Introduction

Both the need to quantify the benefits that Protected Areas (PAs) provide to humans, and the morality of doing so, are controversial issues, as it is argued that unspoiled nature, health and human life are absolute, incommensurable values. Hence, any attempt to calculate the economic impacts generated directly or indirectly by PAs may be considered unnecessary or even unethical. Moreover, evaluation in general monetary terms tends to disregard crucial aspects such as social justice and the distribution of costs and benefits among stakeholders (Young, 1992). Besides, market failures demand governmental intervention to assure long-term environmental conservation, regardless of economic consequences (Pearce and Turner, 1990). But these arguments fall short of the mark, for any decision-making regarding conservation policies (e. g., establishing PAs or accepting changes in land use) necessarily implies an -often tacit- cost/benefit analysis. Thus, politicians and senior officials are constantly determining the value of nature through the political measures they take, or refuse to take, so monetary evaluations of the ecosystem services provided by PAs simply uncover implicit assessments and assigned priorities in regard to conflicting uses of resources (Mayer, 2013).

In this context, Pascual et al. (2010) point out several reasons to assess the values provided by PAs: first, the evaluation of direct use values such as nature-based tourism leads to comparisons of different -and often conflicting- land use options in monetary terms, thereby enhancing knowledge-based decision-making processes. But more importantly, the unvalued benefits of PAs and other kinds of public goods are likely to go unnoticed and so tend to be underestimated, especially when they conflict with potentially unsustainable forms of resource use (Aylward and Barbier, 1992). Second, quantifiable information on the benefits of PAs makes a good case for procuring political support for their continued existence, aside from ethical considerations (Pearce and Moran, 1994; Primack, 1995). If the economic impacts of ecosystem services become known, then PAs are much less likely to be considered “black holes” that absorb scarce financial resources, but generate no discernible economic benefits. Third, economic evaluations will help to advise local stakeholders, government officials and the general public on the monetary costs related to collapsing ecosystem services due to environmental degradation (Dixon and Sherman, 1990). Finally, quantifiable economic benefits generated by nature-based tourism generally enhance the acceptance of PAs among local populations, as they might outweigh the costs of opportunity that arise from restrictions imposed on resource use (Moisey, 2002; Brenner and De la Vega, 2014).

Nevertheless, the quantification of the value generated by PAs entails several methodological challenges (see below) and so can provide only approximate numbers. Hence, the results of this study should not be regarded as a final or exclusive decision criterion applied to determine whether PAs are “useful” or not, but only as an additional factor that will aid in assessing the overall values -both tangible and intangible- that PAs provide.

According to Randall and Stoll (1983), the benefits of PAs can be categorized according to the concept of total economic value (considered as a comprehensive analytical framework for the economic valuation of nature’s benefits to humans). Pascual et al. (2010) define this concept as the total value of all services generated by nature at present and in the future. Consequently, total economic value refers to all use and non-use components of ecosystem services measured in monetary units (Mayer and Job, 2014). In this context, use values are sub divided into two categories: direct and indirect (Figure 1). Non-use values consist of existence and bequest values which are generally difficult to quantify in economic terms. Also, option1 and quasi-option values are difficult to classify, as they might refer to either use values or non-use values (Figure 1; see also Hanley and Barbier, 2009).

Sources: Mayer and Job, 2014, base don Barbier (1991), Munasinghe (1992), Job et al. (2009), Pascual et al. (2010) and Mayer (2013).

Figure 1 Total economic value of protected áreas.

Direct use values result from: a) the economic impacts of public investment in PAs (i.e. park management or infrastructure works); b) the productive use of PAs (e.g., agriculture, timber extraction); c) the economic impact of nature-based tourism (i.e., lodging expenditures by visitors; see Moisey, 2002); d) the value of recreational experiences;2 and, e) intangible direct use values (e.g., use of PA labels for marketing, infrastructure effects, etc.). These direct use values are generally measurable in economic terms since they are tradable in formal markets. However, reliable data are often lacking (Chape et al., 2008).

