Introduction

Acute bacterial nephritis (ABN), formerly known as acute lobar nephronia and first described by Rosenfield,1 is a bacterial infectious process of low prevalence that affects the renal parenchyma. It is caused by different infectious agents that reach the kidney through ascending invasion or hematogenous spread.2Escherichia coli (E. coli) is the most commonly isolated etiologic agent. 1,3,4 Hematogenous spread appears to be an important infection mechanism for ABN, and wedge-shaped lesions on the renal parenchyma suggest bacterial emboli dissemination.5

ABN shares the same clinical features as acute pyelonephritis (APN) and both may present with fever, flank pain, pyuria, bacteriuria, and leukocytosis.3,4,6,7 Therefore, imaging studies are needed to differentiate between ABN and APN. The main sonographic findings in ABN are hypoechoic lesions with irregular, poorly defined margins, which may be associated with nephromegaly or perinephric fluid. Hyperechoic lesions may also be present.8,9 Ultrasound (US) sensitivity and specificity have been reported at 74% and 56.7%, respectively.10 Contrast computed tomography (CT) is the imaging study of choice, with a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 86%,11 but may be reserved for cases in which US is inconclusive.1,12

The majority of case series reported to date focus on pediatric patients, demonstrating a strong association between ABN and vesicoureteral reflux in 40% of cases.2,7,13 Acute inflammation, edema, and diffuse leukocyte infiltration are histopathologic findings in ABN, as well as in APN.4,6,14,15

It is important to differentiate ABN from other infectious renal processes because a more aggressive and prolonged treatment is required and there is also a high risk of renal abscess progression.15 Few case series on ABN in adults are available, but at present, greater access to imaging studies has resulted in increased awareness and diagnosis of the disease.

Materials and methods

Study design and definitions

A descriptive, retrospective case series was conducted. Patients were searched in our database according to keywords related to ABN diagnosis. A total of 32 clinical files from 2009 to 2016 were reviewed for cases of ABN that met the inclusion criteria described below. Data regarding clinical features and laboratory findings were obtained from the clinical records. Complete blood count, blood chemistry, and urinalysis were carried out on all 32 patients. The imaging studies of each patient were reviewed. Once patients were admitted to the hospital and treatment was begun, hospital stay and clinical progression were assessed up to hospital discharge. The present study was classified as risk-free by the hospital ethics committee.

Definitions

ABN was identified when the patient presented with fever, flank or abdominal pain, and abnormal urinalysis (pyuria and positive nitrite test), together with the following imaging criteria: 1) Contrast CT with wedge-shaped lesions, low contrast enhancement, and no cortical rim sign, 2) MRI with non-enhanced lesions on T1w or hypointense signal lesions on T2w, and 3) US with a reduced Doppler signal, associated with hypoechoic or hyperechoic wedge-shaped lesions.8,16 ABN was categorized as acute focal bacterial nephritis (AFBN), when only one lobe was affected, and as acute multifocal bacterial nephritis (AMBN), when two or more lobes were affected.

Clinical features, such as obesity, were defined, according to the CDC criteria (BMI ≥ 30),17 diabetes was defined, according to the 2018 ADA criteria (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl or random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl plus classic symptoms of hyperglycemia and/or hyperglycemic crisis),18 and hypertension, in accordance with the JNC 8 report (blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg).19 Renal function was assessed utilizing the Cockcroft-Gault formula and chronic kidney disease (CKD) was considered when the patient presented with a GFR < 60 ml/min.

Exclusion criteria

Patients whose imaging studies did not meet the definition or inclusion criteria for ABN described above, or whose studies were inconclusive, were excluded, as were patients that presented with pyelonephritis or lower urinary tract infections.

