Introduction

Drying is defined as the process of removing moisture by the transfer of heat and mass simultaneously (Janjai & Bala 2012; El-Sebaii & Shalaby, 2012). This method is common in food preservation (Ertekin & Yaldiz, 2004). The drying process is divided into two stages. The first occurs on the surface of the material at a constant drying rate, and is similar to the evaporation of water in the environment. The second is carried out at a decreasing drying rate. The condition of the second stage is determined by the properties of the material being dried (Can, 2000; El-Sebaii & Shalaby, 2012).

Sun-drying is the oldest method used to preserve agricultural products such as grains, fruits and vegetables (Belessiotis & Delyannis, 2011). However, this type of drying under hostile climatic conditions leads to severe losses in the quantity and quality of the product (Pangavhane, Sawheny, & Sarsavadia, 2002). These losses are related to contamination by dirt and dust, and infestation by insects, rodents and other animals (Janjai & Bala 2012; Prakash, Laguri, Pandey, Kumar, & Kumar, 2016). For this reason, the introduction of solar drying technology in developing countries can reduce postharvest losses and significantly improve product quality compared to traditional methods such as shade-drying or direct sun-drying (Yaldiz, Ertekin, & Uzun, 2001).

One of the solar drying systems with the greatest potential is the greenhouse type (SSSTI), since it can be used on an industrial scale due to its processing capacity. Usually, its structure is made of galvanized iron bars, and the roof and walls are made of polycarbonate. The front wall has air inlets. A thin layer of products is placed on trays located on single-level raised platforms to facilitate loading and unloading. Solar radiation passing through the roof heats the air, the products and the concrete floor. Hot air passes through and over the product absorbing its moisture. Damp air is usually removed from the dryer by extractors. A special greenhouse solar dryer design is one that has a parabolic shape and is ventilated with extractors powered by a photovoltaic solar energy system (Janjai et al., 2009).

Bala (1997) was one of the pioneers in studying the fundamentals of the heat and mass transfer process of the greenhouse solar dryer. Other researchers have reported results related to heat and mass transfer in tunnel-type greenhouse solar dryers (Hossain, Woods, & Bala, 2005). Recently, mathematical models of improved versions of greenhouse solar dryers (Janjai et al., 2009) and dryers that use photovoltaic solar energy to efficiently control ventilation have been proposed (Barnwal & Tieari, 2008; Janjai et al., 2009).

Every drying system must be designed in an appropriate way to meet the requirements of a specific product and present its optimum performance in terms of drying times and final product quality. This means that the characteristics (dimensions, roof and structural materials, microclimate, among others) of the dryer depend on environmental and economic factors. However, large-scale experiments with different products, seasons of the year and system configurations can be very costly and impractical (Bala & Woods, 1994). Therefore, the development of mathematical models (static and dynamic) and computer simulations is a basic tool to predict the behavior of a solar drying system.

The development of mathematical models of solar dryers is necessary in order to know the physical processes associated with dehydration, and to control, design and optimize this system. In addition to contributing to the design of dryers, mathematical models are important in the operation of the system, the quality of the product to be dried and energy savings (Prakash et al., 2016). In a recent review article (Chauhan, Kumar, & Gupta, 2016) on SSSTI thermal models, the importance of using this type of mechanistic model in the design and control of these systems is emphasized.

A mathematical model is a simplified representation of a system. In general, three approaches have been applied to mathematically model the solar dryer: mechanistic models, empirical models and numerical or computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models. According to Bala and Janjai (2013), the future of research on solar dryers is aimed at the study of the optimization of product quality and design parameters through the use of techniques such as CFD.

The aim of this study is to provide an overview of the different approaches to modeling and simulating greenhouse solar dryers, both of natural and forced convection, and present the models used to design, optimize and control the environment of this system. The task is addressed by taking into account the most general classification of greenhouse solar dryers, which is the division between natural (passive) and forced (active) convection solar dryers.

Classification of solar dryers

One way to classify solar dryers in a general way is according to the mechanism by which the energy used to remove the moisture is transferred to the product (Prakash & Kumar, 2013; Prakash & Kumar, 2014c). In this way, three types can be identified: 1) direct solar dryer, 2) indirect solar dryer and 3) mixed-mode solar dryer. On the other hand, Fudholi, Sopian, Ruslan, Alghoul, and Sulaiman (2010) present a more precise classification, in which they take into account the design of the system components and the way in which the solar energy is used (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Classification of solar dryers for agricultural products (Adapted from Fudholi et al., 2010).

