Introduction

The radiographic control of the endodontic post-treatment is used to observe the healing of the periapical injuries. When the treatment fails, the tooth continues showing radiographic signs and in some cases the complications can produce pain (Hargreaves & Berman, 2016).

The periapical disease is an acute or chronic inflammation of the periapical tissue, it is produced in 90% of the cases as a result of dental cavities but also as a result of dental procedures, impacts or injuries, teeth grinding and abrasion (Saatchi, 2007; Segura-Egea, et al., 2015).

Chronic apical periodontitis is a consequence of the pulp necrosis where the inflammation hurts and causes pain to percussion, and in some cases reveal radiographic changes. Chronic apical periodontitis is asymptomatic and radiographically reveals a periradicular radiolucency (Hargreaves & Berman, 2016; Sigurdsson, 2003).

The radiographically observable periapical or periradicular osteolytic injuries are a consequence of the osseous destruction carried by the periapical and periradicular inflammation process (Ridao-Sacie et al., 2007; Saatchi, 2007). On its unbalanced stage, it is possible to disperse the infection and inflammation to closer tissues and this can be considered as a severe inflammation but fortunately, this is a rare condition (Hargreaves & Berman, 2016). The principal way to heal injuries is by reparation of tissues. Repairing is a biological process where the continuity of the tissue is established by the formation of a new tissue but it does not restore the anatomy and original function (Altare, 2010).

The main objective of the endodontic treatment is to set the conditions for the repair of the damaged periapical tissues, once the causes of the aggression are eliminated, the reaction evolves the repair process where the proliferation and differentiation of specific cells work in the reposition of destroyed tissues (Soares & Goldberg, 2012; Hargreaves & Berman, 2016).

The success of the endodontic treatment can be affected by four factors in a positive or negative way: 1) the presence or absence of apical periodontitis, 2) the apical density, 3) apical extension of the radicular obturation, and 4) the quality of the final restoration. It has been observed that teeth with previous endodontic treatment without a final restoration or with poorly adjusted treatment shows the worst periapical healing (Haapasalo et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2011; Kirkevang et al., 2014).

The healing process takes between six months and several years (approximately 4 years). In some cases, the size of periapical lesions can persist, can reduce, can increase or show no changes (Haapasalo et al., 2011; Peters & Peters, 2013).

Endodontic literature proposes to evaluate the success of a treatment by means of clinical and radiographical criteria. The clinical success is when the patient does not experiment pain in the dental piece treated by the dentist; nevertheless, this can be misleading because a chronic periapical asymptomatic injury might occur. Radiographic success is characterized by the disappearance of the radiographic sign of periapical lesion after the root canal treatment (Hilú & Balandrano-Pinal, 2009). The European Society of Endodontics recommends a follow-up visit for four years (Lynch & Burke, 2006).

A 63% of cases of teeth with periapical lesions show a considerable reduction after the second year after the endodontic treatment, therefore, a retreatment is not considered. It is important to consider following the changes of the radiolucency in the teeth with periapical lesions after two years or more of being treated (Zhang et al., 2015).

Due to the periapical healing can be radiographically observable one year after endodontic treatment, the main objective of this study is to determine the characteristics in radiographic healing after one year of the treatment. The study was performed on patients who attended the follow-up sessions after one year of treatment through the Periapical Index (PAI) (Orstavik et al., 1986).

