Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Migraciones internacionales

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0279versión impresa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.15 Tijuana ene./dic. 2024 Epub 04-Oct-2024

https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.2843

Papers

International Academic Mobility and Migrant Students at the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Argentina)

1Instituto de Humanidades-Conicet, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina, cecilia.jimenez@unc.edu.ar

2Centro de Conocimiento, Formación e Investigación en Estudios Sociales-Conicet, Universidad Nacional de Villa María; y Facultad de Filosofía y Humanidades, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina, florencia.maggi.88@gmail.com

This paper researches the inequalities in the international itineraries of entrances and exits in the university system, linking migrations with education and academic mobility. With this purpose, it is explored from a quantitative analysis of primary and secondary sources, the presence of migrant students and undergraduate and graduate exchange students at the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (UNC), and the mobilities from the same institution to various destinations in the world. Among the main findings, the identification of relatively hierarchical spaces and a selective profile of students in the mobilities that fall within the internationalization policies stand out. Meanwhile, among UNC students born abroad, a greater heterogeneity of profiles stands out. The main contribution of this article is to simultaneously analyze mobilities that are usually observed separately, allowing us to glimpse various routes of mobile students, marked by their social class origin.

Keywords: 1. migrant students; 2. higher educational system; 3. internationalization; 4. Cordoba; 5. Argentina.

En este artículo se indagan las desigualdades en los itinerarios internacionales de entradas y salidas en el sistema universitario vinculando las migraciones con la educación y las movilidades académicas. A partir de un análisis cuantitativo de fuentes primarias y secundarias, se explora la presencia de estudiantes migrantes y de intercambio de grado y posgrado en la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (UNC), así como las movilidades desde esta institución hacia diversos destinos del mundo. Entre los principales hallazgos destaca la identificación de espacios relativamente jerarquizados y un perfil selectivo de estudiantes en las movilidades que se encuadran en las políticas de internacionalización. Sobresale una mayor heterogeneidad de perfiles entre estudiantes de la UNC nacidos en el extranjero. El principal aporte del artículo es que se analizan simultáneamente movilidades que suelen observarse por separado, lo que permite vislumbrar los diversos recorridos de los estudiantes signados por el origen de la clase social.

Palabras clave: 1. estudiantes migrantes; 2. sistema educativo superior; 3. internacionalización; 4. Córdoba; 5. Argentina.

Introduction

Mobilities for reasons of study and the acquiring of higher education among migrants constitute fertile grounds for the analysis of social inequality and access to the educational system, which provides clues to understanding the dynamics of social mobility and the strategies of residence and transit through territories. This article explores the international mobility of undergraduate and graduate students at the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (UNC) (National University of Córdoba), in Argentina. On the one hand, the participation of migrant students in undergraduate studies is investigated; on the other hand, the dynamics of leaving this institution for various destinations around the world are analyzed. By linking migrations with education and mobility, different inbound and outbound itineraries from the UNC are analyzed.

As of today, the transit of undergraduate and graduate students is an angle of the social class dynamics in the current phase of global capitalism (Sassen, 2007; Wagner, 2007). One of the motivations behind these movements is to identify opportunities for future job positioning. In these mobilities, students visit prestigious academic institutions-generally located in the countries of the global north-, which has an impact on the local scientific fields of the peripheries (Kreimer, 2012). However, these dynamics also reach extra-academic spaces, such as the business world. In these terms, García Garza and Wagner (2015) analyze this dynamic in private spheres, and review the way in which Mexican elites accumulate knowledge in the great French business schools, so as to position themselves in their country.

International movements into and out of the higher education system are expressions of the social mobility strategies of families, and support the enrollment of coming young generations in said system. Furthermore, these flows involve the mobility of highly skilled personnel who are then faced with the dilemma of choosing between temporary migration (at the end of their education) and settling in the country where they have studied (to enter the labor market).

At the same time, these mobilities can be counted as an important dimension of the internationalization policies of higher education systems. The rise in university mobility of recent years is supported by policies that explicitly encourage these movements: scholarships and subsidies to pursue postgraduate degrees or to study parts of a bachelor’s degree in other countries, the welcoming of international students under specific programs, the internationalization of university education, etc. (Didou, 2017; Jiménez Zunino, 2020). Internationalization policies promote a certain imperative of mobility, so that graduates can access better opportunities in the academic and labor markets (Gómez & Vega, 2018).1

Internationalization is also a space for controversy. The document derived from the 2008 Conferencia Regional de Educación Superior (CRES) (Regional Conference on Higher Education), held in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia) and organized by UNESCO, was defined as an educational policy instrument that establishes higher education as a human right, in opposition to the hegemonic marketization model of universities Instituto Internacional de la UNESCO para la Educación Superior en América Latina y el Caribe (IESALC) (UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2008).

Although the importance of achieving internationalization rests on the principle of the intellectual and moral solidarity of humanity,2 in practice, the predominant south-north orientation of academic mobilities, the prevalence of the scientific and technological canons of the countries of the north, as well as the use of English as the universal language of science, privilege as a superior system the neoliberal model of the global north (Didou, 2017; Parra-Sandoval, 2022; Del Valle & Perrotta, 2023). On top of this, the granting of scholarships and subsidies for carrying out these mobilities is usually subject to the academic performance of students, their language training-depending on the destination of their mobility-, the degree program of origin, the year completed, etc. Therefore, beyond the “solidarity” support of policies that promote the internationalization of the education journeys of undergraduate and postgraduate students, attention should be paid to their selectivity.

Parallel to the phenomenon of internationalization of the higher education system, the presence of regional migrants in Argentine universities-mainly from Peru and Bolivia-also responds to the set of social mobility strategies that families already established for longer implement for the younger generations (Mallimaci Barral, 2018). Studies that address the educational experiences of migrants in Argentina focus on their presence at the primary (Domenech, 2010; Novaro, 2011) and secondary levels (Cerrutti & Binstock, 2012; Maggi & Hendel, 2019; Maggi, 2021). Moreover, some authors have warned about the importance of taking into account educational trajectories, in addition to work ones, at the intra- and intergenerational levels in migrant populations, thus being able to understand their social mobility dynamics (Oso et al., 2019) and stay strategies (Arana, 2015).

There is an increase in migrant students at UNC, who undertake their degree courses outside the circuits of internationalization programs. This increase suggests that they are economically supported by their family (Maggi et al., 2022), either from the country of origin, or in the destination country if they are established there.

Mallimaci Barral (2021) recorded the different modalities of these mobilities as including people who migrate to obtain qualifications, qualified migrants who become professionally inserted in the destination country, and people with higher education who migrate to continue their studies abroad. The author also proposes that migrant students who have gained access to Argentinian universities, even without having had the educational project as their primary goal, should be incorporated into this analysis.

These movements take place in a relatively hierarchical space of higher educational institutions, whose inequalities have deepened in recent decades with the introduction of neoliberal mechanisms in the region. South-south academic migrations are an outstanding case, since they are part of unequal university systems, which have been differentially permeated by logics of privatization and tariffs.3 The combination of free educational programs and scholarships for studies with regional migration policies encourages some countries, such as Colombia, Chile, and Peru, to issue third and fourth semester students, while others, such as Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, are receivers (Piñeros Lizarazo & Maduro Silva, 2020). It is within this framework that in recent years the Mercado Común del Sur (MERCOSUR) (Southern Common Market) has advanced a regional educational agenda that promotes educational access and the validation of degrees by member States (Sosa, 2016; Del Valle & Perrotta, 2023).

It is for all these reasons that this article investigates the heterogeneous situations and the conditions that come together in the relationship among migration, internationalization, and university education. Faced with the understanding of mobility as an imperative, it becomes especially relevant to characterize the students who can internationalize their academic journeys, taking for example the mobilities provisionally called inbound and outbound at the UNC, which involve a diversity of actors and dynamics that need to be cleared up.

Migrate to study?

In order to understand migrations for reasons of study in Argentina, both inbound and outbound, it is necessary to take a look at a structural phenomenon that during the last 15 years has manifested through the expansion of the university and scientific system.

