For the more than a quarter of a century before approximately 2017, economic growth in the People’s Republic of China [PRC] led to it being regarded by almost all the governments of the more developed countries of the world as at the very least an economic partner of considerable merit. Some, like the then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, David Cameron and his Treasurer went even further towards the recognition of a cargo-cult describing their new relationship with China as establishing a ‘Golden Era’ (Reuters, 2015). Certainly, the attraction of cheap labour in a growing manufacturing environment, the increase in machinery and heavy industrial development, and the prospect of a rapidly expanding consumer market were all drivers of economic globalisation at that time, with the PRC at its heart. In the last four years though this promise has been replaced, at least in the public discourse in many of the same countries, especially in the USA, the UK, Australia, and across Western Europe by concerns that China represents a threat to the rest of the world. The drama of the new China Threat is that it is not just represented as a challenge to economic production elsewhere in the world, with entailed disruptive consequences for workers and capital. China is now said to pose a strategic and military threat to the peace of the world, from a country (and its government) which will not observe the current rules of the international order. China is now regarded by many as an existential threat, in the words of the then Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull in 2017 ‘to our way of life’ in introducing his country’s new foreign policy (Australia Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2017).

An examination of the various claims that China presents an existential, a military, or an economic threat to the rest of the world are largely unfounded. Despite the parallels that are sometimes drawn between China today, on the one hand, and Nazi Germany or Showa Japan, on the other, in the 1930s, China’s rise as an economic power has no imperial ambition in either the European or the American mould. The PRC is certainly driven by a desire to be recognized as a global power and to be internationally influential. It has certainly become more assertive internationally under Xi Jinping, the current President of the PRC and General Secretary of the Communist Party of China [CCP]. At the same time, the claimed China Threat rapidly disintegrates on closer inspection to reveal challenges that leaders of influence (politicians, journalists, and sometimes even academics) outside the PRC sometimes find hard to deal with appropriately, preferring instead either to embrace the political opportunism represented by the consequences of a ‘rising China’ in their domestic constituencies or out of concern for their own narrow national economic interests, or indeed both. This is clearly the case for those in the USA who have taken the leading position in the development of the myth of the China Threat. The irony of course is that the increased opportunity for economic integration presented by the same ‘rising China’ may actually be of greater benefit to each country’s citizenry than the economic protectionism promised through offers along the lines of ‘Make America Great Again.’

The Existential Threat

The now often-cited development of a new Cold War between the USA and the PRC speaks to the existential threat that some people outside China believe is the present and the future of relations between the two countries, and indeed between China and other parts of the world. In the Cold War the faceoff between the Soviet Union [Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, USSR] and the USA was clearly an existential threat. The USSR presented an alternative politics, and alternative government, economic and social systems, not only different to the USA and its brand of liberal democracy, but also both seeking to replace it, and, as the experience of Eastern Europe post-1945 proved in the extreme, willing to expand beyond its initial borders.

In the new Cold War China is equated not only with the USSR as was, but also with Nazi Germany and is described as they were as both an ‘Orwellian police state’ and totalitarian (Hoover, 2021, p. 2). Both aspects of that characterisation are important. In that view, the population is totally controlled in every way by the Communist Party of China [CCP] and politics is everything, there is no space for a separate society which is totally subsumed by the state (Schapiro, 1972). As a result, there is no room to argue that Chinese people are to be differentiated from the government system of the PRC, let alone the CCP. As the Director of the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI] is reported as having said in testimony to a USA Senate Intelligence Committee ‘China is not just a whole of government but a whole of society threat on their end’ (Redden, 2018). Moreover, in the USA at least anti-communism is clearly an important aspect of the new Cold War against China which is held to threaten ‘the free world’ and capitalism, and unsurprisingly the same organisations associated with fighting the earlier Cold War, such as the Hoover Institution, are now in the vanguard of the new politics (Diamond & Schell, 2018; Hoover, 2021).

