Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Frontera norte

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0260versión impresa ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.28 no.55 México ene./jun. 2016

Artículos

Street Art at the Border: Representations of Violence and Death in Ciudad Juárez*

Arte urbano fronterizo: Representaciones de violencia y muerte en Ciudad Juárez

Diana Alejandra Silva Londoño**

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. diana.aiejandra.silva@gmaii.com.

Date of receipt: October 6, 2014.

Date of acceptance: February 31, 2015.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is to interpret the various meanings that violence and violent deaths have in Ciudad Juárez, through their representation in street art. Using in-depth interviews, participant observation, explorations of the city, and a photographic record of the artistic displays of border street art collectives, the way youths perceive themselves is explored, including how they see their biographical experiences and the agency of their art in contexts of violence.

Keywords: 1. street art, 2. violence, 3. death, 4. Ciudad Juárez, 5. Mexico.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este artículo es realizar una lectura interpretativa de las tramas de sentido de la violencia y la muerte violenta en Ciudad Juárez, a partir de su representación en el arte urbano. Por medio de entrevistas en profundidad, observación participante, recorridos urbanos y registro fotográfico de la producción artística de los colectivos de arte urbano fronterizo se explora cómo las/os jóvenes se conciben a sí mismas/os, perciben su experiencia biográfica y cuáles son sus márgenes de agencia desde las prácticas artísticas en contextos de violencia.

Palabras clave: 1. arte urbano, 2. violencia, 3. muerte, 4. Ciudad Juárez, 5. México.

INTRODUCTION

Ciudad Juárez is one of the cities most affected by the wave of violence Mexico has undergone in recent years, particularly from carrying out the so-called "war on drugs" promoted by Felipe Calderón when he was president from 2006-2012. Although the city already had rates of violence above the national average, they would reach unprecedented levels beginning in 2008. This situation, added to a general impunity, profoundly affected the city's daily life. In this context, young people have become key social actors upon being identified as the main victims and victimizers, but above all because they have been the subjects of a wide variety of cultural and political initiatives.

This article enquires into the emergence and transformation of the subjectivities of the young women and men who, from the perspective of urban art, articulate and represent the violence they experience daily. Using in-depth interviews, participant observation, exploration of the city, and a photographic record of their artistic production, it explores how these young people conceive of themselves, perceive their biographical experience, and what their agency is from artistic practices (resistance) in an urban space associated with systematic violence and fear. It argues that through the practice of art, it is possible to reconstruct the sense of life in the face of death, where they are producers of intersubjective spaces where they can share the indignation, fear, and suffering that is directly or indirectly experienced (Jimeno, 2008). This work seeks to give credit to the subjective experiences gained in contexts of violence and the way in which the subjects respond to them through a wide gamut of resources and tactics (Blair, 2004; Das and Kleinman, 2000).

First, the most important aspects of the problem of systematic violence in Ciudad Juárez are presented, with the goal of contextualizing the narratives and artistic production that are analyzed throughout the text. Then, the theoretical and methodological elements are laid out from a sociocultural perspective that guides our understanding in terms of subjectivity in contexts of violence. The third section describes the emergence and functioning of the multidisciplinary collective of urban art Rezizte (Resist). The experience of the members of the collective and their artistic production, particularly in terms of the series "El sicario" (The Hit Man) and art created in memory of young people who were killed, is then discussed. Finally, the conclusions discuss the principal findings of this research.

SYSTEMATIC VIOLENCE IN CIUDAD JUÁREZ

The violence is not the result of accidental events. It is produced by a complex series of structural conditions and circumstances that converge on each other. This is how Aziz Nassif (2012) put it in describing the violence that cuts across Ciudad Juárez. If before 2008 the border city already had a high rate of violence that made it one of the most violent cities in Mexico, beginning that year, with the presence of military forces and the upsurge of territorial disputes between the drug cartels, it became known as the most violent city in the world for three consecutive years.1 During that time, the extreme violence made itself known with an unheard of magnitude and visibility in public spaces, collapsing the existing interpretative systems. The cruelty and the dehumanization with which thousands of bodies were thrown onto public streets, hung, wrapped in blankets, decapitated, placed in trunks, bound, and burned, among other things, unleashed a vocabulary of horror that denies the unique character of those killed and denies families and society in general their right to properly mourn.

It is estimated that between January 2007 and December 2012, 11 078 people were slain in Ciudad Juárez (Inegi, 2013). Out of that total, officials have reported that 91 percent were men; it is assumed that most were young men from low socioeconomic strata. If beginning in 2011 the homicides diminished considerably, these still have not gone down to pre-2008 levels. Aside from individual deaths, there have been at least 25 massacres of young people in the last five years, a situation that caused some analysts to start referring to juvenicidio (youthicide) as an analytical category (Orquiz, 2013; Quintana, 2010). This trail of violence has left a countless number of orphans, widows, and mothers and fathers without children, as well as displacing families by force.

