Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.6 no.3 Tijuana ene./jun. 2012

Artículos

Transformations and Challenges of Argentinean Migratory Policy in Relation to the International Context

Transformaciones y desafíos de la política migratoria argentina en relación con el contexto internacional

Susana Novick

Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas/Universidad de Buenos Aires. Dirección electrónica: susananovick@yahoo.com.ar.

Date of receipt: April 6, 2010.

Date of acceptance: August 9, 2010.

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to analyze recent transformations in Argentinean migratory policies since the 2001 crisis, based on the state's passage of laws. The first part provides a brief historical outline approach as the framework and context for interpreting the present processes, their continuities and discontinuities. It emphasizes the influence of the international scene on the development of migratory policies—"denationalization" and "renationalization"—, and the social agents involved. The article ends with a description of policy progress and setbacks, including the challenges that must be faced.

Keywords: migration policies, legislation, international sphere, Mercosur, Argentina.

Resumen

El objetivo de este artículo es analizar las transformaciones recientes en la política migratoria argentina, a partir de la crisis de 2001, sobre la base de la producción normativa del Estado. En una primera parte se traza una reseña histórica abordada como marco y contexto en los que se interpretan los actuales procesos, sus continuidades y rupturas, subrayando la influencia del ámbito internacional en el proceso de gestación de la política migratoria –"desnacionalización" y "renacionalización"– y los actores sociales que intervienen. Por último, se presentan los avances y retrocesos en esa política, así como las dificultades que deben superarse.

Palabras clave: política migratoria, legislación, ámbito internacional, Mercosur, Argentina.

Introduction

Analyzing migratory policies in Argentina involves exploring one of the most crucial and hotly debated issues in its history as a nation. Migration is a phenomenon that has left a profound mark on Argentinean society. Virtually from the outset, the state began to concern itself with population issues, prioritizing migrations within its strategy. It needed to populate the country quickly, modernize it and import labor, which was crucial to implementing the dominant project: transforming its extensive territory into farmland to produce the food Europe needed.

The purpose of this article1 is to analyze the recent transformations in Argentinean migratory policy since the 2001 crisis, based on the state's passage of laws. Since a long-term perspective was used for this research, the article begins with a brief overview: from the First National Population Census in 1869 to the coup d'état in 1976 and from the coup to the crisis. And it was from that date onwards, when a point of inflection occurred, that different political experiences emerged and a new migratory law was sanctioned, constituting a record degree of progress in the issue. The first two periods are dealt with as a framework and context in which the current processes, their continuities and discontinuities, are interpreted. The theme of this study is based on the ideas put forward by Sassen (2001). We are therefore interested in exploring the tensions, ambiguities, and contradictions emerging between the control the state has exerted over those entering its territory and the constraints on their practices. Regarding the state's autonomy and sovereignty, we ask: a) Over the course of time, how are processes of "denationalization" on the part of Argentinean policy and "renationalization" on the part of migratory policy in particular developed and linked?; b) who are the social actors who participate in the formulation of migratory policy; c) what characteristics has the process of deterritorialization had in granting rights to migrants? We are therefore concerned with finding out the extent to which the transformation of Argentinean migratory policy has been influenced by the international sphere.

In order to answer these questions, it is useful to observe the evolution of Argentinean demography, which has shown historic trends: low total growth, early fertility reduction, early population ageing, a stagnated decrease in mortality, high urban concentration and a decrease in the influx of migrants (Mazzeo, 1993). At the same time, since the 1990s, there has been an increase in the emigration of the youth population.

Although this overview contains sharp differences by region and social class, it gives us an idea of the importance migrations have had and continue to have in Argentina. According to census data, the foreign population has continuously decreased in every census since 1914, until it reached 4.2 percent in the last census in 2001. This is a result of the interruption of the European flow-despite the slight upturn observed in the post-war period, its ageing and death. The contribution of foreigners from border countries—Paraguayans, Bolivians, Chileans, and Uruguayans—has been stable as regards its percentage of the total population,2 yet failed to offset the loss of the European influx. Thus, in 2001, it accounted for 60 percent of the total foreign population.

As regards Argentinean emigration, although in the early 1960s, the flow appeared to be related to the country's political ups and downs—successive corps—and could be regarded as a merely conjunctural phenomenon, nowadays, Argentineans' movements aboard appear to have acquired a structural nature (Novick, 2007).

Interpretative Framework

For some time now, I have been interested in exploring the political-social and ideological aspects of population phenomena and over the years, I have been able to appreciate the fertility of this field of study. However, working on texts, including legal ones, does not constitute an obvious or innocent practice. Discourse analysis experiences great difficulty in mastering its subject, since a discourse is not an obvious reality but rather the result of a construction (Mengueneau, 1980). Language and its use are neither neutral nor transparent nor indifferent to the place in which they are performed. Political texts, within which norms are contained, not only help construct social reality but also "provide social actors with interpretative models for understanding this social reality, examining the possibility of modifying it and therefore, guiding their own actions" (Vasilachis, 1997).

Policies are intimately related to law, since they are partly crystallized through the legal system. Critical theory refers to the dual aspect of law, as a specific social practice and as a discourse of power. Ideology is therefore regarded as a condition for the necessary production of legal discourse (Ruiz, 1991; Cárcova, 1991). Since Marxism, law has been understood as an instrument of domination (Poulantzas, 1969). Conversely, the alternative theory of law holds that the legal system is a partially incoherent, relatively autonomous and paradoxically contradictory system, and that using its contradictions serves to create an emancipating practice (López, Saavedra, and Ibáñez, 1978; Barcellona, and Cotturri, 1976; Tygar, and Levy, 1981). As part of law, legislation constitutes a suitable object of study for understanding social relations and the changes produced in society. The study of legal guidelines therefore serves as an appropriate means of answering certain questions: What is social conflict? Who strives to resolve it? How do they manage to do so?

Sassen (2001) holds that although construction of an international world order entails the denationalization of national policies, the international migratory process proves to be a conflictive area in which states renationalize their policies, hanging on to their right to control borders. There is a tension in the state between its authority to control foreigners' entry into the country and its obligation to protect those in its territory. Indeed, as part of population policies, external migratory policies constitute proposals and goals drawn up by the state apparatus to influence the size, composition, origin, direction, settlement, and integration of spontaneous migratory flows or as a global part of the economic-social planning drawn up (Mármora, 2002). Like the latter, the former fail to escape the complexity of the issues, not only because of the many different factors that intervene in the shaping of the migratory phenomenon (social, geopolitical, work, cultural, economic, religious, ethical, racial, ecological, political, psychological, and legal) but also because of the various public organizations that tend to become involved in these policies, as well as the interests of ethnic, business, and media groups at stake. Several studies have shown that the effects of policies—as regards the volume, direction and nature of international migration—do not always occur in the direction intended by civil servants and politicians (Teitelbaum, 1984; Zolberg, Suhrke, and Aguayo, 1986). And while some adopt a skeptical position regarding states' capacity to control migration (Hollified, 2000), others suggest that their policies have been largely successful (Brochmann, and Hammar, 1999; Strikwerda, 1999).