Greenhouse solar dryers

Vijayavenkataraman, Iniyan, and Goic (2012) define a greenhouse solar dryer as a large solar collector in which the dehydration process of a product (agricultural, marine or livestock) takes place. According to Prakash and Kumar (2014c), this type of dryer is included in the direct or mixed category, given the fact that in both categories there is an enclosure with a transparent cover; that is, there is absorption of solar radiation on the product. In addition, Kumar, Tiwari, Kumar, and Pandey (2006) state that these dryers can be subclassified according to their structure: 1) spherical dome, designed to take maximum advantage of global solar radiation, and 2) flat roof, which promotes a suitable mixing of the air inside the dryer.

A more general classification of this type of dryer includes only two categories: 1) passive greenhouse solar dryer (natural convection) and 2) active greenhouse solar dryer (forced convection, Bala & Debnath, 2012; Prakash & Kumar, 2013, Prakash & Kumar, 2014c). In the first case, the airflow is established by the fluid buoyancy forces generated from the temperature difference at different points in the fluid. In the second, the airflow is provided by a fan powered by electricity or fossil fuel.

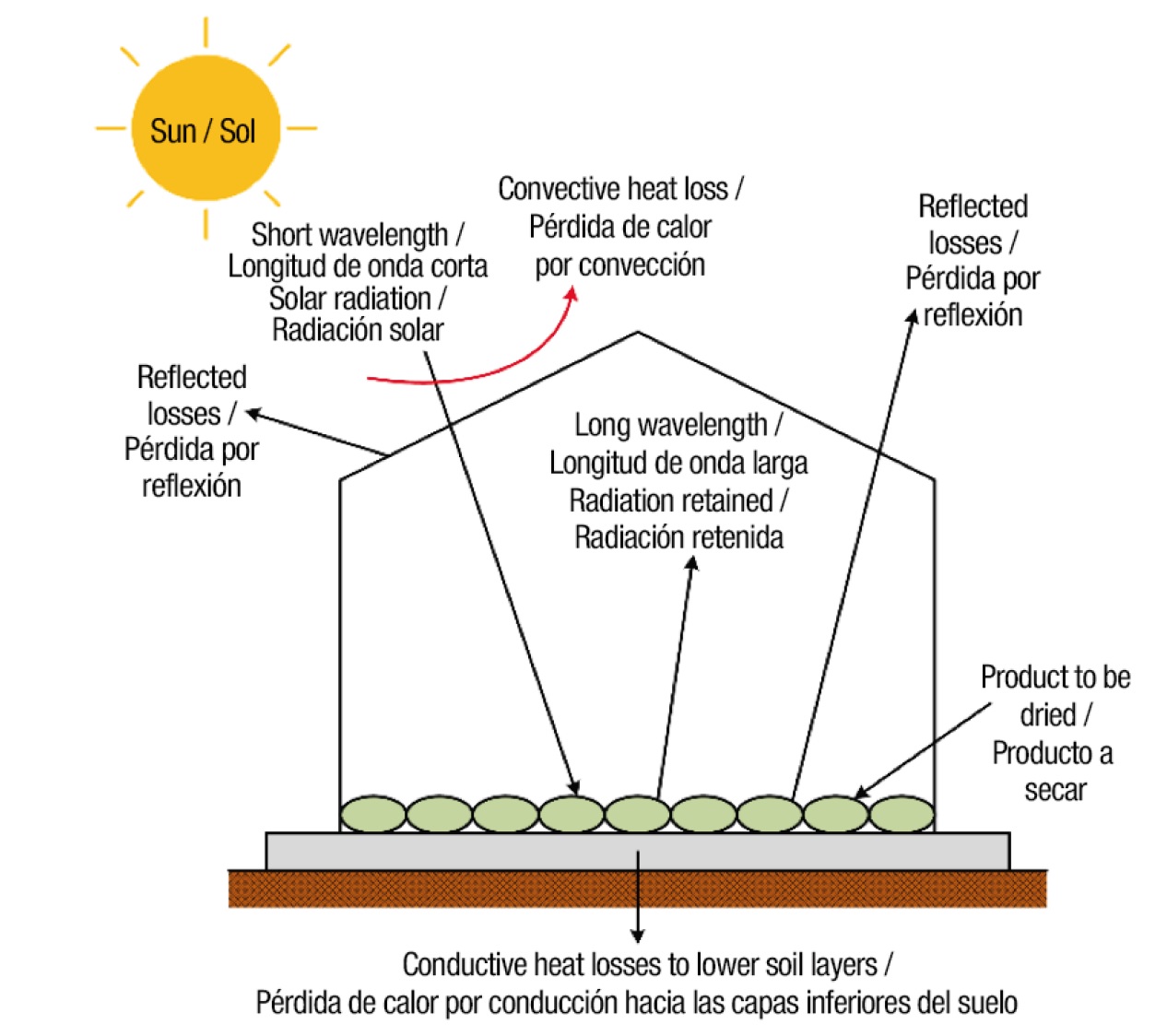

Figure 2 illustrates the operating principle of a greenhouse solar dryer. It shows that the product to be dried is placed on a layer to receive the solar radiation that is transmitted through a transparent cover, whereas the moisture is removed from the system by natural or forced convection (Sahdev, 2014). During the process, a fraction of the incident solar radiation on the cover is transmitted to the interior of the dryer, while another is reflected. Subsequently, a fraction of the transmitted radiation is reflected in short wavelength form from the product surface to the atmosphere through the cover. The remaining radiation is absorbed by the product, thereby increasing its temperature and resulting in long wavelength radiation, which does not escape into the external environment due to the presence of the transparent cover. This increases the temperature inside the system.

The transparent cover also fulfills the objective of reducing heat loss by direct convection to the environment, thus preventing the temperature in the interior from decreasing. The loss of heat or energy by convection and evaporation occurs inside the dryer, from the product to its surroundings. Finally, the moisture produced by the evaporation of water from the product is removed from the dryer by a chimney (natural convection) or a fan-induced airflow (forced convection, Kumar, Tiwari, Kumar, & Pandey, 2006).

Figure 2 Physical processes of radiation, convection and conduction that occur in a greenhouse solar dryer (Adapted from Sahdev, 2014).