To understand the causes that produced this scenario of systematic violence it is necessary to refer to a series of structural and situational factors. Among the first are economic, urban, demographic, social, and cultural factors that are initiators and detonators of systematic violence widely developed in other research (Barraza, 2009; Jusidman, 2007). This work emphasizes Juárez's border-city status, with a productive restructuring, resulting from the installation of the maquiladora export industry, and the absence of social policies. In effect, Ciudad Juárez shares a wide border with the United States, particularly with Texas and New Mexico; this is an important point for conducting commercial and productive activities of the maquiladora industry, as well as a wide diversity of illicit activities, including drug trafficking, migrant smuggling, human trafficking, arms smuggling, etc.

The push from the maquiladora industry attracted transnational capital that required intensive utilization of labor; as a result of this process of economic restructuring, the city became a pole of attraction for thousands of migrants who came from every state of the Mexican republic, attracted by the promise of a better-paid job, access to mortgage credit, and, in some cases, of its being a step-pingstone to migrate to the United States (Ampudia, 2009). The maquiladora export industry added to the labor force uninterruptedly between 1966 and 2000, when the number of those employed reached more than 260 000. This turned the city into an industrial enclave linked to the global economy through the hiring of people with low salaries and precarious jobs. Despite the profitability generated by this urban model, the city's development was not accompanied by an increase in infrastructure and equipment to address the needs of the population, bringing about important deficiencies in basic social services.

Also, the massive incorporation of women into this industry substantially modified the traditional roles of men and women, as well as the care of children. These changes explain in a certain manner the increase in violence toward women, whose most crude and extreme expression was the femicides, which brought a sad celebrity to this city beginning in 1993, when they began to be registered and publicly denounced (Monárrez, 2009). Beginning in 2001, the maquiladora export industry began a crisis phase whose most critical moment came in September 2009, when more than 75 000 workers lost their jobs as a result of the U.S. economic crisis. This produced an increase in the unemployment rate and in poverty, as well as more girls, boys, and youths dropping out of school and being placed in situations of risk.

If these structural conditions show the cost that the abandonment of the city has had, they still do not explain the resounding increase in the homicide rate and other indicators of violence beginning in 2008. This intensified through a series of situational factors: the presence of drug cartels disputing the strategic territory of the city for the trafficking of drugs to the United States, particularly between the Juárez and Sinaloa cartels, and the recruitment of young people by the gangs that formed the armed wings of the criminal organizations (Barrio Azteca, the Mexicles, and Artistas Asesinos). There was the implementation of the Operativo Conjunto Chihuahua (Joint Chihuahua Operation) and the Mérida Initiative, which resulted from an increase in human rights violations (Meyer, Brewer, and Cepeda, 2010), and the culture of impunity and silence that sends the message to society that anything is allowed (Cruz, 2011). All of the above have contributed to an increase in other kinds of violent acts on the community, family, and interpersonal levels that wind up being protected by the generalized impunity.

"SUBJECTIVITIES UNDER SIEGE": BETWEEN SYSTEMATIC VIOLENCE AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF AGENCY FROM ARTISTIC PRACTICES

In contexts of systematic violence, the feeling of fear and insecurity grows with many manifestations in a multifaceted way. Getting close to subjectivity is a way to learn how it is experienced and faced by subjects in their daily lives. In conceptual terms, violence can be defined as "the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation" (WHO, 2002:5).

This direct violence is the most visible, although it is closely linked with structural and symbolic violence (Galtung, 1996). The first corresponds to violence that comes from political and economic structures that produce and reproduce conditions of injustice, including social inequality and poverty, as mentioned in the previous section. For its part, symbolic violence encompasses those elements of the culture that legitimize or reinforce direct and/or structural violence through mechanisms of education, socialization, and media (Galtung, 1996).

In contrast to violence, fear corresponds to feelings "in the face of possible conduct or behavior that can assault or damage. Fear is an emotion caused by the awareness of a danger that threatens us" (Lindón, 2008:8). Violence and fear are only distinguishable analytically, as both are linked and feed on each other. The feeling of fear experienced in Ciudad Juárez has worsened the emptying of public life, expressed in self-imposed curfews, the abandonment of thousands of homes, the fear of public spaces, and the disruption of the energetic night life that characterized the city. In these years, fortress-like practices intensified, modifying daily life; the massive presence of walls, closed streets, barriers, security cameras, and guard posts turned Ciudad Juárez into a besieged city fragmented into a multiplicity of ghettos where withdrawal was highlighted as a way of protection (Padilla, 2013; Salazar and Curiel, 2012).

