Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicación y sociedad

versión impresa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.18 Guadalajara 2021 Epub 04-Oct-2021

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2021.7820

General theme

Youth sound consumption practices, between big platforms and the radio ecosystem: the case of Colombia-Spain

1 Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, España. maria.gutierrez@uab.cat

2 Universidad de Nebrija, España. andresbarriosrubio.abr@gmail.com

This paper presents an analysis and correlation of youthful sound consumption practices from the comparative specificities of Colombian and Spanish university ecosystems. Through a quantitative-qualitative methodology applied to a sample of 160 subjects, a generational cut pattern is confirmed both in the use of devices and in the type of content demanded. Likewise, the emergence of a hybrid consumer in whose digital sonosphere contents from global platforms, radio and podcasts coexist, and who is interested in the offer of the own radio ecosystem is outlined.

Keywords: Sound consumption; young people; smartphone; podcast; radio

Este artículo presenta un análisis y correlación de las prácticas juveniles de consumo sonoro desde las especificidades comparativas de los ecosistemas universitarios colombianos y españoles. Mediante una metodología cuantitativa-cualitativa aplicada a una muestra de 160 sujetos, se confirma un patrón de corte generacional tanto en el uso de dispositivos como en el tipo de contenido demandado. Asimismo, se perfila la irrupción de un consumidor híbrido en cuya sonoesfera digital conviven contenidos procedentes de plataformas globales, radiofónicas y podcasts, e interesado por la oferta del ecosistema radiofónico propio.

Palabras clave: Consumo sonoro; jóvenes; smartphone; podcast; radio

Introduction

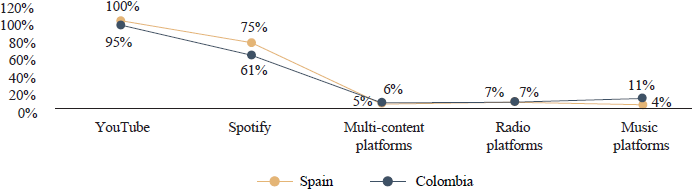

The irruption of the Internet (Figure 1) gave users the capacity to decide what to consume and when and where to consume it. This broke the paradigm that dominated to that moment the relationships between the radio industry and its audience (Barrios-Rubio & Gutiérrez-García, 2017; Vázquez Herrero & López García, 2019). In fact, the audience modified its sound consumption routines (Herrera-Damas & Ferreras-Rodríguez, 2015; Monclús et al., 2015), to the point in which it eliminated the idea of “prime time” (Castells in Torras i Segura, 2017, p. 117). In addition, the digital migration process led the industry to explore new production (Martínez-Costa et al., 2012) and distribution strategies (Cerezo, 2018; Ortiz & López, 2011) that focused on the population’s younger sectors (Gutiérrez et al., 2014; López Vidales et al., 2014). This target market was especially attracted to the new portable devices that facilitated creating personal sound content playlists, among other things (Bull, 2010; Canavilhas, 2009).

Source: The authors with Hootsuit data (2020a, 2020b).

Figure 1 Digital globalization in Colombia-Spain

Understanding the peculiarities of an ecosystem’s consumption habits was key for the sound industry (Cavia-Fraile, 2016). In the case of Colombia and Spain (Figure 1), it was observed that Colombians are more active in the online environment, while Spaniards show a higher Internet penetration level. Now, smartphones are fundamental in both cases. In fact, the volume of subscriptions to mobile phones is greater than the number of inhabitants: 116% in Colombia and 117% in Spain. In this way, smartphones have become the access road to social media -91% Colombia and 98% Spain- and, especially for young people, multimedia streaming or podcast products (Pedrero-Esteban et al., 2019; Ruiz del Olmo & Belmonte Jiménez, 2014). In this context, the competitiveness index for the radio industry increased when alternative proposals managed by new actors appeared, while content distribution became diluted (Marta-Lazo et al., 2016). Therefore, strategies to increase synergy between offline and online environments were designed (Cea, 2019) in order to strengthen brands in the digital sonosphere3 (Barbeito & Fajula, 2009; Barrios-Rubio, 2020; Perona-Páez et al., 2014) of an every increasingly hybrid audience (Videla-Rodríguez & Piñeiro-Otero, 2017). The audience was beginning to combine music distribution services -Spotify, iTunes, YouTube and others- with podcast platforms -iVoox, Cuando, Podium Podcast and others- (Moreno-Cazalla, 2018) and radio content.

