Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Convergencia

versión On-line ISSN 2448-5799versión impresa ISSN 1405-1435

Convergencia vol.23 no.71 Toluca may./ago. 2016

Scientific Articles

Defining the others: academic narratives about diversity at School

1University of Seville, Spain. mljimenez@us.es

2University of Salamanca, Spain. r.guzman@usal.es

The present paper reviews Spanish social scientific literature analyzing the employment of the "diversity" concept applied to the school field. The research methodology started with detailed scrutiny and examination of the Social Sciences journals indexed in CSIC-ISOC and DIALNET databases, published between 2006 and 2012, followed by the documentary analysis of 218 articles extracted from those sources. Discourse analysis enables us to single out distinct narrative configurations about how "the other" is defined at school grounds. Results show two hegemonic narrative patterns: an institutional narrative based upon the legal sorting of students classified by scholar results and abilities, and an intercultural narrative constructed around cultural categories that would differentiate nationals from foreigners. We conclude that both accounts unveil predominantly essentialized views of the "diversity" idea and its conceptualization, failing to ponder over other social and economic categories when addressing school related inequalities and differences.

Key words: cultural diversity; literature analysis; social construction of reality; interculturality

Este artículo indaga en los usos académicos del concepto diversidad en el ámbito escolar a partir del análisis de la literatura científica española. El método se basa en el análisis documental partiendo de una exhaustiva búsqueda y revisión de 218 artículos publicados entre 2006 y 2012 en revistas indexadas en CSIC-ISOC y DIALNET. Se aplicó un esquema estructural de análisis que permitió identificar diferentes configuraciones narrativas en torno a la definición del "otro" en la escuela. Los resultados señalan dos relatos hegemónicos: institucional, basado en las clasificaciones legislativas del alumnado en función de sus capacidades y rendimientos escolares; e intercultural, sustentado en categorizaciones en torno a las diferencias culturales derivadas de la condición inmigrante-extranjera. Concluimos que en ambos relatos se proyecta predominantemente una visión esencializada de la diversidad construida desde parámetros dicotómicos y excluyentes, sin apenas considerar otras categorías sociales y económicas en la conformación de las diferencias y desigualdades educativas.

Palabras clave: diversidad cultural; análisis de la literatura; construcción social de la realidad; interculturalidad

Introduction

The matter of diversity has become significantly relevant in education debates, and in pedagogic, politic and academic discourses it has crystalized as an omnipresent and rarely questioned category of thinking, interpretation and order of educational reality. In Spain, this concern for diversity in the classrooms in the last decades has led to a great richness, particularly protected and encouraged by the educational reforms implemented since 1990, and the debates of multiculturalism, studies, programs, and teaching approaches that use this concept as the core of reflection and school intervention for the implementation of student groups identified as different (Coll, 2002; Monsalvo and Carbonero, 2005).

In this sense, the terms diverse and different merge and expand to a network woven with the various kinds of differences that may be identified in school: in skills, learning capacity and ethnic and national origins (Gimeno, 2000). Thus, we find ourselves with a concept that has emerged as a successful study technique [buzzword] in academic and school spheres, but whose senses are neither sufficiently determined nor clarified.

Actually, the word diversity has been labelled as "a soft word", "a euphemism", "a cliché" or a "rhetoric in vogue", which reproaches its automatic use without sufficient theoretical reflection and conceptual precision (IOE Collective, 1997; Duschatzky and Skliar, 2001; Pérez de Lara, 2001; Terrén, 2001; Skliar, 2005). The use of diversity as a descriptive and analytic category of school reality is also characterized by its increasing polysemy when implemented in situations and spheres as varied as those connected with age, gender, religion or sexual orientation (Zapata, 2008-2009 ), which has produced multiple and even contradictory definitions (Almeida et al., 2010; Marvasti and McKinney, 2011; Ramos, 2012).

The use of the concept of diversity, despite it is often depicted as a representation or a reflection of a fact apparently "obvious" or "as natural as life itself " (Gimeno, 2000; Ramos, 2012), it is not neutral, nor socially unbiased. Social constructivism has shown that every concept used to ponder and interpret a certain social reality also contributes to its identification and characterization, pointing out which aspects, subjects or problems require attention and how they are socially depicted and valued (Berger and Luckmman, 2006).

In respect of diversity, these aspects are especially relevant since their use entails classifying and categorizing effects for certain subjects and groups from the typification of certain differences (Duschatzky and Skliar, 2001). Thus, the use of diversity would led to "a process of representation, a symbolic construction of the "other" and hence, a symbolic construction of "us" in which the other is perceived as different or diverse" (Almeida et al., 2010: 333 ).

This "process of differencialism" allots specific subjects to an otherness that gives them a name and makes them the keepers of marks which make them be "different" (Skliar, 2005). The process implies the definition of classificatory mechanisms that, far from being arbitrary, follow a selection and hierarchical organization of certain qualities and characteristics among others, creating an act of exclusion in relation to the norm or the normalized (Almeida et al., 2010).

We need to point out who they are and in what sense they are different. These acts of labeling and delimitation of alterity take place inside asymmetrical and power relationships in which certain agents —positioned in a dominant pole — have and exert power in order to identify, designate and describe other subjects that are often in the dominated pole (Terrén, 2001).

Due to the implications in that categorization and social labeling processes generate in the social structures between groups it is useful to understand and to pay attention to the impact of classificatory mechanisms produced by the hegemonic discourses on diversity. Discourses as social constructions shape reality and become important for the stakeholders of the creation processes and its legitimization. Furthermore, the analysis of narrative configurations (Conde, 2009) can act as analytic structures to detect discursive bias that can be avoided in policymaking and even for inclusive practices of the school stakeholders themselves.

This whole issue and controversy that involves the use of diversity as an analytic category and education policy has led to the approach of this research,1 aimed to analyze on the basis of the examination of Spanish academic literature, the usage of the concept in the research and the intervention in the school sphere, as well as its effects in the discursive processes of construction of the difference.

This study is part of an international tradition of researches and debates on the discursive construction of the diversity category. These studies have been developed mainly in the United States and around race issues and the categorization of school groups in relation to "white" regulation; they have focused on the professors' and college student's discourses (Ahmed, 2007; Berrey, 2011; Marvasti and McKinney, 2011; Bhopal and Rhamie, 2014) as well as the institutional and educational discourse (VanDeventer, 2007).

