Introduction

Knowing the potential repercussions of a contingency that forces children to stay at home all the time is a transcendental subject for the professionals who dedicate themselves to their care.

The coronavirus family are not a new group of viruses that affect humans1. The current epidemic is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2), named by the International Virus Classification Committee. This virus produces a disease that received its name from the World Health Organization2 on February 11, 2020, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Severe COVID-19 pulmonary disease in children is uncommon3. Neurological symptoms can be divided into three categories: (1) neurological manifestations of the underlying disease symptoms (headache, dizziness, consciousness disorders, ataxia, acute symptomatic seizures, and cerebral vascular disease); (2) symptoms of peripheral nervous system origin (hypogeusia, hyposmia, and neuralgia); and (3) symptoms of skeletal muscle damage, often associated with liver and kidney damage4, although data on severe neurological involvement are fortunately infrequent in children5.

Each country has considered its official infection figures to create contingency phases to manage the pandemic. In Mexico, on March 20, 2020, the suspension of classes was officially announced in every school in the country, which meant that children had to stay at home, regardless of the benefits or consequences that this national contingency would bring.

In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association6, trauma-related disorders and stressors are included in acute stress disorder (ASD) and adjustment disorders, which can occur after a disaster or a radical change in the pattern of activities. Other psychological and psychiatric conditions may also be observed, such as depressive episodes, anxiety disorder, insomnia, and even suicidal behavior7.

In children, we find the subtle (or sometimes not so subtle) symptoms that may occur due to confinement, in addition to those directly caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Due to different life circumstances, family behaviors and routines change to reduce childhood distress, minimize exposure to stimuli that provoke fear or anxiety, and relieve distress; this process has been called family accommodation8. One modification of family routines may be staying at home to work or canceling family trips. However, most of the time, these changes are not voluntary, as in contingency, and may play a positive or negative role: just as they may alleviate distress in the short term, they may maintain anxiety and avoidance in the long term in children8. Parental care is critical as part of any childs upbringing. However, some parents become overly vigilant and think that everything is a threat to their child. This parental behavior has been considered a behavior that causes a major neurocognitive factor in developing and maintaining pediatric anxiety disorders9.

Insomnia is a common symptom in children, which may increase in special situations where changes in established patterns occur. Insomnia is associated with a decrease in school performance and an increase in psychopathology10. Behavioral profiles associated with objective sleep duration have been studied in young children with insomnia symptoms, and sleep duration and various physiological changes such as increased cortisol have been associated. Some studies show that children with insomnia symptoms have more behavioral problems in general than control groups11.

In children in whom sleep duration is typical, insomnia has been associated with high scores of externalized behavioral problems, such as restlessness, inattention, impulsivity, irritability, mood changes, and school problems. Conversely, children with insomnia and short sleep duration are associated with a more frequent profile of internalized problems, such as anxiety or low mood11. These children show a lower quality of life associated with a higher risk of other medical conditions10.

The difficulties of not attending school are a problem that should be continuously monitored in children. Several factors can result in a child having a good educational level. Specific measures have been studied, such as the socioeconomic level (a factor that directly impacts the educational opportunities and offerings provided by schools, including the quality of their teachers), maternal education, and paternal education. These three events impact childrens educational level. If these factors are modified, they can have a negative influence. Differences in childrens temperament must also be considered when dealing with school learning12,13.

In countries where the death toll has been significant and continues to rise, there will be many children and young people dealing with loss and grief in addition to their already challenging circumstances. There are no easy answers, but parents and caregivers are expected to be vigilant and work with children to provide a high level of interaction and support them through this contingency13.

Methods

Scientific information on COVID-19 appeared in February 2020, and the number of publications has been vast. The majority has been shared online to accelerate awareness. The transmission of data has been second only to viral and human-to-human transmission.

