INTRODUCTION

The first study of amphibians and reptiles from the Pleistocene in Mexico was performed by Langebartel (1953) in many sites of the Yucatán peninsula. Langebartel (1953) reported six taxa of anurans, lizards and snakes and described two extinct species, an iguanid (Ctenosaura premaxillaris) and a xantusiid (Lepidophyma arizeloglyphus). Both species are still valid (Reynoso, 2006; Chávez-Galván et al., 2013). Other herpetofaunal studies of the Pleistocene in southern Mexico include the description of Trachemys in Tabasco, Trachemys scripta, Kinosternon scorpioides and Staurotypus sp. in Chiapas (Luna-Espinoza and Carbot-Chanona, 2009), Kinosternon hirtipes/integrum and Gopherus sp. in Oaxaca (Cruz et al., 2009) and Claudius angustatus and Crocodylus sp. in Veracruz (Peña-Serrano et al., 2004).

One of the most intensively studied sites in the Yucatán peninsula is Loltún cave. The only sites in Mexico that have been systematically excavated with controlled stratigraphy are Loltún cave and San Josecito cave, Nuevo León (Arroyo-Cabrales and Polaco, 2003). Since the last years of the 1980 decade, the archaeological and paleontological significance of Loltún cave was emphasized by the discovery of Pleistocene fauna and lithic tools (Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003). It is one of the few sites in southern Mexico that has Pleistocene fossil amphibians and reptiles. The paleontological studies of Loltún cave have focused on mammals (Hatt, 1953; Álvarez and Polaco, 1972; Mercer, 1975; Cope, 1896; Álvarez and Arroyo-Cabrales, 1990; Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 1990, 2003), pollen (Xelhuantzi-López, 1986; Montúfar, 1987), mollusks (Álvarez and Polaco, 1972), birds (Fisher, 1953) and amphibians and reptiles (Langebartel, 1953).

Amphibians and reptiles can be good paleoecological proxies because they are ecologically, ethologically and physiologically restricted to microhabitats and specific environments, and many species have restricted geographic intervals and are territorial (Vitt and Caldwell, 2014). These animals are specialized to certain climatic conditions allowing the reconstruction of environments from past climates (Holman, 1995; Blain et al., 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016). In this study, fossil amphibian and reptile remains from Loltún cave were analyzed in order to infer 1) the site paleoenvironment and paleoclimate and 2) the changes in the amphibian and reptile communities during the Late Pleistocene in the Yucatán peninsula.

Loltún cave

Loltún cave is located in the southwest portion of the state of Yucatán (México), about 110 km south of Mérida and 7 km southwest from Oxcutzcab, at an elevation of 40 m a.s.l. Its geographic coordinates are 20°15’14.35”N and 89°27’20.82”W (Figure 1). The site is located on the foothills of the sierra de Ticul, in a karst region with several types of solution features exposed in Miocene rocks (Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003). Loltún cave is an east-west-oriented series of tunnels and chambers. It has nine chambers of which Loltún and Nahkab are used as the beginning of a tourist route. The excavations from which the fossil material for this study was obtained were made in the Huechil chamber (Huech means armadillo in maya language) (Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 1990).

Figure 1 Loltún cave in Yucatán (black point). Habitat types found in the Yucatán peninsula and north Central America: tropical rainforest (TRF), evergreen seasonal forest (ESF), tropical semi-deciduous forest (TSDF), tropical deciduous forest (TDF), scrub forest (SF) and montane systems (MS). Modified map from Correa-Metrio et al. (2011).

The excavations were carried out using a metric grid and controlled stratigraphy during four seasons between 1977 and 1981. The levels or layers of the sequence can be divided into three main groups (Figure 2) (Schmidt, 1988; Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003):

Figure 2 Stratigraphy (redrawn from Álvarez and Polaco, 1972) of El Toro Unit, Loltún cave, Yucatán peninsula. H 11-14, excavation boxes. Layer I, dark brown sediment; Layer II, light brown sediment; Layer III, dark brown sediment; Layer IV, dark brown sediment with rocks; Layer V, bed rocks; Layer VI, dark red sediment; Layer VII, red sediment; Layer VIII, light red sediment; Layer IX, dark red sediment; Layer X, light red sediment; Layer XI, volcanic ash (Rosseau tephra); Layer XII, red sediment; Layer XIII, compacted dark red sediment; Layer XIV, dark red sediment; Layer XV, compacted dark red sediment; Layer XVI, yellow red clay.

Group 1. Levels I to VII are from the Ceramic Stage, but extinct animal remains are found in the bottom of level VII.

