Introduction

This research addresses the quantitative and qualitative dimensions of green public space (GPS) in Mexico City as a case of environmental injustice. The article begins with a review of a set of relevant studies on GPS distribution and access in order to establish a theoretical framework, methodology, and a background for the presented analysis. The quantitative account of GPSs in Mexico City is presented based on Environmental Justice studies contending that urban amenities (e.g. parks) are unevenly distributed and often biased against marginal populations (Bolin et al., 2000; Boone et al., 2009; Carruthers, 2008; Chiesura, 2004).

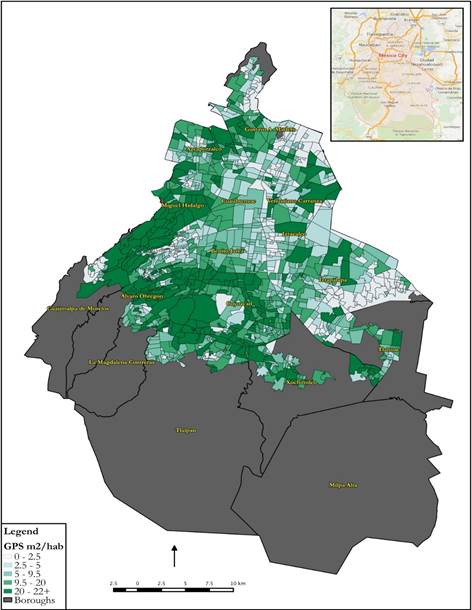

Methodologies proposed by Boone et al. (2009) and Talen (2010) to assess the socioeconomic status of population vis-à-vis distribution of GPSs were applied. Using data provided by the Environment and Land Management Agency for the Federal District (in Spanish, Procuraduría Ambiental y del Ordenamiento Territorial del Distrito Federal, PAOT) and National Institute of Statistics and Geography (in Spanish, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, Inegi), a series of maps were created to show Mexico City’s uneven distribution of GPSs in relation to the socioeconomic status or marginality levels of its population.

GPS maps presented in this work comprise only a selection of features included in data sets provided by governmental institutions due to the fact that official maps do not follow methodological criteria established in the Environmental Statement for the Federal District (NADF-006-RNAT-2004). The main difference between previous maps and those offered in this work is the criteria used to determine what is and what is not GPS. According to Mexico City Environmental Law, GPSs should be, in fact, public. All spaces accounted as GPSs for this research were contacted or visited to ensure the actual public character of each site. Whereas official documents considered airports, military stations, prisons and penitentiaries, private universities gardens, cemeteries, and even shopping malls as GPSs, this analysis focused only on spaces open to the general public for the purpose of leisure, physical activity, or any other not-for-profit activities.

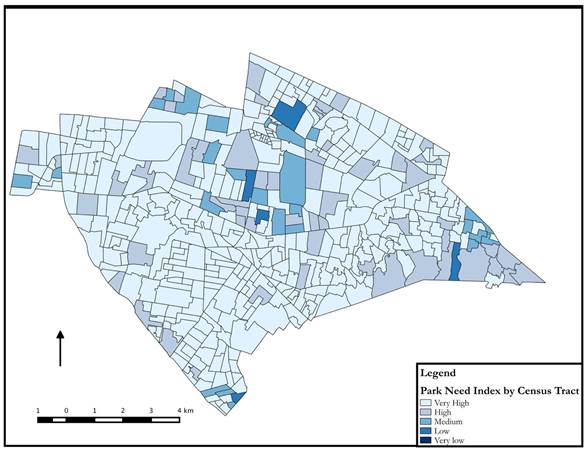

In addition, the article presents the basic socio-demographic deeply differentiated characteristics of Mexico City’s population (Aguilar et al., 2003) vis-à-vis GPS. Given that the most common form of GPS in Mexico City is parks (Wakild, 2007), a suit of variables proposed by the Population National Commission (in Spanish, Comisión Nacional de Población, Conapo) were integrated in the creation of a Park Need Index (PNI). Results shows that GPS distribution is biased against young population with low levels of education and high levels of poverty living in densely populated areas.

