Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Medicina y ética

versión On-line ISSN 2594-2166versión impresa ISSN 0188-5022

Med. ética vol.35 no.4 Ciudad de México oct./dic. 2024 Epub 29-Oct-2024

https://doi.org/10.36105/mye.2024v35n4.04

Articles

Perinatal palliative care: a comprehensive approach

*XIMA Health & Wellness, Ciudad de México, México. Correo electrónico: ignacio.ricaud@anahuac.mx

**Hospital Español, Ciudad de México, México. Correo electrónico: ines.hanhausen@anahuac.mx

***Instituto Nacional de Neurología y Neurocirugía, Ciudad de México, México. Correo electrónico: santiago.philibert@anahuac.mx

Perinatal palliative care emerged as an essential measure to comprehensively address the treatment of neonatal patients with prenatal or perinatal diagnoses of severe life-threatening illnesses. This care is aimed at newborns suffering from conditions that prevent them from surviving beyond a few minutes or hours, or in cases where they are born lifeless. The focus is not only on the neonatal patient, but also on supporting the mother and close relatives. The primary goal is to preserve the dignity of newborns and to provide them with the greatest possible comfort during their transition to the end of life.

Keywords: improvements in perspective; duality; cross-cutting treatment

Los cuidados paliativos perinatales surgieron como una medida esencial para abordar integralmente el tratamiento de pacientes neonatales con diagnósticos prenatales o perinatales de enfermedades graves que puedan poner en riesgo su vida. Estos cuidados están dirigidos a recién nacidos que padecen condiciones que les impiden sobrevivir más allá de unos pocos minutos u horas, o en casos en los que naces sin vida. Los mismos, no se centran solo en el paciente neonatal, sino también en apoyar a la madre y a los familiares cercanos. El objetivo primordial es preservar la dignidad de los recién nacidos y proporcionarles el mayor confort posible durante su transición hacia el final de la vida.

Palabras clave: mejoras en perspectiva; dualidad; tratamiento transversal

1. Introduction

Perinatal palliative care is defined as the care provided to pregnant women and their infants from the time of diagnosis or suspicion of a life-threatening situation. Although palliative care in adults and even older children receives much attention, perinatal care is less common and often neglected or overlooked. The purpose of this article is to explore aspects surrounding perinatal palliative care to raise awareness and sensitization of this practice. To prepare this article, articles were collected from various sources, both national and international, since, despite the recognition of palliative care, there is a paucity of research and information on perinatal care in Mexico. In addition, perinatal loss is still poorly recognized and discussed by both society and some health professionals (1).

It is crucial to consider all aspects of the people involved: the parents and the fetus. The dignity of each human being must always be respected and his or her value must be recognized from conception. Early and comprehensive planning of perinatal palliative care is essential in the face of potentially fatal diagnoses in fetuses and newborns.

2. Background

Advances in diagnostic and screening methods for prenatal diseases have opened a new window in the dimension of treatment of unborn patients. One of them being the palliative treatments that should be available in case of a fatal outcome (2).

Perinatal palliative care was born as a necessary measure to treat neonatal patients with prenatal and perinatal diagnoses of serious diseases that may endanger the life of the patient, who suffers from a condition that makes it impossible to survive more than minutes or hours; or if he/she is already born lifeless (3). This care focuses on the patient to be born but emphasizes the treatment of the mother and family.

Like adult palliative care, perinatal palliative care seeks to provide an adequate, optimal and dignified quality of life for patients with a fatal or life-threatening illness. A key differentiator in relation to adult care is the three-pronged approach of perinatal palliative care, the relationship with the patient, the mother and the relatives of the unborn child.

The first time the subject of perinatal palliative care was touched upon was in the mid-1980s, the same year in which the who incorporated the term “palliative care” and promoted it as a branch of neonatology rather than palliative care per se (4).

In an article published in 1982, Dr. William A. Silverman, a neonatologist and intensivist, comments on the potential benefit of the same treatment used in adults at the end of life; hospices where palliative care is provided but focused on neonatal patients (5).