In contrast, the indirect use values of PAs are associated with certain ecosystem services,3 such as biodiversity, naturally-occurring air and water purification, or CO2-sequestration, etc. (Pascual et al., 2010). These ecosystem services share the characteristic of being public goods, but are more difficult to evaluate since effective market forces generally fail to operate freely due to state interventions or free rider problems, among other factors (Farber et al., 2002).4

Due to the methodological challenges involved in valuing indirect use and non-use values, and the controversial debate surrounding non-use and option values, the monetary quantification of direct use values, especially those of nature-based tourism, has now become a key issue in the field of environmental studies and policies (Chape et al., 2008).

However, the aforementioned benefits come with considerable costs. As Dixon and Sherman (1990) point out, three categories of costs may hamper both the acceptance and effective management of PAs: i) direct costs (e.g., administration, payroll); ii), indirect costs ( e.g., damage caused by wild animals); and, iii) costs of opportunity (e.g., income lost due to bans on fishing). The latter can be further sub-divided into losses related to limitations imposed on traditional resource use (e.g., timber extraction or hunting), on the one hand, and, on the other, restrictions on more capital-intensive uses of certain ecosystem services, such as generating hydrological power. It is also important to note that costs of opportunity are usually borne by local communities living inside PAs or in close proximity to them (Job and Mayer, 2012), a circumstance that can create trouble spots that affect public support for conservation policies (Brenner and De la Vega, 2014).

In many cases, tourism generates the lion’s share of the direct use value generated by PAs (Mayer, 2014). For example, Newsome et al. (2002) estimate the share of ecotourism (including whale watching) in overall international tourism expenditures at about 20%. This high proportion is due to the fact that many PAs are important tourist attractions, and that some, including El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve (EVBR), are considered unique because they offer visitors inimitable experiences. Consequently, the direct use value induced by nature-based tourism might foster economic development in PAs and surrounding areas (Woltering, 2012; Arnegger, 2014). This way, income from adequately-managed nature-based tourism could offset some of the costs of opportunity that PAs generate. There is also evidence that the tourism-related income that accrues to local stakeholders propitiates broader support for PAs while mitigating resistance to restrictions imposed on local communities (Brenner and De la Vega, 2014; Job et al., 2013). Given these facts, it is somewhat surprising that few systematic studies have been conducted to provide reliable data on the economic impact of tourist activities in Mexican PAs, with Arnegger’s (2014) study on Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve being a notable exception. Therefore, we have ventured to make the first move by addressing the following questions: a) what is the direct economic value (measured in terms of gross turnover) of whale watching (WW) generated by visitor spending in EVBR, a World Natural Heritage Site that has become one of Mexico’s prime nature-based tourism destinations; b) what is the spending behavior of specific visitor segments?; c) what types of local and non-local businesses benefit from this?; and, d) what effective means are there to increase the economic benefits generated by WW?

The paper begins with a brief description of the study area, focusing on the evolution of WW at EVBR. This is followed by an explanation of the methods applied to evaluate the direct economic value generated by WW, based on a representative survey conducted during the 2006-2007 season. Our results emphasize that visitor spending generates considerable gross turnover that benefits local tourism businesses, albeit spending behavior varied markedly among different visitor segments. The article concludes with some proposals for increasing the benefits of WW as a means of fostering sustainable and socially-balanced regional economic development in central Baja California.

1. Whale watching in El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve

WW is becoming increasingly important in global tourism (Gallagher and Hammerschlag, 2011; Cisneros-Montemayor et al., 2010; Orams, 2013, 2002; Hoyt, 2001), as its economic impact now constitutes an important motivating factor behind nature conservation and the imposition of bans on whaling (Bailey, 2012; Parsons and Draheim, 2009; Higham and Lusseau, 2008; Herrera and Hoagland, 2006). As a non-consumptive and potentially sustainable activity, WW aims to reconcile the protection of marine mammals with the needs of local people in terms of offsetting costs of opportunity (Hoyt, 2005a). As the primary hibernation and mating area of Pacific grey whales (Eschrichtius robustus) EVBR is now a well-known tourism destination, whose shallow waters often allow close-range WW from late December to early April. Occasionally, visitors are even able to touch those cetaceans (Parsons et al., 2003; Ritter, 2004). Due to these conditions, it is no wonder that in 2006 about 85% of all whale watchers in Mexico were registered in the peninsula of Baja California, most of them in EVBR (Hoyt and Iñíguez, 2008).

