Introduction

The margay (Leopardus wiedii, Schinz 1821) is widely distributed in South and Central America to its northernmost distribution extending into Northeastern Mexico (Hall 1981; Aranda 2005). Basic information on the abundance and distribution of margays in this area and the rest of country is poorly understood. Several studies mention that the margay is closely linked to forest habitats, especially in tropical and subtropical areas because it is generally considered to be more arboreal and better adapted to live in trees than other cat species (Bisbal 1989; Oliveira 1998). This makes it more vulnerable to deforestation (Tewes and Schmidly 1987) and, in Mexico, this felid is listed as endangered on the NOM-059 SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT 2010), although internationally it is considered as threatened (Payan et al. 2008). The habitat of this species is being destroyed or converted to agriculture and other land uses along its entire distribution and new studies suggest that its abundance is lower than previously thought. Therefore, it is crucial to generate potential species distribution models to be used as a baseline for the future conservation efforts of the margay (Ferrier and Guisan 2006; Payan et al. 2008; Oliveira et al. 2010).

Today, the use of algorithms in the development of predictive and potential species distribution models has increased. Potential distribution is calculated from georeferenced observations and variables that act as predictors. Thanks to its predictive capacity and robustness in generating species distribution models, one of the most widely used algorithms is MaxEnt (Elith et al. 2006; Phillips et al. 2006). This algorithm generates distribution probabilities for the concerned species in a particular region, based on different variables that can be environmental (climate, vegetation type, topography), demographic or anthropogenic. It is constructed exclusively on current conditions present in the localities where the species occurs (Elith et al. 2006; Pearson et al. 2007). The software determines the distribution through the adjustment of the species occurrence probability in pixels throughout the study area. This is based on the idea that the best possible explanation for an unknown phenomenon maximizes the entropy or uncertainty of the distribution of the probability, depending on certain limitations. Concerning potential distribution models, they consist of values of those pixels in which the species has been detected (Phillips et al. 2004; Phillips et al. 2006). This study is part of a regional project on the ecology and conservation of wild felids in Mexico, and its purpose was to estimate the potential distribution of margays (Leopardus wiedii) in Northeastern Mexico.