In the European and Spanish contexts, the available works focus on the professors' discourse (IOE Collective, 1997; Terrén, 2001; Coronel and Gómez Hurtado, 2015; Carrasco, 2015) around cultural differences, described mainly by national origin or specific educational needs (Lawson, Boyask and Waite, 2013).

This research compared to others focused on classroom discourses, represents a different and complementary approach when addressing academic discourses. We center on the discursive production of academic agents due to their central and hegemonic role in the construction and authentication of discoursed on education. In this regard, the academic stakeholders as "knowledge creators" legitimately control the production and articulation of dominant discourses (Van Dijk, 2009: 65-66 ) and the defined "official knowledge" (Berger and Luckmann, 2006: 158 ). Therefore, we look "upward" (Nader, 1972) to the symbolic elites and their role in the establishment of mechanisms to define the differential subjects through the institutionalization of concepts and categories.

As Eduardo Menéndez states (2002: 251) , "the concepts should not be considered an authentic crystallization whose "clarity" should be preserved, since at least in part, they will be unavoidably modified by those who use them in a theoretical, empirical way and/or practically on the basis of their goals, interests and transactions". Thus, instead of just uncover the "authentic" form of the concept, this work describes and analyzes their use in recent academic discourses on diversity in schools, through the evaluation of Spanish scientific literature.

In the same way, we are interested in the social effects of the notion of diversity through the creation and delimitation of barriers between groups, according to what Clifford Geertz (1996: 87) expressed regarding cultural diversity:

The uses of cultural diversity, of its study, description, analysis and comprehension lie less along the lines of sorting ourselves out from others and others from ourselves so as to defend group integrity and sustain group loyalty than along the lines of defining the terrain in which reason must cross if its modest rewards are to be reached and realized. This terrain is uneven, full of sudden faults and dangerous passages where accidents can and do occur, and crossing it or trying to does little or nothing to smooth it out to a level, safe, unbroken plain, but simply make its clefts and contours visible.

From this point of view, this research on academic events regarding diversity at school includes the analysis of the classificatory and defining effects of the differences, as well as the complex, unequal and conflictive relationships around "us" and "the others" that involve the use of diversity as a category.

Method

The methodology used is based on the systematic review and analysis of academic literature published in Spanish scientific journals about the concept of diversity employed in a school context. Among the various products of academic work, the scientific articles were selected as objects of study because of their relevance and meaning in the promotion, exchange and construction of the expert knowledge.

The analytic refinement of indexed scientific production has been carried out with the purpose of examining the hegemonic discourses in the academic field, whose formal criteria of quality are based on the impact of the publications.2 For the creation of the documentary corpus, an exhaustive investigation was made on those articles published in Spanish scientific journals that included in their title or in their key words the term "diversity":

For this purpose, the two main reference and indexing databases of Spanish scientific production were consulted: the contents of Social Sciences and Humanities (ISOC) the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the bibliographic repository DIALNET of the University of La Rioja.

The period of research was from 2006, year of the establishment of the Organic Law of Education (later LOE) which represented a milestone in institutionalization and the establishment of norms for the attention of diversity, to 2012. Along with thematic criteria, other principles for inclusion in the documentary corpus were that they must be research projects, theoretical contributions or analysis/assessment of educational interventions, since they address the Spanish educational situation and that the publication was available in full text.

Finally, a corpus analysis of 218 articles was created. In order to counteract the personal bias of material selection, the investigation was done at several stages of the research and by different members of the team.

The texts were analyzed following a structural outline with the purpose of identifying the meaning of the articles by defining its writing's consistencies (Alonso and Fernández, 2006). To that end, four dimensions of analysis may be identified (see Table 1 3 ). The first examines the arguments used to justify the need, relevance and suitability of attention to diversity in the school setting. The second one refers to the meanings and uses of this notion relation to the classificatory implications and differentiation between groups and categorization of the subjects that were "different". The third involves the assessment on the development of diversity and the subjective attributions reflected in academic discourses.

These assessments entail and authenticate certain answers to requests coming from texts to educational and political institutions providing pedagogic solutions in order to achieve some educational and political goals. These last two aspects assimilate the fourth dimension of analysis. Regarding these dimensions, the articles, on one hand, were measured quantitatively from their formal features, authorship profiles and definitions of diversity; while on the other, the discourse on motivations and arguments to address diversity in schools was analyzed qualitatively.

This allowed identifying definitions, meanings and assessments around the concept, as well as the characteristics used to differentiate them along with the answers to questions raised by diversity. The software Atlas.ti7 was used to organize the texts and codify their content. The codification process, as well as the material selection was coordinated and contrasted with different members of the research team. This structure of analysis was used to identify different narrative configurations (Conde, 2009: 168-169 ) that could occur around diversity based on the exploration and polarization of tensions, conflicts and different stances in the discourses toward the selected analysis dimensions.

Conde (2009: 168) defines narrative configurations as an "analytical operation consisting of choosing and selecting those text dimensions which by literally informing about it (...) allow at the same time polarizing it and bringing it together with the social context in which it was produced, just as with the research objectives". Narrative configurations, at the same time have allowed identifying the symbolic strength of discourses from a sociological analysis in addition to provide an analysis and reflection framework on how the context expresses in text (Conde, 2009: 206).

Moreover, the consideration of narrative configurations allows organizing the totality of discourses on diversity, as well as the internal analysis of the texts around the concept in Spanish schools.

Results

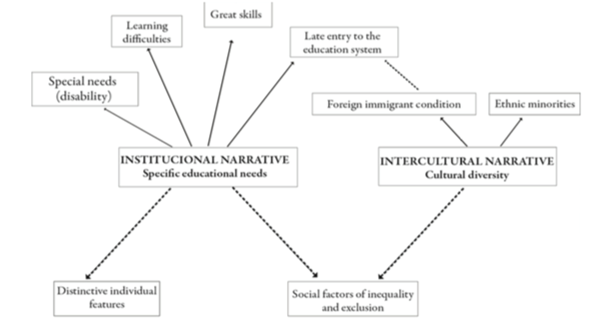

The analysis of more than two hundred articles unveils the coexistence of two hegemonic narrative patterns, although however they show variations or drifts in their perception of diversity (see Figure 1). The institutional discourse stands out, based on the definitions and classification of the student body a priori specified by the Spanish education legislation according to abilities, experience and school performance.