Group 2. Level VIII is from the Pre-Ceramic Stage; it includes some lithic elements and extinct fauna.

Group 3. Levels IX to XVI are Pleistocene in age, without any cultural material. Volcanic ash correlated to the Rosseau tephra was dated as 28,400 yrs BP by radiocarbon method (uncalibrated, Rampino et al., 1979) and 32782 ± 296 cal yrs BP (Danzeglocke, 2007), and occurs in level XI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fossil remains

The amphibian and reptile fossils studied were found in Loltún cave in the sequences reported as Group 3 which comprises levels XII to XVI, which are older than 32782 ± 296 cal yrs BP (Rampino et al., 1979; Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003). The fossil remains were compared to reference osteological material from the Laboratorio de Arqueozoología “M. en C. Ticúl Álvarez Solórzano”, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (DP) and the Colección Nacional de Anfibios y Reptiles, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (CNAR). The bones were identified using the criteria given by Holman (2003) for anurans, Auffenberg (1963), LaDuke (1991) and Holman (2000) for snake vertebrae and their regionalization, Evans (2008) for lizards and Preston (1979) for turtles. The remains were labeled as LC (Loltún cave), number of excavation and the level in roman numbers from which the material was obtained.

Paleoenvironmental reconstruction

In order to reconstruct the paleoenvironment, we used the Habitat Weighting Method with six different types of habitats found in the Yucatán peninsula and northern Central America: tropical rainforest (TRF), evergreen seasonal forest (ESF), tropical semi-deciduous forest (TSDF), tropical deciduous forest (TDF), scrub forest (SF) and montane systems (MS), described by Correa-Metrio et al. (2011) (Figure 1). This method consists in establishing, first, the present-day habitat distribution of each amphibian and reptile taxon. Each species receives a score for each habitat type proportional to habitat preference; the sum of scores for all habitat types for each species is 1 (Blain et al., 2008). The reconstruction of the paleoenvironment at the study site during the Late Pleistocene was determined by summing the scores of each habitat type for all species. The habitat type with the highest score is interpreted as the predominant habitat type.

Paleoclimatic reconstruction

The Mutual Climatic Range (MCR) method was used to reconstruct the Late Pleistocene paleoclimate around Loltún cave. This method consists in calculating the potential paleoclimatic conditions by identifying the geographic region where all the species in the locality or in a stratigraphical level currently live (Blain et al., 2009). It is assumed that the overlapping areas of the current distribution of each taxon occurring in the locality contain the climatic conditions that were present in the past; in other words, the climatic conditions that were present in the locality where the fossil community was found, are represented by the overlapping of the current distributions.

For each fossil taxon a species distribution model (SDM) was constructed. To accomplish this, locality data from natural history collections such as Sistema Nacional de Información sobre la Biodiversisdad (CONABIO, www.conabio.org.mx), the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, www.gbif.org), data reported in literature (Lee, 1996, 2000; Campbell, 1999; Köhler, 2003, 2010) and the Colección Nacional de Anfibios y Reptiles (CNAR), Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, were used.

The SDMs were constructed using the MaxEnt v3.3 software (Phillips et al., 2006), which allows the use of SDMs for exploring and predicting the taxon’s distribution even when using a small sample size (Wisz et al., 2008). For each species, ten distinct models were generated using the bootstrap sampling and each model was validated with 30% of the original records. To evaluate the model, the area under the curve (AUC) generated with the ROC technique (Receiver Operating Characteristic) was used. The potential distribution was obtained by reclassifying with the 10 percentile training presence from the average of the ten models made for each species. As a result, a binary map was created showing the optimal climatic conditions (1 = optimal, 0 = not optimal) for each of the living taxa that represent the fossil amphibian and reptiles found in Loltún cave, Yucatán.

The values of mean annual temperature (MAT) and mean annual precipitation (MAP) for the Late Pleistocene in Loltún cave obtained with the mutual climatic range method were compared with Oxkutzab, Yucatán, the closest weather station to the Loltún cave (smn.cna.gob.mx).

RESULTS

From the fossil remains found in the Loltún cave, we were able to identify one amphibian (Rhinella marina), and two lizards (Ctenosaura defensor and C. similis). We also found fossils from one lizard that belongs to Ctenosaura subgenus Loganiosaura; five snakes from the genera Boa, Coluber, Drymarchon, Lampropeltis and Leptophis, and a turtle from genus Trachemys.

Systematic paleontology

Class Amphibia Blainville, 1816

Order Anura Fischer von Waldheim, 1813

Family Bufonidae Gray, 1825

Genus RhinellaFitzinger, 1826

Rhinella marina Linnaeus, 1758

Figure 3 Rhinella marina fossil remains found in Loltún cave. Seventh trunk vertebra in posterior view (a), dorsal view (b) and lateral view (c). Left radio-ulna (d). Left astragalus (e). Scale bar = 5 mm.