In the decade from 2001 to 2011, the number of undergraduate students increased 22% in a context of construction of universities in the peripheral regions of the country. This expanded the geographical, and especially social, coverage by facilitating access to people who constituted the first generation with a university degree in their families (Ruta, 2015). Furthermore, Argentina is characterized by having a less restrictive higher education system in regional terms, given that 20% of students from the poorest fifth of households pursue university studies (Brunner & Ferrada Hurtado, 2011).

The proportion of people with this educational level in Argentina doubled between 1991 and 2010. According to the National Population and Housing Census, in that period the percentage of the population over 25 years of age who completed higher education (university and tertiary) increased from 8.2 to 15.6% (Dalle et al., 2019). The Greater Cordoba area exceeds the country’s total in participation at the university level, with 27.1% of young people between ages 18-and 24-years attending university, compared to 21.1% at the national level (Kaplan & Piovani, 2018, p. 236).

However, access to higher education institutions is far from being equitable, since participation in this educational level is filtered by social class. According to the analysis by Kaplan and Piovani (2018), young people between ages 18-and 24-years belonging to the upper class are those who enroll the most in higher education, all of them concentrated in the university environment (56.4%); in turn, those from the middle class reach similar figures (54.7%), yet distributed at the university and tertiary levels, tending most at the university level; while 28.5% of young people belonging to the working class access higher education, distributed at both levels. To this should be added the unequal distribution of the likelihood of completing higher education. As these authors suggest, “the higher the socioeconomic level, the greater the chances of staying in the tertiary/university educational system” (2018, p. 239). In line with this, the work of Adrogué and García de Fanelli (2021) shows that students from the middle and upper classes are more likely to pursue university studies, rather than non-university tertiary studies, that is, professorships and technical degrees.

Parallel to this, Villanueva (2017) asserted that the science and technology system developed notably in the period from 2003 to 2013: the number of researchers almost doubled (from 3 802 to 7 194), the number of scholarship beneficiaries quadrupled (from 2 221 to 8 553), and budget funds increased exponentially (from 260 to 2 900 million Argentinian pesos).

This structural situation, consistent with a scenario wherein degrees devaluate due to massification and the increase in educational credentials, it allowed to hypothesize about the search for a distinctive strategy through the internationalization of higher education. Academic mobility to other countries may work as a mechanism that allows collecting certain international resources or international capital (Wagner, 2007), at the same time providing prestige and comparative advantages in job placement. This capital enables advantageous positions in a national and international double game by accounting for the formation of capitals in the socionational structures of origin of migrant populations, at the same time being differentially valued in the receiving or sending societies (Jiménez Zunino, 2020, 2021). The symbolic differential of having contacts in prestigious international spaces can be a source of strategies of distinction and capitalization in a colonizing scheme of production and distribution of knowledge (Ramírez, 2010; França & Padilla, 2020).

It is also important to highlight the presence of students coming mainly from Mercosur member countries in Argentinian universities. These migrants are attracted by the free and unrestricted access, the variety of undergraduate and postgraduate courses, etc. (Luchilo, 2006). Dalle’s (2013, 2020) studies, which analyze the upward social mobility of migrant populations-specifically from neighboring countries-, grant the relative accessibility of the Argentinian university an important weight in understanding these migrations.

According to what was recorded in the 2020 Encuesta Nacional Migrante Argentina (ENMA) (Argentinian National Migrant Survey), the second most popular reason for immigration was educational reasons (22%) (Debandi et al., 2021). This factor contributes to the internationalization of the country’s universities, although it is not usually addressed in this way by those managing these policies. Among the age groups between 18 and 34 years, “46% stated having studied or acquired new experiences in this country as part of their immigration project” (Debandi et al., 2021, p. 31), which suggests strong bets on education in their insertion in the country. Taking into account the countries of origin, migration for educational reasons gains prominence among those who come from Ecuador (88%), Haiti (83%), Colombia (83%), and Brazil (60%) (Debandi et al., 2021).

Another interesting fact revealed by the survey is that, of the migrants surveyed, those who are currently studying are those who arrived with the highest educational levels, with 33% (university and/or postgraduate) compared to 10% (complete secondary or lower level) (Sander et al., 2021). If the age of settlement is taken into account, the ENMA results highlight that those who have lived in Argentina for fewer years are more prone to be students. Thus, “from among those who have lived here for more than 10 years, 19% are studying, while among those who have arrived in the last 5 years this percentage rises to 36%” (Sander et al., 2021, p. 114). Out of those who study, 57% pursue university degrees, while 15% opt for professional or job training.

The Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Argentina), birthplace of the University Reform of 1918 and headquarters of the last CRES in 2018, is a prestigious Latin American institution, and thus attracts many students in the region. Likewise, this center of higher education is among the four universities in the country that receive the most international students, along with the universities of Buenos Aires, La Plata, and Rosario (Sosa, 2016). In this sense, it represents a privileged scenario to observe the dynamics of the transnational academic field and the inbound and outbound mobilities of undergraduate students. In this regard, this article raises two parallel questions: how is migrant enrollment distributed at the Argentinian higher level, and particularly at UNC? And, what outbound movements occur from UNC and to what destinations?

Foreign students at unc

This section analyzes a number of characteristics of students born abroad who are enrolled in different university programs, based on data from the 2018 Statistical Yearbook (AESII, 2018; UNC, 2019). First, if the data collected by the Ministry of Education analyzed in a previous work is examined (Maggi et al., 2022), it can be observed that the participation of migrants in the entire educational system in Argentina represents 1.77% of the total enrollment, taking into account all levels of common education. The only level that exceeds two percentage points is the higher university level, where migrant enrollment reaches 3.64% (Maggi et al., 2022).

When observing specifically the province of Cordoba, it can be seen that the presence of the migrant school population is proportionally lower than the national one, representing 0.98% of the total enrollment. The proportion of migrant students in relation to the total is less than one percent in all compulsory levels. However, at the higher university level this proportion reaches 2.09%, being 2.4% at UNC (Maggi et al., 2022).

According to the same distribution by country from the ENMA 2020 (Table 1), students from Mercosur member nations at the UNC represent a higher percentage than the national index (82.24% compared to 76%), as well as those who come from non-MERCOSUR European countries (10.32% versus 8%). On the other hand, the proportion of students from non-European extra-MERCOSUR countries at UNC is less than half: 7.44% compared to 16% at the national level (Sander et al., 2021).

Table 1 Percentage of University Migrant Students in Argentina (2020) and at UNC (2018), by Grouped Nationality

| ENMA | UNC | |

|---|---|---|

| MERCOSUR | 76 | 82.24 |

| Non-European non-MERCOSUR | 16 | 7.44 |

| European non-MERCOSUR | 8 | 10.32 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Source: Own elaboration based on Sander et al., (2021, p. 116) and data provided by the Área de Estadística e Indicadores Institucionales (AESII, 2018) of the UNC.

Although the UNC does not establish a quota limit for the enrollment of students or charge any fees for undergraduate registration, the enrollment process represents a high cost for migrant students, and a bureaucratic procedure that requires a lot of foresight, mainly for non-MERCOSUR migrants-and especially those who are not Spanish speakers-. According to the Resolution no. 1731/18 of the Honorable Superior Council (UNC, 2020), in order to enroll in leveling courses in degree programs, applicants must be holders of the diploma or analytical certificate of qualifications for middle-level studies legalized by the ministry of education of the country of origin, and by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Argentinian consulate or embassy. This last legalization document can be replaced by an apostille of the documents by The Hague and, if applicable, translated by a professional registered in Argentina.

Those applicants from non-Spanish-speaking countries must also have the Certificado de Español: Lengua y Uso (CELU) (Certificate of Use of Language in Spanish), which certifies an intermediate level (very good), costing 80 USD. Once these requirements have been met, applicants can register by uploading an affidavit and official and current identification documentation (passport and identity card from the country of origin, or from Argentina). Likewise, non-MERCOSUR students who wish to continue their education must regularize their immigration status through student visas, which implies maintaining the regularity of the exams and approved subjects.4

The results in Table 1 may be related to the greater participation of the UNC in the south-south mobility processes, and to the characteristics of the province of Cordoba, which make it a desirable place to live and study. It may be so that the medium scale of the city and the symbolic value of the university combine to attract international students. As Gómez’s (2020) analysis points out in his study on migrant students at UNC:

There are previous representations about this urban space, youth life, the variety of activities, the prestige of the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba [… ]. It is an alluring urban space that moves away from the common dynamics of large cities, with a feeling of greater security and social shelter (p. 196).

