1. Introduction

The Great Recession opened a broad discussion about increasing banking regulation to mitigate future financial risks. Since then, global organizations and local governments have proposed a “macro” regulation for financial institutes, known as macroprudential policy, with the view toward preserving banking stability. Supporters of these tools consider that macroprudential regulation is the first line of defense for banking stability, preferable over the usual monetary and fiscal policies. Nevertheless, its use and assessment are pending, and empirical research about its effectiveness is still limited.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) consistently emphasizes among its members the main role of countercyclical capital buffers as an instrument to reduce credit bubbles that can produce economic crises (BCBS, 2009). Its proposals to strengthen the resilience of the banking sector include a reorganization of the national law for the coming years. Thus, diverse members had analyzed the local effects of implementing these proposals before incorporating them into their rules. One of its members is Mexico and several of its institutions had shown interest in this issue. In particular, the Bank of Mexico (Banxico) presented some information about the use of countercyclical capital buffers, given that there is no countercyclical regulation in the Mexican banking sector at this moment1. Banxico showed evidence that countercyclical capital buffers could have been used in 2007-2009 and 2013-2017 because of the high increase in private credit (Banxico, 2017a). Also, Banxico pointed out that more research about the consequences of the use of this regulation is needed to achieve a better conclusion about its effectiveness and social implications.

For this reason, the objective of this paper is to assess the quantitative effect of implementing macroprudential regulation in Mexico and verify whether these rules have potential economic benefits. Two time-varying instruments that respond to the credit-to-output ratio are analyzed: countercyclical bank capital requirements (CBCR) and countercyclical loan-to-value ratios (CLTVR). These rules are studied because they represent a simplification of other macroprudential tools that affect the supply and the demand for credits in a banking system2. The hypothesis behind why these instruments can have positive effects on the social welfare is the following: CBCR can force banks to hold more equity capital in the presence of a positive productivity shock so as to build buffers against losses if a negative shock hits the economy in the future. Thus, they must smooth a boom or limit credit growth beforehand as well as mitigate the adverse effects of a bust afterward. On the other hand, CLTVR can limit or encourage debtors in keeping a certain level of loans according to economic performance. So, CLTVR should avoid an excessive increase in loans when there are positive productivity shocks and facilitate credits in the presence of negative shocks. Therefore, CLTVR can potentially reduce bankruptcies, leading to a smaller macroeconomic bust.

This work analyzes the effect of introducing CBCR and CLTVR on social welfare using a general equilibrium model. Considering total factor productivity shocks and a second-order approximation of the utility functions, I find that there is a set of welfare-improving rules that enhance the economy compared to a situation where there is no macroprudential regulation. In particular, results show that these macroprudential rules are effective in keeping the debt level according to its long-term equilibrium, avoiding high and persistent credit cycles that could produce a banking crunch.

Relative to the previous literature, the main contribution of this paper is the analysis of CBCR and CLTVR in a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model where diverse welfare-maximizing rules are established numerically for different economic agents. Hence, this methodology allows setting a theoretical framework to analyze banking regulation for policy purposes in an emerging economy, combining financial frictions, macroprudential tools, and welfare evaluation. In particular, this paper is closely related to the study of Agenor and Jia (2020), Garcia-Barragan and Liu (2018), Roldan-Peña et al. (2016), and Sámano (2011). The first two papers described open economy models with banks and evaluated the welfare implication of the use of time-varying capital controls. On the other hand, the other two papers tested the effectiveness of a macroprudential tool and its interaction with the monetary policy for the Mexican case, using semi-structural models with a financial block. These papers found that a macroprudential rule, in combination with a Taylor rule, provides a better macroeconomic outcome than a Taylor rule alone.

In contrast, this methodology has some limitations. In particular, the model is not able to analyze the interaction between macroprudential tools and other policies. For instance, Alpanda et al. (2018), Bodenstein et al. (2014), and Carrillo et al. (2020) described the strategic behavior between monetary and macroprudential policies and showed that the lack of coordination leads to large welfare losses. Their findings emphasize the improvement in macroeconomic performance when there is a correct synchronization between both instruments. Indeed, Carrillo et al. (2020) found substantial gains in terms of compensating consumption variation from policy coordination, considering both social welfare and quadratic loss functions as payoff functions.