Mathematical modeling of greenhouse solar dryers with natural convection

One of the main advantages of solar drying systems with natural convection over those with forced convection is that the former require relatively little economic investment due to their low operation and maintenance costs (Bala & Debnath, 2012). Therefore, in spite of having difficulties in terms of temperature control and a limited drying rate, these systems are a more viable option for domestic-scale use (Janjai & Bala, 2012). According to the literature, three types of models have been used to mathematically model greenhouse solar dryers with natural convection: mechanistic, empirical and numerical or CFD ones, the last-mentioned models in a very incipient way.

Mechanistic models, also called theoretical, are based on first principles, particularly in the mass and energy transfer processes that are carried out during drying and in the greenhouse-dryer environment. It is possible to obtain a dynamic model represented by a set of ordinary (usually non-linear) differential equations, by means of instantaneous balances of energy and matter in a non-stationary state in the cover for the air inside the greenhouse, inside the product and on the dryer floor. Since the resulting model is not linear, the solutions are necessarily numerical. Some researchers have studied, with this type of model, the change in the air temperature with respect to time inside the dryer, the product, the ground and the cover, in addition to the change in the moisture content of the product during the dehydration process (Kumar & Tiwari, 2006a; Farhat, Kooli, Kerkeni, Maalej, Fadhel, & Belghith, 2004).

On the other hand, some papers report the convective heat transfer coefficient, which is an important parameter in the simulation of the drying rate, since the temperature difference between the air and the product varies with this coefficient (Anwar & Tiwari, 2001). This has been addressed in natural convection greenhouse solar dryers for khoa drying (Kumar, 2014) and under no-load conditions (Chauhan & Kumar, 2016).

Although drying kinetics can be described using transport properties together with those of the drying medium, a drying constant defined by the thin layer equation is used in agricultural products (Togrul & Pehlivan, 2004). There are numerous studies in which different models have been generated. In the specific case of passive greenhouse solar dryers, thin layer models have been used to study the drying kinetics of amaranth (Ronoh, Kanali, Mailutha, & Shitanda, 2010), coconut (Arun & Sreenarayanan, 2014), red pepper (Fadhel, Kooli, Farhat, & Belghith, 2014) and tomato (Sacilik, Keskin, & Elicin, 2006; Demir & Sacilik, 2010).

