Highlights

For more than 100 years S. demissum has been used in potato breeding.

14 genes for vertical resistance to late blight have been identified.

Resistance to insects, nematodes, bacteria, viruses and frost damage has been documented for this species.

The presence of bioactive compounds of interest to industry has been also reported.

Introduction

Crop wild relatives are plant species that are closely related to cultivated plants and constitute a huge reservoir of genetic diversity that can be used to breed new crop varieties resistant to diseases, pests and abiotic stresses, with the potential to contribute to food security in the face of climate change and population growth (Fonseka, Fonseka, & Abhyapala, 2020). In the specific case of cultivated potato (Solanum tubersoum L.), its wild relatives (Solanum spp.) are species of great interest, since they carry useful genes for the genetic improvement of this crop (Tiwari et al., 2013). To date, 151 wild potato species distributed in 16 countries in the Americas are known (Spooner et al., 2019; https://cipotato.org/potato/wild-potato-species).

Among the wild relatives of potato, Solanum demissum Lindl. has been, for more than 100 years, one of the most valued and used species for potato breeding due to its richness in genes for resistance to potato late blight (Phytophthora infestans [Mont.] de Bary.). Fourteen vertical resistance genes have been identified, some introduced in commercial varieties, for which it is considered that about 50 % of the commercial varieties in the world have genes of this species (Enciso-Maldonado, Lozoya-Saldaña, Díaz-García, & López-Salazar, 2021; Lozoya-Saldaña, 2011; Paluchowska, Śliwka, & Yin, 2022; Rodríguez, 2015).

During the 19th and 20th centuries, different collections were made around the world, and from the 20th century, scientists focused on making crosses between S. demissum and S. tuberosum to obtain resistant cultivars (Turner, 2005); S. demissum was subsequently used to identify physiological races of P. infestans (Black, Mastenbroek, Mills, & Peterson, 1953; Malcolmson & Black, 1966), and it has demonstrated resistance to insects, viruses, bacteria, and nematodes (Bachmann-Pfabe, Hammann, Kruse, & Dehmer, 2019; del Rio & Bamberg, 2020; Eraso-Grisales, Mejía-España, & Hurtado-Benavides, 2019; Fürstenberg-Hägg, Zagrobelny, & Bak, 2013; Hidalgo-Gómez, Carrillo-Salazar, Rojas-Martínez, Rivera-Peña, & Ayala-Garay, 2022; Lambers, Chapin, & Pons, 2008; Tingey, 1984; Vega & Bamberg, 1995; Zoteyeva, Chrzanowska, Flis, & Zimnoch-Guzowska, 2012). In addition, high antioxidant activity has been detected (Friedman, 2006; Hale, Reddivari, Nzaramba, Bamberg, & Miller, 2008), as well as glycoalkaloids, compounds mainly found in Solanum spp., and which have been found to be useful in plant defense and against human diseases (Friedman, 2006; Kuc, 1992; Manrique-Carpintero, Tokuhisa, Ginzberg, Holliday, & Veilleux, 2013).

The objectives of this review were to summarize the research contributions on the use of the species S. demissum in the genetic improvement of the cultivated potato, as well as its potential uses in other areas, and to highlight the areas of opportunity and limitations of breeding for resistance to late blight so that the review can serve as a starting point for the development of new research or lines.

Methodology

A bibliographic search was conducted in specialized databases, both scientific and technical, including the Centro de Información Científica del CONACYT (https://cicco.conacyt.gov.py/), Google (https://www.google.com/webhp?hl=es-419&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjU04Os9YfxAhVJJrkGHUopCQcQPAgI), Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.es/schhp?hl=es), Web of Science (https://mjl.clarivate.com/search-results), web pages of state institutions, and web pages of international entities related to potato plant genetic resources, among others.

First, keywords and connectors were combined to conduct the search in all fields: "Solanum demissum", "late blight", "Phytophthora infestans", "abiotic stress", "insect resistance", "frost resistance", "wild potatoes", and "resistance genes", with results being obtained from 1848 to 2022. Inclusion criteria such as year (period 1845-2022) and language (English, Spanish) were used. Subsequently, all technical and scientific materials available in these databases concerning the origin, distribution, characterization, resistance to biotic and abiotic factors, and chemical analyses related to S. demissum were selected.

