Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicación y sociedad

versión impresa ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.19 Guadalajara 2022 Epub 03-Oct-2022

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.8191

Articles

Medios de comunicación y compromiso político

The app ecosystem in the 2020 US election: information or politainment1

2 Universidad de Valladolid, España. alicia.gil@uva.es

3 Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, España. nuria.navarro.sierra@urjc.es

4 Universidad de Valladolid, España. cristina.sanjose@uva.es

5 Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, España. carolina.herranz@urjc.es

This article analyzes the contribution of mobile device applications to political discourse in the US presidential election between Joe Biden and Donald Trump in 2020. The sample consisted of 101 applications (apps) and the analysis was based on a qualitative methodology that examined the popularity and discourse features of these apps. The results reflect a wide range of developments that oscillate between commercial interest and a form of blurred political engagement located somewhere across entertainment, parody and virality.

Keywords: Election campaigns; mobile applications; politainment; United States

Este artículo analiza la contribución al discurso político de las aplicaciones desarrolladas para dispositivos móviles en el contexto de las elecciones presidenciales estadounidenses que enfrentaron a Joe Biden y Donald Trump en 2020. La muestra comprende 101 aplicaciones y su análisis se fundamenta en una metodología cualitativa que analizó la popularidad y los rasgos del discurso de estas apps. Los resultados reflejan un amplio registro de desarrollos que pivotan entre el interés comercial y un compromiso político difuminado entre el entretenimiento, lo paródico y la viralidad.

Palabras clave: Campañas electorales; aplicaciones móviles; politainment; Estados Unidos

Este artigo analisa a contribuição para o discurso político de aplicativos desenvolvidos para dispositivos móveis no contexto das eleições presidenciais dos EUA que enfrentaram Joe Biden e Donald Trump em 2020. A amostra compreende 101 aplicativos e sua análise é baseada em uma metodologia qualitativa que analisou a popularidade e características de fala desses aplicativos. Os resultados refletem uma ampla gama de desenvolvimentos que giram entre o interesse comercial e um compromisso político indistinto entre entretenimento, paródia e viralidade.

Palavras-chave: Campanhas eleitorais; aplicativos móveis; politainment; Estados Unidos

Introduction

There is nothing new about the fact that the reach of mobile technology has widely permeated into many aspects of everyday life. The cultural, symbolic, and social interaction that this new scenario has brought about is an object of academic interest in a large number of disciplines (Segado-Boj et al., 2022) and organizations “to create and boost content through new applications that foster communication” (Puebla & Farfán, 2018, p. 114). Political communication has not been impervious to this situation, and mobile devices have led to new creation, consumption, and interaction dynamics along the lines of political infotainment, which affect the agent that creates such content, the content itself, and its impact on audiences (Berrocal et al., 2013; Boukes, 2019). Specifically, politainment refers to a specific combination “which comprehends popular culture as a forum for political insight and activity, such that popular genres of entertainment can also function as sources for political knowledge, value orientation, and civic engagement” (Riegert & Collins, 2016, p. 2). This suggestive approach has given rise to controversies that have been reviewed in the light of traditional audiovisual media and have identified hedonic, escapist, eudaemonic, and truth-seeking lines of consumption (Bartsch & Schneider, 2014; Holbert et al., 2014). Considering the technological changes described above, some of the classic premises of political communication have been transformed in terms of context innovation and mutation. Their main forms of expression are based around three elements: politainment, Twitter, and the social audience (Zamora-Martínez & González-Neira, 2022, p. 23).

The genesis of this phenomenon lies in the spectacularization of political information through television (Berrocal & Cebrián, 2009), which is constructed by means of style-based features that have been clearly defined in other studies (Zamora-Martínez & González-Neira, 2022, pp. 24-25). The field of study of politainment is almost exclusively centered on the dominant forms of audiovisual media in society and is therefore limited. However, focusing only on these media would obscure the real scope of the issue as it would prevent the assessment of the full influence of entertainment in politics (Holbert et al., 2014).

The dissemination of politainment-related content has increased through the use of social networking sites. While the most popular site is Twitter (e.g., Claes & Deltell, 2015), other more recent networks such as TikTok are also used for this purpose (Cervi et al., 2021). Their popularity has been analyzed in terms of how it can boost political discourse and as a means to reinforce the traditional campaign (Abuín-Vences & García-Rosales, 2020). Its main driver, however, is the social audience as a creative audience (Castells, 2009), as it provides immediate clues for examining the social reception of political messages and flows (González-Neira & Quintas-Froufe, 2014). Moreover, the popularity of political infotainment in the electoral campaigns of those countries in which the two-party system is in crisis has resulted in innovative political organizations being created (Pacheco-Barrio, 2022).

This is a recent scenario that has been continuously updated as a consequence of the technological development of the new dynamics of audiovisual consumption. It has had an impact on the emergence, dissemination, and popularity of political content on YouTube (Berrocal et al., 2017), the growing political personalization in social media (Gil-Ramírez et al., 2019), online infotainment (Berrocal et al., 2013), the use of gaming content (Neys & Jansz, 2010), the rise of memes (Zamora Medina et al., 2021) and, in recent years, the specific popularity of infotainment in the mobile device ecosystem (Gómez-García et al., 2019).

