1. Introduction

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith (1776) introduced the impact of envy on wealth distribution as follows: “The affluence of the rich excites the indignation of the poor, who are often both driven by want, and prompted by envy, to invade his possessions.” Although envy and constrictive and destructive activities associated with envy have been examined from different perspectives by scholars in varied fields, it may be argued that there are only a few economic studies which formally examine dynamics of envy and its impact on inequalities in income and wealth over time.

This study deals with interactions between envy and economic growth in dynamic general equilibrium theory. There are some studies on the economics of envy. Normative aspects of envy were examined by economists in welfare economics long time ago (Varian, 1974; Baumol, 1987). Behavioral implications of envy are studied by, for instance, Banerjee (1990) and Kirchsteiger (1995). Brennan (1973) examines how non-altruistic individuals can be motivated by envy to promote redistribution programs as the individuals value reducing the rich’s consumption. Banerjee (1990) examines how progressive taxation may be promoted to correct the distortions created by envy. Mui (1995) analyzes the economics of envy in the standard economic choice framework. The model examines how agents’ innovating, retaliating, sabotaging, and sharing behavior are determined by propensities for envy and other factors. As far as introduction of envy into formal economic modelling is concerned, this study is specially inspirited by a recent publication by Gershman (2014). In the Gershman model, if there are scarce investment opportunities, large inequalities, and insecure property rights, the economic system may be located in a fear equilibrium where richer agents underinvest because of fearing destructive factors due to envy of the poor. Otherwise, the economy follows the traditional “keeping up with the Joneses” competition where envy is satisfied with high efforts. This study emphasizes destructive side of envy and examines how destructive activities interact with dynamics of growth and income and wealth distribution.

This paper studies interactions between envy and economic growth in a general economic growth theory developed by Zhang. Zhang’s theory is an integration of Walrasian general equilibrium theory and neoclassical growth theory with Zhang’s utility function and concept of disposable income (Zhang, 2012, 2013). Walrasian general equilibrium theory was proposed by Walras and then generalized by many others (e.g., Walras, 1874; Arrow and Debreu, 1954; Debreu, 1959; Arrow and Hahn, 1971; and Mas-Colell et al., 1995). With regard to contemporary dynamic theory, the general equilibrium theory fails to properly analyze dynamics of stock variables, such as physical capital and human capital, with heterogeneous households. (e.g., Morishima, 1964, 1977; Jensen and Larsen, 2005; Montesano, 2008; Impicciatore et al., 2012). On the other hand, neoclassical growth theory is mainly concerned with dynamics of stock variables. Nevertheless, different from general equilibrium theory, neoclassical growth theory is weak at dealing with distribution issues among heterogeneous households (e.g., Solow, 1956; Burmeister and Dobell, 1970; and Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1995). Zhang (2012, 2013) has recently made efforts in building a general economic theory by integrating the economic mechanisms of Walrasian general equilibrium theory and neoclassical growth theory with applying Zhang’s utility and concept of disposable income. This study applies Zhang’s theoretical framework to study dynamic interdependence between envy, wealth and income distribution between heterogeneous groups (Zhang, 2012, 2013). The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we build the heterogeneous-household growth model with endogenous wealth and income distribution and with destructive activities of envy. In Section 3, we study dynamic properties of the envy-influenced economy and simulates dynamics of a three-group economy. In Section 4, we carry comparative dynamic analysis to show effects of changes in some parameters on transitory progresses and economic equilibrium. In Section 5, we conclude the study.