The other main discourse is the intercultural one. This focuses on the cultural dimension of diversity, which is generally understood in relation to the foreign immigrant condition. These dominant narratives account for most (50.5%: the institutional discourse; and 40.4%: the cultural one) of the analyzed articles. The analysis of discourse configurations has unveiled two narratives as different and distant lines of discourse in respect of the assessed analytic dimensions summarized in Table 2.

This analysis includes elements of the Weberian ideal type construction; this way, in order to define these narratives, the specific and essential features that differentiate them from one another on the basis of the analysis of specific, individual texts are considered. Thus, it is possible that different visions of diversity coexist in the same text, even if it has been codified according to the vision considered predominant.

Nevertheless, both narratives, as we shall see, also share discursive elements of a pedagogical-functionalist logic (Martín Criado, 2010) on which most of the analyzed texts are based.4 It is also worth noticing the presence of other minority and secondary perceptions of diversity that focus on the social manifestations of inequality in education and on the consideration of other expressions of diversity within a familial, sexual and regional context.

Finally, regarding the kind of academic publications that form the different discourses, even if most of them have a researching nature (48.7% in the case of intercultural discourse and 47.3% in the institutional ones), the institutional discourse includes more publications that deal with pedagogic experiences (18.2% vs. 6.8% of the cultural one).

The intercultural discourse comprises a much larger group of theoretical works (44.3% vs. 34.5% of the institutional). Furthermore, it is worth to highlight the preeminence of the use of quantitative techniques in institutional discourse works (39% vs. 23% of the intercultural) and of qualitative in cultural ones (61% vs. 37% of the articles of the institutional discourse).

The institutional discourse: diversity as a deficit and the specific educational needs as makers of the difference

The institutional discourse, as mentioned earlier, is basically supported on the definition of diversity according to the Spanish education regulations, specifically based on two legislative milestones: the Organic Law of the General Organization of the Education System (LOGSE) in 1990 and LOE in 2006. In fact, the main reasons to address diversity are mainly based on the enforcement of the legislation in the educational practices that "have been shaping a set of resources and pedagogical answers that have endeavored to look after a more heterogeneous student body in relation to abilities, sociocultural and geographic background, motivation for studying and family expectations for the future" (Sales et al., 2010: 2 ).

Even though LOE, throughout its development alludes to different situations —"diversity of interests, characteristics and personal situations", "affectivesexual diversity", "cultural and linguistic diversity in the different Autonomous Communities", "learning difficulties", "unfavorable socioeconomic conditions", "late entry to the education system", "special needs"... —, "attention to" basically refers to those students "with specific needs of educational support".

Its Title II on "Equity in Education" stipulates what these needs are based on the student body's requirements of "special educational needs, specific learning difficulties, high intellectual capacity, late entry to the education system or due to personal conditions or past school records", to ensure that all of them "reach the maximum, possible development of their personal potential, as well as the objectives of general nature for all the students" (LOE, art. 71.2, 2006).

The works registered within the institutional narrative replicate the distinction and classification criteria of the student body established by LOE. Most of them (around 64%) address specific education needs regarding the learning deficits and problems of the students in respect of standard criteria.

Another key element of the educational diversity research refers to possible situations of students' impairment (around 23%). This is categorized as "the students with special education needs" in reference to: "subjects that, due to different circumstances —psychological, physical or emotional —, are not able to completely adapt to a normal education.

Throughout the educational process an effort is made so that the subjects can reach human formation and the preparation needed to personally, socially and professionally integrate into the society they belong to" (Araque and Barrio, 2010: 5 ). In the case of specific as well as special needs, the distinction of the individuals is demarcated and subject to professional evaluation and diagnosis that will determine the protocols to foster the adaptation and curricular diversification of special education (Araque and Barrio, 2010; Castaño, 2011; Toro, 2011).

With regard to the limitations in terms of the students' abilities, the excess of them —situation entitled in different ways such as: "intellectual giftedness", "successful intelligence", "great skills" — is based on other mechanism of educational differentiation. However, a significantly reduced number of researches addresses this aspect (around 5%), many of them from the perspective of psychology. Despite these children are distinguished by their exceptional nature, paradoxically they end up being burdened with problems, not because of their superior performance, but because of "their learning, school and social integration issues" reflected in a high percentage of "poor performance" and "academic failure" of "gifted" students. This imbalance could be explained by the lack of detection, diagnosis and evaluation (Comes et al., 2009).

Additionally, concerning "late entry to the Spanish education system" —in reference to foreign immigrant students5 — the number of articles that address it is limited (around 3%), becoming an issue that begins with the early assignment of accumulated curricular deficits due to the "lack of awareness of the medium of instruction in the teaching and learning process, the significant school discrepancy and the integration of the student body" (García García et al., 2012: 260 ).

The structure of foreign students' difference in education is accompanied by distorted views that contribute to spread ethnic prejudices.66 Finally, it is evident that a minority of articles (5%) within this institutional narrative address other aspects of difference, essentially linked to family (regarding the plurality of family forms) and geographical diversity (regarding the distinctive educational and regional or rural features).

Despite the heterogeneity of situations of the different students' categories, these are structured and basically work around the idea of deficit and dichotomy of normality vs. non-normality. The use of diversity is strongly connected to the ideology of normality (Pérez de Lara, 2001), which qualifies certain order in which "not only the idea of classification of the normal differentiating it from the abnormal is stressed, but also practices and knowledge —disciplines, institutions, professions — in charge of normalizing the vast group of individuals who do not meet the desired characteristics are structured" (Almeida et al., 2010: 30 ).

Those students labeled as special or with specific needs from the implementation of certain protocols become a focus of attention of specialized professional assistance. This process easily ends in the classification77 of those who do not follow the "ordinary" levels.

In these prevailing configurations, we identify two derivations or discourse drifts in function of their focus on the individual distinctive features or on the socioeconomic conditions that affect the students' uneven academic performance.

Regarding the first drift, a significant trend is noticeable within institutional narratives to prompt educational divergence from "individual differences". "These texts support the suitability of coming up with the "diversity of all the students", "not only of those identified with a specific need of educational support in order to achieve effectively inclusive education (Vigo et al., 2010: 149 ).

