - | r | - | - |

| T. caroliniana Mill. subsp. caroliniana | r | - | - | - | - | r |

| T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray | - | a | o | o | r | o |

| T. caroliniana subsp. heterophylla (Vent.) Pigott | - | r | - | - | - | a |

| T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis (Rose) Pigott | - | r | o | r | r | a |

| T. cordata Mill. | - | - | - | r | - | - |

| T. oliveri Szyszył. | - | - | - | - | - | o |

In transverse sections, both epidermises are simple, and some cells contain mucilage (Fig. 2H). The mesophyll is dorsiventral, with one or two layers of palisade parenchyma cells, variable in size and some cells may contain prismatic crystals; the spongy parenchyma on the abaxial surface has two or three cell layers of variable shape (Fig. 2H-J). The vascular bundles are collateral, the bundle sheath sometimes has prismatic crystals and bundle sheath extensions are present towards both epidermises in all orders of venation. The cells of the bundle sheath extensions consist mostly of fibers, but T. mongolica, T. oliveri and T. platyphyllos have parenchyma cells (Fig. 2I, J). In the midvein, the epidermal cells are smaller than in the lamina; below the epidermises there are two to five and rarely up to seven layers of annular collenchyma, sometimes with druses and rarely prisms. The parenchyma between the collenchyma and the vascular tissue may contain druses or prisms (Fig. 2N) and mucilage cavities are common. One or no mucilage cavity is present on the adaxial surface and three to nine cavities of variable size on the abaxial one (Appendix 2, Fig. 2K-N). The vascular tissue has different arrangements always surrounded by two to five layers of thick-walled fibers and can be classified into three types (Fig. 2K-M, Table 1). Type 1 has a ring-shaped vascular bundle, continuous xylem and discontinuous phloem at the center of the ring, and an inverted vascular bundle dividing the pith (Fig. 2K). It is present in most samples of T. caroliniana subsp. floridana and few samples of T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis. The type 2 has a ring-shaped vascular bundle with continuous xylem and discontinuous phloem towards the adaxial surface and parenchyma cells at the center of the ring, the pith (Fig. 2L). This type 2 occurs in T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis and T. endochrysea. In type 3, the vascular bundle is forming an arc with the ends curved towards the center or invaginated and distinctive pith of parenchyma cells (Fig. 2M). It is the most common type observed in the genus (T. americana, T. amurensis, T. caroliniana subsp. caroliniana, T. caroliniana subsp. heterophylla, T. cordata, T. mongolica, T. oliveri, and T. platyphyllos).

Based on the character and character states described above, we were able to produce a key to identify the eight species and the subspecies of Tilia studied.

Identification key

1a. Abaxial surface pubescent ……..……………....…………………………………….…... 2

1b. Abaxial surface glabrous ………...………………………….. T. endochrysea Hand-Mazz.

2a. Pubescence with stellate trichomes ………….....…………………………………….…. 3

2b. Pubescence without stellate trichomes …………………………….….……………….... 9

3a. Glandular trichomes absent, few fasciculate trichomes …….………….….. T. amurensis Rupr.

3b. Glandular and acicular trichomes present …………..………………………..…..…….. 4

4a. Leaf deltoid, domatia absent, tooth base 0.5 cm wide, glandular and acicular trichomes on veins rare ………….………………..…………………………….……… T. mongolica Maxim.

4b. Leaf orbicular or suborbicular, domatia present, tooth base < 0.3 cm wide, glandular and acicular trichomes on the veins abundant …………………..………...….. T. platyphyllos Scop.

5a. Four-armed stellate trichomes present ..…………………………………..……...………. 6

5b. Four-armed stellate trichomes absent ……………………………………….…...……….. 8

6a. Four-armed stellate trichomes abundant …………..……................ T. caroliniana subsp. floridana (Small) A.E. Murray

6b. Four-armed stellate trichomes sparce …………….…………………...…...……………… 7

7a. Four-armed stellate trichomes 242.5±95.4 µm long, teeth 2 per cm, trichomes > 45 per mm2, midvein type 3 …………………………….... T. caroliniana subsp. heterophylla (Vent.) Pigott

7b. Four-armed stellate trichomes 332.09±106.1 µm long, teeth 3 per cm, trichomes 0-25 per mm2, midvein type 2, rarely type 1 …… ...……...… T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis (Rose) Pigott

8a. Eight-armed stellate trichomes absent …………………………….…………………..…… 9

8b. Eight-armed stellate trichomes present ……………….………………………….….……10

9a. Venation semicraspedodromus, glandular trichomes on veins abundant, mean mesophyll width 102 µm, 3-6 cavities towards the abaxial surface ……………………..…. T. cordata Mill