Imaging

The imaging studies of all 32 patients were reassessed and checked for diagnostic consistency with ABN, in either the focal or multifocal presentation, ensuring that the patients were accurately diagnosed through the imaging study. The diagnosis was first checked in relation to the imaging report made by the radiologist, and we carried out further investigation to make sure that either focal or multifocal nephritis was present. Images were stored in Carestream Vue PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication System) and GE Health Centricity PACS databases.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed to determine normality. All variables were collected and analyzed utilizing IBM SPSS version 22.0 software (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

The clinical records and imaging studies of 32 patients with ABN were evaluated. The majority of patients were women (n=29, 90.62%) and mean patient age was 36.34 years (SD ±13.23). The associated comorbidities were diabetes (n=16, 50%), obesity (n=9, 28.25%), hypertension (n=2, 6.25%), and CKD (n=2, 6.25%). Fever (n=15, 46.87%) and leukocytosis (n=27, 84.38%) were the main clinical findings upon admission and the mean leukocyte count was 16.77 k/µl ± 7.33 (Table 1).

Table 1 Clinical and demographic features.

| Demographic features | ||

| Age; mean ± SD | 35.6 ± 14.5 | |

| AFBN n (%) | 15(46.87%) | |

| AMBN n (%) | 17(53.13%) | |

| Women; n (%) | 29 (90.62%) | |

| DM2; n (%) | 16 (50%) | |

| HT; n (%) | 2 (6.25%) | |

| CKD; n (%) | 2 (6.25%) | |

| Smoking; n (%) | 11 (34.37%) | |

| Alcohol; n (%) | 8 (25%) | |

| Obesity; n (%) | 9 (28.25%) | |

| Clinical features upon admission | ||

| Temperature (ºC); mean ± SD | 37.82 ± 1.16 | |

| Leukocyte count; mean ± SD | 16.77 ± 7.33 | |

| Creatinine; mean ± SD | 1.04 ± 0.71 | |

AFBN: acute focal bacterial nephritis; AMBN: acute multifocal bacterial nephritis; CKD: chronic kidney disease; DM2: diabetes mellitus type 2; HT: hypertension; SD: standard deviation.

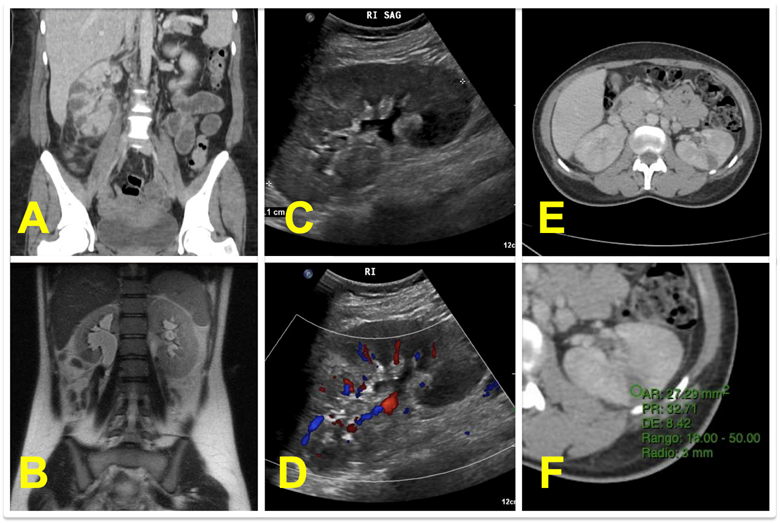

The available CT, US, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies were reassessed for each patient. Only 5 patients (15.62%) had an inconclusive US, requiring CT, and in those cases, the CT was utilized for the re-evaluation because it is a more sensitive imaging study. Abdominal contrast CT was performed on 59.38% (n=19) of the patients, ultrasonography on 37.5% (n=12), and MRI on 3.12% (n=1). One female patient had a single MRI study because she was pregnant. Imaging features required for diagnosis are specified in our inclusion criteria, examples of which are shown in Figure 1. Seventeen (53.13%) patients presented with AMBN, whereas 15 (46.87%) presented with AFBN.