Within this new area of study, interactive and networking technologies have become increasingly popular, which suggests a democratization of the social framework in which knowledge is generated and perceived, the power structures in everyday life, and the degree of civic and political engagement (Glas et al., 2019; Gómez-García et al., 2021). In every election campaign, “politics, seemingly inherently grave, necessitates its antithetical, those genre forms that might come across as more playful” (Serazio, 2018, p. 134).

This spectacularization of government activity has also been transferred to the ecosystem of applications developed for mobile devices (henceforth, apps) based around specific political leaders (Kleina, 2020; Navarro-Sierra & Quevedo-Redondo, 2020; Quevedo-Redondo et al., 2021) and the use of apps by political parties (Zamora-Medina et al., 2020). In this scenario, the new content distribution platforms converge with politainment in electoral campaigns. It is worth identifying their involvement and penetration in America and other areas, as some studies have recently noted (Gómez-García et al., 2019).

The purpose of this study is to identify the uses, strategies and implications of politainment in this new scenario, by addressing the following research questions:

RQ1. What was the impact of apps and the mobile ecosystem on a major political event such as the 2020 US election?

RQ2. What kind of message do the most downloaded apps convey about the candidates for President of the United States (Donald Trump and Joe Biden), and what are the main features of their discourse?

The study therefore has a twofold objective. It provides an approach to one of the less visible aspects of recent electoral campaigns which, due to its novelty and uniqueness, has received preliminary but not consistent academic attention (Johnson et al., 2021). It also seeks to meet the current methodological challenge posed by research on mobile apps (Light et al., 2016) and develops some analytical elements to help understand their contribution to the political message in an electoral context.

Material and methods

The sample was identified and selected based on criteria used in previous research (Gil-Torres et al., 2020; Gómez-García et al., 2019). In this case, apps were selected from searches in the two main app distribution platforms on Android (Google Play) and iOS (Apple Store). The search was completed using SensorTower, an app monitoring tool that collects a large, variable number of all apps located on Google Play and Apple Store. Their respective search engines were used in relation to the terms: “Biden”, “Election 2020”, “USA, campaign”, “Trump”, “Kamala Harris”, “Mike Pence” and some variants that were combined with basic Boolean operators. This exploration was complemented by snowball sampling through suggestions provided by the platforms themselves based on the first results (Baltar & Brunet, 2012). This process yielded all the apps related to the electoral process in the United States from January 2nd to November 3rd, 2020. Once the search results were screened and duplicates removed, the final sample was made up of 101 applications. Apps developed before the election year were included if they had been updated after November 2018, when the US midterms were held, and the election race was already focused on the presidential election.

Using the sample, a list was compiled with all the information provided by both platforms (Google Play and Apple Store). Among other data, information was recorded on each developer, operating system, number of downloads, date of creation and/or update, and whether they were fee-paying, free, or monetized content (and how they did so). Subsequently, each of the apps was coded using quantitative content analysis parameters. The variables came from an earlier study and were complemented by deductively identified new codes that were obtained through a procedure theoretically akin to Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). In this way, repetitions were observed in the discourse of some of these apps, which were included in the coding in the form of the following variables:

The apps’ purpose was classified according to previous theoretical frameworks on the creation of online political content (Gómez-García et al., 2019; Neys & Jansz, 2010). After examining the contents of the app, four main purposes were identified: informative (seeking to provide information linked to the elections and/or one ofthe candidates); persuasive (seeking to express an opinion, participate in public debate or generate a climate of opinion in relation to the election and/or the candidates); mobilizing (identifying an interest in promoting a specific action in relation to the US election); and entertaining (merely seeking entertainment, unrelated to an informative or ideological construction).

The tone of the apps and their type of discourse was classified according to the categorization developed in earlier research (Gómez-García et al., 2019): escapist (with no link to electoral reality, offering an unreal or merely viral construction); expository (providing information related to the candidate or aspects of the election); intentional (showing an opinion or being deliberately associated with “something”); satirical (underlining emotional elements with an ironic purpose); and circumstantial (resorting to the popularity of the character, but without proposing a complementary construction).

Some contradictions were identified in the section on the categorization of the apps made by the developers, as they did not match the content found in the exploratory phase of the research. Therefore, the authors conducted a new coding process. A new review of the apps was carried out to establish themes for each one and to determine who or what their focus was. Finally, the apps were classified into five large groups that sought to identify their potential for framing political discourse (Ballesteros-Herencia & Gómez-García, 2020): information, candidate support, content creation (stickers, memes, countdown...), games, and campaign simulators and results.

The focus was defined according to the most important aspect of the app. The following variables were therefore considered: candidate, campaign and strategy, election, voting and results, and clickbait.

The modes of discourse were classified into three categories created for this study: elaborate, simple, and reproduced discourse. “Elaborate discourse” was found in those apps that included some kind of new content or underlying information that had been further developed, in a production process that clearly involved care and effort. “Simple discourse” comprised those apps constructed in an expository, simple, unsophisticated discourse that sometimes boiled down to a widget or an image of the candidates. Finally, “reproduced discourse” referred to a mere collection of information that appears in other sources, where apps are only a means to access them (Zamora-Medina et al., 2020, p. 7).