To date, fuzzy logic-based models are little used to model the climate of solar dryers. Recently, researchers have begun to use neuro-fuzzy models (Prakash & Kumar, 2014a), which combine the advantages of fuzzy logic systems with artificial neural networks.

It is also possible to obtain spatial models represented by a set of differential equations in partial derivatives, for several variables of the system, carrying out integral balances of matter and energy. The resulting equations are generally non-linear and require numerical solutions. Like fuzzy logic, CFD is a technique that has only been used in an incipient way in the modeling of natural convection greenhouse solar dryers (Lokeswaran & Eswaramoorthy, 2013; Somsila & Teeboonma, 2014). According to Versteeg and Malalasekera (1995), the advantages of CFD analysis compared to experimentation-based ones can be summarized as: a substantial reduction in time and costs for the generation of new designs, the possibility of analyzing systems under conditions that are difficult to create experimentally, the ability to study systems under hazardous conditions, and, finally, the ability to assess a level of detail that is virtually unlimited. That is, experimental methods are more expensive the greater the number of measurement points, while CFD codes can generate a large volume of results at no additional cost, making parametric studies easier to do.

CFD comprises the Navier-Stokes equations, expressed as a set of partial differential equations. These equations can be represented as shown in Equation 1:

where, ∂ is the partial derivative, 𝜌 is the density (kg·m-3), t is the time, ∇ is the divergence, ∅ is any physical quantity modeled (e.g. air temperature and humidity, moisture content of the product to be dehydrated), 𝑢 is the wind speed (m·s-1), Г is the diffusion coefficient (m2·s-1) and 𝑆 is the source term.

Table 1 shows a summary of research on mathematical modeling of natural convection greenhouse solar dryers.

Table 1 Papers on mathematical modeling of natural convection greenhouse solar dryers.

| Work performed | Reference |

|---|---|

| Development and evaluation of a model that includes an ordinary differential equation to predict jaggery temperature. | Kumar and Tiwari (2006a) |

| Proposal for an ordinary differential equation to simulate moisture loss from pepper as a function of ventilation rate, air temperature, product temperature and solar radiation transmitted through the dryer cover. | Farhat et al. (2004) |

| Study of convective heat and mass transfer coefficients during drying of khoa as a function of size. | Kumar (2014) |

| Evaluation of the heat utilization factor, convective heat transfer coefficient and coefficient of diffusivity coefficient by thermal performance analysis for a north-wall insulated dryer under no-load conditions. | Chauhan and Kumar (2016) |

| Use of six thin layer models to study the drying process of amaranth grains. | Ronoh et al. (2010) |

| Testing of 10 thin layer mathematical models to describe the drying kinetics of coconut. | Arun and Sreenarayanan (2014) |

| Study of six thin layer models of the red pepper drying process under three different conditions. | Fadhel et al. (2014) |

| Use of 10 thin layer models to study the drying process of organic tomato in a tunnel-type solar dryer. | Sacilik et al. (2006) |

| Use and comparison of five thin layer models to determine the drying kinetics of tomato. | Demir and Sacilik (2010) |

| Development and evaluation of a neuro-fuzzy model to predict the temperature of jaggery and the dryer, plus evaporated moisture. | Prakash and Kumar (2014a) |

| Numerical analysis using CFD of a greenhouse solar dryer with no product to dehydrate inside. The dryer model was developed in GAMBIT and analyzed in FLUENT 6.3.26. | Lokeswaran and Eswaramoorthy (2013) |

| Study of the distribution of temperature and airflow inside a greenhouse solar dryer for rubber using CFD. | Somsila and Teeboonma (2014) |

Mathematical modeling of greenhouse solar dryers with forced convection

According to Bala and Janjai (2013), the success achieved by natural convection dryers has been limited due to the low rate of induced airflow. This has led researchers to concentrate their efforts on the development of forced convection solar dryers powered by electricity from the power grid, fossil fuels and mainly the use of photovoltaic (PF) panels. These dryers have some advantages over natural convection ones, such as: they are used on an industrial scale because of the large product load volume that can be dried and the microclimate variables can be controlled more precisely.

At present, one of the most widespread dryer models at research and commercial level is the PF-ventilated parabolic greenhouse solar dryer. This was developed at the Solar Energy Research Laboratory at the University of Silpakorn in Thailand (Bala & Janjai, 2013).

Unlike passive solar dryers, research work on active ones has been limited to the use of theoretical and empirical models, leaving aside the application of CFD, which still needs to be tested in this system.