Operators have bet on developing brand applications in order to facilitate access, playlist creation and other services (Castells et al., 2006; Mihailidis, 2014; Piñeiro-Otero, 2012; Ribes et al., 2017). In parallel, digital audio consumption time has increased (IAB Spain, 2020) alongside the volume of “first mobile” and “only mobile” users (ComScore, 2018). For this type of user, listening involves an intimate and personal experience, not only because they can decide what to listen to, but because using earphones submerges them in their own universe of sound, shutting out the outside world (Berry, 2016). This circumstance strengthens emotional ties and loyalty to services (Ruiz del Olmo & Belmonte Jiménez, 2014).

The universe of sound of young people

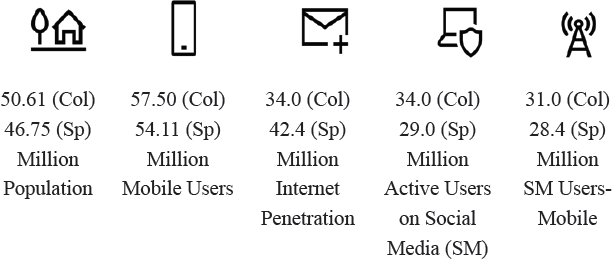

For all that, the digital receipt and consumption environment from mobile devices (Díaz-Nosty, 2017) has promoted, on one hand, disseminating radio applications (Moreno et al., 2017) and, on the other hand, scattering users’ attention (Llorca-Abad, 2015) from using various screen simultaneously (Figure 2). To face these challenges, some authors indicate that radio brands must promote sound literacy (Pérez-Maíllo et al., 2018), allow their own forums to create digital communities (García-Avilés et al., 2016; García-Jiménez et al., 2018; Gutiérrez-García & Barrios-Rubio, 2019; Ribes et al., 2017; Videla-Rodríguez & Piñeiro-Otero, 2013) and promote personal experiences (Bonini & Monclús, 2015; Gerlich et al., 2015). That is to say, the focus of attention must be the audience and content, not just aspects related to technology.

Source: The authors with Hootsuit data (2020a, 2020b).

Figure 2 Access to digital content in Colombia-Spain

Young people are without a doubt the best examples of new media practices. With respect to audio, multiplatform consumption that combines streaming, podcasts, social media and conventional antennas can be observed (Pedrero-Esteban et al., 2019), always according to people’s interests and expectations (Castells et al., 2006). From the perspective of the digital ecosystem (Figure 2), a higher degree of sound component appropriation was observed in the practices of Colombians, with a divergence from podcasts.

Consumption habits are linked to mobile phones (García-Jiménez et al., 2018) and adapt to their technical constraints and purchased data packages (Ruiz del Olmo & Belmonte Jiménez, 2014). Young multiplatform consumers build their own particular digital sonosphere with offline and online content from international platforms and platforms from their close environment (Videla-Rodríguez & Piñeiro-Otero, 2017), such as conventional radio brands and/or native digital brands.

Music consumption is the best example. Although access to Spotify is a widespread practice (López Vidales, et al., 2014; Perona-Páez et al., 2014; Torras i Segura, 2017), this does not mean radio music has been abandoned (Gutiérrez et al., 2011), since it maintains significant listening rates (Audio Today, 2019).

Assuming the role of smartphones in consumption practices, the drawn profile may lead to thinking the universe of sound of young people is defined based on music content from platforms and/or thematic radio stations. But, to what point can it be confirmed that they are not interested in non-musical sound content? Answering this question and its derivatives is this article’s objective. The paper presents a comparative study between Colombian and Spanish young people based on the case study.4

Methodology

A quantitative-qualitative methodological instrument5 was designed to answer the research questions and show trends in the habits of young multiplatform consumers with respect to sound content. It is not only about defining their digital sonosphere, which is basically dominated by music, but also covering the type of non-musical audio productions they access and the devices from which they do so. Following the provisions of McDaniel and Gates (2009), a structured survey made of five blocks, with a total of 26 questions and a margin of error no greater than 3%, was developed. It allows characterizing a study group and defining consumption habits (Table 1).

Table 1 Survey structure

| Blocks | Required Information | Study Factor |

| Sociodemographic Data | Age and gender | Particular features of the subject and their capacity to access the technological universe |

| Audio Equipment | Access to and use of sound consumption devices | Connection particularities and device appropriation |

| Sound Content Consumption | Type, access, place of consumption, applications and prescription | Features of approaching access platforms and the sound product |

| Podcast Consumption | Downloading habits, origin and frequency | Digital sound products with spoken content downloaded for timeless consumption |

| Radio Consumption | Synchronous and/ or asynchronous and prescription | The relationship between young people and the radio industry with antennas and the digital ecosystem |

Source: The authors.

The instrument was validated previously by completing 100 surveys, 50 at each school participating in the research, in order to be able to standardize the coding (Wimmer & Dominick, 1996), review confusing parameters and determine the overlap range (Holsti, 1969). Variable cross-tabulation has allowed establishing a behavioral pattern (Bernal, 2006) for users in the sound environment from a comprehensive approach to the studied reality (García, 2009). The following research questions have been established based on the premise that young people are a hybrid, multiplatform-consuming audience:

RQ1. Is the relationship between the subject, the sound content and the access device determined by their belonging to a particular radio ecosystem?