1. Green public space and environmental injustice in the city

Rodgers et al. (2012) documented processes of urbanization on an unprecedented scale in Latin America. In accordance with reports by international institutions such as the UN, WHO and World Bank, the authors confirmed that Latin America is the developing world's most urbanized region, with over 75% of its population currently residing in towns and cities. Hence, urban studies in the region have thrived focusing on the overall urban quality of life with a clear emphasis on urban inequality, widely recognized as central to many of the most pressing challenges in cities of the South (Samara et al., 2012). A robust body of Latin American literature regarding urban studies has investigated instances of environmental injustices in Mexican cities (Carruthers, 2008; Hardoy et al., 2013; Satterthwaite, 2003). Furthermore, urban environmental services and their contributions to air, soil, water, and general human and non-human wellbeing quality studies have been favored extensively in the region (Bigio and Dahiya, 2004; Coolidge et al., 1993).

Environmental justice research has examined the correlations between race and class and the equitable distribution of environmental risk as well as access to environmental amenities (Bolin et al., 2000) with the main objective to identify “who gets what and why” (Turner and Wu, 2002:4). Considering the recurrent uneven distribution of environmental amenities and hazards in cities around the world (Schweitzer and Stephenson, 2007), environmental justice theory postulates that the distribution of urban risks and benefits are disproportionally biased against non-white minorities (environmental racism) and lower socioeconomic status population (environmental classism). This theoretical assumption is well-suited to study green space in Mexico City as all 16 boroughs comprising the Mexican Federal District feature considerable economic, social, and demographic differences (Aguilar and Mateos, 2011; Mier-y-Terán et al., 2012). The question is if and which socio-demographic characteristics are influential in the distribution of green space in Mexico City, as suggested by environmental justice research.

It is important to underline that environmental justice extends beyond socio-spatial patterns. It has been proposed that incorporating three dimensions of justice: distribution, recognition, and procedure is the most suitable way to accomplish a “richer, multidimensional understanding of the different ways in which environmental (in)justice and space are co-constituted” (Walker, 2009:24). Therefore, environmental justice scholars have concluded that, in order to fully understand what justice is, it is necessary to analyze the legal, economic, historic, cultural, social, and political processes that result in urban landscapes (Schlosberg, 2004).

For the particular case of GPS studies, there exists a general scientific consensus that “besides many environmental and ecological services, urban nature [commonly in the form of parks] provides important social and psychological benefits to human societies, which enrich human life with meanings and emotions” (Chiesura, 2004: 130). In Mexico, studies have been conducted in the states of Veracruz (Hernández-Bonilla, 2005), Nuevo Leon (Flores-Alanís, 2005), Puebla (Gante-Cabrera de and Rodríguez-Acosta, 2009), State of Mexico (Avilés and Chaparro, 2010) and Mexico City (Flores-Xolocotzi et al., 2010) to assess distribution, access, and uses of parks and other forms of GPS. Most of the scientific work regarding this topic in Mexico inclines towards a natural scientific/technical approach. Therefore, a number of urban environmental management manuals and taxonomic descriptions of the flora and fauna of the city are available; however, the lack of studies analyzing the interface between human and non-humans with the environment is noticeable. In the case of Mexico City, data clearly shows green spaces are unevenly distributed; nevertheless, there is no information regarding green space distribution per habitant in relation to specific socio-demographic characteristics. International environmental justice literature offers abundant instances of research investigating on GPS and the correlation between quality of life in urban contexts. Parks have been identified as key components for a livable city (Garvin and Brands, 2011).1

Spatial analysis of distribution and access to GPS is commonly present in the literature given the fact that the vast majority of research is based on the observation that urban infrastructure is not evenly or equitably distributed in cities (Low et al., 2005). Consequently, assessing who gets what appears to be one of the main objectives of research done for the past ten years. The methodology to analyze the spatial features of GPS can be divided in two categories. The first category includes research that focuses entirely on analyzing the quantitative spatial data available for a given city without including its human dimension (Aziz and Hisham-Rasidi, 2014; Bjerke et al., 2006; Bowler et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2010; Nicholls, 2001). In a sense this type of research obscures the historical, social, and political extent of space and its use in cities. Functionalist or deterministic research lacks important qualitative data useful to identify actors and motives for urban planning and development. On the other hand, there is also research incorporating both quantitative and qualitative data to answer questions of inequality and environmental justice.