Method

This study was performed on patients in the Postgrade Endodontics Area, School of Dentistry at the Autonomous University of Yucatan that showed radiography observable periradicular injuries at the beginning of the treatment, maintained a schedule of follow-up sessions after one year of the treatment and accepted to participate in the study as indicated in the "World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki" (Hurts, 2014); all the patients agreed to participate in the study verbally and then, they sign a letter of informed consent. The inclusion criteria were to have a radiographically observable endodontic pathology and to accept to continue one year follow-up. The exclusion criteria were health systematic compromise presence. The elimination criteria were applied when the patients do not return to the follow-up session. During the first visit at the clinic, an endodontic diagnostic test was performed by a postgraduate student through clinical and radiographic assessment to establish the treatment plan for each case according to the postgraduate of endodontic protocol. The clinical test was based on the observation of periodontal tissues, percussion, palpation, mobility and periodontal probing. An XCP was used in all the follow-up sessions to take digital periapical X-Rays, using periapical long cone paralleling technique to estandarize the radiographic images. We also conducted anamnesis to obtain epidemiological data and evaluate the presence of other systemic and local factors. All patients were appointed 3, 6 and 9 months to determine the presence of any symptomatology and the restauration quality. And a one year follow-up session was performed in order to finish their clinical and radiographical control according to the postgraduate of endodontic protocol to discharge the patient. In the final follow-up session (one year), the teeth were clinically and radiographically analyzed to confirm systemic diseases, quality of treatment and the presence or absence of definitive restoration.

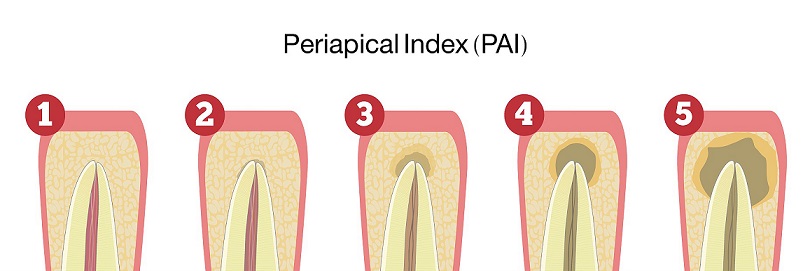

Digital periapical radiographies were recorded an analyzed using PAI (Orstavik et al., 1986) and the classification of the endodontic pathologies used, was the one described by Sigurdsson (Sigurdsson, 2003). Periapical Index (PAI) is a measurement system which is modified and applied to comparative epidemiological and clinical studies. This system provides with an ordinary scale of five punctuations that go from "Normal Periapical Structure" to "Severe Periodontitis with exacerbating features" and is based on a study of histological and radiographical correlation of Brynolf. It was described for the first time by Orstavik in 1986 (Orstavik et al., 1986).

The scales of PAI are as follow: 1. Normal periapical structure, 2. Small changes in bone structures, 3. Changes in bone structure with mineral loss 4. Periodontitis with well-defined radiolucent area, and 5. Severe periodontitis with exacerbating features (Orstavik et al., 1986) see Figure 1.

The evaluation was made independently by two endodontic experts that were previously calibrated. The agreement between the observers was 89.74%. The four cases with disagreement were analyzed by a third endodontic expert independently. The final score for that four cases was recorded according to the agreement between the third observer and one of the original observers. Data collected was organized in an Excel( data base and percentages and graphics were calculated afterwards, the T Student test for paired data was used to observe differences between the initial and final scores. The distribution of the sample was normal.

Results

Endodontic diagnosis were performed to a total of 395 teeth, and its endodontic treatment during the study period and we could find that 87 (22.02%) presented radiographically visible periapical lesions at the sixth month follow-up session and 40 (45.97%) of those 87 patients came back to the one year follow-up sessions.

Distribution of periapical pathologies is as follows: 2 (5%) showed apical periodontitis with abscess, 6 (15%) showed apical periodontitis with sinuous tract, 10 (25%) showed acute apical periodontitis and 22 (55%) showed chronic apical periodontitis.

One tooth showed a vertical fracture in the sixth month follow-up session due to the absence of definitive restoration and it was eliminated of the research; 38 of the 39 patients (97.43%) showed evident radiographic healing; one (2.56%) remained with no radiographic change, however asymptomatic, for that reason, the frequency of observable radiographic healing after one year was 97.43%, see Figure 2.

