Introduction

Currently, the world continues to face a series of environmental challenges, among them, the resurgence of forest fires, long-lasting crises due to climate change, loss of biodiversity as well as ongoing problems related to environmental pollution (PNUMA, 2022). Latin America and the Caribbean have a wide marine and terrestrial biological diversity that is threatened by environmental degradation events, mostly anthropogenic, which generate a constant loss of biodiversity (WWF, 2020). In Mexico, a megadiverse country, there are environmental problems related to the heterogeneous national distribution of the hydraulic resources, an unbalanced expansion of urban areas, and, diverse anthropogenic activities, which have serious impacts on biodiversity conservation, including soil, air, and water pollution, as well as inadequate management and disposal of urban solid waste (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, 2021). Additionally, the environmental impact on public and ecological health caused by the COVID-19 pandemic should be added. While this impact includes some temporary positive aspects such as an improvement in air quality, ecological restoration of tourist sites, and a decrease in noise pollution, other negative effects have the potential to become environmental problems that worsen the current ones. Among these are those related to a significant increase in waste related to personal protective equipment for the prevention and control of COVID-19 (masks, gloves, etc.) and an increase in hazardous sanitary waste (Somani et al., 2020; Rume & Didar-UI Islam, 2020) that constitute a health and environment threats. Due to health measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, the increase in online purchases originating during periods of confinement has been reflected in an increase in home service packaging waste and a decrease in recycling activities (Somani et al., 2020; Zambrano-Monserrate, Ruanob, & Sanchez-Alcalde, 2020). It should also be noted that some previous environmental factors also increase the risk of aggravation of COVID-19. Thus, in Mexico, it has been documented that chronic exposure to air pollutants is associated with a higher mortality rate due to COVID-19 (Cabrera-Cano et al., 2021).

To prevent and solve environmental problems, research in the behavioral sciences field has exposed the need to deepen the background on person-environment transactions that are beneficial for the promotion of environmental sustainability (Djuwita & Benyamin, 2022). This type of research is of relevance when generating educational interventions aimed at the establishment of favorable behaviors toward the environment (Ajaps & McLellan, 2015). in this sense, some international references have sought to generate political consensus to preserve and improve the environment. An example of this was the first declarations of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm, Sweden (United Nations, 1973). This conference established the need to promote environmental education as part of the actions that could educate citizens in an integral and self-sustainable manner (Saldaña-Almazán, et al., 2020). Currently, the global framework for addressing various environmental issues is the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This agenda, formulated in 2015 by the United Nations, postulates 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aimed at ending poverty, protecting the environment, and improving life quality. Among the environmental dimensions, it is highlighted goals aimed at achieving universal and equitable access to safe drinking water, efficient use of affordable and non-polluting energy, creation of sustainable and environmentally friendly cities, responsible consumption, adaptation and awareness of climate change, protection of marine and coastal ecosystems and terrestrial life (United Nations, 2019). In these objectives, there are three axes of action namely: global (leadership among countries), local (mobilization of policies and governmental regulatory frameworks), and the axis of people (civil society, academia, etc.). To generate the solution to these objectives there are a series of prerequisites to comply, which must consider individual and organizational behaviors modification (Dobson, 2007; Do Paço & Laurett, 2018).

Within Mexican education, pro-environmental values and behaviors are promoted through the incorporation of environmental topics in curricula from elementary to higher education (Díaz, et al., 2021), however, such topics have not always proven to have a real impact on students (Álvarez & Vega, 2009). To educate toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), people-centered, action-oriented, and transformative approaches represent the most efficient way to train students for pro-environmental behavior in their daily actions (Saldaña-Almazán, et al., 2020). A direct alternative to promoting pro-environmental behavior within the educational setting involves modeling such behavior by authority figures who are respected and admired, such as parents and teachers (Djuwita & Benyamin, 2022; Jia & Yu, 2021; Uçar & Canpolat, 2019).