For example, Boone et al. (2009) presented a hybrid study of urban parks in Baltimore, MD. Their main objective was to examine the distribution of parks as a socio-environmental injustice. Authors measured “potential park congestion as an equity outcome measure” (Boone et al., 2009:767) using a park congestion indicator (PPC), defined as “the number of people per park acre (PPA) in a given park service area (PSA) if every resident were to use the closest park” (Boone et al., 2009:772). In addition, as a social component of their research authors included a historical-process analysis in order to expose the possible drivers responsible of park distribution and access patterns. Boone et al. (2009:783) concluded that

the story of parks in Baltimore illuminates the complex interactions between race and [urban] planning where efforts to segregate the city fueled fear and ignorance, and consequently white and later middle-class black flight to the suburbs, along with population and economic decline in the core […] Baltimore is now living and struggling with the legacies of segregation and environmental injustice.

Without fetishizing spatial data, authors’ conclusion casted light over the social production of environmental injustices. Studies offering quantitative data coupled with an analysis of qualitative evidence have had documented impact on public policy and other decision making processes in cities (Pincetl, 2003). For example, Sister et al. (2009) research goal was to develop decision-support tools to improve park policies, which could generate better funding allocation based on democratic and equitable principles. To do so, authors traced the historical emergence of parks in their research areas and the evolution of spatial uses/practices based on demographic features such as race and gender. Another significant illustration of merging qualitative and quantitative data into the creation of scenarios and criteria for governance is the work of (Pincetl and Gearin, 2005). Authors examined patterns of environmental services unequal distribution produced by years of social, economic, and cultural development biased against minorities. Setting the historical, geographical, and institutional context in which urban green space emerges is what allowed these authors to contextualize data in order to create useful tools for governance. Thus, this article aims to create a bridge between environmental and social studies in devising an approach that accounts for both quantitative and qualitative dimension of green public spaces in Latin American urban areas.

2. The quantitative dimension of green public space in Mexico City

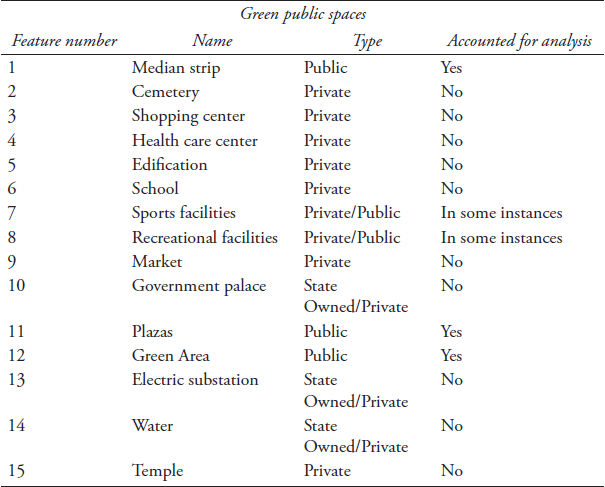

In 2009, the Environment and Land Management Agency for the Federal District2 (PAOT) presented a series of maps showing different aspects of environmental conditions in Mexico City including environmental risks, land uses, irregular settlements locations, and green areas distribution per habitant among others.3 Drawing from data provided by the Inegi and PAOT, using QGiS 2.4, this article presents a new map of green public space distribution per habitant per census tract. Inegi provided GPS data in the form of polygons including 15 urban features (table 1). However, not all of them represented GPS. For example, cemeteries, shopping centers, health care centers, some bodies of water,4 private edifications with green spaces, schools, markets, government palaces, electric substations, and temples are not open to the general public. Therefore, those features were not included in the present analysis. Moreover, some sports facilities and other recreational facilities were included after I corroborated their public status.5

Table 1 Green public spaces features account for distribution analysis

Source: Compilation and categorization by author, 2015.