RQ2. What is the link between the triangulation of sound-platform-smartphone content in young people’s consumption agenda?

RQ3. Is generalist content part of young people’s diet in terms of sound, podcast and radio consumption?

The corpus of study consists on a random sample of 1606 young people between the ages of 18 and 20, completing their communications degrees, distributed equally between Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano (Utadeo-Colombia) and Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (UAB-Spain).7 The study’s focus was selected by two relevant factors: the equivalence of the Colombian and Spanish radio biosphere, with the presence of Prisa Radio as a leading company in the sector in both countries, and the relevance and proximity of students to technology, communication media and productive routines, as they were being prepared to work professionally in said sector. Understanding that the sample is not representative, it has been considered sufficient for comparative analysis in an exploratory study that pays special attention to detecting similarities and differences between the selected groups of people and their geographic spaces (Figures 1 and 2). From this perspective, it is worth noting that radio penetration is higher in Colombia (86%) than in Spain (59%). The same applies to the penetration of downloading music applications (Colombia 69% and Spain 53%) and using voice to search for data in the digital environment (Colombia 44% and Spain 35%) (Hootsuit, 2020a, 2020b).

Results

A multi-device sound consumer

The data shows that smartphones are the preferred device when consuming sound content (95.5% of all surveyed people), although they are followed closely by personal computers (89.5%) and television (77%). A generational multi-device consumption practice is therefore indicated, in which online and, to a lesser degree, analogue content coexist. This is a consequence of the low use of, among others, radio receivers (30%), even though 66% of surveyed Spaniards and 56% of surveyed Colombians stated they had said devices. A similar situation was detected regarding music equipment, which was seldom used for consuming music (39.5% of all surveyed people), although 77.7% of UAB students and 54.3% of Utadeo students stated they at least had one at home.

This behavior seems to follow similar patterns: the user makes a selection in light of expectations and circumstances revolving around the action of receiving sound. In this way, it is observed that smartphone use is greater at home (69% of the sample) than in cars (48.3%). The factor that determines selection may be control over the expense of mobile data when consumption occurs in a space without WiFi. However, this premise loses value when smartphones and public transportation are associated (56.6%). These vehicles generally do not have free access to the Internet, but smartphones are used more than in private transportation.

From a geographic perspective, Spanish young people have shown a higher predisposition to using smartphones in private transportation (62.5% of the total) than Colombians (37.5%). It could be inferred that the latter tend to turn on the radio. However, the data also shows low radio use (20.5% Utadeo; 23.8% UAB). Among the surveyed, 98.7% have stated they consume sound content, in which music was the first option (93.8% of all surveyed people), followed at a distance by information (72.8%) and entertainment (39.5%). Of all the highlighted differences between both sound ecosystems, the most relevant difference was humor (Figure 3), which was higher among UAB students (47%) than Utadeo students (27%). A surprising datum is that 1.3% described them as not being sound consumers despite recognizing they listen to music.

*Percentage of total from own ecosystem.

Source: The authors.

Figure 3 Sound content consumed by Spanish and Colombian young people

The fact that consuming humorous content is significantly high among the students surveyed from UAB can partly be a consequence of the penetration of a program the leading radio station in the region presents. It generates a large volume of downloads through its app and website. This circumstance is not comparable in Colombia.

When it comes to music content consumption, its association with smartphones was validated (Perona-Páez et al., 2014; Pedrero-Esteban et al., 2019, among others). Now, computers and television sets are also considered music players (Figure 4) with significant differences if each ecosystem’s particularities are regarded. In this way, Colombian young people seem more prone to using big screens (15%) and computers (10%) than Spaniards. The latter, however, relevantly tend to use audio equipment (20%).

*Percentage of total musical content consumers.

Source: The authors.

Figure 4 The devices young people use to listen to music

When it comes to young people consuming music, the radio still awakens interest as a device (Figure 4), more frequently among Utadeo young people than UAB (7%). From the perspective of spaces in which the radio may be tuned (house, vehicle and public transportation), the percentages for homes are significant: 93.1% Utadeo compared to 88% UAB. For the latter, they listen more to the radio in cars (84%) than in public transportation (72%). This position is inverted in the case of Colombia, where young people have stated they consume radio more on public transportation (79.3%) that in private (62%). While using radio devices goes beyond their conception as music reception devices, it can be noted that using them implies consumption simultaneously with antenna broadcasting, which, in light of the data, is preferred at home.