EVBR is the largest Protected Area in Mexico (25,468 km²; 3,624 km² core zone and 21,844 km² buffer zone). It is located in central Baja California State (Figure 2) (INE, 2000). As early as 1972, Laguna de Ojo de Liebre (LOL) was established as the world’s first Marine Protected Area in order to conserve the natural habitat of cetaceans (Hoyt, 2005b). From December to April, LOL and San Ignacio Lagoon (SIL, under legal protection since 1979) are mating sites for as many as 2,000 grey whales (Miller, 1975). In 1980, the nearby Guerrero Negro Lagoon was also declared a Protected Area, and eight years later these three whale sanctuaries were combined and enlarged to establish EVBR (Hoyt, 2005b). Since they constitute a crucial habitat for the entire grey whale population, the lagoons were declared a World Natural Heritage Site by Unesco in 1993 (Dedina and Young, 1995; INE, 2000). The area is sparsely popu-lated (1.84 inhabitants per km²) (Inegi, 2014) due to the extreme aridity (50-70 mm per year) of the region, which virtually impedes agricultural use if irrigation is not available (INE, 2000). Nevertheless, large-scale common property units called ejidos (based on extensive cattle-raising) and privately-owned ranchos (producing capital-intensive, export-oriented and irrigation-dependent crops) were established in the 1970s through grants of government-owned lands and agricultural subsidies. The latter tend to deplete the scarce groundwater resources (Brenner and De la Vega, 2014). In addition, large fish stocks triggered the establishment of several fishing camps at the reserve’s western seaboard since the 1950s, which evolved into rural communities such as Bahía de Tortugas, Bahía Asunción and Punta Abreojos (see Figure 2). As a result, the current economic structure of the EVBR area is characterized by large-scale salt production at the state-owned salt works (Guerrero Negro), irrigated export-oriented agriculture near the town of Vizcaíno, and seasonal WW at LOL and SIL (Figure 2). Small-scale fishing (especially crayfish and lobster) and livestock rearing are other complementary economic activities (see Brenner and De la Vega, 2014; Brenner and Job, 2012; Young, 1999a and b; Ortega-Rubio et al., 1998 for further details). As a consequence, different stake-holder groups claim the natural resources of EVBR, tour operators among them. However, this paper focuses on the tourism-driven direct economic value generated by the users of the reserve’s maritime diversity.

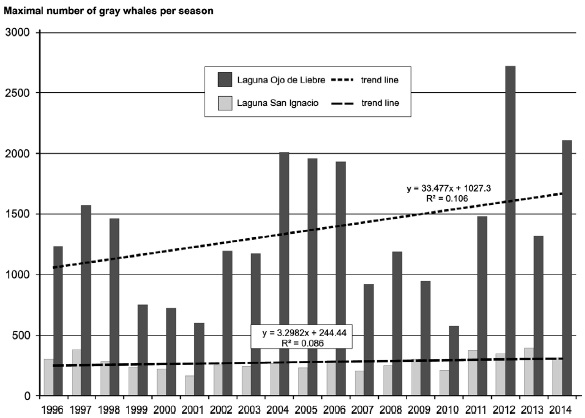

With respect to management efficiency, one striking fact is that the number of grey whales that hibernate and mate in EVBR has increased over the last 15 years, though naturally-occurring fluctuations are evident (Figure 3). This could be related to measures taken by the National Commission on Protected Areas (Conanp) since the late 1990s (Brenner and De la Vega, 2014). The stability of the grey whale population can also be considered evidence of the long-term environmental sustainability of WW (Heckel et al., 2001).