Regarding forced convection greenhouse solar dryers, the temporal behavior of both the temperature and the moisture of the product has also been studied, thanks to the development of models based on mass and energy balances that finally concludes in a system of ordinary or partial differential equations. It is important to highlight that, for the development of the energy balance in a non-stationary state, the researchers make several assumptions that allow simplifying the system and processes modeled (Jain & Tiwari, 2004b; Kumar & Tiwari, 2006a; Janjai et al., 2009; Tiwari, Tripathi, & Tiwari, 2016):

The heat capacity of the dryer cover and structure is negligible.

A single layer of product to be dried is considered.

There is no stratification in dryer air temperature.

The absorptivity of air is negligible.

The fraction of solar radiation that is lost through the north wall is negligible.

The dynamic theoretical models proposed by different authors can be generically defined by a non-linear first order ordinary differential equation of the form:

where x Є R n , u Є R m , p Є R q and x 0 Є R n . The vector of the state variables (x) contains the variables that characterize the system, such as temperature (of the air, product and cover), moisture ratio inside the dryer and moisture content of the product to be dehydrated. The input vector (u) contains variables that express the effect of the environment on the behavior of the system, such as the temperature and humidity of the outside air, global solar radiation and ventilation rates. The vector (p) represents the thermodynamic parameters of the model, such as the conductive, convection and radiative heat transfer coefficients. In general, f is a non-linear vector function, so the dynamic model has no analytical solution and must be solved by numerical integration. As the state collects all system information in an instant, it is possible to define the relationship of the output variable (y) with the state and input. This general non-linear algebraic equation is denoted as:

Some output variables of the mathematical models of a solar dryer are the same states or a transformation of them, since this allows comparing them with the data measured by the sensors. Since the resulting systems of equations are highly non-linear, their solution is necessarily numerical. The most used method for the solution of the resulting system is that of finite differences (Janjai, Srisittipokakun, & Bala, 2008; Janjai et al. 2009; Janjai, Intawee, Kaewkiew, Sritus, & Khamvongsa, 2011; Janjai, 2012; Janjai, Phusampao, Nilnont, & Pankaew, 2014; Jitjack, Thepa, Sudaprasert, & Namprakai, 2016).

There is research that includes the development of models to simulate the drying process (Bekkioui, Hakam, Zoulalian, & Sesbou, 2011; Aghbashlo, Müller, Mobli, Madadlou, & Rafiee, 2015; Azaizia, Kooli, Elkhadraoui, Hamdi, & Guizani, 2017), the thermal performance of the dryer (Almuhanna, 2012; Tiwari et al., 2016) and the convective heat transfer coefficient obtained during the drying of onion (Kumar & Tiwari, 2007), grape (Barnwal & Tiwari, 2008) and papad (Kumar, 2013). It is even possible to find mechanistic mathematical models, which have been used in conjunction with economic models to find the optimum dimensions for a solar tunnel dryer for drying chilli (Hossain et al., 2005).

The thin layer models in forced convection greenhouse solar dryers have been used in tomato (Prakash & Kumar, 2014b). Unlike theoretical models, empirical ones allow summarizing data and relating the input and output variables of a system. Artificial neural networks are non-linear empirical or black-box models that have been used to describe and explain the behavior of the drying process of jackfruit bulbs (Bala, Ashraf, Uddin, & Janjai, 2005) and rubber sheets (Janjai, Piwsaoad, Nilnont, & Pankaew, 2015) in this type of dryer. Artificial neural networks require a large amount of data and a lot of training time for the user. Also, fuzzy logic has been applied to predict the evaporation rate in jaggery (Prakash, Kumar, Kaviti, & Kumar, 2015) and in neuro-fuzzy models to simulate the behavior of a greenhouse dryer under no-load conditions.

Table 2 shows a summary of the research relating to mathematical modeling of forced convection greenhouse solar dryers.