That is why systematic violence and fear are producers of a besieged subjectivity resulting from new forms of safeguards that have led the inhabitants of the city to withdrawal and isolation as a means of protection (Salazar and Curiel, 2012; Salazar, 2014). Besieged subjectivity reinforces the differences between the inside and outside, as well as between us and them. This translates into the identification of certain places—vacant lots, abandoned homes—as dangerous urban spaces that enable the walling up of personal space vis-à-vis common space and also in the building of a construct of the other, seeing the other as being the cause of the violence and fear; the other includes young people and the poor, just to give two examples.

Following the thought of Sherry Ortner, this work sees subjectivity as "the set of modes of perception, affect, thought, desire, fear, and so forth that animate acting subjects [like the set of] cultural and social formations that shape, organize, and provoke those 'structures of feeling' (Williams, 1977)" (Ortner, 2005:26). Thus, subjectivity is not reduced to individuals, but is historically situated and mediated through institutional processes and cultural forms that make possible both the reproduction of that social order and the potential of its being questioned and its eventual transformation by individuals.

This besieged subjectivity produces practices, representations, and constructs that guide the action of the subjects in a scenario in which violent death is present in daily life. It is a way to approach the "measures of perception and response with which social actors face the uncertainty of momentous risks" (Reguillo, 2007). There is a series of alternative social responses to fear besides putting up one's guard. This is the case of artistic practices that have the potential to break with a certain distribution of the sensible, making possible the emergence of other forms of being and feeling through reflection and questioning a given social order (Rancière, 2005). In contexts of violence, personal, ritual, or fictional expression of violent experiences can constitute a form of irruption of the established order, intervening in the ways in which forms of seeing, feeling, thinking, and doing are distributed. It is there where fear, silence, impunity, and lack of trust can reign; moving from the condition of victim to that of subject passes for the "manifest expression of experience and of being able to share it in a wide manner, which makes it possible to rebuild the political community" (Jimeno, 2008:262).

Taking into account the above, a qualitative focus was developed for the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the narratives and the artistic production of the young people who address the theme of violence in Ciudad Juárez through urban art. These narratives were pieced together through in-depth interviews and participant observation. The interviews explored how the young people conceived of themselves, how they perceive their life experiences, and what the margins of agency (and resistance) are from artistic practices in these urban spaces characterized by systematic violence and fear. The artistic production (silkscreens and murals) was recorded through photography during explorations of the city. The study sought to build "an ellipsis that maintains the tension between comparing, contrasting, and relating [in order to] access the connections between what is drawn, what was attempted to be drawn, and 'from where it was drawn'" (Scribano, 2013:65). For that an interpretation of the images was developed, considering their materiality, the image itself with its symbolic charge, and the context and the intent with which they were produced (Rose, 2012).

Through study and interpretation of these narratives and their artistic production, attempts were made to understand the intertwining of meaning in terms of the violence and violent death, and to find elements there that speak about social matters, placing special attention to the context of enunciation, the system of differential positions in which the subjects are situated, and the system of social representations of which they are carriers (Reguillo, 2000). The latter was contextualized through sociohistorical research and media analysis.

Although the study worked with a wide diversity of urban art collectives, this article focuses on the endeavors of the Rezizte collective. Its lengthy trajectory allows the clear observance of continuity and changes in the themes worked with and problematized artistically during the crisis of violence and insecurity the city experienced.

REZIZTE COLLECTIVE. "NEITHER FROM THE SOUTH NOR THE NORTH, ONLY FROM THE BORDER"

The Juárez poet Osvaldo Ogaz writes that the best definition of the Rezizte collective is that of Border Thinker, coined by Walter Mignolo: The border thinker

is that individual who is in the right place, in the middle ground, where he or she can walk in the opulence of the first world and arrive at the place where the third world lives, the border thinker places himself at the border to sidestep the cultural onslaught and stay in subalternity, living in that time and that space puts him at an advantage in the face of the multiculturalism he confronts ... rezizte shows us the true image, faithful to a city attacked on various flanks; it drags us toward its territory and carries us with its fight gloves to provide power to the people (Colectivo Rezizte, 2010).

Influenced by taggers and the murals of the cholos,2 as well as the graffiti of the 1980s and 1990s, characterized by the marking of territory in dispute between groups or neighborhoods, this collective, at first made up of design students at the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez, decided to meet to assert themselves outside the classroom setting. The initial goal was to participate in the debate over the sense and representation of the city through the exercise of social criticism. For this, they took up the most representative expressions of popular culture to communicate, express, and demonstrate the most strongly felt issues of the city through urban art, among them border identity, death, and violence, femicide, and the memory of slain young people.