Origen and distribution of Solanum demissum

Solanum demissum, a wild potato belonging to the family Solanaceae (section Petota of the genus Solanum) (Spooner & Hijmans, 2001), is a tall plant with a height of 60 cm, violet to purple flowers, white to tan tubers, round to compressed, and 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1) (Hidalgo-Gómez et al., 2022). It can multiply sexually through the seeds contained in the fruits, resulting in heterogeneous offspring, since it is a self-incompatible hexaploid species (2n = 6x = 72, with an endosperm balance number [EBN] of four) (Spooner & Hijmans, 2001), which gives rise to a complex and wide genotypic variability. This was first described by John Lindley (1848) in the article Notes on the Wild Potato, published in The Journal of the Horticultural Society of London. In this paper, the author describes accessions of S. demissum, collected in the Toluca Valley and Michoacán (Mexico), as plants that produce many runners and few tubers, and emphasizes that the species shows no symptoms of "the disease".

Figure 1 Solanum demissum cultivated in the Toluca Valley: A) flowers, B) plants, C) plant, D) flowers, E) fruits and F) seeds.

The main center of wild potato distribution is in South America, in the Andean region between Peru, Bolivia and Chile (Spooner et al., 2019), while Mexico is considered the second largest center of biodiversity for these species (Lozoya-Saldaña, 2005). S. demissum is distributed in Mexico and Guatemala (Figure 2). The greatest abundance and diversity is found in Mexico, in the Volcanic Axis and the Sierra Madre del Sur, between latitudes 19 and 21°, where the climate is temperate, sub-humid, and with summer rainfall of 800 to 900 mm annually, high relative humidity and thermal oscillation from 12 to 20 °C (Hijmans, Spooner, Salas, Guarino, & de la Cruz, 2002; Lozoya-Saldaña, 2005; Luna-Cavazos, Romero-Manzanares, & García-Moya, 2012; USDA Germoplasm Resources Information Network [GRIN, https://www.ars-grin.gov/]). Spooner, Martinez, Hoekstra, and van den Berg (1997) indicate that S. demissum is a species that usually grows only in shady places under mature trees, among moss or pine litter.

Figure 2 Geographic distribution of Solanum demissum. Map generated from the data of Hijmans et al. (2002) and USDA-GRIN (https://www.ars-grin.gov/).

Late blight resistance

Interest in collecting and studying wild potatoes grew out of the Irish potato famine, also known as the Great Famine, which occurred in the 1840s. In it, potato monocultures in Ireland were devastated by "the disease", now known as late blight, caused by the oomycete P. infestans, which caused a major food crisis resulting in severe food shortages and loss of human life due to starvation and malnutrition (Fry et al., 2015; Majeed, Siyar, & Sami, 2022; O'Neill, 2009; Schoina & Govers, 2014). After this event, through several European expeditions, genotypes of the potato’s wild relatives were collected for crossing with the edible species in order to obtain resistant varieties (Hawkes, 1941). Edible potato varieties, at that time, were obtained through intraspecific crosses of a limited number of S. tuberosum genotypes, which generated a narrow genetic base that was easily overcome by the oomycete (Turner, 2005).

The oomycete P. infestans is one of the most studied pathogens in phytopathology; however, it remains a subject of research because it continues to cause major epidemics in potato and tomato crops worldwide (Fry et al., 2015). Until the mid-20th century, plant breeders believed that crosses between European varieties of S. tuberosum and their Mexican wild relatives would result in potato offspring resistant to late blight; however, Dr. Salaman at Cambridge would demonstrate the heritable nature of the resistance of a wild species (S. endinense) and initiated the first crosses between S. tuberosum and S. demissum (Black, 1954; Turner, 2005). Donald Reddick at Cornell University undertook a plant-exploring expedition to the mountains of Mexico (Reddick-Retires, 1951), where variability and indications of resistance to late blight sparked particular interest in studying Mexican wild potatoes (S. bulbocastanum, S. pinnatisectum, S. hjertingii, S. papita, S stoloniferum, S. polyadenium, S. verrucosum and S. demissum, among others) (Enciso-Maldonado et al., 2022; Zoteyeva et al., 2012; Song et al., 2003).