Certainly not every leader of influence in either the USA or elsewhere thinks that China is any kind of existential threat (Bade, 2021; Swaine, 2021a) or indeed that the existential threat is to be experienced in quite the same way as that provided earlier by the USSR. In early May 2021, the one-time Republican presidential candidate in the USA Mitt Romney argued that ‘We (the USA) can’t look away from China’s existential threat’ in the following terms:

China will replace America. China is on track to surpass US economically, militarily, and geopolitically. These measures are not independent: A dominant China economy provides the wherewithal to mount a dominant military. Combined these will win for China the hearts and minds of many nations attuned to their own survival and prosperity. (Romney, 2021)

There are though held to be some common key markers in the challenge said to result from China’s increased economic strength and political assertiveness, in addition to the more obvious military and economic considerations (to be considered in each of the next two sections). One is the ideological conflict between democracy and authoritarianism; a second is Beijing’s perceived challenge to the international rules-based order, which it is claimed sustains global stability; and a third is the claim that China engages in considerable overseas influence operations in other countries that amount to interference and the subversion of the domestic politics of other countries.

Ideological Conflict

The direction of these claims is hard to understand, and they remain largely unsubstantiated in detail. While it is undoubtedly the case that the PRC is a Communist Party-state, the CCP has clearly embraced the importance of the market and capitalism, domestically and internationally. There are those who argue that the success of the PRC in the last few decades has come from its embrace of capitalist practices (Halper, 2010). While not everyone would agree with such statements, even if its variety of market socialism has emerged from state socialism, and adapted aspects of state capitalism (notably the continuation of a limited if still significant state sector of the economy with state-owned enterprises) large parts of the Chinese economy are more like free market capitalism than any form of socialist economic system. The former socialist working class has shrunk in size, and in economic and definitely political importance. Its place has been taken by a new precariat working class of migrant rural workers (Blecher, 2021). There remains a small state sector of less productive enterprises, though they too are subject through the CCP’s political leadership to economic competition and market forces (Naughton, 2010) and eight of the remaining 97 national state-owned enterprises (managed through the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission) are listed on the three leading stock exchanges in the USA (US-China Economic Commission, 2021).

Since the start of the Reform Era in 1978, the PRC has dropped all claims to exporting revolution, and indeed adopted an oft-repeated policy of non-intervention in the affairs of other countries. While the topic is much debated with the PRC, nonetheless the basic premise is still maintained (Zheng, 2016). As Rana Mitter has recently pointed out, interdependence “is at the heart of the PRC’s contemporary international relations. Moreover, “Socialism with Chinese characteristics” (the formula for the Reform Era) is, by definition, not a system that can be reproduced elsewhere’ even if certain of its experiences, such as poverty reduction, might be useful to other countries (Mitter, 2021).

At the same time, PRC foreign policy has moved from the earlier more passive stance advocated by Deng Xiaoping to ‘keep a low profile’ (Taoguangyanghui) internationally (Deng, 1992). Under first Hu Jintao (to 2012) then subsequently Xi Jingping, the PRC’s foreign policy has become more pro-active in seeking to establish a ‘community of common destiny’ where the world is characterised by mutual cooperation, economic integration, and shared responsibilities as well as shared interests. This model of international relations is explicitly presented as providing an alternative to the perceived domination of the United States and its allies.

There is an obvious challenge to the USA in the notion of a ‘community of common destiny’ which implicitly suggests that the USA’s may be disproportionately influential. This is the sense in which Wang Huiyao, head of the China Centre of Globalisation has written that ‘China is both an engine for global economic growth and a contributor to global order’ (Wang, 2021). One consequence of this push is that some in the USA have accused the PRC of not abiding by and threatening the rules of the international order (Hoover, 2021, p. 1) and this has led to an international relations academic literature considering whether in more polite language a rising China is a norm-taker or a norm-maker (Reilly, 2012). Somewhat surprisingly perhaps, the evidence of independent research is that the PRC has long been a far better upholder of the rules of the international order than the USA, though clearly China is also trying to both limit the leading position of the USA and to create new procedures and patterns of acceptable behaviour that to some extent privilege its position rather than that of the USA (Kent, 2007; Johnston, 2008). The Belt and Road and the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank are new PRC-led initiatives to that end, though they exist alongside the PRC’s participation in the structures of the established international order through Climate Control discussions (Gippner, 2020) and significant contributions to the UN Peace-keeping Force (Gowan, 2015).