Policies and Strategies Prior to the 2001 Crisis

This study involved analyzing the link between public policies,3 migratory policies, development strategies and political processes as presented in the normative sphere—laws—of the state, by exploring the treatment the various governments give migratory issues (Novick, 1992, 2000, 2004).

From the Founding Era to the 1976 Coup d'État

a) During the agro-export era (1870-1930),4 a migratory policy was formulated that was associated with a major phenomenon: mass European migration. The open door policy was established during the emblematic Avellaneda Law (1876) which used various financial incentives—fare payment, accommodation, etc.—to encourage the influx of European farmers. This defined what an immigrant was for the first time, specifying the rights and obligations involved in this status. At the normative level, two images of foreigners coexisted during this period: the civilizing and the subversive. The Law of Foreigners' Residence (HCNA, 1902) may be regarded as the first regulation to legitimize discretional action by the authorities. The Law of Social Defense (HCNA, 1910) was distinctly repressive towards the migrant population in general. In relation to its control function, since the flow was largely transoceanic, the port of Buenos Aires became the only point in which the state could easily intervene. The state formulated its policy through the Ministry of the Interior and subsequently the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Private settlement companies were hired by the state to implement its ambitious migratory plan. Contradictions arose between the liberal ideology underlying the strategy used—including the ruling elite's idealization of immigrants as "civilizing agents", and the non-conformist ideology—socialist, anarchist, etc., that they brought with them. The influence of the international sphere was crucial, since not only did immigration insert Argentina into the world market, it also made it visible, in parliamentary debates, through "external creditors", who had to be taken into account when it came to determining public spending to pay for the promotion of European immigration.

b) Industrializing Import Substitute Strategy. Conservative Governments (1930-1945).5 A number of phenomena can be observed during this period: the decline of the European migratory flow and the increase in internal migration. A restrictive policy was drawn up—designed as temporary solution to the crisis—associated with the selection of immigrants and ignoring the liberal influx regime proposed by the Avellaneda Law. However, the crisis did not affect the ideology that associated European immigration with national progress that was still deeply rooted in Argentinean society. The reduction of the flow appears to be more the result of the new international economic situation than the change in the law. State control expanded, becoming interventionist in nature. The Ministry of Agriculture would be the space responsible for formulating the policy. The influence of the international context in economic policies increased the "denationalization" due to the global economic crisis, while the migratory policy was "renationalized", in an attempt to protect the internal market affected by high unemployment rates.

c) Industrializing Import Substitute Strategy. Perón Governments (1946-1955).6 The planning experience of the period (First and Second Five-Year Plan) undertook diagnoses of the demographic problems in an attempt to act on all the phenomena. The population variable was therefore regarded as a key element in achieving the political project. The National Constitution, sanctioned by Peronism, in force from 1949 to 1956, contained explicit references to certain demographic phenomena. On the subject of migrations: it encouraged European immigration and stipulated that all those that entered the country without violating the laws enjoyed Argentineans' civil rights as well as political rights five years after having obtained citizenship. The new policy was driven by selection and guidance criteria. The idea of Latin American integration constituted one of the arguments legitimizing the amnesty policies begun by Peronist governments. The capacity for state control increased, with the Ministry of the Interior intervening, followed by the Ministry of Technical Affairs and subsequently the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. For its part, economic policy was "nationalized" in an attempt to achieve a model of autonomous capitalism. Conversely, migratory policy acknowledged the regional contribution of border countries, in which the national factor became less important as the sole model of legitimacy.

d) Industrializing Import Substitute Strategy. Concentrating Stage. Military Governments (1955-1962 and 1966-1973).7 This period is characterized by a profound crisis and a growing climate of social protest. The guidelines drawn up perceive immigrants as dangerous actors for society, increasing the violence against foreigners and authorizing the state to expel them. The reduction and fluctuation of the flow from the border countries observed during this stage is the result of various circumstances: the restrictive policy implemented, salary reductions, economic recession, and the exclusion and repression of undocumented migrants. The policy was "renationalized" since it only defined national interests "threatened" by foreigners, while the dominant liberal ideology proved influential in redefining economic policies by encouraging new and growing foreign capital investment.

e) Industrializing Strategy (1963-1966 and 1973-1976). Distributive Stage. Democratic Governments.8 This period is characterized by a generous policy towards Latin American immigrants (two amnesties), a progressive position in the international sphere (World Population Conference in Bucharest, 1974), where the migratory phenomenon was regarded as a factor of progress and development, and the creation of new institutional spheres. Peronism's planning experience (Three-Year Plan for National Reconstruction and Liberation, 1973) formulated four basic projects: a) orientation of internal migrations; b) recovery of Argentinean emigration to other countries; c) integration of Latin American immigration; and

d) promotion of overseas immigration. Migratory policy took the regional context into account again and was denationalized whereas economic policies attempted to recovery sovereignty to protect national interests.

From 1976 Coup d'Etat to 2001 Crisis

The strategy of economic openness and liberalization includes several stages. The first, involving initiation and penetration (1976-1983), carried out by the military government, was the most energetic and bloodiest. The second, entailing transition (1984-1989), took place during Dr. Raúl Alfonsín's government, when certain sectors still resisted deregulation and created a certain impasse. The third period (1989-1999) was one of consolidation during the governments of Dr. Carlos Menem, when there were no socially organized groups able to oppose the neoliberal project implemented. The fourth was one of collapse, during Dr. De la Rúa's government, when the failure of the model, the financial crisis and social protest led to the president's resignation.

a) In relation to the population issue, particularly the migratory issues, the dictatorship quickly showed interest in these issues. In 1977, government passed a decree establishing the National Population Objectives and Policies. In 1981, a law was passed replacing all current legislation: the General Law of Migration and the Promotion of Immigration (HCNA, 1981) comprising 115 articles, revoked the Avellaneda Law. Its considerations argued the need to encourage immigration, which it expressly declared should be European, associating it with the colonizing process, to consolidate and increase the country's population assets. The law expressly forbade all undocumented foreigners from engaging in paid activities, denying them access to health and education services and obliging civil servants to denounce the situation to the authorities. The "national security doctrine" continued to underlie military regulations. The Ministry of the Interior would be the exclusive sphere for policy design, while its ability to control became increasingly concentrated and discretional. The migratory phenomenon was regulated from an almost exclusively police-based perspective. Migratory policy was nationalized, while economic policy was denationalized by encouraging the influx of foreign capitals, guaranteeing their profitability and transferring it to state firms.