Table 2 Papers on mathematical modeling of forced convection greenhouse solar dryers.

| Work performed | Reference |

|---|---|

| Study of a dryer (with an integrated photovoltaic panel) through energy balances to predict the temperature of the panel and the air inside. In addition, use of an ordinary differential equation to predict the temperature of the product. | Tiwari et al. (2016) |

| Analysis of the performance of a dryer with a roof-integrated solar collector, using a model based on ordinary differential equations for the analysis of the collector and a system of partial differential equations for the analysis of the dryer. | Janjai et al. (2008) |

| Development of a system of partial differential equations to describe the heat and moisture transfer of peeled longan (Asian fruit belonging to the litchi family) and banana processed in a PF-ventilated solar dryer. | Janjai et al. (2009) |

| Development of a model based on a system of partial differential equations to describe the heat and moisture transfer in chilli, banana and coffee during drying. | Janjai et al. (2011) |

| Generation of a model with a system of partial differential equations to describe the heat and moisture transfer of osmotically dehydrated tomato. | Janjai (2012) |

| Development of a model using partial differential equations to describe the heat and moisture transfer of macadamia nuts during the drying process. | Janjai et al. (2014) |

| Testing and generation of a system of partial differential equations to predict the air temperature inside a dryer for rubber drying. | Jitjack et al. (2016) |

| Development and validation of a mathematical model based on ordinary differential equations to simulate the wood drying process. | Bekkioui et al. (2011) |

| Development of a model integrating an equilibrium drying model and thin-layer drying principles. The model was evaluated experimentally and TRNSYS was used to simulate the drying process of chamomile flowers. | Aghbashlo et al. (2015) |

| Generation of a mechanistic model for a greenhouse dryer with an attached solar collector to study the influence of the area of the product to be dried, airflow rate and collector area on the air temperature and humidity inside the dryer. | Azaizia et al. (2017) |

| Evaluation of the performance of a dryer by thermal balance derived in algebraic equations showing the distribution of incident solar energy in useful heat gain and thermal losses. | Almuhanna (2012) |

| Evaluation of the effect of drying batch size on convective heat transfer coefficient in onion flakes. | Kumar and Tiwari (2007) |

| Study of the convective heat transfer coefficient in grapes in a hybrid photovoltaic-thermal (PV/T) greenhouse dryer. | Barnwal and Tiwari (2008) |

| Determination of average convective and evaporative heat transfer coefficients during papad drying. | Kumar (2013) |

| Use of a model based on partial differential equations together with an economic (algebraic) model to find the optimum dimensions of a chilli dryer. | Hossain et al. (2005) |

| Testing of seven thin layer models to predict the drying process of tomato flakes. | Prakash and Kumar (2014b) |

| Use of the multilayer neural network method to predict the performance of a solar tunnel dryer for drying jackfruit bulbs. | Bala et al. (2005) |

| Development of a multilayer neural network model to predict the performance of a rubber sheet dryer. | Janjai et al. (2015) |

| Use of a fuzzy logic model to predict the rate of moisture evaporation from jaggery in a controlled environment. | Prakash et al. (2015) |

Modeling of greenhouse solar dryers with natural and forced convection

Some researchers have opted to develop complementary works, in which they have presented a thermal model for a dryer with both natural and forced convection (Table 3; Jain & Tiwari, 2004b). It should be noted that these studies have concentrated on the study of the convective heat (Jain & Tiwari, 2004a; Tiwari, Kumar, & Prakash, 2004) and mass (Kumar & Tiwari, 2006b; Kumar, Kasana, Kumar, & Prakash, 2011) transfer coefficient for different agricultural products.

Table 3 Work carried out on greenhouse solar dryers with natural and forced convection.

| Work performed | Reference |

|---|---|

| Development of theoretical models based on ordinary differential equations to study the thermal behavior of cabbage and peas during the drying process under the sun and inside a greenhouse (in natural and forced convection). | Jain and Tiwari (2004b) |

| Evaluation of the behavior of the convective mass transfer coefficient during drying of jaggery. | Tiwari et al. (2004) |

| Study of the convective mass transfer coefficient and rate of moisture removal from cabbage and peas (in the sun and under a greenhouse) as a function of some climatic parameters. | Jain and Tiwari (2004a) |

| Study of the effect of sample size and shape on convective mass transfer coefficient during the jaggery drying process. | Kumar and Tiwari (2006b) |

| Research on the convective heat transfer coefficient during the drying of khoa (product of India similar to cheese) in the sun and under a greenhouse (in natural and forced convection). | Kumar et al. (2011) |

Critical analysis

Up to now, the dynamic mathematical models proposed for greenhouse solar dryers have been mainly theoretical and describe the drying rate of an agricultural product or the behavior of the microclimate variables inside the dryer. Normally, these models are evaluated using data collected in experiments; however, they have not been the result of applying all the stages that the procedure for generating dynamic system models includes (van Straten, 2008). No studies have been found in the literature on sensitivity analysis, parameter estimation (calibration), uncertainty analysis and evaluation related to solar dryers. These analyses are required to determine the behavior of the models and increase the reliability of their predictions before being used in design, optimization and control. Nor has it been explored to what extent the predictive quality of a dynamic mathematical model can be improved by data assimilation methods such as non-linear Kalman filters, particle filtering and variational data assimilation. Therefore, this may be a new line of research. In addition to developing dynamic models, systems theory must be applied to generate realistic models.