Influence and Interference

There are those in other countries, such as the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, who claim vociferously that China is subverting democracy elsewhere in the world through various activities including overly close relationships with foreign politicians, the development of Confucius Institutes, the spread of the Wechat social media platform, in all of which the role of the CCP’s United Front Work Department and other state and Party agencies feature prominently (Joske, 2020b; Joske et al., 2020). A similar argument is made about the unsafe cooperation between universities and their academic staff and researchers in, on the one hand, China, and on the other, different parts of the world. Here the argument is that ideas, technology, and discoveries are being stolen or being used to inappropriate purposes by the PRC (Cave et al., 2019; Burton, 2021; Hoover, 2021).

Some of those voices that are concerned about or opposed to China’s increased role in international politics accept that the attempt to create influence in another country is not the same as interference. In the USA for example, claims of Russian interference in the 2016 Presidential Election were well-publicised. Yet a Hoover Institution report still explicitly indicated that the PRC had not engaged in that kind of activity (Diamond & Schell, 2018). Yet others fail to make the distinction - in the USA, those who have argued strongly that Confucius Institutes should be closed in universities, in particular the Presidency and State Department under President Trump (Riechmann, 2020; Redden, 2020); in Australia the attention of similarly-minded critics focuses on politicians, academics, and the Chinese language media, notably instigated through the work of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (Hanson et al., 2020; Joske 2020a; Joske et al., 2020).

There is a clear need for a broader perspective on these various influence activities. It seems unlikely that the Confucius Institutes are any more dangerous than other examples of cultural diplomacy such as the UK’s British Council offices, or the USA’s USIS [United States Information Services] (to 1999) though of course there have been times and places when and where both those were regarded as agents of foreign interference, some even in recent memory: for example, Hong Kong, 1955 (Oyen, 2014); Russia, 2008 (Reuters, 2008); Iran, 2019 (PressTV, 2019). Propaganda is in any case universal and it would be self-defeating for an open society to attempt to restrict or censor information flows, regardless of the source. Not to mention that repression of ideas usually proves counter-productive: as for example, with the impact of persecution on the early Christians in Ancient Rome, or resistance to Buddhism in China during the 6th and 9th Centuries. Similarly, attempts to limit scientific and technological cooperation with researchers in the PRC are misplaced. The development of science and technology is a universal public good, though specific applications may and should clearly be subject to the authorisation and control of particular states.

Political Opportunism

Many of these claims that China constitutes an existential threat clearly play well with some politicians as well as with electorates whose voters have lost out for some time to the processes of economic globalisation, technological change, and climate change. Citing China as responsible for the social and economic disruptions that result is easy if not exactly responsible. At the end of the day, sending manufacturing to locations where labour is cheaper only makes sense if states are prepared to redistribute (usually through taxation) the wealth that is created. Tariff wars and protectionism do not meet populist expectations under such circumstances since the result will be a decline in the working populations’ standard of living (Marchand, 2017). Reducing fossil fuel capacity similarly will only prove politically acceptable if state intervention provides assistance, as in Germany (Bundesrat, 2020). And as with manufacturing and services, technology is not nationally determined but subject to the global market, with the same consequences. China, and its dramatic economic growth patterns of the last few decades, may well be at the centre of some of these activities. At the same time, as the opposition spokesperson on foreign affairs in Australia recently pointed out, domestic fear-mongering is not just socially and economically irresponsible; it is also politically counter-productive, internationally always and domestically in the long-term (Wong, 2021).

