Articles

A Review of Road-killed Felids in Mexico

-

Publication dates-

May-Jun , 2018

Electronic publication (usually web, but also includes CD-ROM or other electronic only distribution) - Article in PDF

- Article in XML

- Automatic translation

- Send this article by e-mail

- Share this article +

Abstract:

Six species of felids are distributed across Mexico and all are affected to a greater or lesser extent by the national highway network (377,660 km in length), but the magnitude of its impact on these species is unknown. Part of the issue is the scarce information available spread across the scientific literature, mammal collections records, environmental consultancies, and the local press. This work compiled the information available on road-killed felids in Mexico and organizes it systematically to identify potential data trends. We conducted a systematic search for records of verified felid roadkill events across Mexico reported in the scientific literature, mammal collections, online news and emails addressed to mammal -- particularly wild cat -- management/conservation specialists. First, felid roadkill records were entered and classified according to origin, i.e. source of information, and then classified according to the state where the event occurred. This information was used to explore the potential correlation between felid roadkill frequency and road density per state. Roadkill events were reported for all felid species, with a total of 115 records in 25 states: Herpailurus yagouaroundi, 21; Leopardus pardalis, 20; L. wiedii, 11; Lynx rufus, 50; Puma concolor, 5; and Panthera onca, 8. Most of the information came from mammal collections (40 records), followed by personal communications (25), and publications in local media (19), citizen science websites (10), peer-reviewed journals (9), non-governmental organizations (7), and government agencies (5). We found a significant correlation between road density and number of roadkill events recorded per state. Road density alone is insufficient to explain some geographic bias in felid roadkill data, which might instead be related to the appeal of a species, and to being recorded by people (scientists or otherwise) interested in this issue in a particular location. Acknowledging road mortality as an issue for felids in our country might contribute to identify and apply methods to improve data collection (citizen science) to develop preventive measures in our highways (wildlife crossing structures), particularly in wildlife high-risk areas.

Key words::

Felines, highways, mortality, roads

Introduction

The quantity and quality of the road infrastructure are key economic growth drivers, facilitating access of inhabitants to health and education services, besides contributing to reduce poverty (Bird et al. 2011). In Mexico, investment in road infrastructure is considered a strategic issue, since it fosters economic growth and development. It is one of the cornerstones of competitiveness and social well-being, supporting economic growth and regional development, and reducing transportation costs (Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 2014). However, roads involve multiple negative environmental effects, including pollution, habitat fragmentation, and deforestation, as well as wildlife mortality from roadkill events (Forman et al. 2003).

-

Bird et al. 2011Isolation and poverty—the relationship between spatially differentiated access to goods and services and poverty. Overseas Development Institute (ODI), ODI Working paper, 2011

-

Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 2014Programa Nacional de Infraestructura 2014-2018, 2014

-

Forman et al. 2003Road Ecology Science and Solutions, 2003

In particular, wild cats are affected to a large extent by roads (Kerley et al. 2002; Ngoprasert et al. 2007; Ford et al. 2010; Jansen et al. 2010; McGuire 2012; Basille et al. 2013), as these mammals typically have large home ranges and roam long distances (Macdonald et al. 2010b), in addition to being low tolerant to human disturbance (Macdonald et al. 2010a). These attributes increase the vulnerability of these species to the effects of roads and traffic (Grilo et al. 2015). Mortality associated to road collisions has been reported for several felids [e.g. tiger (Panthera tigris) Gruisen 1998a, b; lion (Panthera leo) Drews 1995; Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) Simon et al. 2012], leading to significant effects on the conservation of some species such as the Iberian lynx and subspecies as the Florida puma (Puma concolor coryi: Taylor et al. 2002).

-

Kerley et al. 2002Effects of roads and human disturbance on Amur tigersConservation Biology, 2002

-

Ngoprasert et al. 2007Human disturbance affects habitat use and behavior of Asiatic leopard Panthera pardus in Kaeng Krachan National Park, ThailandOryx, 2007

-

Ford et al. 2010The Banff wildlife crossings project: An international public-private partnershipSafe passages, 2010

-

Jansen et al. 2010The I-75 Project: Lessons from the Florida PantherSafe Passages: highways, wildlife and habitat connectivity, 2010

-

McGuire 2012No ordinary highway: A thirty-year retrospective, Trans-Canada Highway, Banff National Park of CanadaRethinking protected areas in a changing world: Proceedings of the 2011 George Wright Society Conference on Parks, Protected Areas, and Cultural Sites, 2012

-

Basille et al. 2013Selecting habitat to survive: the impact of road density on survival in a large carnivorePlos ONE, 2013

-

Macdonald et al. 2010bFelid societyBiology and conservation of wild felids, 2010

-

Macdonald et al. 2010aFelid futures: crossing disciplines, borders and generationsBiology and conservation of wild felids, 2010

-

Grilo et al. 2015Carnivores: Struggling for survival in roaded landscapesHandbook on Road Ecology, 2015

-

Gruisen 1998aRajasthanTiger Link, 1998

-

bUttar PradeshTiger Link, 1998

-

Drews 1995Road kill of animals by public traffic in Mikumi National Park, Tanzania with notes on baboon mortalityAfrican Journal of Ecology, 1995

-

Simon et al. 2012Reverse of the decline of the endangered Iberian lynxConservation Biology, 2012

-

Taylor et al. 2002Causes of mortality of free ranging Florida panthersJournal of Wildlife Diseases, 2002

Mexico is home to six felid species: Herpailurus yagouaroundi (jaguarundi), Leopardus pardalis (ocelot), L. wiedii (margay), Lynx rufus (bobcat), Puma concolor (puma) and Panthera onca (jaguar; Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2014). The effect of roads on felids has focused on the jaguar, both in Mexico and throughout its distribution range, finding that these negatively affect its mobility and dispersal (Ortega-Huerta and Medley 1999; Conde 2007; Conde et al. 2010; Colchero et al. 2011; Pallares et al. 2015; Stoner et al. 2015; Cullen et al. 2016; Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017). At the continental level and particularly in Mexico, P. concolor and H. yagouaroundi are considered to be species exposed to high road densities, and hence to their negative effects, including death by vehicle collision (Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017). For L. pardalis, L. wiedii and L. rufus there are no specific data on the potential effect of roads on their populations in Mexico.

-

Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2014List of recent land mammals of MexicoSpecial Publications Museum of Texas Tech University, 2014

-

Ortega-Huerta and Medley 1999Landscape analysis of jaguar (Panthera onca) habitat using sighting records in the Sierra de Tamaulipas, MexicoEnvironmental Conservation, 1999

-

Conde 2007Análisis Ambiental y Económico de Proyectos Carreteros en la Selva Maya, un Estudio a Escala Regional, 2007

-

Conde et al. 2010Sex matters: modeling male and female habitat differences for jaguar conservationBiological Conservation, 2010

-

Colchero et al. 2011Jaguars on the move: modeling movement to mitigate fragmentation from road expansion in the Mayan ForestAnimal Conservation, 2011

-

Pallares et al. 2015Case study: Roads and Jaguars in the Mayan ForestsHandbook on Road Ecology, 2015

-

Stoner et al. 2015Conectividad entre Hábitats del Jaguar e Identificación de Lugares Potenciales de Mitigación de Impactos Carreteros en la Unidad de Recuperación Noroeste del Jaguar, 2015

-

Cullen et al. 2016Implications of Fine-Grained Habitat Fragmentation and Road Mortality for Jaguar Conservation in the Atlantic Forest, BrazilPLoS ONE, 2016

-

Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017Global exposure of carnivores to roadsGlobal Ecology and Biogeography, 2017

-

Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017Global exposure of carnivores to roadsGlobal Ecology and Biogeography, 2017

There are literature reports of roadkill events outside of Mexico involving the six felid species (e. g., H. yagouaroundi, Cunha et al. 2010; Hegel et al. 2012; Arias-Alzate et al. 2013; Giordano 2015; L. pardalis, Cáceres et al. 2010; L. wiedii, Carvalho et al. 2014; P. concolor, Maehr et al. 1991; Cáceres et al. 2010; P. onca, Srbek-Araujo et al. 2015). However, in Mexico no felids have been reported in publications addressing road-killed wildlife (see González-Gallina and Benítez-Badillo 2013); the few sporadic records come from studies on the distribution of species rather than the effect of roads as such (e. g., Meraz et al. 2010; Almazan-Catalan et al. 2013).