The finite difference method is the most used to solve non-linear ordinary differential equations proposed by some authors to account for the change in the temperature variable and humidity of different components of the dryer system (Janjai et al. 2009; Janjai, 2012). One possible line of research is the use of classical numerical methods such as Euler’s, the second-order Runge-Kutta, the fourth-order Runge-Kutta or methods for stiff systems for the integration of non-linear ordinary differential equations (Press et al., 1997). These methods are available in simulation environments such as Matlab-Simulink, Fortran Simulation Translator (FST), and R programming language, among others. Also, they can be coded with a generic programming language like C or FORTRAN.

However, dynamic greenhouse solar dryer models have rarely been used in the approach and solution of dynamic optimization problems through the application of optimal control theory. This is a possible line of research, as the solar dryer can be operated optimally by making minimal use of energy. Optimizing drying time can also be sought by combining solar energy with other energy sources (Gallestey & Paice, 1997).

There are few studies focused on the use of artificial neural networks, fuzzy logic systems and neuro-fuzzy models for modeling greenhouse solar dryers. The main advantage of these methods is that they allow obtaining a mathematical model of the system from experimental data of the input and output signals without needing to have a detailed knowledge of the physical processes that occur in a SSSTI. In addition, the process for generating these models is shorter compared to the time required by a mechanistic or CFD model. Regarding autoregressive models with exogenous inputs (ARX), they can be used as an alternative to mechanistic or theoretical models to optimize and control the solar dryer and the drying process.

On the other hand, it is important to emphasize that the study of greenhouse solar dryers using CFD remains a field of interest, since to date this method has not been addressed in detail and the little research that exists has focused on the dryer without product inside. In addition, the design of this type of technology has usually been used in the experimental approach, because determining the behavior and efficiency of a design with certainty requires the construction of scale models. This requires long periods and even considerable budgets for obtaining precise results.

The results derived from CFD simulation allow us to know, in a fast and economical way, the behavior of the microclimate variables inside the dryer as a function of its design variables In other words, it is possible to know the spatial behavior (spatial variation) of the temperature (of the air, cover, ground and product), humidity and air speed and direction as a function of the geometry of the dryer (flat roof, parabolic, spherical, among others), its orientation, the ventilation mechanism, the physical properties of the materials and the dimensions of the prototype. The results produced by CFD constitute a reliable basis from which it is possible to consider new measures for the design of greenhouse solar dryers. Therefore, two-dimensional or three-dimensional CFD models have enormous potential, not only to better understand the spatial behavior of the variables of interest, but also to improve the design and optimize this system.

Conclusions

Multiple theoretical and empirical models have been developed for the simulation of processes and variables within a greenhouse solar dryer. However, there is limited research related to the application of this type of model in the management of solar dryers by the application of different control algorithms and systems and control theory approaches (such as classical, optimal, predictive, adaptive and intelligent control) to achieve the desired performance. Therefore, the development of control systems to improve the performance of greenhouse solar dryers is a line of research to be developed.

In order for dynamic models of the solar dryer environment to be a tool to better understand its operation and to be useful for designing, optimizing and controlling it, the generation of its structure must be complemented by sensitivity analysis, calibration, evaluation, uncertainty analysis and data assimilation.

Thin layer models are difficult to use in greenhouse solar dryers, since they are structured as a function of time; however, the most important parameter to consider is global radiation, because the temperature inside the dryers largely depends on it. Therefore, it is necessary to generate models of this type that include in their structure the behavior of radiation throughout the day.

Mathematical models that allow us to study the spatial behavior of a greenhouse solar dryer, represented by partial differential equations, use numerical solutions based on computational fluid dynamics (CFD), which have only been applied in an incipient way. Therefore, there is great potential for CFD to become a very important research tool that can contribute to the generation of a solar dryer design with a more appropriate interior distribution of climatic variables.

texto en

texto en