The reliability of the coding for the four variables above was checked using Krippendorff’s (2013) alpha through the analysis of nominal values in the ReCal3 tool. The coding process was carried out by the authors of this article on 30% of the sample. It was ensured that the coders could work independently to check the reliability of the content and that they apply the same instructions for the same content (Krippendorf, 2004). This process was employed for each of the four variables to reinforce the integrity of the process (Riffe et al., 2019, pp. 114-115). The values obtained were 0.78 for the first variable, 0.74 for the second, 0.79 for the third and 0.91 for the fourth. Reliability was found to be appropriate for each case.

Results

The impact of the apps generated in the 2020 elections

The 101 apps that dealt with the US presidential election between Joe Biden and Donald Trump attest to its popularity as a political phenomenon. Other events or political leaders analyzed previously have not seen such a high level of interest (Gómez-García, et al., 2019; Navarro-Sierra & Quevedo-Redondo, 2020), although on the occasion of the previous election held in the United States between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton more than 300 apps were developed, even more than those in this study (McCabe & Nelson, 2016).

The development of apps for the 2020 US election was unevenly distributed across the major mobile operating systems. While 36 of the 101 apps were on Android, 65 were released on the Apple Store. However, 12 were developed for both operating systems, which reduced Android’s share to 23.76% of the total, and therefore iOS accounted for more than half of the sample (52.47%). This data is of interest because it represents a new tendency, as the Android operating system was found to be dominant in previous research into this type of content, as it was lax in screening for access to published content (Gil-Torres et al., 2020). In the United States, Apple’s operating system holds 60.29% of the mobile device market share (Statcounter, 2021). The changes in the number of apps studied suggest that we may be witnessing a change in the trend among developers, who create them for the dominant operating systems of the countries where they want to market them, in order to increase downloads and any hypothetical monetization.

However, it is difficult to measure the popularity and/or reception of this content, especially when there is no way of knowing the number of downloads from the Apple Store platform. As indicated in the methodology, this study approximated their hypothetical “popularity” by using the available download data (Table 1) but could only assess the download data for the apps available on Google Play on the Android operating system (36).

Table 1 App downloads (Android O.S.)

| Download range | Number of apps (sum of apps) |

% of the sample (sum%) |

| 0-100 | 19 (19) | 53% (53%) |

| 101-500 | 5 (24) | 14% (67%) |

| 501-1 000 | 1 (25) | 3% (70%) |

| 1 001-5 000 | 3 (28) | 8% (78%) |

| 5 001-10 000 | 2 (30) | 5% (83%) |

| More than 10 000 | 4 (34) | 11% (94%) |

| More than 50 000 | 2 (36) | 6% (100%) |

Source: The authors.

The largest number of apps distributed on Android did not exceed 100 downloads (18.81%), but others reached higher figures; eight exceeded 5 000 downloads and two surpassed half a million: a campaign simulator game entitled 270 | Two Seventy US Election (Political Games LLC, 2017) and Official Trump 2020 App (Donald J. Trump For President, 2016), the official app of Trump’s campaign. Their leading position in download numbers may be linked to the fact that they were created for the 2016 and 2018 elections, although both were reused and updated a few days before the 2020 vote. Persistence over time was a significant factor in stark contrast to other research that underlined the topicality and transience of many of the apps that are developed for these purposes. Others (such as those mentioned above) were more based on a sense of persistence and on updating both informative and entertaining content related to cyclical political events.

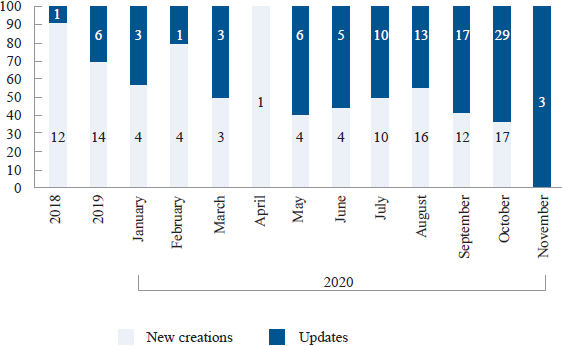

Figure 1 shows that 75 new apps were developed over the course of 2020 and were permeated by the topicality that marked the election, as 44.55% (45) of the apps developed for both platforms in that year were launched in the three months leading up to voting day. The Democratic and Republican conventions were held in August, and 61.38% (62) of the apps were updated from that month onward, a sign of the discourse dynamics inherent in this type of content.

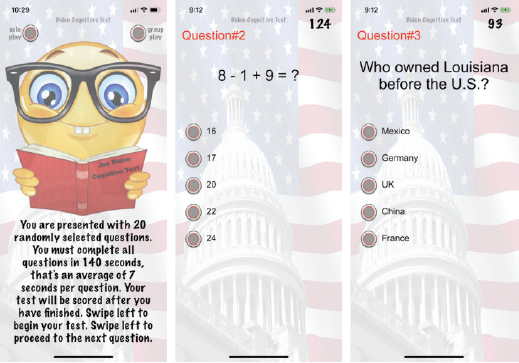

The names of the different apps had similar features in order to attract the attention of potential users. Firstly, 45 apps contained a reference to the year 2020 in their name as a way of asserting that they were current. Secondly, 42 of the total 101 included a direct reference to one or to both candidates. Specifically, 28 referred to Biden and 20 to Trump. However, this did not imply that there was a direct relationship between the title and the content; and on six occasions, clickbait apps were found that used the name of politicians as an appeal mechanism but had nothing to do with the 2020 US presidential election. For example, Biden Cognitive Test (The Global App Company, 2020) contained a set of miscellaneous questions and answers that had nothing to do with the candidate.