Source: elaborated by the authors base don data from Conanp, 2014a.

Figure 3 Number of grey whales in the EVBR lagoons, 1996-2014.

WW-related tourist activities in EVBR began to develop in the early 1970s when several operators from San Diego (California, USA) began to offer boat tours to LOL and SIL. Back then, WW was controlled mainly by US-based tour operators, as virtually no tourist infrastructure was available locally (Dedina and Young, 1995; Hoyt, 2005b). Since the mid-1990s, a growing number of visitors have reached EVBR overland by RV or car, on their way from the U.S. border to destinations in southern Baja California (or vice versa), an itinerary popular with retired North American tourists in wintertime. While passing through the Reserve on the only paved highway in central Baja California, most tourists use their necessary stopover to hire a WW tour as an “add-on” activity on their way south or north (Stadler, 2007). Consequently, as Figure 4 shows, increasing numbers of visitors at LOL and SIL were registered between 1995 and 2014. During the 2004-2013 period, numbers averaged around 18,000 visits per season5. In the 2006-2007 season, when our visitor survey was conducted, Conanp counted 17,903 arrivals, of which 10,595 went to LOL, and 7,308 to SIL (Figure 4).

Note: visitor numbers for the 2009-2010 season are not available.

Source: elaborated by the authors base don data from Conanp 2014b.

Figura 4 Number of whale-watcjers in the lagoons of EVBR, 1996-2014.

The increase in tourist arrivals spurred the establishment of several locally-owned lodging facilities and tour operators at Guerrero Negro and San Ignacio. However, income generated by WW remained marginal until the mid-1990s, as “benefits (…) remain[ed] insignificant in economic terms (…)” (Breceda et al., 1995: 24). Likewise, Dedina and Young (1995) and Young (1999b) concluded that, despite the increasing numbers of visitors, WW continued to provide only additional seasonal income, of which only a “very small proportion (…) remains in the communities involved” (Young, 1999b: 606). Indeed, this author estimated that at the time only 1,2% of total expenditures by whale watchers on package tours at the SIL was spent locally (Young, 1999b).

At first, there was little control over WW activities, but the EVBR administration gradually managed to regulate boat traffic on the lagoons and the use of fishing gear and nets at LOL and SIL. Finally, in 1991, locals were granted exclusive rights to offer tourist services at both lagoons, as a “trade-off” for the ban imposed on fishing in the lagoons during the tourist season. Since then, foreign tour operators have been legally obliged to hire local boats and guides (Dedina and Young, 1995); a measure that has enhanced community involvement in WW, as local fishing cooperatives and entrepreneurs opened up businesses to offer visitors tours, food and accommodation (Young, 1999b; Hoyt, 2005b). Agersted (2006) notes that between 1994 and 2002 visitor numbers increased by 50%, tourism-related employment by 100%, and revenue from local tourism enterprises by 70% (considering an inflation rate of 55%). By 2004, five locally-owned companies were offering WW tours, camping and lodging facilities, food, and transportation. In 2007, EVBR encompassed 53 accommodation businesses with a total of 1,448 beds, concentrated in Guerrero Negro (16) and San Ignacio (9).

However, if we consider the ratio of the number of beds per 1000 inhabitants (“tourist intensity”) as an indicator of the relative economic importance of tourism at the local level, tourist activities are significant to the local economy of San Ignacio (which serves as a “hub” for visitors to SIL), and -to a considerably lesser extent- in Vizcaíno, Punta Abreojos and Guerrero Negro (Figure 2). During the 2006-2007 WW season, a total of seven tour operators (three private businesses, three local fishing cooperatives and one ejido) offered WW tours in LOL, while six privately-owned tour operators offered their services at SIL. However, despite the increases in visitors and tourism facilities since the late 1990s, WW is still far from being the primary source of income for the local population (Agersted, 2006), simply because WW is a highly-seasonal activity: 75% of visitors register in February and March when the grey whale population in the lagoons peaks (Figure 5). Thus, WW depends heavily on the opportunity to observe close-up a large number of grey whales.