Rana marinaLinnaeus, 1758, Systema Naturae, Ed. 10, 1:211.

Bufo marinusSchneider, 1799, Historia Amphibiorum Naturalis: 219.

Chaunus marinusFrost et al., 2006, Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 297:364.

Rhinella marinaPramuk et al., 2008, Herpetologica, 63:211.

Description. The radio-ulna (LC 360-XII) is slightly constricted. It has a large quadrangular radio-ulnar foramen. Its Y element’s process is in form of a spine. The separation between the radial process and the ulnar process is weak. The radial process is conserved up to the middle of the ulnar part. In dorsal view, the trochanter diverges at an angle of 90°. It has an ulnar keel. In lateral view, the anterior radio-ulna edge is slightly angled.

The seventh vertebra (LC 360-XII) has an oval cotyle with dorsal edges in a U-like form. The neural spine is thin and short. The separation between the prezygapophyseal articular facets is less than their width. The postzygapophyseal keel merges from the posterior neural spine. The neural arch is depressed and concave.

The astragalus (LC 359-XII) has a distal canal, a smooth torsion of the element, and a robust form. The distal epiphyses has a triangular cross-section.

Material. Left radio-ulna (LC 360-XII), a seventh vertebra (LC 360-XII) and a left astragalus (LC 359-XII).

Discussion. The size of the material can only be compared to big anurans of the country like Rhinella marina (DP 732), Lithobates catesbeianus (DP 5086) and Lithobates megapoda (CNAR 15686). The radio-ulna is referred to Rhinella marina because they share the following characteristics: a smooth constriction, a quadrangular radio-ulnar foramen, spine-like Y process, a short distance between the radial and ulnar process, a trochanter deviation of 90°, and a slightly angled anterior edge (Table 1). The seventh vertebra is referred to R. marina because of the presence of an oval cotyle with dorsal edges in U-like form and a thin and short neural spine. The separation between the prezygapophyseal articular facets is short and a postzygapophyseal keel merges from the posterior neural spine (Table 2). The material described above is morphologically congruent with the osteological characters of Rhinella marina.

Table 2 Comparison of the seventh vertebra between Rhinella, Lithobates and fossil material (LC 360-XII).

Class Reptilia Laurenti, 1768

Order Squamata Oppel, 1811

Family Iguanidae Oppel, 1811

Genus CtenosauraWiegmann, 1828

Ctenosaura defensor Cope, 1866

Figure 4 Fossil iguanid remains found in Loltún cave. Ctenosaura defensor left dentary (a). Ctenosaura subgenus Loganiosaura right maxilla (b). Ctenosaura similis sacral vertebra in posterior (c) and anterior view (d). Scale bar = 5 mm.

Cachryx defensorCope, 1866, Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 18:124.

Ctenosaura defensorGünther, 1890, Biologica Centrali-Americana, Reptilia and Batrachia: 58.

Enyaliosaurus defensor Smith and Taylor, 1950, Bulletin of the United States National Museum, 199:77.

Ctenosaura (Enyaliosaurus) defensor Köhler et al., 2000, Amphibia-Reptilia, 21:188.

Description. The left dentary (LC 374-XIII) is small (19.8 mm). It has a closed Meckelian canal without sutures. This element shows 18 tooth positions, 14 of which preserve complete teeth. The teeth are pentacuspid.

Material. A left dentary (LC 374-XIII).

Discussion. The material here described can be confidently referred to Ctenosaura defensor on the basis of the characters discussed by de Queiroz (1987). A relevant character is the closed Meckelian canal without sutures present in all iguanids (Figure 4a). The identification is straightforward excluding the genus Dipsosaurus and some species of Ctenosaura (C. acanthura, C. clarki, C. hemilopha, C. palearis, C. pectinata and C. similis) because the teeth in these taxa have a maximum of four cusps. The presence of pentacuspid teeth is characteristic of Ctenosaura defensor and Cyclura pinguis excluding other polycuspid genus Cyclura, Sauromalus and Iguana) with six or more cusps. However, C. pinguis is excluded because it has a bigger dentary than C. defensor. The size of the latter is more consistent with the fossil remains.

Ctenosaura similis Gray, 1831

Iguana (Ctenosaura) similisGray, 1831 in Griffith and Pidgeon (eds.), The animal kingdom arranged in conformity with its organization by the Baron Cuvier with additional descriptions of all species higher named, and of many before noticed, 38 p.