Given the fact that a substantial number of features were not included in the creation of this new map, there exists a noticeable difference between the official maps by local governments and mine regarding green public space distribution. However, the original and most significant attributes of the map remain the same: the green area per capita map shows five different tonalities of green ranging from the lowest to the highest availability of green space; the lightest green represents the areas with less m2 of green space per resident (0-2.5 m2/hab) compared to the darker green showing the areas with higher per capita green space (20-22 or more). The present map is also representative of the unequal distribution of green public space among boroughs in Mexico City as it shows green space concentration in the southwest and center. East areas of the city are disproportionally “gray” or lacking green space (map 1). The category of urban green area is defined in the Environmental Statement for the Federal District NADF-006-RNAT (GDF, 2002) as:

Any surface covered with natural or induced vegetation, located on public property of the Federal District, and referred to in any of the categories provided in Article 87 of the Environmental Law of the Federal District. This category includes parks, gardens, garden or tree-lined squares, planters, plant cover any areas on public roads (roundabouts, medians, trees lining), avenues and groves, headlands, mountains, hills, natural grasslands, and rural areas for forestry production or ecotourism services, canyons and areas of aquifer recharge (Environmental Law of the Federal District, 2002, 14; translation by author).

This overly generous and clearly lax definition of GPSs by Mexico City’s governments serves to overstate the actual amount of GPS available in the city. Figures presented by previous administrations did account for private spaces, regardless of the contradictory official definition of GPS. As mentioned earlier, administrations have been using international standards to measure gains on GPS provision. For the Mexican capital governments, it has been of utter importance to project a progressive image. The current administration is following a questionable criterion by considering spaces with less than 160 m2 of vegetated areas established as the minimum for an urban space to be considered a GPS- according to the Article 88 bis of the Mexico City Environmental Law (GDF, 2002). Despite the fact that urban environmental governance in Mexico has shown positive advances since the late 1980s (Schteingart, 1989), current official quantitative reports on GPS provision in Mexico City are instances of local administrations trying to deceive the public by making up numbers that do not align with terms defined by local laws. Airports, military stations, prisons and penitentiaries, private universities gardens, cemeteries, and even shopping malls were considered GPSs in Mexico City reports whereas they are not included in this analysis (table 1). As an antecedent of this methodological inconsistency, (Rivas-Torres, 2005) reported that more than 44% of the spaces considered as GPS were only “grassed”, agricultural areas or not at all vegetated public spaces.