Note: no monthly WW data available for 2004-2005 or since 2005-2006.

Source: elaborated by the authors with data from Conanp 2014a and b.

Figure 5 Seasonal variation of whale watching in El Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve.

Unfortunately, there are no precise, up-to-date figures on the current economic impact of WW at local or regional level, though Hoyt and Iñíguez (2008) note that 15 tour operators operating in EVBR generated expenditures of $750,000 USD in 2006. According to these authors, some additional $8,274,000 USD were spent by visitors, bringing total expenditures to $9,024,000 USD. Such study has several shortcomings, however: first, the amount of visitors’ spending or “indirect expenditures” (no less than $475 USD/visitor/day) that they assumed (2008: 8) is not supported by any survey data and is only a rather rough estimate;6 and, second, they do not determine the distribution of revenue among the service-providers involved, which would shed light on the social dimension of the economic benefits generated by WW. Hence, the economic impact of WW in EVBR remains largely unknown. In addition, no studies have yet been conducted to calculate the leakages and multiplier effects generated by WW.

2. Visitor types and gross turnover

2.1. Methodology

The results of the present study are based on a visitor survey conducted in 2006-2007 (late December-early April), designed to calculate the gross turnover of whale watchers based on the expenditures of both overnight visitors and day-trippers who participated in guided tours at LOL and SIL. A random sample of 382 whale watchers was interviewed during, or after, WW tours in relatiFon to trip motivation, expenditures, and social and demographic characteristics, using standardized questionnaires. The interviews were conducted on 42 survey days during the entire whale watching season, scheduled ex ante according to statistical data provided by the EVBR administration.7 Survey sites were selected to ensure a representative sample in terms of visitor structure.8 Survey data were extrapolated to the total amount of visitors, based on weightings of the proportions of visitors registered at each lagoon. As entrance fees have been charged consistently during the WW seasons ($3.82 USD/person in 2007), reliable total visitor numbers are available from 1995-1996 to 2012-2013.

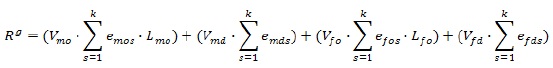

Estimates of gross tourist spending Rg by whale watchers were based on the methodology applied by Mayer et al. (2010). The number of visitor segments, their respective length of stay, and their mean daily expenditures per person were considered as follows:

2.2. Visitor types

Whale watchers are mainly working or retired adults, mostly US citizens (56,8%).9 Due to the distance to the mainland and the high cost of trips, only one-fourth (23,4%) of respondents were Mexican nationals,10 while the rest (19,8%) were from other, mainly European, countries (16,6%). Thus, incoming tourism is clearly prevalent at EVBR. In addition, 91,1% of respondents travel in groups (couples, families or organized tours) that average 3,47 persons.

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of respondents. The vast majority (86,7%) were overnight visitors (i.e., those who spend at least one night in EVBR), compared to 13,3% day-trippers (i.e., those who spend the night outside EVBR).11 The average length of stay of all over-night visitors in EVBR is 3,42 days. Foreign overnight visitors represent the largest segment (68,3%). As expected, the share of Mexicans among day-trippers is considerable (36,8%), but less significant among overnight visitors (21,3%). Nevertheless, Mexican overnight visitors tend to stay longer at EVBR (4,14 days) than foreigners (3,22 days). Four out of five respondents visited the Reserve on their own (i.e., no travel arrangements made prior to arrival), whereas 20,4% hired package tours from home, operated mainly by US-based companies.

Table 1 Whale watchers in EVBR (length of stay and travel arrangements).

DT: day-tripper; OV: overnight visitor.

Source: survey by authors.