Sound consumption agenda on mobile phones

Musical content applications for smartphones are downloaded the most, although they are not the only ones (Figure 5). Before delving into this matter, it is worth nothing that 30.9% of all surveyed people have stated they only had music apps on their mobile phones. Attending to the geographic factor, the percentage is higher in Colombia (32.1%) than in Spain (29.6%). These indices show the interest for sound consumption that is not exclusively musical.

Of the 96.2% of UAB young people with downloaded musical apps, 53.9% also have them for entertainment, 37.2% have informational apps, and 21.8% have sports apps. Of the 83.7% of Utadeo young people with musical apps, 38.3% also had informative apps, 30.9% had entertainment apps and 19.1% had sports apps. From a global perspective, the volume of students with a more varied offer of content on their mobile device corresponds to UAB (12%). Independent from the percentages between both groups, a different ranking of interest can be observed between information and entertainment, although both have coincided in placing sports in third place.

It must be highlighted that the survey had a wide array of non-musical content options. In this area, Colombians have demonstrated greater interest for that type of preference. The language learning category was ranked first (17.6% Colombian compared to 6.4% Spanish), followed by audiobooks (11.8% compared to 3.8%) and general interest (5.9% compared to 1.2%). The exception is represented by fiction. For this content, those surveyed from UAB outweighed students from Utadeo (8.9% compared to 4.4%, respectively). Said interest was also validated in the sphere of apps, since those focused on this type of content were among people’s favorites.

Another interesting piece of data was the low volume of young users in both ecosystems with a minimum of four app downloads, combining musical and non-musical content consumption. Only 9.2% of those surveyed from UAB installed an entertainment, information and sports application in combination with a music application. Only 4.4% of those from Utadeo stated likewise. Although downloading music apps is a general practice, a significantly low percentage stated they did not have any, but did have other types of content. This circumstance has been observed in both ecosystems (6% of Colombian users and 3% of Spanish users). An approximation to their profile allows observing that young people from Utadeo presented more heterogeneous behavior than those from UAB. While the former diversely combined all kinds of apps except music ones, the latter coincided with only information, sports and entertainment.

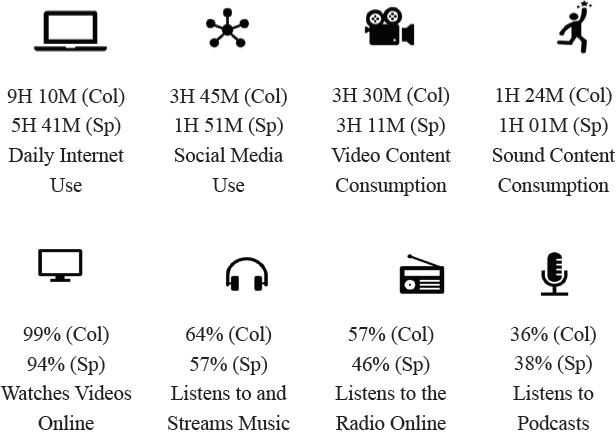

Based on the premise that the types of downloaded applications mark consumption, students were asked what sound content platforms they used at least once a week. As expected, YouTube, followed at a distance by Spotify, led the list (Figure 6). For most surveyed students, the YouTube platform provides online sound content, although its catalogue mostly consists of audiovisual production. Intuitively, it could be determined that young people tend to consume music through this social network. However, the spectrum of audiovisual content and genres is so wide that they probably also access entertainment, general interest and other channels. In fact, the radio industry has fostered its presence in this network by placing cameras in stations. This decision corroborates the consolidation of new consumption habits. It is important to highlight that access to YouTube does not necessarily imply that the consumed content is only musical. The case of Spotify, which, until now, has been considered the quintessential music platform, is different. However, at the time this article was written, it already had an extensive catalogue of podcasts.

The apparent contradiction between what types of platforms were downloaded on smartphones and which ones were used during the week indicate that students in the academia and the radio industry give one same thing different names. Otherwise, the disparity between these results and the indices mentioned in previous paragraphs referring to non-musical content applications could not be understood. It is also observed that, independent from the nuances the percentages could introduce in each ecosystem, we may be before a generational undertaking that prioritizes products, surely consumed in conjunction with other tasks, above the platform that gave them access. In light of this data, young people seem to have appropriated technology, adapting it to their circumstances. In this way, for example, a platform such as YouTube, which provides audiovisual content, is turned into an online radio on demand by basically taking advantage of its sound dimension (Torras i Segura, 2017).

Access to content from different devices also implies a wider exposure to prescription. Despite this, young people seem to believe they are the ones choosing songs (Gendrau, 2013). In this research, 57% of young people from UAB and 43% of young people from Utadeo stated they did not follow any recommendations despite significant consumption through YouTube and Spotify. Instead, they consider friends and media the main prescribers, followed at a distance by social media (Figure 7), where YouTube leads the Colombian and Spanish ranking.

