Introduction

In Andalucía, the dehesas, a representative savanna-like ecosystem type, comprise vast land areas (1 263 143 ha, a third part of the total coverage), and also in other Spanish counties (mainly Extremadura, Castilla-La Mancha and Castilla-León), and in Portugal (known as montados) (Silva and Ojeda, 1997; Silva, 2010). This ecosystem, that derives from a long history of human transformation of Mediterranean forests through clearing, browsing and ploughing to provide food for livestock rearing, are composed of an overstorey of scattered oaks (mainly holm-oak and secondary Q. suber L. cork oak), at 20 trees/ha - 30 trees/ha, and an annual grasslands layer (Leiva, Mancilla-Leytón and Martín-Vicente et al., 2015). Shrubs interspersed in the grassland matrix may also occur but they are usually confined to less transformed and intensively grazed patches, usually dedicated to wild game. This ecosystem is not only one of the most representative landscapes of the Iberian Peninsula (3.3 million of hectares - 3.5 million of hectares, according to the Second National Forest Inventory) of great aesthetical, recreational and cultural value (Leiva et al., 2015), but it also shows great relevance regarding the way its resources can be used, favoring production and conservation jointly (Fernández-Alés, 1999; Costa, Martín-Vicente, Fernández-Alés and Estirado et al., 2006). It is a multifunctional exploitation system (agro-forest-pastoral), highly sustainable (scarce inputs and few residues), with which some human communities of the western and southwestern part of the Iberian Peninsula have responded to a set of geoedaphic, biogeographic, economic and social circumstances (Martín-Vicente and Fernández-Alés, 2006). The dehesa plays an important economic, ecological and social role, since, besides providing agricultural, livestock and forest productions to maintain some stable populations and the market, it also performs a set of environmental services such as the conservation of biodiversity (habitat for many species and communities of flora and fauna), the regulation of the water and carbon cycles, protection of soil against erosion or forest fire prevention by acting as firewalls (Costa et al., 2006; Anaya-Romero, Muñoz-Rojas, Ibáñez and Marañon, 2016).

Between the 60s and 80s there was a decrease of the land area assigned to dehesas due to the swine fever, the abandonment of rural habitat and the increase of new ways of agricultural production (Martín-Vicente and Fernández-Alés, 2006). In the last decade, what remains from this ecosystem is in decay and the need for improving the regeneration of trees in the dehesas is an imperative feature acknowledged by the administrations, and it is considered in the recent Andalusian regulations (Law 7/2010, of 14th July, for the Dehesa, BOJA 144), in the less recent regulations of Extremadura (Law 1/1986, of 2nd May, about the Dehesa in Extremadura) and in the background documents for planning the management of the dehesas at a ministerial level (Pulido et al., 2010).

One of the main signs of this decay is the alarming lack of regeneration of trees in a large part of the dehesas of the national territory, with populations of old holm oaks where young individuals are scarce or do not exist (Siscart, Diego and Lloret, 1999; Pulido and Díaz, 2005; Leiva et al., 2015). This phenomenon, due mainly to the rural exodus, which involves the abandonment of the exploitation management, and to the lack of maintenance abilities and skills (“loss of the traditional know-how-to”), becomes worse by the impact of health problems in the trees (“forest decay syndrome” or “drying”) which affects many of the dehesas in Andalusia and other counties (see Natalini, Alejano, Vázquez-Piqué, Cañellas and Gea-Izquierdo, 2016) and endangers the persistence of these systems at the medium and long term. However, the probable impact that these processes may be causing on the evolution of the spatial occupation of the dehesa (its reduction, expansion or territorial stability) in a certain region has not been considered in detail, perhaps due to the difficulty of integrating both study scales.

The present Law of the Dehesa in Andalusia promotes the development of a clear and recent diagnosis of the problems that could set the guidelines for its conservation, regeneration and spreading of its environmental values. Given this imperative need, and there are few studies focused on this issue, it is necessary to evaluate and know the temporal dynamics of the use of holm oak area land in the last few decades. So, in the present study, the temporal dynamics of the land use/cover as dehesa was estimated for the last 50 years, through a diachronic study carried out in Sierra Norte de Sevilla Natural Park (Dehesas de Sierra Morena Biophere Reserve, Spain).