Ctenosaura similisBailey, 1929, Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 73:32.

Ctenosaura (Ctenosaura) similis Köhler et al., 2000, Amphibia-Reptilia, 21:187.

Material. A posterior fragment of the left maxilla (LC 367-XII-XIII), first and second sacral vertebrae (LC 367-XII-XIII, LC 360-XII), two cervical vertebrae (LC 361-XII), six trunk vertebrae (LC 357-XIII, 359-XII, 361-XII, 367-XII-XIII) and six caudal vertebrae (LC 357-XIII, 359-XII, 361-XII, 362- XII, 367-XII-XIII).

Discussion. The fossils were compared with recent osteological material of Ctenosaura similis and C. pectinata, without finding important differences in the maxilla or the trunk vertebrae. The fossil material is referred to C. smilis because they share the following characteristics: the sacral vertebra have a neural spine that overhangs dorsally, in the first sacral vertebra, the distal part of the pleurapophysis is large and flat and the condyle of the second sacral vertebra is dorsoventrally large. These characteristics differ from C. pectinata.

Genus Ctenosaura Wiegmann, 1828

Subgenus Loganiosaura Köhler et al., 2000

Ctenosaura Stejneger, 1901, Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 23:467.

Enyaliosaurus Cochran, 1961, United States Natural Museum Bulletin, 1961:105.

Ctenosaura subgenus LoganiosauraKöhler et al., 2000, Amphibia-Reptilia, 21:187.

Type species. Ctenosaura bakeriStejneger, 1901.

Description. A right maxilla. This element shows 16 tooth positions, eight of which preserved complete teeth. The teeth are tetracuspid. The anterior part of the maxilla has a ventral straight edge.

Material. Right maxilla (LC 359-XII).

Discussion. The genus Ctenosaura includes three subgenera: Enyaliosarus, Ctenosaura and Loganiosaura (de Queiroz, 1987). The subgenus Enyaliosarus is composed of Ctenosaura quinquecarinata complex (Hasbún et al., 2005) which can be excluded because the species of this group have tricuspid teeth (e.g. C. oaxacana) or pentacuspid (e.g. C. defensor). Tetracuspid teeth are found in the subgenera Ctenosaura and Loganiosaura, of which the subgenus Ctenosaura is excluded because the anterior part of the fossil maxilla is straight (Oelrich, 1956; de Queiroz, 1987). The subgenus Loganiosaura is composed of four species, of which de Queiroz (1987) mentions that C. bakeri has tricuspid teeth and C. palearis tetracuspid teeth. There is no reference osteological material for the other two species, C. melanosterna and C. oedirhina, so the fossil remains were only identified at the subgenus level.