2. The Basic Model

The model developed in this section is built on Zhang

(2013). Following the Uzawa two-sector model (Uzawa, 1961; Burmeister and

Dobell 1970), we assume that the economy composes of capital goods and

consumer goods sectors. The population is classified into multiple groups. Group j’s

fixed population is denoted by

in which hj is the human capital of group j. The assumption of labor force being fully employed implies:

The capital goods sector

We specify the production function of the capital goods sector as follows:

where A i , α i , and i are the total factor productivity, and the output elasticities of capital and labor, respectively. Let (0< δ k <1) symbolize the constant depreciation rate of capital. We have the following marginal conditions for the sector:

in which w(t) implies the wage rate of labor. We have the wage rate for group j as follows:

The per household’s wage income W j (t) is

The consumer goods sector

We specify the production function of the sector as:

in which A i , α i , and i are the total factor productivity, and the output elasticities of capital and labor, respectively. We have the marginal conditions as follows:

Zhang’s Current income and disposable income

We apply the approach to modelling household behavior proposed by Zhang (1993, 2005). We apply

Different from the traditional concept of disposable income (which is the current income in Zhang’s approach), we calculate household j’s disposable income as the sum of the current income and the value of wealth:

Description of envy and its impact

With regards to envy and its impact, we base our approach on the model with envy in discrete time by Gershman (2014). In Gershman’s approach, the population over time is a sequence of non-overlapping generations, each generation living for one period. Each agent has a unit of time. Let K stand for the total endowment of the economy, which is assumed to be constant over time. The population is classified into the rich and poor. The wealth is distributed as follows: K p = λK and K r =(1-λ) K, where λ is the given distribution parameter. Each agent allocates the available time between producing and disruption of the other agent’s process. The destructive activity is due to envy. If agent i allocates a fraction d it of his time to disrupt the productivity of agent j, the latter retains only a fraction p jt of his final output

where is a parameter measuring the effectiveness of destructive technology. The utility function is specified as follows

where L it is work time and θ and σ are positive and less than one parameters. Inspirited by Gershman’s approach and some other models on envy, we assume that destructive technology f jq (t) is

where A jq are parameters, T jq (t) and k jq (t) are the time and the capital stock that household j uses to destroy wealth of household q. It is assumed that household q loses its wealth due to group j’s envy in the following way:

where

This implies that one should not lose what one owns. According to (10), group j’s per household total loss due to all the destructive activities of the society is

We assume a simplified form of possible disruption as envy can be conducted through different channels on various people. For instance, there may be “joint productions” in destructive activities in the sense that one action may have destructive effects on different groups. For simplicity, we are only concerned with destructive sides of envy. Envy and its destructive impact are related to various variables such as family background, individual human capital, education, social environment, education, networks and relations with celebrities, relative richness in group (Gershman, 2013). By the way our approach can also deal with other variables such as sympathy or hatred. If a rich group has strong sympathy towards the poor, it is possible for the rich to make efforts to help the poor. In our approach, this can be dealt with by taking Ajq as a negative number and making proper adjustments in the rest of the model. Taxation by the government may be technically considered as a special form of sympathy. Hatred may be modelled similarly as envy.

Budget constraints with destructive activities

The disposable income is used for saving and consumption. The representative household from group j would distribute the total available budget between savings s j (t), consumer goods c j (t), and capital for destructive actions. The household also loses wealth due to destructive activities of the society. The budget constraint means

Let T 0j stand for the total available time that each household from group j has for work and destructive activities. The available time is distributed between work and destructive activities

in wich

Envy and Utility functions

It is assumed that utility level U j (t) is related to variables c j (t); s j (t) and f jq (t) as follows:

in which ξ j0 represents the propensity to consume consumer goods, λ j0 the propensity to save, and w jq0 is group j’s propensity to destroy group q’s property. It should be noted that in the theoretical literature of economic growth and development, most of formal models is built on the Ramsey approach to household behavior. The heterogeneity between households is assumed due to differences in initial endowments of wealth rather than in preferences (e.g., Caselli and Ventura, 2000; and Turnovsky and Penalosa, 2006). This approach in the traditional approach explains, at least partly, why modern growth theories have little to say about implications of heterogeneity in households’ preferences. Zhang’s approach is an alternative approach to the traditional approaches, which make it possible to deal with different issues of economic growth and development with heterogeneous households.

