Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.14 no.78 México jul./ago. 2023 Epub 14-Sep-2023

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v14i78.1386

Scientific article

Diversity of medium-sized and large mammals of Las Margaritas Experimental Station, Northeastern Sierra of Puebla

1Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Campo Experimental San Martinito. México.

2Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Sitio Experimental Tlaxcala. México.

3Prestador de servicios técnicos. Solórzano Hueytamalco. México.

4Prestador de servicios técnicos. Tételes de Ávila Castillo. México.

Tropical ecosystems are home to a wide diversity of medium-sized and large mammals. The objective of this research was to estimate the species diversity of medium-sized and large mammals by photo-trapping in the high grass and Evergreen tropical rain forest of the Las Margaritas Experimental Site, located in the Northeastern Sierra of Puebla. Two vegetation areas with different degrees of recovery were sampled: secondary vegetation (high grass) and Evergreen tropical rain forest. The richness, abundance, and alpha and beta diversity of medium-sized and large mammals were estimated. Nineteen species of wild mammals belonging to six orders and 10 families were recorded; the most abundant species were Nasua narica, Didelphis marsupialis, and Dasypus novemcinctus; Herpailurus yagouaroundi, Potos flavus, Puma concolor, Leopardus wiedii, Urocyon cinereoargenteus, and Conepatus leuconotus were the least abundant. The high grass and the Evergreen tropical rain forest presented a proportional richness and alpha diversity with values of H´=2.04 and 2.11, the Pielou index was J’=0.94 y 0.89, Simpson's index had values of

Key words Tropical forest; alpha diversity; beta diversity; mammals; species richness; secondary vegetation

Los ecosistemas tropicales albergan una amplia diversidad de mamíferos medianos y grandes. El objetivo de esta investigación fue estimar la diversidad de especies de mamíferos medianos y grandes mediante fototrampeo en acahuales y Selva alta perennifolia del Sitio Experimental Las Margaritas, ubicado en la Sierra Nororiental de Puebla. Se muestrearon dos áreas de vegetación con diferentes grados de recuperación: vegetación secundaria (acahual) y Selva alta perennifolia. Se estimaron riqueza, abundancia, y diversidad alfa y beta de mamíferos medianos y grandes. Se registraron 19 especies de mamíferos silvestres pertenecientes a seis órdenes y 10 familias; las especies más abundantes fueron Nasua narica, Didelphis marsupialis y Dasypus novemcinctus, mientras que Herpailurus yagouaroundi, Potos flavus, Puma concolor, Leopardus wiedii, Urocyon cinereoargenteus y Conepatus leuconotus registraron la menor abundancia. El acahual y la Selva alta perennifolia presentaron una riqueza proporcional y una diversidad alfa con valores de H´=2.04 y 2.11, el Índice de Pielou fue de J’=0.94 y 0.89, el índice de Simpson tuvo valores de

Palabras clave Bosque tropical; diversidad alfa; diversidad beta; mamíferos; riqueza de especies; vegetación secundaria

Introduction

Wildlife conservation is going through difficult times, particularly for medium-sized and large mammals; its permanence and stability is constantly threatened by poaching and land use change (Gallina and González-Romero, 2018). The tropical ecosystems are the most affected, and it is estimated that the annual rate of land use change varies between 0.7 % and 4.5 % in the Gulf of Mexico area (Leija et al., 2021). In these habitats, wild mammals are an essential element that regulates plant populations through herbivory, seed dispersal, and predation, which help to keep ecosystem populations in balance (Mezhua-Velázquez et al., 2022). Fragmentation also limits the connectivity between ecosystems, as it disrupts the movement of mammal species that require large wildlife areas (Ruiz-Gutiérrez et al., 2020).

Recent studies show the importance of continuous research on mammals through wildlife inventories (Pérez-Solano et al., 2018; Serna-Lagunes et al., 2019; Salazar-Ortiz et al., 2020). These allow knowing which and how many taxa coexist in a given ecosystem or area (Turner, 1996; Balam-Ballote et al., 2020), they also provide basic information on the conservation status of a region, as certain species are indicators of ecosystem health and quality (Rumiz, 2010; Isasi-Catalá, 2011). In addition, the inventories are the basis for studies on the interactions between groups of taxa, such as predator-prey relationships, migration, and adaptation to different environments (Farías et al., 2015). Despite their importance, the presence and distribution of most of the mammals in Mexico is still unknown (Ochoa-Espinoza et al., 2023).

Puebla is one of the states with the greatest natural wealth in Mexico, due to its location in the transition zone between the Nearctic and Neotropical regions, which generates climatic conditions and forest ecosystems suitable for the existence of mammals and other taxa (Conabio, 2011; Hernández et al., 2017). However, anthropogenic activities have affected the habitat conditions of the wildlife, putting at risk the biodiversity, which in many cases has not yet been inventoried (Conabio, 2011).