At the beginning of the new millennium, an alternative measure was sought for all patients who did not take gestational abortion as a viable option, after a prenatal diagnosis of an incurable disease or one that was incompatible with life. It is here where the concept of merging a hospice with the neonatal intensive care units is taken up again.

Dr. Byron Calhoun of the Madigan Army Medical Center in Washington and Dr. Nathan Hoeldtke of the Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii rescued the idea and formulated an approach to the problem that they had observed in their independent units, but which both contained the same essence (6).

Having to perform comfort maneuvers for neonatal patients after the best initial measures had been taken, such as de-escalating treatments or discontinuing advanced life support measures due to their futility, physicians and staff caring for neonatal patients saw the imperative need for a physical area outside the neonatal intensive care unit.

This separate area would be just to be able to give the opportunity to perform the necessary procedures and talk to the mother and family members about the measures and steps to follow in the care of the newborn patient. Therefore, together with the social work, the medical team, the bioethics committee and a priest or religious figure, it was decided to create this annexed space where the whole team formed by the participants could work in an interdisciplinary manner.

In charge of perpetuating the dignity of the newborn patients and of offering the most comfortable way during the passage on the road to death, the assignment was validated a few years after the beginning of the 2000s; and it is still used in a similar way to this day (7).

3. Methodology

An integrative review of the literature was conducted to identify the status of perinatal palliative care. Using databases such as PubMed, Elsevier, Wiley Library, as well as Google Scholar, we searched for relevant articles.

Those considered most relevant were selected and organized according to authors and corresponding subtopics. The review included original research articles, reviews and opinions.

To complement the literature, some web pages of official sources were consulted, including current regulations.

4. Development

Pediatric palliative care prevents, identifies, and treats suffering in children with chronic, progressive, or advanced diseases and supports their families throughout the disease process (8).

Neonatal palliative care is the active and total care of the newborn with a diagnosis of life-threatening and/or life-limiting illness and his or her family from birth to 28 days of life.

On the other hand, perinatal palliative care is applied from the moment of diagnosis or from the second trimester of gestation until the first month of extrauterine life in the case of diseases that limit or threaten the life of the mother-child binomial and begins during gestation and continues during the neonatal stage.

The objective is to provide the best quality of life to the babies and their families. The aim is to eliminate or reduce the suffering caused by the disease, as well as to provide psychological and spiritual support to the patient and family members at the end of the patient’s life. Palliative care involves a multidisciplinary team of specialists and can be provided in the hospital, at home, or in hospices, if available (9).

5. Medical aspects

According to the Pan American Health Organization, 8 million newborns each year have some serious congenital defect, and approximately 40% will die before the age of five. In Latin America, congenital defects account for 21% of deaths in children under five years of age, and 20% of deaths in the first 28 days of life are due to congenital defects (10).

On the other hand, the WHO estimates that 240,000 newborns per year present congenital disorders that will cause their death in the first 28 days of life. In addition, nine out of every ten children born with severe congenital disorders live in low- and middle-income countries (11).

The Mexican Ministry of Health, in its Closing Epidemiological Report 2019, classified neural tube defects and craniofacial alterations as the most common congenital defects (12).

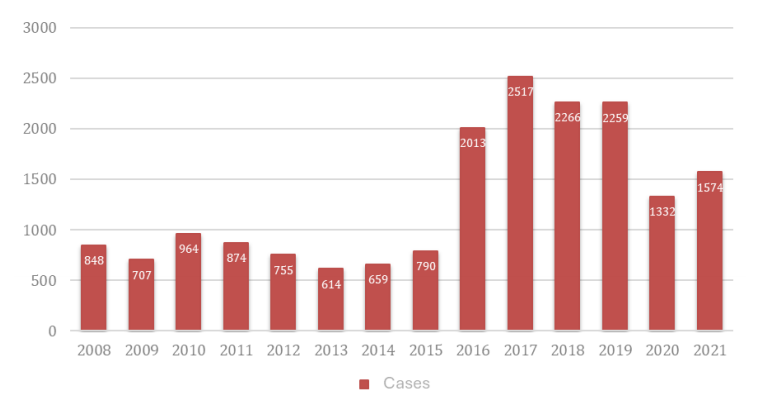

Similarly, the latest annual report available is from the year 2021, where 1574 new cases of the same defects were recorded as shown in Figure 1 (13).