In Australia, the China Threat has indeed become manifest through precisely the emergence of such political opportunism. Max Suich recently described that process in after 2017 under Prime Ministers Malcolm Turnbull (2015-18) and Scott Morrison (since 2018):

Quite early, the domestic political advantages of a China threat narrative were grasped by coalition ministers and advisers. It would play to the Coalition’s polling strength as a defender of national security. The alp could be wedged as a friend of Beijing. Washington would approve. For Malcolm Turnbull, re-elected with a bare majority of one, the hawks of the Abbott rump of the Coalition backbench would be mollified. In 2021, domestic political advantage is now a key driver of China policy. (Suich, 2021)

In the USA at the end of April 2021 the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee approved the bipartisan Strategic Competition Act 2021 specifically designed ‘to address issues involving the People’s Republic of China.’ This act has with some justice been described within the USA as one that ‘constitutes a de facto declaration of a cold war with the People’s Republic of China’ (Swaine, 2021b). Subsequently the Strategic Competition Act has been combined with the Endless Frontier Act and the Meeting the China Challenge Act (with additional inputs from the Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee, the Judiciary Committee, and the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions) in a newly named United States Innovation and Competition Act 2021 to provide policy and funding in this new cold war against the PRC (US Senate, 2021). The first two paragraphs of the Strategic Competition Act (now incorporated in wider proposed legislation) are instructive in terms of understanding the nature of the current China Threat:

Congress makes the following findings:

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is leveraging its political, diplomatic, economic, military, technological, and ideological power to become a strategic, near-peer, global competitor of the United States. The policies increasingly pursued by the PRC in these domains are contrary to the interests and values of the United States, its partners, and much of the rest of the world.

The current policies being pursued by the PRC-

threaten the future character of the international order and are shaping the rules, norms, and institutions that govern relations among states;

will put at risk the ability of the United States to secure its national interests; and

will put at risk the future peace, prosperity, and freedom of the international community in the coming decades.

Paragraph 10 echoes earlier equations of influence and interference both in the USA and elsewhere with respect to The China Threat.

(10) The PRC is promoting its governance model and attempting to weaken other models of governance by-

undermining democratic institutions;

subverting financial institutions;

coercing businesses to accommodate the policies of the PRC; and

using disinformation to disguise the nature of the actions described in subparagraphs (A) through (C).

It is clear from this proposed legislation that its proponents are concerned primarily with the challenge that China poses to the leading international position of the USA and that country’s national interests. In that process there is an equation presented of that leading position and the interests of the USA, on the one hand, and the interests of the world, on the other. Necessarily then the ideational aspects of the challenges posed by China’s increasing economic and political importance draw further attention to the consequent military and economic challenges, especially in relations between the USA and PRC.

The Military Threat

At first sight, the military and strategic threat posed by China’s economic development seems obvious, though not everyone has gone as far as the Secretary of the Australian Department of Home Affairs and a senior national security official, Mike Pezzullo, or the Australian Minister of Defence, Peter Dutton. Pezzullo it was who on ANZAC Day 2021 (the day on which Australia acknowledges its war dead) in a message to his staff later published in The Australian warned that ‘the drums of war are growing louder.’ Echoing the idea of an existential threat, Pezzullo referred to President Eisenhower’s view in 1953 that ‘as long as there persisted tyranny’s threat to freedom they (the free nations) must remain armed, strong and ready for war, even as they lamented the curse of war’ (Pezzullo, 2021). For his part, Dutton on the same day in a television interview opined that ‘war with China over Taiwan could not be discounted’ and then a week later in a newspaper interview commented that ‘the Australian Defence Force was prepared for action, saying the country needed to be in a position to defend its waters in the north and west as a clear priority’ (Galloway, 2021).

Certainly, the PRC has increased its defence expenditure, and perhaps more importantly professionalised its military and upgraded its military technology with the changed economic development strategy since 1978. Indeed, modernisation of the People’s Liberation Army [PLA] was central to that change before even it was formally approved as a policy by the CCP. That process has continued over the intervening decades with news leaking out in May 2021 that the PRC would have stealth bombers capable of reaching the US territories of Guam and the Mariana Islands in the North-west Pacific by the end of the decade (Huang, 2021). Even more dramatically though the apparent military, and to some extent expansionist or imperialist threat is said to be found in the PRC’s attitude to the South China Sea and over the future of Taiwan. At the same time, in both cases while the problems inherent in each are real enough the lack of perspective in determining China as a threat rather than a challenge open to negotiation is possibly of greater concern.