Material and methods

Study área

The study was focused on Sierra Norte de Sevilla Natural Park (37º 40 N, 5º 59 W), western Andalucía (Southern Spain). Sierra Norte de Sevilla Natural Park (177 000 ha), Aracena y Picos de Aroche Natural Park and Sierra de Hornachuelos Natural Park were declared “Dehesas de Sierra Morena” Biosphere Reserve by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco), in November 2002 (Villa and Hernández de la Obra, 2003). It is the largest Biosphere Reserve in the Iberian Peninsula dedicated to the dehesa as a representative landscape of the Mediterranean region. The study area is a mid-mountain region, where dehesas, scrublands, forests and marginal crops create an exceptional mosaic of landscapes. The climate is Mediterranean, with an average annual rainfall between 600 mm and 950 mm and an average annual temperature between 13.4 °C and 17.6 ºC. The rain falls mainly between mid-September and mid-May and it is not significant during the summer.

Analysis of the changing processes of land use /land cover

The spatial analysis of information has recently turned a greatly important aspect in science for the knowledge of natural and/or anthropic phenomena (diagnosis performance; generation of guidelines for zoning; support for decision-making, etc.). The increasing awareness about the adverse effects of the breaking-up of the habitats established on the natural systems has fostered an increasing demand on instruments to predict and evaluate the effect that management projects and important infrastructure constructions may have in the connectivity of the natural world (Adriaensen, Chardon and De Blust, 2003).

The landscapes, as every ecological unit, are dynamic in structure, function and spatial pattern. This dynamic condition of the landscape requires time, or temporal changes, to be considered in the quantitative studies. In this framework of dynamic interrelationships among the economic systems and the environmental and social systems of the dehesa, the use of cartography, and more specifically the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS), has become an instrument of great value (fast and economic) that allows analyzing the changes diachronically.

In order to analyze the temporal dynamics of the land use/cover of the Sierra Norte de Sevilla Natural Park, a diachronic study was carried out. A necessary graphic (maps) and computerized (handling of databases and applications) environment was generated to make it possible to interpret the geographic digital information available, which was named Project ArcMap (Environmental Systems Research Institute [ESRI], 2008).

To make the different maps of changes of use, background cartographic information was employed, which was later processed. For the selection of the borderline of the Sierra Norte de Sevilla Natural Park, the layer of information from Red Natura 2000 in Andalusia was used, in shape format, at a detail and recognition scale (at a scale of 1:10 000, 2008). The Land Use and Land Cover Map of Andalusia (LULCMA) for 1956, 1999, 2003 and 2007 (at a scale of 1:25 000) was used as a base (Moreira, 2007). The LULCMA was a result of the Coordination of Information on the Environment (Corine) programme of the European Commission. Corine project offers stable information on land cover and land cover changes across Europe (Muñoz-Rojas et al., 2015). The special reference systems (coordinates systems, map projections, etc.) used in maps was EPSG 23030 (ED 50 / UTM Zone 30N).

This information, in shape format, was reclassified according to similarity criteria between each one of the uses following the expert bibliography consulted, with the aim of making it easier to handle the information and highlighting the land uses/cover that may be truly interesting in this study. The classification of the forest covers was performed regarding the tree species that were predominant in the uses. The “forest areas and natural wooded areas with predominant dense wooded formations” were grouped according to the three predominant plant species, differentiating: i) Dehesas: forest and natural areas with predomination of some generally long life-cycle species of Quercus; ii) Forests: forest and natural areas with predomination of some middle-short life-cycle species (Conifers and Eucalyptus). In this way, the number of groups of uses was reduced from 112 to 12: urban, communication routes, mining areas, water surface areas, crops, dehesas, scrublands, grasslands, reforestation, all other vegetation, eroded areas and dumping sites (Table 1).