Purpose and tone of the apps’ discourse

The involvement of apps in the political discourse of the 2020 US election was based on a number of variables which are outlined below. The categories selected by the developers themselves to consolidate the discourse of their creations were the first point of interest in order to find any underlying purposes and study the tone of the discourse used. The analysis in the following section was complemented by the themes and key elements.

Categories

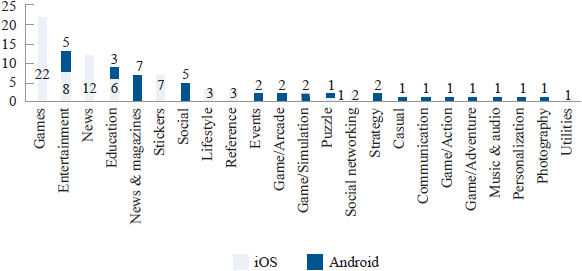

The thematic focus of the political discourse proposed by the developers was analyzed on the basis of different assumptions. The first of these took into account the categories in which the different apps were included in the Apple Store and Google Play content distribution platforms. Out of the 27 categories available in the Apple Store, there was substantial content related to “Games”, with 20.79% (22), followed by “News”, with 11.88% (12) and “Entertainment”, with 7.92% (8). Within the 32 existing content sections in Google Play, categories were more spread out, and none of them contained even ten apps. “Information and Magazines” had the highest percentage, 7% (7). Therefore, although it is difficult to give an idea of how the contents were developed on Google Play, there was clearly infotainment and political content in the iOS apps.

The context for this data can be found in the overall percentages for both platforms (Figure 3). In this case, the highest percentages were in the categories of “Games” (iOS) or “Games/Arcade/Action/Adventure/ Simulation” and “Entertainment” (Android). However, these data must be qualified based on the analysis of each of the apps. Out of fifteen sticker and emoticon apps, only seven had been classified by the developers according to their category; the rest labelled them in other categories such as “Lifestyle”.

Purpose

The coding of the implicit purpose of the apps showed that almost 50% of them (46.5%) were games aimed at entertaining their users. These data are similar to what other studies have found in similar campaign contexts (Gómez-García et al., 2019; Kleina, 2020) and underlines the imprint that politainment has on the mobile app ecosystem.

However, the rest of the categories showed significant diversification. The objective of informing on the electoral process was particularly remarkable in this group, as there were 21 apps (20.79%), including Brink Election Guide (DBK Ventures, Inc., 2020), which offered services such as voter registration information, mapping of voting locations in any state, and help in handling early or mail voting applications. It also provided resources for people with disabilities to ensure that their rights were not violated.

Apps aimed at mobilizing (18, 17.82%) or persuading (15, 14.85%) users accounted for almost a third of the total sample. This may point to a greater engagement by developers, who sought to promote a specific action in the electoral process, or took advantage of the app to express an opinion, raise public debate or generate a particular climate of opinion on specific issues. These two purposes together came together in Team Joe App (Biden for President, 2020), an organizing tool which, in addition to providing campaign updates, enabled users to give information about friends or family members for Biden’s team to contact them and collect data about these potential voters. They also allowed users to send text messages to friends and candidates, ask questions to third parties, or become campaign volunteers.

A similar discourse was followed by AAPIs for Biden (Kepler Base LLC, 2020), shown in Figure 5, the only app detected in the study that was created by a group that defined itself as “Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders”. Their app was a grassroots tool that centralized donations, volunteering (phone calls, for example) and latest news updates.

These two apps generated around Biden were created by PACs (Political Action Committees, private organizations that campaign for a candidate without being contractually linked to them). However, no apps were identified for Trump’s campaign that brought together these two purposes other than his official campaign app.

Tone of speech

The study was completed by analyzing the two previous variables using one of the dominant narratives in each of the sample applications (Figure 6). This showed that apps with intentional discourse (33.66%) were the most common. This usually consisted of persuasive discourse about the merits (or shortcomings) of one of the candidates. This set included, in addition to the obvious ones such as the candidates’ own campaign apps, those that “helped” to elect candidates based on affinity with stated policies such as ActiVote (ActiVote Inc, 2019). This discourse was complemented by satirical discourse around the candidates (5% of the total apps). This took shape through various purposes: persuasive, to ridicule Trump and his actions (Trump Train - Road To White House, Long Shot, 2020), expressive (Mike Pence Fly, ADVERGAMES INC, 2020) and entertaining/gaming (The Presidential Debate Game, John Geras, 2020).

A total of 28 apps contained an expository narrative in line with the theme or data presented (27.72%). The main feature of the apps included in this variable was that their discourse offered information related to the candidate, the election, or the polls. This sometimes overlapped with the informative purpose discussed above, which can be clearly seen in Electoral Map Presidential 2020 (Slabs Dev, 2020) and Brink Election Guide (DBK Ventures, Inc., 20209). But this was not always the case. The purpose behind 2020 Election Countdown (Heuristo, 2018) was to mobilize, but the tone was informative, as it was a “countdown” to report the results of election day; whereas Campaign 20/20 (George Sinfield, 2019) was a game that simulated all the elections from 1960 to 2020 and contained informative content but was intended to be entertaining.