Source: own elaboration, with data from: SSA/DGE/SVE DTN and DCF. Cut-off on January 08, 2021

Figure 1 Cases of congenital defects by year

Genetic syndromes and congenital malformations represent most prenatal diagnoses of disease incompatible with extrauterine life; the survival time in most of these patients is a few hours or days.

In neonates the main diagnoses related to the possibility of death in the short term are extreme prematurity, perinatal asphyxia, hypoxic or metabolic encephalopathy and very low birth weight. These patients may have a slightly longer survival, even weeks or months, in which it is important to adapt the treatments to the current conditions of the child (14).

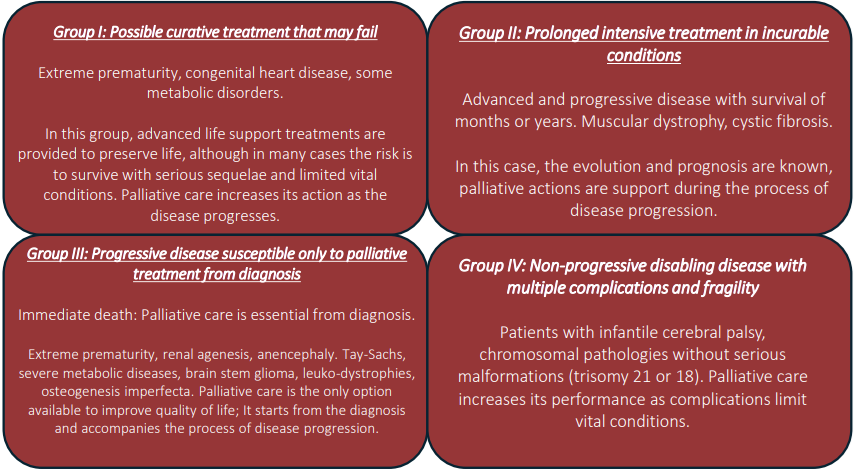

Considering Wood’s classification, the Spanish Society of Neonatology proposes the following categorization as shown in Figure 2 (15):

Source: own elaboration with data from the Spanish Society of Neonatology

Figure 2 Categorization of the Spanish Society of Neonatology

For many authors, perinatal care is a fifth group that should be added to the group of disease trajectories because of its work characteristics, even in stages as early as the first trimester of gestation.

Palliative care is indicated mainly in three situations (9):

1. When a life-threatening fetal abnormality is diagnosed before birth, and the fetus is born alive;

2. When a decision is made at the time of birth that initiation of resuscitative maneuvers is of no benefit to the baby; and

3. When neonatal intensive care is or has become futile.

In the experience reported by the team of the National Institute of Perinatology in our country, 48% die in the first hours in the toco-surgery unit, 29% die in the neonatal intensive care unit with an average survival of 8.4 days: 12% in intermediate therapy with an average stay of 10 days and 7% in minimally invasive units with an average survival of 7 days (16).

For statistical purposes in the analysis of the pediatric care guidelines, the following cases are considered for referral to palliative care: gestational age < 24 weeks of gestation, weight < 700 grams, congenital anomalies incompatible with life, children with diseases that do not respond to intensive care and who are expected to die in the short term, or children who may survive with permanent dependence on invasive life support.

Given a limited life prognosis, the possibility of applying life support technology in situations incompatible with life only prolongs the agony, reduces the quality of life, increases suffering for the patient and family, and generates a high family, moral, social, economic and health care cost.

Among the challenges for the development of neonatal palliative care in our country is the training of multidisciplinary teams with palliative training that integrate this approach from diagnosis, continuing education and training of all health professionals to facilitate detection and timely treatment. Likewise, training in bereavement and crisis intervention for health professionals; promoting self-care in the teams and providing tools for resilient coping with the adverse circumstances that arise during the perinatal stage.