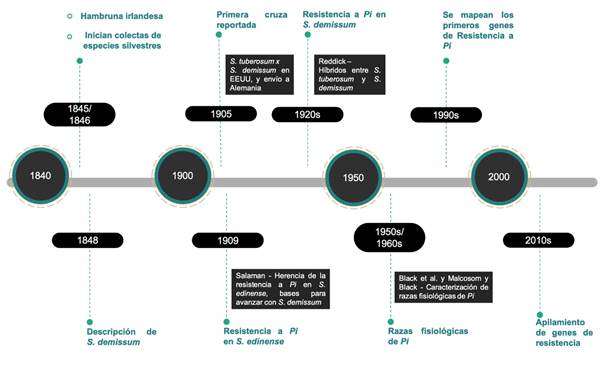

Currently, the most important center of diversity of P. infestans is considered to be in the Toluca Valley, extending into Michoacán and Tlaxcala, where there is a metapopulation of the pathogen that could contribute to the repeated resurgence of P. infestans in the United States and elsewhere (Wang et al., 2017). In this regard, Mexican species are believed to have co-evolved with the pathogen over millions of years and have acquired a natural resistance to it (Alfaro, 1995), with S. demissum being one of the most studied species in the last 100 years (Figure 3) because it has vertical resistance genes (Enciso-Maldonado et al., 2021; Lozoya-Saldaña, 2011; Paluchowska et al., 2022).

Figure 3 Chronology of the use of Solanum demissum in potato breeding for resistance to late blight (Phytophthora infestans). Source: author-made.

One of the most important contributions that has been made with S. demissum is the identification of physiological races of P. infestans, since this oomycete can present different levels of virulence, with which it can overcome host resistance and cause the disease; furthermore, as mentioned above, S. demissum carries resistance genes. Genetic resistance, in the case of P. infestans-wild potato species interaction, can be explained by the gene-to-gene model, where for each host resistance gene there is a specific gene that determines the pathogenicity or virulence of the pathogen (Flor, 1959). Therefore, the plant’s resistance gene is only effective if there is a corresponding avirulence gene in the pathogen (Alvarez-Morezuelas, Alor, Barandalla, Ritter, & de Galarreta, 2021; Serrano & Cádenas, 2008).

Black et al. (1953) and Malcolmson and Black (1966) inoculated different races of the pathogen in host plant differentials, with which they compared the immunity genes present in the host series and, from this, formulated a nomenclature system suitable for international application. In this way, they evaluated the virulence spectrum, which is the range of Avr genes expressed by the isolate when inoculated in the differential series of genotypes with R resistance genes. When isolates with the same virulence spectrum were observed, they were called physiological races, and the broader the virulence spectrum, the more complex was the race of the pathogen considered to be (Alvarez-Morezuelas et al., 2021). In this regard, Black et al. (1953) describe that race 1, 2 is capable of causing disease in genotypes carrying resistance genes R1, R2 or R1-R2, but does not thrive in the presence of R3 or R4 genes. Therefore, susceptibility is only possible when the race has in its designation all the numerals present in the plant genotype. Consequently, the R1-R2 genotype, which is the natural host for races 1, 2, is susceptible to races 1, 2; 1, 2, 3; 1, 2, 4 and 1, 2, 3, 4, and is only immune to the rest.

Black's differentials are used to this day to characterize P. infestans isolates into pathotypes or physiological races based on their virulence in plants with R genes from a differential group of genotypes (Alvarez-Morezuelas et al., 2021). Thanks to studies by Black et al. (1953) and Malcolmson and Black (1966), research was initiated to introduce the late blight resistance genes contained in S. demissum into potato cultivars, which were used by farmers for years.

Starting in the 2000s, the term effector began to be used and related to the term avirulence (Hogenhout, Van der Hoorn, Terauchi, & Kamoun, 2009). Effectors are defined as "all pathogen proteins and small molecules that alter host-cell structure and function", and whose alterations facilitate infection or trigger the plant's defense response (Hogenhout et al., 2009; Kamoun, 2007). The effectors present in P. infestans have been extensively studied and are broadly classified into apoplastic effectors and cytoplasmic effectors, although further classifications can be found in recent studies. The former are small cysteine-rich (SCR) proteins, such as PcF proteins (formerly called phytotoxins), a family of necrosis- and ethylene-inducing proteins (NLPs), and inhibitors of enzymes and extracellular proteases that degrade host structures, while cytoplasmic effectors are a family of RXLR proteins and CRN proteins (Fabro, 2022; Kamoun, 2006; Saraiva et al., 2022).

RXLR-type effector genes have been extracted from the P. infestans sequence and used in gene expression assays in wild potato species, with the aim of finding avirulence activity and accelerating the cloning of R genes (Lokossou, et al., 2009; Saunders et al., 2012; Schornack et al., 2009; Vleeshouwers et al., 2008). Several NLR genes (associated with effector-triggered immunity [ETI], most of which belong to the CC-NLR family) have been identified, with R3a from S. demissum and Rpi-blb2 from S. bulbocastanum (recognizing the RXLR effectors AVR3a and AVRblb2, respectively) being of great interest, as they accentuate the importance and usefulness of effector studies in the search for and cloning of resistance genes (Majeed et al., 2022; Saraiva et al., 2022).