Source: Electoral Map Presidential 2020 (Slabs Dev, 2020) and Brink Election Guide (DBK Ventures, Inc., 2020).

Figure 7 Electoral Map Presidential 2020 and Brink Election Guide

This set of discourses was completed by circumstantial (18%) and escapist (16%) apps. Both showed the popularity of a series of apps that merely used the popularity of the characters for the creation of memes, such as Election memes (Adam Wilkie, 2016), and a fictional reality that portrayed a supplementary construction of the election process, such as Election Fight 2020 (12 to 6 Studios LLC, 2017), a fighting game between the two candidates running for election.

Themes, focuses and modes of discourse

Thematic families

The themes are framed in the context of the electoral process (Figure 8). The first element that stood out in this process is that, while only 22 apps were categorized as “Games” by their creators, 32 (31.68%) were found that met the criteria to be included under this heading. The next major block was content creation (stickers, memes or countdowns), which amounted to a quarter of all apps (25.74%). The sum of both themes exceeded half of the sample (57.42%) and highlighted the gaming or entertaining goal of the content displayed, which they shared with other contents on social networking sites (Zamora et al., 2021).

Lagging somewhat behind were apps that displayed data, news, or any other type of information, including those supporting candidates, which barely amounted to 12% of the total (11.88%). These narratives were the least attractive, as they were even outperformed by the 19 (18.81%) campaign or voting center result simulators such as 2020 Electoral Map, Presidential (Slabs Dev, 2020), which surpassed 1 000 downloads, or Campaign Manager - An Election Simulator (RosiMosi LLC, 2020), an advanced election simulation model that uses real-world election data, population demographics, and historical voting trends that attracted over 5 000 downloads in the first weeks after its release.

Focus themes

The focused themes showed which elements of the election campaign were prioritized in each of the apps’ narratives (Figure 9). The largest group referred to candidates (39, 38.61%). This subset was divided into two main groups. Those that markedly personalized Trump or Biden as the key figures of the action that took place within the app were in the majority (24). They were normally games, such as Knock Trump Out 2020 Election (Daniel Sillers, 2018), where only action available to the player was to punch a virtual representation of Trump until he was knocked out; or apps intended to mock the candidates. Most of them were creations for the dissemination of potentially viral content such as Biden Soundboard - Human Gaffe Machine! (Rawsome Studios, 2020), which collected the presidential candidate’s misspeaking, rambling, baffling, and gaffes during his historical political career.

The second set of apps focused on promotional tools (15) with the aim of “selling” the image of the candidate, without any additional features, as in the case of Animated Biden and Harris 2020 (Nguyen Hoang, 2020), which disseminated emoticons of the Democratic candidates.

These apps that identified the two presidential candidates included eleven “banal” applications that offered emoticons for mobile devices, photo frames or controversial tweets in the case of Trump. The nine “trumpmoji” apps were all very similar to each other. There were twelve trivial apps that used Biden as a theme, emoticons and sounds being the most common; however, there were some frivolous ones such as Biden Celebration (The Global App Company, 2020), where the player had to explode the balloons that fell from the sky with cannon shots to get the thirteen US flags in front of the White House.

There were seven pre-2020 Trump-themed apps that had been updated them for the 2020 election. One of these was 2020 Election - Donald Trump Photo Frames (Figure 10), which attracted between 1 001 and 5 000 downloads and was created at the end of 2019, heading into the election year. There were only two pre-election related to Joe Biden, which were updated in the summer of 2020.

Source: 2020 Election - Donald Trump Photo Frames (Photo Frame Download, 2020).

Figure 10 2020 Election - Donald Trump Photo Frames

Those apps that focused on campaigning and election strategy also had a very strong presence (31, 30.69%), with campaign simulators being in the majority (9) along with apps created to campaign for candidates in the general election (8) or in the Democratic primaries (3), albeit not necessarily officially. These included four aimed at generating a community around Biden or Trump, such as Donald Trump 2020 (Hii5 Media, 2020), with more than 10 000 downloads. These were aimed at mobilizing users and were created as a form of social network targeting candidates’ followers with functions such as live chats, forums, social videos, questionnaires, etc. There were seven tools for users to create their profiles as voters and to publicize or evaluate political proposals, including the aforementioned ActiVote (ActiVote Inc, 2019) and The Election (JC Nichols LLC, 2020), a quiz that proposed voting for one candidate or another depending on the policies that the user preferred.

The election as a political process, voting, and election results made up the next set of interest and consisted of 20 apps out of 101 in the sample (19.80%). The most numerous were voting simulators and result predictors (9 in total) such as 2020 Election Spinner Poll (Get A Charge LLC, 2016). This app moved between gamification and simulation, as it recorded the virtual votes that the user cast for the candidates each day and added them to those of other participants to show the weekly support for each politician.