With respect to the key motives for visiting EVBR, one-third (32,1%) of respondents stated that the EVBR’s status as a world-famous Biosphe-re Reserve and World Natural Heritage Site was particularly important (Table 2); a finding that suggests that using the labels “Biosphere Reserve” and “World Heritage Site” could lead to more effective destination branding in the future.12 However, a large majority (67,9%) stated that the Protected Area status mattered little, though overnight visitors highly-attracted by BR tend to stay longer than other visitors (4,34 vs. 2,99 days).13

Table 2 Whale watchers in EVBR (travel motivation).

DT: day-tripper; OV: overnight visitor.

Source: survey by authors.

Clearly, the most important motive was WW. In order to classify respondents according to their affinity to WW, we used three distinct features: a) the relevance of WW as a motive for visiting EVBR (very important/ important/less important/not important); b) the relevance of EVBR as a destination (primary destination/“one among others”/brief stopover on way to a primary destination); and, c) ratio: length of stay at EVBR/total length of trip (0-49%, 50-74%, 75-100%). This allowed us to identify three types of respondents with differing degrees of affinity to WW:

“WW-only” (16,4%): WW is considered very important and the primary leisure activity; EVBR is the primary destination; visitors spend 75% or more of their available spare time at EVBR; almost a half travelled on package tours (42,9%).

“WW first-of-all” (36,3%): WW is considered quite important and the primary leisure activity; EVBR is one destination among others; 50-74% of available spare time is spent there; just over a quarter of this group hired package tours (28,1%).

“WW as add-on” (47,3%): All other whale watchers; only 7,2% hired package tours.

As Table 2 shows, almost half of the respondents (47,3%) are “add-on whale watchers”, but even so, over 52% classified as “whale-watchers first-of-all” (36,3%) or “whale- watchers only” (16,4%). These figures highlight the crucial role of WW as a trigger for tourism-related economic activities at EVBR and -in Leiper’s (1990) terms- a nucleus for a tourist attraction. Moreover, the importance of WW as a reason for visiting the Reserve correlates positively with duration of stay, as the “WW-only” overnight visitors remained in EVBR for 5,87 days, while the respective figures for “first-of-all” and “add-on whale watchers” were 3,08 and 2,89 days.14

2.3.Visitor spending and gross turnover

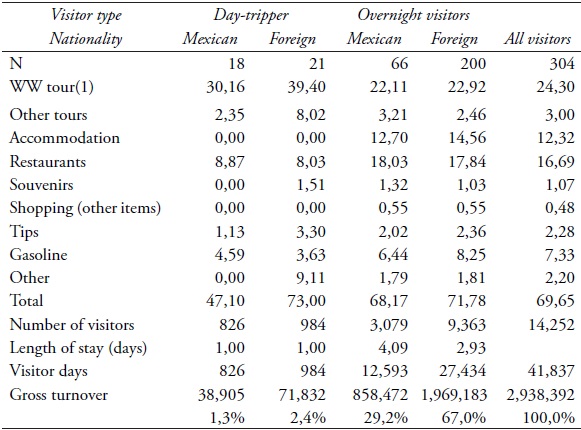

Table 3 shows the expenditures of (independent) whale watchers.

Table 3 Expendures of whale watchers (arithmetic means by visitor type/day) and gross turnover (in USD, not counting visitors on package tours)15

n = 304.

(1) Day-trippers spend more on the WW tours on a daily basis ($35,14 USD) tan overnight visitors ($22,72), because the latter stay for several days, though they take only one tour.

Source: author's research.

On average, respondents spent $69,48 USD/day at different locations in EVBR,16 of which 35% was for whale watching tours offered by local operators, 24,3% for food and beverages at local facilities, 17,7% for lodging (hotels, motels, camping facilities), and 10,5% for gasoline. In contrast to other studies (see Mayer et al., 2010; Arnegger, 2014), there were no statistically significant differences between the expenditures of day-trippers and overnight visitors.