6. Social aspects

This type of care is offered to families who have decided to continue with the pregnancy after receiving an end-of-life diagnosis following an ultrasound (17).

Although cases of end-of-life diagnosis should be comprehensive for the whole family, in perinatal patients’ special attention should be given because of the vulnerability of this period of development, family and patient.

Pregnancy and childbirth evoke joy and life. However, obstetrics and neonatology teams face daily the care of fetuses and newborns who will die in hours, months or years, without reaching adulthood. Although terminal patient care was initially oriented to the adult population, in the last decade there has been a growing awareness that there are children who often face the end of life without receiving adequate care (18).

In this scenario, the collaboration of the social worker is important, since he/she will describe the social context of the patient.

The family structure in which he/she lives and the relationships with non-nuclear family members. This is to structure lines of support, friendships that may be available or belonging to groups or communities.

The economic context of the patient and family members is relevant in the context in which the patient develops, the availability of resources, the characteristics of the home and the capacity to cover any extra expenses, as a secondary product of a medical emergency or a very prolonged treatment.

When speaking of palliative care, the concept of quality of life must be considered, which will be understood as the state of general satisfaction, in terms of the feeling of material and personal well-being, such as health, education, functionality, housing, social security, and subjectively the feeling of physical, psychological and social well-being; such as the expression of emotions and the sense of belonging to social groups, establishing harmonious relationships with oneself, with the environment and with the community when carrying out daily activities (19).

To refer to the quality of life of a patient we must consider the presence of symptoms such as pain in the patient and emotional aspects such as anxiety and depression (20).

Palliative care, being integral, must attend to the patient’s quality of life, as well as that of the family members, in the case of perinatal care, paying special attention to the parents who are in great vulnerability.

In Mexico, attention has been paid to palliative care since 2009, the year in which the institutionalization and development of academic work began, at the same time as the reforms to the General Health Law (21). Although this is a step forward, the specific field of perinatal care is still a little explored area.

It is important to consider cultural aspects, such as the customs and beliefs of the patient’s nuclear family, as well as how they want to deal with the treatment and the corresponding mourning.

This type of social structure is directly related to the accumulation of spiritual beliefs, which will be addressed below.

7. Spiritual aspects

The spiritual value is focused more on those who remain in this life, i.e., the mother and the relatives of the neonatal patients.

The aim of this approach is to find out how the parents see life and what might be the best approach to the ultimate meaning of life.

Beliefs, values, traditions and rituals create a support network that supplements decision making and nurtures the relationship that must be established with the palliative care team to face the subsequent stages in the dying process.

This basis will support how they live -or coexist- with the disease, the choices regarding treatments or measures, the experience of pain, the dying process and ultimately the bereavement process (15).

Not only is it a tool for the benefit of the patient at certain times, but it also helps to prevent and support feelings of hopelessness and anxiety that may require intervention from outside the medical team. Depending on their beliefs, parents may seek the guidance of a chaplain, pastor or rabbi; even a shaman or similar figure who can provide spiritual peace (22).

At the same time, consideration should be given to the rituals that family members may request, depending on their customs and traditions. To facilitate effective and complete treatment, these should be validated, regardless of the position that the palliative care team may have in this regard, since at this time only accompaniment and compassion are sought and offered.

These same rituals or conceptions of death are the way in which parents and relatives express their love for patients who have just been born and are already on the road to death. They are doors that open a level of wholeness and well-being within the storm of suffering they are experiencing. By giving the neonatal patient, a place in the community, it allows family members to catharsis after recognizing that this individual, although no longer in this life, will always remain part of the community (23).

The forms of spiritual accompaniment are even more varied than one might think, since it is not only in the religious sense, but the search for connection between the souls -family, patient and palliative team- can be given in different ways that go beyond the religious sense.

An example of this is the use of music therapy as a method of out-of-hospital emotional support for patients and families (24).