Table 1 Reclassification of land use and land cover types of Andalusia.

* From the Land Use and Land Cover Map of Andalusia (Moreira, 2007)

Results

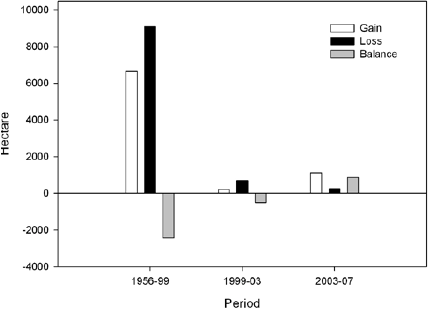

Table 2 and figure 1 show the results obtained from the diachronic analyses of the land use /cover. Together, the great changes of land use occurred between 1956 and 1999, being lower during the last few years (2003 and 2007). The clear, most important changes observed were related to: the increase of urban areas; water surface area; reforestation areas; eroded areas; mining areas and dumping sites; and to the decrease of cultivation areas, dehesas, scrubland and grassland.

Table 2 Gain and/or loss (Ha) of Sierra Norte of Sevilla Natural Park by category of use / vegetation cover the soil in the years 1956, 1999, 2003 and 2007.

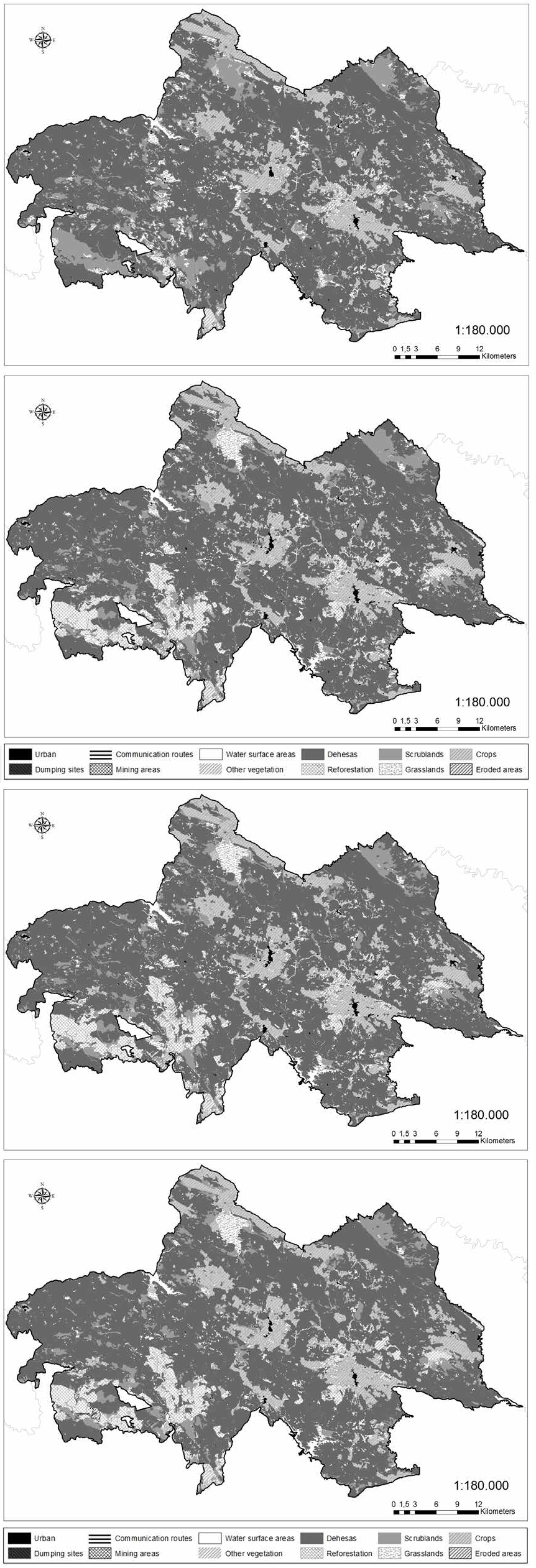

Figure 1 Map of Sierra Norte de Sevilla Natural Park by category of use / vegetation cover soil in 1956 (A), 1999 (B), 2003 (C) and 2007 (D).

