Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.5 spe 8 Texcoco 2014

Investigation notes

Accelerated aging on the quality of maize seeds for alternative sprouted fodder production

1División de Estudios de Posgrado- Instituto Tecnológico de Conkal km 16.3 antigua carretera Mérida-Motul, Conkal, C. P. 97345 Yucatán, México. (daniel5366@hotmail.com; lizette_borges@hotmail.com; lpinlo@yahoo.com.mx; mmagana@itaconkal.edu.mx; rsangines@itaconkal.edu.mx).

2Departamento de Producción Vegetal-Universidad de Almería. 04120 Almería, España. (mgavilan@ual.es).

The maize seed of good quality is strategic input to produce sprouts as an alternative fodder for animal feed especially in times of drought and prolonged storage, leading to loss of germinability and vigor according to genotype and environment. The study was conducted at the Conkal Institute of Technology in July 2011, accelerated aging was applied to three maize cultivars (País Tuxpeño, X'nuuknal and Sinaloa) for 24 and 48 h at 45 °C assuming 85 to 100% relative humidity in order to evaluate its effect on maize seedling germination and development in greenhouse, planting was in plastic trays with bovine manure as substrate. The evaluated variables: initial seed weight, average number of days to total germination, germination percentage, plant height, total fresh and dry weight, total leaf area, fresh and dry weight of root and shoot and shoot: root ratio. The experimental design was randomized complete blocks with 3 x 3 factorial arrangement with (n= 5) and Tukey means comparison (p< 0.05). The results showed significant differences between maize cultivars in all variables whereas the effect of accelerated aging times and the interaction of both showed significant differences only in germination percentage. The País Tuxpeño maize was more favorable to produce green forage for its viability and resistance to deterioration.

Keywords: deterioration; green fodder; substrate; viability

La semilla de maíz de buena calidad es insumo estratégico para producir germinados como forraje alternativo para alimentación animal sobre todo en época de sequía y el almacenamiento prolongado conduce a pérdidas de germinabilidad y vigor en función del genotipo y ambiente. El estudio se desarrolló en el Instituto Tecnológico de Conkal en julio de 2011, el envejecimiento acelerado se aplicó a tres materiales de maíz (País tuxpeño, Xnuuknal y Sinaloa) durante 24 y 48 h a 45 °C asumiendo 85 a100% de humedad relativa con el objetivo de evaluar su efecto en germinación y desarrollo de plántulas de maíz, en invernadero la siembra fue en bandejas de plástico con estiércol de bovino como sustrato. Las variables evaluadas: peso inicial semillas, número medio de días a germinación total, porcentaje de germinación, altura de planta, peso fresco y seco total, área foliar total, peso fresco y seco de la raíz y vástago y la relación vástago: raíz. El diseño experimental fue bloques completos al azar con arreglo factorial 3 x 3 con (n= 5) y comparación de medias Tukey (p< 0.05). Los resultados mostraron diferencias significativas entre materiales de maíz en todas las variables mientras que el efecto de tiempos de envejecimiento acelerado y la interacción de ambos únicamente mostraron diferencias significativas en porcentaje de germinación. El maíz País Tuxpeño por su viabilidad y resistencia al deterioro resultó el más favorable para producir forraje verde.

Palabras claves: deterioro; forraje verde; sustrato; viabilidad

The production of sprouted maize is an important alternative forage source for animal feed especially in times of drought, and seed quality is strategic to increase the total fresh weight. Seed quality involves the integrity of physiological structures and processes for preserving viability (Vitoria, 2007). Indicators of this are: germination and vigor, depending on the genotype and production and post- harvest management. (Flores, 2004; Salazar et al., 2006).

Accelerated aging deteriorates the seed and equals the natural process, it is the vigor test most applied to commercial seed (Vashisth, 2009; Durán et al, 2011) by exposure to high temperatures and humidity (Barros and Filho, 2003) undermine their germination capacity, seedling early growth, tolerance to adverse conditions and does not occur uniformly in seeds, even in the same batch (McDonald, 1999). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of accelerated aging on viability, development and growth of seedlings of three maize materials to produce sprouts as alternative fodder.

The experiment was carried out at the Conkal Institute of Technology, Yucatán in July 2011. Three maize materials produced and available in Yucatán were used, two types of Tuxpeño race, the País Tuxpeño (PT) and X'nuuknal (X) harvested and stored in rustic barns at 28 °C room temperature and 85% relative humidity in July 2011 and the third maize material is brought from Sinaloa (S) in raffia bags at 28 °C room temperature, in practice the three maize materials are used in sprouts production for fresh fodder.