To analyze the parents opinion of how confinement affected children, we conducted and shared a survey on Google Forms 2 months after the suspension of classes. The survey consisted of 12 questions and was addressed to parents of children aged 4-15 years, considering that they were the most sensitive population, and was sent by email, WhatsApp, and Facebook. The survey was active online for 7 days. The first response was received on May 20, and the last response was received on May 26. The questionnaire was elaborated to obtain the following information: if children had any problems, from the parents perspective, with emphasis on sleeping difficulties; how they were living their school life from home; how distance learning was working out; how the use of screens had increased (which we know is a problem at present); how confident and informed parents felt with the current information to return to everyday life, including the return to school, and when the ideal time to return to school would be; if they had to implement any activity to improve the childs quality of time at home; and finally, if they considered that the contingency could leave something positive for their children.

Results

A total of 4000 responses were obtained with the Google Forms count. Some of those who entered to respond did not answer all the questions (marked as no response).

The first question was related to the problems that parents had observed in their children during confinement. The most-reported problem was related to online homeschool, access to a computer and internet, a physical space, or the difficulty for pre-school children to be sitting in front of a computer for online classes. Difficulties with online homeschool were reported in 30.4% of subjects. We should remember that schools responses have been very variable, as no one was prepared for the contingency. In general, homework prevailed, but some with TV classes, some with sporadic online tutoring, and some with formal online classes every day. In addition to sleeping problems, these problems represent half of the difficulties encountered by parents in their children (Fig. 1).

Secondly, we explored the kind of sleep-related problems in children during the contingency. We know that frequent expressions of anxiety in children are sleeping problems, including insomnia, nightmares, and night terrors; in general, insomnia symptoms are associated with a wide range of behavioral problems in children11. One of UNICEFs first efforts to care for children during the contingency was to provide easy-to-understand material, in addition to not overexposing children to COVID-19 issues14. The percentage of sleeping problems reported by parents was 46.7%, mainly related to difficulty falling asleep. This finding may be related to the loss of sleep and wake times during the contingency rather than a purely anxiety-related issue. However, it could be a sum of several factors (Table 1).

Table 1 Sleeping troubles during the contingency in children according to their parents

| Possible responses | Number of answers* | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty starting to sleep | 1868 | 46.7 |

| None | 1446 | 36.15 |

| Awakenings at night | 286 | 7.15 |

| No answer | 198 | 4.95 |

| Nightmares | 82 | 2.05 |

| Night terrors | 56 | 1.40 |

| Bed-wetting | 40 | 1 |

| Sleepwalking | 24 | 0.6 |

*From a total number of answers = 4000.

The third question was related to the increase in using screens, which has been a growing problem in children worldwide and has influenced their motor and social development15. Approximately 11% of parents perceived an increase of screen use > 90% in their children, 31.3% have seen an increase of 60-80%, and 33% observed an increase of 30-50% of screen use (Table 2). A study published a couple of years ago reported that 34% of preschoolers have an electronic device with screens and that the 16-24 age group spends more time playing than sleeping15. Thus, a current concern is developing addictive behavior in children and young people, now known as screen dependence disorder15. Characteristics of this problem focus on reducing or stopping screen use, loss of interest in other activities, the continuation of the behavior despite consequences, lying to hide the behavior, and its use as an emotional outlet15. The development and maintenance of this disorder are related to a dysfunction of brain structures. Brain imaging studies have demonstrated structural changes in the white and gray matter in the prefrontal cortex and limbic structures and reduced frontostriatal neuronal circuits15. Although the use of screens increased during the contingency, parents should make sure that this situation will not be detrimental to their childrens future functioning and decrease this behavior as soon as the contingency is over.

Table 2 Screen time increase in children during the contingency, according to their parents

| Percentage of increase (%) | Number of answers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| From 30 to 50 | 1322 | 33.05 |

| From 60 to 80 | 1252 | 31.30 |

| From 10 to 20 | 563 | 14.07 |

| More than 90 | 440 | 11.0 |

| It has not increased | 247 | 6.17 |

| No answer | 176 | 4.4 |

*From a total number of answers = 4000.