Within the period of 1956-1999 urban surface area increased 58% (144 ha), affecting farming and forest areas (Figs. 1A and B). During more recent periods, urban area, far from stopping, was expanding (4% for the period 1999-2003 and 8% for 2003-2007) (Figs. 1C and D). These increments were significant in the main populations of the Park (Cazalla de la Sierra, El Pedroso, Constantina and Las Navas de la Concepción).

The water surface areas include natural and anthropogenic (reservoirs, irrigation ponds...) ecosystems. These zones have experienced an increment of 260% (almost 2000 ha) during the period 1956-1999, and remained practically stable until 2007 (these data must be regarded with caution, as they are likely to vary among seasons) (Table 2). These increments were basically due to a sharp increase of water coverage of reservoirs, caused by the construction of the Huéznar´s Reservoir at the southern region of the Park, and the Retortillo´s Reservoir, southeast, which are added up to the already existing. El Pintao´s Reservoir at the north, affecting the cultivation areas, dehesas, scrubland and pastureland (Fig. 1).

Reforestations (conifers and eucalyptus) show great increase in the period 1956-1999 (8390 ha, approximately an increase of 3250%), from which there was a slight decrease in 2003 (-700 ha), and was established later within the same values of 1999 in 2007 (Table 2). These new reforested tree masses have substituted mostly dehesa and scrubland areas, being this change significant in the southeastern and southwestern areas of the Park (Fig. 1).

The creation of new dumping sites (almost 10 ha), boosted by the increment of urban zones, as well as the increment of eroded areas (especially during the period 1956-2003, more than 900 ha) and the 400% increase of the mining areas (El Cerro del Hierro) from 1956 to 2007, are examples of surface degradation derived from anthropic activities.

The increments of uses were obvious; however, the decreases were even more obvious. As it was previously mentioned, during the period 1956-1999, an important reduction was observed in plant formations such as the scrubland (-6615 ha) and the dehesa (-2443 ha). Likewise, there was also a decrease in the use of crops (-1328 ha). This pattern remains obvious in the period 1956-2003; the loss of land as dehesa becoming even more obvious (-2938 ha) (Table 2; Figs. 1A and B). In the period 2003-2007, the decrease of uses of grassland areas (-1746 ha), cultivation areas (-416 ha) and eroded areas was related to an increase of scrubland areas (1576 ha), dehesa areas (865 ha) and reforestation areas (528 ha) (Table 2; Figs. 1C and D).