If the country of birth of foreign students at UNC is taken into account (Table 2), among those from MERCOSUR the presence of Peruvians (35.2%) stands out, followed by that of Bolivians (12.7%), then Chileans (11.2%), and last Colombians (8.3%). However, the absolute numbers result more interesting, figures that allow us to measure the presence of other nationalities: 1 011 Peruvians, 363 Bolivians, 323 Chileans, 239 Colombians, 141 Venezuelans, 109 Italians, 94 Brazilians, and 91 Spaniards, these being the countries with the higher recorded figures (Maggi et al., 2022).

This diversity of students’ countries of birth suggests movements in multiple senses, which must be further analyzed in future works. The notable presence of Peruvian students can be linked to the age of this migrant flow in the city (Falcón Aybar & Boloña, 2017). Likewise, the presence of Spaniards and Italians is striking, whose mobility should be connected with the disciplinary areas of the various faculties, as well as with possible dynamics of return of emigrants from Europe.

Employment Status of Migrant Students: Full-Time Students or Working Students?

The status of migrants as full-time students or as working students may indicate the presence of local or transnational support networks that send remittances to support the studies of these migrants. The situation in relation to students’ work guides them towards different educational trajectories, but also towards more or less successful professional insertions, as in the case of pre-professional practices and internships in many careers (Panaia, 2009; Pérez & Busso, 2015). In this analysis, it is assumed that the most favorable condition for students is not to work or look for work (and thus have all the time to study); on the other hand, the worst scenario is to work, or having to look for a job (due to workload, duplication of tasks, fatigue, financial constraints, etc.).

As such, an approximation can be established to the conditions of students born abroad in relation to two variables: their employment situation (Table 2), and the way their studies are financed (Table 3). Both variables provide clues to continue exploring the diverse situations in which migrant students find themselves at UNC.

Table 2 UNC Students by Employment Status, by Country of Birth, 2018*

| Country of birth | Employment status | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Works | Does not work and is looking for work | Does not work and is not looking for work | No data | Total | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| MERCOSUR | Peru | 464 | 46.2 | 298 | 29.7 | 241 | 24 | 2 | 0.2 | 1 005 | 100 |

| Bolivia | 119 | 32.8 | 82 | 22.6 | 160 | 44.1 | 2 | 0.6 | 363 | 100 | |

| Chile | 112 | 34.7 | 97 | 30 | 113 | 35 | 1 | 0.3 | 323 | 100 | |

| Colombia | 116 | 48.5 | 85 | 35.6 | 37 | 15.5 | 1 | 0.4 | 239 | 100 | |

| Venezuela | 81 | 57.4 | 37 | 26.2 | 23 | 16.3 | 0 | 0 | 141 | 100 | |

| Brazil | 34 | 39.1 | 31 | 35.6 | 22 | 25.3 | 0 | 0 | 87 | 100 | |

| Ecuador | 24 | 29.6 | 22 | 27.2 | 35 | 43.2 | 0 | 0 | 81 | 100 | |

| Paraguay | 39 | 50 | 15 | 19.2 | 24 | 30.8 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 100 | |

| Uruguay | 17 | 54.8 | 3 | 9.7 | 11 | 35.5 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 100 | |

| Total | 1 006 | 42.8 | 670 | 28.5 | 666 | 28.4 | 6 | 0.3 | 2 348 | 100 | |

| Non-European non-MERCOSUR | United States | 25 | 36.8 | 8 | 11.8 | 35 | 51.5 | 0 | 0 | 68 | 100 |

| Australia | 2 | 15.4 | 5 | 38.5 | 6 | 46.2 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 100 | |

| China | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 87.5 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 100 | |

| Canada | 5 | 71.4 | 2 | 28.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 100 | |

| Mexico | 3 | 42.9 | 3 | 42.9 | 1 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 100 | |

| Haiti | 1 | 20 | 2 | 40 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100 | |

| Rest of the Americas | 22 | 34.9 | 28 | 44.4 | 13 | 20.6 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 100 | |

| Africa | 4 | 25 | 4 | 25 | 8 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 100 | |

| Rest of Asia | 9 | 32.1 | 5 | 17.9 | 14 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 100 | |

| Total | 72 | 33.5 | 57 | 26.5 | 86 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 215 | 100 | |

| European non-MERCOSUR (continuation) | Italy | 38 | 34.9 | 25 | 22.9 | 46 | 42.2 | 0 | 0 | 109 | 100 |

| Spain | 29 | 31.9 | 17 | 18.7 | 45 | 49.5 | 0 | 0 | 91 | 100 | |

| Germany | 23 | 65.7 | 2 | 5.7 | 10 | 28.6 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 100 | |

| (continues) | |||||||||||

| France | 13 | 52 | 5 | 20 | 7 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 100 | |

| Rest of Europe | 17 | 47.2 | 9 | 25 | 10 | 27.8 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 100 | |

| Total | 120 | 40.5 | 58 | 19.6 | 118 | 39.9 | 0 | 0 | 296 | 100 | |

| Total | 1 198 | 41.9 | 785 | 27.5 | 870 | 30.4 | 6 | 0.2 | 2 859 | 100 | |

* Due to the low proportion of students from China, Canada, Mexico, and Haiti who responded to this question, it was decided not to include them into the analysis, but to still keep them in this table. It should also be clarified that the continental groupings were generated in this way by the primary source.

Source: Own elaboration based on data provided by the Área de Estadística e Indicadores Institucionales (AESII, 2018) of the UNC.

As for the employment situation of UNC students, 39.3% work, 21.9% are unemployed but are looking for a job, and 38.3% do not work or look for employment (0.5%, n. d.) (UNC, 2019, p. 96). On the other hand, of all UNC migrant students, 42% work, 27.5% do not but are looking for employment, and 30% do not work or look for employment. When grouped according to the classification proposed by ENMA, it was found that the majority of students at UNC coming from Mercosur countries are those who set the trend: almost 43% work (three percentage points above the total).

On the other hand, from among those who do not work, the proportion of those seeking employment is very similar to that of those not seeking employment (28.5% versus 28.4%). However, looking at some nationalities, it stands out that those who do not work or seek employment reach between five and six percentage points above the total number of students: this is the case of Bolivians (44.1%) and Ecuadorians (43.2%). This may be indicative of these being more settled groups, who may live in the home of their migrant parents (in the case of Bolivians), or of them being training projects supported from the country of origin, questions that are formulated as hypotheses.

Of the group of students from non-European non-MERCOSUR national origins, a third of them works, 26.5% does not but is looking for employment, and 40% does not work or look for employment, a proportion that is also above the total number of students from the UNC. Whereas among students from European countries, it was observed that 40.5% work, 19.6% do not work and are looking for employment, and 39.9% do not work or look for employment. Among the most representative nationalities, Italians (42.2%) and Spaniards (49.5%) were found in the favorable position of being full-time students.

Next, the booked way of paying for studies is analyzed (Table 3), taking into account that the answer to this question from the UNC statistics system is multiple, and that the percentages do not represent exclusive options. As expected, most of the students are financially supported by their families (almost all, above 50%, have this source of financing): 62.2% of Argentinians, more than 50% of Peruvians, 61.7% of those from Bolivia, and 57.4% of Chileans. Some complement and others fully finance themselves their studies by being employed; a few of them do so by means of scholarships or social plans. Venezuelans (56.6%) and Colombians (50.2%) were among the migrant groups with the highest percentage of responses in the employed option, both above the general average of responses in the entire UNC, which is around a third of students.