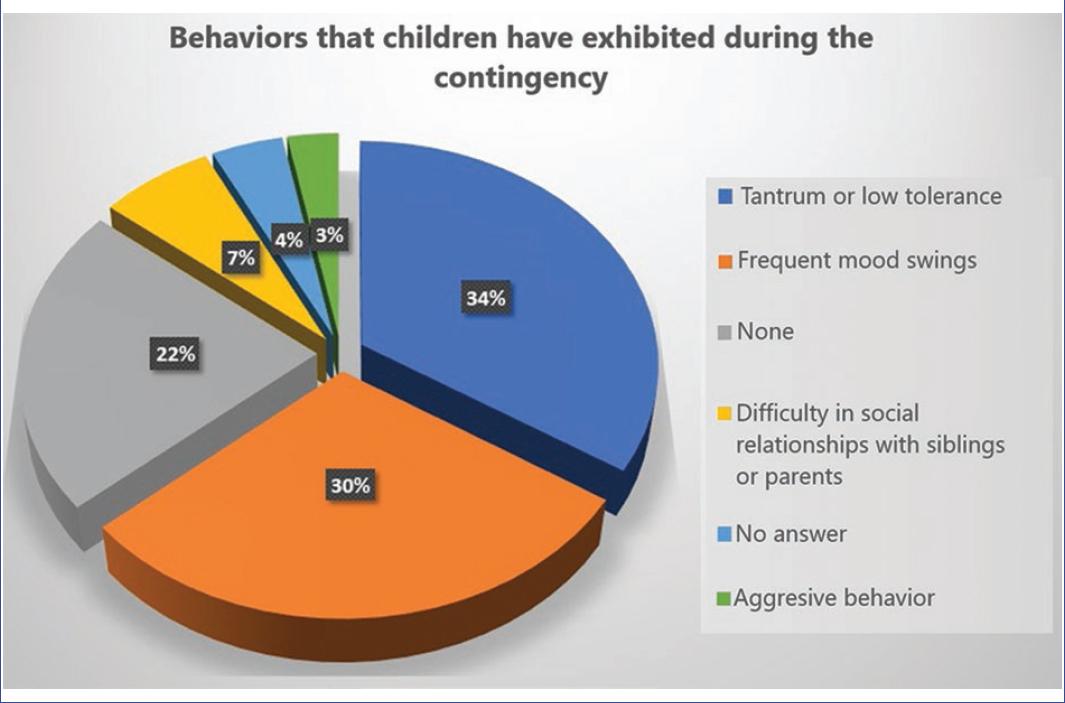

We also investigated childrens behavior during the contingency. Due to this situation, anyone may show signs of low frustration tolerance. As it is important to learn to postpone pleasure, we should recognize that many vulnerable children cannot handle stress13. The responses to this question are split into three possibilities of almost one-third of answers each. Tantrum or low tolerance was detected, followed by frequent changes in mood. However, more than 20% of the parents did not perceive behavioral problems, which was very good for this group of children who could handle the situation with no alterations (Fig. 2).

Regarding education, 77.8% of parents consider that distance education does not guarantee equal education for all children (Table 3). We know the economic differences and access to products and services in many families. Schools have tried to adopt different modalities that cope with the contingency. However, online classes require a computer and internet services, which is complicated for some children who do not have these requirements or even access electricity. In addition to these potential liabilities, families have been impacted socially and economically by the contingency13.

Table 3 Distance education and learning in children during the contingency according to the parental perception

| Distance education guarantees the right to education for all children equally | Do you consider that the quality of learning of your child has been the same with distance classes? | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Answer | Percentage | Answer | Percentage |

| False | 77.8 | No | 83.57 |

| True | 17.85 | Yes | 12.11 |

| No answer | 4.35 | No answer | 4.32 |

Concerning distance education, nearly 85% of parents consider that the quality of learning is not the same as face-to-face classes. We are used to in-person learning and supervision accompanied by teachers personalized guidance. Each childs temperament and learning styles are drivers of learning and educational success even with distance education13. Many families have complained, especially at the beginning of the contingency, about the enormous homework load. In the future, the mix of in-person classes can certainly be complemented by distance support (Table 3).