Methods

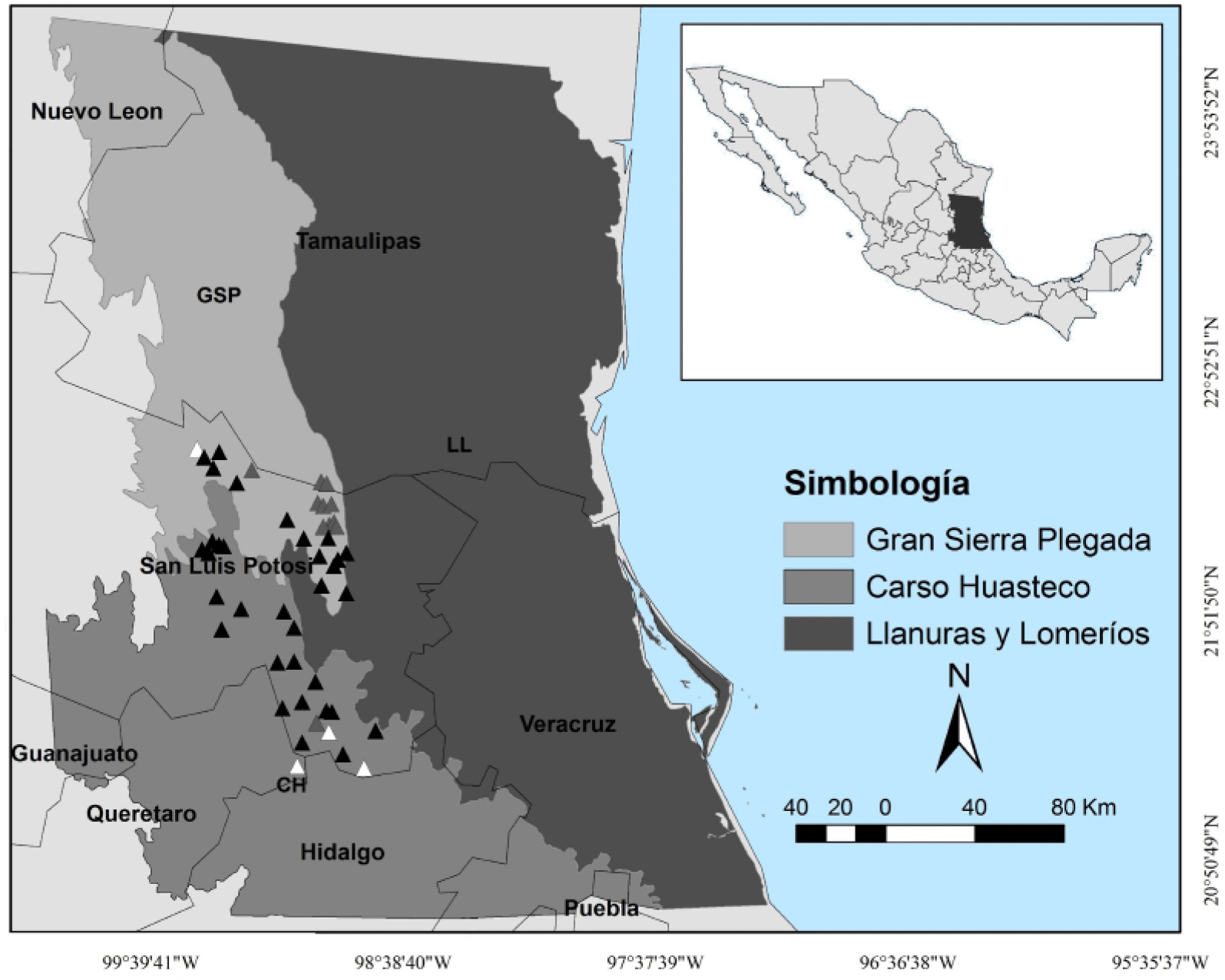

Study area. The study area partially covers two physiographic provinces (84,523 km2): Sierra Madre Oriental and Llanura Costera del Golfo Norte. In the first, it included part of the physiographic subprovinces Gran Sierra Plegada (GSP) and Carso Huasteco (CH). In the second, only the subprovince Llanuras y Lomerios (LL) was partially included (Figure 1). The characteristics of these subprovinces have great relevance in the landscape structure and degree of conservation. While in LL there is great antrophogenic impact throughout its surface due to topographic conditions, in CH, and mostly in GSP, large remnants of habitat remain in good condition. In this region, topography is flat to undulating towards the East and rough towards the West, with a wide range of climatic conditions from tropical to temperate, that varies from humid to semidry. There is a clear seasonal variation regarding precipitation, as well as a clear difference between the amount of rainfall in one region and the other. Altitude ranges from 0 to 2,300 m and precipitation from 600 to 2,500 mm.

Figure 1 Study area with the location of physiographic subprovinces and margay records in Northeastern Mexico, which including portions of the states of Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, San Luis Potosí, Veracruz, Guanajuato, Querétaro, Hidalgo, and Puebla. The white triangles are historical records, blacks are the literature records (Martínez-Calderas et al. 2012), and grays are of fieldwork and surveys records.