This way, "attention to diversity" should understand that all the students are "special", identifying those "differences that make humans unique (Méndez and Del Pino, 2006). In short,

Each student is different, so education must treat individual differences (...), therefore, attention to diversity consists of implementing a model of education capable of offering each student the required academic support, adapting educational intervention to the individuality of the student body: this aspiration is no other than to adapt education to the different students' abilities, interests and motivations (Araque and Barrio, 2010: 11 ).

These distinctive features, often sparsely identified, frequently allude to differences in motivation and "learning styles" (Arnaiz, 2008; Navarro, 2011). This way of defining education difference can lead to a psychologization, even a biologization of academic performance in terms of the individuals' abilities and talents, what may constitute a dangerous split toward individualist, meritocratic ideas that refuse to acknowledge the influence of the social environment.

Moreover, another drift can be seen in certain texts, in which the interpretation of differences in education imply deeper social understanding. This focuses on social and economic factors that generate not only differences but also inequities between social groups. Particularly between the students' academic records and performance. These are often qualitative theoretical studies that focus their attention on the influence of disadvantaged social environments and policies on attention to diversity.

Therefore, "the hidden face of diversity in schools" stands out: the academic failure that the "more different and vulnerable" people endure in educational systems (Martínez, 2011: 167) and segregation problems, inequality and social and educational exclusion (Ballester and Vecina, 2011). They also bring up the effects of the labeling and stigmatization generated by academic diversification programs. (Vega and Aramendi, 2009). Academic failure within this context is defined in social rather than personal terms; hence, they demand overcoming individualist interpretations to incorporate broader and comprehensive perspective of the problem in education.

In this institutional perspective, the expected answers proposed to institutes and political stakeholders rely upon "addressing" and "treating" those who show some kind of difficulty or educational need. According to the analyzed texts, these measures are focused on the improvement of the quality and effectiveness of education, which should become an improvement of the academic performance and graduation of the students that show some sort of academic disadvantage.

For this reason, pedagogical innovations and interventions take on special importance in the classroom, especially those linked to natural and experimental science subjects that enhance the students' skills and abilities. Along with the quest for improvements in academic performance, the publications also include constant references to inclusive education as a formula to boost educational effectiveness in the centers' measures regarding students' diversity. (Barrio, 2009; García García et al., 2012).

In this sense, the attention to diversity can facilitate the development of a "unique, egalitarian and quality education [...] that rejects any kind of academic exclusion and boosts participation and equitable learning" (Araque and Barrio, 2010: 4 ).

Intercultural narrative: foreign immigration and cultural differences as a source of diversity

The intercultural narrative of diversity identified in the analysis of Spanish documentary sources, is based on the need of addressing the immigration phenomenon in schools, and in particular the "strong", "gradual increase", "massive" arrival of foreign students to the classrooms (García Medina, 2006; Herrada, 2009; García Fernández et al., 2010), in these justifications common subjects around the structure of nondomestic immigration in Spain as an issue have been discussed (Santamaría, 2002; Gijón et al., 2006).

This way, immigration, or at least certain immigration and certain immigrant groups become the main leitmotiv to advocate for an educational change:

In the last decades, our home country has changed from being a country of emigrants to a country that receives immigrants from different places, ethnic groups, customs, languages and religions. Likewise, focusing on an educational context, the existence of multicultural classrooms and the multicultural phenomenon seen as the plurality of students from different background in common educational grounds is evident (Leiva, 2011: 5 ).

Nonetheless, it is still paradoxical that this discovery of the multicultural phenomenon has been done without taking into account other cultural differences that have defined Spanish classrooms. In fact, only a 6% of the articles in this narrative addresses gypsy population as a characteristic cultural agent, however this is the ethnic minority with the greatest and most ancient presence in Spain and which faces serious problems of marginalization and exclusion.

Virtually, all the publications focus on foreign immigration, however to a limited and partial extent when addressing certain nationalities or backgrounds related to "developing countries" or non-EU countries. The associated immigration and multiculturalism demand the education community new adaption strategies and the inclusion of these new culturally different individuals (García Velasco, 2009).

Within this discourse, cultural difference focuses primarily on the advisability of national or foreign geographic backgrounds. Culture is diminished to the "mark" of one's or the family nationality, coming to specific, more clear and concrete variables such as language, religion or particular physical features.

The categories "immigrant" and or "foreign" are stablished as key indicators of the configuration of cultural differences, often assumed in a deterministic, standstill, static way as a weight that cannot be taken over even after having acquired the nationality for example, or after having been born in Spain (the denomination "second generation" is an example of this permanent mark).

This view of diversity and cultural otherness contrasts with the one of diversity discourses generated in other contexts, as in Latin America, where the central aspects are more based on rural and indigenous conditions (Ibáñez et al., 2012) or in the United States, focused on racial difference (Ahmed, 2007; Berrey, 2011; Marvasti and McKinney, 2011; Bhopal and Rhamie, 2014).

The definition of diversity from this intercultural discourse reflects, all in all, an essentialized and homogenizing view of culture, which affects both the "autochthonous" and the one attributed to other individuals or foreign groups. The "myth of cultural domestic consistence" is recreated, in which cultures are communities with homogenous beliefs and lifestyles, so that "cultural diversity becomes an ontological category: it assumes the assimilation of pre-established cultural contents and customs free from mixtures and contamination" (Duschatzky and Skliar, 2001: 197 ).

This difference between cultures is essentially addressed as something negative and excluding: "non-domestic", "non-autochthonous", and ultimately "strange", "not like us", ignoring in most of the cases cultural differences and inequities within the immigrant foreign group, either by background, age, gender or social status. The texts are in fact often uncertain about the geographic origins of the students who they claim to assist in the matter of diversity.

There are few publications in which concrete origins are pointed out or specified, even when most of them meet the statistic criteria of classification of administrative agencies or comprehensive geographic classifications, for example, according to continent or "cultural area". Nevertheless, in the publications that take into account the concrete origins of the students, there is a type of culturally diverse learner that attracts special attention, and that is the "Latin American students", a category that operates as a big container and unifier of cultural differences, and that is not absolved of stereotypical interpretations and that simplify these "other cultures", "identity cultures" and their education systems.