A derivation of the translation of the English expression street art, urban art makes reference to art in the streets that uses graffiti, stencils, stickers, murals, and posters. It involves a strong interaction between the urban environment and artists, who through intervention in streets, plazas, and buildings seek to directly engage the observer through messages that produce meaning and affect power configurations through aesthetics and critical content, which drive other interpretations of what happens every day in the city. It has to do with images that carry, communicate, and reinforce social identities and activate their meaning in a complex relationship, linking those who produce the image, the image itself, and those who observe (Rose, 2012).

Rezizte, the name of the first campaign undertaken by the collective that then was called Máscara (Mask) 656, turned out to be so meaningful that in the end it became the name of the collective itself. This campaign sought to emphasize border identity using images, in stencils and stickers, of some of Ciudad Juárez's emblematic personalities such as Tin Tan. In the words of "Mamboska":

They acquired some pay phone cards with photographs of Tin Tan ... When I saw them, I said that this, for me, represents the border person, proud of his culture. Then I picked up the image separately as all this is part of the story of the cholos who are descendants of the pachucos ... and because of my admiration for Tin Tan, I said: I've got the image ... And the term Resiste was a homage I had made to a friend with a terminal illness ... Then later, I said: I see the city as being in agony, and look, it was the '90s, the end of the '90s ... I then saw that the city was in agony—although I did not think that the situation would become as bad as it did—and started using the term "Rezizte" (Mamboska, interview, 2013).

This campaign sought to establish anonymous contact with people who could identify with the image of the classic pachuco. Using the metaphor of a boxing match, to resist involves as much being on guard to attack as to defend oneself to withstand the opponent's blows. In the words of Yorch, also a member of the collective, "The word rezizte has a double meaning depending on its use—resisting in terms of withstanding or of opposing" (Yorch, interview, 2012).

Since then they have participated in exhibitions and in the creation of murals at national and international events. They also have held mural and silkscreen workshops for children and youths in their colonias (neighborhoods) and workshops for the recovery of public spaces with the Habitat program, sponsored by the federal government's Social Development Ministry (also known by its Spanish acronym Sedesol) and nongovernmental organizations. In addition to these activities, since 2004 (the first anniversary of Rezizte's founding) they held the binational festival Borde Manifiesta (Manifest Border), which brings together urban artists from Ciudad Juárez and El Paso with the goal of propagating the urban art that is created at this spot on the border. In 2008 and 2009, the festival could not be held due to a lack of funding, as well as the increase in violence, criminality, and repression against young people.

URBAN ART AS AN INCANTATION AGAINST SILENCE, FEAR, AND DEATH IN CIUDAD JUÁREZ

Like other young people in the city, the members of the Rezizte collective have faced multiple expressions of violence. In the interviews conducted with this group and other young people dedicated to urban art, allusion is made to various violent events that have marked the history of the city, including the constant presence of the femicide where victims have been schoolmates, acquaintances, neighbors, friends, and relatives. Nevertheless, between 2008 and 2012, the inhabitants of this border city, particularly the young men, have experienced unprecedented forms of violence. In the beginning it was not easy to talk about the violence that people had so recently experienced. With mourning still in process, and fear and wariness about speaking out concerning the issue, silence became a way to cope with what happened (Quiceno, 2008). Nevertheless, after a few months of fieldwork and the creation of an atmosphere of trust, a series of in-depth interviews was conducted. Seck, a member of the collective, told us:

There came a time when you asked whether or said that so-and-so or such and such was killed, and I often heard them say, "Well, that hasn't happened to me" ... and days, and years, passed—and then, many of those people who had said that, I heard them speak again [and] they did not repeat what they had said, instead saying, "It's a precarious time, it's that, yes, they killed my brother, they killed my cousin," and then we had the same feeling (Seck, interview, 2013).

The loss of colleagues, friends, neighbors, and acquaintances stopped being something exclusively experienced by the poor sectors of the city, extending to medical practitioners, university students, and others who for the first time experienced the violence in flesh and blood. In this context, uncertainty intensified, as did urban artists' fears that they might lose their lives while making one of their creations in a public space. For Yorch, feelings, themes, and forms of organization with other colleagues were uprooted:

Things changed ... a lot because this matter of working in the streets, right when they were being militarized, now one couldn't be in the street, or anywhere. There was the campaign for you not to go out and thus they had everything set up to exercise their authority. Then, little by little I begin to have this feeling of fear. I would drive with my paintings in my vehicle ... and [I was thinking] that if they pulled me over, they would not return my paintings, and would be asking me why I paint dead people. When I was painting, I felt the same way—would the military show up, or the others? There were all these feelings, but it also gives you the real reason to do it ... You are in a situation where you can say things, which none of us dared say; there was the possibility of doing it and giving people the impression of what was happening. When the military personnel arrived, it was useful to have a letter, even an invented one, with a signature and thus have something that vouched that there was permission, whatever. And I, well, I went out one time with the idea of staying out for a while, but then things did not work out so well, and I came back (Yorch, interview, 2012).