To date, 14 functional late blight resistance genes have been found in S. demissum: R1, R2, Rpi-demf1, R3a, R3b, R4 al , R4 MA , R5, R6, R7, R8, R9a, R10 and R11. Of these, the R1, R2, R3a, R3b, R8 and R9 genes have been cloned and classified within the family of genes encoding nucleotide- binding site and leucine-rich repeat domain-containing proteins (Paluchowska et al., 2022). Molecular cloning of genes has facilitated studies at the molecular level for the management of potato late blight resistance, as these can be used in genetic engineering to develop resistant cultivars (Rogozina, Beketova, Muratova, Kuznetsova, & Khavkin, 2021). However, these genes have not yet been widely introduced into potato cultivars, partly due to crossing difficulties arising from the difference in ploidy (Bethke, Halterman, & Jansky, 2017).

The ongoing coevolution of pathogen effectors and plant R genes represents the so-called arms race between plants and pathogens (Khavkin, 2015; Saraiva et al., 2022).

Insect resistance

Solanum demissum has been shown to be resistant to pests such as the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) and the potato leafhopper (Empoasca fabae) (Fürstenberg-Hägg et al., 2013). Resistance to the Colorado potato beetle is positively associated with the high content of the glycoalkaloids chaconine, demissine and leptines (Kuc, 1992), secondary metabolites known to act as a chemical defense against certain pathogens, although they are potentially harmful in humans (Eraso-Grisales et al., 2019; Lambers et al., 2008; Tingey, 1984). A limitation in obtaining insect-resistant genotypes of S. tuberosum is based on the fact that the offspring of resistant hybrids between S. tuberosum and S. demissum produce tubers with a high glycoalkaloid content.

Nematode resistance

Potato cyst nematodes, Globodera pallida and G. rostochiensis, make up an economically important group for potato cultivation. Their cysts can survive for more than 10 years in the soil, and persist even under unfavorable environmental conditions and the application of nematicides (Dandurand et al., 2019). Bachmann-Pfabe et al. (2019) identified genotypes resistant to nematode infection in 15 of 67 S. demissum accessions evaluated, and 45 of 67 with partial resistance. In addition, they indicate that the resistance of accessions originating in Mexico could be due to the presence of G. mexicana in Mexico, which is closely related genetically to G. pallida.

Resistance to other infectious agents

In the potato program of the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP), in Metepec, State of Mexico, S. demissum was found to present some resistance to the bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum, so it could be included in breeding programs to mitigate the effects of this microorganism (Hidalgo-Gómez et al., 2022).

On the other hand, a screening of wild species carried out by Zoteyeva et al. (2012) showed that S. demissum exhibits resistance to potato virus X (PVX) and potato virus Y (PVY), which is part of the Bulgarian potato breeding program (Masheva, 2014). However, although Tiwari, Jeevalatha, Tuteja, and Khurana (2022) stress that the S. demissum Ny dms gene confers a hypersensitive response (HR) against PVY and potato virus A (PVA), traditional breeding has not been entirely effective due to the rapid evolution of virulent strains (same case as late blight), making it important to use new technologies such as CRISPR-Cas (Doudna & Charpentier, 2014) for the generation of resistance by disruption of host factors or interference in the viral genome.

Frost resistance

Unlike pest and disease management, frost is not easily managed with cultivation practices or chemical treatments; therefore, the use of resistant varieties is recommended to reduce losses due to frost (Vega & Bamberg, 1995). S. demissum is classified, within the group of wild relatives of potato, as one of the most frost-resistant species, withstanding up to -2 °C (Vega & Bamberg, 1995). Since the beginning of the 20th century, this has led to the obtaining of frost-resistant hybrids from crosses between S. demissum and S. tuberosum (del Rio & Bamberg, 2020).