After one year of the endodontic treatment, we observed a decrease of the two cases with apical periodontitis with abscess. One lesion healed completely from PAI 3 to 1 and the other from PAI 4 to 2. In the six cases of periapical periodontitis with sinuous tract, we observed a healing of 100% of the cases passing from PAI 3 to 1. In ten cases with severe apical periodontitis we obtained an initial PAI 3 in six cases and a PAI 5 in 4 cases; after one year those that started in PAI 3, four healed to PAI 1 and two to PAI 2; and the cases of PAI 5, three healed to a PAI 2 and one healed to a PAI 3.

In the twenty one cases with chronic apical periodontitis, eleven cases showed a PAI 3 and nine cases showed a PAI 4, after a year of treatment the cases that started in PAI 3 changed to PAI 1 and one case showed no changes; the nine cases with PAI 4 changed to PAI 2.

After one year, the healing index of all radiographic observable lesions was 97.43% where 53.84% was a complete healing and 43.58% was partial healing. Thirty three of the cases (84.61% lowered two levels in the PAI index scale, 3 (7.69%) three levels, 2 (5.12%) one level and 1 (2.56%) showed no changes. The distribution of the sample was normal, so we used the T Student test for the paired data. The score threw a statistics difference between the initial and final score t=25.372 with 38 d.f., p=0.000. The mean of PAI at the endodontic treatment was 3.74 with a s.d. of 0.97. The mean after one year finished the treatment was 1.77 with a s.d. of 0.90. The difference between the mean in the initial and final evaluations was 1.97 with a s.d. of 0.49; thus, after a year we could observe a reduction of two levels.

It was also found that three patients showed vertical root fractures before the six months treatments because of the lack of rehabilitation and just one patient go to the six month control visit but the patient was eliminated from the study because of the absence of coronal sealing and vertical root fracture.

Discussion

In endodontics, it is important to have follow-up sessions, but in the first months after treatment, it is difficult to observe evidence of periapical lesions healing. In this study, the frequency of observable radiographic healing after one year was 97.43%.

According to the PAI, the results of the present study showed 43.58% partial healing and 53.84% complete healing. There are many studies with different follow-up sessions protocol to evaluate the success of the endodontic treatment using periods of time between six months and several years (Haapasalo et al., 2011; Peters & Peters, 2013; Zhang et al., 2015). It is remarcable that of the entire sample, 84.61% showed a two-level decrease from their initial PAI index stage. So, we found in this study, that one year was enough to see significative radiographical changes in the healing of chronical pathologies.

Although many studies refer to the need for long-term follow-up in cases of periapical lesions, the results of the present study (two stages of improvement of the PAI), they can be applied in clinical practice as indicators of a healing process in progress.

In the present study, 22.02% of the endodontic patients had visible periapical lesion as expected, since most studies report similar data. In a research performed by Becconsall-Ryan et al. 2010, it presented that 29.2% of the total population showed radiographically observable periapical lesions, and Davies et al. 2016 presented that 55 patients (20%) out of 273 showed periapical lesions. (Timmerman et al., 2017) also described that 179 (25.8%) out of 695 patients who were treated with panoramic radiographs showed periapical lesions which is comparable with this study since the total is of the patients with periapical lesions is 22.02%.

Peters et al. (2011) obtained, of a total of 178 patients tested with panoramic radiographs that 93 (52.24%) cases showed periapical lesions which differs from the previous studies and ours because it is based in the methodology of Cleen et al. (1993) that considers a periapical lesion to any widening of the periodontal ligament that doubles the size of it, but this kind of lesion can be considered in the PAI 2 which is not a periapical lesion. Also, the panoramic radiograph does not show an accuracy comparable to a periapical radiograph.