Beginning in 2008, the urban artists began to sense the fear circulating through and pervading the streets. This resulted in the forced migration of some of the members of the collective, such as Yorch. While he intended to leave the city, he quickly returned as a result of the need to be near his family and to continue working the border subject matter. Upon his return, he recognized the dilemma between keeping silent or expressing in some way what was happening. In this reflective process, if fear generates paralysis, it also is the motor that makes possible individual and collective action (Harkin, 2003). During this time of self-imposed curfews, Yorch worked on a series of images titled "El Sicario," made up of 13 silkscreen posters 22 inches wide and 33 inches tall, of which eight impressions were made. Some of them were placed on walls in various parts of the city (Pérez, 2015), which, despite all the time that had passed since 2009, have been respected by the different neighborhoods and crews that frequent the colonia, as well as those who live and work in these places. This series was done in silk-screen to be able to transport it easily to other cities to decry the situation the city was undergoing in those years. The series was done in black on white paper, as can be seen in Photo 1.

From the descriptive or denotative point of view, the protagonist is El Sicario, one of the most sinister and representative figures of the systematic violence that Ciudad Juárez and other places in Mexico and Latin America have been living through. He looks ahead, pointing a gun and occupying the entire surface of the silkscreen paper, establishing a direct relationship with the viewer facing him.

His face has no skin; it is a skull with a coup de grace bullet hole in the forehead, whose straight lines generate a feeling of hardness.

El Sicario not only is a character, but also has the job of committing murders for hire in exchange for financial compensation. Through this activity opponents are eliminated as part of the work of controlling markets, bolstering drug trafficking routes, and performing social cleansing. It is also an activity performed by boys and young men who have been recruited for the task; it reveals how death in Mexico has been turned into a commodity. The experience of the hit man is to live at the edge of existence, being one of the most fragile figures in a complex maze of social relationships, in which other actors intervene through the structure of organized crime.

El Sicario as an intimidating and fragile figure is represented by the face without skin with the bones exposed, evoking death. This is found present in a multiplicity of representations in public spaces, becoming a repertoire of expression of the multiple facets of femicidal and homicidal violence, both decrying and reinforcing it. It is found on walls, in the marches against femicide and violence, in the altars to the Santa Muerte (Saint Death), in the imagery of the Day of the Dead, on television, and in the sensationalist press. This emphasizes the intertextual character of the image, as the meaning of the image not only depends on this, but on the meanings evoked by other images in its materiality and memory (Rose, 2012).

At a connotative or interpretive level, it can be said that this series establishes a dialogue between the living and the dead. Putting oneself in front of the image is putting oneself in the place of the person who is going to die at the hands of the hit man. Perhaps because of this, the images transmit an intimidating feeling, invoking the fear of those living through this situation daily. Nevertheless, when the image of the skull appears with a bullet hole in it, the roles are reversed and the dead person is the hit man himself and not the person looking at him. In this way, the living and the dead observe each other and blur the limits between life and death itself. The person who kills is deader than the dead person, given that, as Yorch says, when they recruit a boy or a young man they seduce him with power and money, changing his life forever:

They tell a 15-year-old boy, "I'll give you 1,000 pesos right now and look at this at this and that, this is what it's about." It is likely that he has longed to have a gun, because he has seen everywhere he looks that this is what the most powerful have; he goes and does it and changes his life forever ... Killings and women (Yorch, interview, 2012).

With this reflection, Yorch emphasizes the complex reality of boys and young men who have found a place of belonging and power in being a hit man where one lives to kill and die in a world that does not offer him other possibilities. Asked about the skulls and skeletons in the series, he responds that all human beings have bones and that puts us in a place of equality. This evokes what Guadalupe Posada said: "Death is democratic, as in the end, blonde, brunette, dark-skinned, rich or poor, everyone winds up being a skeleton." (Turu, 2014). It's a little about this, of creating the connection through visual discourse with those who die and with those who kill, with an image that depersonalizes and universalizes to lead us to reflection about ourselves and to understand that all of us are human beings. In terms of the representation of death in popular culture and its relationship, the artist establishes a difference between natural and violent death:

Here he refers to a situation that often has to do with killings, of violence ... Well, I think I can resort to those elements—the person himself, or just the gun—to communicate all that happened in these four years ... That the Day of the Dead, having to do with the skeleton and the little sugar skulls, embodies a deepness that has more to do with old age and less to do with being killed (Yorch, interview, 2012).

As for the presence of death in narratives and in artistic production, it can be said that the relationship with death is not unique and is transformed in a permanent way. Although in Mexico there is a complex and rich repertoire of popular culture about death, in this context it acquires other meanings that pick up popular imagery, but also create new meanings that coalesce and mix together. Thanks to this shared repertoire, it was possible for the members of the collective to create these murals in broad daylight with the presence of the military in the streets.