Thus, in many analyzed texts it can be observed, as Gunther Dietz (2008: 20) states, "a tendency to implicitly "make problematic" the existence of cultural diversity in the classroom "being of interest" without critical sense, basic Anthropology concepts such as "culture", "ethnic group" and "ethnicity" in their often obsolete, nineteenth-century definitions", which leads to an ethnification of the cultural differences through a dehumanization of the bearers.

These processes of categorization of the other, as Eduardo Menéndez (2002: 109) points out, imply "ignoring the individual, or considering indistinguishable from the local group the ethnicity, the community of origin in such a way that the individual acquires/expresses the characteristics of these considered homogeneous, integrated, coherent, authentic, etc. units and which, at the same time, are typical of the culture and the subject".

Using the diversity from the "us"/"them" dichotomy has homogenizing, globalizing effects since it masks the heterogeneous nature of "immigrant" groups, not only their nationality or geographic background, but also the cultural differences between regions or groups for example, and some other structural factors and conditions that operate with nationality/race/ethnic group at the same time8 such as gender, social status, age, sexual orientation or psychomotor skills.

Just a few of the analyzed texts written from a qualitative, theoretical, reflexive perspective, present a critical approach to the simple explanation of academic difference in terms of "mere inherent, community attributes", defending at the same time the social historical context and structural inequalities (Franzé, 2008).

They criticize the assimilation, discriminatory, segregation effects of a part of the student body, extracted from an exclusively pluralist interpretation of the difference: "diversity is not only a social reality that can be addressed from a situation of opinions and marginalized identities; but from a general approach accountable for the way processes of subjectivization occur as articulatory exercises affected by unequal and hierarchic power relations" (Madero et al., 2011: 146 ).

They warn about the "contradiction that entails addressing a diversity in which everybody fits, and at the same time, suggest addressing the diversity" in which the diverse ones are the others, the different ones, the displaced of the "normal", "[...], the foreign, the odd that do not follow the common standard of most people, the "one that must be'" (Sánchez, 2011: 145).

As for the institutional view that values diversity in terms of scarcity and problems for teaching, the cultural view is accompanied by a highly optimistic perception of diversity as a "challenge", a "positive value" and "richness" (Martín Rojo, 2007; Leiva, 2011). The inclusion of cultural differences to the educational process is then, a beneficial opportunity (Herrada, 2009).

These disparate assessments can be clearly observed in the case of the foreign immigrant students' language. Unlike the institutional approach that assess the linguistic difference in terms of curricular deficit regarding the lack of knowledge of the "autochthonous" language, the intercultural approach values the knowledge of other languages in terms of cultural competencies "especially the linguistic resources that define these children and young people. They constitute a valuable individual and collective capital in a world increasingly globalized" (García-Cano et al., 2010: 292 ).

The distances between these two discourses can be observed when conceiving diversity in the articles in the latter approach, in the answers given about the "challenges" stated by "immigrant students" and foreign multiculturalism. These are based on intercultural education tools, where pacific coexistence, recognition and respect for cultural differences are the central goals.

With this intentions, transversal projects and planning are common. They expect to improve the "culturally different" students' relations and interactions. Humanistic subjects that spread values play an important role. Thus interculturality could be defined as "true and effective interaction between cultures that can allow learning and acknowledging one another by means of previous understanding based on respect.

The other is not a contaminant, but an enrichment that undoubtedly should be encouraged in all social spheres and among them, education; "attention to diversity" in a way that includes each and every aspect in the classroom as much as outside it (Sánchez, 2011: 151). Above all, the key of change is not only in encouraging individual skills as an institutional approach, but "promoting interactions among individuals with different social and cultural systems that coexist in the same context" (Ayora, 2010: 45 ).

Interculturality is assumed as the ideal channel for cultural differences to flow to the education system that, on the other side, has the intrinsic responsibility to generate an atmosphere of coexistence and egalitarian learning, thereby caring and inclusive, in some texts described as "emancipator" (Hernández de la Torre, 2009; Leiva, 2011). Facing a cultural issue, the unavoidable answer is of the same nature, which leads to a re-interpretation of socio-economic, legal and or political inequities as cultural differences (Dietz, 2012).

Nevertheless, together with the institutional approach, this should be the initial, appropriate and permanent teacher training, upon which the main solutions for diversity "challenges" fall. School is intended to be an autonomous, self-sufficient, and introspective system with the teacher as the main actor, an "essential element" of education and social changes, since they manage the socialization processes that guarantee social and cultural cohesion.

In both discourses, an answer based on curricular transformation and teacher training improvement is demanded: mainly in terms of attitudes and sensibility for culture. Each approach would manage central elements of the "regular pedagogic discourse" —didactic pre-eminence, persistence of resources and the focus on in-school processes — (Villar and Hernández, 2013) and of idealist premises that support the majority of school reforms (Martín Criado, 2004).

Conclusions

The analysis of Spanish scientific publications on diversity in the education sphere, has allowed to divide, from the identification of the discourse configurations, two hegemonic narratives. On one hand, an institutional discourse based on the normative definition of educational diversity according to various skills and academic performance. On the other, there is an intercultural discourse in the classrooms.

Even if both narratives select different characteristics for classification and hierarchical organization, common mechanisms of construction of the difference are observed. First, these are aimed for students who have personal or cultural characteristics that define them as diverse. Second, these characteristics are defined and assigned by a dichotomist reproduction process of inclusion and exclusion lines with reference to what is identified as normal, either in terms of academic performance or geographic-cultural identification.

Paradoxically, in this way diversity ends up remaining in terms of "opposition to totalities of normality", contributing to "guarantee fixed, centered, homogeneous, steady identities" (Duschatzky and Skliar, 2001: 189 ).

The construction of the difference from certain education and cultural parameters in a dichotomist and excluding way also has disguising effects for situations of inequality, segregation and disadvantage emphasizing certain features that define and make a community diverse (Duschatzky and Skliar, 2001; Ramos, 2012). In this way, in the majority of the works in these two approaches, omission and undervaluing of social and economic contexts in the determination of the differences and inequities in the school sphere are present.