Anthropic land use is widespread within the study area for farming, agriculture and, in some regions, wood extraction (INEGI 2002a). The types of land use and vegetation are shown on Table 1. In this study there are 6 groups of native vegetation (NV) subdivided into 18 categories according to humidity and latitude gradients (Table 1). In GSP, the landscape corresponds to a mountainous karstic rock mass with irregular intermontane valleys, where anthropic use predominates (46.18 %). The native vegetation in GSP is dominated by tropical dry (26.99 %), followed by temperate (20.98 %) vegetation. Drier (2.86 %) and more humid tropical (1.02 %) types of vegetation are scarce. The landscape in CH is characterized by abrupt karstic mountains and intermontane valleys; anthropic use is 41.14 %, dominated by dry tropical (20.49 %) and dry (16.25 %) vegetation, followed by temperate vegetation (15.98 %). In LL, the terrain ranges from flat to undulated, where anthropic use is 50.86 % and dry tropical vegetation predominates (25.28 %), followed by temperate vegetation (18.08 %). Tropical humid (3.16 %) and dry (0.47 %) vegetation are scarce; other types of vegetation such as cattail marshes, palm forests, and riparian vegetation occupy 2.15 % of the landscape.

Table 1 Percentage by subprovince of Type of anthropic land use and native vegetation (NV) in Gran Sierra Plegada (GSP); Carso Huasteco (CH) and Llanuras y Lomerios (LL) of Northeastern Mexico.

Data collection and modeling. The information used for the development of the model was obtained from several sources. Thirty-six records come from a previous study (Martínez-Calderas et al. 2012), 13 were obtained through fieldwork with random camera-trapping sessions between August 2010 and March 2012, and four are georeferenced historical records (prior to the year 2000), obtained from the GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility) database provider (GBIF 2014).

For modeling, 27 predictive variables were used: 19 bioclimatic (Hijmans et al. 2005), two of vegetation (Hansen et al. 2000; INEGI 2002b), four derived from the digital elevation model (INEGI 2008), and two anthropic (CIAT et al. 2005; INEGI 2005). In order to generate the potential distribution model, we used the algorithm software MaxEnt (version 3.3.3k), which is based on a maximum entropy algorithm (Phillips et al. 2006). We used the method reported by Martínez-Calderas et al. (2015) for the realization of the model. The same methods were also successfully implemented in that study for ocelots. Default settings were: maximum number of background points = 10.000, regularization multiplier = 1, replicates = 20, replicate run type = bootstrap, convergence threshold = 0.00001, and maximum number of iterations = 10 000. From the occurrence data, 70 % was selected randomly as training data and 30 % as the test data set. We used the logistic output of MaxEnt with prediction values ranging from 0 (unsuitable habitat) to 1 (optimal habitat). To validate the performance of the model, the weight of the omission error and the commission error equally, we considered the area under curve (AUC), which is generated by the algorithm (Hernandez et al. 2006) and is obtained directly from the evaluation of the models through ROC curves (Receiver Operating Characteristic; e. g. Contreras-Medina et al. 2010). Moreover, variables in the model are assessed through a jackknife test that compares the models with all possible combinations of environmental variables by measuring the importance of the variable. This expressed the relative importance of every predictor variable separately in order to determine the percentage that each one provides to the model. The results obtained from the model in ASCII format were processed and reclassified using ArcGIS 9.2 (ESRI 2006). The binary map (absence-presence) for the potential distribution of the margay was generated (Figure 2) considering the average map that represents the induced and adjusted habitat of the species (Anderson et al. 2003; Burneo et al. 2009). We used the minimum presence training as threshold reclassification (0.2745). Finally, using this map and levels, we calculated the potential distribution area shown in percentage of the total area of each physiographic subprovince.

Results

The margay was recorded in diverse environmental conditions within the study area, in locations varying from very humid to semidry environments (Appendix 1). Regarding temperature, this species inhabit from very hot to temperate, and in an altitude ranging from 6 to 1,800 m (INEGI 2002b; INEGI 2008; INEGI 2011). Seven predictive variables explained 94.4 % of the model, showing an AUC of 0.964 ± 0.0097, where an AUC value higher than 0.9 indicates an excellent model (Araujo and Guisan 2006). The four most relevant variables were: precipitation of the most humid quarter, vegetation type, and both altitude and topographic indexes. Each of the other three remaining variables did not account for more than 3 % of the total contribution (Table 2).

Table 2 Predictive variables for the generation of the distribution model of L. wiedii in Northeastern Mexico.