The moisture content in País Tuxpeño is 11%, Xnuuknal 10.39% and Sinaloa 10%. Accelerated aging was induced in lots of 25 seeds, for this purpose they were wrapped with tent cloth held with a cotton thread 1 cm from the level of distilled water, 2 L added to the 4 L beaker, sealed with parafilm paper and aluminum assuming 85 to 100% relative humidity, three treatments were applied for seed deterioration: 1) zero time and ambient temperature of 26 °C as a check ; 2) time of 24 h at a constant temperature of 45 °C; and 3) time of 48 h at constant temperature of 45 °C (Salazar et al, 2006, Villaroel and Méndez-Natera 2007). A randomized block design was used with 3 x 3 factorial arrangement with (n= 5), the first factor was time 0, 24 and 48 h and the second factor was three maize materials País Tuxpeño, X'nuuknaal and Sinaloa.

Germination , growth and development of maize seedlings was conducted in greenhouse, acceleratedly aged maize seeds were placed in plastic trays of 0.242 m2 with bovine manure as substrate which contained 2.24, 0.31 and 0.47% of N, P, K respectively. The germination and development variables were: initial seed weight (ISW), germination percentage (GP), average number of days to total germination (DTG), seedling height (SH), total fresh weight (TFW), total dry weight (TDW), total leaf area (TLA), fresh and dry root and shoot weight (RFW, SFW, RDW, and SDW) respectively and shoot: root ratio (S: R). The analysis of the evaluated variables and Tukey means comparison test (p< 0.05) were performed using the Statistica Six Sigma software.

The initial weight of País Tuxpeño, X'nuuknal and Sinaloa showed significant differences (p< 0.05). The highest value of 8.5 g was observed in the Sinaloa maize while País Tuxpeño and X'nuuknal showed lower values of 7.1 and 6.9 g Figure 1.

Figure 1 Initial weight of maize seed before accelerated aging. Means with the same superscript are statistically equal.

The analysis of variables by effect of the application of accelerated aging according to the maize materials factor showed significant differences while the effect of accelerated aging times and the interaction showed significant differences only in germination percentage, this trend has been reported Salazar et al. (2006) who reported that maize seed quality is directly related to the increase of the accelerated aging time, decreasing the germination percentage thereof.

In this regard, the Pais Tuxpeño maize cheek showed high germination and the 24 and 48 h of accelerated aging treatments showed low germination; according to Delouche and Caldewel (1960) the germination percentage alone cannot be considered an adequate vigor index while Aristizábal and Alvarez, 2006 indicate that seeds over 80% germination after accelerated aging could be classified as high vigor, from 60-80% average vigor, and under 60% as low vigor.

By analyzing the time factor in Figure 2A significant differences were found in the GP. The Tukey test (p< 0.05) showed that the 0 h cheek had the highest GP of 81% compared to the 24 and 48 h aging times with 71 and 70%, which were statistically equal but below the 80% GP required to produce sprouts. For time by material interaction in Figure 2B different behaviors were observed for the loss of germination over accelerated aging time in each maize type, País Tuxpeño showing the best GP without statistical differences in the three times, while the Sinaloa showed the lowest scores (p< 0.05).

Figure 2 A) Effect of the three accelerated aging times; and B) interaction maize and accelerated aging time on the germination percentage of País Tuxpeño, X'nuuknal and Sinaloa. Means with the same superscripts are statistically equal.

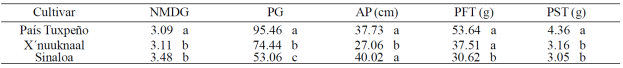

Among the País Tuxpeño, X'nuuknal and Sinaloa maize cultivars significant differences were observed in the mean number of days to total germination, germination percentage, plant height, total fresh weight and total dry weight (p< 0.05). According to Aristazábal and Alvarez (2006) these responses are due to the particular genetic composition of each cultivar, Table 1.

Table 1 Average number of days to total germination DTG, germination percentage GP, plant height PH, total fresh weight TFW and total dry weight TDW in País Tuxpeño, X'nuuknal and Sinaloa maize under three aging times 0, 24 and 48 h. Means with the same superscripts are statistically equal.

Although there was no significant effect of accelerated aging time as simple factor in the average number of days to total germination, a result consistent with Villarroel and Méndez (2007) significant differences were found between materials for the same variable in País Tuxpeño and X'nuuknaal. The GP between maize materials obtained significant differences País Tuxpeño showed the highest germination percentage with 95% and Sinaloa the lowest with 53%. It is likely that the aging conditions with moist heat cause malfunction of the metabolic events involved in germination, suggesting that stimulation of root sprouts is a physical event promoted by rehydrating the seminal tissues (Bewley and Black, 1994).

Although no significant differences were found in height by the simple factor of accelerated aging time, the material factor showed significant differences, the greatest height was in País Tuxpeño 37 cm and Sinaloa 40 cm which coincides with Laynez et al. (2007) who reported greater height on seedlings from maize seeds with medium and higher weight.