About returning to schools, 70.6% of the parents considered that it is not time to reopen schools, although 16.25% were not sure, while 9% considered that schools should be reopened (Table 4). These results suggest that parents may not be aware of the risks of opening schools at present, which implies bringing back groups of children and adults in a classroom together.

Table 4 Parents opinions regarding reopening schools and keeping schools closed during the contingency

| In your opinion, is it time to reopen schools? | Is there enough evidence to keep schools closed? | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Answer | Percentage | Answer | Percentage |

| Yes | 9 | Yes | 78.85 |

| No | 70.57 | No | 16.65 |

| Perhaps | 16.25 | Perhaps | 4.5 |

| No answer | 4.17 | ||

*From a total number of answers = 4000.

Furthermore, regarding evidence to keep schools closed, 16.65% of parents considered insufficient evidence to keep schools closed (Table 4). As a society, we need to receive clear information about the rationale for the closing, the risk of family mobility, the risk of children being infected, the risk that they may serve as vectors and transfer the disease to family members, and even the possibility that they may become ill and present severe symptoms (although this situation has been relatively infrequent)3,5. It is essential to be particularly careful with young children, as it is more challenging to maintain a proper distance, wearing masks, and maintaining hygiene measures in the classroom14.

Due to variations in official data and the unknown, the answers related to the ideal time to return to school are complex because no one has the absolute truth. However, 45% of parents believe that children should not return to school this year and almost one-fifth think that July 2020 could be an option for their return. Strikingly, almost 10% consider an option to repeat the school year, which would undoubtedly complicate the countrys school system (Table 5).

Table 5 Parents opinions on the ideal time to return to school

| Answer | Number of answers | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| In June 2020 | 226 | 5.65 |

| In July 2020 | 725 | 18.12 |

| Not returning this school year | 1798 | 44.95 |

| Repeating the school year | 353 | 8.82 |

| That everyone passes this school year | 704 | 17.61 |

| No answer | 194 | 4.85 |

The majority of parents took measures to improve the familys mental health during the contingency: strategies to entertain children at home throughout the day. We found that 51.3% have implemented games at home, which is a good strategy that also allows parents to observe the behavior of their children during an activity that involves rules and shifts; therefore, games imply working on tolerance to shifts, times, and the possibility of winning or losing. Physical exercise at home has been something that parents have engaged in almost 25% of the cases. We have long argued that engaging in physical activity can improve mood for several reasons, including endorphin production. It has been confirmed that more significant physical activity is consistently associated with a lower probability of developing depression and that the protective effect of physical activity is observed independently of age and sex, which is significant in all geographic regions16. Therefore, daily activity seems to be an excellent recommendation. In contrast, only a low percentage of parents have felt the need to seek professional help to improve mental health in their children (Fig. 3).

Regarding the next question, With the information you have, do you feel comfortable with restarting your daily activities?, we obtained a total of 2975 responses indicating that parents were not comfortable with starting their activities, which represents 74.4% of the responses. On the contrary, 849 participants (21.22%) indicated that they were comfortable. A total of 176 people did not answer this question.

Everybody is uncertain about the pandemic, how to reverse the contingency, how to do it, which places to avoid, and which will be the safest. Although general information has been given and we can establish that hospitals are undoubtedly the riskiest places2, we will certainly have to avoid crowded and poorly ventilated spaces. We will have to change some habits to return to usual activities, but the parents responses show that almost 75% are uncomfortable resuming their daily activities.

Finally, we wanted to know if the contingency left positive things to children from their parents perspective. Adaptability and family unity were the most frequent answers, followed by learning to manage tolerance. A low percentage expressed taking advantage of the time to acquire a new skill (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This survey has shown the difficulties parents have observed in their childrens behavior, learning, and emotional state at the beginning of the contingency. Regarding COVID-19, neither children nor adults know what is happening and what is coming concerning health, education, and economy. In general, children are afraid of the unknown or what they do not understand.