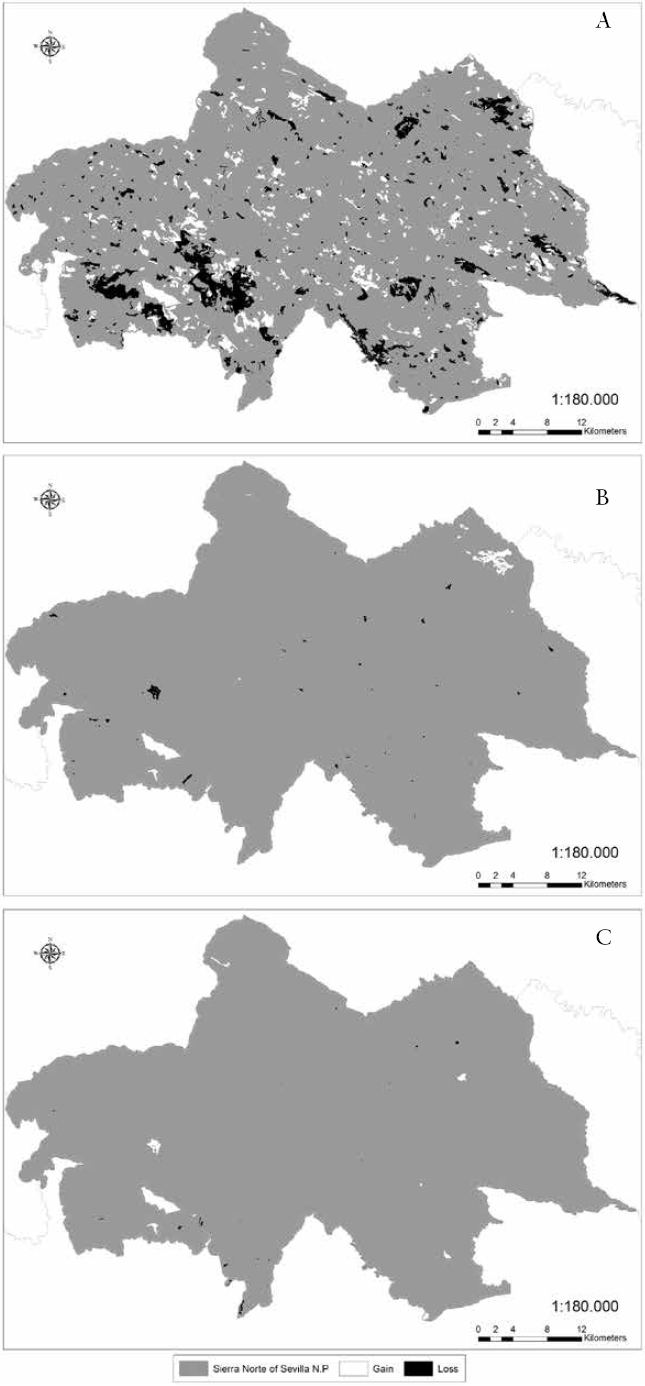

The results obtained allow us to perform a detailed “loss and gain” study for each period (Figs. 2 and 3). If we only focus on the use of the dehesa, the data show an important surface loss with time: 9093 ha in the year 1999 (very obvious in the southeastern and southwestern regions of the Park), 9794 ha in the year 2003 and 10 054 ha in the year 2007 with respect to the land use/cover in the year 1956 (Figs. 2 and 3). However, this loss was balanced with gains (reforestations), which were 6650 ha in the year 1999, 6857 ha in 2003 and 7982 ha in 2007 (very obvious in the northeastern region) with respect to the land use/cover in the year 1956 (Figs. 2 and 3). Therefore, there was a “loss” or negative balance (more than 2000 ha) in the period 1956-2007 (Table 2).

Figure 2 Map of the dynamic of the dehesa of Sierra Norte of Sevilla Natural Park from use / vegetation cover the soil in 1956-1999 (A), 1999-2003 (B) and 2003-2007 (C).

Discussion

The results found in the present study showed that the process of change of land uses, consisting of the abandonment of the primary economic activities and the substitution for residential uses or even the absence of uses, represents the transition of an agricultural model, characterized by the subsistence farming (rain-fed, irrigation or under plastic) and the forest exploitation of wood and wood-fuels (conifers and eucalyptus), to a postindustrial model, typically outsourced (tourism). These processes, together with the current processes of complex environmental change (influence of light, orography, predation, scrubland expansion, senescence, phytosanitary state, etc.) make it very difficult to ensure the persistence of this ecosystem (dehesa).

The Andalusian forest surface has been subjected to many operations since man came to this land; the clearing of forests for the expansion of cultivations, the use of wood to supply the metal industry, the grazing, the extraction of wood for the construction of ships and houses and even the burning of forests in several wars have formed the present forest landscape of Andalucía (Emanuelsson, 2009). The economic development experienced by the western countries in the last 50 years has triggered an important change in land use/cover. In the mid-nineteenth century, as a consequence of the confiscations, the most intense process of forest resource appropriation takes place; more than 430 000 ha of mount were alienated in Andalucía, most of these immediately transformed in order to obtain a quick benefit from wood sales (Ojeda, 2013). The use of the most fertile areas has been intensified, at the same time as the marginal areas have been greatly abandoned, which has changed the structure and functioning of the landscapes (Fernández-Alés, Martín-Vicente, Ortega and Alés, 1992; Grove and Rackham, 2001; Ojeda, 2013). In the first study period, 1956-1999, the crisis of the traditional agricultural system of the mountainous region caused a decrease of the competitiveness of livestock exploitations, structural unemployment, emigration, regression and aging of the population and, consequently, the landscape and environmental change, reflected by the abandonment of the dehesas and cultivation lands, the advance of the scrubland and the appearance of fast-growing forest crops (conifers and eucalyptus) (Ojeda, 2013).