Family Boidae Gray, 1825

Genus BoaLinnaeus, 1758

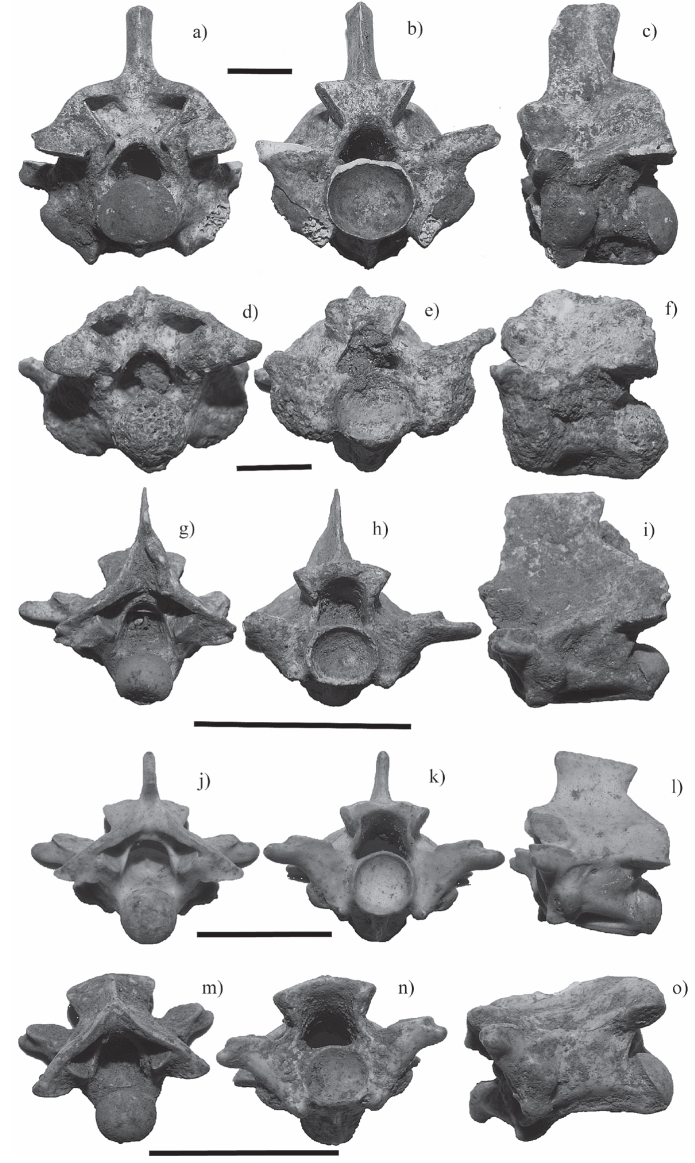

Figure 5 Fossil trunk vertebrae of the snakes found in Loltún cave. Boa constrictor (a,b,c), Drymarchon melanurus (d,e,f), Coluber (g,h,i), Lampropeltis (j, k, l), and Leptophis (m, n, o). Posterior view (a, d, g, j, m), anterior view (b, e, h, k, n) and lateral view (c, f, i, l, o). Scale bar = 5 mm.

BoaLinnaeus, 1758, Systema Naturae, Ed. 10, 1:215.

ConstrictorMartin, 1958, Miscellaneous publications, Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, 101:67.

Type species. Boa constrictor Linnaeus, 1758.

Material. Three cervical vertebrae (LC 363-XII, 372-XIII, 378-XVI), six anterior trunk vertebrae (LC 357-XIII, 370-XIII, 371-XIII) and four posterior trunk vertebrae (LC 360 XII, 362-XII, 370-XIII).

Discussion. The material can be referred to Boa on the basis of the character discussed, among others, by Holman (1981, 2000), Albino and Carlini (2008) and Albino (2011). The fossil vertebrae present diagnostic characters such as: robust, tall and short form; a tall neural arch and spine; small prezygapophyseal processes; diapophysis and parapophysis are slightly distinguished; cotyles and condyles are bigger than the neural canal; a robust zygosphene and the neural arch is clearly convex. Hynková et al. (2009) and Card et al. (2016) separated Boa constrictor into three species B. constrictor, B. imperator and B. sigma. There are no osteological studies available to separate the fossil material to a specific level, so the fossil remains were only identified at the genus level.

Family Colubridae Oppel, 1811

Genus DrymarchonFitzinger, 1843

DrymarchonBoie, 1827, Bermerkungen über Merrem´s Versuch eines Systems der Amphibien, 1. Lieferung, Ophidier: Isis van Oken, 20, 508-566.

Coluber Boie, 1827, Bermerkungen über Merrem´s Versuch eines Systems der Amphibien, 1. Lieferung, Ophidier: Isis van Oken, 20, 508-566.

Spilotes melanurusDuméril, Bibron and Duméril, 1854, Erpétologie Genérale ou Histoire Naturelle Complète des Reptiles, 9, 224.

DrymarchonStuart, 1935, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Miscellaneous Publications 29: 49.

Type species. Drymarchon corais Boie, 1827.

Material. Seven anterior trunk vertebrae (LC 356-XII, 359-XII, 361-XII, 364-XII, 374-XIII) and two posterior trunk vertebrae (LC 360-XII, 361-XII).

Discussion. The material can be referred to Drymarchon on the basis of the characters discussed by Auffenberg (1963) and Holman (2000). The fossil vertebrae present relevant characters such as, evident subcentral bridges, in ventral view the centrum is subtriangular; a gladiate hemal keel; epizygapophyseal spines and in posterior and dorsal view the accessory processes overhang laterally. Molecular studies (Wüster et al., 2001) separated D. corais into three species D. corais, D. melanurus and D. caudomaculatus so that new osteological studies should be performed to identify our fossil remains to a specific level.

Genus Coluber (Masticophis) Baird and Girard 1853

LeptophisHallowell, 1852, Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 6:181.

MasticophisBaird and Girard, 1853, Catalogue of North American Reptiles in the Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, 103.

ColuberUtiger et al., 2005, Russian Journal of Herpetology, 12:51.

Type species. Coluber constrictor Linnaeus, 1758.

Material. An anterior trunk vertebra (LC 362-XII).