The PRC’s claimed maritime boundaries have from the establishment of the new regime in 1949 included both the majority of the South China Sea and the island of Taiwan. These claims result not just from a historical narrative fundamental to the nationalistic ideology of the CCP with its roots in the late Qing Dynasty -as is the case with its land borders (Shabad, 1956)- but also from a shared narrative with the Nationalist Party and the Republican Government, first in civil war and then later when the Nationalists fled to Taiwan. Contemporaneously, while there is military presence in or close by both locations, there is also government-level negotiation. The PRC’s military activities in the South China Sea may have certainly increased in the last decade, but the increase in tension over Taiwan seems to have resulted from an increased threat assessment in Washington.

China has claimed jurisdiction over the South China Sea since 1947 when the then Government of the Republic of China included the large maritime area to the south of China’s landmass in its maps. This area was demarcated by an ‘eleven-dash line,’ as indicated on maps of the region at that time. The area covers some 3.5 million square kilometers, and something like 250 largely previously uninhabited islands and rocks. The South China Sea is long disputed amongst the surrounding governments including the PRC, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, Brunei and Indonesia, all of whom (except Brunei) have occupied or developed islands and other features. Vietnam has the largest number of control points (21). During 2013-2018 the PRC developed military bases, naval facilities, and airstrips, and built artificial islands in the Paracels and Spratly Islands, and has made to develop the Scarborough Shoal off the coast of the Philippines.

At issue amongst the claimants to parts of the South China are fishing and mineral rights as well as trade routes, though many countries from outside the immediate region (the USA, Australia, France for example) have also been involved in discussion of the control of shipping corridors. The latter has become particular important in the last few decades, generally and particularly for China. About a third of all world sea trade passes through the South China Sea, 40 percent of China’s total trade and most of its energy imports. Despite the occupation of islands and development of military facilities, government negotiation rather than military confrontation has characterised disputes. There have been no military engagements even over contested occupations since 1988. In 2000 China and Vietnam agreed on zones of control in the Gulf of Tonkin, which amongst other things reduced the ‘eleven-dash line’ to a ‘nine-dash line’. A Code of Conduct between China and ASEAN [the Association of Southeast Asian Nations] is currently being negotiated (Kaplan, 2014; Hawksley, 2018; Scobell, 2018; Strangio, 2021). Perhaps even more remarkably, despite winning in an arbitration under the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea in 2016 against PRC activities off The Philippines, in May 2021 Rodrigo Duterte, President of The Philippines described the ruling as ‘trash’ and ‘a waste of time and at the same time disrupting the good relations of China and the Philippines’ (CNN, 2021).

Conflict over Taiwan is even more complex, though surprisingly despite all the sabre-rattling now and in the past, even more devoid of military engagement. The PRC claims Taiwan as a ‘renegade’ province, probably less because of late Qing history -Taiwan was designated a province from 1887 to 1895 before being ceded to Japan (van der Wees, 2020)- than because of the history of the Republican Government. Taiwan was returned to China after the Second Sino-Japanese War (World War II) in 1945, and when defeated on the mainland in 1949 the Nationalist Party took the Republic of China and its governmental system to Taiwan with the promise of returning and re-uniting the country. This formula lasted until well into the era of open political competition on Taiwan in the 1990s, and the questions of independence and the relationship with Mainland China remain unresolved and contested in domestic Taiwan politics. Many argue that Taiwan has never or rarely been part of China, while others argue for self-determination and others still for constructive cooperation of various kinds with the PRC (Cole, 2021; van der Wees, 2021). In a clear example of strategic ambiguity, the government of Taiwan is still formally described as the Republic of China.