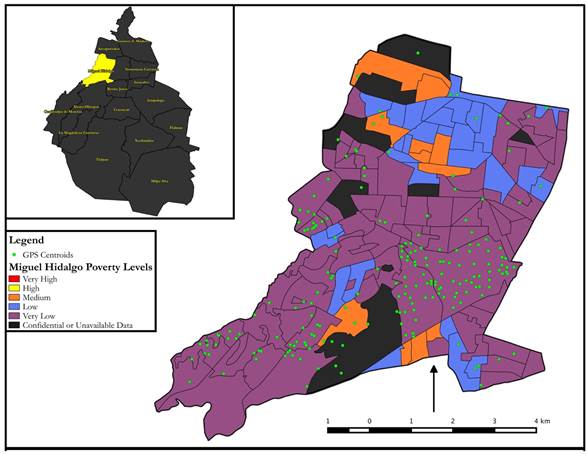

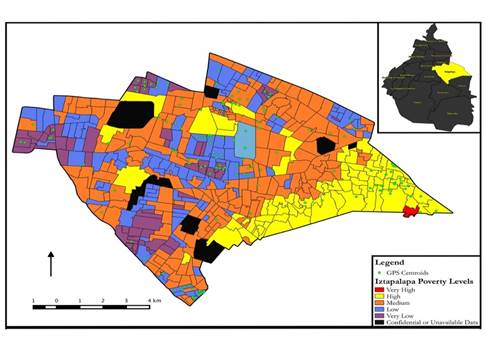

In addition to the distribution of green space among boroughs in the city, it is important to identify the specific socio-demographic attributes of those areas without green areas. Following the socio-spatial research by (Mier-y-Terán et al., 2012) in Mexico City regarding urban poverty, residential segregation, and public space, a map for this article was created using the Population National Commission (Conapo) ranks and identified the neighborhoods (in Spanish, colonias) with medium-high (yellow), high (red) and very high (dark red) poverty levels in Mexico City (map 2). Conapo ranks refer to a function that accounts for four different socioeconomic variables: education levels, access to medical services, housing conditions (i.e. owning or leasing properties, number of inhabitants per residence, etc.), and access to residential services such as sewer and potable water. We propose the creation of a park need index based on Conapo’s rankings for two fundamental reasons. On the one hand, Mier-y-Terán et al. (2012) previous work on urban poverty, segregation, and public space in Mexico City showed that the Mexican federal government uses these rankings to assess marginalization as an official standard to classify boroughs and neighborhoods or colonias. On the other hand, also according to Mier-y-Terán (2012:127), Conapo’s rankings are best suited for spatial analysis given the “ample number of socio- demographic variables accounted for and its rigorous and systematic procedures to determine population’s marginality”. In short, Conapo’s rankings take into consideration the largest number of variables to determine urban marginality using a reliable method; hence, it is the best proxy for our analysis. If compared to the previous map showing the distribution of green areas, it is clear that the southeast part of the city is not only an area with less green space but also the one with the highest levels of poverty.

Based on this simple observation, it can be deduced that the need for parks has to be measured based on socioeconomic features of the population and not GPSs distribution alone -as the correlation is evident. For instance, the borough of Iztapalapa shows particularly high levels of poverty that have been associated with insufficient or non-existent basic urban infrastructure, substandard housing, high levels of unemployment or underemployment, and social stigmatization (Mier-y-Terán et al., 2012). Furthermore, as showed in map 2, Iztapalapa also presents a very low concentration of green public spaces,6 an essential urban amenity.

The concentration of green public spaces in Mexico City is evident. Nevertheless, a detailed account of the socio-economic characteristics of those areas in the city enduring the lowest levels of GPS concentration was lacking. Therefore, using census data, Inegi’s GPS data and Conapo rankings a Park Need Index (PNI) for Mexico City was created. The PNI was used in this article as a proxy for urban socio-environmental injustice. It is important to highlight that, as reported by Kitchen (2012), parks are not necessarily an amenity for all dwellers as their characteristics can differ significantly. Furthermore, I acknowledge that lack of parks is not as adverse as lack of potable water. However, based on decades of research establishing the importance of social and environmental services provided by green public spaces, authors have argued that biased provision of urban amenities against marginal populations is a symptom of a structural condition that restricts pauperized urban dwellers from inhabiting livable urban spaces (Heynen et al., 2006; Loughran, 2014).

Needs-based assessments of parks have also been conducted in the past aiming to address issues of equity rather than equality7 (Talen, 2010). Following Boone’s et al. (2009) and Talen’s (2010) research, this article presents the Park Need Index as description of socio-economic and environmental characteristics of different areas in the city (table 2). Using Jenks natural breaks, variables were divided into five classes and then each census tract was assigned a corresponding value from one (very high need) to five (very low need). map 2 shows the summed values of all variables for the entire Federal District. Results show that there is a distinct lack of parks in the large majority of Mexico City’s boroughs given the proposed variables. Furthermore, it is evident that some boroughs such as Coyoacan and Miguel Hidalgo -both with very low levels of poverty- are currently enjoying a higher number of parks. In fact, 77% of census tracts in Mexico City presented a very high need for parks and only 2% a very low need for parks given the used criteria for the analysis. In the case of “very low need tracts” 1005 were concentrated in areas with very low poverty levels.8

The contrasting distribution of parks in Mexico City is noticeable in an overall sense. As a further matter, if addressed in detail, the socioeconomic characteristics of boroughs are correlated to a lack of parks. In areas with low income, less educated and younger people parks are scant. In contrast wealthy, older, and more educated populations have numerous parks available; yet, the use of parks in affluent areas of developed countries like the USA have been reported to be rarely used compared to marginal areas (Heynen et al., 2006). Heynen et al. (2006:12) indicated that: “As with other housing amenities, households with higher incomes tend to have greater disposable resources that can be used for tree planting and maintenance. Hence, upper income residences tend to have more, and better maintained, canopy cover on their properties” -and, as a result, less need for a green public space. Likewise, several authors have published research on developing countries and its urban populations unveiling the enormous gap between wealthy and marginal populations’ accessibility to private recreation centers for exercising and leisure; seclusion and a sense of exclusivity has been reported to be preferred over public spaces by the most affluent urban populations, whereas minorities and marginal groups are constantly demanding green public spaces (e.g. Connell, 1999; Janoschka and Borsdorf, 2004).