Debate is the most interesting and most popular campaign element (Gentzkow, 2006) in an election. The first election debate held in September 2020 was watched by 73.1 million viewers on a television channel (Nielsen, 2020). However, debates did not garner the same interest from developers in the mobile ecosystem, as only two apps included them. These were an informative app which, interestingly, was created one day after the first debate, Biden and Trump’s debate 2020 presidential debates (Daymood, 2020) and The Presidential Debate Game (John Geras, 2020).

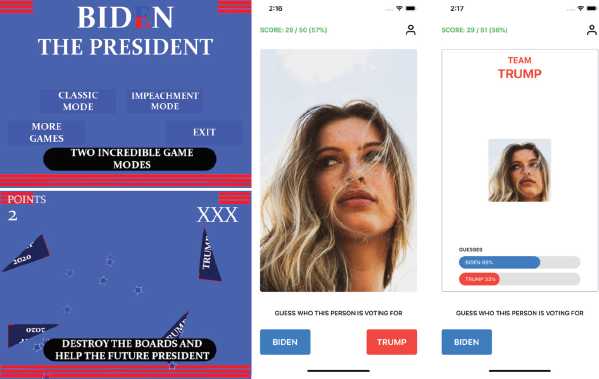

Lastly, a family of apps (10.89%) was detected that placed the focus on other issues and used the candidates’ names as clickbait. This group matched the 16 apps identified in the section on the tone of discourse framed as being “escapist”, such as Biden: The President (RZL Studios Games, 2020), a rather meaningless game that used Biden’s name in its development, and Joe Biden vs Donald Trump 2020 (Hergott Technologies, Inc. 2020), where pictures of anonymous people appeared in the format of the dating app Tinder, and the user had to guess whether they were a Trump or Biden supporter and swipe left or right.

Discourse modes

The classification by mode of discourse revealed that almost half of the apps (49) simplified their message. For example, some of them offered a countdown, such as Election Widget - Vote 2020! (Henadz Mikhailau, 2020) which incorporated a widget into the device with the time remaining until election day.

In contrast to these, others attempted to form a more complex and elaborate discourse (38). Among them there were apps such as the official campaign apps of both candidates or campaign simulators, as well as games with didactic purposes such as Presidential Elections Game (Multieducator Inc, 2015), or the aforementioned The Election (JC Nichols LLC, 2020).

Reproduced discourse was seen in models such as Realpoll: US Election Polls (Two Dreams LLC, 2019), which gathered the latest developments in the election polls along with news or information on the representatives that people could vote for in their geographical area; and US Election Hub 2020 (Simon Houghton, 2020), which compiled results information from various polls and media outlets and created graphs with candidates’ historical background or averages. However, there were apps such as TRUMP 2020 - Tweets News Live (Google Tech Eli Bitton, 2020) which simply reproduced President Trump’s tweets, and 2020 Election (Mobile App Media 101, 2020), which reused the information it collected from the Federal Election Commission website.

Discussion and conclusions

The 2020 US election were among the most turbulent in recent decades, as they took place against the backdrop of an exceptional scenario in recent history. The global pandemic sowed uncertainty in areas such as the voting system, debate mechanisms, the incidence of infections and deaths from covid-19, and led to the rise of denialists and fake news. The first research question in this study aimed to show the impact that the US presidential election had on the mobile ecosystem. It was seen that Biden’s and Trump’s campaign messages were not as striking for the mobile ecosystem as they were for Trump’s nomination in 2016, which generated a very productive dynamic with more than 400 apps.

However, there was a tendency to insert one of the candidates’ names in apps to use them for advertising purposes, even if they were not the main character of the app. A strategy that resorted to clickbait to try to make apps profitable. This was already evident in the 2016 election when other developers used Trump’s name for promotional purposes in an attempt to appear in search results for a trending keyword (McCabe & Nelson, 2016).

The second research question sought to identify what kind of message was put forward in the most downloaded apps, and what the main features of their discourse were. The narrative in the Trump-themed apps seemed, at first, less complex than those related to Biden, but the sum of futile apps (such as poorly thought-out games or those containing downloadable emoticons) obtained similar numbers for both candidates: Trump, 23, and Biden, 25. Therefore, both candidates seemed to attract the same level of narrative complexity. With regard to the content of the apps themselves, it should not go unnoticed that, based on the assumption that simulators could be an entertaining way to learn how electoral voting and possible scenarios work, they would fit into the theme of games, accounting for 51% of the total number of apps, which means that attention was once again focused on the politainment approach. The main focus of attention in apps were campaign development (31%) and candidates (39%), which means that the majority of apps were centered on actual electoral activities and led to a rise of personalized politics. In this sense, the apps became an extension of the campaign through other means.

In addition, it was found that entertainment-based applications (47) were in the majority, whereas apps aimed at providing information on voting day procedures, how voting centers worked, or offering election data barely reached 19%. Thus, it can be seen that the apps were impervious to the events of the electoral campaign itself, as they had no direct relationship with them, but rather were intended to go viral to the detriment of political current affairs. This can also be seen in the tone of the discourse they employed, as a high percentage of apps (39%) were used to mock candidates or simply to publicize developers’ creations even though they were not linked to the election. The discourse evolved as the election campaign progressed and the tone varied throughout this period, which makes it impossible to identify a specific pattern. However, there is evidence that apps were influenced by the electoral period, as two thirds of the total sample were created on the occasion of the presidential election.