Table 3 UNC Students by Country of Birth and way of Paying for Their Studies (Valid Cases), 2018*

| Country of birth | Family support | Employed | Scholarships | Social plans | Others | Totals | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 1. Argentina | 92 136 | 62.2 | 45 772 | 30.9 | 5.099 | 3.4 | 3 320 | 2.2 | 1 860 | 1.3 | 148 187 | 100 | |

| 2. Peru | 598 | 50.6 | 490 | 41.5 | 32 | 2.7 | 28 | 2.4 | 33 | 2.8 | 1 181 | 100 | |

| 3. Bolivia | 271 | 61.7 | 136 | 31 | 10 | 2.3 | 12 | 2.7 | 10 | 2.3 | 439 | 100 | |

| 4. Chile | 237 | 57.4 | 146 | 35.4 | 12 | 2.9 | 3 | 0.7 | 15 | 3.6 | 413 | 100 | |

| 5. Colombia | 123 | 44.4 | 139 | 50.2 | 3 | 1.1 | 4 | 1.4 | 8 | 2.9 | 277 | 100 | |

| 6. Venezuela | 61 | 40.1 | 86 | 56.6 | 1 | 0.7 | 2 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.3 | 152 | 100 | |

| 7. Italy | 92 | 65.7 | 39 | 27.9 | 6 | 4.3 | 1 | 0.7 | 2 | 1.4 | 140 | 100 | |

| 8. Brazil | 54 | 51.9 | 46 | 44.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.9 | 104 | 100 | |

| 9. Spain | 73 | 65.2 | 27 | 24.1 | 5 | 4.5 | 5 | 4.5 | 2 | 1.8 | 112 | 100 | |

| 10. Ecuador | 69 | 70.4 | 23 | 23.5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4.1 | 98 | 100 | |

| 11. Paraguay | 52 | 53.6 | 37 | 38.1 | 2 | 2.1 | 4 | 4.1 | 2 | 2.1 | 97 | 100 | |

| 12. United States | 58 | 75.3 | 16 | 20.8 | 2 | 2.6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.3 | 77 | 100 | |

| 13. Germany | 21 | 45.7 | 21 | 45.7 | 3 | 6.5 | 1 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 100 | |

| 14. Uruguay | 19 | 52.8 | 16 | 44.4 | 1 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 100 | |

| 15. France | 21 | 72.4 | 7 | 24.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.4 | 29 | 100 | |

| 16. Haiti | 24 | 77.4 | 7 | 22.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 100 | |

| 17. Mexico | 19 | 70.4 | 5 | 18.5 | 1 | 3.7 | 2 | 7.4 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 100 | |

| Africa | 5 | 50 | 4 | 40 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 100 | |

| Asia | 22 | 64.7 | 12 | 35.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 100 | |

| Oceania | 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 100 | |

| Rest of the Americas | 39 | 54.9 | 23 | 32.4 | 4 | 5.6 | 1 | 1.4 | 4 | 5.6 | 71 | 100 | |

| Rest of Europe | 24 | 57.1 | 14 | 33.3 | 2 | 4.8 | 1 | 2.4 | 1 | 2.4 | 42 | 100 | |

| No data | 1 528 | 32 | 3 006 | 63 | 85 | 1.8 | 37 | 0.8 | 117 | 2.5 | 4 773 | 100 | |

| Total | 95 552 | 61.1 | 50 072 | 32 | 5 270 | 3.4 | 3 424 | 2.2 | 2 064 | 1.3 | 156 382 | 100 | |

* Multiple answer question.

Source: Own elaboration based on data provided by the Área de Estadística e Indicadores Institucionales (AESII, 2018) of the UNC.

Approximation to the Social (Educational) Origin of Migrant Students

Finally, in order to achieve an approximation to the social origin of the students, a comparative analysis of the educational levels achieved by the mother and father of nationals and those born abroad was carried out (Table 4).5 The educational level of the parents is used as a proxy variable for social origin, since it can provide indications of different stocks of institutionalized cultural capital available in the families that support the education of their children. It is also taken as an indicator of the equity gaps in educational systems, which in the Argentinian case are far from being egalitarian: as Adrogué and García de Fanelli (2021) have pointed out, students who enroll in university as first timers in their families-what is known as first generation-are four times less likely to succeed than those whose parents have a university degree (p. 46).

In other studies on Cordoba, the characteristics of social classes were reconstructed, with the university educational level of the heads of household being one of the core dimensions for the characterization of the upper class (Gutiérrez & Mansilla, 2015; Jiménez Zunino, 2019). Meanwhile, the data analyzed evidenced important differences between Argentinian and migrant students at UNC in relation to the educational level of their parents. While the largest proportion of the parents of Argentinian students-both native and by choice, as well as naturalized-have completed secondary school as their highest level of education, for the parents of migrants the highest level achieved is completed university.

Overall, those who proportionally show higher levels of education are the parents of migrant students; while those who have the lowest educational levels in percentage terms are the naturalized Argentinian students6 (what is more, the third most recurrent level of education achieved by their mothers is incomplete primary school). This can evoke interpretations about different social backgrounds of students with mobility/migration experiences that take place at UNC; taking into account the percentage values of the educational levels achieved by the parents of naturalized Argentinians and migrant students, it would be interesting to continue exploring whether these differences respond to the distinction between those who come to study (recently arrived) and those who, living in Argentina, are studying (settled for longer).

Table 4 Students by Highest Level of Education Achieved by Mother and Father, by Nationality, 2018

| Father | Mother | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student nationality | Native Argentinian | Argentinian by choice | Naturalized | Foreign | Native Argentinian | Argentinian by choice | Naturalized | Foreign | ||

| HIGHEST EDUCATIONAL LEVEL | No education | N | 614 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 360 | 20 | 5 | 0 |

| % | 0.7 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 0 | ||

| Incomplete primary | N | 4 104 | 83 | 10 | 5 | 2 859 | 102 | 19 | 7 | |

| % | 4.9 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 6.9 | 11.9 | 4.8 | ||

| Complete primary | N | 8 874 | 89 | 7 | 8 | 7 667 | 106 | 15 | 4 | |

| % | 10.6 | 6.3 | 4.5 | 5.8 | 8.8 | 7.1 | 9.4 | 2.7 | ||

| Incomplete secondary | N | 13 612 | 132 | 22 | 10 | 10 503 | 155 | 19 | 10 | |

| % | 16.3 | 9.3 | 14.1 | 7.2 | 12.1 | 10.5 | 11.9 | 6.8 | ||

| Complete secondary | N | 19 898 | 408 | 46 | 26 | 18 174 | 365 | 38 | 26 | |

| % | 23.8 | 28.8 | 29.5 | 18.8 | 21 | 24.6 | 23.9 | 17.8 | ||

| Incomplete higher | N | 2 243 | 74 | 11 | 5 | 2 939 | 70 | 5 | 5 | |

| % | 2.7 | 5.2 | 7.1 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 3.4 | ||

| Complete higher | N | 6 075 | 137 | 11 | 8 | 14 704 | 188 | 27 | 24 | |

| % | 7.3 | 9.7 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 17 | 12.7 | 17 | 16,4 | ||

| Incomplete university | N | 10 006 | 112 | 19 | 8 | 7 965 | 97 | 8 | 11 | |

| % | 12 | 7.9 | 12.2 | 5.8 | 9.2 | 6.5 | 5 | 7,5 | ||

| Complete university | N | 15 096 | 252 | 22 | 46 | 17 948 | 291 | 18 | 43 | |

| % | 18.1 | 17.8 | 14.1 | 33.3 | 20.7 | 19.6 | 11.3 | 29.5 | ||

| Postgraduate | N | 3 037 | 116 | 3 | 22 | 3 575 | 89 | 5 | 16 | |

| % | 3.6 | 8.2 | 1.9 | 15.9 | 4.1 | 6 | 3.1 | 11 | ||

| Total | N | 83 559 | 1 415 | 156 | 138 | 86 694 | 1 483 | 159 | 146 | |

| % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

Source: Own elaboration based on data provided by the Área de Estadística e Indicadores Institucionales (AESII, 2018) of the UNC.

Outbound UNC students: potential emigrants?