3. A socio-environmental analysis of green public spaces in Mexico City

Regardless of the current inequitable distribution of green public spaces (map 5), there is an absence of academic and political conversation regarding the injustices of disproportionate allocation of green spaces to an extremely small population group in mexican urban contexts. It is rather urgent to determine the guidelines that will inform the creation of parks in Mexico City based on equity over equality criteria. Equity in the distribution of GPSs has been discussed in the past (Nicholls, 2001) and regardless of its clearly subjective nature, open to multiple, sometimes competing, interpretations (Symons, 1971) there exists a standard adoption of the concept in urban contexts (Wicks and Crompton, 1986:204). Nicholls (2001) explained:

A compensatory, or need-based, approach to equity implies, as (Lucy, 1981, p. 448) notes, ‘that unequals should be treated un-equally’. Thus, disadvantaged residents or areas are awarded extra increments of resources, so as to provide these groups with opportunities that they might not otherwise have had.

Therefore, in order to redistribute GPSs in a compensatory manner it is important to assess “Who gets what?” or, normatively, “who ought to get what?” (Wicks and Crompton, 1986:342). The analysis presented in this article identified “disadvantaged” populations based on socio-economic characteristics of age, income, population density, and area of residence. While comparing the poorest (Iztapalapa) and wealthiest (Miguel Hidalgo) boroughs in Mexico City a series of steep socio- environmental differences are observable. For instance, Miguel Hidalgo, a borough with a relatively small size (26,96 km²), medium population density, very low poverty levels and a highly-educated population hosts 197 GPSs. Conversely, Iztapalapa, a larger borough in size (117 km²) with the highest population density in the entire Federal District, very high levels of poverty and ruinous lack of access to basic social services accounts for 133 GPSs.

In addition, taking into account the PNI analysis done for the entire city (table 3 and map 6), Iztapalapa and Miguel Hidalgo are almost exact opposites while compared. On the one hand, Miguel Hidalgo presents a low to very low need of parks per census tract. On the other hand, Iztapalapa presents a high to very high need of parks per census tracts in the large majority of its area. However, it is noticed that even in Miguel Hidalgo the need of parks is ample. From a total of 11 census tracts, 109 (93%) were graded as having a very high need of parks and only two (1,7%) were graded in low or very low need of parks (map 3 and map 4). Even the wealthiest borough of the city presents a severe concentration of parks biased against populations with substandard socio-economic characteristics. In this regard, Iztapalapa presents the worst condition (map 5 and map 6); from a total of 512 census tracts, 425 (83%) were graded as in very high need of parks and only five (0,9%) census tracts were graded as low. Considering that populations with a substantially higher level of pauperization (table 4) should be targeted as priority groups to be served, park inequality in Mexico City is extreme.

Table 3 Park need index distribution by census tracts

Source: Compilation and categorization by author, 2015

Table 4 Mexico City poverty levels

Source: Conapo, based on Inegi (2010) census data. Transcription and translation by author, 2015.

4. Intitutional legacies on the production of GPS

According to Boone et al., (2009:777)

a limitation of much environmental justice literature is the inference of process from pattern. Although the distribution of parks or hazardous facilities can suggest possible linkages between race and the location of environmental amenities or disamenities, to advance the science of environmental justice it is necessary to investigate the drivers or forces that generate those pattern.

Such drivers and forcers are embedded within historical processes that have resulted in today’s complex reality. Wakild (2007) disentangled the socioeconomic knots interwoven with historical decision-making processes that resulted in the emergence of urban parks in Mexico. According to her research, certain actors playing significant roles during the modernization era of Mexico and concomitantly Mexico City’s socio-environmental urban development, including green space distribution in the city, were determined. For example, Chapultepec Park located next to the Chapultepec Castle -whose construction started in 1785 under the administration of the New Spain’s virrey Bernardo de Gálvez in Mexico- evolved to become a space for the dominant classes and was successful in fulfilling economic and political needs.