A) Contrast CT of right AMBN. B) T2w MRI of AFBN in the right lower pole. C) US of AFBN in the left lower pole. D) Doppler US showing no signal in the same patient. E). Contrast CT of left AFBN. F) Attenuation rate of previous image between 20-45 HUs (32.71 HUs).

Figure 1 ABN imaging

ABN: acute bacterial nephritis; CT: computed tomography; AFBN: acute focal bacterial nephritis; AMBN: acute multifocal bacterial nephritis; HUs: Hounsfield units: MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; US: ultrasound.

Intravenous antibiotics were used in all the cases. The most common combination in our study was a third-generation cephalosporin plus an aminoglycoside (n=10, 31.25%). Other antibiotic therapies included beta-lactams alone (n=9, 28.12%) and third-generation cephalosporins alone (n=7, 21.87%) (Table 2). Antibiotic therapy had to be escalated to carbapenems in 25% (n=8) of the patients, and a single case required nephrectomy (3.12%).

Table 2 Association between clinical progression and treatment.

| Hospital stay; mean ± SD | 7.84± 6.91 |

| Mortality; n (%) | 2 (6.25%) |

| Progression to renal abscess; n (%) | 3 (9.37%) |

| Treatment | n (%) |

| Beta-lactams | 9 (28.12%) |

| 2nd generation cephalosporin + aminoglycoside | 1 (3.12%) |

| 3rd generation cephalosporin | 7 (21.87%) |

| 3rd generation cephalosporin + aminoglycoside | 10(31.25%) |

| Aminoglycoside | 2 (6.25%) |

| Other | 3 (9.37%) |

SD: standard deviation.

Etiologic agents were isolated in urine cultures in 34.38% (n=11) of the patients. E. coli (n=7, 63.63%) was the most commonly isolated bacterium in the positive cultures, followed by coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (n=2, 18.18%). The remaining isolated agents were K. pneumoniae, E. faecalis, P. aeruginosa, and Candida. Anaerobic blood culture was not routinely carried out.

Hospital stay was 7.84 ± 6.91 days and there were 2 deaths. Progression to renal abscess was observed in 9.37% (n=3) of the patients. The data is shown in Table 2.

Discussion

In the present case series report, we describe the clinical and imaging features, as well as the clinical course, of ABN, in either its focal or multifocal presentation. Imaging studies are mandatory for ABN diagnosis. Distinctive findings on contrast CT imaging are wedge-shaped hypodense lesions that exhibit no capsule and no contrast enhancement. Absence of the cortical rim sign helps distinguish between focal nephritis and renal infarction,20,21 and signs of perinephric inflammation, such as fat stranding, can also be observed. Density measurement between 0-20 Hounsfield Units (HUs) may help distinguish ABN from renal abscess, only when parenchymal necrosis tends to be liquid, because densities of kidney parenchyma and pus may overlap between 20-45 HUs. MRI, although not routinely used, shows hypointense T2w lesions and low enhancement in T1w sequences.20 Sonography shows wedge-shaped lesions with a low or absent Doppler signal. Hypoechoic lesions are the most likely findings, but hyperechoic lesions may be present in some instances.20,21 Figure 1.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no specific guidelines for ABN, given that the etiologic agents related to the infectious process are the same as those in APN. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for APN recommend 2nd and 3rd generation cephalosporin (cefuroxime or ceftriaxone), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin), or aminoglycosides (gentamicin, amikacin) as first choice IV treatment for the severely ill patient, and combinations are possible, depending on susceptibility.22 Empiric treatment should be initiated, according to the most commonly found bacterium. A mid-stream urine sample should be taken for gram staining, culture, and antibiogram. In our case series, the most common antibiotic combination was a 3rd generation cephalosporin plus an aminoglycoside (ceftriaxone + amikacin), observed in 31.25% of the cases.