Podcasts in the sound diet of young people

Over one third of those surveyed stated they commonly consumed podcasts. Colombians had higher percentage (39.4%) than Spaniards (30.8%). With respect to their origin (Figure 8), independent platforms are the main providers. Once again, Utadeo reached a higher percentage (25%) than UAB (15%). However, upon delving into each ecosystem, global practices have been observed, such as concurrence in ranking YouTube and Spotify as favorites, although Soundcloud, iVoox, Apple Music and iTunes are also named as sound content providers.

*Percentage of those who define themselves as consumers.

Source: The authors.

Figure 8 Podcast origin

From a comparative perspective, radio podcasts are the priority among those surveyed at UAB, while podcasts on independent platforms stand out among Utadeo students. Taking into account that the penetration index of the radio is higher in Colombia than in Spain, the existence of a more consolidated sound culture can be inferred among Colombian young people, which leads them to explore content away from the radio. Instead, the practices defined by UAB students show the extent of radio consumption compared to the online environment and, perhaps, low interest in discovering native content online.

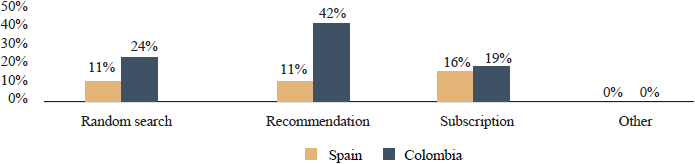

Recommendations are undoubtedly the best way to discover a podcast, according to Utadeo students (Figure 9). Random searches and subscriptions are left far behind. The latter involves a level of loyalty that both radio brands and platforms desire. Although it seems to work among students from UAB, the percentage is scarcely relevant enough to consider it a common practice. In fact, this content is preferably listened to at home, independent from the device they use. This datum allows understanding the frequency of downloads, whether that is basically weekly or scarcely daily (5% in Spain and 4% in Colombia).

*Percentage of those who define themselves as consumers.

Source: The authors.

Figure 9 How young people access podcast content

Consuming radio podcasts, in most cases, also involves being a listener. This specific case has been observed among Spanish young people (68% of all podcast consumers) and Colombian young people (65.6%). One interesting fact is that podcast consumers define themselves as radio listeners, both simultaneously and asynchronously. They mostly use radio devices, smartphones and computers. To a lesser degree, some stated they use radio apps.

Young people and the radio

Out of those surveyed, 63.4% considered themselves radio listeners. In other words, they listen to content produced by the radio industry. The percentage difference between ecosystems is irrelevant: Colombian young people reached 64% and Spanish young people reached 63%. Even though the traditional device is most commonly used, smartphones reached significant levels in both ecosystems (Figure 10). In fact, 38.5% of young people from Utadeo defined themselves as listeners and 25.5% of those from UAB students stated they do not use the conventional device. Instead, they use mobile phones and computers, demonstrating a migration towards digital devices.

*Percentage of those who define themselves as radio listeners.

Source: The authors.

Figure 10 Devices used to consume radio content

These results undoubtedly reaffirm the combination of simultaneous and asynchronous listening, although the latter is limited. An important factor connected to consumption is portability and access to media from digital devices. These elements are associated to the cost they imply for the studied population. The research indicates that listening to the radio is linked to a family listening tradition transmitted from one generation to the next.

Conclusions

Young people are the users that have contributed the most to configuring new behavioral dynamics and online and offline media use by seeking to satisfy their needs for entertainment and information. It is worth highlighting that their condition as communications students has not revealed significant data with respect to those obtained in other sound reception studies among young people.

The relevance of the Internet in young people’s media diets and the preeminence of virtual platforms and apps that facilitate watching and listening to all types of content through streaming can be deduced from the most significant mobile device penetration in Colombia and Spain (Figures 1 and 2). From this, the existence of generational practices that are replicated in different ecosystems and allow identifying the profile of a young universal sound consumer with particularities that mostly originated from the sound culture of the ecosystem to which they belong can be inferred. In this way, this research has detected a greater interest in podcasts from Colombian young people, as well as content from the radio industry.

Digital multi-device sound consumption seems to have ousted traditional radio and record players in both ecosystems. Although smartphones are the main device, and understanding that portability is one of its most appreciated characteristics, digital sound reception mostly occurs at home. This circumstance allows understanding why content downloading is insignificant, although the cost of data according to model and cost can also influence it.

Despite this, brand loyalty managed through subscriptions demonstrated similar features between the surveyed students. It is difficult to say what factors may explain said circumstance, since aspects such as the penetration of the habit of combining simultaneous and asynchronous listening is still low. This situation contrasts with the fact that smartphones continue being the device of preference, even for radio reception.