The tropical forests in the northern and northeastern range Sierra of Puebla consist of small discontinuous fragments of Evergreen tropical rain forest (ETRF), and it is estimated that 80 % of the native vegetation of this ecosystem has been replaced by grasslands and agriculture (Evangelista et al., 2010). This situation represents a special risk for the populations of large and medium-sized mammals, which due to their size and ecological habits require large interconnected areas of vegetation for their development and survival (Charre-Medellín et al., 2016). These conditions are scarce, therefore, alternatives must be sought to formulate viable strategies for their protection and conservation.

One of the largest and best-preserved areas of the Northeastern range Sierra of the state of Puebla is located in Las Margaritas Experimental Site (SELM, by its acronym in Spanish), which belongs to the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias and is located between the Hueytamalco and San José Acateno municipalities. The extent and degree of recovery of the Evergreen tropical rain forest allow it to play a fundamental role in the region's ecosystem services (Ordóñez-Prado et al., 2022). This also offers the opportunity to carry out studies on the diversity of the fauna in order to help design effective protection and conservation strategies. The objective of this research was to estimate the diversity of medium-sized and large mammal species by photo-trapping in high grass and the Evergreen tropical rain forest of the SELM.

Materials and Methods

Study area

The study was conducted in the tropical forests of the Las Margaritas Experimental Site, located in the northwest of the state of Puebla between Hueytamalco and San José Acateno municipalities (Figure 1); this site has 2 523 ha of surface area, 84 % of which is covered by Evergreen tropical rain forest and high grass.

ETRF = Evergreen tropical rain forest.

Figure 1 Location of the Las Margaritas Experimental Site, Hueytamalco and San José Acateno municipalities of Puebla, Mexico.

The floristic composition is represented by timber species such as Brosimum alicastrum Sw., Croton draco var. draco Schltld. et Cham., Matudaea trinervia Lundell, Cymbopetalum baillonii R. E. Fr., Guatteria amplifolia Triana & Planch., Alchornea latifolia Sw., Dussia mexicana (Standl.) Harms, and to a lesser extent, Cedrela odorata L., Swietenia macrophylla King, and Quercus spp. (Ordóñez-Prado et al., 2022). The climate is semi-warm humid within the temperate range, with an average annual rainfall of 3 153 mm, an average temperature of 21 °C, and extreme temperatures of 8 and 35 °C (García, 2004). The orography consists of a series of hills between 400 and 500 meters above sea level.

Field data collection

Medium-sized and large mammals were monitored in the Evergreen tropical rain forest (ETRF) and secondary forest is better, high grass is misleading. Those areas with vegetation composed of tree species over 20 m high, lianas, and arborescent ferns were considered as ETRF; those that had the presence of secondary vegetation characteristic of the ecological succession of abandoned pastures, with grass and thorny herbaceous species, were regarded as high grass. Based on the description by Hernández-Rodríguez et al. (2019), medium mammals are species with a body weight of 1 to 20 kg, and large mammals weigh >20 kg. The sampling period started in September 2016 and ended in May 2018. A simultaneous and independent photo-trapping monitoring design was established for the two vegetation types.

Prior to the sampling, SELM workers were interviewed to determine those areas where mammals were present, followed by reconnaissance surveys, in which tracks, droppings, trails, scratching grounds, and displacement areas were located. Based on this information, six digital camera traps (ScoutGuard® SG2060-U) with motion sensors were placed at strategic points: three in the high grass and three in the ETRF, georeferenced with a Garmin ℮Trex® 30x GPS navigator. The camera traps were placed on trees at 40-50 cm above the ground, with a south-north orientation (Gutiérrez-González et al., 2012; Cruz-Jácome et al., 2015), and were programmed to remain active 24 hours a day. The data were collected once a month, and the cameras were relocated every 30 days, maintaining a minimum separation distance of 500 m between them. At each sampling site, attractants such as scents were placed on logs, the baits were fats, sardines, tuna, cereals, and fruits. The coordinates of the camera trap locations are not included due to hunting issues in the study area.

A database was created with information on the species, sex, taxonomic arrangement, date, time, and geographic location for each record (Ceballos and Oliva, 2005; Aranda, 2012; Ramírez-Pulido et al., 2014). Independent photographic records were integrated into one file when all the photographs of a particular species corresponded to a 24 h period. Gregarious species were considered to be those of which two or more individuals were observed together in the photographs (Monroy-Vilchis et al., 2011), and the total sampling effort was calculated by adding up the number of days on which the camera traps were active. The conservation status of each taxon was verified in NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 updated in 2019 (Secretaría de Gobernación, 2019) and in the red list of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, 2023).

Statistical analysis

The species richness of the ETRF and of the high grass was estimated by counting the species registered for each unit of the sample collection effort and compared using a Student’s t-test for independent samples. A presence-absence matrix was generated to estimate the richness of mammals using the rarefaction method, with the Vegan package of the R software (Oksanen et al., 2014). With this information, species accumulation curves by vegetation type were generated.