9b. Venation craspedodromous, glandular trichomes on veins occasional, mean mesophyll width 140 µm, < 3 cavities in midvein towards abaxial surface ………………….…….. T. americana L

10a. Leaf apex short (0.8±0.5 cm), junction secondary venation excurrent, 3- and 8-armed stellate trichomes rare, glandular trichomes on veins absent, abaxial epidermal cells undulate, 3 cavities in midvein towards abaxial surface ………………..….. T. caroliniana subsp. caroliniana Pigott

10b. Leaf apex long (1.1±0.2), junction secondary venation decurrent, 8-armed stellate trichomes occasional, glandular trichomes on veins abundant, abaxial epidermal cells undulate, 8-10 cavities in midvein towards abaxial surface …………………………………. T. oliveri Szyszył.

Discussion

Diagnostic characters

Comparison of the leaf architecture and anatomy of the species and subspecies here studied yielded commonalities that can be considered characteristic of the genus, such as the occurrence of mucilage cavities. Despite the wide variation found, unique combinations of characters were discovered that contribute to the recognition of species and subspecies (see key above). For example, T. mongolica was the only species with a deltoid lamina and without domatia. Tilia oliveri had the largest lamina and epidermal cells on the abaxial surface with anticlinal U-undulate walls and T. americana was the species with the thickest mesophyll. Tilia caroliniana subsp. occidentalis was characterized by lamina with three teeth per cm and the arms of four-armed stellate trichomes with a length of 332 µm. Tilia caroliniana subsp. heterophylla was distinguished by having higher density of trichomes (49 trichomes per mm2) and shorter arms (242 µm).

Tilia cordata, T. endochrysea and T. amurensis were distinctive by the decurrent union of the secondary veins and absence of stellate trichomes with four arms. Moreover, T. endochrysea differed from the other two species by the midvein type 2 and T. platyphyllos was characterized by teeth with narrower bases. This work provided characters that can be incorporated into the molecular phylogenetic evidence to support clades and contribute to the understanding of species complexes sensu Xie et al. (2023), as well as to support the classification of Pigott (2012) for various species of Tilia.

Leaf architecture and anatomy

When comparing the species described in this work with the descriptions of other studies, as for Tilia mandshurica and T. chingiana from Asia (Hickey, 1979; Ash et al., 2009), there were coincidences mainly in the acuminate apex, the cordate base, the basal actinodromous venation pattern and the compound agrophic veins, as well as quaternary and quintenary veins with well-developed areoles. For the genus, Hickey (1979) described teeth of only one order for T. mandshurica and T. chingiana, whereas in the revised specimens of T. caroliniana subsp. floridana, T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis and T. mongolica, first and second order teeth were found. Xie et al. (2023) considered the number of teeth as a relevant character to differentiate T. endochrysea from the other species, as it is the one with the lowest number of teeth. However, Pigott (2012) pointed out that the number of teeth in T. endochrysea is variable among individuals and within the same individual, which is consistent with the results presented here. In addition, other species here studied, T. mongolica and T. oliveri, had a lower number of teeth per cm than T. endochrysea.

Some leaf architecture traits are common in various genera of Malvaceae. For example, Sterculia L. (Hussin and Sani, 1998) and Tilia share the presence of unbranched veinlets, while they differ from those of Mortoniodendron Standl. & Steyerm. where four or more times branched veinlets predominate (Solís-Montero et al., 2013). Corney et al. (2012) separated three species of Tilia (T. cordata, T. platyphyllos and T. americana), using tooth characteristics such as size, shape and insertion angles. In the present work, these characteristics were not explored in depth, but the tooth base width and the distance between teeth evaluated here proved to be important quantitative characters for separating the species. We suggest in future studies to use the algorithms generated by Corney et al. (2012) and to extend the analysis to the rest of the species of Tilia.

Regarding the anatomy, the trichome types identified in the species studied in this work corresponded to the four types reported by Hardin (1990) for North American species: acicular, fasciculate, stellate, and glandular. For the last type, Ramírez-Díaz et al. (2019) recognized three different types: bulbous, bottle-shaped, and long. The three types occurred in Tilia caroliniana subsp. floridana, whereas the bulbous type was common in all the species studied here. Eglandular and glandular trichome diversity has been described for other Malvaceae. Only domatia consisting of a tuft of hairs with acicular trichomes were found for the species of Tilia studied, having less diversity than other Malvaceae with more than one type of domatia (Solís-Montero et al., 2009). The multicellular arms or base of the stellate trichomes described for other members of this family were not found in Tilia (Ramayya and Rao, 1976; Rao and Ramayya, 1987; Sharma, 1990). Although wide eglandular trichome variation has been found by other authors, especially for the North American taxa (Hardin, 1990; Pigott, 2012; McCarthy and Mason-Gamer, 2020), our results suggest that the occurrence becomes informative when the number of arms and their length are accounted for the different types of trichomes, as shown here especially for the four-armed trichomes.