In a population exposed to potentially traumatic experiences, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and somatic symptoms can be triggered. Although most of them disappear spontaneously, a proportion could evolve into more serious mental health disorders17, such as ASD, which should be monitored in children during and after the contingency. Although almost 13-37% of individuals who underwent any stressful situation have been reported with ASD, this disorder depends on several factors. In 2017, Bryant mentioned that the temporary nature and different causes of this condition have made it difficult to obtain accurate information about the prevalence of ASD18.

Although anxiety is prevalent in the general population, including children, and can be initiated in stressful situations such as the pandemic, it often goes unnoticed and untreated19. If children are timely diagnosed and treated, the risk of anxiety persisting into adulthood can be reduced. Restlessness, irritability, or sleep disorders such as insomnia are data that may be present in generalized anxiety disorders20.

Anxiety diagnosis is based on clinical data since there is no biological marker, for which the clinicians clinical experience is significant9. Among other scales used to assess anxiety at any age, the SCARED scale for children21 explores some of the following items: When I am afraid I cannot breathe well, I cannot swallow food, or I get dizzy, which are somatization data; people tell me that I look nervous; or data related to sleep such as I worry when I have to sleep alone, at night I dream that bad things are going to happen to my parents, or at night I have nightmares that something bad is going to happen to me. Also, other data such as I sweat a lot when I am afraid, I worry that something will happen to my parents, among others. For this reason, these questions can be incorporated into the routine pediatric consultation when anxiety is suspected, even though a formal scale is not applied. These data are non-specific. However, if considered together, these data could lead to suspect anxiety in children9,21.

Stress directly impacts sleep, such as sleep reactivity, vulnerability to insomnia, and circadian disorders22. Sleep reactivity is the degree to which stress disrupts sleep, resulting in difficulty falling and staying asleep22. The neurobiological basis for sleep reactivity involves disrupted cortical networks, dysregulation in the autonomic nervous system, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, an axis involved in stress and anxiety22. Poor sleep quality and insomnia are associated with decreased school performance, increased psychopathology, increased risk of self-harm, and even suicidal ideation10. Treatment of insomnia should be a priority in children upon diagnosis, as chronic insomnia has explicitly been associated with increased health risk and interpersonal, psychological, and daily functioning10.

While it is true that use of screens and the internet has become indispensable to take classes or be in communication with other people, we should be alert with children since they can fall into excesses using these tools only to play. Internet gaming disorder has been documented, which is a severe disorder that leads to impairment in self-regulation, mood, reward regulation, problems in decision-making, and impact on social skills23.

In our country, previous studies have detected that over half of the population seeks self-treatment, even when they perceive that they have a severe illness, mainly if they live in poverty or rural communities24. Therefore, constant campaigns should be carried out to promote mental healthcare. For the management of children with adaptive disorders due to the changing situation, drugs may be used; however, in many cases, breathing techniques, relaxation exercises, or self-help techniques have been tested and proven to be sufficient12,25.

Moreover, creative approaches to staying functional during this confinement have emerged: people must find fun ways to express their confinement experiences and isolation at home13. Some studies have analyzed parenting during the contingency, what to do with childrens stress and the best measures to deal with it13. Some suggested measures to address the contingency are online soft skills programs, remote work capability, resilience-supported work guides, and monitoring of vulnerable children13.

Some limitations of this study were that the survey covered a pediatric population in a wide age range, and childrens behavior is not the same at different stages of development; dividing the responses by age group would allow finding specific differences. Furthermore, only one response option was allowed, and some people may feel the need to answer multiple responses. Finally, there may have been confusion about who should answer the survey in families with more than one child since it was established that only one person per device could answer.

Undoubtedly, many things will change after the pandemic, including modifications in our hygiene and cleaning habits at home, workplaces, and school, and encourage online meetings to reduce mobilization of people. However, the difficulties reported by parents in this survey should be monitored in the short, medium, and long term, as children could exhibit behavioral and mood changes or sleep problems, which could increase if not timely addressed. We suggest watching for feeding, sleeping, responses to external stimuli, tolerance to frustration, hand sweating, nail-biting, enuresis or encopresis, repetitive behaviors, easy crying, overly sensitivity, and mood swings. If these symptoms are observed, it is worthwhile to have them checked by a health-care professional.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)