b) Contradictory policies were observed during Dr. Alfonsín's government: although an amnesty was decreed in 1984, permitting the integration of immigrants, in 1985, a restrictive immigration policy was formulated through a minor regulation (Ruling 2340/1985 of the National Migration Department).9 Two years later, a decree was passed whereby the migration law in force during the military dictatorship was regulated, lending it legal and ideological validity. As for emigration, in 1984, a policy designed to ensure the return of Argentinean exiles was passed. In short, its decisions show an ambivalent position, which failed to meet the expectations raised by the advent of democracy. Economic policy was not substantially modified, maintaining the project of trade liberalization. Conversely restrictive migratory policy was extended, legitimizing the traditional state spaces involved.

c) A contradictory policy continued during Dr. Menem's governments. Regarding emigration, in 1991, a law was passed allowed Argentineans resident abroad to vote, once they had been registered in the Electoral Roll. The first time this law was enforced was during the legislative elections of 1993. A total of 8 823 Argentineans had registered, 62 percent of whom voted, since the law stipulated a voluntary right (HCNA, 1991). Regarding immigration, certain integrating experiences were observed: such as the law, passed in 1992, granting amnesty to citizens from border countries as well as the signing of Migratory Agreements with Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay in 1998. The three bilateral instruments expressly acknowledged the shared responsibility of the three countries of origin and destination, and their importance lay in the fact that they facilitated the legalization of immigrant workers. Another advance observed during this period involved granting foreigners the right to vote in municipal and/or provincial elections.10 Paradoxically, this period also saw the emergence and expansion of restrictive trends. Thus, in 1993, the president sanctioned a decree authorizing the National Migration Department (NMD), with the support of security forces, to conduct national supervision operations throughout the country to verify immigrants' legal status. Attempts were made to justify the legitimacy of this harsh measure on the basis of the severe problem caused "by the illegal occupancy of housing and other crimes affecting social peace". This decree heralded the new restrictive policy that would subsequently be sanctioned (PEN, 1994). The following year, new admission criteria were established "to protect national interests" and the regulation passed by Alfonsín was repealed. A comparative interpretation of the two regulations—Alfonsín's and Menem's decrees—, one radical, the other legalistic, clearly reveals greater control and concentration of decision making in the Ministry of the Interior. In 1998, a regulation was passed, introducing regressive changes into immigrants' rights. Demanding a written work contract as an essential condition for legally engaging in lucrative activities— when half the Argentinean work force is employed in the underground economy—reflects its restrictive spirit (PEN, 1998).

Regarding social actors, it is interesting to note the creation of two Population Commissions in Parliament, giving it greater scope to formulate policies. In the constitutional reform of 1994, the migratory issue did not undergo any modifications, and merely repeated ideas that had been in force since 1853. Once the neoliberal model was intensified and openness to the globalized world was imposed, economic policies were "denationalized". The migratory policy tended to resolve internal tensions, accusing immigrants from the border countries of being responsible for the failure of the model and exacerbating xenophobic views. At the same time, the rights of citizens in its deterritorialized population were expanded, by incorporating them into the re-writing of its national imaginaries as a means of positioning itself in the world economic system.

d) The government of Dr. Fernando de la Rúa came to power in 1999 and attempted to improve the most controversial aspects of the previous administration: by adopting the neoliberal perspective, it sought to do away with corruption. However, as a result of the expansion of the economic crisis and growing foreign debt, social protest increased to such an extent that in December 2001, the president was forced to resign. This period was characterized by: high unemployment rates, a shortage of state resources for social policies, greater dependence on international financial centers, a regression of state participation in vital areas of society, an increase in poverty and so on. The unemployed, now known as piqueteros, became more active in their mobilizations, demanding their rights. It is significant that this democratic government failed to sanction any amnesty decrees, as had been done since the middle of the century.

Policies and Strategies Following the 2001 Crisis

The 2001 crisis proved to be a point of inflection in Argentinean history, since it destroyed the dominant bloc, putting an end to the pattern of accumulation that had prevailed for the previous thirty years. Other contributing factors included social mobilization and the leading role of the popular sectors in the collapse of the neoliberal model. Two options were proposed as a solution to the crisis: dollarization, proposed by foreign firms and transnational banking, and devaluation, proposed by the diversified oligarchy (economic groups together with a number of foreign conglomerates). This last option prevailed, with catastrophic effects for the most vulnerable sectors (Basualdo, 2006). This problematic context gave rise to the government of Néstor Kirchner, through free elections won by a narrow margin. Thus, a transformed Latin American political scenario marked the start of economic growth that reduced the high levels of unemployment caused by the neoliberal government. As for the migratory issue, the law sanctioned by the military in 1981 had already been operating for 20 years and was not easy to repeal. Dr. Menem's government saw numerous bills on migrations, yet results regarding the repeal of military law were negligible. Some of the projects only proposed partial reforms (a total of six were submitted between 1996 and 1999) while others sought to repeal it (a total of four were submitted between 1994 and 1999). The unified project, agreed on in December 1999 at the Commission of Population and Human Rights of the Chamber of Deputies, served as the basis for Rep. Giustiniani (Socialist Party) to draft his bill, submitted to Congress in December 2001 and again in March 2003. Following several parliamentary ups and downs, and in view of the possibility of further delay, it was agreed to deal with the bill during the last ordinary session of the Chamber of Deputies in 2003, where it was unanimously approved by the delegates. A few days later, in December, law num. 25.871 was passed in the Senate. A reading of the General Principles of the new law shows that it points towards formulating a new national demographic policy, by strengthening the country's socio-cultural fabric, and promoting immigrants' integration into society and the labor force. One of the most important reforms undertaken by the law is the recognition of the human right to migrate. According to article 4, "The right to migration is the essential, inalienable right of a person, which the Argentinean Republic guarantees on the basis of the principles of equality and universality". This article not only acknowledges and incorporates into internal law what is established in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights but stipulates the state's obligation to guarantee this right. A summary of the new rights enshrined in the law num. 25.871 is given below:

It also introduces the principle of effective legal control of all the administrative documents issued by the respective authorities. In the event of expulsion, the immigrant may utilize administrative and judicial resources. The decision to expel him will therefore only be determined by a judge.

At the same time, article 17 reverses the criterion usually associated with the influx of foreigners. Whereas in military legislation, emphasis was placed on the police control of undocumented immigrants, who were forced into irregularity by the difficulty of completing their paperwork, the new law encouraged them to legalize their status.

In relation to Mercosur, the new law cites, for the first time ever in the history of migratory legislation, a process of regional integration and gives citizens of member countries special treatment.