This work builds on the necessity of many policymakers to find solutions to new difficulties in financial performance, especially for emerging economies. Monetary and fiscal policies are poorly suited to achieving banking stability, and may even undermine it. Thus, macroprudential tools can provide a novel instrument to achieve financial and economic stability in complementarity with fiscal prudence and inflation targeting. In particular, for an emerging economy, macroprudential tools will become more relevant as its banking institutions grow, mainly because of the effect of technological innovations that facilities the incorporation of low-income individuals in the financial sector. Also, macroprudential rules have the potential to prevent financial imbalances and attenuate the impact of significant shocks. For instance, the current COVID‑19 pandemic represents the biggest shock to the global economy since the Great Depression and the emerging economies are already suffering its effects, so how much can macroprudential policy offset those effects? The full impact of the pandemic is still uncertain but an initial answer to this question can be analyzed for the Mexican case in the final section of this paper, showing how Banxico responded to the COVID‑19 pandemic with macroprudential tools as well as other policies.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a detailed explanation of the model, considering the banking features and the interaction channels between the credit and real business cycles. Section 3 seeks to identify the parameters consistent with the Mexican data. Section 4 explains the methodology to compute the welfare analysis. Section 5 analyzes the main results and Section 6 discusses the issues related to the implementation of macroprudential regulation in Mexico. Concluding remarks are contained in Section 7.

2. Model

The model is a DSGE model with real, nominal, and financial frictions, based on Alpanda et al. (2018), Gerali et al. (2010), Iacoviello (2005), and Lama (2011). It represents the main characteristics of the Mexican banking system and captures the dynamics of Mexican macroeconomic variables according to business-cycle fluctuations. With this model, it is possible to estimate an alternative situation where countercyclical macroprudential tools are implemented, comparing it with the current state in which there are no countercyclical policies.

Following Iacoviello (2005), there is a discrete-time, infinite horizon economy, populated by households and entrepreneurs infinitely lived and of measure one, who have different degrees of patience in their consumption preferences. The existence of diverse agents with different degrees of patience guarantees the flow of financial assets between them. In the model, households are the patient agents in the economy while entrepreneurs are the impatient representatives. Between them, as in Gerali et al. (2010), there are transactions through an intermediary, the banking system, which connects the financial resources between the offerors of savings and the credit claimants, making profits for those transactions. In this way, households grant financial resources to the banks, which use these assets to provide loans to entrepreneurs. Also, households offer their labor to entrepreneurs in return for a wage in order to satisfy their spending on consumption and savings. On the other hand, entrepreneurs convert their incomes and credits in consumption, labor hiring, and physical capital expenditures. Moreover, entrepreneurs buy and sell capital in a perfectly competitive market to the capital good producers, which have to pay adjustment costs whenever the investment is changed. Besides, entrepreneurs sell all their intermediate production to a sector of retailers, who have monopoly power and create differentiation in production prices, generating nominal rigidities as in Leith and Liu (2016).

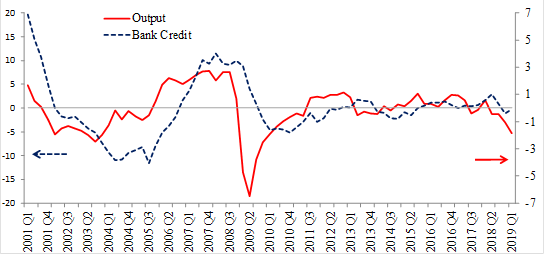

Additionally, as in Iacoviello (2005), entrepreneurs are subject to a collateral constraint such that the maximum amount of real credit depends on a proportion of the expected value of their net worth in the next period. This design allows linking the real variables with the financial ones through an extra constraint in their maximization problem, which also represents a financial friction. Therefore, there is a limit on their banking obligations considering their net worth, which depends on economic performance. In this way, the model captures the procyclicality of the banking system and, at the same time, the limitations faced by entrepreneurs when they require loans. For instance, the correlation between the GDP and the total financing to the non-financial private sector from commercial banks in Mexico is 0.35 from 2001 to 2019, such correlation can be appreciated in Figure 1. In addition, similar to Lama (2011), the model captures that the Mexican economy is a net debtor, so entrepreneurs have the capacity to borrow from abroad paying a risk premium3.