-

Cunha et al. 2010Roadkill of wild vertebrates along the GO-060 road between Goiânia and Iporá, Goiás State, BrazilActa Cientiarum Biological Sciences, 2010

-

Hegel et al. 2012Mamíferos silvestres atropelados na rodovia RS-135, norte do Estado do Rio Grande do SulBiotemas, 2012

-

Arias-Alzate et al. 2013Presencia de Puma yagouaroundi (Carnivora: Felidae) en el valle de Aburrá, Antioquia, ColombiaBrenesia, 2013

-

Giordano 2015Ecology and status of the jaguarondi Puma yagouaroundi: a synthesis of existing knowledgeMammal Review, 2015

-

Cáceres et al. 2010Mammal occurrence and roadkill in two adjacent ecoregions (Atlantic Forest and Cerrado) in south-western BrazilZoologia, 2010

-

Carvalho et al. 2014Large and medium-sized mammals of Carajás National Forest, Pará state, BrazilCheck List, 2014

-

Maehr et al. 1991Social ecology of Florida panthersNational Geographic Research and Exploration, 1991

-

Cáceres et al. 2010Mammal occurrence and roadkill in two adjacent ecoregions (Atlantic Forest and Cerrado) in south-western BrazilZoologia, 2010

-

Srbek-Araujo et al. 2015Jaguar (Panthera onca Linnaeus, 1758) roadkill in Brazilian Atlantic Forest and implications for species conservationBrazilian Journal of Biology, 2015

-

González-Gallina and Benítez-Badillo 2013The small, the forgotten and the dead: highway impact on vertebrates and its implications for mitigation strategiesBiodiversity and Conservation, 2013

-

Meraz et al. 2010El Ocelote (Leopardus pardalis) y Tigrillo (Leopardus wiedii) en la costa de OaxacaCiencia y Mar, 2010

-

Almazan-Catalan et al. 2013Registros adicionales de felinos del estado de Guerrero, MéxicoRevista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 2013

At the global level, a large amount of information on roadkilled wildlife is available in informal information sources including news in the local press, anecdotal evidence or records in informal unpublished technical reports (Smith and van der Ree 2015), and more recently also in social websites (Shilling et al. 2015). No studies have been conducted to date to gather information from informal media such as citizen science websites to assess felid roadkill events in Mexican roads. In addition, despite the fact that information systems have been put in place in Mexico for the systematic recording of wildlife road kills (e. g., Naturalista by CONABIO http://www.naturalista.mx/ and Observatorio de Movilidad y Mortalidad de Fauna (Wildlife Mobility and Mortality Observatory) by SCT/IMT http://watch.imt.mx ), these have not been fully developed, unlike other countries (e. g., URUBU System in Brazil http://sistemaurubu.com.br/es/; California Roadkill Regitration System in USA http://www.wildlifecrossing.net/california/; Shilling et al. 2015).

-

Smith and van der Ree 2015Field methods to evaluate the impacts of roads on wildlifeHandbook on Road Ecology, 2015

-

Shilling et al. 2015Wildlife/Roadkill observation and reporting systemsHandbook on Road Ecology, 2015

-

Shilling et al. 2015Wildlife/Roadkill observation and reporting systemsHandbook on Road Ecology, 2015

The collection of information on the number of road-killed felids and the regions where these are killed in Mexico is of great importance for the conservation of these species, as four of the six felid species are listed in one of the protection categories established in the Mexican regulations (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010), and roadkill mortality adds to other anthropogenic causes (e .g., hunting, loss of habitat, human-carnivore conflicts, etc: CONANP 2009). From the above, the objective of this work was to carry out a review of the records regarding felid roadkill events in Mexico, from formal and informal sources, sorting them systematically according to their origin (time and place of occurrence).

-

CONANP 2009Programa de acción para la conservación de la especie: Jaguar (Panthera onca), 2009

Materials and Methods

Study Area. The survey of felid roadkill records comprised all mexican territory. The country has a road network of approximately 156,797 km (141,545 km of two-lane roads and 15,252 km of highways with more than two lanes; SCT 2016) traveled by a fleet of 27,500,000 vehicles (INEGI 2017). The distribution range of the six species of wild cats living in Mexico is very broad (Hall 1981), so that P. concolor is potentially found throughout the country, while P. onca, L. pardalis, L. wiedii and H. yagouaroundi are distributed in tropical areas, and L. rufus in mostly temperate areas.

-

SCT 2016Anuario estadístico Sector Comunicaciones y Transportes 2013-2018, 2016

-

INEGI 2017Estimación de cifras con base a las ventas reportadas por la Encuesta Mensual de la Industria Manufacturera (EMIM) y la AMIA, A.C, 2017

-

Hall 1981The mammals of North America, 1981

Methods. Information on felid roadkill events in Mexico was obtained through a systematic search of confirmed records of wild cats killed by cars in Mexico in the scientific literature, mammal collection records, online news, and emails addressed to specialists in conservation and management of mammals, especially wild cats. The information gathered from each of the records of road-killed felids included species, road or town closest to the collision site, state of Mexico where the incident occurred, year, type of information source, and reference. The survey aimed at obtaining an annual overview of the sources of these records, discarding those with uncertain date. Two types of information sources were surveyed, i. e. published and non-published; the first can be consulted and the second has added reliability through consultation with specialists. Within these two categories, the following media were searched:

Scientific literature. The survey included published articles and theses using specialized webpages like Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.com.mx) and Web of Science (https://www.webofknowledge.com/). In each of these sites, the search criteria used were the felid species (common and scientific name) and the word hit/struck/road-killed in both English and Spanish. Once a record was identified, this was reviewed to determine the type of record. A felid roadkill record was deemed valid if it explicitly referred to the record of a hit animal, in addition to providing specific information on place and date. In the case of bachelors or graduate theses, the record was determined as valid only when a photograph of the struck specimen was included, provided the author could confirm the cause of death.

Mammal Collections and Citizen Science websites. Information was requested from curators of 28 collections listed in the Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología A. C. (Lorenzo et al. 2006), particularly regarding collection site and year of recording, about any of the six Mexican wild cat species that were collected and deposited in the collection after being hit. Also, each field record in the NaturaLista webpage (http://www.naturalista.mx/) was reviewed to identify the road-killed specimens.

-

Lorenzo et al. 2006Colecciones mastozoológicas de México, 2006

Internet media. The Google web browser (http://www.google.com) was extensively surveyed for informal published records of road-killed felids (e. g., news about specific roadkill events mentioned in national or local news media, personal web pages or social networks, and reports from the web pages of non-governmental organizations). The search was conducted using the following key words: common name + road-killed, species + road-killed, common name + Mexico, species + Mexico, species + road, common name + road, in both Spanish and English. Once a record was identified, the original source was reviewed, and the quality of the information assessed based on the presence/absence of photographs of the event, as well as its geographic location.

Emails addressed to specialists (personal communications). Through e-mails sent to specialists in wild cats and wildlife conservation in Mexico working in Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), universities and government authorities, information was requested on specific events involving struck felids that these specialists witnessed or on which they had specific information. Once the specialist was contacted, specific data were requested regarding species, year and location of the roadkill event, as well as any photograph of it, if available. These records were classified into personal communications or obtained from a NGO.

Data Analysis. The records of road-killed felids were entered into a database by species in phylogenetic order (Prevosti et al. 2010) and classified first by origin, in accordance with the source of information (scientific literature, collections, online news or specialists). From the geographical standpoint, records were classified according to the state where the roadkill event occurred. It was decided that the analysis would be conducted by state, since many of the observations (from published and unpublished sources) had no precise data of the specific locality or road segment where the event occurred.

-

Prevosti et al. 2010Morfología craneana en tigres dientes de sable: alometría, función y filogeniaAmeghiniana, 2010

The first stage of the analysis compared roadkill data (dates and sites) obtained from the various sources of information, in order to identify potential duplicate records. Subsequently, it was investigated whether the felid roadkill sites matched the distribution range of the species in Mexico. To this end, the presence/absence of felid roadkill events obtained from all information sources in each state of the country was determined by species and compared in a Geographical Information System versus the range reported for the respective species (Hall 1981) from the Digital Distribution Maps of the Mammals of the Western Hemisphere v. 3.0 (Patterson et al. 2007).

-

Hall 1981The mammals of North America, 1981

-

Patterson et al. 2007Digital Distribution Maps of the Mammals of the Western Hemisphere, 2007

The next stage of the analysis was to determine whether felid roadkill events are related to road density. A positive relationship between road density in a region and the number of medium-sized mammal roadkill events has been observed (Saeki and Macdonald 2004). In Mexico, the national road network is not evenly distributed; instead, important regional differences occur in the density of roads across the different states of the country (Deichmann et al. 2004). The surface area in km2 (INEGI 2015) and the length of roads (km) in state were obtained (SCT 2016). Road density per state was calculated by dividing the total number of km of roads by the surface area of each state. The relationship between road density and the number of felid roadkill records per state was investigated through a Spearman’s rank correlation (Siegel and Castellan 1988); road density per state was associated with the number of felid roadkill events for each state considering all the sources of information used.

-

Saeki and Macdonald 2004The effects of traffic on the raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides viverrinus) and other mammals in JapanBiological Conservation, 2004

-

Deichmann et al. 2004Economic structure, productivity, and infrastructure quality in southern MexicoThe Annals of Regional Science, 2004

-

INEGI 2015Anuario estadístico y geográfico por entidad federativa 2015, 2015

-

SCT 2016Anuario estadístico Sector Comunicaciones y Transportes 2013-2018, 2016

-

Siegel and Castellan 1988Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences, 1988

We analyze the data on an annual basis according to the source of information, to identify any changes in the trends in data recording during the period covered by the study. We excluded from the analysis those years were information was not available.