The Relative abundance index (RAI) of each species observed was calculated using Equation 1 (Zamora, 2012; Lira-Torres et al., 2014).

Where:

Alpha diversity (α), defined as species diversity at the local level, was estimated using the Shannon-Wiener index (H’). It was complemented with Simpson's Dominance Index (λ) and the Pielou Equity Index (J´), calculated with the following equations (Moreno, 2001):

Where:

n = Number of specimens per species

N = Total number of organisms’ present

J´= Pielou Equity Index

S = Number of species

The beta diversity (β) was determined with the Jaccard Index, which estimates the similarity in habitats (Equation 5) (Magurran, 2005); this quantifies the number of totally different communities that are present in a region. In addition, it reports on the degree of differentiation between the biological communities of the sites in that region (Calderón-Patrón et al., 2012).

Where:

The diversity (α) of both vegetation types was compared with Hutchinson's t, the degree of dissimilarity was obtained based on the species’ complementarity between pairs of habitats, the rate of complementarity between habitats was estimated based on the number of shared species over the total number of species between habitats (Moreno, 2001; Magurran, 2005).

Results

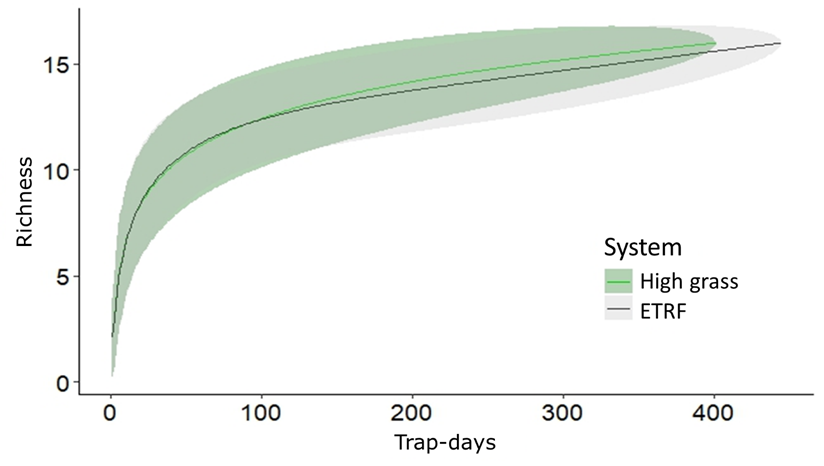

The sampling effort was 2 951 trap-days over 21 months. A total of 3 393 photographic records were obtained, of which 1 271 were identified as independent. At the vegetation type level, the sampling effort in the high grass was 1 459 trap-days, with 294 independent records, and in the Evergreen tropical rain forest it was 1 492 trap-days with 315 independent records. Figure 2 shows the species accumulation curve for the high grass and the ETRF as a function of sampling effort measured in trap-days. This exhibited an almost asymptotic trend in less than 100 days of sampling, which indicates that the likelihood of finding another species in both vegetation types after that time period is less than 5 %.

ETRF = Evergreen tropical rain forest.

Figure 2 Accumulation curves of medium-sized and large mammal species recorded by photo-trapping at the Las Margaritas Experimental Site, Puebla, Mexico.

19 species of medium-sized and large mammals were registered, belonging to six orders and 10 families. Table 1 shows the species composition, the independent records, and the conservation status in the norm NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 and in the IUCN red list. Four species of felines were recorded. Based on Mexican Official Norm 059, 20 % of the taxa recorded are under some kind of protection status. While the IUCN classifies Leopardus wiedii Schinz, 1821 as “Near threatened”, and the others as of “Least concern”, therefore, L. wiedii is considered as near threatened, and the other mammalian taxa, as of least concern.

Table 1 Composition of medium-sized and large mammals at the Las Margaritas Experimental Site, Hueytamalco municipality, Puebla.

| Order | Family | Species | Records | Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETRF | High grass | Total | NOM-059 | IUCN | |||

| Artiodactyla | Cervidae | Odocoileus virginianus veraecrucis Goldman and Kellogg, 1940 | 65 | 38 | 103 | LC | |

| Carnivora | Canidae | Canis latrans Say, 1822 | 24 | 18 | 42 | LC | |

| Urocyon cinereoargenteus Schreber, 1775 | 0 | 2 | 2 | LC | |||

| Felidae | Herpailurus yagouaroundi È. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1803 | 1 | 0 | 1 | T | LC | |

| Leopardus pardalis Linnaeus, 1758 | 15 | 18 | 33 | E | LC | ||

| Leopardus wiedii Schinz, 1821 | 0 | 2 | 2 | E | NT | ||

| Puma concolor Linnaeus, 1771 | 2 | 0 | 2 | LC | |||

| Mephitidae | Conepatus leuconotus Lichtenstein, 1832 | 1 | 1 | 2 | LC | ||

| Procyonidae | Nasua narica Linnaeus, 1766 | 209 | 112 | 321 | LC | ||

| Potos flavus Schreber, 1774 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Pr | LC | ||