Considering visitor numbers and types, daily expenditures per person, and length of stay in the survey area (see above), total revenue (or gross turnover) from whale watching tourism in EVBR was as follows (Table 3): WW generated a total gross turnover of $2,938,000 USD in the 2006-2007 season (not counting visitors on package tours). One-third (33%) of this amount accrued to local tour operators, 24,9% to restaurants at Guerrero Negro and San Ignacio, 19% to businesses that provide accommodation (19%), and 10,7% to gas stations. Clearly, WW is highly-dependent on North American and, to a lesser extent, European tourists, as more than two-thirds of the gross turnover is generated by foreign overnight visitors (67,0%). In contrast, less than 30% (29,3%) is spent by Mexican overnight visitors. Finally, Mexican and foreign day-trippers do not generate significant turnover (1,3% and 2,4%, respectively).

Visitors’ daily and overall expenditures differ according to their whale watching affinity, as on a daily basis the “WW-only” segment spends considerably less than the “WW first-of-all” and “WW as add-on” groups (Table 4). However, these results must be taken with caution because “WW-only” overnight visitors stay almost twice as long as the other segments. Thus, this group had the highest overall expenditures during their stay at EVBR ($267,20 USD), compared to $227,70 and $211,80 USD for the “first-of-all” and “add-on” whale-watchers, respectively. But due to their limited share among all EVBR visitors, the “WW-only” day-trippers and overnight visitors account for only 11,7% of overall gross turnover. In contrast, the “WW as add-on” segment generates 53,9% and the “WW first-of-all” group 34,5% of turnover. Consequently, “add-on” whale watchers should be considered the most important segment in economic terms.

Table 4 Expenditures (arithmetic means) and gross turnover according to visitor types and WW affinity (per person/day) (in USD, not counting visitors on package tours).

Note: Values sharing the same subscript are significantly different at p<0.05 (Tamhane test).

Source: author's survey data.

Excluding package tourists, Mexican day-trippers are largely overre-presented among the “WW- only” guests (24,3 vs. 5,0% in the total sample), which might explain their relatively low daily expenditures. The share of Mexicans in the “WW-only” segment is also above average in the case of overnight visitors (48,6 vs. 19,1%).

Discussion and conclusions

These results highlight several key issues. First, the direct use value (measured by total gross turnover) of just under $3,000,000 USD generated by independent WW triggers regional economic development at EVBR, since revenue accrues primarily to local tourism businesses at Guerrero Negro and San Ignacio. Privately- and community-owned tour operators benefit most from WW, followed by small and medium-sized enterprises that offer food, accommodation, and gasoline. One particularly striking fact is that visitors spend most of their budget on WW tours while accepting relatively inexpensive food and accommodation services. As a result, guided WW tours on the two lagoons are the main drivers of tourism-related revenue. In contrast, traditional services catering to visitors -such as hotels, motels and restaurants at Guerrero Negro and San Ignacio- are less relevant in terms of income generation, highlighting the significance that many respondents (especially the “WW-only” and “WW first-of-all” segments) attribute to WW as the motive for visiting EVBR. Hence, our results are contrary to Young’s (1999 b) study, which argues that only a small proportion of visitors’ expenditures remain in local communities. This important finding can be explained by the increasing involvement of local entrepreneurs in WW businesses since the late 1990s. Our results also prove that Hoyt and Iñíguez (2008) overestimated the amount of visitors’ indirect expenditures, which led them to overvalue the economic importance of WW.

Our study does have some limitations, as it does not consider the leakages that may result from inputs purchased outside the region (e. g. food, beverages, technical equipment), that would reduce impacts on the local and regional economy; nor does it contemplate the possible multiplier effects generated by tourist expenditures. Hence, further research is necessary to quantify the overall economic impact of WW at the local and regional levels. Also, additional surveys on multiplier effects and impacts on employment (beyond the topics studied herein) would shed light on the overall economic effects of nature-based tourism in Mexico.