This new Mercosur perspective is confirmed in the amnesty decree drawn up by the president, granting foreigners from outside Mercosur resident in Argentina on June 30, 2004 the possibility of legalizing their migratory status within a period of 180 days. Expulsions were suspended for foreigners who were able to take advantage of the benefits afforded by this decree. The new migratory law was cited as the legal basis in the sense that the state must provide the conditions to enable foreigners to legalize their situation.

Table 2, given below, shows that 12 065 persons took advantage of the benefits of this amnesty. The majority were from Asia, followed by Latin Americans. The largest group comprised persons from China, followed by Koreans, and then Colombians and Dominicans.

The NMD subsequently created the National Program of Normalization of Migratory Documents, designed to: a) legalize immigrants' status, and b) create new policies to ensure the insertion and integration of the immigrant population (PEN, 2004a).

In June 2005, a new decree extended the NMD's administrative emergency and arranged for the migratory legalization of foreigners from Mercosur and associated countries (PEN, 2005). This process, implemented from April 2006 onwards and known as Patria Grande program, enabled persons from countries in the expanded Mercosur (Uruguay, Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, Chile, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama) to obtain a temporary, two-year stay in the country through simplified requirements. After this period had elapsed, people could choose to request permanent residence in Argentina provided they were able to prove "a legal livelihood".

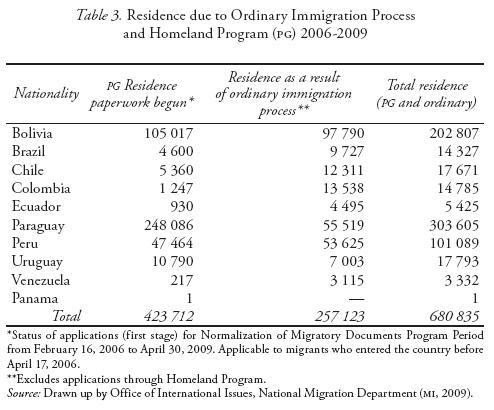

As one can see from table 3, between April 17, 2006 and April 30, 2009, through the Homeland Program, 423 712 immigrants have gained access to legal residence. As one can see, Paraguayan citizens are the largest group, followed by Bolivians and Peruvians (first column).

At the same time, the new law establishes preferential treatment—by nationality—for immigrants from countries in the expanded Mercosur countries, by providing them with temporary residence with authorization to remain in the country for two years, which may be extended, with multiple entrances and exits. The number of immigrants who settled in Argentina as a result of this program totals 257 123. The most numerous group are Bolivians, followed by Paraguayans and Peruvians (second column).

Lastly, the combination of the two processes, from 2006 to 2009, gives a total of 680 835 legalized immigrants. Paraguayans comprise the largest group, followed by Bolivians and Peruvians (third column).

These figures show that there a significant amount of immigrants from border countries living in extremely vulnerable conditions. They lack formal legal status that would include them and enable them to engage in various activities, whether social, political or cultural. Moreover, the flow from neighboring countries has not stopped despite the crisis and Argentina is still a focus of attraction in the southern region.

Unlike the amnesty decrees issued in Argentina since 1949 by all the democratic governments, this program proposes the permanent legalization of immigrants. It is a plan drawn up by government with the collaboration, for the first time ever in this type of applications, of municipal organizations, immigrants', religious, trade union, and civil society associations. The government emphasizes the success of the initiatives and holds it up as a model in Latin America. For our part, we believe that the program constitutes a step forward, despite the obstacles it has faced in its everyday practice.

Taking up the thread of our research, we could add that the new Argentinean migratory policy is being "denationalized" through new visions: the acceptance and reception of the principle established by international guidelines regarding the right to migrate as an essential human right, a circumstance that limits the autonomy and power of the state. In addition, it prioritizes the process of regional integration as an important factor in granting differentiated rights, by expanding the scenario and defining policy through criteria that exceed strictly national limits. At the same time, in the economic sphere, greater concern can be observed over nationalizing the policy to limit the bonds of dependence on international financing organizations.

Nevertheless, there is an ambiguous panorama regarding the spaces involved. One of the issues is the tension between the Ministry of the Interior and Foreign Affairs in the formulation and enforcement of the policy, particularly as regards émigrés. This tension reflects the vision of each of these spaces and their traditional perspectives. It suggests that through the sanction of the new law, the balance has tipped towards the Ministry of the Interior. For the first time ever, the law includes emigration issues. Since the NMD, which belongs to this ministry, is responsible for enforcing this law, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has to some extent been affected in an area that was previously its exclusive province.

Mercosur Agreements

The maturity of the regional integration process was partly responsible for the fact that in 2002, the four Mercosur countries and Bolivia, and Chile signed an agreement on the permanent legalization of nations, designed to "facilitate migratory applications through legal instruments" by permitting their legalization without the need for them to return to their countries of origin (Mercosur, 2002).

A few months later, on December 6, 2002, an agreement on residence for nationals of the party states to the expanded Mercosur was signed. This instrument was passed by Argentina on June 9, 2004 through Law 25.902. The agreement affirmed, "The desire of the Mercosur party states and member to strengthen and deepen the process of integration as well as the fraternal links between them". It stated that, "The implementation of a policy to ensure the free circulation of persons in the region is essential to achieving these aims". It also seeks, "To resolve the migratory status of the nationals of the party states and members in the region in order to strengthen the links binding the regional community". The agreement seeks to establish common rules for applying for residence for the nationals of the various countries mentioned. Citizens of a party state resident in their own country or living in another state may request temporary residence for two years, provided they fulfill certain requirements (valid passport, birth certificate, certificate accrediting the lack of a criminal record, medical certificate, and payment of a fee). Temporary residence may become permanent provided the applicant submits an application to the migratory authorities in the receiving country within the ninety days prior to the expiration of his or her temporary residence permit.

The agreement goes beyond the free circulation of goods and begins to contemplate the free circulation of persons, as well as expanding the concept of human rights. An attempt is being made to simplify paperwork to encourage an exchange between countries in order to create a genuine community, by facilitating entry and guaranteeing migrants' fundamental rights from one country to another. In addition to civil liberties—the right to come and go, the right to work, the right of association, and the right to worship—it also contains the right to family reunification and the transfer of resources. In the case of workers' rights, the Agreement clearly stipulates equality in the application of labor rights, in addition to the commitments acquired in reciprocal agreements legislation regarding pensions. Immigrants' children will also enjoy identical opportunities regarding education. The same guarantees a state awards its citizens should be extended to any citizen belonging to the Mercosur countries inhabiting its country. Article 11 includes a criterion for general interpretation: in the event of doubt, the regulation that is most favorable to the immigrant will be applied. On May 20, 2004, the Brazilian Congress passed this historic agreement. Lastly, the agreement came into effect in August 2008, since it was approved by Argentina, Brazil and Bolivia in 2004. It was subsequently approved by Uruguay and Chile in 2005, and lastly by Paraguay in 2008. Despite the obstacles that may still occur regarding its application, this novel, transcendental fact marks the start of the regional construction of a migratory policy.