In the institutional, notably, the individual differences are emphasized in terms of heterogeneity of skills, performance and academic records, even arriving to certain biologicist interpretation of the difference in education. In the cultural, however, the individuals' distinctive features vanish due to an essentialists and homogenizing designation in certain characteristics of the cultural group they belong to according to their foreign immigrant condition.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting the necessity in both configurations of minor drifts to critical positions that question the essentialist nature of the prevailing discourse on diversity in school. These works —many of them developed from qualitative methodologies and theoretical perspectives susceptible to inequality — that highlight the importance of the socio-economic matter and the need to study the interactions of the education and cultural differences with other factors of difference and inequality such as social status, gender, ethnicity or territory.

These results cannot be understood without addressing the context of text production —essentially inside the pedagogic discipline tradition — and the kind of academic product to analyze —indexed articles according to thematic and methodologic standards with which the academic field operate. This is why, a future line of research could focus on the study of the appearance of new critical discourse positions toward diversity.

In any case and despite the intentions stated in some publications, the improvement of the model for binary categories, as well as the consideration of other conceptual instruments to put diversity in a context that supports intersections has not consolidated yet (Guzmán-Ordaz and Márquez-Lepe, 2012). This is an important matter since depending on how the labels that designate "the different" as well as the distances that separate us from them, are academically and socially defined and authenticated, the mechanisms of relation and social transaction between groups would be defined and authenticated as well (Menéndez, 2002).

This is therefore embodied in the correlation between diversity discourses and the policies of difference's recognition of minorities that portray the idea that a society must include, accept and respect the differences of everyone that constitute it (Almeida et al., 2010).

The danger of relativism is present like a shadow in the discourses about diversity that accept the different as a principle (Duschatzky and Skliar, 2001). There are also paradoxes that entail the policies of difference to make up for particularism in a socio-economic framework increasingly fragmented and selective (Alonso, 2005).

In short, the discussion around the use of diversity and the debates that it entails, cannot be restricted to the processes of construction, recognition or celebration of the difference, but also, above all, to social implications regarding those "fissures" and "contours" —as Geertz mentions — that trace our relationship with the others and the dynamics of social integration in an unequal world.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara (2007), "The language of diversity", en Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 30, núm. 2, UK: University of Surrey. [ Links ]

Almeida, María Eugenia et al. (2010), "Nuevas retóricas para viejas prácticas. Repensando la idea de diversidad y su uso en la comprensión y abordaje de la discapacidad", en Política y Sociedad, vol. 47, núm. 1, España: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. [ Links ]

Alonso, Luis Enrique (2005), "¿Redistribución o reconocimiento? Un debate sociológicamente no siempre bien planteado", en Ariño, Antonio [ed.] Las encrucijadas de la diversidad cultural, España: CIS. [ Links ]

Alonso, Luis Enrique y Carlos J. Fernández (2006), "Roland Barthes y el análisis del discurso", en Empiria. Revista de Metodología de las Ciencias Sociales, núm. 12, España: UNED. [ Links ]

Araque, Natividad y José Luis Barrio (2010), "Atención a la diversidad y desarrollo de procesos educativos inclusivos", en Prisma Social. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, núm. 4, España: Fundación iS+ D para la Investigación Social Avanzada. [ Links ]

Arnaiz, Pilar (2008), "Indicadores de calidad para la atención a la diversidad del alumnado en la educación secundaria obligatoria", en Revista de Educación, núm. 349, España: Ministerio de Educación Cultura y Deporte. [ Links ]

Ayora, María del Carmen (2010), "Diversidad lingüística y cultural en un ámbito educativo de lenguas de contacto", en Pragmalingüistica, núm. 18, España: Universidad de Cádiz. [ Links ]

Ballester, Lluís y Carlos Vecina (2011), "Intervención comunitaria, diversidad y complejidad social. El problema de la segregación social en la escuela", en Prisma Social. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, núm. 6, España: Fundación iS+ D para la Investigación Social Avanzada. [ Links ]

Barrio, José Luis (2009), "Hacia una educación inclusiva para todos", en Revista Complutense de Educación, vol. 20, núm. 1, España: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. [ Links ]

Berger, Peter y Thomas Luckmann (2006), La construcción social de la realidad, España: Amorrortu. [ Links ]

Berrey, Ellen C. (2011), "Why diversity became orthodox in higher education, and how it changed the meaning of race on campus", en Critical Sociology, vol. 37, núm. 5, UK: Association for Critical Sociology. [ Links ]

Bhopal, Kalwant y Rhamie, Jasmine (2014), "Initial teacher training: understanding 'race', diversity and inclusion", en Race Ethnicity and Education, vol. 17, núm. 3, UK: University of Birminghan. [ Links ]

Carrasco, Concepción (2015), "Discurso de futuros docentes acerca de la diversidad intercultural", en Papers, vol. 100, núm. 2, España: Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. [ Links ]

Castaño, Raimundo (2011), "El currículum y a la atención a la diversidad en las etapas de Educación Básica, Primaria y Secundaria Obligatoria, en el marco de la Ley Orgánica de Educación", en Hekademos. Revista Educativa Digital, núm. 6, España: Asociación AFOE. [ Links ]

Colectivo IOE (1997), La diversidad cultural y la escuela. Discurso sobre atención a la diversidad con referencia especial a las minorías étnicas de origen extranjero, España: CIDE. [ Links ]

Coll, César (2002), "La atención a la diversidad en el proyecto de Ley de Calidad de la Educación o la consagración del orden natural de las cosas", en Aula de Innovación Educativa, núm. 115, España: Grao Publicaciones. [ Links ]

Comes, Gabriel et al. (2009), "Análisis de la legislación española sobre la educación del alumnado con altas capacidades", en Escuela Abierta, núm. 12, España: Fundación San Pablo Andalucía. [ Links ]

Conde, Fernando (2009), Análisis sociológico del sistema de discursos, España: Colección Cuadernos metodológicos, núm. 43, Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. [ Links ]

Coronel M José. e Inmaculada Gómez-Hurtado (2015), "Nothing to do with me! Teachers' perceptions on cultural diversity in Spanish secondary schools", en Teachers and Teaching, vol. 21, núm. 4, UK: International Study Association on Teachers and Teaching. [ Links ]

Dietz, Gunther (2008), "El paradigma de la diversidad cultural: tesis para el debate educativo", en IX Congreso Nacional de Investigación Educativa. Conferencias Magistrales: México. [ Links ]