Maximizing utility

Maximizing utility

where

Wealth accumulation

The change in wealth is equal to saving minus dissaving

Equilibrium conditions for the two sectors

For the consumer goods sector, we have

For capital goods market, output of the capital goods sector is used up for the depreciation of capital stock and the net savings. We thus have

in which

Full employment of capital

The two sectors and destructive activities fully use up the total capital stock K(t)

in which K j (t) represent the capital stocks that group j uses for destructive activities

We built the model. The model is structurally general in the sense that we can consider some well-known models, such as the Solow one-sector growth model (Solow, 1956), the Uzawa two-sector growth model (Uzawa, 1961), and Walrasian general equilibrium theory, in economic growth theory as its special cases. The new aspect of this study is the introduction of envy into neoclassical growth theory with heterogeneous households.

3. Dynamic properties of the envy-influenced growth model

As the dynamic system contains many variables and these variables are nonlinearly inter-related, it is difficult to obtain analytically dynamic properties of the model. Nevertheless, we now show that we can follow the movement of the system by simulation. Before stating the main result of this section, we define the following variables:

We also use Ω

j

(t) to stand for unique functions of z(t) and

Lemma

The following J differential equations determine motion of the economic system:

The other variables are uniquely related to z(t) and

From the computational procedure in the Lemma we determine the motion of the economic system. Simulation can be easily conducted for any number of households as we already provide the computational procedure. We now consider a three-group economy. The parameter values of the envy-influenced growth model are specified as follows: Ai = 1;3; As = 1; i = 0;34; s = 0;3; T0 = 8; k = 0;05;

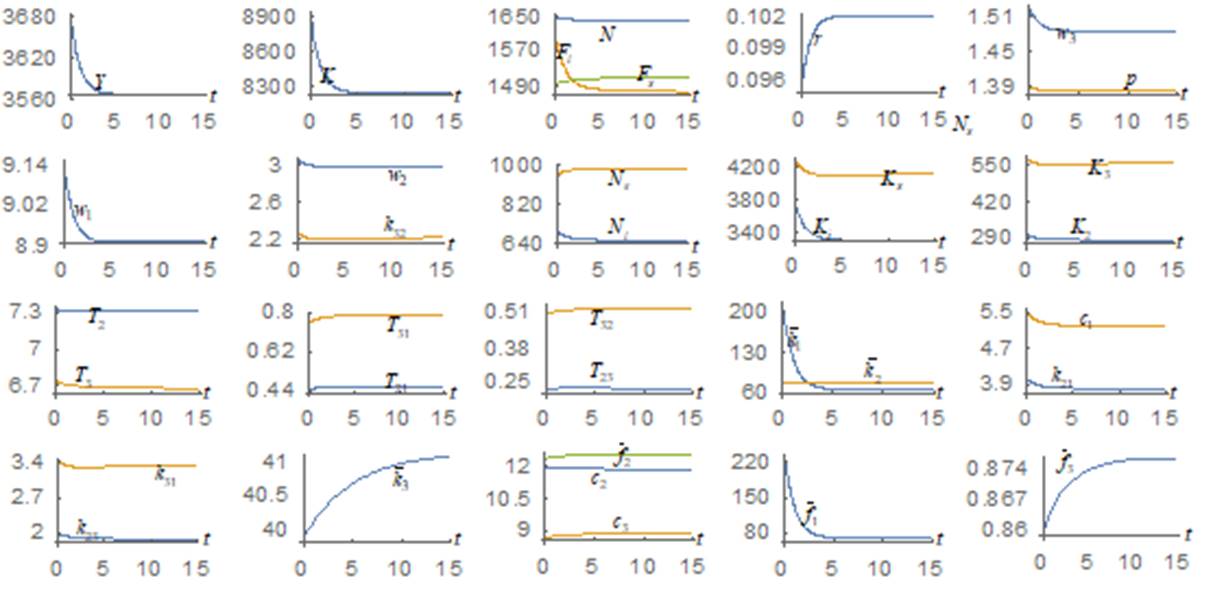

We assume the population of group 3 to be largest and the population of group 2 the next. We specify he capital goods and consumer goods sector’s total productivities 1.3 and 1, respectively. The values of the parameters j are approximately 0.3. The depreciation rate of physical capital is specified at 0.05. The initial conditions are