Another example is the possibility of interaction between the patient and his older siblings -if any-. This experience brings peace to the siblings by allowing them to establish a real connection with the patient, albeit fleeting and fleeting, and thus to have a more satisfactory outcome (25).

The aspects that should be touched on and supported in the spiritual sphere of patients, mothers and family members are even deeper than religiosity itself. Of course, it is true that religious beliefs are a fundamental part of how the world is conceived, and therefore how one will act accordingly. However, the spirit transcends beyond the resonance of the patient’s religion with that of the team.

The true spiritual accompaniment is the capacity granted by the interconnection of the souls of both the team and those receiving palliative care to experience together the reality that is being lived; and to provide the necessary arsenal so that those who remain in this life can leave the ordeal and continue living with the learning that this extreme situation has allowed.

8. Practical aspects

Access to termination of pregnancy and the gestational limit from which it can be applied are the subject of professional, political, legal and public debate. Legislation in Mexico includes palliative care from the perinatal period and throughout the lifeline (8).

When parents decide to continue with a pregnancy with a probable fatal outcome for the fetus, careful planning of perinatal palliative care is required. There is evidence that this option can reduce the possible emotional and psychological effects associated with the other option-abortion (26).

In a prospective multicenter study in France, where abortion is legal for life-threatening diseases for the fetus, 19% of women with these diagnoses decided to continue with their pregnancy. Of these, a palliative care plan was made for only 10% (27). Planning a birth in these cases goes beyond the traditional, but also involves the prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal stages. Post-diagnostic advance directive planning helps parents to have a feeling of greater control in coping with their child’s condition. In this way they can make known their beliefs, requests, goals for the remainder of the pregnancy and the infant’s lifespan (2).

By starting perinatal palliative care with a multidisciplinary team, there is continuity of care with the baby and parents, which helps reduce the social and medical isolation to which family members are potentially exposed and allows them to decide how they can make the most of every second with their child (1).

In 2021, Crawford and colleagues published a descriptive study evidencing the feelings of women with perinatal palliative care. These experiences are valuable because they help us to put in place more practical methods for patient care. The relevance of having commemorative objects of the pregnancy and the child is highlighted, since they represent a tangible memory. The empathy of all the professionals involved in the process is also important, as well as the support groups, since they provide the parents with a sense of accompaniment and belonging (28).

In view of the above, it is concluded that early planning of perinatal palliative care is important, which offers comfort to both the baby and the family and is a means to alleviate physical and emotional suffering. The option should always be offered to parents with children with actual or potentially fatal disorders.

9. Bioethical considerations

Palliative care is generally recognized as an instrument of recognition of the dignity of the person at the end of life. This is widely seen and heard in cases of palliative care in children and adults. However, in the perinatal stage, the highest virtues of palliative care come to the fore.

First, dignity is recognized regardless of condition. Despite not having active decision-making capacity, their autonomy is respected through that of the parents. Even though fetuses or newborns have genetically and/or phenotypically abnormal or different traits, they are recognized as the human beings they are. And, although they have a fleeting life span, love, affection and above all respect are maximized in every precious moment. In fact, it has been reported that parents have greater ease and adaptability in the face of grief by recognizing their baby’s status as a “person” and his or her role in the family (29).

Second, human life is recognized from conception as a life that will soon end. Plans for the short extrauterine life are initiated, including the organization of farewell rituals. By reaffirming the humanity of the product of gestation, its well-being is always sought, and it is always treated with respect. In this sense, perinatal palliative care is seen as an alternative to abortion of products of pregnancy with poor prognosis, mirroring the alternative of euthanasia in adults (30).

Moreover, although the fetus or newborn cannot decide for itself, its autonomy is respected through that of the parents, who look after its greater good. This is something very particular to perinatal palliative care, since it extends directly to the mother (and often to the father) as participants and focus of the care provided.

It is clear here the integrality of Bioethics, in which nothing can go unnoticed, every detail is important. Every life is important. The socio-cultural context of the parents, medical prognoses, mental health, the wellbeing of the newborn, future memories, the search for meaning, transcendence, and legality all play a role in the decision to opt for palliative care and to carry it out appropriately.