R@ICES Program

In October 2003, within the sphere of the Ministry of Education, a program called r@ices (Red de Argentinos Investigadores y Científicos en el Exterior/Network of Argentinean Researchers and Scientists Abroad) was designed to promote liaison policies with Argentinean researchers abroad, as well as actions to encourage their permanence in the country and the return of those interested in performing their activities in Argentina. In November 2008, through Law 26421 (HCNA, 2008), this program acquired the status of a state policy, now under the auspices of the recently-created Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation. Since its inception, approximately 780 researchers, mainly from the exact sciences, have been repatriated through the Return Subsidies and Reinsertion Scholarships of the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (Conicet). France, the United States and Great Britain are the main countries from which they returned, followed, in order of importance, by Italy, Germany and Canada.

New Refugee Law

For some time, the United Nations High Comissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and NGOS engaged in the protection of immigrants and refugees had requested the passage of a refugee law. They pointed to the need for a clear, concrete normative framework that would provide legal status for refugees and applicants. The sanction of the new General Law of Recognition and Protection of Refugees num. 26165 (HCNA, 2006a), passed by the National Congress on November 8, 2006, clearly legislates on behalf of refuge, based on international human rights law. It also created the National Refugee Commission, an organization responsible for enforcing the law, within the Ministry of the Interior. It is interesting to note that although this institution will comprise five members belonging to national government, it will also include one member of UNHCR and another member of refugee associations and NGOS. Here, as in the implementation of the Patria Grande program, the policy incorporates social actors from civil society, who partly circumscribe state power.

International Convention

The passage, in December 2006, through the Law 26202 (HCNA, 2006b), of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of all Migrant Workers and Members of their Families11 (UNGA, 1990) constituted an important event for Argentina. It marked the end of a lengthy process in which the Argentinean state sought ideological coherence with the establishment of the right to migrate as an essential human right. As for the international scope of the convention, it should be pointed out that it has been ratified by 57 countries although the central countries, which receive immigrants, have yet to do so. In Latin America, it has been ratified by 15 countries. These circumstances have transformed this part of the American continent into an area where rights are protected. The most significant countries to sign are Chile and Argentina, since they are still receiving countries.

Initiatives by the Ministry of the Interior

On March 12, 2007, as a result of Ruling 452 (MI, 2007), the Ministry of the Interior created an ambitious program called Province 25, run by the Secretariat of Provinces, to strengthen the links and communication between the state and Argentineans resident abroad by "assisting them with everything related to the exercise of their political rights, the creation of sphere of sectoral political representation, and the optimization of paperwork and applications". The regulation bases its legitimacy on the increase of the flow which, according to estimates from the NMD, amounts to 1 053 000 persons, "a much higher figure than the number of those on the electoral roll of several Argentinean provinces". However, the evolution of the electoral participation of Argentinean émigrés has been scarce and is on the decline, as shown by the following chart:

The ruling states that the system in force entails high operating costs for the state, and delays in vote counting as well as involving a significant effort for voters. This raises the need to create a political institution that will represent them and reflect their interests.

In keeping with this perspective, in August 2009, a bill on the "Creation of an Overseas District and Parliamentary Representation" was submitted to the Chamber of Deputies. The bill proposed that Argentinean citizens resident abroad should be entitled to elect five delegates to represent them in the Chamber of Deputies. Political parties with legal status as a national party can propose candidates for the Overseas District. Argentineans will not only be able to vote in the elections but also be able to be represented in Parliament. The bases of the project cite European (France, Italy, and Switzerland) and Latin American (Colombia and Ecuador) legislations as positive experiences. The bill has been submitted for approval by the Commissions for Constitutional Affairs, Foreign Affairs and Worship. We regard this as a positive extension of the recognition of political rights, which intensified the process of deterritorialization.

Final Notes

The new migratory law sanctioned by the National Congress in December 2003 marks a substantial change in Argentinean migratory policy as well as constituting a historic achievement: repealing a law dating from the era of the military dictatorship after twenty years of democratic governments. The social model underlying the new law reflects the idea of a more egalitarian society that values the potential of youth and immigrants' contribution. Society appears to be immersed in a regional process, Mercosur, whose growing importance influenced the definition of new policies.

Several circumstances reveal an ideological twist at the formal level of recent policy: a) passage of the International Convention, which protects the rights of migrant workers and their relatives; b) the new refugee law, covering a legal gap that the organizations and associations involved have long asked to be filled; c) amnesty for immigrants outside Mercosur; d) the implementation of the Patria Grande program for permanente regularization; e) the approval of the Law on Residence in Mercosur; f) the expansion of immigrants' and refugees' participation in the new legislation; g) the expansion of citizens' rights outside national territory; h) the discourse of government officials responsible for migratory policy. These references indicate the acceptance of the principles in force in the international context and the transformation of the paradigm sustaining the policy: of "national security" as a value to be protected from the potential threat from foreigners by acknowledging the human right to migrate.

At the same time, politics has become more complex in many respects: a) regarding the origin of the flows: the traditional flow of immigrants from neighboring countries and Korea has now been expanded by immigrants from China; b) regarding its dual nature as a sending and receiving country that now characterizes Argentina, which implies an original perspective on the problem; c) regarding the new actors involved in the formulation and enforcement of policies: the growing participation of social sectors—civil society organizations—as well as other governments: of countries where Argentineans reside, of the immigrants' countries or countries with which a space of regional integration is being built. The state and its specialized officials are no longer the only ones responsible for this issue.

Although the recent changes have advanced regarding the protection and respect of migrants' rights, specific studies have shown that immigrants in Argentina continue to be discriminated against and exploited, and in many cases, persecuted and mistreated. There are cultural, economic, and ideological issues explaining this phenomenon. What is still under debate is the extent to which immigrants experience this treatment because they are foreign or poor.

One of the problems to be solved involved the sanction of a legal ruling, postponed for several years and only recently enacted. On May 3, 2010, Decree 616/2010 (PEN, 2010), governing the Law of Migrations num. 25871 (HCNA, 2004) was sanctioned. Likewise, the innovations are not automatically reflected in the social actors who should apply these guidelines every day. On the contrary, decades of authoritarian military ideology influence the contradictions that occur on a daily basis between the laws that have been passed and political practices. It will be a challenge for society as a whole to change the mentality of the social actors responsible for implementing the new law. The state must implement proper work training programs for NMD agents and its auxiliary police force, as well as publicity and information campaigns. The national, provincial, and municipal regulations contradicting the new law must be repealed. The third challenge is the need to persuade certain sectors of society of the advantages of the new regulation and thereby neutralize some of the bills submitted to the Chamber of Deputies that seek to amend it by restricting rights and guarantees.