| Procyon lotor Linnaeus, 1758 | 70 | 66 | 136 | LC | |||

| Cingulata | Dasypodidae | Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus, 1758 | 93 | 78 | 171 | LC | |

| Didelphimorphia | Didelphidea | Didelphis marsupialis Linnaeus, 1758 | 165 | 120 | 285 | LC | |

| Didelphis virginiana Kerr, 1792 | 56 | 49 | 105 | LC | |||

| Philander opossum Linnaeus, 1758 | 6 | 10 | 16 | LC | |||

| Pilosa | Myrmecophagidae | Tamandua mexicana de Saussure, 1860 | 1 | 4 | 5 | E | LC |

| Rodentia | Cuniculidae | Cuniculus paca Linnaeus, 1766 | 8 | 8 | 16 | LC | |

| Sciuridae | Sciurus aureogaster F. Cuvier, 1829 | 18 | 3 | 21 | LC | ||

| Sciurus deppei Peters, 1864 | 7 | 0 | 7 | LC | |||

| Total | 741 | 530 | 1271 | ||||

ETRF = Evergreen tropical rain forest; T = Threatened; E = Endangered; Pr = Special protection; NOM-059 = NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010; IUCN = International Union for Conservation of Nature; LC = Least concern; NT = Near threatened.

According to the IUCN, the populations of Cuniculus paca Linnaeus, 1766, Leopardus pardalis Linnaeus, 1758, Puma concolor Linnaeus, 1771, Leopardus wiedii, Herpailurus yagouaroundi È. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1803, Potos flavus Schreber, 1774, Nasua narica Linnaeus, 1766, and Conepatus leuconotus Lichtenstein, 1832 are diminishing, while the populations of the other species identified are stable or increasing. Figure 3 shows the photographic evidence of medium-sized and large mammals recorded in the SELM.

A = Odocoileus virginianus veraecrucis Goldman and Kellogg, 1940; B = Canis latrans Say, 1822; C = Urocyon cinereoargenteus Schreber, 1775; D = Herpailurus yagouaroundi È. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1803; E = Leopardus pardalis Linnaeus, 1758; F = Leopardus wiedii Schinz, 1821; G = Puma concolor Linnaeus, 1771; H = Conepatus leuconotus Lichtenstein, 1832; I = Nasua narica Linnaeus, 1766; J = Potos flavus Schreber, 1774; K = Procyon lotor Linnaeus, 1758; L = Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus, 1758; M = Didelphis marsupialis Linnaeus, 1758; N = Didelphis virginiana Kerr, 1792; O = Philander opossum Linnaeus, 1758; P = Tamandua mexicana de Saussure, 1860; Q = Cuniculus paca Linnaeus, 1766; R = Sciurus aureogaster F. Cuvier, 1829; S = Sciurus deppei Peters, 1864.

Figure 3 Mammals recorded by photo-trapping at the Las Margaritas Experimental Site, northeastern Sierra of the state of Puebla. The collection of photographs is under the custody of INIFAP, and can be consulted upon request to Dra. Martha Elena Fuentes López.

Taxa presented different relative abundances in the two vegetation conditions studied (Figure 4a). Nasua narica, Didelphis marsupialis Linnaeus, 1758, and Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus, 1758 were the most abundant for both conditions, while Herpailurus yagouaroundi and Puma concolor the lowest values and were only recorded in the ETRF; L. wiedii Schinz was observed only in the high grass.

a) Relative Abundance Index (RAI); b) Alpha diversity (H’). ETRF = Evergreen tropical rain forest.

Figure 4 Relative abundance and proportional abundance of medium-sized and large mammals.

Based on the Shannon-Wiener Index, it was determined that the habitat with the highest alpha diversity (α) was the ETRF, with an H' of 2.11, while that of the high grass was 2.04; however, these differences were not statistically significant (p=0.92). Figure 4b shows the estimated H' by species, whose values were very similar in the two vegetation types. Simpson’s Dominance Index (λ) in the ETRF was 0.14 and 0.16 for the high grass, indicating for the analyzed habitats that there is high diversity and low preponderance of any particular species. The above is confirmed by the Pielou Equity Index (J'), whose values of 0.94 and 0.89 for the ETRF and the high grass, respectively, show that most of the species recorded are equally abundant in both vegetation types.

The beta diversity value (β) was 68 %, with 13 species shared in the two vegetation types, representing an intermediate similarity between the two. In terms of complementarity, the dissimilarity rate between the ETRF and the high grass was 32 %, with six species not shared, Herpailurus yagouaroundi, Potos flavus and Urocyon cinereoargenteus Schreber, 1775 were predominant. The three most abundant taxa in both vegetation types were Didelphis marsupialis, Nasua narica and Dasypus novemcinctus.