Metcalfe and Chalk (1950) reported anomocytic and tetracytic stomata for the genus. However, in the species and subspecies studied here, only anomocytic stomata were found. The stomata were restricted to the abaxial surface in the Tilia species (hypostomatic leaves) as in Theobroma L. (Garcia et al., 2014), whereas in other Malvaceae amphistomatic leaves have been found (de Meneses Silva et al., 2023).

Our observations in the lamina agree with the description of the genus made by Pigott (2012) for different species, as in the presence of palisade parenchyma in the mesophyll formed by one or two layers of cells and the lax spongy parenchyma reported for Tilia cordata and T. platyphyllos. In addition, Hanson (1917) observed that in the leaves of T. americana with greater exposure to the sun, the mesophyll is composed only of palisade cells, which could be comparable to the anatomy found in some individuals of T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis collected in the states of Chihuahua and Oaxaca in Mexico.

The studied species and subspecies of Tilia can be classified as heterobaric because vascular bundle sheath extensions were always present, and they extend towards both epidermises. In species of Sterculia, the sheath extension only extends towards one of the epidermises. For example, S. foetida L. presents fiber sheath extending towards the adaxial side of the lamina (Hussin and Sani, 1998). According to Rodrigues et al. (2017), this incomplete bundle sheath extensions behave photosynthetically as homobaric leaves. Only five taxa studied, T. amurensis, T. caroliniana subsp. floridana, T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis, T. cordata and T. platyphyllos showed sclerified sheath extensions as described for other Malvaceae such as Eriotheca gracilipes (K.Schum.) A.Robyns and Pseudobombax longiflorum (Mart. & Zucc.) A.Robyns (Rodrigues et al., 2017). As mentioned by Karabourniotis et al. (2021), these bundle sheath extensions may be contributing to transfer light to the mesophyll and improving photosynthetic performance, as well as giving toughness of the leaves. It will be interesting to evaluate the occurrence of bundle sheath extensions in other Malvaceae to support the assertion that this is a diagnostic character for the tree species of the family.

Three types of vascular bundle arrangement in the midvein were described for the species and subspecies of Tilia studied. It is important to emphasize that type 3 is the most common one, being found in five species and two subspecies studied in this work. The type 1 was observed in most samples of T. caroliniana subsp. floridana and very few samples of T. caroliniana subsp. occidentalis. The study of the missing species of Tilia from Europe and Asia will allow us to confirm the diagnostic value of the midvein vascular type.

Mucilage cells in the epidermis and in cavities are common in Malvaceae (Judd and Manchester, 1997), and they have been reported in species of the genera Sterculia (Hussin and Sani 1998), Mortoniodendron (Solís-Montero et al., 2013) and Ceiba Mill. (Perrota et al., 2007). Various authors (Metcalfe and Chalk, 1950; Pizzolato, 1977) pointed out that, in addition to the mucilage-secreting cells in the epidermis, Tilia presents mucilage cavities that can be found both in the mesophyll and around the vascular bundles of the midvein. Cavities and canals have been recognized in various plant families and they varied in size and position (Turner et al., 1998; Martínez-Quezada et al., 2022; Tölke et al., 2022), and both may be present in the same taxa. However, we consider that Pigott (2012) was referring to the cavities here shown because we were not able to recognize epithelial cells, a feature which defines the canal. Therefore, we consider that in Tilia only cavities are present as mentioned for other authors (Judd and Manchester, 1997).

Conclusions

Leaf characters, architecture and anatomy evaluated here contribute to differentiate Tilia species and subspecies of North America and the studied lindens of Asia and Europe. The unique combination of features supports species and subspecies. Morphology of teeth in the leaves is important if studied on the flowering branches as Pigott (2012) had pointed out. Moreover, the diversity of trichomes need to be evaluated in the different leaf regions and their arm length needs to be measured. The secretory structure of Tilia is the cavity since no epithelial cells were found. Different combinations of leaf characters are promising for the systematics of the genus Tilia. The characteristics of the leaf lamina should not be the only ones used in the taxonomy of the genus; it is proposed to explore the inflorescence and the fruits.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)