Nevertheless, progress has been made in the application of the new law. This is borne out by the sentence passed by the Federal Chamber of Appeals in the city of Paraná in the Province of Entre Ríos, demanding the immediate release of three Chinese citizens who had been arrested in Concordia, during an operation carried out by personnel from the Argentinean Naval Sub-Prefecture.

The long-term perspective shows that during the agro-export strategy (1870-1930), economic policy was denationalized, opening up the economy to foreign investment in railroads, meat industry, and services as was migration policy. This led to the promotion of European immigration associated with settlement, the extermination of the indigenous population, with the participation of civil society groups—private settlement firms—together with the enforcement of the policy that had been designed. On the other hand, during the subsequent period (1930-1945) and partly as a result of the serious international crisis, whereas economic policy was denationalized—through growing American investment in the textile and food industries—migratory policy became more restrictive and was nationalized, protecting the domestic market from high unemployment rates. Conversely, during the first decade of Peronism (1945-1955), economic policy was nationalized, in an attempt to create an autonomous form of capitalism: through an increase in public investment, the nationalization of foreign firms, etc. Migratory policy was denationalized, since the Latin American context was regarded as a variable in the amnesties formulated. Conversely, the concentrating industrializing experience (1955-1962, and 1966-1973) denationalized economic policy through foreign investment and the expansion of monopolistic multinational firms, and nationalized migratory policy, through restrictions on immigrants from border countries and repressive measures against undocumented immigrants, now based on internal control and national security. The distributive experience (1963-1966 and 1973-1976) nationalized economic policy, through an increase in public investment, state control of foreign capital and denationalized migratory policy through amnesties for border migrants and the promotion of Latin Americanmigration. Following the 1976 coup d'État, economic policy was denationalized, through a process of foreign investment and rapid privatization. Migratory policy was partly nationalized through profound contradictions, which includes the growing control of undocumented migrants, restrictions on border migrants, amnesties and so on.

Finally, in the wake of the 2001 crisis, the new Argentinean migratory policy was denationalized through two factors: a) the priority given to the process of regional integration as an important factor in granting differentiated rights—for Mercosur members and non-members—by expanding the scenario and defining policy through criteria that exceed strictly national limits, and b) the acceptance of the international framework for the protection of human rights, which restricted the state's autonomy and power. At the same time, in the economic sphere, an ambiguous process was observed that attempted to recover part of national sovereignty from international financing organizations, through the refusal to pay debts, the rejection of IMF policies and so on.

During the periods of conservative, concentrating strategies, including military ones, migratory policies tended to be nationalized. Conversely, distributive experiences were characterized by a process of denationalization. Border migrations appeared on the government's agenda in the 1930s, playing a crucial role in the import substitute strategy. In principle, one could say that the evolution of this trend over time has suffered the effect of the uneven policies designed by the various governments: military policies are restrictive while those drawn up by democratic governments are reparatory. Some studies (Novick, 2000), however, show that the link between governments' ideological origin and their respective external migratory policies is neither mechanical nor univocal. In Argentina, the ideological dimension that influences migratory policy design cuts through and goes beyond the normative-political perspective, revealing a degree of autonomy that appears to be more closely linked to our cultural history. For its part, the international sphere is present throughout the period studied, although it has acquired different shades and intensities.

In relation to the Latin American region, the 1990s saw the beginning of a bi- and multilateral treatment of migrations that went beyond the traditional perspective of regarding policy of an instrument that is merely related to national sovereignty (borders, security, etc.). The bilateral agreements signed with Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay in the late 1990s were forerunners to the policy formulated after the 2001 crisis.

Sassen (2001) holds that although construction of an international world order entails the denationalization of national policies, the international migratory process proves to be a conflictive area in which states renationalize their policies, hanging on to their right to control borders. But here we must distinguish between central and peripheral countries. In fact, the Argentinean case is paradigmatic, since whereas other receiving countries emphasize restrictive policies and in some cases ignore human rights principles, such as the Return Guidelines in the European Union and the California Law in the United States, the experience in Argentina, still a magnet for Latin American migrants, after a profound economic and social crisis, has been quite the opposite.

References

Argentinean Congress (HCNA), 1902, "Estableciendo los casos en que podrá ordenarse la salida del territorio a extranjeros" [law 4144], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 2751, Buenos Aires, p. 1, November 25. Available at <http://www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/BuscadoresPrimeraLog/BusquedaAvanzadaLogDetalle.castle?dest=&idAviso=7004373> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Argentinean Congress (HCNA), 1910, "Ley de defensa social" [law 7029], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, Buenos Aires, p. 1, July 8. Available at <http://www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/BuscadoresPrimeraLog/BusquedaAvanzadaLogDetalle.castle?dest=&idAviso=7006913> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Argentinean Congress (HCNA), 1981, "Ley general de migraciones y fomento de la inmigración" [law 22439], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 24637, Buenos Aires, March 27, p. 1. Available at <http://www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/BuscadoresPrimeraLog/BusquedaAvanzadaLogDetalle.castle?dest=&idAviso=7083550> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Argentinean Congress (HCNA), 1991, "Créase el registro de electores residentes en el exterior" [law 24007], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 27256, Buenos Aires, November 5, p. 1. Available at <http://www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/BuscadoresPrimeraLog/BusquedaAvanzadaLogDetalle.castle?dest=&idAviso=7125413> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Argentinean Congress (HCNA), 2004, "Política migratoria argentina. Derechos y obligaciones de los extranjeros" [law 25871], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 30322, Buenos Aires, January 21, p. 2. Available at <http://www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/BuscadoresPrimeraLog/BusquedaAvanzadaLogDetalle.castle?dest=&idAviso=7259562> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Argentinean Congress (HCNA), 2006a, "Ley general de reconocimiento y protección al refugiado" [law 26165], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 31045, Buenos Aires, November 28, pp. 1-5. Available at <http://www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/BuscadoresPrimeraLog/BusquedaAvanzadaLogDetalle.castle?dest=&idAviso=9092584> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Argentinean Congress (HCNA), 2006b, "Apruébase la Convención Internacional sobre la Protección de todos los Trabaja dores Migratorios y de sus Familiares, adoptada por la Organización de las Naciones Unidas, el 18 de diciembre de 1990" [law 26202], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 31075, Buenos Aires, December 13, pp. 6-12. Available at <http://www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/BuscadoresPrimeraLog/BusquedaAvanzadaLogDetalle.castle?dest=&idAviso=9114567> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Argentinean Congress (HCNA), 2008, "Establécese que el Pro-grama Red de Argentinos Investigadores y Científicos en el Exterior (r@ices), creado en el ámbito del Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Productiva, será asumido como política de Estado" [law 26421], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 31532, Buenos Aires, November 14, pp. 1-2. Available at <http://www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/BuscadoresPrimeraLog/BusquedaAvanzadaLogDetalle.castle?dest=&idAviso=9282381> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Barcellona P., and G. Cotturri, 1976, El Estado y los juristas, Barcelona, Fontanella. [ Links ]