Discussion

As for the monitoring period, in their study on the diversity of medium-sized mammals in Pico de Orizaba National Park, Serna-Lagunes et al. (2019) conducted a sampling effort of 4 928 trap-days and obtained 191 independent records with values below those cited in the present paper. The research presented herein provides outstanding information on the richness of medium-sized and large mammals that complements the works of Villareal et al. (2005), Ramírez-Bravo et al. (2010), and Silverio and Ramírez-Bravo (2014). The latter documents a richness of 13 species of medium-sized and large mammals for the region; however, a greater species richness was documented in the SELM.

The H' and J' values in the two vegetation types and the species accumulation curve suggest that the inventory of medium-sized and large mammals is complete and very representative of the total number of species that this tropical forest fragment can support. Given that the J’ (equity) values were high, the diversity of mammal species (H’) was very close to the maximum expected in the two vegetation types.

The degree of similarity between the ETRF and the high grass suggests little differentiation in terms of the existing habitats for medium-sized and large mammals. It also indicates that the mobility of most species is facilitated by the ecological conditions prevailing in the SELM.

The richness of mammal species (19) of the SELM is higher than the nine species recorded by Gallina and González-Romero (2018) in a private reserve in Vega de la Torre and than the 14 species identified in a reserve in Los Tuxtlas, both located in the state of Veracruz. It is also higher than that cited by Chávez-León (2019) for temperate forests under management in the Northern Sierra of Puebla, where he recorded 13 mammal species by photo-trapping, and than that reported by Serna-Lagunes et al. (2019) in the Pico de Orizaba National Park, consisting of 10 mammal species. The differences mentioned above may be due to the type of ecosystem under study, the studied area, the level of conservation, and the sampling effort, among other factors; however, the results of the present study indicate that they are sufficiently representative in terms of sampling coverage and observed mammal richness values.

The SELM results are consistent with those indicated for locations farther away from the study area; for example, several studies carried out in southern Mexico (Hernández et al., 2018; Hernández-Rodríguez et al., 2019; Pozo-Montuy et al., 2019; Ruiz-Gutiérrez et al., 2020).

Most prominent among the taxa recorded is Didelphis marsupialis (common opossum), a species considered a generalist, since its habitat transcends any type of natural vegetation and disturbed areas, it is one of the most abundant taxa in wildlife studies (Orjuela and Jiménez, 2004). Nasua narica (coati or badger), also exhibited a high number of records; this is a gregarious species, which reproduces rapidly and whose feeding habits facilitate its adaptation to fragmented or altered ecosystems (Espinoza-García et al., 2014). There are numerous records of species of wide distribution and great mobility, such as Leopardus pardalis, Puma concolor and Canis latrans Say, 1822, whose home environments can exceed a surface area of 100 km2 (Servín et al., 2014). The above highlights the importance of the SELM in terms of habitat availability for this group of species despite its relatively small surface area, which is about a quarter of that required by these mammals, the presence of these species suggests that the SELM provides suitable conditions to serve as a refuge for them in the region.

The alpha diversity (α) recorded shows a moderately high intrinsic biodiversity for the two vegetation types. The alpha diversity values estimated for both types are similar to those documented by Del Rio-García et al. (2014), who determined a value of H'=2.05 in a tropical forest of Santiago Comaltepec, Oaxaca, Mexico; they also coincide with those of Lavariega et al. (2012), who recorded an H' of 2.39 for medium-sized and large mammals in the Sierra de Villa Alta, Oaxaca.Monroy-Vilchis et al. (2011) cite an H' of 2.3 for medium-sized and large mammals in the Sierra de Nanchititla Nature Reserve, Oaxaca, while Arroyo et al. (2013) estimate an H' of 2.52 in the Sumidero Canyon National Park, state of Chiapas.

The estimated beta diversity (β) of the high grass and the ETRF of the SELM indicates that the rate of species turnover between the two is low, given that they share the majority of taxa. Consequently, it is concluded that they present similar ecological characteristics of habitat and landscapes for the mastofauna. This is clearly seen with the Felidae family, composed of the Leopardus pardalis, L. wiedii, Puma concolor and H. yagouaroundi, all of which are highly mobile species. In addition, their small number suggests that the studied vegetation types exhibit suitable ecological characteristics for the presence or permanence of the recorded specimens. The alpha diversity (α) results are also consistent with similar studies in other geographic regions of Mexico (Hernández et al., 2018; Hernández-Rodríguez et al., 2019; Ruiz-Gutiérrez et al., 2020).

Conclusions

In the SELM there are 19 species of medium-sized and large mammals belonging to six orders and 10 families. The estimated alpha diversity in the two vegetation types comprised in the site indicates moderate values of mammal diversity, similar to that reported in other localities of the study region. The considerable similarity or beta diversity of the two areas suggests adequate mobility of mammalian species, which is most notable in felids that prefer low-disturbance forest habitats.

The presence of indicator or umbrella species (large felines) in the Evergreen tropical rain forest of the SELM, as well as of taxa with the NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 status, prove the importance of conserving and improving the ecosystems which are home to them as part of regional strategies for the conservation and protection of wild mammals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Volkswagen de México S. A. de C. V. for funding the project “Establishment of a sustainable native bamboo plantation (Guadua aculeata) in an area of 355 hectares in the Las Margaritas Experimental Site, Hueytamalco municipality, Puebla”.