As noted at the beginning of this article, international academic mobility constitutes a way of accumulating international capital, which can provide prestige and comparative advantages in competitive the labor market. This implies understanding student mobility (aimed at completing a degree or pursuing postgraduate studies) as one of the social mobility strategies deployed by migrants and their families. As asserted by Martínez Pizarro (2010), displacement itself embodies, to a certain extent, the possibility of migration, since: “many university students, particularly postgraduates, are decidedly candidates to become brains or talents among the workforce, given the skills that education has thought them” (p. 141).

The first subsection analyzes a database provided by the UNC Prosecretaría de Relaciones Internacionales (International Relations Office) (PRI-UNC, 2019), so as to characterize the departures of students between years 2006 and 2019. The second subsection examines some results of the Encuesta de movilidad saliente (Outbound Mobility Survey) (Jiménez Zunino & PRI-UNC),7 to characterize mobile subjects according to their social origins.

Main Destinations of Outbound Student Mobility from the UNC

In terms of outbound student mobility as a whole, Argentina is not among the countries sending out the most: in 2014, while Brazil reached 15.41 per thousand and Mexico 13 per thousand, Argentina only registered 3.4 per thousand (Didou, 2017, p. 31). Some authors point out that internationalization is quite punctual and reduced in this country, compared to the volume of the national university system (Ruta, 2015). Even so, according to data compiled by UNESCO (2021), it is possible to distinguish the main countries preferred by Argentinians to carry out their studies: first place is the United States (2 151 students); second place is Spain (1 296); and third Brazil (1 032). The fourth and fifth place are Germany (734 students) and France (539), respectively, out of a total of 9 129 outbound students recorded in 2018.

The data from the database provided by the PRI records a total of 1 403 departures from UNC between 2006 and 2019, including undergraduate students (94.8%) who enroll in various programs to complete and/or complement their degrees and, to a lesser extent, postgraduate students who undertake their courses, or part of them, in foreign institutions (the different postgraduate levels adding up to 5.2%) (Table 5).

Table 5 Outbound UNC Student Mobility by Higher Level in Progress at the Time of Stay, 2006-2019

| Higher level | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Degree | 1 330 | 94.8 |

| Postgraduate | 73 | 5.2 |

| Total | 1 403 | 100 |

Source: Own elaboration based on data provided by the Prosecretaría de Relaciones Internacionales (PRI-UNC, 2019).

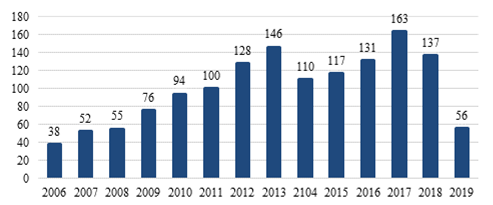

Taking into account the timeline (Graph 1), the largest number of departures took place in 2017, and then in 2013. It is noteworthy that a possible interpretation of these data has to do with the ups and downs in the Argentinian economy, and with the fluctuations in the exchange rate of the dollar, the currency to which trips abroad are bound. Still, some matters of interest can be inferred; the data on the main destinations were grouped according to the language of the places, and it was confirmed that more than half of the trips enabled by PRI-UNC programs were bound to Spanish-speaking countries, including both Latin American countries (33.1%) and Spain (19.9%) (Table 6).

Source: Own elaboration based on data provided by the Prosecretaría de Relaciones Internacionales International Relations Office (PRI-UNC, 2019).

Graph 1 Outbound UNC Student Mobility by Year, 2006-2019

Table 6 Destination of Outbound UNC Student Mobility, 2006-2019

| Region or country | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Latin America (Spanish speaking) | 464 | 33.07 |

| Brazil | 371 | 26.44 |

| Spain | 279 | 19.89 |

| United States | 27 | 1.92 |

| Canada | 41 | 2.92 |

| Europa (non-Spanish speaking) | 142 | 10.12 |

| Asia | 2 | 0.14 |

| No data | 77 | 5.5 |

| Total | 1 403 | 100 |

Source: Own elaboration based on data provided by the Prosecretaría de Relaciones Internacionales (PRI-UNC, 2019).

Language is another factor that guides these movements. Whether at the undergraduate or graduate level, the language defines the destination abroad to a large extent (Trejo Peña & Suárez Bequir, 2018). The second most chosen place to travel within the framework of academic stays is Brazil (26%), something that is possibly related to the mastering of the Portuguese language (the second after English, as will be seen later) and to the feedback on the knowledge that internationalization experiences entail.

Still, 35% of outbound mobility was in the south-north direction, accounting for the stays in the United States, Canada, and Europe. Although these data can guide interpretations about the impact of language on the direction of flows, the academic prestige of countries in the global north can be the deciding factor in the choices of many journeying students.

One fact that may alleviate fears of brain drain from this type of experiences is the low proportion of residents abroad detected through the survey.8 Of all the respondents, only 15 lived abroad at the time of the survey. Many have migrated to other provinces within Argentina, something that can be explored in depth in future investigations on internal mobilities triggered after experiences abroad.

Social Origins of Outbound Students

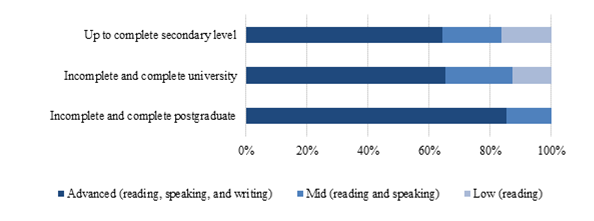

One of the sections of the Outbound Mobility Survey addresses the educational level of the father and mother of those who underwent internationalization experiences. Of the parents of all those surveyed, 41% are professionals (completed university), and if parents with incomplete university and those with postgraduate studies (complete and incomplete) are added, the figure reaches 70% of the sample (Table 7). Additionally, a small group has parents with a postgraduate educational level (15%), either complete or incomplete.

Table 7 Educational Level of Parents of Outbound UNC Students, 2006-2019

| Educational level | Father | Mother | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up to complete secondary level | N | 73 | 56 |

| % | 30.54 | 23.43 | |

| Incomplete and complete university | N | 132 | 141 |

| % | 55.24 | 59 | |

| Incomplete and complete postgraduate | N | 34 | 42 |

| % | 14.22 | 17.57 | |

| Total | N | 239 | 239 |

| % | 100 | 100 | |

Source: Own elaboration based on data from the Encuesta de movilidad saliente (Jiménez Zunino & PRI-UNC, 2019-2020).

For their part, the mothers have similar educational levels: half are professionals, and added to those who have completed university studies and postgraduate studies (complete and incomplete), they exceed two thirds of the total sample. The social origins of the respondents, taking into account the parents’ qualifications, correspond to middle class, given the institutionalized cultural capital owned by these families (Goldthorpe, 1994; Bourdieu, 2011). In contexts of massification and devaluation of degrees, families that have been accumulating diplomas since the previous generation deploy academic strategies that tend towards specialization, such as obtaining postgraduate degrees, and internationalization. These distinctive practices aim at the acquisition of symbolic instruments of legitimation of the highest positions within the social structure (Jiménez Zunino, 2020).9

When it comes to the educational levels achieved by the migrant students at the time of the survey, all had completed their bachelor’s degree, and the majority had begun and, in some cases, also completed postgraduate studies (53%). The degrees of the latter range from specialization studies, where the proportion of women (16%) is more than double that of men (7%); master’s degree, preferred by men (25%) compared to women (7%); to doctorate, where the gender gaps are narrow: 24% of men compared to 19% of women. However, a high proportion of respondents did not complete any postgraduate studies: 44% of men and 48% of women (see Table 8).

Table 8 Graduate Studies by Gender of Outbound UNC Students at the Time of the Survey, 2006-2019

| Gender | Doctorate | Specialization | Master’s Degree | N | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | N | 29 | 25 | 26 | 75 | 155 |

| % | 18.71 | 16.13 | 16.77 | 48.39 | 100 | |

| Male | N | 20 | 6 | 21 | 37 | 84 |

| % | 23.81 | 7.14 | 25 | 4405 | 100 | |

| Total | N | 49 | 31 | 47 | 112 | 239 |

| % | 20.50 | 12.97 | 19.67 | 46.86 | 100 | |

Source: Own elaboration based on data from the Encuesta de movilidad saliente (Jiménez Zunino & PRI-UNC, 2019-2020).