Basualdo, E. M., 2006, Estudios de historia económica argentina de mediados del siglo a la actualidad, Buenos Aires, Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Brochmann, G., and T. Hammar, eds., 1999, Mechanisms of Immigration Control, Oxford, New York, Berg. [ Links ]

Cárcova, Carlos M., 1991, "Acerca de las funciones del derecho", in Enrique Marí et al., Materiales para una teoría crítica del derecho, Buenos Aires, Abeledo Perrot. [ Links ]

Correa, G., 1975, "Estrategias de desarrollo, poder y población. Notas tentativas para el análisis de sus relaciones", in Raúl Atria, ed., Estructura política y políticas de población, Santiago, Chile, Pispal-Flacso. [ Links ]

De la Fuente, Diego G;, Gabriel Carrasco, and Alberto B. Martínez, 1898, Segundo censo de la República Argentina, Bue nos Aires, Taller Tipográfico de la Penitenciaria Nacional, three vols. [ Links ]

Hollifield, J. F., 2000, "The Politics of International Migration: How Can We 'Bring the State Back in'?", in C. B. Brettell and J. F. Hollifield, eds., Migration Theory: Talking across Disciplines, New York/London, Routledge. [ Links ]

López Calera, Nicolás; Modesto Saavedra López, and Perfecto Ibáñez, 1978, Sobre el uso alternativo del derecho, Valencia, Fernando Torres. [ Links ]

Mármora, Lelio, 2002, Las políticas de migraciones internacionales, Buenos Aires, Paidós. [ Links ]

Martínez, Alberto B., 1916, Tercer censo nacional 1914, Buenos Aires, Talleres Gráficos de L. J. Rosso, 10 vols. [ Links ]

Mazzeo, V. [paper], 1993, "Dinámica demográfica de Argentina en el período 1947-1991. Análisis de sus componentes y diferenciales", on "2nd Argentinean Population Study Days", Buenos Aires, August 4-6. [ Links ]

Mengueneau, D., 1980, Introducción a los métodos de análisis del análisis del discurso, Buenos Aires, Hachette. [ Links ]

Mercosur, 2002, "Acuerdo sobre regularización migratoria interna de ciudadanos del Mercosur", Brasilia, December 5. Available at <http://www.fundacionalende.org.ar/archivos/migrantes/Acuerdo%20Regularizaci%F3n%20Migratoria%20Interna%20MSUR.pdf> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Ministry of the Interior (MI), 1872, Primer censo de la República Argentina 1869, Buenos Aires, Office of National Statistics/ Imprenta del Porvenir. [ Links ]

Ministry of the Interior (MI) [personal correspondence], 2005, Buenos Aires, Office of International Issues-National Migration Department, October 13. [ Links ]

Ministry of the Interior (MI), 2007, "Créase el programa Provincia 25, con el objeto de fortalecer los vínculos y la comunicación del Estado argentino con los argentinos residentes en el exterior" [legal ruling 452/2007], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 31117, Buenos Aires, March 16, p. 14. Available at <http://www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/DisplayPdf.aspx?s=BPBCF&f=20070316> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Ministry of the Interior (MI) [personal correspondence], 2009, Buenos Aires, Office of International Issues-National Migration Department, September, 29. [ Links ]

National Executive Office (PEN), 1962, Censo nacional de población, viviendas y agropecuario 1960, Buenos Aires, Secretariat of Finance, National Statistics and Census Department, four vols. [ Links ]

National Executive Office (PEN), 1994, "Establécense operativos de control de la situación legal de inmigrantes" [decree 2771/ 93], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 27802, Infoleg, Buenos Aires, CDI Ministry of Economy, p. 17, January 6. Available at <http://infoleg.mecon.gov.ar/infolegInternet/verNorma.do?id=9435> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

National Executive Office (PEN), 1998, "Apruébase el Reglamento de Migración" [decree 1117/98], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 28995, Infoleg, Buenos Aires, CDI Ministry of Economy, October 6, p. 2. Available at <http://infoleg.mecon.gov.ar/infolegInternet/verNorma.do?id=53426> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

National Executive Office (PEN), 2004a, "Declárase la emergencia administrativa del citado organismo descentralizado de la órbita del Ministerio del Interior" [decree 836/2004], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 30438, Infoleg, Buenos Aires, CDI Ministry of Economy, July 8, p. 4. Available at <http://www.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/verNorma.do?id=96402> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

National Executive Office (PEN), 2004b, "Regularización de la situación migratoria de ciudadanos nativos de países fuera de la órbita del Mercosur, que al 30 de junio de 2004 residan de hecho en el territorio nacional" [decree 1169/2004], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 30483, Infoleg, Buenos Aires, CDI Ministry of Economy, September 13, p. 1. Available at <http://www.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/verNorma.do?id=98547> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

National Executive Office (PEN), 2005, "Dase por prorrogada la emergencia administrativa de la citada dirección nacional, organismo descentralizado actuante en la órbita del Ministerio del Interior" [decree 578/2005], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 30668, Infoleg, Buenos Aires, CDI Ministry of Economy, June 6, p. 1. Available at <http://www.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/verNorma.do?id=106817> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

National Executive Office (PEN), 2010, "Reglamentación de la Ley de Migraciones Nº 25871 y sus modificatorias" [decree 616/2010], Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, num. 31898, Infoleg, Buenos Aires, CDI Ministry of Economy, May 6, p. 6. Available at <http://www.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/verNorma.do?id=167004> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC), 1977, Censo general de población, familias y viviendas 1970, Buenos Aires, INDEC. [ Links ]

National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC), 1994, Censo nacional de población y vivienda 1991. Resultados definitivos [series C, part 2], Buenos Aires, INDEC. [ Links ]

National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) [cd-rom], 2001, Censo nacional de población, hogares y viviendas 2001. Resultados generales. Total del país [series 2, num. 25], Buenos Aires, Ministry of Economy/Secretariat of Economic Policy/ INDEC. [ Links ]

Novick. S., 1992, Política y población. Argentina 1870-1989, Buenos Aires, CEAL, two vols. [ Links ]

Novick, S., 2000, "Política migratoria en la Argentina", in E. Oteiza, S. Novick and R. Aruj, eds., Inmigración y discriminación. Políticas y discursos, 2nd ed., Buenos Aires, Trama Editorial/Prometeo Libros, May. [ Links ]