Dietz, Gunther (2012), Multiculturalismo, interculturalidad y educación: una aproximación antropológica, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Duschatzky, Silvia y Carlos Skliar (2001), "En nombre de los otros. Narrando a los otros en la cultura y en la educación", en Larrosa, Jorge y Carlos Skliar [eds.] Habitantes de Babel: Políticas y poéticas de la diferencia, España: Laertes. [ Links ]

Franzé, Adela (2008), "Diversidad cultural en la escuela. Algunas contribuciones antropológicas", en Revista de Educación, núm. 345, España: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. [ Links ]

García Cano, María et al. (2010), "Estrategias bilingües e interculturales en familias transmigrantes", en Revista de Educación, núm. 352, España: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. [ Links ]

García Fernández, José Antonio et al. (2010), "Estudio del sistema y funcionamiento de las aulas de enlace de la Comunidad de Madrid. De la normativa institucional a la realidad cotidiana", en Revista de Educación, núm. 352, España: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. [ Links ]

García García, Mercedes et al. (2012), "Medidas eficaces en atención a la diversidad cultural desde una perspectiva inclusiva", en Revista de Educación, núm. 358, España: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. [ Links ]

García Medina, Raúl (2006), "Un enfoque educativo piagetiano desde la práctica docente: en tomo a la adquisición del concepto de número por alumnos con discapacidad cognitiva", en Tendencias Pedagógicas, núm. 11, España: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. [ Links ]

García Velasco, Alba (2009), "La integración del alumnado inmigrante en el ámbito escolar: adecuar los recursos y aprovechar la diversidad", en Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, vol. 22, España: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. [ Links ]

Geertz, Clifford (1996), Los usos de la diversidad, España: Paidós. [ Links ]

Gimeno, José (2000), "La construcción del discurso acerca de la diversidad y sus prácticas", en Aula de Innovación Educativa, núm. 81-82, España: Grao Publicaciones. [ Links ]

Gijón Sánchez, M. Teresa et al. (2006), "Más allá de la diferencia, tras el cristal de la diversidad. La inmigración en la literatura biomédica en España", en Fernández Juárez, Gerardo [coord.] Salud e interculturalidad en América Latina. Antropología de la salud y crítica intercultural, Ecuador-España: Abba-Yala. [ Links ]

Guzmán-Ordaz, Raquel (2015), "El paradigma interseccional: rutas teóricas-metodológicas para el análisis de las desigualdades sociales", en Saletti-Cuesta, Lorena [coord.] Traslaciones en los estudios feministas, Málaga: Perséfone-Universidad de Málaga. [ Links ]

Guzmán-Ordaz, Raquel y Esther Márquez-Lepe (2012), "Intersectionality as a Research Strategy for Diversity in Education 'field' and Migration Process", en IAIE International Conference: Tapelewilis for Intercultural Education: Sharing Experiences, building alternatives: Veracruz, México. [ Links ]

Hernández de la Torre, Elena (2009), "Una educación entre culturas en el punto de mira de la atención a la diversidad", en Revista de Educación Inclusiva, vol. 2, núm. 2, España: Universidad de Jaén. [ Links ]

Herrada, Rosario (2009), "Mosaicos conceptuales vinculados a la diversidad cultural de estudiantes universitarios de magisterio: más que palabras", en Docencia e Investigación, año 34, núm. 19, España: Universidad de Castilla La Mancha. [ Links ]

Ibáñez Salgado, Nolfa et al. (2012), "La comprensión de la diversidad en interculturalidad y educación", en Convergencia: Revista de Ciencias Sociales, núm. 59, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. [ Links ]

Jiménez-Rodrigo, María Luisa et al. (2009), "El análisis de la literatura biomédica en España en clave de diversidad cultural y de género", en Empiria, núm. 17, España: UNED. [ Links ]

Jiménez-Rodrigo, María Luisa y Raquel Guzmán-Ordaz (2013), "Sociología de la construcción de los conceptos académicos: el caso de la 'diversidad' en educación", en Sociología Histórica, núm. 2, España: Universidad de Murcia. [ Links ]

Lawson, Hazel, Boyask, Ruth y Sue Waite (2013), "Construction of difference and diversity within policy and practice in England", en Cambridge Journal of Education, vol. 43, núm. 1, UK: University of Cambridge. [ Links ]

Leiva, Juan José (2011), "Fundamentos Pedagógicos de la Educación Intercultural: construyendo una cultura de la diversidad para una escuela humana e inclusiva", en Miscelánea Comillas, vol. 69, núm. 134, España: Universidad Pontificia de Comillas. [ Links ]

LOE. Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación (2006), España: Gobierno de España. [ Links ]

Madero, Beatriz et al. (2011), "Repensando la diversidad en la escuela", en Revista de Estudios de Juventud, vol. 11, núm. 95, España: INJUVE. [ Links ]

Martín Criado, Enrique (2004), "El idealismo como programa y como método de las reformas escolares", en El nudo en la red, núm. 3-4, España: Coordinadora de Asociaciones Culturales de Madrid. [ Links ]

Martín Criado, Enrique (2010), La escuela sin funciones. Crítica de la sociología de la educación crítica, España: Bellaterra. [ Links ]

Martín Rojo, Luisa (2007), "'Sólo en español': una reflexión sobre la norma monolingüe y la realidad multilingüe en los centros escolares", en Revista de Educación, núm. 343, España: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. [ Links ]

Martínez Domínguez, Begoña (2011), "Luces y sombras de las medidas de atención a la diversidad en el camino de la inclusión educativa", en Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, vol. 25, núm. 1, España: AUFOP. [ Links ]

Marvasti, Amyr y Mckinney, Karyn (2011), "Does diversity mean assimilation?", en Critical Sociology, vol. 37, núm. 5, UK: Association for Critical Sociology. [ Links ]

Méndez, María Félix e Inmaculada del Pino (2006), "La atención a la diversidad en educación física. Propuestas de actuación docente", en Efsdeportes.com, Revista Digital, año 11, núm. 97, España: Universidad de Barcelona. [ Links ]

Menéndez, Eduardo (2002), La parte negada de la cultura. Relativismo, diferencias y racismo, España: Bellaterra. [ Links ]