REFERENCES

Aranda S., J. M. 2012. Manual para el rastreo de mamíferos terrestres de México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (Conabio). Tlalpan, México D. F., México. 255 p. [ Links ]

Arroyo C., E., A. Riechers P., E. J. Naranjo y G. Rivera-Velázquez. 2013. Riqueza, abundancia y diversidad de mamíferos silvestres entre hábitats en el Parque Nacional Cañón del Sumidero, Chiapas, México. THERYA 4(3):647-676. Doi: 10.12933/therya-13-140. [ Links ]

Balam-Ballote, Y. del R., J. A. Cimé-Pool, S. F. Hernández-Betancourt, J. M. Pech-Canché, J. C. Sarmiento-Pérez y S. Canul-Yah. 2020. Mastofauna del ejido X-Can, Chemax, Yucatán, México. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología, Nueva Época 10(2):1-16. Doi: 10.22201/ie.20074484e.2020.10.2.313. [ Links ]

Calderón-Patrón, J. M., C. E. Moreno e I. Zuria. 2012. La diversidad beta: medio siglo de avances. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 83(3):879-891. Doi: 10.7550/rmb.25510. [ Links ]

Ceballos G., G. y G. Oliva (Coords.). 2005. Los mamíferos silvestres de México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (Conabio) y Fondo de Cultura Económica. Tlalpan, México D. F., México. 986 p. [ Links ]

Charre-Medellín, J. F., G. Magaña-Cota, T. C. Monterrubio-Rico, R. Tafolla-Muñoz, J. L. Charre-Luna y F. Botello. 2016. Mamíferos medianos y grandes del municipio de Victoria, Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra Gorda Guanajuato, México. Acta Universitaria 26(2):62-70. Doi: 10.15174/au.2016.1438. [ Links ]

Chávez-León, G. 2019. Diversidad de mamíferos y aves en bosques de coníferas bajo manejo en el Eje Neovolcánico Transversal. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 10(56):85-112. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v10i56.499. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (Conabio). 2011. La Biodiversidad en Puebla: Estudio de Estado. Conabio, Gobierno del Estado de Puebla y Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. Tlalpan, México D. F., México. 440 p. https://smadsot.puebla.gob.mx/images/Biodiversidad_en_Puebla2.pdf . (15 de junio de 2021). [ Links ]

Cruz-Jácome, O., E. López-Tello, C. A. Delfín-Alfonso y S. Mandujano. 2015. Riqueza y abundancia relativa de mamíferos medianos y grandes en una localidad en la Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, Oaxaca, México. THERYA 6(2):435-448. Doi: 10.12933/therya-15-277. [ Links ]

Del Rio-García, I. N., M. K. Espinoza-Ramírez, M. D. Luna-Krauletz y N. U. López-Hernández. 2014. Diversidad, distribución y abundancia de mamíferos en Santiago Comaltepec, Oaxaca, México. Agro Productividad 7(5):17-23. https://revista-agroproductividad.org/index.php/agroproductividad/article/view/550 . (23 de noviembre 2021). [ Links ]

Espinoza-García, C. R., J. M. Martínez-Calderas, J. Palacio-Núñez y A. D. Hernández-SaintMartín. 2014. Distribución potencial del coatí (Nasua narica) en el noreste de México: implicaciones para su conservación. THERYA 5(1):331-345. Doi: 10.12933/therya-14-195. [ Links ]

Evangelista O., V., J. López B., J. Caballero N. y M. Á. Martínez A. 2010. Patrones espaciales de cambio de cobertura y uso del suelo en el área cafetalera de la sierra norte de Puebla. Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía, UNAM (72):23-38. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/igeo/n72/n72a3.pdf . (16 de julio de 2022). [ Links ]

Farías, V., O. Téllez, F. Botello, O. Hernández, … y J. C. Hernández. 2015. Primeros registros de 4 especies de felinos en el sur de Puebla, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 86(4):1065-1071. Doi: 10.1016/j.rmb.2015.06.014. [ Links ]

Gallina, S. y A. González-Romero. 2018. La conservación de mamíferos medianos en dos reservas ecológicas privadas de Veracruz, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 89(4):1245-1254. Doi: 10.22201/ib.20078706e.2018.4.2476. [ Links ]

García, E. 2004. Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de köppen. Instituto de Geografía de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Coyoacán, México D. F., México. 90 p. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez-González, C. E., M. Á. Gómez-Ramírez and C. A. López-González. 2012. Estimation of the density of the near threatened jaguar Panthera onca in Sonora, Mexico, using camara trapping and an open population model. Oryx 46(3):431-437. Doi: 10.1017/S003060531100041X. [ Links ]