Note: Percentage deviations of its sample mean without trend.

Source: INEGI and Banco de Mexico.

Figure 1 Business and credit cycles.

In the financial part of the model, consistent with Gerali et al. (2010), the banking sector is divided into other branches: a wholesale bank and retail banks. The wholesale bank exchanges financial assets between households and retail banks. This sector has no profits and requires accumulating bank capital to provide credit to the retail banks, obeying a balance sheet restriction. On the other hand, the retail banks receive credits from the wholesale bank and give them to the entrepreneurs, charging them a differential in the net interest rates. This branch has market power, which ensures that the loan rate is always higher than the deposit rate. In this way, the banking sector has different interest rates at the same time, one interest rate for deposits and another one for credits. Thus, the model is able to capture the spreads that there are in the Mexican banking system. In addition, the model incorporates a central bank that sets the deposits interest rate according to the inflation and the output gap, following a Taylor rule. Figure 2 displays the dynamics of these two net interest rates in Mexico4.

Finally, similar to Alpanda et al. (2018), the model includes two simplified reaction functions that represent the countercyclical macroprudential policies and respond to the credit-to-output ratio: a rule for CBCR and a rule for CLTVR. The particular specification of these rules allows an examination of an alternative situation where countercyclical rules are activated in comparison to a benchmark economy, which has constant bank capital requirements and fixed loan-to-value ratios.

2.1 Households

The representative household

where

where

where

2.2 Entrepreneurs

The representative entrepreneur

where

Equation (4) represents the production

constraint where the final good

where

Inequality (6) represents the collateral

constraint where the expected value of the collateralizable physical capital stock at

period

Consequently, after substituting (4) in (5), the first-order conditions of the entrepreneurs are:

where

Nevertheless, since the collateral constraint is always binding, it is not possible to derive a simple expression between the local and the external interest rates. This happens because local and external debts are not perfect substitutes, given that local debt is subject to a collateral constraint, while the foreign debt depends on the total amount of the external loan7.

2.3 Capital good producers

Capital good producers are used as a modeling device to derive a market price for

physical capital, which determines the value of available collateral. They choose the

optimal level of investment and follow a law of motion for physical capital accumulation

that is subject to investment adjustment costs, as in Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe (2003). Following Gerali et al. (2010), capital good producers operate in a perfectly competitive market

and use final consumption goods to produce capital goods. At time t, they

buy

where

2.4 Banking system

As in Gerali et al. (2010), the banking sector in this model is divided into different branches, a wholesale branch and a loan branch. In this way, the model is able to separate the optimal decision on bank capital, according to the bank capital requirements, and the optimal spread that the bank system charges when setting interest rates, generating a differential between the deposit rate and the loan rate.

2.4.1 Wholesale bank

Wholesale bank acts as an intermediary between households and retail banks, operates in a perfectly competitive market and has to obey a balance sheet restriction

where

where

Subject to the balance sheet restriction, the wholesale bank chooses loans and deposits at time t to maximize the cash flow defined as

where

where

2.4.2 Retail banks

Retail banks are responsible for introducing market power that allows them to adjust

rates on loans to be greater than the deposit rates. Following Gerali et al. (2010), they are monopolistic competitors on the loan

markets, infinitely lived, and of measure one. At time t, they obtain

credits from the wholesale bank at rate

Households are the owners of this sector, so future profits are again discounted using the households’ stochastic discount factor. Therefore, the first-order condition is