Other properties

Glycoalkaloids, widely studied secondary metabolites, are commonly found in potato and its wild relatives, and have been classified as toxic compounds, making them useful in defending against pathogen attack and certain human diseases (Friedman, 2006; Friedman, McDonald, & Filadelfi-Keszi, 1997; Kuc, 1992; Manrique-Carpintero et al., 2013). High concentrations of (-tomatine, demissine, demissidine, tomatidine, chaconine, and tomatidenol have been found in S. demissum (Distl & Wink, 2009; Friedman et al., 1997); the last has been introgressed into S. tuberosum (McCue, 2009). These compounds have shown an effect in the treatment of different diseases, as they have been associated with anti-inflammatory, antihyperglycemic, antibiotic, anticholesterolemic and anticancer properties (Friedman, 2006; Milner et al., 2011). Tomatidine inhibits the growth of colon and liver cancer cells in vitro (Wölfling, 2007), (-chaconine and (-tomatine have a positive effect on the inactivation of herpes virus type 1 (Thorne, Clarke, & Skuce, 1985), and (-tomatine inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in myeloid leukemia cells (Huang et al., 2015).

In wild potato species, including S. demissum, high antioxidant activity has been reported, and phenolic compounds such as p-coumaric acid, chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid have been found. The last has antioxidant, antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal and anti-inflammatory properties (Butiuk, Martos, Adachi, & Hours, 2016; Eroglu & Dogan, 2023; Friedman, 2006; Hale et al., 2008).

Discussion

Solanum demissum is an important phytogenetic resource, valued for its resistance to pests and diseases, positioning itself on the map as one of the most exploited wild relatives of potato in breeding programs. However, despite the fact that genes for resistance to blight and other stress factors have been one of the most studied aspects in the last 100 years (by obtaining countless cultivars resistant to late blight), the results obtained from traditional breeding have not been entirely successful. P. infestans and other pathogens have managed to evade the genetic resistance of cultivars obtained through crosses with S. demissum, which has led to the development of new epidemics worldwide, such as in the United States, Canada, India, Mexico, Peru, the vast majority of European countries, Africa and Asia (Fry et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2014; Dey et al., 2018; Romero-Montes, Lozoya-Saldaña, Mora-Aguilera, Fernández-Pavia, & Grünwald, 2012; Zoteyeva & Patrikeeva, 2010; Forbes, 2015).

As a result of the above, it is essential to continue researching, discovering and proposing improvements through the use of new technologies to make breeding programs more efficient. Currently, there are two aspects in the application of these tools: the search for and identification of candidate genes in S. demissum, and the introgression of the discovered genes into S. tuberosum.

For gene searching and identification, knowing the diversity, structure and relationships of the germplasm, genotyping by sequencing (GBS), genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and QTL's, to mention a few examples, are useful tools that can facilitate and accelerate the localization and selection of genes of interest, which will then be sought to be introduced or silenced in cultivated potato. Several studies have documented the feasibility of using these tools (Bastien, Boudhrioua, Fortin, & Belzile, 2018; Boudhrioua et al., 2017; Bradshaw, Hackett, Pande, Waugh, & Bryan, 2008; Hackett, McLean, & Bryan, 2013; Okada et al., 2019; Prodhomme et al., 2020; Rosyara, de Jong, Douches, & Endelman, 2016; Saidi & Hajibarat, 2020; Uitdewilligen et al., 2013; Zhang, Qu, Gu, Xu, & Xue, 2022). Some examples of genes that may be of interest are the late blight resistance genes (already mentioned above), the GBBSI gene (associated with amylose), the Asn1, Asn2 and Vlnv genes (associated with acrylamide accumulation), the polyphenol oxidase gene (responsible for browning) and the beetle β-actin gene.

Regarding gene introgression into S. tuberosum, genetic transformation was the first strategy used, where the main methods are bio-ballistics, protoplast fusion and Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Díaz-Granados & Chaparro-Giraldo, 2012). Bio-ballistics consists of the bombardment of microprojectiles covered with the DNA to be transferred, which carries, inside the cell, the genes of interest that will later be integrated into the plant genome. Protoplast fusion is a chemical-mediated transfer that most commonly uses polyethylene glycol to induce membrane permeability to allow the DNA to pass into the cell. The Agrobacterium system works because of the genus' ability to infect plant organisms and transfer DNA, and involves using the organism as a vector for gene transfer to the plant. This transformation can be trans-genesis or cis-genesis. The latter is used in the case of S. demissum and S. tuberosum, as they are closely related species (del Mar Martínez-Prada, Curtin, & Gutiérrez-González, 2021; Díaz-Granados & Chaparro-Giraldo, 2012; Nadakuduti, Buell, Voytas, Starker, & Douches, 2018; Nicolia, Fält, Hofvander, & Andersson, 2021; Toinga-Villafuerte, Vales, Awika, & Rathore, 2022; Van Eck, 2018; Zhang, Zhang, & Chen, 2020).