Results

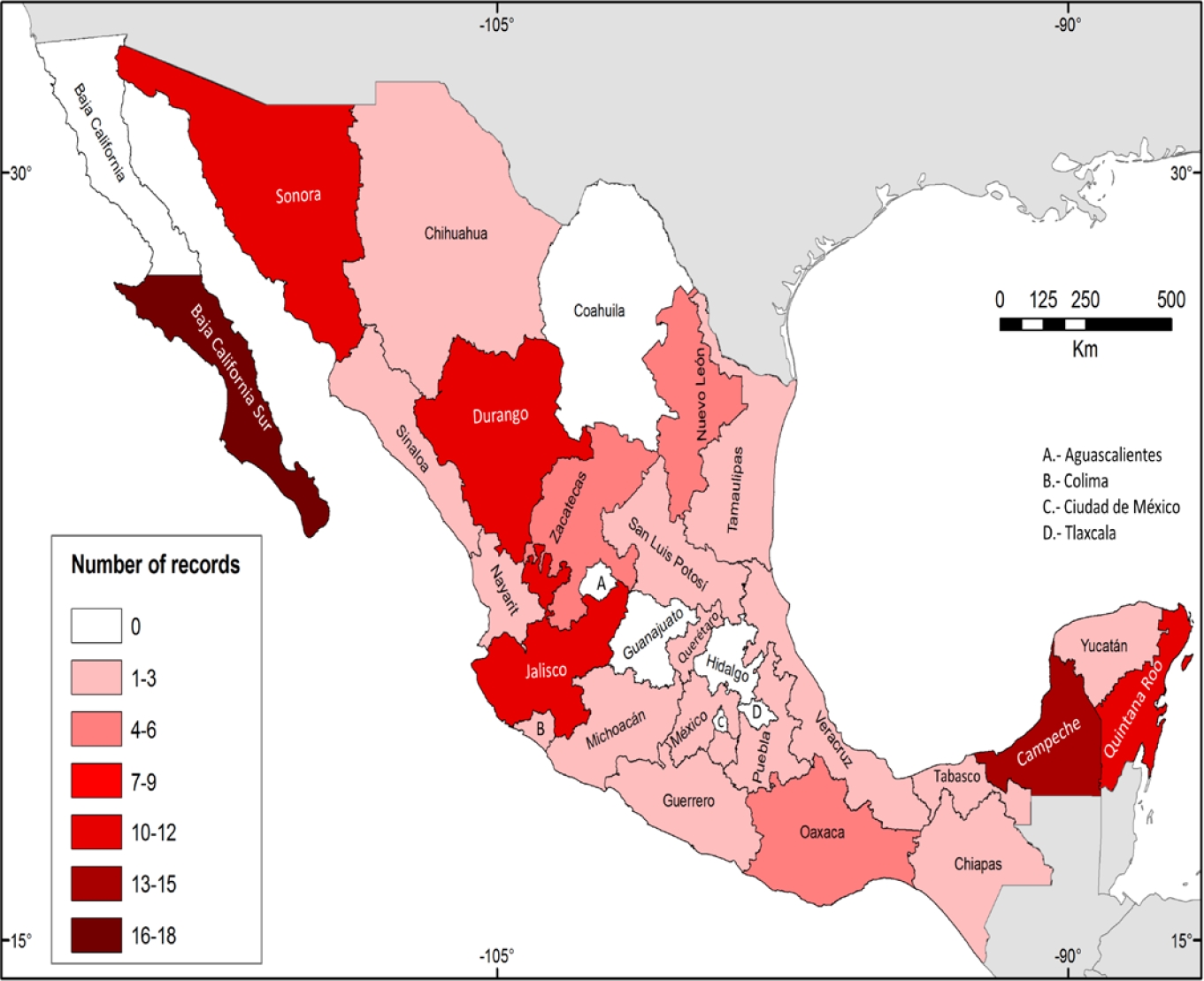

The review revealed the existence of records of road killedfelids dating back to 1982. A total of 115 records of roadkill events was found for the six felid species living in Mexico (Supplementary Material 1, Figure 1). The number of roadkill records found were: H. yagouaroundi, 21; L. pardalis, 20; L. wiedii, 11; L. rufus, 50; P. concolor, 5; and P. onca, 8 (Figure 2). Of all records, 90 came from publications (academic and news, 78.2 %) and 25 were obtained through personal communications (21.7 %). Within published news (online or printed), 40 (34.8 %) came from scientific collections, 9 (16.5 %) from the local press, 10 from citizen science through CONABIO’s Naturalista webpage (8.7 %), nine (7.8 %) from peer-reviewed publications, seven (6.1 %) from NGOs, and five (4.3 %) from government agencies (Table 1).

Thumbnail

Figure 1

Total number of records of felid roadkill events in Mexico by state. The figure includes the sum of records of Herpailurus yagouaroundi, Leopardus pardalis, L. wiedii, Lynx rufus, Puma concolor and Panthera onca obtained from published (mammal collections, scientific literature, government, citizen science web page, NGOs, digital news) and unpublished sources (personal communication with experts in wild cat conservation) from 1982 to 2017.

Total number of records of felid roadkill events in Mexico by state. The figure includes the sum of records of Herpailurus yagouaroundi, Leopardus pardalis, L. wiedii, Lynx rufus, Puma concolor and Panthera onca obtained from published (mammal collections, scientific literature, government, citizen science web page, NGOs, digital news) and unpublished sources (personal communication with experts in wild cat conservation) from 1982 to 2017.

Thumbnail

Figure 2

a) Specimen of Herpailurus yagouaroundi recorded on La Ventosa road, Oaxaca. Photograph: Alejandro Tepatlán Vargas. b) Specimen of Herpailurus yagouaroundi recorded on the Tizimín road, Yucatán. Photograph: Diana F. Zamora Bárcenas. c) Specimen of Leopardus pardalis recorded near the Federal Highway 85, Ejido Miguel Hidalgo, Tamaulipas. Photograph: Milton Gildardo Ruiz-Bautista. d) Specimen of Leopardus pardalis in the Puerto Morelos - Playa del Carmen road. Photograph: Victor Castelazo-Calva. e) Specimen of Leopardus wiedii recorded near the Federal Highway 74 in Nayarit. Photograph: Mark Stackhouse. f) Specimen of Lynx rufus on a road in the border between the states of Queretaro and Guanajuato. Photograph: Diana F. Zamora Bárcenas. g) Specimen of Lynx rufus in the Federal Highway 7D El Sueco, Chihuahua. Photograph: Mircea Hidalgo Mihart. h) Runover specimen of Panthera onca near the Sabancuy-Champoton road, Campeche. Photograph: Marco Sánchez (CONANP, Laguna de Términos).

a) Specimen of Herpailurus yagouaroundi recorded on La Ventosa road, Oaxaca. Photograph: Alejandro Tepatlán Vargas. b) Specimen of Herpailurus yagouaroundi recorded on the Tizimín road, Yucatán. Photograph: Diana F. Zamora Bárcenas. c) Specimen of Leopardus pardalis recorded near the Federal Highway 85, Ejido Miguel Hidalgo, Tamaulipas. Photograph: Milton Gildardo Ruiz-Bautista. d) Specimen of Leopardus pardalis in the Puerto Morelos - Playa del Carmen road. Photograph: Victor Castelazo-Calva. e) Specimen of Leopardus wiedii recorded near the Federal Highway 74 in Nayarit. Photograph: Mark Stackhouse. f) Specimen of Lynx rufus on a road in the border between the states of Queretaro and Guanajuato. Photograph: Diana F. Zamora Bárcenas. g) Specimen of Lynx rufus in the Federal Highway 7D El Sueco, Chihuahua. Photograph: Mircea Hidalgo Mihart. h) Runover specimen of Panthera onca near the Sabancuy-Champoton road, Campeche. Photograph: Marco Sánchez (CONANP, Laguna de Términos).

Table 1

Number of records of the six wild cat species struck in Mexico, classified according to the source of the record. Mammal Collection (MC), scientific literature (SL), citizen science web page (CSW), report in government media (RGM), digital news (DN), non-governmental organization (NGO), personal communication (PC).

Number of records of the six wild cat species struck in Mexico, classified according to the source of the record. Mammal Collection (MC), scientific literature (SL), citizen science web page (CSW), report in government media (RGM), digital news (DN), non-governmental organization (NGO), personal communication (PC).

| Source of the record | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | MC | SL | CSW | RGM | DN | NGO | PC | Total |

| Herpaiulurus yagouaroundi | 3 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 21 |

| Leopardus pardalis | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 20 |

| Leopardus wiedii | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| Lynx rufus | 28 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 50 |

| Puma concolor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Panthera onca | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| Total (% of total) | 40 (34.78 %) | 9 (7.83 %) | 10 (8.70 %) | 5 (4.35 %) | 19 (16.52 %) | 7 (6.09 %) | 25 (21.74 %) | 115 |

Roadkill events were recorded in 25 of the 32 states of Mexico (Table 2, Figure 1). The comparison of the distribution area with the location of roadkill records for a given species reveals that there are states with no roadkill reports in spite of being included in the distribution range of the species (Figure 4). Roadkill events reported are as follows: H. yagouaroundi, 10 of the 15 states where it lives (10/15; 45 %); L. pardalis, 10/25 states (40 %); L. wiedii, 7/20 (35 %); and L. rufus, 11/27 (41 %). In the case of P. concolor, although this species is distributed throughout all of Mexico, roadkill events are recorded in three states only (Jalisco, Durango and Sonora, 9.4 %). Events involving P. onca are reported in four (Quintana Roo, Campeche, Veracruz, and Jalisco) of the 27 states where the species is distributed (15 %).