In a systematic review, Sieger et al.20 assessed 138 cases of ABN and reported features similar to those in our study. The cardinal clinical characteristics were fever, leukocytosis, and flank pain and E. coli was also the most commonly isolated etiologic agent. Those authors recommend conservative treatment, 2 weeks of oral antibiotic therapy after discharge, and then sonographic follow-up. Some of our patients were ineffectively treated before arriving at the emergency department, which could be related to the quantity of negative urine cultures reported in our case series (65.62%). A positive urine culture is not mandatory for the diagnosis of urinary tract infections. 23 All of our patients had urinalyses that were consistent with urinary tract infections and the 32 cases of ABN were confirmed through imaging studies.

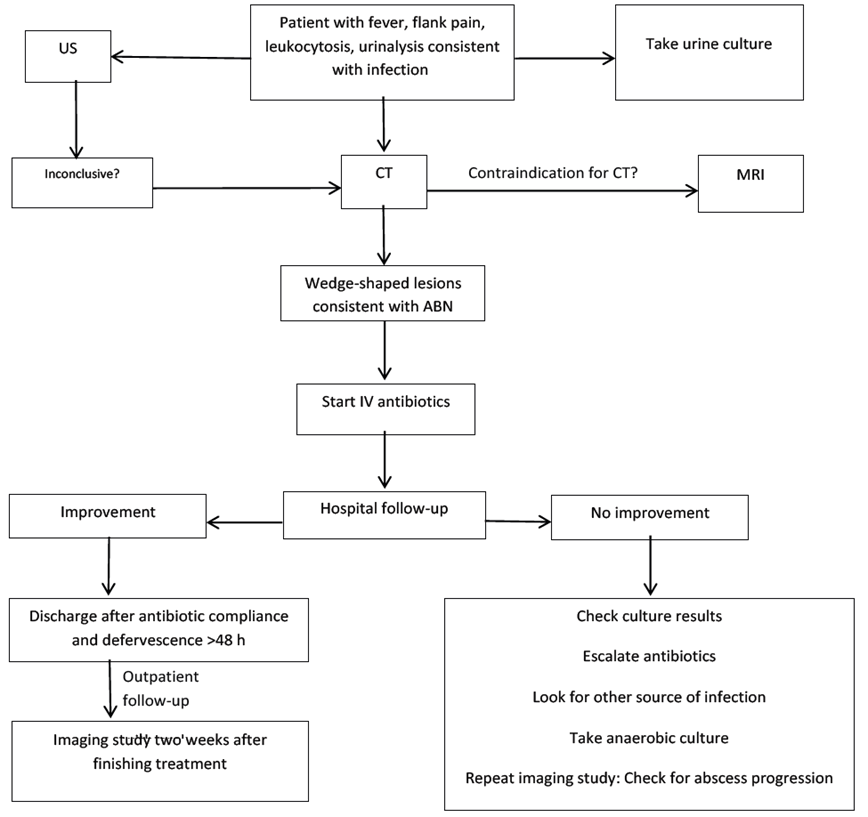

An advantage of our study was the description of clinical characteristics and imaging features of the two presentations of ABN, an underdiagnosed entity. The recent interest in ABN has raised awareness in differentiating it from APN, considering it a midpoint between APN and renal abscess.24 Our patients were given IV antibiotics for 7.84 ± 6.91 days, concurring with the EAU guidelines, which recommend IV antibiotic treatment for 7 to 14 days.25 Patients were discharged from the hospital after 48 hours of defervescence (Figure 2). No differences between the focal and multifocal presentations were observed.

Conclusions

The limitations of our study include its retrospective design, the small sample size, and the fact that not every patient had a standardized imaging study workup. Only 3 patients developed renal abscess, which hindered the progression analysis.

Our study showed that early and aggressive IV antibiotic therapy was effective in ABN management. There should be high clinical suspicion of ABN in all patients with presumptive APN, given that it presents with greater morbidity. Imaging assessment is crucial.

We reviewed 32 cases of ABN at our institution in the present analysis, and our results were similar to findings in other studies.1,6,8,20,26,27

We believe more studies showing that ABN is a different entity from APN are needed. The comparison of the two presentations has not been analyzed in depth, and their distinction can change patient prognosis and outcome.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)