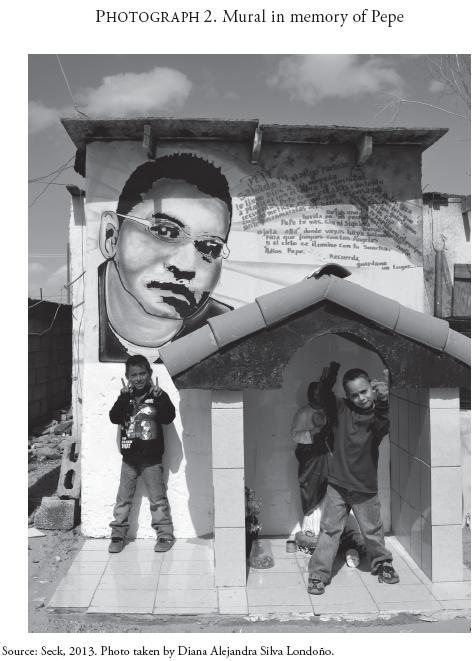

Other actions taken by the members of the collective are the murals in memory of, characteristic of the cholo groupings of young people (Valenzuela, 2012). They are murals that have a clear objective: to preserve the memory of dead friends and relatives of the colonia, as shown in Photo 2.

The mural in memory of Pepe was an initiative of his family. They asked Seck to create the work on one of the walls of the family's house in the Salvárcar neighborhood. Its placement in public space allows the memory of Pepe to transcend the private arena and be integrated into the landscape of the neighborhood. It remembers the son and friend happily, without making any reference in any way to his death and its causes. To see the mural you have to look up. At the foot of Pepe's image is an altar to Saint Jude Thaddeus, which is easily accessible.

There also are other murals in the neighborhood with positive images of those who have died in a violent way. While figures, statistics, and journalistic reports focus on the deaths of young people, blurring their identities and indiscriminately associating them with violence and crime, this demonization is counteracted in these murals through the assertion of the young person's name, face, and qualities. Even today, this resignification of violent death makes use of religious iconography aimed at subverting the common thinking that associates these deaths with the idea that they must have been up to something. This subversion of such thinking about death lets the family and loved ones cope with the stigma that comes with being a relative of a homicide victim. People walking the streets of the colonia sought out Seck and Yorch to ask them for new commemorative murals and T-shirts silkscreened with images of their relatives, showing the need to give meaning to death, to return to naming and humanizing the victims. According to Virgilio Elizondo (cited by Vila, 2007), remembering the dead prevents their dying completely:

The final, absolute, definitive death beyond which there is no earthly life left is when there is no one around to remember me or celebrate my life ... The pain which we experience when someone we know and love dies is transformed into an inner joy at the annual celebration of those who through death have entered ultimate life. Our memory of their lives becomes a source of life and energy.

CONCLUSIONS

The subjective experiences of systematic violence faced on a daily basis by young people dedicated to urban art in Ciudad Juárez are explored throughout this article. To do this, background was provided about some of the structural factors and circumstances that allow the understanding of the situation of systematic violence suffered in the border city. From these young people's point of view, their approach to the violence they had seen was a way to avoid the dominant rhetoric that defines them as the principal victims and victimizers; at the same time it shows that they are actors with the capacity of agency who can generate collective proposals to confront fear through art and cultural activities. It also is a way of understanding the tapestry of the meaning of life in the face of death that statistics are incapable of addressing. This provides an approach to the mechanisms of perception and response that explain how young people accommodate their strategies and cultural practices to confront acts of violence, as well as explain the active subject positions of those who have been directly or indirectly affected by violence.

In a context of systematic violence that produces a guarded society, these artistic practices lead to reflection about the implications of taking over public spaces as a political act. Through visual discourse, these practices allow the processing and communicating of tremendously painful and dehumanizing experiences— direct and indirect ones—that resignify the experiences and that generate alternative forms of communication countering the insistent politics of omission that come from the official discourse.

They are practices that show what is invisible and untold and at the same time are carriers of a meaning that is collectively activated in public spaces. Thus, they can eventually rupture the naturalized order of things that holds that each killing represents one less criminal and not a person missing from his family, his community, and society in general.

On the other hand, through these artistic practices the urban interventions of the young cholos were resignified, as in the case of the murals in memory of. In these murals the memory of the slain young people is recuperated and preserved; their names and faces had been invisibilized as a result of the constant presence of photographs of the thousands of bodies thrown on the public streets and the politics of wipe the slate clean and start over, promoted by the established order that sought to spread the idea that Ciudad Juárez was recovering and was returning to be the city of business.