Other elements connected to daily life, such as urban infrastructure and public and/or private transportation are also factors to be taken into account when determining a usage pattern and practices to interconnect the content proposed by the radio industry itself and independent platforms.

From the perspective of the relationship with the radio, it can be stated that subjects consciously or unconsciously seek to both satisfy personal needs and ask questions and find answers through a way of seeing and feeling society. The truth is that the lack of content adjusted to this target market’s interests has influenced distancing from the radio. It will recover by understanding the role of smartphones in daily life and urgently strengthening sound literacy.

In addition, the research shows there is no unification of concepts used by users, the industry and academia to refer to digital communication elements and content that circulates in the Internet. However, based on the convergence of factors we can state that there is a tradition of sound in social, media, in-person and virtual relationships that lead the public to synchronous and asynchronous consumption from an extensive array of sound content. Although young people consumption habits have displaced traditional media, the fact remains that the role of the family has been important for their awakening to sound.

The presented data demonstrates the need to face consumption practice analyses differently, especially among young people, since decisions that will mark the immediate future in terms of developing a universe of sound in all of its complexity will be drawn from their conclusions. Associating habits with a space that is strategically delimited by geography and/or a sound market is fundamental in order to establish specific behavioral patterns, because globalization only confers general principles.

REFERENCES

Audio Today. (17 de junio de 2019). How America listens. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/report/2019/audio-today-2019/ [ Links ]

Barbeito, M. L. & Fajula, A. (2009). La sono-esfera digital como nuevo entorno creativo. En F. García (Ed.), Actas del I Congreso Internacional Ciudades Creativas (pp. 577-591). Icono 14. [ Links ]

Barrios-Rubio, A. (2020). R@dio en la sonoesfera digital. Alpha Editorial. [ Links ]

Barrios-Rubio, A. & Gutiérrez-García, M. (2017). Reconfiguración de las dinámicas de la industria radiofónica colombiana en el ecosistema digital. Cuadernos.Info, 41, 227-243. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.41.1146 [ Links ]

Bernal, C. A. (2006). Metodología de la Investigación para Administración, Economía, Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales. Pearson. [ Links ]

Berry, R. (2016). Podcasting: Considering the evolution of the medium and its association with the word “radio”. The Radio Journal. International Studies in Broadcast & Audio Media, 14(1), 7-22. https://doi.org/10.1386/rjao.14.1.7_1 [ Links ]

Bonini, T. & Monclús, B. (Eds.) (2015). Radio Audiences and Participation in the Age of Network Society. Routledge. [ Links ]

Bull, M. (2010). iPod: un mundo sonoro personalizado para sus consumidores. Comunicar, XVII(34), 55-63. https://doi.org/10.3916/C34-2010-02-05 [ Links ]

Canavilhas, J. (2009). Contenidos informativos para móviles: estudio de aplicaciones para iPhone. Textual & Visual Media, 2, 61-80. http://www.bocc.ubi.pt/pag/canavilhas-joao-contenidos-informativos-para-moviles.pdf [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2009). Comunicación y poder. Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Castells, M., Fernández-Ardèvol, M., Qiu, J. L. & Sey, A. (2006). Mobile Communication and Society: A Global Perspective. MIT Press. [ Links ]

Cavia-Fraile, S. (2016). New Radio Model in the Fourth Screen: Radiovision, The Radio That You Can Watch. Fonseca, Journal of Communication, 13, 65-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.14201/fjc2016136584 [ Links ]

Cea, N. (2019). Periodismo y Redes Sociales: análisis de las estrategias de difusión de los periódicos digitales. En V. A. Martínez-Fernández, X. López-García, F. Campos-Freire, X. Rúas Araujo, O. Juanatey-Boga & I. Puentes-Rivera (Coords.), Más allá de la innovación. El ecosistema de la comunicación desde la iniciativa privada y el servicio audiovisual público (pp. 193-202). Media XXI. [ Links ]

Cerezo, P. (2018). Los medios líquidos. La transformación de los modelos de negocio. UOC. [ Links ]

ComScore. (2018). Futuro digital global. https://www.comscore.com/lat/Prensa-y-Eventos/Presentaciones-y-libros-blancos/2018/Futuro-Digital-Global-2018 [ Links ]

Díaz-Nosty, B. (2017). Coexistencia generacional de diferentes practicas de comunicación. En B. Díaz-Nosty (Coord.), Diez años que cambiaron los medios: 2007-2017 (pp. 7-26). Ariel. [ Links ]

García-Avilés, J. A., Martínez-Costa, M. P. & Sádaba, C. (2016). Luces y sombras sobre la innovación en los medios españoles. En C. Sádaba, J. A. García-Avilés & M. P. Martínez-Costa (Coords.), Innovación y desarrollo de los cibermedios en España (pp. 265-298). Eunsa. [ Links ]