The motion of the variables is plotted in Figure 1. In Figure 1, the national income is

The national output, total labor supply and national wealth fall from the initial conditions over time. The output level of the capital goods sector is reduced, while the output level of the consumer goods sector is enhanced. The rate of interest rises as the wage rates fall. The price of consumer goods is reduced. Group 1’s per capita wealth, per capita consumption, and wealth are reduced by the other two groups’ destructive activities against group 1. Nevertheless, as group 1 has less wealth, the other two groups’ destructive activities become less effective. Group 2’s per capita wealth and consumption levels almost not changed. Group 3’s per capita wealth and consumption levels rise. The envy reduces the wealth gaps between group 1 and other two groups. The jealous groups work less and spend more time on destructive activities.

Figure 1 shows the existence of equilibrium point. We find the equilibrium values as follows:

We solve the three eigenvalues as follows:

The three real and negative eigenvalues. The equilibrium point is locally stable. This guarantees the validity of comparative dynamic analysis.

4. Comparative Dynamic Analysis

The previous section plotted the movement of the envy-influenced economy under (23). We now apply the computational procedure from the Lemma to make comparative dynamic analysis. This enables us to know effects of anon transitory processes and equilibrium. We use a variable xjt to represent the change rate of the variable, xj(t), in percentage caused by a change in the parameter.

4.1. The middle class enhance its destructive efficiency against the rich

We now consider the case that the middle strengthens its destructiveness against

the rich due to envy as follows:

4.2. The middle class enhance the propensity to destroy the rich’s wealth

We now study the impact of a change in the middle class’s propensity to destroy

the rich’s wealth as follows:

4.3. The middle class’s human capital is improved

We now study the case that the middle class’s human capital is changed as

follows:

4.4. The middle class increase the propensity to save

We study the case that the middle class augment the propensity to save as

follows:

4.5. The rich population is increased

We now deal with the case that the rich population is increased as follows:

4.6. The capital goods sector’s total factor productivity is enhanced

We now study the case that the capital goods sector’s total factor productivity

is changed follows:

5. Concluding Remarks

This study analyzed dynamic interactions between envy, economic growth and income and wealth distribution. We built a heterogeneous-household growth model with endogenous economic structure and envy. The unique contribution of this study is to examine the role of destructive side of envy on economic structural change and wealth and income distribution. The basic idea about modelling envy was inspirited by the literature of economics of envy. The motion of the envy-influenced heterogeneous-household is described by differential equations. We simulated the motion of a three-group economy. These groups are called the rich, the middle class, and the poor, respectively. We showed the existence of a locally stable equilibrium point. We conducted comparative dynamic analysis with regard to the middle class’s destructive efficiency against the rich, in the middle class’s human capital, the middle class’s propensity to save, the rich population, and the capital goods sector’s total factor productivity. We examined how changes in these parameters shift transitory processes and long-term equilibrium structure. For instance, our simulation showed that as the middle class increase the propensity to destroy the rich’s wealth, the effects on the economy are summarized as follows: (i) the national wealth, income and labor supply being reduced; (ii) the rate of interest is increased and the wage rates are lowered; (iii) both the capital goods and consumer goods sectors’ output levels and labor and capital inputs falling over time; (iv) the rich losing more due to the middle class’s destructive activities but less due to the poor’s destructive activities, the rich having less wealth and consume less consumer goods; and there being almost no change in losses in the long term; (v) both the middle class and the poor losing less due to the destructive activities, both the middle class and poor working less and using more times in destroying the others’ wealth; (vi) the middle class consuming less consumer goods and having less wealth; the middle class spend more time on destroying the rich’s wealth and less time on the poor’s; (vii) the poor spending more time on destroying the middle class and do not change the time on the rich, and the poor consuming more consumer goods and having more wealth in the long term; and (viii) in terms of consumption and wealth, the middle class and the rich suffer and the poor benefit. As our model is built in a very general analytical framework, we may generalize the model in various directions. For instance, we may take account of constructive side of envy in our modelling framework.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)