The potential distribution area of the margay in Northeastern Mexico covered approximately 9 % of the total studied landscape, with an area of 7,607 km2. GSP and CH subprovinces showed the highest distribution, with a potential presence of 18.1 and 20.2 % on each surface, respectively. Conversely, LL accounted for only 0.4 % (Table 3). The highest potential distribution continuity was observed in the contiguous mountainous areas between GSP and CH. In all of LL, we only found small and isolated patches due to fragmentation (Figure 2).

Discussion

The use of historical records is a valuable tool for the modeling of elusive species (e. g. Wilting et al. 2010; Jenks et al. 2012). Besides the four historical records used in this research, there is no further information available to support the historical distribution of the margay in Northeastern Mexico. There have been some efforts to determine the distribution area using only these records, which has prompted the creation of maps that lack validity, such as those proposed by Hall 1981 and Aranda (2005).

In this study, we obtained a robust model based on the value of AUC according to Araujo and Guisan (2006). The most relevant variables that explain the potential distribution of the margay coincided with climatic fluctuation (Guggisberg 1975; Bisbal 1989; Azevedo 1996; Oliveira 1998). Moreover, these same authors mention that this species inhabits tropical regions, where the presence of tropical rain forest is frequent. Yet this species has also been reported to be present in induced grassland ecotones (Mondolfi 1986; Oliveira 1994; Martínez-Calderas et al. 2012), as long as there is closed-canopy arboreal vegetation nearby (Vaughan 1983; Mondolfi 1986; Tello 1986). Areas with the wettest climate conditions provide a better vegetation coverage, which was appropriate for the species in accordance with Bisbal (1989), Oliveira (1994), and Mondolfi (1986). This occurred in only 9.0 % of the study area. Regarding altitude, this species is known to live at heights ranging from sea level to 1,100 m (Oliveira 1994), or even 3,000 m in the valleys of the Andes (Tello 1986), meaning that these results fall within this range.

No reports have been produced to date that describe the relation between the presence of the margay and the topographic index or the slope range. However, the largest areas were located in mountainous localities of Sierra Madre Oriental, in the Southern portion of GSP, and in the Northern region of CH. An important portion of these subprovinces maintains continuity in the area of the potential distribution of the margay. They also contain large and nearby patches, which may guarantee connectivity among populations. However most of the study area showed only small isolated spots or areas with no potential distribution for the margay, especially in the portions of the flattest and driest terrains, mainly in LL.

Deforestation due to land-use change, mostly because of sugarcane cultivation or extensive ranching (Villordo-Galván et al. 2010), occupies a large portion of the study area. Crops (Jiménez et al. 2004) and induced grassland for cattle (Vieyra-Alberto et al. 2013) are established for the most part in flat or moderate slope terrains with deep soils. In this very fragmented landscape, remnants of closed vegetation exist only in terrains with steeper and often rough slopes, where neither agriculture nor livestock can occur (Guevara and Laborde 1999; Trejo and Dirzo 2000; Reyes-Hernández et al. 2007).

Habitat fragmentation alters the composition and structure of animal communities through the modification of ecological processes (v. gr. Wilcove 1985). In fragmented habitats, some populations tend to become isolated. The survival of the species depends on their ability to move between these patches, gaining access to the necessary resources, maintaining their genetic diversity, and keeping their reproductive capacity as a population (Petit et al. 1995; Buza et al. 2000). The species' sensitivity to change depends on its behavior and morphology (Wolff 1999; Laurance 1995; Buza et al. 2000; Nupp and Swihart 2000; Gehring and Swihart 2004), as well as on the availability of landscape elements (Gehring 2000). It is known that density of predators and, consequently, potential prey vulnerability is higher in small patches (Wilcove 1985; Andren 1992). Size can influence the area of activity and the possibility of moving within it (Gehring and Swihart 2004). Previous studies suggest that animals, even those extremely mobile, avoid passing through altered areas of habitat (Smallwood 1994; Machtans et al. 1996). For this reason, if there are gaps in the connection between two or more small populations, local extinctions can occur (v. gr. Beier 1993).