Discussion. Meylan (1982), LaDuke (1991) and Holman (2000) mention that the differences between the vertebrae from Masticophis and Coluber are not clear. Molecular studies have supported the synonymy of the genus Masticophis with Coluber (Utiger et al., 2005), giving a possible explanation for the osteological similarity of the vertebrae between these genera. Despite this, Auffenberg (1963), Meylan (1982) and LaDuke (1991) identify the genus Masticophis on the basis of the following characteristics: long vertebrae with convex neural arch; a subquadrangular neural canal with a dorsal edge smaller than the ventral one; round postzygapophyseal articular facets; long, thick and blunt accessory processes; slightly developed subcentral ridges; gladiate hemal keel and epizygapophyseal spines. The fossil remain presents all of the characteristics mentioned above allowing us identify it as the genus Masticophis.

Genus Lampropeltis Linnaeus, 1766

ColuberLinnaeus, 1766, Systema Naturae per regna tria nature, secundum clases, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus differentiis, synonymis, locis: 328.

HerpetodryasSchlegel, 1843, Essay on the physiognomy of serpents: 152.

OphibolusBaird and Girard, 1853, Catalogue of North American Reptiles in the Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, 85.

CoronellaDuméril, Bibron and Duméril, 1854, Erpétologie Genérale ou Histoire Naturelle Complète des Reptiles, 9:616.

TriaeniopholisWerner, 1924, Gedruckt mit Unterstützung aus dem Jerome und Margaret Stonborough-Fonds, 133:50.

LampropeltisPyron and Burbrink, 2009, Zootaxa, 2241:24.

Type species. Lampropeltis getula Linnaeus, 1766.

Material. A cervical vertebra (LC 366-XII), four anterior trunk vertebrae (LC 359-XII, 366-XII, 372-XIII) and a posterior trunk vertebra (LC 356-XII).

Discussion. Genus Lampropeltis is diagnosed by the following characteristics: vertebrae are wider than long; a strongly depressed neural arch; cotyle is bigger than the neural canal; moderately blunt accessory processes; slightly developed subcentral ridges; thin and gladiate hemal keel and it does not have epizygapophyseal spines (Auffenberg, 1963, Meylan, 1982; Holman, 2000). The fossil remains present all of the characteristics mentioned above allowing us identify them as genus Lampropeltis.

Genus Leptophis sp. Linnaeus, 1758

Coluber Linnaeus, 1758, Systema Naturae, Ed. 10, 1:225.

LeptophisBell, 1825, Zoological Journal, London, 2:328.

AhaetullaGray, 1831, in Griffith and Pidgeon, The animal kingdom arranged in conformity with its organisation by the Baron Cuvier with additional descriptions of all the species higher named, and of many before noticed, 93.

DendrophisSchlegel, 1837, Essai sur la physionomie des serpens, 224.

Type species. Leptophis ahaetulla Linnaeus, 1758.

Description. Long, narrow and flattened vertebrae. In anterior view, the cotyles are laterally subrounded, slightly bigger than the neural canal; a convex zygosphene; short accessory processes that overhang laterally. In posterior view, the neural arch is convex and slightly flattened; it has a keel between the parazygantral facet and the postzygapophyseal articular facet; circular condyle. In dorsal view, the zygosphene is convex; rounded, subtriangular or oval prezygapophyseal articular facets; short, wide and rounded accessory processes; the neural spine is no longer than the posterior part of the neural arch. In ventral view, the anterior trunk vertebrae have a short gladiate hemal keel which is only evident in the posterior part of the centrum; the posterior trunk vertebra does not have a hemal keel. It has a long subtriangular to cylindrical centrum; the articular postzygapophyseal facets are rounded or subtriangular; weak or absent subcentral ridges. In lateral view, interzygapophyseal ridges are absent; the neural spine is long and short and the anterior edge beveled; and centrum deeply concave.

Material. Two anterior trunk vertebrae (LC 57-XIII, 359-XIII) and a posterior trunk vertebra (LC 359-XII).

Discussion. Leptophis Pleistocene fossil remains are here described for the first time for México (Chávez-Galván et al., 2013). Osteological studies of Leptophis have focused on the skull (Oliver, 1948; Wilson, 1970; Souza and Lema, 1990) making this study the first one to describe Leptophis vertebrae. The vertebrae are characterized by a concave centrum and a hemal keel in the posterior part. We could only identify the fossil remains as Leptophis because only L. mexicanus had reference osteological material.

Order Testudines Batsch, 1788

Family Emydidae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus TrachemysAgassiz, 1857

Figure 6 Trachemys fossil remain found in Loltún cave. Ninth peripheral bone (a), cervical vertebra (b) and caudal vertebra (c). Scale bar = 5 mm.

TrachemysAgassiz, 1857, Contributions to the Natural History of the United States of America, North American Testudinata, 252.