The best TFW value was obtained with seeds of lower ISW in País Tuxpeño and X'nuuknaal 53 and 37 g at12 days after planting (DAP). According to Müller et al. (2005) 1 kg of maize produces 9 kg of TFW. It was estimated that 1 kg of País Tuxpeño maize produces 8.5 kg of TFW, this same cultivar had the highest TDW while X'nuuknaal and Sinaloa were lower, both without significant statistical differences.

The total leaf area TLA revealed significant differences (p< 0.05) between maize materials, the effect of accelerated aging times and the interaction of time by maize cultivars was not significant. The TLA of País Tuxpeño, X'nuuknal and Sinaloa was 44.9, 38.8 and 25.5 cm2.

Although the effect of accelerated aging time and the interaction time by maize materials obtained no significant effects, the RFW, SFW, TFW, RDW, SD

W and TDW variables differed significantly (p< 0.05) only between maize cultivars. The greatest TFW value corresponded to the best S: R ratio of País Tuxpeño and X'nuuknal while Sinaloa was lower in both eases, Figure 3A. The total dry weight showed no significant differences between maize cultivars, while the S: R ratio did show significant differences between the three materials. The highest S: R ratio was X'nuuknal 1.85, País Tuxpeño 1.33 and Sinaloa 0.70, Figure 3B.

Figure 3 A) Total fresh weight and its shoot: root ratio S: R; and B) total dry weight and its shoot: root ratio S: R, País Tuxpeño PT, X'nuuknal X and Sinaloa S, under accelerated aging. Means with the same superscript are statistically equal.

From the three maize materials under accelerated aging, País Tuxpeño retained the best performance capacity in viability, growth, seedling development and total fresh and dry weight production, its seed was able to withstand exposure to deterioration for 24 and 48 h while X'nuuknal and Sinaloa cultivars did not keep their performance capacity and their seeds were less resistant when exposed to deterioration, allowing discrimination of both seeds and the indication that the País Tuxpeño maize retained the quality required to produce sprouts for green forage.

Literatura citada

Aristizábal, L. M. y Álvarez, L. P. 2006. Los efectos del nivel de vigor de la semilla pueden persistir e influenciar el crecimiento de la planta, la uniformidad de la plantación y la productividad. Agronomía. 14(1):17-24. [ Links ]

Barros, T. S. and Filho, J. M. 2003. Accelerated aging of melon seeds. Scientia Agricola. 60(1):77-82. [ Links ]

Bewley, J. D. and Black, M. 1994. Seeds: physiology of development and germination. 2ed. Plenum Press, New York. 445 p. [ Links ]

Delouche, J. C. and Caldwell, P. W. 1960. Seed vigor and vigor tests. Proceedings of the Association of Official Seed Analysts. 50(1):136-140. [ Links ]

Durán, H. D.; Gutiérrez, H. G.; Arellano, V. J.; García, R. E. y Virgen, V. J. 2011. Caracterización molecular y germinación de semillas de maíces criollos azules con envejecimiento acelerado. Agron. Mesoam. 22(1):11-20. [ Links ]

Flores, H. A. 2004. Introducción a la tecnología de las semillas. Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo (UACH). Primera Edición, Chapingo-Estado de México. 61-76 pp. [ Links ]

Laynez, G.; Méndez, N. y Mays, T. 2007. Crecimiento de plántulas a partir de tres tamaños de semilla de dos cultivares de maíz (Zea mays L.), sembrados en arena y regados con tres soluciones somáticas de sacarosa. IDESIA. 25(1):21-36. [ Links ]

McDonald, M. B. 1999. Seed deterioration: physiology, repair, and assessment. Seed Sci. Technol. 27:177-237. [ Links ]

Müller, L.; Manfron, P.; Santos, O.; Medeiros, S.; Haut, V.; Dourado, D.; Binotto, E. y Bandeira, A. 2005. Producción y composición bromatológica de forraje hidropónico de maíz (Zea mays L.) con diferentes densidades de siembra y días de cosecha. Zootecnia Tropical. 23(2):105-119. [ Links ]

Salazar, P.; Trejo, A. y Hernández, L. M. 2006. Pruebas de envejecimiento acelerado en semillas de maíz (Zea mays L.) de diferentes bases genéticas. Rev. Unellez Cienc. Tecnol. 24:63-69. [ Links ]

Vashisth, A. 2009. Germination characteristics of seeds of maize (Zea mays L.) exposed to magnetic fields under accelerated ageing conditions. J. Agric. Physics. 9:55-58. [ Links ]

Villaroel, N. y Méndez, N. 2007. Calidad de semilla de nueve lotes de diferentes cultivares de maíz (Zea mays L.) afectada por el envejecimiento acelerado. Revista de la Facultad de Agronomía de La Universidad del Zulia. 24(1):89-94. [ Links ]

Vitoria, H. 2007 Relación de la calidad fisiológica de semillas de maíz con pH y conductividad eléctrica. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. 39(2):91-100. [ Links ]

Received: March 2014; Accepted: April 2014

texto en

texto en