The price elasticity of demand for

at the steady-state, implying that

2.5 Retailers

Retailers incorporate sticky prices into the model. According to Leith and Liu (2016), they are monopolistic competitors, infinitely

lived, and of measure one. Each retailer buys

where

2.6 Monetary and macroprudential policies

As in Gerali et al. (2010), the central bank set

the interest rate

where

where

In this paper, two main cases are analyzed according to the values of

2.7 Equilibrium

The profits of the entire banking system are defined as

the household sector is subject to the constraint

where the lump-sum profits from the banking sector and the retailers are now well defined9, and the total consumption is

Given that the model includes the households’ budget constraint, an equilibrium condition in the final good market is redundant. However, with equations (5), (18), (25), (26), and (27) at the steady state, it is possible to derive an expression of this equilibrium condition, which is equal to

Therefore, the equilibrium for this model is a set of sequences for the quantities

3. Calibration

The set of parameters is calibrated to match the main features of the Mexican data from 2001 Q1 to 2019 Q1 (in quarterly terms), considering the model equations at the steady-state.

The model integrates standard values for

For the reaction functions that represent the monetary and macroprudential policies, the

model incorporates the current banking regulation and the observed monetary policy reaction

in Mexico. Thus,

According to Lama (2011), for the parameters

associated with the foreign debt, equation (7)

incorporates a highly elastic supply of funds because its purpose is to induce stationarity

in the model rather than to capture the behavior of the risk premium, so

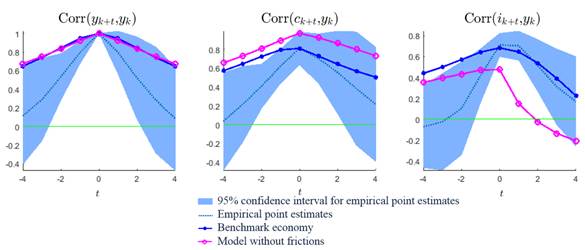

Figure 3 shows the dynamic cross‐correlations for the

Mexican data and the model. Two cases are displayed: a model without rigidities and a

benchmark economy where all frictions are activated. Both cases only consider productivity

shocks without macroprudential policy. In the case without frictions, the model does not

capture correctly the empirical correlation. In particular, the investment dynamics are

distant from the confidence interval for several correlations. On the contrary, the

benchmark economy performs better results as it gets closer to the data, especially for

Note: dynamic cross‐correlations are computed with a simulation of 10,000 draws where the first 10% of the sample was eliminated. Confidence intervals are consistent with the methodology of Christiano et al. (2014).

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 3 Dynamic cross‐correlations.

4. Welfare Analysis

The next step is to find numerically the adequate reaction that the macroprudential rules

must have. Thus, it is necessary to test the possible values that the parameters

The households’ welfare is calculated as follows:

1. Since the present discount value of the households’ utility function is

where

2. Ignoring

Therefore, the expected infinite discounted sum of the period utilities is

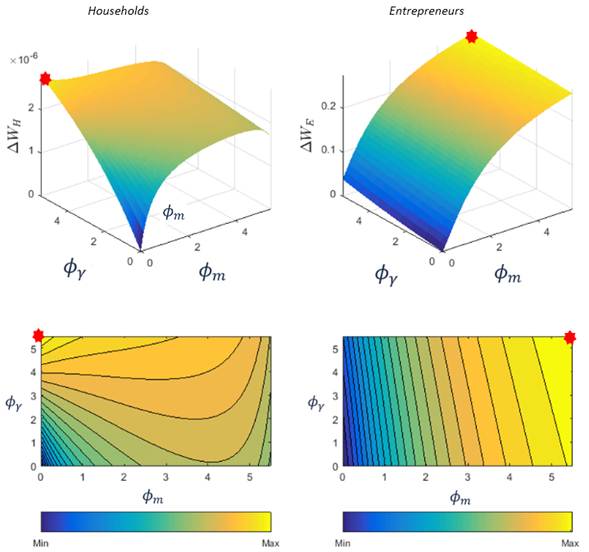

Note: The red star represents the pair that maximizes the welfare of each sector, which can be identified by being close to the yellow color and far from the blue color. Additionally, the contour lines are added to observe more details about the behavior of the percent change of welfare.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 4 Welfare evaluation.