If in this first period traditional exploitation such as improper pruning (charcoaling) and removal of scrubland were the main causes that affected negatively the survival and recruitment of trees in the dehesa (Martín-Vicente and Fernández-Alés, 2006), the modern uses (farming, introduction of crops, as irrigation, intensive livestock breeding, reforestations, construction of new reservoirs...) may be the triggers of the greatest loss of dehesas area until 2003 (also 3000 ha in the period 1956-2003, Table 2), besides being related to the restrictions applied to forest practices in this territory, and perhaps also related to the fact that the investments made in the area were assigned with priority to the tourism sector more than to the recovery of grasslands, dehesas and native vegetation (Álvarez-Carriazo, 2002). Likewise, the abandonment of the marginal, poorly profitable crops and the general depopulation of the rural areas (causing an important urban growth, Table 2), fostered to some extent by the system of community grants carried out in the last few decades, has favored an increase of forest fires, which has resulted in an important decrease of the area occupied by natural vegetation (decreasing scrubland or coppice and dehesa formations, with respect to the previous period studied, while increasing the land occupied by herbaceous formations and reforestations of conifers and eucalyptus).

By last, in the study period 2003-07, the statement of the UNESCO in 2002 “Dehesas de Sierra Morena” Biosphere Reserve has apparently changed this tendency, contributing to a decrease in the uses of grasslands, cultivation areas and eroded areas towards an increase of scrublands, dehesas and reforestation areas, with respect to the year 2003 (Table 2, Fig. 2). This is a change in the concept of landscape, by which dynamism clearly substitutes immobility and landscapes are regarded as life spaces (Ojeda and Silva, 2002; Silva, 2010).

Future Prospects and Implications

In the present study, based on the reported processes of changes of land use/cover, the unidisciplinary interpretations were insufficient for interpreting the current landscape of the dehesa in the interval 1956-2007. The change dynamics does not strictly respond only to phytosociological aspects; it is also necessary to explain the landscape evolution from the complex equilibrium between biophysical and socioeconomic dynamics (Gómez-Aparicio, Pérez-Ramos and Mendoza, 2008).

Many studies state that, within the last few decades, the dehesa has decreased dramatically not only in Andalusia, but also in the rest of the Iberian Peninsula (Silva, 2010; Bugalho, Caldeira, Pereira, Aronson and Pausas, 2011). The dehesa has experienced a change of uses, evolving in most cases through the boost of intensive agriculture, or by the abandonment of agricultural activities and the boost of hunting activities, or through forest cultivation of fast-growth species. Besides the actual loss of land use as a dehesa, the current tree population of the dehesa is far from the favorable conservation state required by the Habitat Directive; the density and state of the trees are unsatisfactory (old age and phytosanitary problems, the “drying”), as well as the conservation state of several species linked to the dehesas (Ferraz-de-Oliveira, Azeda and Pinto-Correia, 2016).

For all this, the management of the dehesa must be focused on the maintenance of an optimal production that can be combined with the conservation of the system at the long term, since most of the traditional rural activities, based on the transmission of success and exclusion of mistakes, have been lost and the active population that keeps the dehesa under use has become old (Law of the Dehesa 7/2010, Green Paper of the Dehesa 2010). In this sense, studies such as the present one may approach, clarify and develop the most adequate sites and techniques, from the economic and ecological perspectives, that ensure the future of the dehesa.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)