Monsalvo, Eugenio y Miguel Ángel Carbonero (2005), "La atención a la diversidad como ideología educativa", en Revista Psicodidáctica, vol. 10, núm. 1, España: Universidad del País Vasco. [ Links ]

Nader, Laura (1972), "Up the anthropologist. Perspectives gained from studying up", en Dell Hymes [coord.] Reinventing Anthropology, New York: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

Navarro, Manuel (2011), "Medidas educativas y organizativas de atención a la diversidad que mejoran el rendimiento escolar en el IES Sierra de los Filabres de Serón (Almería)", en Espiral. Cuadernos del profesorado, vol. 4, núm. 7, España: Centro de Profesorado de Cuevas Olula. [ Links ]

Pérez de Lara, Nuria (2001), "Identidad, diferencia y diversidad: mantener viva la pregunta", en Jorge Larrosa y Carlos Skliar [eds.] Habitantes de Babel: Políticas y poéticas de la diferencia, España: Laertes. [ Links ]

Ramos, José Antonio (2012), "Cuando se habla de diversidad ¿de qué se habla? Respuestas desde el sistema educativo", en Revista Interamericana de Educación de Adultos, año 34, núm. 1, México: OEA. [ Links ]

Sales, Auxiliadora, Odet Moliner y Lidón Moliner (2010), "Estudios de la eficacia académica de las medidas específicas de Atención a la Diversidad desde la percepción de los implicados", en Estudios sobre Educación, núm. 19, España: Universidad de Navarra. [ Links ]

Sánchez Rojo, Alberto (2011), "Raimón Panikkar va a la escuela: diálogo intercultural y atención a la diversidad", en Bajo Palabra. Revista de Filosofía, II época, núm. 6, España: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. [ Links ]

Santamaría, Enrique (2002), La incógnita del extraño. Una aproximación a la significación sociológica de la "inmigración no comunitaria", España: Anthropos. [ Links ]

Skliar, Carlos (2005), "Poner en tela de juicio la normalidad, no la anormalidad. Políticas y falta de políticas en relación con las diferencias en educación", en Revista Educación y Pedagogía, vol. 17, núm. 41, Colombia: Universidad de Antioquia. [ Links ]

Terrén, Eduardo (2001), "La conciencia de la diferencia étnica: identidad y distancia cultural en el discurso del profesorado", en Papers, núm. 63/64, España: Universidad de Barcelona. [ Links ]

Toro, Laia (2011), "Uso de perfiles de personalidad para la atención a la diversidad: evidencias en alumnos de educación especial", en Educación y diversidad. Revista Interamericana de Investigación sobre Discapacidad e Interculturalidad, vol. 4, núm. 1, España: Universidad de Zaragoza. [ Links ]

Van Deventer Iverson, Susan (2007), "Camouflaging power and privilege: A critical race analysis of university diversity policies", en Educational Administration Quarterly, vol. 43, núm. 5, USA: University Council for Educational Administration. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, Teun A. (2009), Discurso y Poder, España: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Vega, Amando y Pello Aramendi (2009), "La atención a la diversidad: interrogantes para la iniciación profesional de los 'fracasados'", en Enseñanza and Teaching, núm. 27, España: Universidad de Salamanca. [ Links ]

Vigo, Begoña et al. (2010), "Preparando profesores para la atención a la diversidad: potencialidades y limitaciones de un proyecto de innovación y mejora interdisciplinar", en Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación de Profesorado, vol. 24, núm. 3, España: Universidad de Zaragoza. [ Links ]

Villar, Alicia y Francesc Jesús Hernández (2013), "Anomalías sociológicas en el discurso pedagógico", en Praxis Sociológica, núm. 17, España: Universidad de Castilla La Mancha. [ Links ]

Zapata, Ricard (2008-2009), "Diversidad y política pública", en Nuria del Viso [coord.] Dossier Reflexiones sobre las diversida(des), España: Centro de Investigación para la Paz (CIP-Ecosocial). [ Links ]

1 Work carried out within the I+D+i project "Escuela, comunidad e interculturalidad: estudio de los procesos interculturales e inter-actorales ante la gestión de la diversidad cultural en los centros educativos" (EDU2010-15808), financed by The Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and the excellence project of the Regional Government of Andalusia "Estrategias innovadoras en Educación Intercultural: estudio de las distintas gramáticas de la gestión de la diversidad en los centros educativos" (SEJ-6329).

2An earlier work ( Jiménez-Rodrigo and Guzmán-Ordaz, 2013) analyzes the implications of the rules of the game on the academic discourses around diversity that determine authentication possibilities in the different discourse configurations.

3Tables 1 and 2 and the Figure can be found in the Annex at the end of the document (Editor's note).

4The characteristics of spaces and stakeholders that make use of discourses of diversity, as well as their production contexts have been addressed in another work ( Jiménez-Rodrigo and Guzmán-Ordaz, 2013). Most of these texts are part of the disciplinary tradition of the Educational Sciences.

5 The difficulties in the kind of student body that is specified in the law, relate to "weak language skills, competencies or basic knowledge", that may complicate education, but also concerning the families about the need of "relevant advice concerning the rights, obligations and opportunities which incorporation into the Spanish education system implies" (LOE, art. 78, 2006).

6For example, that these children have not been educated in "their country of origin", "they live on the streets" or "they are exploited in workshops"; and other prejudices about their lack of motivation to education or their families and coexistence issues. In this sense, the role of academic elites is responsible for the spreading of ethnicist and racist discourses (Van Dijk, 2009; Jiménez-Rodrigo et al., 2009).

7In the case of the used labels to identify, diagnose and help students with special education needs "NEE" or "ACNEES" and "ANEAE" or "ACNEAES" (students with specific needs of learning support).

8 The intersectional analysis' purpose is to avoid the traps of unidirectional definitions and dichotomous arguments, taking into account the construction of social experiences through the intersection of numerous gender, racial, class or national differences, leading to the rupture of a hegemonic ideal, of a homogenous "us" (Guzmán-Ordaz, 2015). Likewise, the examination of other kinds of theoretical and methodological contributions more distant from the positivist academic standards could contribute to broader perspectives in favor of more critical insights with prevalent essentialist ideas.

Received: October 22, 2014; Accepted: February 11, 2016

texto en

texto en