In the face of the multiple attempts to conceal death on the part of authorities and businesspeople, the young people made death one of the most expressive elements of their lives. Through this visual discourse they evoke, convoke, dignify, and remember the dead, giving them faces, names, and color.

REFERENCES

Ampudia, Lourdes, 2009, "Empleo y estructura económica en el contexto de la crisis en Ciudad Juárez," in Laurencio Barraza, ed., Diagnóstico sobre la realidad social, económica y cultural de los entornos locales para el diseño de intervenciones en materia de prevención y erradicación de la violencia en la región norte: El caso de Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, Conavim/Segob, pp. 25-56. [ Links ]

Aziz Nassif, Alberto, 2012, "Violencia y destrucción en una periferia urbana: El caso de Ciudad Juárez, México," Gestión y Política Pública, Mexico City, CIDE, Special No. XXI, pp. 227-268. [ Links ]

Barraza, Laurencio, 2009, Diagnóstico sobre la realidad social, económica y cultural de los entornos locales para el diseño de intervenciones en materia de prevención y erradicación de la violencia en la región norte: El caso de Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, Conavim/Segob. [ Links ]

Blair, Elsa, 2004, Muertes violentas: La teatralización del exceso, Medellín, Instituto de Estudios Regionales-Universidad de Antioquia. [ Links ]

Colectivo Rezizte [digital publication], 2010, no title, Facebook, section "Información," Mexico, available at <http://www.facebook.com/pages/Colectivo-Rezizte/118847684850642?ref=ts&id=118847684850642&sk=info>, last accessed on March 20, 2012. [ Links ]

Consejo Ciudadano Para la Seguridad Pública y la Justicia Penal, 2013, "Ranking de las 50 ciudades más violentas del mundo," Seguridad, justicia y paz, available at <http://www.seguridadjusticiaypaz.org.mx/>, last accessed on February 1, 2014. [ Links ]

Cruz, Salvador, 2011, "Homicidio masculino en Ciudad Juárez. Costos de las masculinidades subordinadas," Frontera Norte, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, Vol. 23, No. 46, pp. 239-262. [ Links ]

Das, Veena, and Arthur Kleinman, 2000, "Introduction," in Veena Das, Arthur Kleinman, Mamphela Ramphele, and Pamela Reynolds, eds., Violence and Subjectivity, Los Angeles, University of California Press, pp. 1-18. [ Links ]

Galtung, Johan, 1996, Peace by Peaceful Means, London, Sage/PRIO. [ Links ]

Harkin, Michael E., 2003, "Feeling and Thinking in Memory and Forgetting: Toward an Ethnohistory of the Emotions," Ethnohistory, Durham, United States, Duke University Press, Vol. 50, No. 2, pp. 261-284. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI), 2013, "Estadísticas de mortalidad 1990-2012," Aguascalientes, Mexico, Inegi, available at <http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/registros/vitales/mortalidad/>, last accessed on March 15, 2014. [ Links ]

Jimeno, Myriam, 2008, "Lenguaje, subjetividad y experiencias de violencia," in Francisco Ortega, ed., Veena Das: Sujetos del dolor, agentes de dignidad, Bogotá, Universidad Nacional de Colombia/CES-Pontificia Universidad Javeriana/Instituto Pensar, pp. 261-291 (Colección Lecturas CES). [ Links ]

Jusidman, Clara, ed., 2007, La realidad social de Ciudad Juárez, Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

Lindón, Alicia, 2008, "Violencia/miedo, espacialidades y ciudad," Casa del Tiempo, Mexico City, UAM, Vol. 4, pp. 8-14. [ Links ]

Mamboska[interview], 2013, by Diana Silva, "Nos rebelamos a la muerte, participación juvenil contra la militarización y la violencia," Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, Programa DSD SSRC-IDRC-OSF-Uniandes. [ Links ]

Meyer, Maureen; Stephanie Brewer, and Carlos Cepeda, 2010, Abuso y miedo en Ciudad Juárez: Un análisis de violaciones a los derechos humanos cometidas por militares en México, Washington, D.C./Mexico City, WOLA-Centro Prodh. [ Links ]

Monárrez Fragoso, Julia, 2009, Trama de una injusticia: Feminicidio sexual sistémico en Ciudad Juárez, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte/Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

Orquiz, Martín, 2013, "Cimbran a Juárez 25 masacres en cinco años," El Diario de Juárez, in section "Local", Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, Publicaciones e Impresos Paso del Norte, available at <http://diario.mx/Local/2013-09-24_cc3b99cc/cimbran-a-juarez-25-masacres-en-cinco-anos/>, last accessed on September 24, 2013. [ Links ]

Ortner, Sherry, 2005, "Geertz, subjetividad y conciencia posmoderna," Etnografías Contemporáneas, Buenos Aires, Universidad Nacional de San Martín, No. 1, April, pp. 25-54. [ Links ]