The psychological effects of COVID-19 quarantine have turned out to be a trigger for the greatest scenario crisis in the world, beyond the physical health of the population. The conditions of mobility restriction and home confinement due to COVID-19 have represented a series of demands and changes in lifestyles where the need to promote and adopt environmentally friendly behaviors that contribute to planetary sustainability is evident. In the pandemic context, such actions may well be instituted within the confining environments, as is the case in housing settings and nearby neighborhoods (Ramkissoon, 2020). Examples of such behaviors involve self-care activities, such as frequent hand washing, responsible use of water and electricity in the home, recycling, gardening, and conservation of green areas (Curtis, Smith, & Jungbluth, 2013). For conservation actions, it is essential to create educational programs whose technological mediation effectively facilitates the transmission of information and communication (Xiao, Liu & Ting, 2022). In Mexico, as in many countries worldwide, some of the educational changes had to use online education, which, in the case of teachers with pro-environmental behaviors (e.g. in favor of the environment) and leadership, is useful to raise awareness and lead students to develop behaviors that are more supportive of nature (Kesenheimer & Greitemeyer, 2021).

The study of behavioral expectations within the educational environment dates back to the research of Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) with the "Pygmalion Effect" phenomenon. In this phenomenon, the expectations that others have about a person's performance are considered to affect his or her effective performance, abilities, behaviors, etc. Some studies on organizational (Kierein & Gold, 2000), social (e.g. leadership; Eden, 1992), and educational (Szumski, & Karwowski, 2019), are consistent in pointing out that people who have positive expectations towards others (e.g. at school, workplace, family) produce positive relationships, attitudes, and behaviors.

In the present study, the concept of pro-environmental behavior is used as a synonym for environmentally protective behavior, pro-ecological behavior, environmentally responsible behavior, environmentally friendly behavior, and ecological behavior (Martínez-Soto, 2004). In general, pro-environmental behavior is understood as the set of intentional, directed, and effective actions that respond to social and individual requirements resulting from environmental protection (Corral-Verdugo, 2001). Operationally, this type of behavior can be evaluated to the aggregation of behaviors carried out by individuals in different spheres, for which there are scales of general ecological behaviors (Kaiser, et al., 1999).

It has been identified that although universities maintain a genuine concern for the greening of the College Curriculum and its effects on daily university life (Saldaña-Almazán, et al., 2020), little is known about the role of teaching expectations in the promotion of pro-environmental behaviors of college students. Concerning this type of population, some research indicates that young people are more receptive to generating greater pro-environmental behaviors and can be easily modeled by proven leadership figures (Whitburn, et al., 2020; Shrum, et al., 2021; Suárez-Perales, et al., 2021; Vanegas-Rico, et al., 2018).

The present research is useful for implementing emerging environmental policies from the field of education and psychology focused on the promotion of environmental sustainability in educational environments and its effects on society (Collado, et al., 2021; Saldaña-Almazal, et al., 2020). In line with this, it is important to highlight reports on the effectiveness of the establishment of environmental psychology courses as a means to educate on several environmental issues and their impact on the pro-environmental behaviors induction (Rossi, 2018; Zhao, et al., 2021).

Under the above, this study aimed to know the influence of the expectations of teaching pro-environmental behavior on the acquisition of pro-environmental behaviors (general ecological behaviors) of a group of college students who took an online environmental psychology course during the COVID-19 contingency.

Material and Methods

This research had a quantitative, trans-sectional design of correlational scope.

A sample of 33 students was obtained through a non-probabilistic purposive sampling considering a population of 54 students of an environmental psychology course. The inclusion criterion was that they were college students who had taken the course in the second term of 2020 (August). The mean age of the participants was 21.69 years with a standard deviation of 1.70 (age range 10-24 years). Of the total sample, 19 participants were female (57.6 % of the sample) and the remaining were male (n= 14; 42.4 %).

An abbreviated version of the General Ecological Behaviors scale (Kaiser, 1998) was used to evaluate the pro-environmental behavior of the participants. The initial adaptation to the Mexican context was developed by Corral-Verdugo et al. (2009) obtaining adequate internal consistency values (Cronbach's alpha = 0.78). In the present study, a recent and reduced version of this scale reported by Venegas-Rico, et al. (2014) was used, which has 7 items and a four-point Likert-type response format (1 = Never to 4 = Always). To know the expectation of pro-environmental behavior of others (the probability that others are behaving pro-environmentally, in this case, the faculty of the environmental psychology course), the Scale Expectation of Environmental Behavior of Others (Vanegas, et al., 2018) was used. The instrument used evaluates 8 items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.78) and a 5-point Likert-type response format (1 = Not at all likely to 5 = Very likely) to account for the perceived likelihood of the teacher acting pro-environmentally (4 items; Cronbach's alpha = 0.77) for example "They care about taking care of the water" and against the environment (4 items; Cronbach's alpha = 0.79) for example "Throwing garbage in wrong places".