While the East China Fleet and other forces of the PLA have long held annual exercises to (re)take Taiwan, the CCP has always seen the (re)incorporation of Taiwan as to be solved politically not militarily. There are several reasons for this beyond the most obvious shortcomings that might result from an invasion strategy: the lack of effective military capacity to take and hold Taiwan; loss of international profile; and the dangers of a wider conflict; not to mention the end of economic and technological cooperation across the Taiwan Straits (Parton, 2021). Above all though the CCP has always acted to discourage Taiwan independence believing that reunification might be achieved through peaceful means on its terms. The threat of military action fits into that strategy as a more potent weapon than armed conflict. In early 2019 when Xi Jinping last focused to any extent on the Taiwan question he linked his goal of ‘national rejuvenation’ with the peaceful reunification of Taiwan but with only the vague goal of achieving this by 2049, presumably because that would be appropriate for the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the PRC (Xi, 2019). These considerations have though not stopped military interests in the USA from arguing not only that the CCP under Xi Jinping is preparing to launch an attack on Taiwan, but that this will occur in the immediate future. In early 2021 these views were reported to the US Senate Committee on Armed Services (US Senate Armed Services, 2021). This seems to be the origin of the current wave of heightened emotion both in the USA and in Australia, where these views were echoed in particular by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute prior to the comments by Pezzullo and Dutton (Jennings, 2021; Herscovitch, 2021).

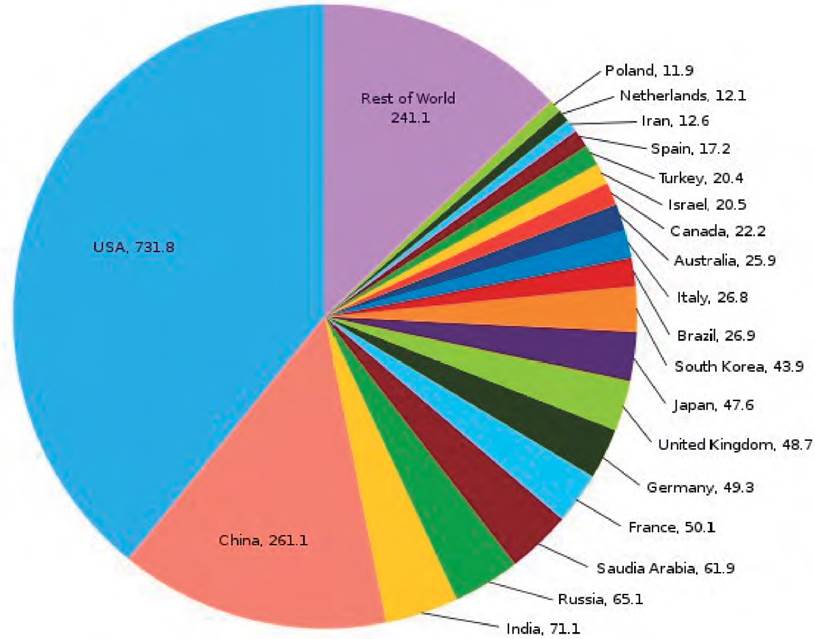

This lack of perspective about the military challenges posed by the PRC is with one exception further evidenced by comparative data on military expenditure and military hardware capacity between the USA and the PRC. Figure 1 provides information about military expenditure by country; Figure 2 a comparison of military capacity for the USA, UK, and PRC. In 2020 world military expenditure was approximately US$1,981, with 39 percent being spent by the USA and 13 percent by the PRC. In 2020, the USA increased its military expenditure by 4.4 percent, the PRC by 1.9 percent (Lopes da Silva et al., 2021). USA military expenditure is 3.1 percent of GDP at nominal value; the PRC’s represents 1.9 percent. Differences in military expenditure are reflected in fairly obvious differences in military capacity. The comparison with the UK in Figure 2 is instructive: the PRC is closer to a middle-ranked power than to the USA. The one exception to the obvious conclusion is of course that while the PRC is to date a regional military power, with its focus on East Asia; the USA has a more global military deployment perspective. While clearly an argument is being made in Washington for increased military expenditure, the extent of the challenge from the PRC needs to be kept in perspective.