Timmerman et al. (2017) described that 11 (45.88%) out of 24 cases had a PAI 3, 9 (37.5%) showed a PAI 4, and 4 cases (16.66%) showed a PAI 5; Tsesis et al. found that in a research of 200 teeth with periapical injuries, 88 (44%) showed a PAI 3, 22 (11%) a PAI 2, and 2 cases (1%) a PAI 5. These distributions of the frequency of PAI index are comparable to this research because of a total of 39 cases, during the radiographic initial evaluation, it was found that 24 (61.5%) showed a PAI 3, 11 (28.2%) a PAI 4 and 4 cases (10.25%) a PAI 5.

Huumonen & Ørstavik (2013) obtained in their study that the teeth with an initial PAI from 3 to 5 showed a meaningful improvement in the first 3 months, 27% were considered healthy reaching a PAI 1 or 2; healing during the first year of groups with PAI 4 and 5 were slower than the patients with a PAI 3. Monardes et al. (2016) obtained from a total of 227 cases, that 213 (93.8%) reached a clinic and radiographic success and 14 (6.2%) failed, these results are similar to the results of our research since we also obtained a decrease in the lesions of two levels in the PAI after one year of control.

In the present study, 38 (97.43%) of the cases with an initial visible periapical lesion showed a periapical healing observed radiographically after one year of treatment this may be due to the standardization level in the treatments performed by the students in the Postgrade Endodontic Area at the Autonomous University of Yucatan. Timmerman et al. (2017) performed an endodontic treatment in 54 patients and found that six (11.1%) cases did not show periapical lesions in their subsequent visits and 25 (46%) remained with no changes which differ from this research because from a total of 39 cases it was found that 21 cases (53.48%) did not show periapical lesions in their subsequent visit; however, 17 (43.58%) showed a reduction in their injuries and just 1 case (2.56%) showed no changes; the difference in this studies might be because Timmerman et al. (2017) used panoramic radiographs in his research and this could reduce the clarity of the images which can lead to having a poor observation of the radiographic changes.

In the research of Peralta-Lazo et al. (2017) found an endodontic success rate of 98% in 52 teeth after the six-month visit and the remaining 2% was a questionable case (showed no change but was asymptomatic) and one failure caused by a fracture because of the lack of rehabilitation. This research also showed similar numbers since we obtained that six patients (15%) had no restoration after six months of the treatment and one case was considered as a failure because showed a vertical root fracture, however, we obtained a high percentage of radiographic success. The occurrence of root fracture is quite similar to the 5% recently reported by Pirani et al. (2018).

Timmerman et al. (2017) described that from 54 endodontic treatment cases that showed periapical lesions in their first control visit with panoramic radiographs, twenty one (38.9%) did not show coronal restoration in subsequent evaluations, of which, just one case (4.8%) did not show a subsequent periapical lesion, which is important to emphasize because we also found in this research that from 395 endodontic cases, 107 (27.08%) did not show coronal restoration (3 showed vertical root fractures at 6 months before the initial treatment) added to 154 (39.98%) patients who did not show to their control visit that lead us to the idea that we have to emphasize more with patients to rehabilitate their teeth to have a better success rate in their treatment. It is really difficult to achieve patients again for the follow-up sessions. Despite all efforts to explain the importance, we could not do it for a large sample size.

The particular case that showed no radiographic change was a healthy patient whose endodontic treatment presented an endodontic overextension. Pirani et al. 2018 have reported the healing outcome was not impacted by the extrusion of the root filling, whereas Ng et al. 2011 have reported an adverse impact. So, the impact of root filling extrusion on the prognosis of apical periodontitis has not yet been definitively clarified (Hargreaves & Berman 2016). The case that was eliminated corresponded to a diabetic patient with no rehabilitation, however, the failure was because of the lack of rehabilitation which leads to a vertical root fracture.

Conclusion

The cases in which a periapical healing was observed radiographically after one year of treatment was 97.43%.

The index of periapical healing of the lesions, after one year exhibited that 43.58% of the cases showed partial healing and a 53.84% showed complete healing.

Of all cases, 84.61% showed a two-level decrease from their initial PAI index stage.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)