Among predators, the larger they are the bigger areas they require, which is why they are more susceptible to become locally extinct due to habitat loss. Moreover, in fragmented habitats conflicts with humans are more frequent (e. g. Crooks and Soulé 1999). Medium and small-sized carnivore populations such as the margay are often benefited by the decline of top predators and increase their numbers (Prugh et al. 2009; Oliveira et al. 2010). This produces a decrease in the population size of prey. Since the area of activity of a predator is in accordance with prey availability, fragmentation tends to create a general imbalance (Oehler and Litvaitis 1996). The area of activity of a predator is in accordance with prey availability. Thus, species of this kind are susceptible to fragmentation, and above all, to the size of the patch, which must maintain the adequate habitat conditions in order to improve the continuity of the species (e. g. Gehring and Swihart 2004). Studies mention that the Margay populations are negatively impacted by ocelot (through 'the ocelot effect' (Oliveira et al. 2010). However, both species are usually sympatric, and can share habitat and distributional range. Compared to the potential distribution ocelot (Martínez-Calderas et al. 2015), the margay was less extensive in this subprovinces. For example, in LL is wider the presence of the ocelot, mainly to the northeast of this region. Margay is present only in small isolated patches.

The disappearance of natural ecosystems is inherent to the encroachment in anthropogenic activities, especially in agricultural production. Sahagún-Sánchez et al. (2011) estimated that 13 % of the remaining vegetation coverage in the study area is in risk. In general, road density and size of human population are important variables related to fragmentation (Laurance et al. 2002). For example, roads are significant landscape modifications and are considered deforestation agents that accelerate fragmentation, reduce the regeneration of the forests, and are a threat for many tropical ecosystems and for the distribution of specialized species (e. g. Young 1994; Fearnside 2007; Freitas et al. 2010). They frequently increase slope instability, they allow the unregulated extraction of natural resources and the transformation of the landscape (Young 1994). The new Rioverde-Cd. Valles highway goes through CH and GSP in the areas with the best potential habitat for margays, which poses a new threat. Roads and related disturbances have a noticeable and well-recorded impact on wild felines (Van Dyke et al. 1986; Beldon and Hagedorn 1993; Beier 1995; Lovallo and Anderson 1996; Tewes and Blanton 1998; Tuovila 1999; Tewes and Hughes 2001). Unless there are more efforts to improve the design, construction and maintenance of the roads, as well as to understand and mitigate their effects, several carnivore species (e. g. Noss et al. 1996; Ruediger 1996), and specialized montane forest biota (Young 1994) may decline or disappear.

For this study, the reliable distribution area of the presence of margays was restricted to the Northeastern portion of its global distribution. It is crucial to stress the importance of preserving the landscape structure as along with the juxtaposition of spatial elements and connectivity for the conservation of species (e. g. Danielson 1994; Gehring 2000). Conservation must begin with habitat protection and restoration (e. g. Danielson 1994; Fahrig 1997), so the connection between GSP and CH is of vital importance to the preservation of margays in the long term. One alternative to mitigate some of the effects of fragmentation, and to compromise with the need for agricultural production, is the plantation of forests with non-native species. This can also aid in the conservation of some non-flying mammals, thus collaborating in the conservation of the local biodiversity (Martin et al. 2012). In this sense, fruit gardens or timberlands may be more suitable than annual crops because they provide better habitat for adaptable species, including margays. Furthermore, these new farming areas could use native vegetation as a buffer zones.

This study provides enough accurate information regarding the fundamental aspects of the habitat and essential needs of the margay to lay the foundation of an effective management plan in Northeastern Mexico. The involvement of government entities and the public is essential for the implementation of these new management plans. Conserving this carnivore will also improve the conservation of many other valuable species, as well as their ecosystem and environmental services.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)