Nevertheless, this exploratory study has found that apps accentuated the trend of rapid mobile content creation without being influenced by political discourse or campaign development. Likewise, the hegemony of the apps that prioritized the most viral aspects of political discourse was confirmed over those that were less focused on political-electoral current affairs. In this way, more common themes on the media’s news agenda such as the pandemic, denialist tendencies, anti-vaccination groups, bleach ingestion or conspiracy theories of any kind were not found.

Therefore, according to the data, there was no strong political engagement that connected the apps and the 2020 political and election context. No close relationship was identified between the relevant campaign events covered by the media and the emergence of apps, nor were clear patterns found, beyond a proliferation of new apps that were created by leveraging on the mischievousness of developers and the curiosity of users.

REFERENCES

Abuín-Vences, N. & García-Rosales, D. (2020). Elecciones generales de 2019 en Twitter: eficacia de las estrategias comunicativas y debates televisados como motor del discurso social. Profesional de la Información, 29(2), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.mar.13 [ Links ]

Baltar, F. & Brunet, I. (2012). Social research 2.0: virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Internet Research, 22(1), 57-74. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662241211199960 [ Links ]

Ballesteros-Herencia, C. A. & Gómez-García, S. (2020). Batalla de frames en la campaña electoral de abril de 2019. Engagement y promoción de mensajes de los partidos políticos en Facebook. Profesional de la Información, 29(6), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.nov.29 [ Links ]

Bartsch, A. & Schneider, F. M. (2014). Entertainment and Politics Revisited: How Non-Escapist Forms of Entertainment Can Stimulate Political Interest and Information Seeking. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 369-396. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12095 [ Links ]

Berrocal, S. & Cebrián, E. (2009). El infoentretenimiento político televisivo. Un análisis de las primeras intervenciones de Zapatero y Rajoy en Tengo una pregunta para usted. Textual & Visual Media: Revista de la Sociedad Española de Periodística, 2, 41-60. https://bit.ly/2PR0Z9r [ Links ]

Berrocal, S., Martín-Jiménez, V. & Gil-Torres, A. (2017). Líderes políticos en YouTube: Información y politainment en las elecciones generales de 2016 (26J) en España. Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 937-946. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.15 ISSN 1699-2407 [ Links ]

Berrocal, S., Redondo, M. & Campos, E. (2013). Una aproximación al estudio del infoentretenimiento en Internet: Origen, desarrollo y perspectivas futuras. AdComunica, (4), 63-79. http://doi.org/10.6035/2174-0992.2012.4.5 [ Links ]

Boukes, M. (2019). Infotainment. En T. P. Vos, F. Hanusch, D. Dimitrakopoulou, M. Geertsema-Sligh & A. Sehl (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies; Forms of Journalism (pp. 1-9). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118841570.iejs0132 [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2009). Comunicación y poder. Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Cervi, L., Tejedor, S. & Lladó, C. M. (2021). TikTok and the new language of political communication. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, 26, 267-287. https://doi.org/10.6035/clr.5817 [ Links ]

Claes, F. & Deltell, L. (2015). Audiencia social en Twitter: hacia un nuevo modelo de consumo televisivo. Trípodos, 36, 111-132. https://bit.ly/3eyWLgK [ Links ]

Gentzkow, M. (2006). Television and Voter Turnout. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(3), 931-972. https://doi.org/10.1162/ qjec.121.3.931 [ Links ]

Glas, R., Lammes, S., de Lange, M., Raessens, J. & de Vries, I. (2019). The playful citizen: An introduction. En R. Glas, S. Lammes, M. de Lange, J. Raessens & I. de Vries (Eds.), The Playful Citizen: civic engagement in a mediatized culture (pp. 9-30). Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.5117/9789462984523 [ Links ]

Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine Press. [ Links ]

Gil-Ramírez, M., de Travesedo-Rojas, R. G. & Almansa-Martínez, A. (2019). Politainment and political personalisation. From television to YouTube? Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (74), 1542-1564. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2018-1398en [ Links ]

Gil-Torres, A., Martín-Quevedo, J., Gómez-García, S. & San José-De la Rosa, C. (2020). El coronavirus en el ecosistema de los dispositivos móviles: creadores, discursos y recepción. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (78), 329-358. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1480 [ Links ]

Gómez-García, S., Gil-Torres, A., Carrillo-Vera, J. A. & Navarro-Sierra, N. (2019). Creando a Donald Trump: Las apps en el discurso político sobre el presidente de Estados Unidos. Comunicar, 59, 49-59. https://doi.org/10.3916/C59-2019-05 [ Links ]

Gómez-García, S., Paz-Rebollo, M. & Cabeza-San-Deogracias, J. (2021). Newsgames against hate speech in the refugee crisis. Comunicar, 67, 123-133. https://doi.org/10.3916/C67-2021-10 [ Links ]

González-Neira, A. & Quintas-Froufe, N. (2014). Audiencia tradicional frente a audiencia social: un análisis comparativo en el prime-time televisivo. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 5(1), 105-121. https://bit.ly/38uyWTw [ Links ]

Haigh, M. & Heresco, A. (2010). Late-night Iraq: Monologue joke content and tone from 2003 to 2007. Mass Communication & Society, 13(2), 157-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205430903014884 [ Links ]