Second, the gross turnover generated by WW at EVBR is considerable when compared to other Mexican nature- based tourism destinations. Applying the same methods as ours for the year 2006, Arnegger (2014: 157) calculated a total gross turnover of $4,500,000 USD in Sian Ka’an BR (Quintana Roo, southeastern Mexico), though most of the money (about $2,900,000 USD) was spent in adjacent tourist resorts outside the Reserve’s boundaries and so did not benefit businesses inside it. Moreover, average daily expenditures at that reserve ($18.28 USD) were almost four times less than in the case of EVBR ($69,48 USD). Though making direct comparisons between these two PAs is problematic because of disparities in their respective levels of socioeconomic development and visitor numbers (89,765 at Sian Ka’an vs. 17,903 whale watchers 17 at EVBR), the marked differences in these figures highlight the current role of WW as a trigger for regional development in EVBR, however additional comparative studies are required to gain insight into the impacts of WW at national level.

Third, evidence suggests that revenues from WW generate both active and passive support for EVBR. As Brenner and De la Vega (2014) demonstrate, tourism promotion by governmental institutions and effective law enforcement to regulate WW at LOL and SIL have been perceived as both successful and economically-beneficial by most actors involved in nature-based tourism. The qualitative in-depth interviews conducted by these authors revealed that most respondents considered these measures suitable for enhancing the quality of services offered by local tour operators, and thus lead to increased revenues. Accordingly, most tourism cooperatives and private service providers now accept the regulations and actively support most measures taken by the management authority (ibid.). It is fair to say that broad support for the current gover-nance regime depends at least partly on WW as an alternative source of income. Direct use value generated by WW has therefore fostered successful implementation of UNESCO paradigm of Biosphere Reserves in this area of Baja California.

Fourth, due to its notable impact on the economies of Guerrero Negro and San Ignacio, WW offsets, at least partially, the overall costs of opportunity related to the ban on fishing. Stadler (2007) estimates the income lost from the 4-month ban on rock lobster fishing in LOL during the whale hibernating season at approximately $400,000 USD. At the same time, the WW tour operators in LOL alone realize a gross turnover of more than $600,000 USD. Thus, the costs of opportunity related to banning lobster fishing are likely overcompensated by WW-induced in-come. However, more data on gross turnover in specific industries (i.e., fishing, agriculture, salt production, etc.) are required to assess in detail the scope and scale of the overall costs of opportunity that arise from restrictions on resource use, including possible trade-offs.

Fifth, revenue is generated mostly by North American overnight visitors with a specific interest in WW, so special attention should be paid to the “WW-only” and “WW first-of-all” segments, as they generate the bulk of expenditures. Also, these visitors are likely to spend more on additional WW-related leisure activities such as walking tours or scenic flights if they are available. Therefore, WW should be regarded as of special interest for incoming tourism which contributes not only to regional economic development, but also to increasing revenue from foreign exchange. While not comparable in terms of economic relevance with sun-and-sea tourism at Mexico’s major resorts, nature-based tourism in Baja California is broadening the range of the country’s export products and services. In this context, more data on specific visitor features would help to coordinate management activities at Mexico’s WW sites. Spending by Mexican visitors is noteworthy -though much less significant- since they tend to stay longer than foreigners.

We suggest funding further research in order to shed light on the features of specific visitor types and develop suitable marketing actions targeted to the three segments we have identified. Moreover, measures should be taken to increase the number of Mexican visitors, which would enhance impacts on regional economic development. In addition, other sights at EVBR -such as the cave painting near San Ignacio or the world’s largest salt production unit at Guerrero Negro- could be promoted more professionally to generate value from these unique tourist attractions. Finally, it would be helpful to quantify the direct use value of all economic activities present at EVBR, such as fishing, stock farming, irrigation agriculture and salt production. By applying suitable methods (an employment assessment might be the easiest way), this endeavor could provide specific information on the total use value provided by this reserve, as well as on existing or potential opportunity costs due to restrictions on resource use. In this spirit, a direct comparison of conflicting land use options in monetary terms would enhance a knowledge-based management of Mexico’s protected areas.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)