CallichelysGray, 1863, Annals and Magazine of Natural History 13:181

RedamiaGray, 1870, Supplement to the Catalogue of Shield Reptiles in the Collection of the British Museum. Testudinata, 35.

Type species. Trachemys terrapen Bonnaterre, 1789.

Description. Fragment of the ninth right peripheral bone. In exterior view, imprints of the ninth and tenth marginals scutes are present. The fifth costal can be seen in the upper part. In the visceral surface, the characteristic bulge of the last scutes with a small central foramen can be seen.

Material. Ninth right peripheral bone (LC 356-XII), two cervical vertebrae (LC 360-XII, 363-XII) and a caudal vertebra (LC 362-XII).

Discussion. The ninth right peripheral was compared with reference osteological material of Rhinoclemmys and Trachemys assigning the fossil material to Trachemys because it only has one mark (Souza et al., 2000). It cannot be assigned to Kinosternidae because it does not present a vermiform ornamentation (Cadena et al., 2007) nor elevated imprints of the ninth and tenth marginals (Preston, 1979). The vertebrae did not have morphological features that helped with the identification.

Pleistocene amphibians and reptiles

Amphibian and reptile remains from Loltún cave are here described finding six new taxa for this site: Ctenosaura defensor, C. (Loganiosaura) sp., Boa sp., Lampropeltis, Leptophis and Trachemys (Table 3). Ctenosaura defensor, C. (Loganiosaura) sp. and Leptophis are here reported for the first time for the Pleistocene in México and North America. Nowadays, C. (Loganiosaura) sp. is not found in the Yucatán peninsula. For the Pleistocene herpetofauna of southern México, Loltún cave is now the most studied site.

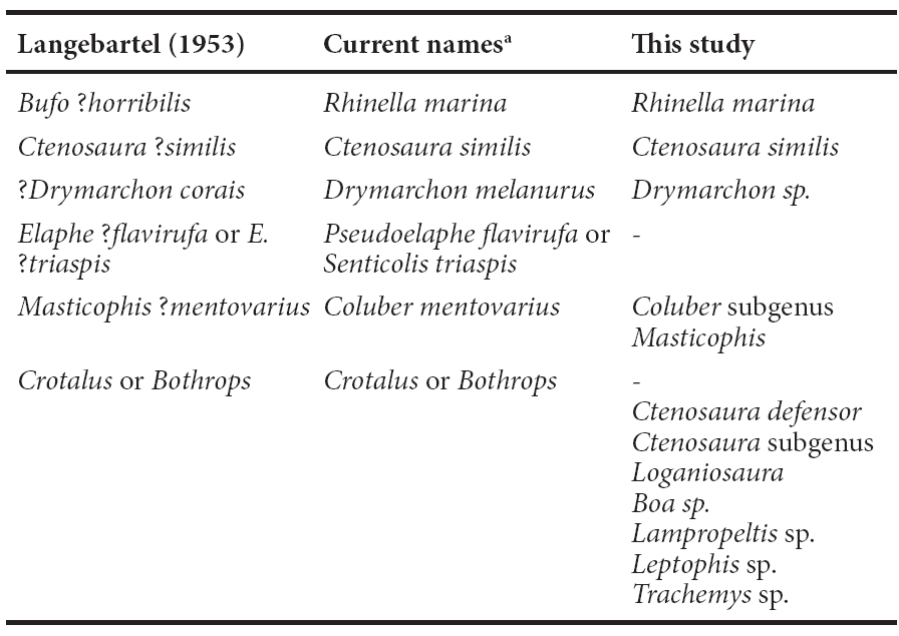

Table 3 Taxa from the Pleistocene of the Loltun Cave. a Current names taken from Uetz et al. (2015).

Paleoclimatic and paleoenvironmental reconstruction

The habitat types that have the highest score (1.9) obtained by the habitat weightings method are evergreen seasonal forest (ESF), tropical deciduous forest (TDF) and scrub forest (SF) (Table 4), suggesting that these habitat types were found at the study site during the Late Pleistocene. This mosaic differs from the vegetation structure of tropical semi-deciduous forest (TSDF) found today in the Loltún cave (Correa-Metrio et al., 2011) and indicates that the paleoenvironment for Loltún cave had a vegetation mosaic not analogous with the present one.

Table 4 Habitat weighting analysis using amphibians and reptiles assemblage from Loltún cave, Yucatán. TRF, tropical rainforest; ESF, evergreen seasonal forest; TSDF, tropical semi-deciduous forest; TDF, tropical deciduous forest; SF, scrub forest; MS, montane systems.