Hernández H., J. C., C. Chávez y R. List. 2018. Diversidad y patrones de actividad de mamíferos medianos y grandes en la Reserva de la Biosfera La Encrucijada, Chiapas, México. Revista de Biología Tropical 66(2):634-646. Doi: 10.15517/rbt.v66i2.33395. [ Links ]

Hernández R., E., O. E. Ramírez-Bravo y G. Hernández T. 2017. Patrones de cacería de mamíferos en la Sierra Norte de Puebla. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 33(3):421-430. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/azm/v33n3/2448-8445-azm-33-03-421.pdf . (30 de marzo 2022). [ Links ]

Hernández-Rodríguez, E., L. Escalera-Vázquez, J. M. Calderón-Patrón y E. Mendoza. 2019. Mamíferos medianos y grandes en sitios de tala de impacto reducido y de conservación en la sierra Juárez, Oaxaca. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 90:1-10. Doi: 10.22201/ib.20078706e.2019.90.2776. [ Links ]

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). 2023. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2022-2. https://www.iucnredlist.org . (9 de junio del 2023). [ Links ]

Isasi-Catalá, E. 2011. Los conceptos de especies indicadoras, paraguas, banderas y claves: su uso y abuso en ecología de la conservación. Interciencia 36(1):31-38. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/339/33917727005.pdf . (05 de noviembre de 2022). [ Links ]

Lavariega, M. C., M. Briones-Salas y R. M. Gómez-Ugalde. 2012. Mamíferos medianos y grandes de la Sierra de Villa Alta, Oaxaca, México. Mastozoología Neotropical 19(2):225-241. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45725085002 . (12 de abril de 2022). [ Links ]

Leija, E. G., N. P. Pavón, A. Sánchez-González, R. Rodríguez-Laguna y G. Ángeles-Pérez. 2021. Dinámica espacio-temporal de uso, cambio de uso y cobertura de suelo en la región centro de la Sierra Madre Oriental: implicaciones para una estrategia REDD+ (Reducción de Emisiones por la Deforestación y Degradación). Revista Cartográfica 102:43-68. Doi: 10.35424/rcarto.i102.832. [ Links ]

Lira-Torres, I., M. Briones-Salas y G. Sánchez-Rojas. 2014. Abundancia relativa, Estructura poblacional, preferencia de hábitat y patrones de actividad del tapir centroamericano Tapirus bairdii (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae), en la selva de Los Chimalapas, Oaxaca, México. Revista de Biología Tropical 62(4):1407-1419. https://www.scielo.sa.cr/pdf/rbt/v62n4/a12v62n4.pdf . (12 de abril de 2022). [ Links ]

Magurran, A. E. 2005. Species abundance distributions: Pattern or Process? Functional Ecology 19(1):177-181. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3599287 . (24 de diciembre de 2022). [ Links ]

Mezhua-Velázquez, M. J., R. Serna-Lagunes, G. B. Torres-Cantú, L. D. Pérez-Gracida, J. Salazar-Ortiz y N. Mora-Collado. 2022. Diversidad de mamíferos medianos y grandes del Ejido Zomajapa, Zongolica, Veracruz, México: implicaciones de manejo. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios 9(2):1-15. Doi: 10.19136/era.a9n2.3316. [ Links ]

Monroy-Vilchis, O., M. M. Zarco-González, C. Rodríguez-Soto, L. Soria-Díaz y V. Urios. 2011. Fototrampeo de mamíferos en la Sierra Nanchititla, México: abundancia relativa y patrón de actividad. Revista de Biología Tropical 59(1):373-383. https://www.scielo.sa.cr/pdf/rbt/v59n1/a33v59n1.pdf . (20 de mayo de 2021). [ Links ]

Moreno, C. E. 2001. Métodos para medir la biodiversidad. Programa Iberoamericano de Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo (Cyted), Oficina Regional de Ciencia y Tecnología para América Latina y el Caribe (Unesco) y Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa (SEA). Zaragoza, Z, España. 83 p. [ Links ]

Ochoa-Espinoza, J. M., L. Soria-Díaz, C. C. Astudillo-Sánchez, J. Treviño-Carreón, C. Barriga-Vallejo y E. Maldonado-Camacho. 2023. Diversidad y abundancia de mamíferos del bosque mesófilo de montaña del noreste de México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie) 39:1-18. Doi: 10.21829/azm.2023.3912591. [ Links ]

Oksanen, J., F. G. Blanchet, R. Kindt, P. Legendre, … and H. Wagner. 2014. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.2-0. http://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=vegan . (02 de febrero de 2023). [ Links ]

Ordóñez-Prado, C., J. C. Tamarit-Urias, E. Buendía-Rodríguez y G. Orozco-Gutiérrez. 2022. Estimación e inventario de biomasa y carbono del bambú nativo Guadua aculeata Rupr. en Puebla, México. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 25(47):1-14. Doi: 10.56369/tsaes.3787. [ Links ]