Delving deeper into the social origin of those who complete postgraduate studies, in 73% of the cases, one of the parents of those who attend this level of education also hold university and postgraduate studies, which would account for a significant intergenerational reproduction of institutionalized cultural capital, in a third and fourth cycle. However, a considerable part of the respondents accessed postgraduate studies from social origins relatively less provided with cultural capital (27% of fathers and 20% of mothers completed secondary school at most).

The greater student access to postgraduate levels can be explained by the impact of public policy on education, referred to in previous pages, as well as due to the increase in the budget allocated to science and technology, and the quadrupling of scholarships for postgraduate studies between 2003 and 2013 and to support university enrollment (Villanueva, 2017). It should be noted that these students, in addition to being the first generation of graduates in their families, also have fourth-level degrees. In addition, 60% of those surveyed who completed postgraduate studies had scholarships from public organizations, predominantly from the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) National Scientific and Technical Research Council) and the UNC.

However, the literature specialized in academic mobilities has warned about the selective nature of internationalization experiences, since they rely on the financing capacities of families (Pedone & Alfaro, 2015; Didou, 2017). In this research, 70% of those surveyed had to assume extra costs for their mobility and stays, aside from the resources provided by the scholarship. This condition mostly impacts students who fewer financial resources, which conditions their lesser access to these internationalization experiences.

Another indicator to account for in order to identify the social selectivity that these mobilities entail is the mastery of second languages other than Spanish. The aforementioned study by Kaplan and Piovani (2018) highlights the differences by social class in foreign language skills. Among young people between ages 18 and 29-years, the lack of knowledge of a language other than Spanish is 21.7% in the upper class; 39.8% in the middle class, and 58.3% in the working class. These percentages decrease among higher education students, but reveal strong regional disparities in the country.

In the present study, when asking respondents about their level of command of a foreign language, 68% stated having high-level English, and 20% stated mid-level.10 Observing differences by gender, the proportion of women is double that of men in terms of a high-level English. The second most mastered language among those surveyed is Portuguese, about which 28% stated having high level.

The possibility of moving, as well as the choice of destinations, are facilitated by the command of a second languages. More than half of the mobility was bound to Spanish-speaking destinations, as mentioned in previous pages. This shows, on the one hand, the delimitation of the available scholarships-which may be oriented towards regional integration, as mentioned at the beginning of this article-; and, on the other hand, the skill at second languages Likewise, looking back to what was analyzed above on the social origins of the parents based on their educational level, the relationship with language proficiency is also noted, especially in the English language. Thus, when comparing the father’s educational level with the child’s skill in the use of this language, it can be seen that both factors are correlated (Graph 2): respondents who stated a high level of English have parents with a higher educational level (especially postgraduate). In contrast, those of mid- or low-level proficiency in this language have parents with a lower educational level (complete secondary school).

Source: Own elaboration based on data from the Encuesta de movilidad saliente (Jiménez Zunino & PRI-UNC, 2019-2020).

Graph 2. Parent’s Educational Level and Student’s English Proficiency

Closing thoughts

The main contribution of this article lies in analyzing simultaneously mobilities that are usually observed separately; that is, the migrant presence in the university system and academic mobilities within the framework of internationalization programs. The study’s attention focused on the heterogeneity and inequalities that cut across these trajectories. Such inequalities were analyzed in this text by referring to two axes, mainly. On the one hand, relatively hierarchical spaces among regions were identified, that attract students from different countries/regions. On the other hand, social class inequalities were detected, from the confirmation of a strong selectivity of those who can sustain internationalized trajectories.

In relation to the first axis, the solidarity support that underpins, according to UNESCO, internationalization policies in their implementation was called into question (Parra-Sandoval, 2022; Del Valle & Perrotta, 2023), since destinations abroad tend strongly towards the north (35%), and towards Spanish-speaking regions (53%). These mobilities are related to stratified academic circulation spaces, both due to the institutional dynamics in which they are framed (financing, agreements, scholarships, validation of degrees and studies, language accreditations, etc.), and due to forms of capital (languages, money, contacts) possessed by the students themselves, which determines the various itineraries of their mobilities.

Considering the above, and deploying the second axis of inequality analyzed, these mobilities are mostly related to a relatively select social sector, since access to the university, and even more so, to internationalization, are presented as mechanisms of social reproduction that are strongly economically and culturally conditioned. According to the background addressed in this article, although access to the university is greater now (Dalle et al., 2019), strong inequalities persist at higher educational levels (tertiary or university) (Adrogué & García de Fanelli, 2021; Kaplan & Piovani, 2018; Adrogué & García de Fanelli, 2021). Likewise, the proportion of young people who attend university differs by social class, as evidenced by the social origins of the students-both those in outbound mobility and immigrants-estimated based on the educational level of their parents.

In the case of the migrant population in Argentina, specialized literature confirms the value of investing in education in upward social mobility strategies (Novaro, 2011; Cerrutti & Binstock, 2012; Dalle, 2013, 2020; Arana, 2015; Maggi, 2021). The ENMA even demonstrated that studying is the second motivation of many migrants to reside in Argentina (Debandi et al., 2021), especially among those arriving most recently, oriented as they are toward undergraduate and postgraduate studies (Sander et al., 2021). The present analysis showed that, in the specific case of the UNC, there is a greater presence of students from the European MERCOSUR and non-MERCOSUR region-in relation to what is recorded in the ENMA for the total number of cases in the country-, which should be further addressed in future works.

Social inequality in access to university and internationalization is manifested in the employment situation of students (those who are full-time students versus those who also work), in the way they pay for higher education, in the education levels of their parents, and in their language skills. The situation of students who do not work, as well as those who receive financial help from their family to study, suggest conditions more favorable for them to undertake migratory projects for study purposes.

At the same time, the findings of the survey conducted on outbound mobility students showed the option of staying abroad for periods of time to be a preferred choice. The results of this first stage of the research support a certain explanatory circularity. According to this, those who have more advantaged social positions would have better conditions and greater possibilities to move abroad. This is explained by the existence of a more familiar relationship with cultural capital of an institutionalized and incorporated type, either due to the educational levels of the parents or due to mastery of a second language. Added to this is the economic capital required, in a large number of cases, to complement otherwise insufficient scholarships.

However, a considerable percentage of students skipped two educational steps, as they accessed the fourth level (postgraduate) having fathers and mothers with educational levels lower than complete secondary school. This particularity of the sample studied (students who experienced outbound academic mobility) must be contrasted with the studies by Adrogué and García de Fanelli (2021). Although this accumulation of fourth-level degrees can also be attributed to the opportunity that postgraduate scholarships (from CONICET and UNC) have represented during the last decade and a half (Villanueva, 2017).

Furthermore, students born abroad displayed two profiles in relation to the educational level of their parents. A group was observed that has parents with an educational level up to incomplete primary school, while the other, more numerous group has parents with higher education (undergraduate and postgraduate). Both groups of foreign students are over-represented compared to those considered actually Argentinian. This first analysis revealed a great heterogeneity in the inbound UNC student body, that is, those who were born abroad and are studying at this institution.

The greater access to higher education in recent decades and the possible risk of devaluation of degrees can be overcome, by some social sectors, if they resort to the internationalization of training experiences. Internationalization provides additional capital, international capital (Wagner, 2007), which could facilitate job placements. However, there are nuances to take into account for future analysis; one of them is that the accumulation of cultural capital, which would seem to be behind these bets, is neither linear nor sustained. Thus, the proportion of people who stayed abroad for a period of time and did not continue postgraduate studies is considerable. Although international mobility is part of an academic experience, it is possible for academic careers not to be the core of the work project of many of these young people. Given this, it is worth asking: how are these international mobility experiences assessed in the labor market-outside the academic field-?

On the other hand, are the students born abroad who are at UNC migrants who have managed to get into the university after the migratory experience with their parents? Or are those who are able to undertake internationalization experiences in Cordoba rather select students in their country of origin? These first findings warn on the need to delve into this diversity, which reveals basic inequalities if the analyzed variables are all taken into account (educational level of the parents, way of paying for studies, employment situation, and others that can be added in qualitative inquiries). Complementary research will be important for future works, research that goes deeper into migratory trajectories (age of migration, main motivations, itineraries prior to settling in Cordoba, etc.) to account for the particularities of each group. This will allow a knowledge better attuned to the set of conditions in which migrant students find themselves, and thus make it possible to construct precise indicators and categories for institutional support of their university journeys.