The second strategy used for introgression is gene editing. Zinc finger nucleases (ZFN), TALEN nucleases and the CRISPR-Cas9 complex are useful methods and another alternative for the use and introduction of genes of interest from S. demissum (Van Eck, 2018). Some reviews and trials have shown successful cases with the use of TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9 in S. tuberosum, such as the reduction of glycoalkaloids in tubers, resistance to herbicides, starch quality in tubers, self-incompatibility, and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity in tubers to reduce enzymatic browning.

The generation of genetically modified varieties produced and marketed since 1995 (NewLeafTM, NewLeafTM Plus, NewLeafTM Y, Innate® 1.0 Innate® 2.0, AmfloraTM, Starch potato, Elizaveta Plus, Lugovskoi Plus, SpuntaG2, Desiree, Ranger Russet, Taedong Valley, King Edward, Chicago, Atlantic, Kuras, Sayaka and Mayqueen) include cis-genesis, CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN genetic transformation approaches, where acquired traits include incorporation of resistance to the Colorado potato beetle, PVY and late blight, reduction of acrylamide, glycoalkaloids, black spot and amylose, and an increase in TAG, carotenoids and vitamins (Abdallah, Hamwieh, Radwan, Fouad, & Prakash, 2021; del Mar Martínez-Prada et al., 2021; Hameed, Zaidi, Shakir, & Mansoor, 2018; Nadakuduti et al., 2018; Tiwari et al., 2022; Tussipkan & Manabayeva, 2021; Yasumoto et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2015).

Techniques such as gene silencing (RNAi) (used to confer resistance to viruses such as PVY, PVX, PVS, PLRV and late blight) (Del Mar Martínez-Prada et al., 2021; Hameed et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2016) or gene blocking (gene knockout, suggested as an effective strategy to reduce acrylamide content) (del Mar Martínez-Prada et al., 2021), used in conjunction with CRISPR-Cas9, have proven to be successful and have provided an interesting basis for further studies on gene functionality (Clasen et al., 2016; Kieu, Lenman, Wang, Petersen, & Andreasson, 2021; Toinga-Villafuerte et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2015).

From the wide possibilities for the application of transformation and gene editing tools, two major challenges have been visualized; on the one hand, there is the complexity represented by the variability of ploidy between species and, on the other, the government regulations imposed and in process for genetically modified organisms (Van Eck, 2018).

On the other hand, the antioxidant properties and the presence of glycoalkaloids in S. demissum set a starting point in agricultural and pharmaceutical research to take full advantage of these resources. Work has been carried out on the extraction of glycoalkaloids in cultivated potato (mainly (-chaconine and (-solanine), and different extraction methods have been proposed, such as aqueous extraction, obtaining acidified ethanolic extracts, obtaining extracts with ammonium hydroxide. and extraction with pressurized liquids (Eraso-Grisales et al., 2019; Sánchez-Maldonado, Mudge, Gänzle, & Schieber, 2014; Silva-Beltrán et al., 2015). In addition, the effectiveness of the extracts of these compounds against bacterial strains such as E. coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Listeria ivanovii and Staphylococcus aureus has been evaluated, as well as the biocidal effect against snails and the Colorado potato beetle (Kuc, 1992; Silva-Beltrán et al., 2015).

Regarding antioxidant activity, particularly for the extraction of p-coumaric acid, chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid (present in S. demissum and whose properties were described above), it may be feasible to use methodologies proven in other crops, such as artichoke or coffee, in which alcoholic, hydroalcoholic extracts and acid hydrolysis with hydrochloric acid are used (Eroglu & Dogan, 2023). Likewise, methodologies can be considered to determine the most suitable solvent for the extraction of the compounds (Aristizábal, Vargas, & Alvarado, 2019; Gani et al., 2006; Ky, Noirot, & Hamon, 1997).

Finally, it is worth emphasizing the importance that S. demissum has had over the years, being a milestone in the genetic improvement of potato, and contributing to the understanding of resistance and the identification of physiological races. S. demissum has been the focus of a large number of research projects, and today it has the known properties and elements to continue contributing to the improvement of crops and the production of useful compounds for humans.

Conclusions

Solanum demissum is one of the species with great potential in different areas and for potato breeding. Traditional breeding has limitations that could be solved with the use of new molecular technologies, which, when used in an integral way, would result in an important advance in the field of improvement and use of plant species.

texto en

texto en