Table 2

Roadkill records by species and distribution range of the respective species in each state of Mexico. Roadkill records for each species were obtained from published (90) and unpublished sources (25). The presence of the species in each state was obtained from overlapping Hall’s distribution polygons (Hall 1981) for each species on the political division map of the Mexican Republic. The letter “P” indicates that the species is present in the state. “A” indicates that there are roadkill records for the species in the state. As regards the number of species per state, the first column corresponds to the presence and the second to records of struck species.

Roadkill records by species and distribution range of the respective species in each state of Mexico. Roadkill records for each species were obtained from published (90) and unpublished sources (25). The presence of the species in each state was obtained from overlapping Hall’s distribution polygons (Hall 1981) for each species on the political division map of the Mexican Republic. The letter “P” indicates that the species is present in the state. “A” indicates that there are roadkill records for the species in the state. As regards the number of species per state, the first column corresponds to the presence and the second to records of struck species.

| State | Herpailurus yagouaroundi | Leopardus pardalis | Leopardus wiedii | Lynx rufus | Puma concolor | Panthera onca | Number of species per state | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguascalientes | P | P | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Baja California | P | P | P | 3 | 0 | |||||||||

| Baja California Sur | P | A | P | 2 | 1 | |||||||||

| Campeche | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 5 | 4 | |||

| Chiapas | P | A | P | P | P | P | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| Chihuahua | P | P | P | A | P | P | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| Coahuila | P | P | P | P | 4 | 0 | ||||||||

| Colima | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Ciudad de México | P | P | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Durango | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Estado de México | P | A | P | P | P | P | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| Guanajuato | P | P | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Guerrero | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Hidalgo | P | P | P | P | P | 5 | 0 | |||||||

| Jalisco | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | 6 | 6 |

| Michoacán | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | 6 | 3 | ||||

| Morelos | P | P | P | A | P | P | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| Nayarit | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Nuevo León | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Oaxaca | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | P | P | 6 | 3 | |||

| Puebla | P | P | P | P | A | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Querétaro | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Quintana Roo | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 5 | 3 | ||||

| San Luis Potosí | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Sinaloa | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Sonora | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Tabasco | P | A | P | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | ||||||

| Tamaulipas | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Tlaxcala | P | P | P | P | 4 | 0 | ||||||||

| Veracruz | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | A | 6 | 3 | |||

| Yucatán | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Zacatecas | P | A | P | P | 3 | 1 | ||||||||

| Total | 22 | 10 | 25 | 10 | 20 | 7 | 27 | 11 | 32 | 3 | 27 | 4 | ||

-

Hall 1981The mammals of North America, 1981

Thumbnail

Figure 3

Records of each of the road-killed felid species in Mexico by state, showing the distribution range of each species from Hall (1981; in gray). Sum of records for each species obtained from published (scientific literature, mammal collections, digital news, government, citizen science portal or NGO websites) and unpublished sources (personal communication with experts in wild cat conservation) from 1982 to 2017. a) Herpailurus yagouaroundi, b) Leopardus pardalis, c) Leopardus wiedii, d) Lynx rufus, e) Puma concolor, and f) Panthera onca.

Records of each of the road-killed felid species in Mexico by state, showing the distribution range of each species from Hall (1981; in gray). Sum of records for each species obtained from published (scientific literature, mammal collections, digital news, government, citizen science portal or NGO websites) and unpublished sources (personal communication with experts in wild cat conservation) from 1982 to 2017. a) Herpailurus yagouaroundi, b) Leopardus pardalis, c) Leopardus wiedii, d) Lynx rufus, e) Puma concolor, and f) Panthera onca.

Thumbnail

Figure 4

Number of records of road-killed felids according to their origin as obtained from published (scientific literature, mammal collections, digital news, government, citizen science portal or NGO websites) and unpublished sources (personal communication with experts in wild cat conservation).

Number of records of road-killed felids according to their origin as obtained from published (scientific literature, mammal collections, digital news, government, citizen science portal or NGO websites) and unpublished sources (personal communication with experts in wild cat conservation).

An inverse relationship was observed between road density by state and number of felid roadkill events registered (Rho=-0.35658, P = 0.04515). I. e. a lower road density is apparently associated with more events. Examples are Baja California Sur, with a road density of 0.8 km/km2 and 18 records; and Tlaxcala, with a high road density of 0.73 km/km2 and no roadkill records. Not all states show this same behavior, such as Chihuahua, with the lowest road density (0.05 km/km2) and no roadkill records, or Jalisco, with a road density of 0.36 km/km2 and 10 roadkill records.

The analysis of roadkill records and their sources (Figure 4) was conducted with 109 accurately dated records (6 records with no date were excluded). The period 1982-2017, comprising 35 years, included 21 years with roadkill records. The period 1982-2006 reported 25 felid roadkill records, 88 % from collections and scientific literature and the rest from personal communications. From 2007 to date 84 records were reported, 27.4 % from a collection or the scientific literature, and 72.6 % from other sources (22.6 %, online news; 26.2 %, personal communications).

Discussion

Among mammals, carnivores are the group most adversely affected by roadkill events (Rytwinski and Fahrig 2015; Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017), with well-documented cases, particularly in wild cats (e. g., Ferreras et al. 1992; Taylor et al. 2002). In Mexico, up until this report, no estimates of the number of roadkill events involving wild cats in the country was available to document the potential impact of this phenomenon on the conservation of the species. However, we now know that at least 115 individuals of the six species were killed by vehicle collision events between 1982 and 2017.

-

Rytwinski and Fahrig 2015The impacts of roads and traffic on terrestrial animal populationsHandbook on Road Ecology, 2015

-

Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017Global exposure of carnivores to roadsGlobal Ecology and Biogeography, 2017

-

Ferreras et al. 1992Rates and causes of mortality in a fragmented population of Iberian Lynx Felis pardina Temminck, 1824Biological Conservation, 1992

-

Taylor et al. 2002Causes of mortality of free ranging Florida panthersJournal of Wildlife Diseases, 2002

No records involving wild cats are reported in specific works on the quantification of roadkill events in Mexico (González-Gallina and Benítez-Badillo 2013), suggesting sporadic collision of these species by vehicles. However, despite the important efforts carried out in studies about animals killed on mexican roads, these have focused on a few road stretches and involving short periods of time (e .g., Morales-Mavil et al. 1997; Grosselet et al. 2008; González-Gallina et al. 2013; Pacheco-Figueroa et al. 2013), hence limiting its impact when seeking to understand the dynamics of this phenomenon at the national level (González-Gallina and Benítez-Badillo 2013). The information survey in different media allowed to establish the incidence of this phenomenon despite the absence of reports specifically mentioning felids in formal road surveys. This work points to the states where this type of studies should be conducted to gather further information.

-

González-Gallina and Benítez-Badillo 2013The small, the forgotten and the dead: highway impact on vertebrates and its implications for mitigation strategiesBiodiversity and Conservation, 2013

-

Morales-Mavil et al. 1997Mortalidad de vertebrados silvestres en una carretera asfaltada de la región de Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, MéxicoCiencia y el Hombre-UV, 1997

-

Grosselet et al. 2008Afectaciones a vertebrados por vehículos automotores en 1.2 km de carretera en el Istmo de Tehuantepec in Proceedings of the Fourth International Partners in Flight ConferenceTundra to Tropics, 2008

-

González-Gallina et al. 2013The small, the forgotten and the dead: highway impact on vertebrates and its implications for mitigation strategiesBiodiversity and Conservation, 2013

-

Pacheco-Figueroa et al. 2013Mortalidad de fauna en carreteras de la zona costera tabasqueñaPerspectiva Científica desde la UJAT, 2013

-

González-Gallina and Benítez-Badillo 2013Road ecology studies for México: a reviewOecología Australis Special issue on Road Ecology, 2013

It has been proposed that the vulnerability of wildlife species such as felids increases directly with road density (Cullen et al. 2016). Particularly for Mexico, the northeast and south-southeast regions of the country were identified as areas where several species of wild cats are exposed to high road densities (Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017). Despite the above, there are states for which just a few roadkill events, if any, have been reported, despite the fact that extensive areas of their territories are part of the distribution range of several species (e. g., Coahuila and Baja California), while others report a high number of struck specimens (i. e., Baja California Sur) in spite of the low road density (0.08 km/km2). This parameter alone does not entirely explain the distribution of roadkill records. Another factor affecting this distribution relates to the existence of professionals or institutions interested in keeping records of roadkill events. Mammal collections were the main source of felid roadkill records (34.8 % of the total number of records), the states with the highest number of records being those associated with a scientific collection, mostly when it focuses on the study of the local or regional fauna. This is the case of the comparison between the records in Baja California Sur (road density 0.08 km/km2) and Baja California (0.17 km/km2). Baja California Sur reports the largest number of wild cat roadkill events, with all records coming from the mammal collection of the Centro de Investigaciones del Noroeste (CIBNOR), while Baja California, in spite of sharing many of the ecological and environmental conditions with the neighboring state (Morrone and Márquez 2003), has no records of struck felids, probably because there are no groups of professionals interested in the subject.