Holbert, R. L., Hill, M. R. & Lee, J. (2014). The political relevance of entertainment media. En C. Reinemann (Ed.), Political Communication (pp. 427-446). De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110238174.427 [ Links ]

Johnson, T. J., Saldaña, M. & Kaye, B. K. (2021). A galaxy of apps: Mobile app reliance and the indirect influence on political participation through political discussion and trust. Mobile Media & Communication, 10(1), 21-37. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579211012430 [ Links ]

Kleina, N. C. M. (2020). De herói de jogos a adesivo no WhatsApp: da imagem de Jair Bolsonaro retratada em aplicativos para celular. Revista Mediação, 22(30), 42-51. http://revista.fumec.br/index.php/mediacao/article/view/7770 [ Links ]

Krippendorf, K. (2004). Reliability in Content Analysis. Some Common Misconceptions and Recommendations. Human Communication Research, 30, 411-433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00738.x [ Links ]

Krippendorf, K. (2013). Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Sage [ Links ]

Light, B., Burgess, J. & Duguay, S. (2016). The walkthrough method: An approach to the study of apps. New Media & Society, 20(3), 881-900. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816675438 [ Links ]

McCabe, W. & Nelson, R. (2016, 23 de marzo). App store data offers unique insights into the 2016 Presidential Race [Entrada de blog]. Sensor Tower. https://bit.ly/2ccpGW3 [ Links ]

Navarro-Sierra, N. & Quevedo-Redondo, R. (2020). El liderazgo político de la Unión Europea a través del ecosistema de aplicaciones móviles. Revista Prisma Social, (30), 1-21. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/3731 [ Links ]

Neys, J. & Jansz, J. (2010). Political Internet games: Engaging an audience. European Journal of Communication, 25(3), 227-241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323110373456 [ Links ]

Nielsen. (2020, 30 de septiembre). Media Advisory: First Presidential Debate of 2020 Draws 73.1 Million Viewers. https://bit.ly/2ZnrZ58 [ Links ]

Pacheco Barrio, M. A. (2022). El espectáculo de la política en ‘El Hormiguero 3.0’con los candidatos a la presidencia del Gobierno: 2015-2019. index.comunicación, 12(1), 121-150. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/12/01Elespe [ Links ]

Puebla, B. & Farfán, J. (2018). Gestión de la comunicación interna a través de las aplicaciones para móviles. Caso de estudio: El Corte inglés. Prisma Social, 22, http://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/2590/2755 [ Links ]

Quevedo-Redondo, R., Navarro-Sierra, N., Berrocal-Gonzalo, S. & Gómez-García, S. (2021). Political Leaders in the APP Ecosystem. Social Sciences. Social Science, 10(8), 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080307 [ Links ]

Riegert, K. & Collins, S. (2016). Politainment. En G. Mazzoleni (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication (pp. 1-10). Wiley. https://doi.org/doi:10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc157 [ Links ]

Riffe, D., Lacy, S. & Fico, F. (2019). Analyzing media messages. Using quantitative content analysis in research. Routledge. [ Links ]

Segado-Boj, F., Gómez-García, S. & Díaz-Campo, J. (2022). The intellectual and thematic structure of Communication research in Scopus (1980-2020): a comparative perspective among Spain, Europe, and Latin America. Profesional de la Información, 31(1), e310110. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.ene.10 [ Links ]

Serazio, M. (2018). Producing Popular Politics: The Infotainment Strategies of American Campaign Consultants. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 62(1), 131-146. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2017.1402901 [ Links ]

Statcounter. (2021). Mobile Operating System Market Share United States of America. https://bit.ly/3EgsPj6 [ Links ]

Vázquez-Sande, P. (2016). Políticapp: hacia una categorización de las apps móviles de comunicación política. Fonseca Journal of Communication, 12(1), 59-78. http://doi.org/10.14201/fjc2016125978 [ Links ]

Zamora-Medina, R., Losada-Díaz, J. C. & Vázquez-Sande, P. (2020). A taxonomy design for mobile applications in the Spanish political communication context. Profesional de la Información, 29(3). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.27 [ Links ]

Zamora Medina, R., Gómez García, S. & Martínez Martínez, H. (2021). Los memes políticos como recurso persuasivo online. Análisis de su repercusión durante los debates electorales de 2019 en España. Opinião Publica, 27(2), 681-704. http://doi.org/10.1590/1807-01912021272681 [ Links ]

Zamora-Martínez, P. & González Neira, A. (2022). Estudio de la audiencia social en Twitter de los formatos de ‘politainment’ en España. El caso de ‘El Intermedio’. index.Comunicación, 12(1), 21-45. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/12/01Estudi [ Links ]

1This study is the result of an R&D&I Research Project entitled “Politainment in the face of media fragmentation: disintermediation, engagement and polarization” (PID2020-114193RB-I00) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation; and “IBERIFIER. Iberian Media Research & Fact-Checking” (2020-EU-IA-0252) funded by the European Commission.

How to cite:

Gil-Torres, A., Navarro-Sierra, N., San José-de la Rosa, C. & Herranz-Rubio, C. (2022). The app ecosystem in the 2020 US election: information or politainment. Comunicación y Sociedad, e8191. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.8191

Received: June 28, 2021; Accepted: October 08, 2021; Published: May 04, 2022

texto en

texto en