10. Discussion

Perinatal and postnatal (intrapartum and postpartum) palliative care is a watershed in the quality of life that can be provided to newborn patients who are dying, and to mothers and families who are grieving the loss of a newborn.

By recognizing the duality of the human being, physical substance and spiritual essence from before birth, it allows us to face in an integral way the difficult situation of the outcome of a relationship that is just blossoming. This being that of the newborn with his family and society. Secondary to the fact that value is given to the substance and, therefore, to the physical pain that the parties may experience, palliative care has an expeditious impact.

First, the care provided to the neonate is focused on providing a light and painless transit through this life, during the short time he/she is in it. From comfort measures, such as hydration and analgesia, to more exhaustive procedures such as sedation and ventilatory assistance. The purpose of this first instance is to perform the necessary maneuvers so that the patient does not suffer in the transition from the beginning of extrauterine life to this life.

Secondly, there is the care of the physical pain of the mother and family members. When a diagnosis is made, often prenatally, the suffering it generates is of a rather psycho-spiritual nature. But equally, in situations of complicated births, the physical pain of the mother can play against the total control of the neonatal patient’s pain, which is why bipartite control is a fundamental cornerstone to be addressed, first of all.

On the other hand, attention to the psycho-spiritual sphere through the accompaniment of family members is another fundamental pillar in the full treatment of these situations.

The various authors report that it is necessary to know the preferences, beliefs, customs and attitudes that the parents or relatives have, to be able to provide close assistance, with a vision focused on the patient and for the patient (31).

This vision, in addition to clarifying the panorama regarding joint decision making, favors the work of the different stages of the process of death and mourning, since the latter is carried out in different ways depending on the beliefs of each specific family or community.

Given the intrinsic difficulty that exists in the integral treatment of patients and family members, resulting from the complex consonance of the perennial biopsychosocial-spiritual spheres of the human being, palliative care in the perinatal setting is presented as a link that allows reunifying these spheres. By giving family members, the possibility of contemplating the beneficial transition of the neonatal patient through palliative care, the restructuring during and after the outcome becomes relatively easier, because the accompaniment was carried from the beginning of the situation; committed to the worldview of those who weigh them and focused on individualized treatment.

Not only is symptom control a key factor in palliative treatment, but in these specific cases, spiritual accompaniment becomes fundamental. When facing the beginning and end of life in an instant -and under situations that are out of the ordinary- the value centered on the person comes to the fore; and due to the different spheres, that make up the same, the integral treatment of patients falls not only on the medical team, but also on those who offer psychological and spiritual comfort (32).

Unfortunately, a limiting factor for the optimal and integral treatment of patients and family members is the discordance that usually occurs when two different worldviews are confronted: that of the team and that of the family members or patients.

These obstacles, instead of slowing down and generating doubt as to whether the path taken is the right one, function as a possibility to act and inform about the need to avoid frictions arising from conceptions or ways of seeing life and death in different ways. Rather, they allow to emphasize the need to validate preferences so that they can be managed by all parties.

11. Conclusion

Perinatal care should include a palliative vision for those cases that represent the greatest vital risk; it is essential to assess the clinical situation accurately, recognize the risks of possible courses of action and establish plans of action agreed upon with the parents that provide the greatest well-being for the neonate and his or her family.

Prognostic uncertainty in many cases represents the greatest challenge for effective advance planning, empathetic communication, dedication and patience to clarify possible courses of action in the face of unfavorable disease progression.

Let us remember that parents are at the same time caregivers and legal agents of guardianship and decision making in favor of the newborn, which generates complex situations within the same family. It is also convenient to have spiritual support that facilitates reaching agreements for the best welfare of the child.

It is very important to allow the interaction of the parents to generate bonds and loving memories, to favor that the death occurs in a comfortable environment and to facilitate the processes of farewell according to the family needs and the sociocultural constructs of each case.

The deliberative process is undoubtedly an excellent option for resolving conflicts and facilitating acceptable and quality advance planning for all involved, including care and stress reduction for the health care team itself.