-

Cullen et al. 2016Implications of Fine-Grained Habitat Fragmentation and Road Mortality for Jaguar Conservation in the Atlantic Forest, BrazilPLoS ONE, 2016

-

Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017Global exposure of carnivores to roadsGlobal Ecology and Biogeography, 2017

-

Morrone and Márquez 2003Aproximación a un Atlas Biogeográfico Mexicano: Componentes bióticos principales y provincias biogeográficasUna perspectiva latinoamericana de la biogeografía, 2003

Our results showed that 72.2 % of the records came from published sources available for consultation through formal searches (mammal collections or scientific publications); this finding strengthens the proposal that as regards roadkill events, information surveys should always involve information from non-formal sources (Smith and van der Ree 2015). However, although many of the records of road-killed felids in Mexico referred to H. yagouaroundi, L. rufus and P. concolor (65.2 % of records), in less formal media — particularly online media — a high percentage of the records (73.7 %) are related to L. pardalis, L. wiedii, and P. onca. This can be explained by the fact that there are animal species that capture the attention of the public (Clucas et al. 2008). This is the case of wild cats with stripped or spotted fur (e. g., L. pardalis, L. wiedii and P. onca), which are conspicuous and are part of the Mexican culture and traditions (Saunders 2005), added to the fact that governmental and non-governmental organizations have disseminated their importance and conservation status (SEMARNAT 2009). This is the case of the jaguar, a species that recorded five roadkill records in the state of Quintana Roo (Supplementary Material 1) from news media and that has been followed up for being a species with public appeal, i. e. a news target.

-

Smith and van der Ree 2015Field methods to evaluate the impacts of roads on wildlifeHandbook on Road Ecology, 2015

-

Clucas et al. 2008Flagship species on covers of US conservation and nature magazinesBiodiversity and Conservation, 2008

-

Saunders 2005El icono Felino en México: Fauces, garras y uñasArqueología Mexicana. 2005. Arqueología Mexicana. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. México, 2005

-

SEMARNAT 2009Programa de Acción para la Conservación de la Especie: Jaguar (Panthera onca), 2009

The growth of electronic and online media, as well as the use of smartphones, has facilitated the spreading of news on wildlife roadkill events (Shilling et al. 2015). In this work, we observed a steady increase in the number of felid roadkill records over the past 10 years, with the largest growth in records in digital news. The growth in the number of smartphone users (from 50.6 million users in 2015 to 60.6 million in 2016; INEGI 2016), coupled with the creation of specific platforms for the recording of roadkill incidents — such as Fauna Silvestre Atropellada y Fauna Atropellada del Noreste (Road-killed Wildlife and Northeastern Road-killed Wildlife) available in the NaturaLista platform, or the Observatorio de Movilidad y Mortalidad de Fauna (Observatory of Wildlife Mobility and Mortality) —, promote the recording of a growing number of reports, as has happened in other countries (Olson et al. 2014; Vercayie and Herremans 2015; Shilling et al. 2015). In this work, only 8.7 % of the records of road-killed cats came from citizen science projects. The advancement of information systems through these projects would facilitate the registration on roadkill events, not only of felids but also of other wild mammal species at the country level. The ease of communication by electronic means may potentially improve data quality in the monitoring of roadkill events by professionals (Olson 2014), provided the analyses consider the limitations that are intrinsic to the type of information collected (e. g., variable sampling effort, bias toward larger and more visible species, among others; Sarda-Palomera et al. 2012).

-

Shilling et al. 2015Wildlife/Roadkill observation and reporting systemsHandbook on Road Ecology, 2015

-

INEGI 2016Encuesta Nacional sobre Disponibilidad y Uso de Tecnologías de la Información en los Hogares 2016, 2016

-

Olson et al. 2014Monitoring Wildlife-Vehicle Collisions in the Information Age: How Smartphones Can Improve Data CollectionPLoS One, 2014

-

Vercayie and Herremans 2015Citizen science and smartphones take roadkill monitoring to the next levelNature Conservation, 2015

-

Shilling et al. 2015Wildlife/Roadkill observation and reporting systemsHandbook on Road Ecology, 2015

-

Olson 2014Monitoring Wildlife-Vehicle Collisions in the Information Age: How Smartphones Can Improve Data CollectionPLoS One, 2014

-

Sarda-Palomera et al. 2012Fine-scale birds monitoring from light unmanned aircraft systemsIbis, 2012

This work shows that data on road-killed wild cats is an underestimation, since a large number of these events are not recorded. It is therefore imperative to determine whether this type of events affects the different wild cat species at the population level to the extent that may threaten their long-term survival. The majority of wild cat species are listed in a risk category (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010), and several are considered as in danger of extinction (L. pardalis, L. wiedii and P. onca). Collisions with vehicles add to other mortality factors such those coming from habitat loss or conflicts with livestock (CONANP 2009), and could be even more important (Simon et al. 2012, Taylor et al. 2002). The surveillance of roadkill events through systematic long-term monitoring may lead to more effective mitigation measures (Grilo et al. 2015). This work should serve as a forewarning to stimulate the development of monitoring efforts and appropriate mitigation measures for these animals at the national level.

-

CONANP 2009Programa de acción para la conservación de la especie: Jaguar (Panthera onca), 2009

-

Simon et al. 2012Reverse of the decline of the endangered Iberian lynxConservation Biology, 2012

-

Taylor et al. 2002Causes of mortality of free ranging Florida panthersJournal of Wildlife Diseases, 2002

-

Grilo et al. 2015Carnivores: Struggling for survival in roaded landscapesHandbook on Road Ecology, 2015

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff of the Mexican Mammal Collections for providing information about the specimens studied: C. Delfín-Alfonso of Biological Research at Universidad Veracruzana, Collection of Vertebrates (VER-MAM IIB-UV); S. T. Álvarez-Castañeda of the Mammal Collection at Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste (CIBNOR); O. G. Retana-Guiascon of the Mammal Collection at Universidad Autónoma de Campeche (CM-UAC); C. López-González at Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Scientific Wildlife Collection (CRD); A. F. Guzmán of the Osteological Collection, “M. en C. Ticul Álvarez Solórzano” Archaeozoology Laboratory at Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (DP), and F. A. Cervantes of the National Collection of Mammals (CNMA). To all the persons who facilitated their records and photographs to illustrate this work: A. González-Christen, A. McAndrews, A. Tepatlán-Vargas, J.C. Bravo, D. F. Zamora-Bárcenas, M. G. Ruiz-Bautista, M. Stackhouse R. Núñez-Pérez, and V. Castelazo-Calva. Thanks also to the Academic Division of Biological Sciences of Universidad Autónoma de Tabasco (DacBiol UJAT) and Instituto de Ecología, A.C. (INECOL) for participating in this work. This work was carried out by AGG in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree in Science from INECOL with support from CONACYT through scholarship 335814/232663. María Elena Sánchez-Salazar translated the manuscript into English.

Literature Cited

- Almazán-Catalán, J. A., C. Sánchez-Hernández, F. Ruíz-Gutiérrez, M. L. Romero-Almaraz, A. Taboada-Salgado, E. Beltrán-Sánchez, and L. Sánchez-Vázquez. 2013. Registros adicionales de felinos del estado de Guerrero, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 84:347-359. Links

- Arias-Alzate, A., C. A. Delgado-V, J. C. Ortega, S. Botero-Cañola, and J. D. Sánchez-Londoño. 2013. Presencia de Puma yagouaroundi (Carnivora: Felidae) en el valle de Aburrá, Antioquia, Colombia. Brenesia 79:83-84. Links

- Basille, M., B. Van Moorter, I. Herfindal, J. Martin, J. D. C. Linnell, J. Odden, R. Andersen, and J. M. Gaillard. 2013. Selecting habitat to survive: the impact of road density on survival in a large carnivore. Plos ONE 8: e65493.doi:10.1371/ journal. pone.0065493. Links

- Bird, K, A. McKay, and I. Shinyekwa. 2011. Isolation and poverty—the relationship between spatially differentiated access to goods and services and poverty. Overseas Development Institute (ODI), ODI Working paper 322:2011. London, UK. Links

- Brown, D. E., and C. A. López-González. 2001. Tigres de la Frontera. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, USA. Links

- Cáceres, N. C., W. Hannibal, D. R. Freitas, E. L. Silva, C. Roman, and J. Cadella. 2010. Mammal occurrence and roadkill in two adjacent ecoregions (Atlantic Forest and Cerrado) in south-western Brazil. Zoologia 27:709-717. Links

- Carvalho, A. S., F. D. Martins, F. Mendes-Dutra, D. Gettinger, F. Martins-Hatano, and H. G. Bergallo. 2014. Large and medium-sized mammals of Carajás National Forest, Pará state, Brazil. Check List 10:1-9. Links

- Ceia Hasse, A., L. Borda de Água, C. Grilo, and H. M. Pereira. 2017. Global exposure of carnivores to roads. Global Ecology and Biogeography 26:592-600. Links

- Clucas, B., K. McHugh, and T. Caro. 2008. Flagship species on covers of US conservation and nature magazines. Biodiversity and Conservation 17:1517–1528. Links

- Colchero, E., D.A Conde, C. Manterola, A. Rivera, and G. Ceballos. 2011. Jaguars on the move: modeling movement to mitigate fragmentation from road expansion in the Mayan Forest. Animal Conservation 14:158-166. Links

- Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP). 2009. Programa de acción para la conservación de la especie: Jaguar (Panthera onca). Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Distrito Federal, México. Links

- Conde, D. A., I. Burgués, L. Fleck, C. Manterola, and J. Reid. 2007. Análisis Ambiental y Económico de Proyectos Carreteros en la Selva Maya, un Estudio a Escala Regional. San Jose: Conservation Strategy Fund. Links

- Conde, D. A., F. Colchero, H. Zarza, N. L. Christensen, J. O. Sexton, C. Manterola, C. Chávez, A. Rivera, D. Azuara, and G. Ceballos. 2010. Sex matters: modeling male and female habitat differences for jaguar conservation. Biological Conservation 143:1980-1988. Links

- Cullen, L. Jr., J. C. Stanton, F. Lima, A. Uezu, M. L. L. Perilli, and H. R. Akcakaya. 2016. Implications of Fine-Grained Habitat Fragmentation and Road Mortality for Jaguar Conservation in the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. PLoS ONE 11:1-17. Links

- Cunha, H. F., F. G. A. Moreira, and S. S. Silva. 2010. Roadkill of wild vertebrates along the GO-060 road between Goiânia and Iporá, Goiás State, Brazil. Acta Cientiarum Biological Sciences 32:257-263. Links

- Deichmann, U., F. Marianne, J. Koo, and S. V. Lall. 2004. Economic structure, productivity, and infrastructure quality in southern Mexico. The Annals of Regional Science 38:361-385. Links

- Drews, C.. 1995. Road kill of animals by public traffic in Mikumi National Park, Tanzania with notes on baboon mortality. African Journal of Ecology 33:89-100. Links

- Ferreras, P., J. J. Aldama, J. F. Beltran, and M. Delibes. 1992. Rates and causes of mortality in a fragmented population of Iberian Lynx Felis pardina Temminck, 1824. Biological Conservation 61:192-202. Links

- Ford, A. T., A. P. Clevenger, and K. Rettie. 2010. The Banff wildlife crossings project: An international public-private partnership. Pp. 157-172 in Safe passages (Beckmann, J. P., A. P. Clevenger, M. Huijser, and J. A. Hilty, eds.). Island Press. Washington, U. S. A. Links

- Forman, R. T. T., D. Sperling et al. 2003. Road Ecology Science and Solutions. Island Press. U. S. A. Links

- Giordano, A. J.. 2015. Ecology and status of the jaguarondi Puma yagouaroundi: a synthesis of existing knowledge. Mammal Review 46:30-43. Links

- Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. 2014. Programa Nacional de Infraestructura 2014-2018. http://presidencia.gob.mx/pni/ accessed 01 march 2017. Links

- González Gallina, A., and G. Benítez Badillo. 2013. Road ecology studies for México: a review. Oecología Australis Special issue on Road Ecology 17:175-190. Links

- González-Gallina, A., G. Benítez-Badillo, O. R. Rojas-Soto, and M. G. Hidalgo-Mihart. 2013. The small, the forgotten and the dead: highway impact on vertebrates and its implications for mitigation strategies. Biodiversity and Conservation. 22:325-342. Links

- Grilo, C., D. J. Smith, and N. Klar. 2015. Carnivores: Struggling for survival in roaded landscapes. Pp. 300-312 in Handbook on Road Ecology (Van der Ree, R., D. J. Smith, and C. Grilo, eds.). Wiley-Blackwell. West Sussex. UK. Links

- Grosselet, M., B. Villa-Bonilla, and G. Ruiz-Michael. 2008. Afectaciones a vertebrados por vehículos automotores en 1.2 km de carretera en el Istmo de Tehuantepec in Proceedings of the Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. Links

- Gruisen, J. V.. 1998a. Rajasthan. Tiger Link 4:10-11. Links

- Gruisen, J. V.. 1998b. Uttar Pradesh. Tiger Link 4:14. Links

- Hall, E. R.. 1981. The mammals of North America. Segunda edición, John Wiley & Sons, New York. USA. Links

- Hegel, C. G. Z., G. C. Consalter, and N. Zanella. 2012. Mamíferos silvestres atropelados na rodovia RS-135, norte do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Biotemas 25:165-170. Links

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2015. Anuario estadístico y geográfico por entidad federativa 2015. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Aguascalientes, México. Links

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2016. Encuesta Nacional sobre Disponibilidad y Uso de Tecnologías de la Información en los Hogares 2016. Disponibilidad y Uso de Tecnologías de la Información en los Hogares 2016. http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/proyectos/enchogares/regulares/dutih/2016/ accessed 23 august 2017. Links

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2017. Estimación de cifras con base a las ventas reportadas por la Encuesta Mensual de la Industria Manufacturera (EMIM) y la AMIA, A.C. http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/registros/economicas/vehiculos/ accessed 02 february 2017. Links

- Jansen, D., K. Sherwood, and E. Fleming. 2010. The I-75 Project: Lessons from the Florida Panther. 205-221 in Safe Passages: highways, wildlife and habitat connectivity (Beckmann, J. P., et al. Eds.). Island Press. Washington, U. S. A. Links

- Kerley, L., J. M. Goodrich, D. G. Miquelle, E. N. Smirnow, H. B. Quigley, and M. G. Hornocker. 2002. Effects of roads and human disturbance on Amur tigers. Conservation Biology 16:1-12. Links

- Lorenzo, C., E. Espinoza, M. Briones, and F. A. Cervantes (eds.). 2006. Colecciones mastozoológicas de México. Instituto de Biología UNAM, Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología. México DF. Links

- Macdonald, D. W., A. J. Loveridge, and A. Rabinowitz. 2010a. Felid futures: crossing disciplines, borders and generations. Pp. 599-649, in Biology and conservation of wild felids (Macdonald, D. W., and A. J. Loveridge eds.). Oxford Univeristy Press. Oxford, UK. Links

- Macdonald, D. W., A. Mosser, and J. L. Gittleman. 2010b. Felid society. Pp. 125-160 en Biology and conservation of wild felids (Macdonald, D. W., and A. J. Loveridge eds.). Oxford Univeristy Press. Oxford, UK. Links

- Maehr, D. S., E. D. Land, and J. C Roof. 1991. Social ecology of Florida panthers. National Geographic Research and Exploration 7:414-431. Links

- McGuire, T.. 2012. No ordinary highway: A thirty-year retrospective, Trans-Canada Highway, Banff National Park of Canada. Pp. 197-201, in Rethinking protected areas in a changing world: Proceedings of the 2011 George Wright Society Conference on Parks, Protected Areas, and Cultural Sites (Weber, S. ed.). The George Wright Society, Hancock, Michigan, USA. Links

- Meraz, J., B. Lobato-Yáñez, and B. González-Bravo. 2010. El Ocelote (Leopardus pardalis) y Tigrillo (Leopardus wiedii) en la costa de Oaxaca. Ciencia y Mar XIV 41:53-55. Links

- Morales-Mávil, J. E., J. T. Villa-Cañedo, S. Aguilar-Rodríguez, and L. Barragán-Morales. 1997. Mortalidad de vertebrados silvestres en una carretera asfaltada de la región de Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, México. Ciencia y el Hombre-UV 27:7-23. Links

- Morrone, J. J., and J. Márquez. 2003. Aproximación a un Atlas Biogeográfico Mexicano: Componentes bióticos principales y provincias biogeográficas. Pp. 217-220 in: Una perspectiva latinoamericana de la biogeografía (J. J. Morrone, and J. Llorente Bousquets, eds.). Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. México. Links

- Ngopraset, D., A. J. Lynam, and G. A. Gale. 2007. Human disturbance affects habitat use and behavior of Asiatic leopard Panthera pardus in Kaeng Krachan National Park, Thailand. Oryx 41:343-351. Links

- Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. 2010. Protección ambiental-Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres-Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio-Lista de especies en riesgo. 2010. Diario Oficial de la Federación. Segunda Sección. México. Links

- Olson, D. D., J. A. Bissonette, P. C. Cramer, A. D. Green, S. T. Davis, P. J. Jackson, and D. C. Coster. 2014. Monitoring Wildlife-Vehicle Collisions in the Information Age: How Smartphones Can Improve Data Collection. PLoS One 9:e98613. Links

- Ortega-Huerta, M., and K. Medley. 1999. Landscape analysis of jaguar (Panthera onca) habitat using sighting records in the Sierra de Tamaulipas, Mexico. Environmental Conservation 26:257-269. Links

- Pacheco-Figueroa, C. J., R. C. Luna-Ruíz, E. J. Gordillo-Chávez, J. D. Valdez-Leal, E. Marcelo-Guadarrama, E. Moguel-Ordoñez, J. Saenz, E.E. Mata-Zayas, S. Arriaga-Weiss, L. J. Rangel-Ruíz, and L. M. Gama-Campillo. 2013. Mortalidad de fauna en carreteras de la zona costera tabasqueña. Pp. 205-209 in Perspectiva Científica desde la UJAT / 1ª. Ed. (Contreras-Sánchez, W. M. et al., eds.) Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco. Tabasco, México. Links