3. Since

Therefore, to compute the households’ welfare under different policy rules, it is only

necessary to calculate the variances of consumption and labor across simulations of

productivity shocks and plug them into

Figure 4 shows the welfare’s percent change for each

agent, using each pair

5. Results

According to the previous findings, it is better to use

As a result, now it is possible to analyze how CBCR and CLTVR affect the economy and verify whether these rules meeting their goals of banking stability. This means that these instruments should smooth a credit boom (or a credit crunch) and avoid a situation where the economy is indebted beyond (or below) its long-term equilibrium.

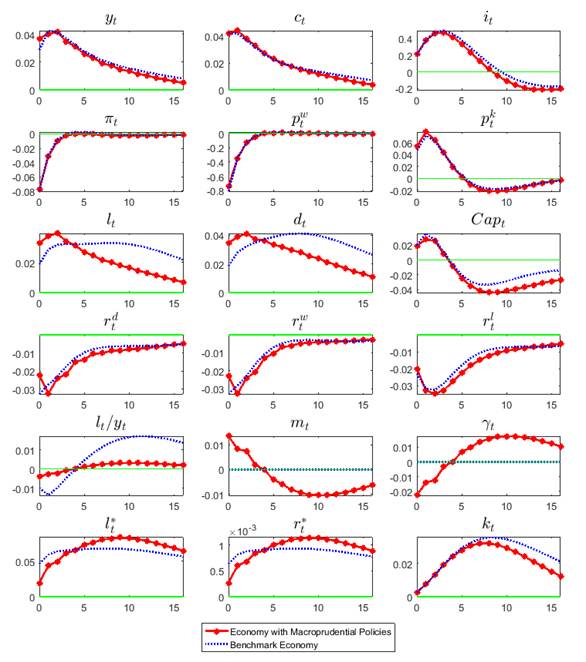

Note: All rates are shown as absolute deviations from steady state, expressed in percentage points. All others variables are percentage deviations from steady state.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 6 Impulse-response functions.

Figure 6 shows the impulse response functions of the

main model variables following a positive productivity shock for two cases: the current

banking regulation (i.e. the benchmark economy) and the alternative situation where the

countercyclical tools are activated,

On the other hand, in the alternative situation where macroprudential policies are activated (the red circled line), CBCR and CLTVR are successful in keeping the credit-to-output ratio according to its long-term equilibrium. Initially, during the first periods, CBCR and CLTVR facilitate the credit conditions to take advantage of the productivity shock. However, periods later, these rules restrict credit conditions to avoid a high credit-to-output ratio once the productivity shock diminishes. In comparison to the benchmark economy, the credit-to-output ratio falls quickly and mitigates the adverse effects of a bust afterward where the economy is heavily indebted. The intuition behind these results is the following: CBCR are efficient in keeping a stable credit-to-output ratio because they give incentives to households to save depending on the business cycle, while CLTVR motivate entrepreneurs to borrow according to the productivity shocks.

As a result, high credit deviations that could generate a banking crunch, which in turn

could create an economic crisis, are not possible because the credit-to-output ratio always

goes hand in hand with macroeconomic fundamentals. For instance, consider the entrepreneurs’

perspective under a positive productivity shock. Under the benchmark situation, in the