García-Jiménez, A., Tur-Viñes, V. & Pastor-Ruiz, Y. (2018). Consumo mediático de adolescentes y jóvenes. Noticias, contenidos audiovisuales y medición de audiencias. Icono 14, 16(1), 22-46. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v16i1.1101 [ Links ]

García, J. A. (2009). La comunicación ante la convergencia digital: algunas fortalezas y debilidades. Signo y Pensamiento, XXVIII(54), 102-113. https://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index.php/signoypensamiento/article/view/4529 [ Links ]

Gendrau, L. (2013). Joves, de comunicació i consum cultural. Treballs de Sociolingüística Catalana, 22, 179-188. http://revistes.iec.cat/index.php/TSC/article/viewArticle/58195 [ Links ]

Gerlich, N., Drumheller, K., Babb, J. & D’Armond, D. (2015). App Consumption: An exploratory Analysis of the uses & gratifications of mobile Apps. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 19(1), 69-79. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/amsjvol19no12015.pdf [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, M., Monclús, B. & Martí, J. M. (2014). Radio y jóvenes, una encrucijada de intereses y expectativas. En A. Huertas-Bailén & M. Figueras-Maz (Eds.), Audiencias juveniles y cultura digital (pp. 107-123). Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, M. Ribes, X. & Monclús, B. (2011). La audiencia juvenil y el acceso a la radio musical de antena convencional a través de internet. Communication & Society, XXIV(2), 305-331. https://revistas.unav.edu/index.php/communication-and-society/article/view/36208 [ Links ]

Gutiérrez-García, M., & Barrios-Rubio, A. (2019). Del offline a la r@dio: las experiencias de la industria radiofónica española y colombiana. Revista de Comunicación, 18(1), 73-94. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC18.1-2019-A4 [ Links ]

Herrera-Damas, S. & Ferreras-Rodríguez, E. M. (2015). Mobile apps of Spanish talk radio stations. Analysis of ser, Radio Nacional, cope and Onda Cero’s proposals. El Profesional de la Información, 24(3), 274-281. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2015.may.07 [ Links ]

Holsti, O. (1969). Content analysis in communication research. Free Press. [ Links ]

Hootsuite. (12 de febrero de 2020a). Digital 2020: Spain. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-spain [ Links ]

Hootsuite. (17 de febrero de 2020b). Digital 2020 Colombia. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-colombia [ Links ]

IAB Spain. (12 de febrero de 2020). Estudio anual de Audio Online 2020. https://iabspain.es/estudio/estudio-audio-online-2020/ [ Links ]

Jansen, H. (2012). La lógica de la investigación por encuesta cualitativa y su posición en el campo de los métodos de investigación social. Paradigmas, 4, 39-72. [ Links ]

Llorca-Abad, G. (2015). La capacidad de atención y el consumo transmedia. Obra digital: Revista de Comunicación, 8, 136-154. https://www.raco.cat/index.php/ObraDigital/article/view/301179 [ Links ]

López Vidales, N., Gómez Rubio, L. & Redondo García, M. (2014). La radio de las nuevas generaciones de jóvenes españoles: Hacia un consumo on line de música y entretenimiento. ZER. Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 19(37), 45-64. https://ojs.ehu.eus/index.php/Zer/article/view/13516 [ Links ]

Marta-Lazo, C., Ortiz, M. A. & Martín, D. (2016). La información en radio. Contexto, géneros, formatos y realización. Editorial Fragua. [ Links ]

Martínez-Costa, M. P., Moreno, E. & Amoedo, A. (2012). La radio generalista en la red: un nuevo modelo para la radio tradicional. Anagramas, 10(20), 165-180. https://doi.org/10.22395/angr.v10n20a11 [ Links ]

McDaniel, C. & Gates, R. (2009). Investigación de Mercados Contemporánea. Internacional. [ Links ]

Mihailidis, P. (2014). A tethered generation: Exploring the role of mobile phones in the daily life of young people. Mobile Media & Communication, 2(1), 58-72. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2050157913505558 [ Links ]

Monclús, B., Gutiérrez, M., Ribes, X., Ferrer, I. & Martí, J. M. (2015). Radio Audiences and Participation in the Age of Network Society. En T. Bonini & B. Monclús (Eds.), Listeners, Social Networks and the construction of Talk Radio Information’s discourse (pp. 91-115). Routledge. [ Links ]

Moreno, E., Amoedo, A. & Martinez-Costa, M. P. (2017). Usos y preferencias del consumo de radio y audio online en Espana: tendencias y desafios para atender a los publicos de internet. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodistico, 23(2), 1319-1336. http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/ESMP.58047 [ Links ]