- Pallares, E., C. Manterola, D. A. Conde, and F. Colchero. 2015. Case study: Roads and Jaguars in the Mayan Forests. Pp. 313-316 in Handbook on Road Ecology (R. Van der Ree, D. J. Smith, and C. Grilo, eds.). Wiley-Blackwell. West Sussex, UK. Links

- Patterson, B. D., G. Ceballos, W. Sechrest, M. F. Tognelli, T. Brooks, L. Luna, P. Ortega, I. Salazar, and B. E. Young. 2007. Digital Distribution Maps of the Mammals of the Western Hemisphere, version 3.0. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia, USA. Links

- Peña-Mondragón, J. L.. 2004. Distribución de jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi cacomitli, Lacepede 1809) en el estado de Nuevo León, México. Tesis de Licenciatura. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Monterrey, Nuevo León, México. Links

- Prevosti, F. J, Turazzini G. F, and M. A. Chemusquy. 2010. Morfología craneana en tigres dientes de sable: alometría, función y filogenia. Ameghiniana 47:239-256. http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0002-70142010000200008&lng=es&tlng=es . accessed 26 september 2017. Links

- Ramírez-Pulido, J., N. González-Ruíz, A. L. Gardner, and J. Arroyo-Cabrales. 2014. List of recent land mammals of Mexico. Special Publications Museum of Texas Tech University 63:1-69. Links

- Reddy, S., and L.M. Dávalos. 2003. Geographical sampling bias and its implications for conservation priorities in Africa. Journal of Biogeography 30:1719-1727. Links

- Ritwinski, T., and L. Fahrig. 2015. The impacts of roads and traffic on terrestrial animal populations. Pp. 237-246 in Handbook on Road Ecology (R. Van der Ree, D. J. Smith, and C. Grilo eds.). Wiley-Blackwell. West Sussex. UK. Links

- Saeki, M., and D. W. Macdonald. 2004. The effects of traffic on the raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides viverrinus) and other mammals in Japan. Biological Conservation, 118:559-571. Links

- Sarda-Palomera, F., G. Bota, C. Vinolo, O. Pallares, V. Sazatornil, L. Brotons, S. Gomariz, and F. Sarda. 2012. Fine-scale birds monitoring from light unmanned aircraft systems. Ibis 154:177–183. Links

- Saunders, N. J.. 2005. El icono Felino en México: Fauces, garras y uñas. Arqueología Mexicana. 2005. Arqueología Mexicana. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. México 72:20-27. Links

- Secretaria de Comunicaciones y Transporte (SCT). 2016. Anuario estadístico Sector Comunicaciones y Transportes 2013-2018. Dirección General de Planeación. Dirección de Estadística y Cartografía (Coordinadores). Links

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). 2009. Programa de Acción para la Conservación de la Especie: Jaguar (Panthera onca). Dirección de Especies Prioritarias para la Conservación, Comisión Nacional de Áreas Protegidas. Ciudad de México, México. Links

- Shilling, F., S. Perkins, and W. Collinson. 2015. Wildlife/Roadkill observation and reporting systems. Pp. 492-501 in Handbook on Road Ecology (R. Van der Ree, D. J. Smith, and C. Grilo, eds.). Wiley-Blackwell. West Sussex. UK. Links

- Siegel, S., and N. J. Castellan. 1988. Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences (2a ed.) McGraw-Hill. New York, U. S. A. Links

- Simón, M. A., J.M. Gil-Sánchez, G. Ruiz, G. Garrote, E. B. McCain, L. Fernández, M. López-Parra, E. Rojas, R. Arenas-Rojas, T. del Rey, M. García- Tardío, and G. López. 2012. Reverse of the decline of the endangered Iberian lynx. Conservation Biology 26:731–736. Links

- Smith, D. J., and R. van der Ree. 2015. Field methods to evaluate the impacts of roads on wildlife. Pp. 82-95 in Handbook on Road Ecology (R. Van der Ree, D. J. Smith, and C. Grilo eds.). Wiley-Blackwell. West Sussex. UK. Links

- Srbek-Araujo, A. C., S. L. Medes, and A. G. Chiarello. 2015. Jaguar (Panthera onca Linnaeus, 1758) roadkill in Brazilian Atlantic Forest and implications for species conservation. Brazilian Journal of Biology 75:581-586. Links

- Stoner, K. J., A. R. Hardy, K. Fisher, and E. W. Sanderson. 2015. Conectividad entre Hábitats del Jaguar e Identificación de Lugares Potenciales de Mitigación de Impactos Carreteros en la Unidad de Recuperación Noroeste del Jaguar . Final report for the Wildlife Conservation Society to the U. S.Fish and Wildlife Service in response to F14PX00340. Links

- Taylor, S. K., C.D. Buergelt, M. E. Roelke-Parker, B. L. Homer, and D. S. Rotstein. 2002. Causes of mortality of free ranging Florida panthers. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 38:107-114. Links

- Vercayie, D., and M. Herremans. 2015. Citizen science and smartphones take roadkill monitoring to the next level. Nature Conservation 11:29-40. Links

Supplementary material 1

Records of road-killed felids in Mexico grouped by species. Each record includes the road or locality where the collision occurred, year of recording, name of the state, the source type of the record and origin of the record. Source types are: Mammal Collection (MC), scientific literature (SL), citizen science web page (CSW), report in government media (RGM), digital news (DN), non-governmental organization (NGO), personal communication (PC).

| Site | Year | State | Source type | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herpailurus yagouaroundi | |||||

| Escárcega | 1982 | Campeche | MC | DP | |

| Pablillo Galeana | 1989 | Nuevo León | SL | Peña-Mondragón (2004) | |

| Camino al Parque Funeral Guadalupe | 2003 | Nuevo León | SL | Peña-Mondragón (2004) | |

| Acapulco - Zihuatanejo 2.5km E de Zihuatanejo | 2007 | Guerrero | SL | Almazan-Catalan et al. (2013) | |

| México-Acapulco 3km NO Tierra Colorada | 2007 | Guerrero | SL | Almazan-Catalan et al. (2013) | |

| Valentín Gómez Farías | 2009 | Campeche | MC | VER-MAM IIB-UV1 | |

| Carretera Federal Escárcega-Chetumal Km 7 | 2010 | Campeche | MC | VER-MAM IIB-UV1 | |

| Arriaga- Ocozocoautla | 2010 | Chiapas | NGO |

|

|

| La Huerta-Melaque | 2010 | Jalisco | PC | Núñez R. | |

| Nueva Alemania cerca de puente Mal paso | 2013 | Chiapas | DN |

|

|

| Melaque-Tomatlán | 2013 | Jalisco | PC | Núñez R. | |

| La Ventosa | 2013 | Oaxaca | PC | Tepatlán-Vargas A. | |

| La Huacana-Lázaro Cárdenas | 2014 | Michoacán | PC | Núñez R. | |

| El Despoblado | 2015 | Estado de México | CSW | Conabio, Naturalista |

|

| Carretera La Ventosa | 2015 | Oaxaca | PC | McAndrews A. | |

| Tzimin | 2015 | Yucatán | PC | Zamora Bárcenas D. F. | |

| Carretera Jititol-Tuxtla Gutiérrez | 2016 | Chiapas | PC | Hidalgo Mihart M. | |

| Jolochero | 2016 | Tabasco | CSW | Conabio, Naturalista |

|

| Carretera Coatzacoalcos-Cárdenas | 2017 | Tabasco | DN |

|

|

| Parque Ecológico Chipinque A.C. | ? | Nuevo León | SL | Peña-Mondragón (2004) | |

| Rancho Lomas Bonito, Montemorelos | ? | Nuevo León | SL | Peña-Mondragón (2004) | |

| Leopardus pardalis | |||||

| Carretera 9, Rosario | 1989 | Sinaloa | SL | Brown y López-González (2001) | |

| Pochutla-Huatulco | 2003 | Oaxaca | SL | Meraz et al. (2010) | |

| Parque Ecológico Jaguarundi, La Cangrejera, Coatzacoalcos | 2011 | Veracruz | MC | CNMA1 | |

| Carretera Escarcega-Chetumal, Ejido Nuevo Conhuas | 2012 | Campeche | MC | CM-UAC1 | |

| El Roble | 2012 | Sinaloa | DN |

|

|

| Bacalar-Altos de Sevilla | 2013 | Quintana Roo | DN | SIPSE, Novedades de Quintana Roo |

|

| Calakmul | 2014 | Campeche | NGO |

|

|

| Calakmul, Ejido Constitución | 2014 | Campeche | MC | CM-UAC1 | |

| Puerto Vallarta-El Tuito (Conchas Chinas) | 2015 | Jalisco | NGO |

|

|

| San Juan-Tacuitapa | 2015 | Sinaloa | DN | El Debate, Mazatlán |

|

| Cozumel carretera costera | 2016 | Quintana Roo | DN | SIPSE, Novedades de Quintana Roo |

|

| Abratanchipa | 2016 | San Luis Potosi | CSW | Conabio, Naturalista |

|

| Carretera Federal 85 límites entre Linares y Montemorelos | 2016 | Nuevo León | PC | Ruiz Bautista M.G. | |

| Carretera Federal 85 Mpio. Villagrán | 2016 | Tamaulipas | CSW | Conabio, Naturalista |

|

| Carretera Federal 307, entre Puerto Morelos y Playa del Carmen | 2016 | Quintana Roo | PC | Castelazo Calva V. | |