collateral constraint at time t, entrepreneurs can expand their production

and loans since the shock boosts the expectation of their net worth

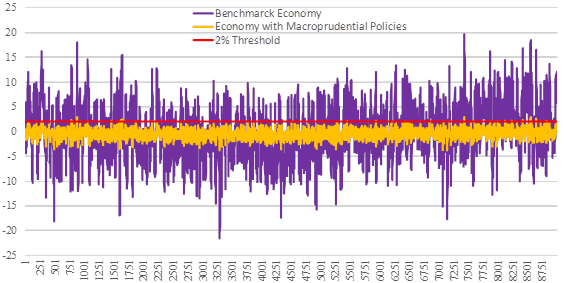

Regarding the creation of credit bubbles or high credit deviations, some additional clarifications must be considered. A credit bubble is a positive deviation in the relationship between credit and economic activity, and there are several methodologies that quantify it. For instance, Dell’Ariccia et al. (2012) provide a definition using the credit-to-output ratio that can be applied to a sample of 170 countries to identify the stylized facts that describe credit booms13. However, for the Mexican case and the BIS’ recommendation about the countercyclical capital buffers, a credit bubble is characterized when the credit-to-output ratio deviates positively from its trend by two percent. Therefore, an additional exercise is elaborated to show how the credit-to-output ratio dynamics change over time according to different banking regulations. Given a random path of productivity shocks, two simulated credit-to-output ratios are generated over time, one for the benchmark economy and another one for the alternative case. For the benchmark economy, there is a probability of 36.07% that the credit-to-output ratio excess the 2% threshold, which is consistent with the empirical behavior of the credit-output ratio deviations from its long-term trend (Banxico, 2017). In this case, the model produces credit bubbles because of the collateral constraint. This restriction specifies that the current value of the entrepreneurs’ debt grows according to the expected value of their collateralizable physical capital stock, which in turn depends on the contemporary investment. Therefore, when there is a positive productivity shock, there is an increase in the investment that produces a boost in the capital stock, which allows a persistent debt level and a positive credit-to-output ratio deviation for several periods. However, for the counterfactual case, CBCR and CLTVR do not tolerate significant credit-to-output ratio deviations, thus the creation of credit bubbles is very unlikely. In fact, its probability is equal to 0.6% in the model simulation. This exercise is displayed in Figure 7. Note that CBCR and CLTVR neither tolerate credit turndowns, showing their ability to deal with significant negative shocks, like the current COVID‑19 pandemic.

Note: Percentage deviations of its steady states. The exercise is computed with a simulation of 10,000 draws where the first 10% of the sample was eliminated.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 7 Credit-to-output ratio simulations.

As a result, CBCR and CLTVR are able to attenuate credit-to-output volatility because of two reasons. First, CBCR allow a persistent debt level only if there is a high accumulation of bank capital requirements, something that it is not possible because affects the banking sector’s profitability. And second, CLTVR mitigate entrepreneurs’ ability to preserve a high amount of loans because now the collateral constraint contemplates the loan-to-value ratio dynamics, which attenuates the effect of the expected value of the collateralizable physical capital stock over their debt14.

6. Policy Issues

There are some difficulties associated with the performance of time-varying macroprudential policies. Their implementation is not easy because of the need for detailed data about the banking sector and the real activity, the appropriate institutions, and the right policy rules to control the credit flows in the economy. However, despite all these complications, the use of the macroprudential tools in the Mexican economy is possible and several facts support this statement. In particular, the COVID-19 outbreak has accelerated the need to implement this new regulation, making this research highly helpful for policymakers during this pandemic.

The IMF has highlighted the Mexican progress to formally establish a financial stability committee to coordinate relevant information about the economy’s state between different regulatory agencies, laying the groundwork for the implementation of macroprudential policies (Carrière-Swallow et al. 2016). In 2010, Mexico created the Financial System Stability Council (CESF, for its initials in Spanish) with the objective to promote financial stability, avoiding interruptions, or substantial alterations in the functioning of the financial system and, where appropriate, minimize its impact when these take place (CESF, 2019)15. In particular, if any risk is identified in the financial system, the Council has the faculty to elaborate recommendations and act as a forum for policy coordination. Therefore, any type of macroprudential policy has to be approved and executed by this Council, considering at all times its congruence and coordination with other macroeconomic policies, especially with the fiscal and the monetary stance. As Guzman (2013) points out, monetary and macroprudential policies must work in a complementary way toward the achievement of their objectives and mutually strengthen one another.