Moreno-Cazalla, L. (2018). La Radio Online en Espana ante la convergencia mediatica: sintonizando con un nuevo ecosistema digital y una audiencia hiperconectada (Tesis doctoral inédita). Universidad Complutense de Madrid. https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/49995/ [ Links ]

Ortiz, M. A. & López, N. (Eds.). (2011). Radio 3.0. una nueva radio para una nueva era. La democratización de los contenidos. Fragua. [ Links ]

Pedrero-Esteban, L. M., Barrios-Rubio, A. & Medina-Ávila, V. (2019). Adolescentes, smartphones y consumo de audio digital en la era de Spotify. Comunicar, 60, 103-112. https://doi.org/10.3916/C602019-10 [ Links ]

Pérez-Maíllo, A., Sánchez Serrano, C. & Pedrero-Estebán, L. M. (2018). Viaje al Centro de la Radio. Diseño de una experiencia de alfabetización transmedia para promover la cultura radiofónica entre los jóvenes. Comunicación y Sociedad, (33), 171-201. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v0i33.7031 [ Links ]

Perona-Páez, J. J., Barbeito-Veloso, M. & Fajula-Payet, A. (2014). Young people in the digital sonosphere: media digital, media devices and audio consumption habits. Communication & Society, 27(1), 205-224. https://revistas.unav.edu/index.php/communica-tion-and-society/article/view/36011 [ Links ]

Pineiro-Otero, T. (2012). Radios corporativas online. La aventura de las marcas en la radiodifusion sonora. Opcion, 32(12), 281-300. https://www.produccioncientificaluz.org/index.php/opcion/article/view/22048 [ Links ]

Redacción PRnoticias. (23 de abril de 2019). ‘La vida moderna’ abandona su calvario y crece un 25% en 2019. Prnoticias.com. https://prnoticias.com/2019/04/23/la-vida-moderna-calvario-crece-egm/ [ Links ]

Ribes, X., Monclús, B., Gutiérrez-García, M. & Martí, J. M. (2017). Aplicaciones móviles radiofónicas: adaptando las especificidades de los dispositivos avanzados a la distribución de los contenidos sonoros. Revista de la Asociación Española de Investigación de la Comunicación, 4(7), 29-39. https://doi.org/10.24137/raeic.4.7.5 [ Links ]

Ruiz del Olmo, F. J. & Belmonte Jiménez, A. M. (2014). Los jóvenes como usuarios de aplicaciones de marca en dispositivos móviles. Comunicar, 43, 73-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-07 [ Links ]

Torras i Segura, D. (2017). ¿Nueva escucha en la red? Hábitos universitarios de consumo musical y navegación. Anàlisi. Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura, 57, 115-130. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/analisi.3092 [ Links ]

Vázquez Herrero, J. & López García, X. (2019). La renovación de formatos en el contexto multimedia. En V. A. Martínez-Fernández, X. López-García, F. Campos-Freire, X. Rúas Araujo, O. Juanatey-Boga & I. Puentes-Rivera (Coords.), Más allá de la innovación. El ecosistema de la comunicación desde la iniciativa privada y el servicio audiovisual público (pp. 19-30). Media XXI. [ Links ]

Videla-Rodríguez, J. J. & Piñeiro-Otero, T. (2013). La radio móvil en España. Tendencias actuales en las apps para dispositivos móviles. Palabra Clave, 16(1), 129-153. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2013.16.1.5 [ Links ]

Videla-Rodríguez, J. J. & Piñeiro-Otero, T. (2017). La radio online y offline desde la perspectiva de sus oyentes-usuarios. Hacia un consumo híbrido. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 23(2), 1437-1455 https://doi.org/10.5209/ESMP.58054 [ Links ]

Wimmer, R. & Dominick, J. (1996). La investigación científica de los medios de comunicación. Una introducción a sus métodos. Bosch. [ Links ]

How to cite:

Gutiérrez-García, M. & Barrios-Rubio, A. (2021). Young people sound consumption practices, between big platforms and the radio ecosystem: the case of Colombia-Spain. Comunicación y Sociedad, e7820. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2021.7820

3The digital sonosphere is the convergence of channels and platforms to which a listener/user has access from display devices and from which new consumption habits, direct or timeless, can be delineated. A new appropriation of media and content.

5The survey was conceived as a quantitative instrument that allows performing qualitative approximations to the study population using open coding questions that provide descriptive inputs for one-dimensional, multi-dimensional and explanatory analyses that indicate the diversity of the studied phenomenon (Jansen, 2012).

6The sample is not representative, but it is considered sufficient for exploratory analysis because it is equivalent to 20% of the selected population at the two studied institutions.

Received: May 21, 2020; Accepted: October 02, 2020; Published: March 10, 2021

texto en

texto en