| Carretera Tixméhuac | 2016 | Yucatán | DN |

|

|

| Tzucacab | 2016 | Yucatán | PC | Zamora Bárcenas D. F. | |

| Carretera Federal 207 entre Puerto Morelos y Playa del Carmen | 2017 | Quintana Roo | DN |

|

|

| Carretera Leona Vicario-Puerto Morelos | 2017 | Quintana Roo | PC | Castelazo Calva V. | |

| Carretera desconocida | 2017 | Campeche | MC | CM-UAC1 | |

| Leopardus wiedii | |||||

| Poblado de Lerma Mpio. Campeche | 2007 | Campeche | MC | CM-UAC1 | |

| Carretera a 5 Palos | 2013 | Veracruz | MC | VER-MAM IIB-UV1 | |

| Trapichillos | 2014 | Colima | RGM |

|

|

| Melaque-Tomatlán | 2014 | Jalisco | PC | Nuñez R. | |

| km 30 Autopista Campeche-Champotón, Villamadero | 2015 | Campeche | MC | CM-UAC1 | |

| Carretera Edzna-Campeche, Mpio. Campeche | 2015 | Campeche | MC | CM-UAC1 | |

| Avenida Universidad, Othon P. Blanco | 2015 | Quintana Roo | DN | Diario Respuesta |

|

| Carretera federal 74 | 2016 | Nayarit | CSW | Conabio, Naturalista |

|

| Chankana-Cozumel | 2016 | Quintana Roo | DN | Impctonoticias.mx |

|

| Xilitla | 2016 | Querétaro | DN | Opinión Pública |

|

| Carretera Federal Campeche-Mérida, Kobén | 200? | Campeche | MC | CM-UAC1 | |

| Lynx rufus | |||||

| 4.5 km S, 2.8 km E San Atenógenes | 1985 | Durango | MC | CRD1 | |

| 1 Km E Emilio Portes Gil Pue | 1990 | Puebla | PC | González Christen A. | |

| 12.2 km N, 20.0 km W Sombrerete | 1990 | Zacatecas | MC | CRD1 | |

| Vicente Guerrero | 1994 | Durango | MC | CRD1 | |

| El Centenario, 14.5 km W La Paz | 1997 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| El Centenario, 14.5 km W La Paz | 19992 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| El Centenario, 14.5 km W La Paz | 19992 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| El Comitán, 17.5 km W La Paz | 19992 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| El Comitán, 17.5 km W La Paz | 19992 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| 11 km NE Súchil | 1999 | Durango | MC | CRD1 | |

| 17.5 km N La Paz | 2000 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| El Comitán, 17.5 km W La Paz | 2000 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| El Centenario, 14.5 km W La Paz | 2000 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| Pátzcuaro-Uruapan | 2000 | Michoacán | PC | Nuñez R. | |

| km 53 carr. Durango-Canatlán, cerca J. Guadalupe Aguilera | 2003 | Durango | MC | CRD1 | |

| La Paz | 2004 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| km 37 carr. Durango-Mezquital | 2004 | Durango | MC | CRD1 | |

| El Triunfo | 2005 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| 6.8 km S, 1.3 km W La Zarca | 2005 | Durango | MC | CRD1 | |

| Santa Anita | 20092 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| Santa Anita | 20092 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| Balneario Acatita | 2009 | Durango | MC | CRD1 | |

| 3.73 km NE Villa Ocampo | 2009 | Durango | MC | CRD1 | |

| Huejuquilla-Tenzompa | 2009 | Jalisco | DN |

|

|

| Huejuquilla-Bolaños | 2009 | Jalisco | DN |

|

|

| 1.7 km S, 0.5 km W 5 de Mayo | 2010 | Durango | MC | CRD1 | |

| Ciudad Constitucion | 2011 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| 32 km S, 11 km W Santa Rosalia | 2012 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| Carretera Federal 7D El Sueco | 2013 | Chihuahua | PC | Hidalgo Mihart M. | |

| Límites Querétaro-Guanajuato | 2013 | Querétaro | PC | Zamora Bárcenas D. F. | |

| Carr. Guadalajara-Ameca, | 2014 | Jalisco | CSW | Conabio, Naturalista, Fauna Silvestre Atropellada |

|

| Carretera Federal 160 Pasando Entronque Jaltetelco-Oaxtepec | 2014 | Morelos | PC | González Gallina A. | |

| 13 km N Jesus Maria | 2015 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| 5 km S, La Paz | 2015 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| Carretera Federal 40 Durango-Gómez Palacio | 2015 | Durango | CSW | Conabio, Naturalista, Fauna Silvestre Atropellada |

|

| Carretera Federal 190 | 2015 | Oaxaca | CSW | Conabio, Naturalista, Fauna Silvestre Atropellada |

|

| Carretera Federal 45 Villa Insurgentes | 2015 | Zacatecas | CSW | Conabio, Naturalista, Fauna Silvestre Atropellada |

|

| La Paz | 2016 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| Los Planes | 2016 | Baja California Sur | MC | CIBNOR1 | |

| Nogales-La Escondida | 2016 | Sonora | CSW | Conabio, Naturalista, Fauna Silvestre Atropellada |

|

| Carretera Federal 2 Agua Prieta-Imuris | 20162 | Sonora | NGO | Sky Island Alliance | |

| Carretera Federal 2 Agua Prieta-Imuris | 20162 | Sonora | NGO | Sky Island Alliance | |

| Carretera Federal 2 Agua Prieta-Imuris | 20162 | Sonora | NGO | Sky Island Alliance | |

| Carretera Federal 2 Agua Prieta-Imuris | 20162 | Sonora | NGO | Sky Island Alliance | |

| Carretera Federal 2 Ciudad Juárez-Agua Prieta | 20162 | Sonora | NGO | Sky Island Alliance | |

| Carretera Federal 2 Ciudad Juárez-Agua Prieta | 20162 | Sonora | NGO | Sky Island Alliance | |

| Mazapil, Ejido Mahoma | 20162 | Zacatecas | PC | Martínez Hernández A. reportados por Ing. A.I. Rangel Galicia | |

| Mazapil, Ejido Mahoma | 20162 | Zacatecas | PC | Martínez Hernández A. reportados por Ing. A.I. Rangel Galicia | |

| Carretera Federal 15, Hermosillo-Tucson, km 92 | 20172 | Sonora | PC | Juan Carlos Bravo | |

| Carretera Federal 15, Hermosillo-Tucson, km 138 | 20172 | Sonora | PC | Juan Carlos Bravo | |

| Puma concolor | |||||

| Minatitlán-Manzanillo | 2013 | Jalisco | PC | Nuñez R. | |

| Durango-Gómez Palacio | 2013 | Durango | DN | AM Léon |

|

| Durango-Mazatlan | 2014 | Durango | RGM |

|

|

| Lagos de Moreno-San Luis | 2014 | Jalisco | DN | Zacatecas On line |

|

| Carretera Federal 2 Ciudad Juárez-Agua Prieta | 2015 | Sonora | PC | Bravo J.C. registro de Pérez-Cantú J.M. | |

| Panthera onca | |||||

| Melaque-Tomatlán | 2000 | Jalisco | PC | Nuñez R. | |

| Poblado de Cobá | 2014 | Quintana Roo | DN | SIPSE- Novedades de Quintana Roo |

|

| Cd. Mendoza-Córdoba | 2014 | Veracruz | DN | El Mundo de Orizaba |

|

| Sabancuy-Champotón | 2015 | Campeche | PC | Sánchez M. (CONANP Laguna de Términos) | |

| Sian Kaán Carretera 307 | 2015 | Quintana Roo | DN | El Universal, Union, Cancún Qroo. |

|

| Tulum-Playa del Carmen | 2015 | Quintana Roo | DN | Enfoque Radio |

|

| Tulum-Playa del Carmen | 2016 | Quintana Roo | DN | Reverso Revista |

|

| Escárcega-Xpujil | ? | Campeche | SL | Colchero et al. (2011) | |

-

Peña-Mondragón (2004)Distribución de jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi cacomitli, Lacepede 1809) en el estado de Nuevo León, México, 2004

-

Peña-Mondragón (2004)Distribución de jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi cacomitli, Lacepede 1809) en el estado de Nuevo León, México, 2004

-

Almazan-Catalan et al. (2013)Registros adicionales de felinos del estado de Guerrero, MéxicoRevista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 2013

-

Almazan-Catalan et al. (2013)Registros adicionales de felinos del estado de Guerrero, MéxicoRevista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 2013

-

Peña-Mondragón (2004)Distribución de jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi cacomitli, Lacepede 1809) en el estado de Nuevo León, México, 2004

-

Peña-Mondragón (2004)Distribución de jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi cacomitli, Lacepede 1809) en el estado de Nuevo León, México, 2004

-

Brown y López-González (2001)Tigres de la Frontera, 2001

-

Meraz et al. (2010)El Ocelote (Leopardus pardalis) y Tigrillo (Leopardus wiedii) en la costa de OaxacaCiencia y Mar, 2010

-

Colchero et al. (2011)Jaguars on the move: modeling movement to mitigate fragmentation from road expansion in the Mayan ForestAnimal Conservation, 2011