The dynamics of student mobility explored in this article and inscribed in the asymmetrical conformation of central and peripheral regions (Kreimer, 2012; Del Valle & Perrotta, 2023), are closely linked to the class origins and the unequal possibilities of the subjects (given the capitals possessed to move on the international stage: linguistic and economic, mainly). This represents great challenges for addressing university internationalization policies in the current context. Thus, in addition to existing scholarships, universities and educational organizations have the challenge of generating new inclusion mechanisms to promote these formative experiences.

Translation: Fernando Llanas.

REFERENCES

Adrogué C. García de Fanelli A. 2021. Brechas de equidad en el acceso a la educación superior argentina. Páginas de Educación, 14(2), 28-51. [ Links ]

Arana T. 2015. Que tengan su carrera, que sean algo en la vida, no como uno que no tiene profesión y hace lo que puede Master’s thesis, unpublished, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes. [ Links ]

Área de Estadística e Indicadores Institucionales (AESII) 2018. Base de datos del Anuario Estadístico de la UNC 2018 [Unpublished data set]. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. [ Links ]

Bourdieu P. 2011. Las estrategias de reproducción social. Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Brunner J. Ferrada Hurtado R. 2011. Educación superior en Iberoamérica. Informe 2011. Centro Interuniversitario de Desarrollo. [ Links ]

Cerrutti M. Binstock G. 2012. Los estudiantes inmigrantes en la escuela secundaria. Integración y desafíos. UNICEF. [ Links ]

Dalle P. 2013. Movilidad social ascendente de familias migrantes de origen de clase popular en el Gran Buenos Aires. Trabajo y Sociedad, 21, 373-401. http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?pid=S1514-68712013000200024&script=sci_arttext&tlng=es [ Links ]

Dalle P. 2020. Movilidad social a través de tres generaciones: Huellas de distintas corrientes migratorias. En: Sautu R. Boniolo P. Dalle P. Elbert R. (eds.). El análisis de clases sociales. Pensando la movilidad social, la residencia, los lazos sociales, la identidad y la agencia (pp. 91-133). Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani; Clacso. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1gn3t2q.6 [ Links ]

Dalle P. Boniolo P. Navarro-Cendejas J. 2019. Efectos del origen social familiar en el logro educativo en el nivel superior en Argentina y México. Caminos diferentes, desigualdades similares. Educación y Derecho, 19, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1344/reyd2019.19.29091 [ Links ]

Debandi N. Hendel V. Nicolao J. 2021. Trayectorias y proyectos migratorios. En: Debandi N. Nicolao J. Penchaszadeh A. (eds.). Anuario estadístico migratorio de Argentina 2020 (pp. 25-38). Red de Investigaciones en Derechos Humanos-CONICET; Encuesta Nacional Migrante de Argentina. [ Links ]

Del Valle D. Perrotta D. 2023. Internacionalización universitaria y movilización política. Instituto de Estudios de Capacitación-Conadu; Clacso. [ Links ]

Didou S. 2017. La internacionalización de la educación superior en América Latina: transitar de lo exógeno a lo endógeno. Unión de Universidades de América Latina y el Caribe. [ Links ]

Domenech E. 2010. Etnicidad e inmigración: ¿hacia nuevos modos de integración en el espacio escolar?. Astrolabio, 1(1), 1-12. https://www.aacademica.org/eduardo.domenech/29 [ Links ]

Falcón Aybar M. del C. Bologna E. 2017. Migrantes antiguos y recientes: una perspectiva comparada de la migración peruana a Córdoba, Argentina. Migraciones Internacionales, 6(24), 235-266. https://doi.org/10.17428/rmi.v6i24.715 [ Links ]

França T. Padilla B. 2020. Movilidad académica de latinoamericanos hacia Europa: Reproduciendo los patrones de la migración Sur-Norte. En: Sassone S. Padilla B. González M. Matossian B. Melella C. (eds.). Diversidad, migraciones y participación ciudadana: identidades y relaciones interculturales (pp. 181-201). Instituto Multidisciplinario de Historia y Ciencias Humanas. [ Links ]

García Garza D. Wagner A. 2015. L’internationalisation des “savoirs” des affaires. Les Business Schools françaises comme voies d'accès aux élites mexicaines. Cahiers de la recherche sur l'éducation et les savoirs, 14, 141-162. https://journals.openedition.org/cres/2791?lang=en [ Links ]

Goldthorpe J. 1994. Sobre la clase de servicio, su formación y su futuro. En: Carabaña J. de Francisco A. (eds.). Teorías contemporáneas de las clases sociales (pp. 229-263). Pablo Iglesias. [ Links ]

Gómez C. Vega C. 2018. El imperativo de movilidad y los procesos de precarización en Educación Superior. Docentes e investigadores españoles entre Ecuador y España. Revista Iberoamericana de Estudios de Desarrollo, 7(1), 168-191. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6408256 [ Links ]

Gómez S. 2020. Derecho a la educación superior en Latinoamérica y migraciones hacia las universidades estatales argentinas. Paideia Surcolombiana, 25, 184-204. https://doi.org/10.25054/01240307.2535 [ Links ]

Gutiérrez A. Mansilla H. 2015. Clases y reproducción social: el espacio social cordobés en la primera década del siglo XXI. Política y Sociedad, 52(2), 409-442. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_POSO.2015.v52.n2.44467 [ Links ]

Jiménez Zunino C. 2019. Modo de reproducción escolar en las clases sociales cordobesas. Un análisis desde las transmisiones intergeneracionales. Temas Sociológicos, 25, 291-327. https://doi.org/10.29344/07196458.25.2171 [ Links ]

Jiménez Zunino C. 2020. Capital internacional en las movilidades externas de la UNC. 1991. Estudios Internacionales, 2(2), 182-221. https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/revesint/article/view/32634 [ Links ]

Jiménez Zunino C. 2021. Internacionalización a medida: movilidades salientes de estudiantes de clases medias cordobesas. En: Pedone C. Gómez Martín C. (eds.). Los rostros de la migración cualificada: estudios interseccionales en América Latina (pp. 123-154). Clacso. [ Links ]

Jiménez Zunino C. Prosecretaría de Relaciones Internacionales (PRI-UNC) 2019-2020. Encuesta de movilidad saliente de la UNC, 2019 (STAN-CONICET ST 4954) ]Data set[. UNC-Instituto de Humanidades; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScz0uSsdVBD5AGfN0l9-yZ4QsHDCj0QPp0p2ebFmAWNGDEAAA/viewform?vc=0&c=0&w=1 [ Links ]

Kaplan C. Piovani J. I. 2018. Trayectorias y capitales socioeducativos. En: Piovani J. L. Salvia A. (eds.). La Argentina en el siglo XXI. Cómo somos, vivimos y convivimos en una sociedad desigual. Encuesta Nacional sobre la Estructura Social (pp. 221-263). Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Kreimer P. 2012. Les enjeux de la formation des élites scientifiques en Amérique Latine. Amerique Latine, 105-116. [ Links ]

Luchilo L. 2006. Movilidad de estudiantes universitarios e internacionalización de la educación superior. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencia, Tecnología y Sociedad, 3(7), 105-133. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/924/92430707.pdf [ Links ]

Maggi M. F. 2021. Apuestas educativas como forma de territorialización de familias migrantes bolivianas en la ciudad de Córdoba, Argentina. Periplos, 5(2), 193-223. http://hdl.handle.net/11336/148320 [ Links ]

Maggi M. F. Hendel V. 2019. Experiencias escolares desde el prisma del desplazamiento. Temas de Antropología y Migración, 11, 11-35. http://hdl.handle.net/11336/131139 [ Links ]

Maggi M. F. Sciolla P. Pérez E. Jiménez Zunino C. Rodríguez Rocha E. 2022. Los inmigrantes en el sistema educativo cordobés (2017-2019). Centro de Estudios Avanzados-Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. https://rdu.unc.edu.ar/handle/11086/26459 [ Links ]