On the other hand, the Balbuena Garden was designed for the marginal classes of the city, as a celebratory project for the centenary of independence. Against that historical background the emergence of new parks can be analyzed considering the main actors involved in envisioning, developing, and maintaining current urban infrastructure. Such is the case, for example, of the Bicentenario Park, located on the limits of Azcapotazlco and Miguel Hidalgo boroughs. Its very nature is sui generis given its origin as a political and environmental depletion mitigation tool (Fernández-Álvarez, 2012). The park was constructed upon a brown site that worked as one of the largest oil and gasoline refineries in the city for several years. Hence, these examples show the importance of unveiling the underlying historical and recent political, social, and economic factors that could be accountable or connected with the production of the uneven distribution of GPSs in Mexico City. Further research on this matter should be conducted in order to determine the origins and patterns of a seemingly institutionalized GPSs uneven distribution and it its negative bias against marginal populations.

Conclusion

Distribution of GPSs in Mexico City is severely biased against marginal populations. Evidence shows that socio-economic characteristics in the Mexican capital are directly related to the number of m2 of green areas available per person. GPS concentrates in wealthy areas of the city where older, more educated individuals reside. Conversely, densely populated areas with very high levels of poverty are acutely underserved. As explained earlier in this article, parks are the most common form of GPS in Mexico City and its distribution is also linked to population’s socioeconomic features. However, even in affluent areas of the city there exists a pronounced need for parks. That is not to say GPS deficit in the Federal District is in any way uniform; in fact, the unequal nature of GPS distribution is palpable and constitutes an undeniable instance of socio-environmental justice. A more sophisticated understanding of GPS equity in the particular context of Mexico City was an urgent scholarly and governmental task needed to advance efforts to reduce the gap between those with and without access to urban nature in the city. Nevertheless, GPS deficit and inequitable distribution cannot be addressed without transforming the structures that produce and perpetuate social and environmental injustices in the first place. Institutions in charge of managing GPS in Mexico City are responsible for a series of procedural injustices that prevent marginal populations of having access to space in the city. In the particular case of parks, the intrusion of private corporations -often in charge of providing financial resources for urban infrastructure- has been a major obstacle for the state to develop and maintain solid urban development projects that benefit those most in need (Fernández-Álvarez, 2012). The structural forces that set and maintain social, political, economic, and cultural relations in urban context must be revised.

Space in Mexico City seems to be following a commodification and privatization trend in favor of a group of national and international corporations seeking financial profit (Aguilar et al., 2003; Delgadillo-Polanco, 2012; Delgado, 2004). The creation and management of the most important GPSs in Mexico City is the result of companies investing private resources with the main objective of financial return prioritized over any environmental, social, or cultural need. This context renders state efforts to govern urban spaces ineffective or inexistent. A central characteristic of GPS in Mexico City is the ubiquitous presence of private capital used for public projects, an oxymoronic dynamic that results in the imposition of agendas established by a reduced group of beneficiaries at the expense of the large majority of the city dwellers.

Evidence suggest that the Mexican state is no longer independent, it is incapable of controlling public tax resources and its capability to create and maintain meaningful public projects has been severely eroded. For example, as discussed early in this article, the Federal District Environmental Law (FDEL) has been ignored since 2002. According to the FDEL starting in 2002, a yearly report on the evolution of green public spaces was responsibility of each borough in Mexico City aided by the Ministry of the Environment in the Federal District. However, there exist only one inventory of green public space for 2002 and no further account of these areas has been done for the past 12 years.

As proposed by Marxist political ecologists, the political economy of a state has a direct influence in the creation of tensions amongst urban dwellers and their environments (Harvey, 2010; Mitchell, 2003). Moreover, reducing the state participation in governance affairs, such as providing urban amenities, is a quintessential neoliberal goal. In the context of Mexico City and its GPSs, governmental institutions responsible for serving citizens have been substituted for neoliberal forces. Consequently, companies take over urban space and in order to commercialize it as a commodity to be bought by consumers. This insidious practice results in segregation of those individuals that are not capable of affording goods and services that are supposedly paid using tax money. Therefore, GPS deficit in marginal areas of Mexico City is the result of state institutions’ incapability to manage resources with a democratic social approach. With the state’s abrogation of responsibility, there appears no viable alternative but to succumb to private corporations’ impositions in order to obtain resources for public projects. Ultimately, the state’s dependence of private capital to secure governance yields uncontrolled corporative intervention. This intervention, as seen with the examined case studies, will inevitably result in replacing of social goals with private financial objectives and the perpetuation of social and environmental injustices.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)