Orjuela C., O. J. y G. Jiménez. 2004. Estudio de la abundancia relativa para mamíferos en diferentes tipos de coberturas y carretera, Finca Hacienda Cristales, Área Cerritos-La Virginia, municipio de Pereira, Departamento de Risaralda-Colombia. Universitas Scientiarum 9(1):87-96. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=49909408 . (23 de junio de 2021). [ Links ]

Pérez-Solano, L. A., M. González, E. López-Tello y S. Mandujano. 2018. Mamíferos medianos y grandes asociados al bosque tropical seco del centro de México. Revista de Biología Tropical 66(3):1232-1243. https://www.scielo.sa.cr/pdf/rbt/v66n3/0034-7744-rbt-66-03-1232.pdf . (29 de septiembre de 2022). [ Links ]

Pozo-Montuy, G., A. A. Camargo-Sanabria, I. Cruz-Canuto, K. Leal-Aguilar y E. Mendoza. 2019. Análisis espacial y temporal de la estructura de la comunidad de mamíferos medianos y grandes de la Reserva de la Biosfera Selva El Ocote, en el sureste mexicano. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 90:e902731. Doi: 10.22201/ib.20078706e.2019.90.2731. [ Links ]

Ramírez-Bravo, O. E., E. Bravo-Carrete, C. Hernández-Santín, S. Schinkel-Brault and K. Chris. 2010. Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) distribution in the state of Puebla, Central Mexico. THERYA 1(2):110-120. Doi: 10.12933/therya-10-12. [ Links ]

Ramírez-Pulido, J., N. González-Ruiz, A. L. Gardner and J. Arroyo-Cabrales. 2014. List of recent land mammals from Mexico. Museum of Texas Tech University. Lubbock, TX, United States of America. 69 p. [ Links ]

Ruiz-Gutiérrez, F., C. Chávez, G. Sánchez-Rojas, C. E. Moreno, … y R. Torres-Bernal. 2020. Mamíferos medianos y grandes de la Sierra Madre del Sur de Guerrero, México: evaluación integral de la diversidad y su relación con las características ambientales. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 91:1-15. Doi: 10.22201/ib.20078706e.2020.91.3168. [ Links ]

Rumiz, D. I. 2010. Roles ecológicos de los mamíferos medianos y grandes. In: Wallace, R. B., H. Gómez, Z. R. Porcel y D. I. Rumiz (Edits). Distribución, ecología y conservación de los mamíferos medianos y grandes de Bolivia. Centro de Ecología Difusión Fundación Simón I. Patino. Santa Cruz de la Sierra, S, Bolivia. pp. 53-73. [ Links ]

Salazar-Ortiz, J., M. Barrera-Perales, G. Ramírez-Ramírez y R. Serna-Lagunes. 2020. Diversidad de mamíferos del municipio de Tequila, Veracruz, México. Abanico Veterinario 10:1-18. Doi: 10.21929/abavet2020.30. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Gobernación . 2019. MODIFICACIÓN del Anexo Normativo III, Lista de especies en riesgo de la Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección ambiental-Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres-Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio-Lista de especies en riesgo, publicada el 30 de diciembre de 2010. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 14 de noviembre de 2019. México, D. F., México. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5578808&fecha=14/11/2019#gsc.tab=0 . (1 de junio de 2023). [ Links ]

Serna-Lagunes, R., N. Hernández-García, L. R. Álvarez-Oseguera, C. Llarena-Hernández, … y R. Núñez-Pastrana. 2019. Diversidad de mamíferos medianos en el Parque Nacional Pico de Orizaba. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios 6(18):423-434. Doi: 10.19136/era.a6n18.2054. [ Links ]

Servín, J., A. Bejarano, N. Alonso-Pérez y E. Chacón. 2014. El tamaño del ámbito hogareño y el uso de hábitat de la zorra gris (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) en un bosque templado de Durango, México. THERYA 5(1):257-269. Doi: 10.12933/therya-14-174. [ Links ]

Silverio P., L. y O. E. Ramírez-Bravo. 2014. Registro de la presencia de mamíferos medianos en dos zona del municipio de Cuetzalán, en la Sierra Norte de Puebla. THERYA 5(3):855-860. Doi: 10.12933/therya-14-163. [ Links ]

Turner, I. M. 1996. Species loss in fragments of tropical rain forest: a review of the evidence. Journal of Applied Ecology 33(2):200-209. Doi: 10.2307/2404743. [ Links ]

Villareal E., O. A., R. Guevara V., R. Reséndiz M., J. S. Hernández Z., J. C. Castillo C. y F. J. Tomé T. 2005. Diversificación productiva en el Campo Experimental Las Margaritas, Puebla, México. Archivos de Zootecnia 54(206-207):197-203. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=49520713 . (1 de marzo de 2021). [ Links ]

Zamora G., J. 2012. Manual Básico de Fototrampeo. Aplicado al estudio de vertebrados terrestres. Tundra ediciones. Almenara, CS, España. 92 p. [ Links ]

Received: April 12, 2023; Accepted: June 29, 2023

texto en

texto en