Novick, S., 2004, "Una nueva ley para un nuevo modelo de desarrollo en un contexto de crisis y consenso", in Rubén Giustiniani, ed., La migración: Un derecho humano, Buenos Aires, Prometeo. [ Links ]

Novick, S., 2007, "Políticas y actores sociales frente a la emigración de argentinos", Sur-norte. Estudios sobre la emigración reciente de argentinos, Buenos Aires, Catálogos-Universidad de Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Poulantzas, Nicos, 1969, Hegemonía y dominación en el Estado moderno, Córdoba, Argentina, Ediciones Pasado y Presente. [ Links ]

President's Office, 1951, Cuarto censo general de la nación 1947, Buenos Aires, Ministry of Technical Affairs/National Statistics Office, three vols. [ Links ]

President's Office, 1981, Censo nacional de población y vivienda, 1980: Resumen nacional [series D. Población], Buenos Aires, National Executive Census Committee 1980/INDEC. [ Links ]

Ruiz, A., 1991, "Aspectos ideológicos del discurso jurídico", in Enrique Marí, et al., Materiales para una crítica del derecho, Buenos Aires, Abeledo Perrot. [ Links ]

Sassen, S., 2001, ¿Perdiendo el control? La soberanía en la era de la globalización, Barcelona, Bellaterra, pp. 73-106. [ Links ]

Strikwerda, C., 1999, "Tides of Migration, Currents of History: The State, Economy, and the Transatlantic Movement of Labor in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries", International Review of Social History, num. 44. [ Links ]

Teitelbaum, M. S., 1984, "Immigration, Refugees, and Foreign-Policy", International Organization, vol. 38, num. 3, pp. 429-450. [ Links ]

Tygar, E. M., and M. Levy, 1981, El derecho y el ascenso del capitalismo, 2nd ed., Mexico, Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), 1990, "International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families" [a/res/45/158]. Available at <http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/45/a45r158.htm> (last accessed on June 20, 2011). [ Links ]

Vasilachis de Gialdino, I., 1997, Discurso político y prensa escrita, Barcelona, Gedisa. [ Links ]

Yocelevzky, T., and R. D. Rodríguez, 1983, "Enfoques teóricos en la investigación de políticas de población en América Latina", Sociología y Política, year 1, num. 2, February (series Políticas Públicas y Desarrollo Social). [ Links ]

Zolberg, A. R., A. Suhrke, and S. Aguayo, 1986, "International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements", International Migration Review, vol. 20, num. 2. [ Links ]

1 This paper is a summary of some of the findings yielded by the UBACYT project called: "Two Dimensions of Contemporary Migratory Argentina: Mercosur Immigrants and Argentinean Émigrés. Demographic, Political, and Social Aspects". I would like to thank Gabriela Mera for her help in designing the charts.

2 According to the Argentinean National Censuses, the proportion of border country foreigners of the total population accounted for 2.4 percent in 1869, 2.9 in 1895, 2.6 in 1914, 2 in 1947, 2.3 in 1960, 2.3 in 1970, 2.7 in 1980, 2.5 in 1991, and 2.5 percent in 2001 (MI, 1872; De la Fuente, Carrasco, and Martínez, 1898; Martínez, 1916; President's Office, 1951; PEN, 1962; INDEC, 1977; President's Office, 1981; INDEC, 1994, 2001).

3 Any public policy is based on an underlying, ideologically configured model of society, that determines which policies will be most important or which ones will be chosen while others will be rejected. Every social group will propose different development strategies to impose its own model on the rest of society. These are the result of a specific societal structure of power and the functioning of a certain state political system (Correa, 1975; Yocelevzky, and Rodríguez, 1983).

4 This period began with the presidency of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (18681874) and ended with the overthrow of the second government of Hipólito Irigoyen (1928-1930), when a coup d'état was carried out by the military. This destroyed the formal constitutional order for the first time and the liberal, agro-export model collapsed.

5 It includes nationalistic conservative governments (José F. Uriburu, Agustín P. Justo, Roberto M. Ortiz, Ramón S. Castillo), and those that emerged as a result of the 1943 Revolution (Pedro P. Ramírez, and Edelmiro J. Farrell).

6 Phase comprising the first two constitutional governments of Juan Domingo Perón.

7 It includes the governments that followed the coup d'état known as the "Revolucion Libertadora" (Eduardo Lonardi, and Pedro E. Aramburu), the Constitutional government of Arturo Frondizi, and José M. Guido; and those that arose in the wake of the "Revolución Argentina" (Juan C. Onganía, Roberto M. Levingston, and Alejandro A. Lanusse).

8 It includes the governments of Arturo H. Illia and the Peronist governments (Héctor J. Cámpora, Raúl A. Lastiri, Juan Domingo Perón, and María Estela Martínez de Perón).

9 Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, en <http://www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/Inicio/Index.castle>.

10 Although foreign residents are not allowed to vote in the national elections (for president, vicepresident or legislators), during Menem's governments they were given the right to suffrage in various provinces: La Pampa (1989), Tierra del Fuego (1991), Corrientes (1993), Buenos Aires (1994), Neuquén (1994), Chubut (1994), Chaco (1995), Mendoza (1997), Salta (1997), Misiones (1999), Formosa (2003), and in the city of Buenos Aires (1996). During Alfonsín's government, this right was granted in the following provinces: Tucumán (1983), Santa Fe (1985), San Juan (1986), Jujuy (1986), San Luis (1987), Santiago del Estero (1987), Córdoba (1987), Catamarca (1988), and Río Negro (1988).

11 Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in Resolution 45/158 of December 18, 1990. The bill requesting that Argentina adopt this resolution was submitted in July 2004 by senator Rubén H. Giustiniani, belonging to the Socialist Party (Santa Fe), and radical senators Miriam B. Curletti (Chaco), and Carlos Prades (Santa Cruz).

Información sobre la autora

Susana Novick es doctora en ciencias sociales por la Universidad de Buenos Aires, abogada por la Universidad Nacional de La Plata y magíster en ciencias sociales por la Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales. Desde 1995 es cocoordinadora del Seminario Permanente de Migraciones y ha sido titular del Seminario "Inmigración/emigración. Análisis de la problemática migratoria: El Estado, las estadísticas, las políticas y su relación con los medios". Es cofundadora y coordinadora del grupo de trabajo del Clacso "Migración, cultura y políticas" (2007-2010) y vicepresidenta del Foro Universitario del Mercosur (20092011). Entre sus publicaciones destacan Migraciones y Mercosur: Una relación inconclusa (Catálogos, 2010) y Las migraciones en América Latina. Políticas, culturas y estrategias (Clacso, 2008). Actualmente se desempeña como investigadora en el Conicet-Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, perteneciente a la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad de Buenos Aires.