Mallimaci Barral A. 2018. Circulaciones laborales de mujeres migrantes en Buenos Aires: de empleadas domésticas a enfermeras. Cadernos Pagu, 54. https://doi.org/10.1590/18094449201800540012 [ Links ]

Mallimaci Barral A. 2021. Entre estudiantes internacionales y extranjeros/as: migrantes en una universidad pública argentina. En: Pedone C. Gómez Martín C. (eds.). Los rostros de la migración cualificada: estudios interseccionales en América Latina (pp. 155-188). Clacso. [ Links ]

Martínez Pizarro J. 2010. Migración calificada y crisis: una relación inexplorada en los países de origen. Migración y Desarrollo, 7(15), 129-154. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=66019856004 [ Links ]

Novaro G. 2011. Niños migrantes y escuela: ¿identidades y saberes en disputa?. En: Novaro G. (eds.). La interculturalidad en debate. Experiencias formativas y procesos de identificación en niños indígenas y migrantes (pp. 179-204). Biblos. [ Links ]

Instituto Internacional de la Unesco para la Educación Superior en América Latina y el Caribe (IESALC) 2008. Declaración y plan de acción de la Conferencia Regional de la Educación Superior en América Latina y el Caribe (CRES 2008). UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000181453 [ Links ]

Oso L. Dalle P. Boniolo P. 2019. Movilidad social de familias gallegas en Buenos Aires pertenecientes a la última corriente migratoria: estrategias y trayectorias. Papers. Revista de Sociología, 104(2), 149-155. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers.2573 [ Links ]

Panaia M. 2009. Demandas empresarias en las estrategias de formación de los ingenieros en dos zonas argentinas. En: Neffa J. De la Garza E. Muñiz Terra L. (eds.). Trabajo, empleo, calificaciones laborales e identidades laborales (pp. 243-272). Clacso. [ Links ]

Parra-Sandoval M. C. 2022. Internacionalización de la educación superior: lo que subyace en el discurso de UNESCO y OCDE. Revista Internacional de Educação Superior, 8, 1-17. http://educa.fcc.org.br/pdf/riesup/v8/en_2446-9424-riesup-8-e022013.pdf [ Links ]

Pedone C. Alfaro Y. 2015. Migración cualificada y políticas públicas en América del Sur: el programa PROMETEO como estudio de caso. Forum Sociológico, 27, 31-42. https://doi.org/10.4000/sociologico.1326 [ Links ]

Pérez P. Busso M. 2015. Los jóvenes argentinos y sus trayectorias laborales inestables: Mitos y realidades. Trabajo y Sociedad, 24, 147-160. http://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/tys/n24/n24a08.pdf [ Links ]

Piñeros Lizarazo R. Maduro Silva D. B. 2020. Migración académica Sur-Sur en la educación superior latinoamericana en el siglo XXI. Paideia Surcolombiana, 25, 181-183. https://doi.org/10.25054/01240307.2854 [ Links ]

Prosecretaría de Relaciones Internacionales (PRI-UNC) 2019. Base de datos sobre movilidad saliente de la PRI-UNC (2006-2019) [Unpublished data set] Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. [ Links ]

Ramírez R. 2010. Transformar la universidad para transformar la sociedad. Senplades. [ Links ]

Ruta C. 2015. El futuro de la universidad argentina. En: Tedesco J. C. (eds.). La educación argentina hoy: la urgencia del largo plazo (pp. 319-350). Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Sander J. Gonzalez A. Trujillo E. Gonzalez M. Debandi N. Hendel V. 2021. Población migrante adulta y acceso al sistema educativo. En: Debandi N. Nicolao J. Penchaszadeh A. (eds.). Anuario Estadístico Migratorio de la Argentina 2020 (pp. 111-119). Red de Investigaciones en Derechos Humanos-CONICET; Encuesta Nacional Migrante de Argentina. [ Links ]

Sassen S. 2007. Una sociología de la globalización. Katz. [ Links ]

Sosa M. 2016. Migrantes en el sistema educativo argentino. Un estudio sobre la presencia de alumnos extranjeros en los estudios de nivel superior. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 7(19), 97-116. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.20072872e.2016.19.189 [ Links ]

Trabalón C. 2022. Proyectos migratorios, educación y control estatal: jóvenes haitianxs en Argentina en tiempos de “cambio”. En: Handerson J. Cédric A. (eds.). El sistema migratorio haitiano en América del Sur: proyectos, movilidades y políticas migratorias (pp. 359-392). Clacso. [ Links ]

Trejo Peña A. Suárez Bequir S. 2018. Estudiantado mexicano de posgrado en España: motivaciones y mecanismos impulsores detrás de la movilidad estudiantil. Periplos, 2(1), 36-50. https://www.periodicos.unb.br/index.php/obmigra_periplos/article/view/21225 [ Links ]

UNESCO 8 de julio de 2021. Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students. http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow#slideoutmenu [ Links ]

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (UNC) 2019. Anuario Estadístico 2018. Área de Estadística e Indicadores Institucionales. [ Links ]

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (UNC) 10 de septiembre de 2020. Resolución rectoral del Honorable Consejo Superior (núm. RR-2020-887-E-UNC-REC). https://archivo.fcc.unc.edu.ar/sites/default/files/archivos/estudiantes_extranjeros_rs-2020-00150632-unc-rec.pdf [ Links ]

Villanueva E. 2017. La universidad ayer y hoy: perspectivas. En: Filmus D. (eds.). Educar para el mercado (pp. 131-178). Octubre. [ Links ]

Wagner A. C. 2007. Les classes sociales dans la mondialisation. La Découverte. https://doi.org/10.3917/idee.153.0078 [ Links ]

1 The imperative of mobility consists of the obtainment for degrees in prestigious academic centers through short stays or the completion of higher studies, with the expectation of achieving better job positions that reward such added value (Gómez & Vega, 2018).

2 Aimed at “developing and intensifying relations between their peoples, so that they better understand each other and acquire a more precise and true knowledge of their respective ways of living” (UNESCO, 2018, cited in Parra-Sandoval, 2022, p. 9)

3 By this it is referred to the payment of any additional fees, exam fees, and registration fees by students at public universities, elements that undermine the intended-free nature of the system and thus restrict access.

4 It should be taken into account that UNC only provides electronic certificates to the Immigration Directorate once the interested student has met all the enrollment requirements and is an active student. For specific studies on the impact of the educational and migratory journey of non-MERCOSUR students, see Trabalón (2022).

5 This study will not delve into the inbound dynamics of the categories set by the sources consulted in terms of immigrant, foreigner, international, or the possible overlaps when accounted for by country of origin, and when categorized as Argentinian by choice and naturalized. At this stage of the study, the focus was on observing, based on the available data, certain conditioning factors recorded by the UNC statistics system, although it is expected for this review to be furthered in future works.

6 To acquire citizenship by naturalization, one must be of legal age (18 years old), have lived in Argentina for two uninterrupted years, certified by the National Immigration Directorate (except if one married a native citizen and/or has a son born in the country). Meanwhile, Argentinians by choice are those who were born abroad and can choose to naturalize due to having an Argentinian mother or father.

7 The survey was carried out between 2019-2020 through a servicio tecnológico de alto nivel (STAN) (high-level technological service), led by Jiménez Zunino. The PRI-UNC was supported in the processes of preparation, dissemination, and analysis of the survey data, and it facilitated access to the database of the different internationalization programs. Within the framework of this collaboration, interviews were conducted with managers of the organization. The survey includes 239 cases of 1 403 young people (aged 25 to 35) who carried out outbound mobility between 2006 and 2019.

8 In the qualitative work that is in progress, subsequent emigrations of outgoing students have been detected. In some cases, these students were stranded abroad due to the COVID-19 pandemic; in others, they had previous migration projects that were completed during the years 2020 and 2021.

9 Another dimension providing clues on social origins is the type of secondary school the respondents attended: mostly private (58%) and secular (67%) secondary level institutions.

Received: November 28, 2022; Accepted: August 14, 2023

texto en

texto en