The environmental psychology course lasted 125 hours in online mode and pursued the following objectives: a) To know what environmental psychology is, b) To identify the basic processes of perception and cognition of the environment and the factors that impact them, c) To know how the environment impacts on the individual and his relationship with others, d) To acquire theoretical and practical skills to promote pro-environmental behavior, and e) To identify the main areas of intervention of Environmental Psychology.

Two groups of college students who had taken this course were invited to answer the instruments, explaining that this was an environmental psychology study. They were assured that their participation would be anonymous, voluntary, and with prior consent obtained through their approval in an electronic form. After approval to participate, the approximate response time for filling out the questionnaire was 7 minutes.

In the data analyses, descriptive statistics were used for the graphical and tabular representation of the variables, as well as the evaluation of averages and dispersion measures. The normality of the distribution of the values was analyzed through the Shapiro Wilks test and by obtaining the values of skewness and kurtosis. Both elements demonstrated the absence of the normality assumption both in the variables of environmental self-behavior and in the expectation of the teacher's pro-environmental behavior, so it was decided to use Spearman's rho test to analyze the correlation between the variables. Statistical analyses were performed with JASP 0.14.1.0 software.

Results and Discussion

Initially, means and standard deviations were calculated for environmental self-behavior and the expectation of the teacher's pro-environmental behavior. About the first variable, a high score was obtained (M= 3.91, SD= 0.51), considering that the values could range from 1 to 5. High values reflect a higher general pro-environmental behavior among the participants. On the other hand, the expectation of the teacher's pro-environmental behavior obtained an intermediate (slightly high) level (M= 3.57, SD= 0.45), given that the score is closer to the theoretical mean of the instrument (M=3). Table 1 shows the rest of the descriptive statistics for both variables.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics for environmental self-behavior and expectation of the teacher's pro-environmental behavior.

| Environmental self-behavior | The expectation of teacher’s pro-environmental behavior | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 3.91 | 3.57 |

| Median | 4.00 | 3.71 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.510 | 0.454 |