The inferred paleoclimate for the Late Pleistocene in Loltún cave indicates climate conditions proper of the north and west part of the Yucatán peninsula with ESF, TDF and SF habitat types. This shows that for the Late Pleistocene, older than 32782 ± 296 cal yrs BP, Loltún cave had a MAT of 25.33 ± 0.47 °C and an MAP of 1,183.74 ± 143.35 mm.

These values when compared with the values given by Oxcutzcab weather station suggest that the MAT during the Late Pleistocene was -1.47 °C lower and the MAP was 85.14 mm higher than today conditions (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Loltún cave is an important site in southern México, where 12 taxa of Pleistocene amphibians and reptiles have been found and described (Langebartel 1953; this study). A fewer taxa have been described in other places, for example, in Tabasco, one turtle (Luna-Espinoza and Carbot-Chanona, 2009); in Chiapas, three turtles (Luna-Espinoza and Carbot-Chanona, 2009); in Oaxaca, two turtles (Cruz et al., 2009), and in Veracruz, one turtle and a crocodile (Peña-Serrano et al., 2004).

The results suggest a paleoenvironment composed of a vegetation mosaic, different of the present one, with three habitat types: evergreen seasonal forest (ESF), tropical deciduous forest (TDF), and scrub forest (SF). Vegetation communities non-analog with the present ones have been reported in Petén Itza lake, in the Yucatán peninsula (Correa-Metrio et al., 2012a, 2012b), which agree with our findings.

The paleoclimate reconstruction infers a MAT 1.47 °C lower and an MAP 85.14 mm higher than the present one. Since 65 ka BP to LGM (22 ka), Correa-Metrio et al. (2012a) suggest that the MAT decreased 1.5 °C compared with today. Periods of lower humidity occurred during the Heinrich Stadials (Correa-Metrio et al., 2012a) suggesting that the period of the fossil remains in Loltún cave is an interglacial before the LGM (Correa-Metrio et al., 2012a).

The distribution of Ctenosaura subgenus Loganiosaura suffered changes during the Pleistocene. Today, Loganiosaura is found in tropical rainforest areas (TRF) and montane systems (MS) (Köhler, 2003). This study shows that in the past this species could be found in Loltún cave, 446.4 km further to the north than its present distribution (Figure 7). This range shift has been found also for the skunk (Mephitis macroura) and the wolf (Canis lupus) (Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003) that, like Loganiosaura, are not found today in the Yucatán peninsula (Sosa-Escalante et al., 2014). During the Late Pleistocene, Mephitis macroura and Canis lupus were found 489.78 km and 714.94 km further northeast (García-Moreno et al., 1996; Hwang y Larivière, 2001) (Figure 7). The changes in the distribution of these species could be caused by the isotherm displacement which is calculated for the region between 179 to 250 m/yr for the 38-29 ka time interval (Correa-Metrio et al., 2013).

Figure 7 Present distribution of Ctenosaura subgenus Loganiosaura (black area), Mephitis macroura (grey triangles), historic distribution of Canis lupus baileyi (grey stars) and their changes in distribution during the Late Pleistocene in Loltún cave (gray point). Distance of changes are shown as dotted line for Ctenosaura subgenus Loganiosaura, gray line for Mephitis macroura and bold line for Canis lupus baileyi. Habitat types found in the Yucatán peninsula and Central America: tropical rainforest (TRF), evergreen seasonal forest (ESF), tropical semi-deciduous forest (TSDF), tropical deciduous forest (TDF), scrub forest (SF) and montane systems (MS). Modified map from Correa-Metrio et al. (2011).

CONCLUSIONS

The Loltún cave is now the most studied site of southern Mexico because of amphibian and reptile fossils found there. In Loltún cave, the herpetofaunal community is a good paleoenvironment and paleoclimate indicator for the Late Pleistocene and shows a decrease in the MAT, and an increase in the MAP, suggesting an interglacial period before the LGM. In the past, the habitat type was a mosaic vegetation composed of evergreen seasonal forest (ESF), tropical deciduous forest (TDF), and scrub forest (SF). The paleoenvironment for Loltún cave shows a mixture of habitat types, not found today in the area. Climate and vegetation composition changes during the Late Pleistocene could have affected the distribution of Ctenosaura subgenus Loganiosaura and of other species, such as mammals.

Implementing the MCR method, using amphibians and reptiles as paleoclimatic proxies, allowed us to compare and evaluate this method, and to find trends of past climates and how they affect different organisms. It is the first time that a paleoclimatic reconstruction using amphibians and reptiles in a tropical region is made using the MCR method. Our results are in concordance with other paleoclimatic inferences using fossil pollen as a proxy, extending the use of the MCR method to different climatic regions.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)