Padilla, Héctor, 2013, "Ciudad Juárez: Militarización, discursos y paisajes," in Salvador Cruz, ed., Vida, muerte y resistencia en Ciudad Juárez. Una aproximación desde la violencia, el género y la cultura, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, pp. 105-141. [ Links ]

Pérez, Jorge, 2015, Yorch artista urbano/muralista/serigrafista, Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, available at <http://yorchperez.com/galeria.html>, last accessed on April 10, 2011. [ Links ]

Quiceno toro, Natalia, 2008, "Puesta en escena, silencios y momentos del testimonio. El trabajo de campo en contextos de violencia," Estudios Políticos, Colombia, IEPRI-Universidad Nacional de Colombia, No. 33, July-December, pp. 181-208. [ Links ]

Quintana S., Víctor M., 2010, "Modelo juvenicida," La Jornada, in section "Opinión," available at <http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2010/02/05/index.php?section=opinion&article=017a2pol>, last accessed on February 5, 2012. [ Links ]

Rancière, Jacques, 2005, Sobre políticas estéticas, Barcelona, Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona/Servei de Publicacions-Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona. [ Links ]

Reguillo, Rossana [dossier], 2000, "Anclajes y mediaciones del sentido. Lo subjetivo y el orden del discurso: Un debate cualitativo," Revista Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Universidad de Guadalajara, No. 17, Winter 1999-2000, available at <http://www.cge.udg.mx/revistaudg/rug17/4anclajes.html>, last accessed on February 3, 2014. [ Links ]

Reguillo, Rossana, 2007, "Subjetividad sitiada. Hacia una antropología de las pasiones contemporáneas," E-misférica, Instituto Hemisférico de Performance y Política, Vol. 4, No. 1, available at <http://hemi.nyu.edu/hemi/es/e-misferica-41/199-e41-essay-subjetividad-sitiada-hacia-una-antropologia-de-las-pasiones-contemporaneas>, last accessed on October 16, 2013. [ Links ]

Rose, Gillian, 2012, Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, Thousand Oaks, United States, Sage. [ Links ]

Salazar Gutiérrez, Salvador, 2014, "Systemic Violence, Subjectivity of Risk, and Protective Sociality in the Context of a Border City: Ciudad Juarez, Mexico," Frontera Norte, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, Vol. 26, No. 51, January-June, pp. 137-156. [ Links ]

Salazar, Salvador, and Martha Mónica Curiel, 2012, Ciudad abatida: Antropología de la(s) fatalidad(es), Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

Scribano, Adrián [electronic book], 2013, Encuentros creativos expresivos: Una metodología para estudiar sensibilidades, Buenos Aires, Estudios Sociológicos Editora. [ Links ]

Seck [interview], 2013, by Diana Silva, "Nos rebelamos a la muerte, participación juvenil contra la militarización y la violencia", Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, Programa DSD SSRC-IDRC-OSF-Uniandes. [ Links ]

Turu, Pilar [digital publication], 2014, "Origen e historia de La Catrina," Cultura colectiva, available at <http://culturacolectiva.com/origen-e-historia-de-la-catrina/>, last accessed on October 16, 2014. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, José Manuel, 1988, ¡A la brava ése!: Cholos, punks, chavos banda, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, José Manuel, 2012, Nosotros. Arte, cultura e identidad en la frontera México-Estados Unidos, Mexico City, Conaculta. [ Links ]

Vila, Pablo, 2007, Identidades fronterizas. Narrativas de religión, género y clase en la frontera México-Estados Unidos, Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, El Colegio de Chihuahua/Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

World Health Organization (WHO), 2002, Informe mundial sobre la violencia y la salud: Resumen, Washington, D.C., WHO. [ Links ]

Yorch [interview], 2012, by Diana Silva, "Nos rebelamos a la muerte, participación juvenil contra la militarización y la violencia," Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, Programa DSD SSRC-IDRC-OSF-Uniandes. [ Links ]

* Text and quotations originally written in Spanish.

** Becaria del Programa de Becas Posdoctorales en la UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, UNAM. El trabajo de campo para esta investigación se ha realizado gracias a una beca de investigación del programa Drogas, Seguridad y Democracia, financiado por el Social Science Research Council, Open Society Foundations, International Development Research Centre y la Universidad de los Andes.

1 Ciudad Juárez ranks among the 50 most violent cities in the world, although it stopped being the most violent in 2011. That year it dropped to second place; it fell to 19th in 2012 and 37th in 2013. (Consejo Ciudadano para la Seguridad Pública y la Justicia Penal, 2013) [Citizens Council for Public Safety and Criminal Justice].

2 Cultural expression emerged at the end of the 1970s along the Mexico-U.S. border as a form of resistance in the face of exclusion and racism experienced by Mexicans and Mexican-Americans (Valenzuela, 1988).