| Minimum | 2.50 | 2.43 |

| Maximum | 4.63 | 4.29 |

| Skewness | -1.21 | -1.33 |

| Kurtosis | 1.64 | 1.45 |

| Shapiro-Wilk (W) | 0.894 | 0.850 |

| Shapiro-Wilk (p) | 0.004 | < .001 |

| 25th percentile | 3.75 | 3.43 |

| 50th percentile | 4.00 | 3.71 |

| 75th percentile | 4.25 | 3.86 |

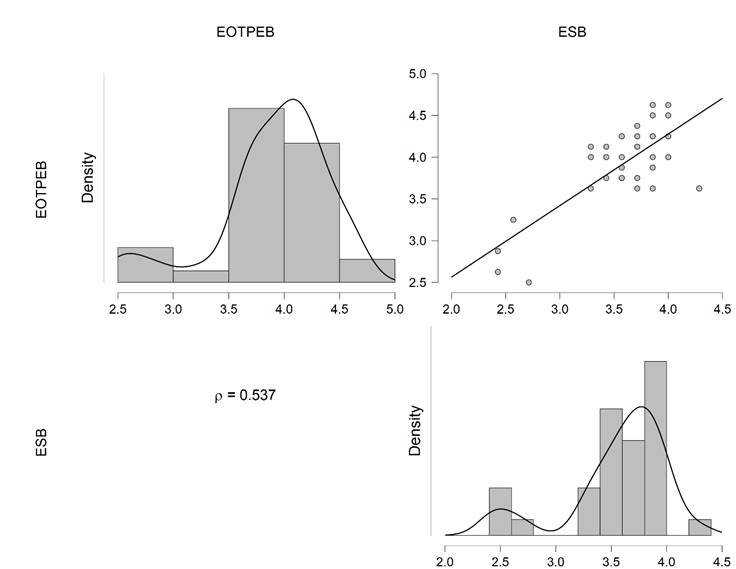

The correlation between the two variables was then analyzed. Figure 1 shows the correlation points and distribution parameters of the variables related to the self-perception of pro-environmental behavior and the expectation of teachers’ pro-environmental behavior. In Figure 1, the points obtained in the scatter diagram reflect the existence of a moderate, positive, and significant association between the perceived pro-environmental behaviors of the college teacher and the pro-student environmental self-behaviors (p <.001, rs= 0.54). That is higher perceived expectations of the teacher's pro-environmental performance positively influence students' self-evaluation of their overall environmental self-behavior. Thus, the importance of actively modeled social influences can be evidenced (Vanegas, et al., 2018) through the teaching of a course with environmental contents, which is congruent with the notion that the pro-environmental acting of others can be a guide to directly channel pro-environmental self-behaviors (Corral-Verdugo, 2001). The findings highlight social expectations as social norms that can be predictors of pro-environmental behaviors (Carrus, et al., 2010).

Note. EOTPEB = Expectation of teacher’s pro-environmental behavior; ESB = environmental self-behavior

Figure 1 Correlation between environmental self-behavior and expectation of the teacher's pro-environmental behavior.

Results also denote a greater sensitivity of college students to perform this type of behavior (Doherty & Clayton, 2011), which is relevant if we ponder that this population may play an important role in environmental decision-making in their professional and public life (Díaz, et al., 2020).

Unlike other studies where the expectations of the ecological behavior of other actors are analyzed, for example, family and friends (Collado, et al., 2017; Casaló & Escario, 2016), the present work was able to document the role of the expectations of the teacher's pro-environmental behavior in the establishment and socialization of environmental behaviors in young college students. Research on the expectations of teachers' pro-environmental behavior has little support in the psychoenvironmental literature. This is in addition to previous literature regarding the effect of others' behavioral expectations on their attitudes and behaviors in diverse contexts (Kierein & Gold, 2000; Eden, 1992; Szumski, & Karwowski, 2019).

While it is assumed that teacher expectation of pro-environmental behavior is positively associated with pro-environmental behavior in college, other contextual, situational, and predisposition factors must be taken into consideration to model these behaviors (Sahin, et al., 2021). Hence, future studies could probe levels of involvement, behavioral change, and temporal effects in other areas of pro-environmental acting (Elf, et al., 2019; Lange & Dewitte, 2019; Shafiei & Maleksaeidi, 2020).

One study limitation is the number of college students. Given that this could in part limit the generalizability of the study's findings, it is proposed that future research should consider not only larger samples, but also samples from different courses and semesters within the same context.

Likewise, the replication of this type of findings should be considered in other contexts of technical and methodological approaches (e.g., experimental research) where the measurement and intervention aspects can be replicable (Shadish, et al., 2002).

Conclusions

As reported by several authors (Sachdeva, et al., 2021; Daryanto, et al., 2022; Alla, et al., 2020), the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a series of collateral effects that require immediate interventions involving active changes in lifestyles and attitudes in favor of environmental conservation as a means to promote resilience of cities to various public as well as ecological health crises (Ramkissoon, 2020). With the present research, it is reaffirmed that research on environment and human behavior offers a theoretical, empirical, and methodological potential useful to promote low-cost and impactful evaluations and interventions in favor of promoting a culture of sustainability (Martínez-Soto, 2017). Obtained data are in line with the goals compliance of SDGs: 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities, 12 Responsible Production and Consumption, and 13 Climate Action (United Nations, 2020; UN, 2022). It can be stated that the generation of pro-environmental behaviors as a prerequisite for the full compliance with the SDGs (Dobson, 2007) represents a commitment of educational centers to respond to the requirements of the promotion of sustainability in the spheres of global and local action and the different actors of society. A sustainable university is one that actively acts on the knowledge of the university community to address and face all the present and future ecological conditions and social problems (Martínez-Soto, 2017; Sandoval-Escobar, et al., 2019). Therefore, the findings found highlight the role of universities as those that together with society play an important role in the prevention, promotion, and solution of environmental problems in crisis periods.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)