On the other hand, it is possible to identify a situation when the economy or a specific sector is indebted beyond its capacity, considering that the main features of each loan in the Mexican banking system are measurable through the databases available for the Council16. For instance, if a response from the Council is required, one solution is to use the countercyclical tool for loan-to-value ratios that will decrease the ability of debtors to have high debt levels. This solution can be represented in practice by any regulation that changes the debt amount or the conditions offered by each bank, like collateral requirements, commissions, or other types of restrictions. Empirically, loan-to-value ratios are the most used tool according to Akinci and Olmstead-Rumsey (2015). They find that loan-to-value ratios are effective instruments for controlling credit levels, both for advanced and for emerging economies, especially for the housing sector.

Another solution that the Council can implement is the use of countercyclical bank capital requirements, which means changing the minimum capital requirements according to the business cycle without any limitations. Note that the rule of CBCR is different from countercyclical capital buffers (CCB), which is another instrument proposed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision among its members. CCB establish that countercyclical reserves must be created only during boom phases of the economic cycle and used during the downward phases. These capital reverses will react to credit-to-output ratio deviations in such a way that banks should only start to build up CCB when this indicator is greater than two percent (BIS, 2018). Therefore, the modeling of CCB is complicated because this rule reacts asymmetrically to the credit-to-output ratio considering a specific threshold. As a result, the proposed model in this paper can be a prototype to analyze CCB in a more complex setting17. For now, CBCR have already shown that they are effective in meeting their goals of banking stability and welfare improvement. Meanwhile, more research is needed to know the effects of implementing CCB. For instance, Carstens (2016) shows how CCB are particularly challenging in an emerging economy with low levels of financial deepening, mainly because the credit demand will grow beyond its current level, implying that the activation of CCB should not be guided exclusively by the credit-to-output ratio. Thus, CCB should be activated only when credit growth is driven by “supply factors” 18.

Amid the COVID-19 outbreak and related expected economic downturn, many emerging economies

are dealing with serious financial distress, requiring new instruments beyond the

conventional fiscal and monetary policies. For the Mexican case, on 04/09/2020, the National

Commission of Banks and Securities authorized banks to use their capital conservation

supplement to help their balance sheet19.

In terms of the model, this regulation implies that

7. Conclusions

This paper is the first attempt to analyze the welfare implications of countercyclical bank capital requirements (CBCR) and countercyclical loan-to-value ratios (CLTVR) in Mexico using a DSGE model, with the purpose to be useful in the public debate about macroprudential regulation. Using total factor productivity shocks and a second-order approximation of the utility functions, CBCR and CLTVR show their capacity to improve the Mexican welfare compared to a situation where there is no countercyclical regulation. In particular, CBCR and CLTVR facilitate or restrict credit conditions in order to follow the productivity shocks that hit the Mexican economy. This means that these rules are efficient giving incentives to savers and debtors to save and to get into debt only along with the productivity shocks, implying that it is not possible a situation where economic agents get an additional or less credit over their fundamentals. Therefore, the formation of credit bubbles that could generate an eventual banking crunch, which in turn could create an economic crisis, is not possible because the credit-to-output ratio always goes hand in hand with macroeconomic conditions. Also, in the case of a severe turndown of the economy, these rules show to be effective in facilitating loans to the business sector, independently of the reaction of the fiscal and monetary authority. Even though there are some difficulties associated with their use, nowadays there are sufficient conditions to use macroprudential tools. Results suggest that a countercyclical intervention in Mexico may well be needed in the near future and exploring alternative macroprudential policy responses is an interesting agenda for upcoming research.

In addition, results are useful to justify the implementation of time-varying macroprudential policies in Mexico. There are sufficient conditions to use CBCR and CLTVR since the legal arrangements, institutional design, and economic information are capable to allow an effective execution of these rules. CBCR and CLTVR represent a useful guide to recognizing the important variables and the main effects that policymakers should consider in real life. In particular, they should preserve the credit-to-output ratio according to its long-term equilibrium and look out its fluctuations according to the economic activity. Also, they should observe the accumulation of bank capital in order to avoid possible financial difficulties, as well as guarantee that there is an adequate debt level in the economy. Given the growth of the Mexican financial system in recent years, it is necessary to use additional measures that keep banking stability in the country, and macroprudential regulation can achieve this objective, especially during the COVID-19 outbreak.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)