The Economic Threat

As with the military threat from the PRC, consideration of the economic threat is similarly lacking in perspective. Much is made of the point at which the PRC’s GDP will exceed that of the USA. Estimates are currently that this will occur in a few years’ time: 2026 according to Fortune magazine (Elegant, 2021); 2028 according to the BBC (BBC, 2020). In nominal terms the USA currently (2021) has a GDP of US$22.7 trillion, the PRC US$16.6 trillion. If adjusted for purchasing power parity, the US GDP is currently US$22.7 trillion, and the PRC’s GDP US$26.7 trillion (all information from the International Monetary Fund Dataset). There is certainly economic competition amongst the countries of the world, and even to some extent between the USA and PRC, yet the idea that China is an economic threat, especially to the USA, rather than simply a challenge to be negotiated, needs modifying. It is far-fetched to argue that the PRC economy will supplant the USA economy any time soon, not simply because of the strengths of that economy but also because of the limitations of the PRC economy. There are substantial scale differences between the economies of the PRC and the USA; a goal and strength of the PRC’s economic development strategy is its integration with the rest of the world; and despite considerable growth in the last four decades, the PRC’s economy faces its own challenges.

The difference in scale between the economies of the PRC and the USA is considerable. They may be the two largest gross GDP economies but the superior strength of the USA, even in gross terms and despite problems associated with the use of a GDP index to these ends (Feldstein, 2017) is far superior. In nominal terms, GDP per capita in the USA is US$68,309; in the PRC it is $11,819. The PRC’s GDP per capita is just below the global average of US$12,167 (International Monetary Fund). The PRC not only has a far larger population (approximately 1,439 million, compared to 331 million people in the USA) its economic geography is considerably more varied, inequality far greater, and productivity much lower (West, 2019). In the large metropolitan areas (Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen) and provinces (Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Guangdong) of the Eastern and Southeastern Seaboard economic development is advanced by any standard. Some two-thirds of the population of Jiangsu are regarded as having reached middle-class income standards in a province of 80.7 million, where the area in that province north of the Yangtze has long been noted for its poverty (Wei & Fan, 2020). While there are pockets of poverty and economic backwardness on the Eastern Seaboard and in the South of China, the areas in the Northwest and Southwest of China remain considerably less developed (Goodman, 2004). In May of 2021, at a major national discussion of economic development, Justin Lin, one of China’s leading state economists pointed out that when China’s national GDP per capita eventually does reach half that of the USA it is likely that the GDP per capita of the coastal provinces and the major Eastern Seaboard municipalities will be roughly equal that of the national GDP per capita in the USA (Lin Yifu, 2021).

The PRC sees itself as a world economy, not simply because of its size and impact, but as an economy which is well-integrated with the rest of the world for production, markets and technology. The degree of the PRC’s integration with the world economy is easily underestimated, as Donald Trump discovered when as President of the USA he attempted to engage in economic warfare against the PRC as part of his recipe to ‘Make America Great Again’. He believed that it would be possible to repatriate extraction and manufacturing industries to the USA from China and to cripple the PRC with tariffs, forgetting that much of the USA’s debt is owned by China, that the PRC hosts much US investment in manufacturing and technological development, and that in any case the PRC trades with many countries and is not as dependent on bilateral trade as the USA. The Trump goal of reducing the USA trade deficit generally and specifically with China was not achieved. On the contrary, trade deficits grew substantially and even with China by the beginning of 2020, when the strategy was abandoned (Hass & Denmark, 2020; Bloomberg, 2021). By the beginning of 2021 the previous four years had seen the three largest US trade deficits in its history; November 2020 saw the largest US trade deficit in 14 years, while China achieved its highest monthly trade surplus ever in December 2020. The US-China Business Council (representing those US companies operating in the PRC) pointed out not only the lost financial returns to the USA but also the loss of half a million jobs in the USA (Bartholomeusz, 2021).

Despite the disaster of the Trump Presidency’s economic relations with the PRC, the US economic remains strong, which points to the political opportunism of highlighting a hostile relationship to China, as opposed to economic desperation. For its part, the PRC’s assessment of its own economic performance is more measured. While it is clear that in some areas, especially of new technologies such as AI, batteries, electric vehicles the PRC is now world-leading (Yergin, 2020), problems remain. As already noted, the dangers of severe inequality are well-noted (Milanovic, 2021). In addition, there are frequently articulated concerns about the extent of local government debt; of access to crucial supply chains, especially those related to technology; and of the decreasing share and quality of the manufacturing sector. While about 30 percent of total world manufacturing is China-based, a PRC State Council Development Research Centre report in January 2021 and a speech by the former Minister of Industry and Information Technology (Miao Wei) at a meeting of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (where he is now Chair of that body’s Economic Committee) in March 2021 spelled out a series of fundamental challenges to the manufacturing sector:

China’s manufacturing sector is large but not strong, comprehensive but not outstanding -a situation that has not fundamentally changed- […] In the four tiers of global manufacturing, China is among the third-ranked countries. It will take at least 30 years to achieve the goal of becoming a manufacturing great power. (SCMP, 2021)

These comments echoed the earlier report from the State Council Development Research Centre which had classified the PRC as a third (out of four) tier country in the world for manufacturing based on a series of indicators which included quality, effectiveness, international competitiveness, environmental friendliness, labour productivity, research and development personnel in the labour force and innovation. The USA, Germany and Switzerland were in the top tier; Japan, South Korea, France and Singapore in the second tier (SCMP, 2021).

The Politics of The China Threat

The development of the PRC’s economy and its consequences for international economic and political activities certainly presents challenges to other countries both regionally and globally. On the evidence to date though it seems misleading to regard this as an existential threat. At the same time, it is clear that The China Threat as a political ideology is clearly here to stay if not forever, at least for some time. As with all strongly held-belief systems its proponents have a strong strategic view that links their views of social values, economics, and politics (including, as in this case, military matters) in mutually reinforcing interpretations of the dangers faced by the world together with the solutions to those problems.

There seem to be three principles that are the drivers of The China Threat: a resistance to understanding processes of change in general, but particularly its social and political consequences; a commitment to maintain the USA’s dominant and determinant role in global institutions and international politics; and a belief in the purity of the security forces and military interests in determining politics, domestically and internationally. Each of these is to some extent destabilising as a recipe for future world peace, but the third is actively dangerous, and conceivably more dangerous than The China Threat.

As the international experience of the USA since the 19th Century provides ample evidence, economic development is not infinitely sustainable as a one-way process which works to the exclusive advantage of the earliest, most developed parts of the world. The entire discourse that describes countries in terms of ‘rise’ and ‘fall’ and rankings is testament to more complex processes of change. In those processes, states have always experienced elements of fear of the unknown, of change in general, and of losing standing in the world. In the era of intense economic globalisation, fuelled by technological developments impacting both supply chains and information flows this resistance is almost necessarily more immediate and more intense.

The international leading position of the USA has been a key feature of the world since 1945 and the end of the Second World War. A certain amount of almost justifiable triumphalism on this count crept into US politics after the collapse of the USSR and the end of the Cold War. Reactions to any potential challenges, real or imagined, to the USA’s position in international politics from within the USA, such as that reported earlier by Mitt Romney, are then to be expected. Within the USA the equation between the interests of the USA and the interests of the world are even understandable from the same perspective. More remarkable though is the acceptance of this estimate of the USA’s international importance from leaders of influence in other countries. In the United Kingdom, a number of Conservative Party members of parliament formed the China Research Group as a prime advocate of The China Threat in opposition to the PRC and supporting the USA (Payne, 2020). In Australia, a group of parliamentarians from both the Liberal and Labour Parties have styled themselves as the ‘Wolverines’ to the same ends (Curran, 2020).

The first of those two drivers for The China Threat are significant but not as profoundly dangerous as the role in its development played by military and security interests. One danger is that those interests will create not just an acceptance of the need for armed conflict by repeatedly talking up the likelihood, as has happened in both the USA and Australia, but also the self-fulfilling prophecy of an easy escalation of the conflict into military engagement. Another even greater danger is that military and security interests have too much influence in their domestic policy-making environments, both through their supporters in political life and think-tanks, and through their involvement in information flows. This would appear to be the case not only in the USA but also in Australia. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute describes itself as ‘an independent, non-partisan think tank that produces expert and timely advice for Australian and global leaders’ (https://www.aspi.org.au/about-aspi) despite being funded by the Australian Department of Defence, the USA State Department, and a number of companies in the arms, defence and security industries.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)