Referencias

1. Sumner LH, Kavanaugh K, Moro T. Extending palliative care into pregnancy and the immediate newborn period: state of the practice of perinatal palliative care. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs [Internet]. 2006; 20(1):113-6. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005237-200601000-00032 [ Links ]

2. Cortezzo DE, Ellis K, Schlegel A. Perinatal palliative care birth planning as advance care planning. Front Pediatr [Internet]. 2020; 8. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.00556 [ Links ]

3. Crawford A, Hopkin A, Rindler M, Johnson E, Clark L, Rothwell E. Women’s experiences with palliative care during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs [Internet]. 2021; 50(4):402-11. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2021.02.009 [ Links ]

4. Del Rio I, Palma A. Cuidados paliativos historia y desarrollo. 2007. https://cuidadospaliativos.org/uploads/2013/10/historia%20de%20CP.pdf [ Links ]

5. Carter BS. An ethical rationale for perinatal palliative care. Semin Perinatol [Internet]. 2022; 46(3):151526. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151526 [ Links ]

6. Hoeldtke NJ, Calhoun BC. Perinatal hospice. Am J Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2001; 185(3):525-9. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mob.2001.116093 [ Links ]

7. Kain VJ, Chin SD. Conceptually redefining neonatal palliative care. Adv Neonatal Care [Internet]. 2020; 20(3):187-95. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000731 [ Links ]

8. Narro JR, Ancer J, García-Moreno J. Guía del Manejo Integral de Cuidados Paliativo. 2018; Disponible en: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5534718&fecha=14/08/2018#gsc.tab=0 [ Links ]

9. Winyard A. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics Report - Critical care decisions in fetal and neonatal medicine: Ethical issues. Clin Risk [Internet]. 2007; 13(2):70-3. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/135626220701300208 [ Links ]

10. Panamerican Health Organization (PAHO). Nacidos con defectos congénitos: historias de niños, padres y profesionales de la salud que brindan cuidados de por vida [Internet]. Paho.org. [citado 27 de noviembre de 2022]. Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/3-3-2020-nacidos-con-defectos-congenitos-historias-ninos-padres-profesionales-salud-que [ Links ]

11. Panamerican Health Organization (PAHO). Defectos congénitos. La importancia de un diagnóstico temprano [Internet]. Paho.org. [citado 27 de noviembre de 2022]. Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/3-3-2023-defectos-congenitos-importancia-diagnostico-temprano [ Links ]

12. Zaldivar A. Informe Epidemiológico de Cierre 2019. Ciudad de México; 2019. Disponible en: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/541110/InformeDMT21erTrim2019.pdf [ Links ]

13. Zaldivar A. Informe de Vigilancia Epidemiológica 2021. Ciudad de México; 2021. Disponible en: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/745354/PanoEpi_ENT_Cierre2021.pdf [ Links ]

14. Wood F, Simpson S, Barnes E, Hain R. Disease trajectories and ACT/RCPCH categories in paediatric palliative care. Palliat Med [Internet]. 2010; 24(8):796-806. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0269216310376555 [ Links ]

15. Martín-Ancel A, Pérez-Muñuzuri A, González-Pacheco N, Boix H, Espinosa Fernández MG, Sánchez-Redondo MD, et al. Perinatal palliative care. An Pediatr (Engl Ed) [Internet]. 2022; 96(1):60.e1-60.e7. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anpede.2021.10.003 [ Links ]

16. Instituto Belisario Domínguez. Mi cuidado, Mi derecho. Cuidados Paliativos Pediátricos. Ciudad de México: Senado de la República; 2021. [ Links ]

17. Comas Ferrer C. Cuidados paliativos perinatales: mejorar el afrontamiento y el duelo de las familias que pierden a un neonato con un diagnóstico fetal limitante. [Internet]. 2022 [citado 27 de noviembre de 2022]. Disponible en: http://dspace.uib.es/xmlui/handle/11201/157786 [ Links ]

18. Martín-Ancel A, Mazarico E. Afrontar el final de la vida cuando la vida empieza: cuidados paliativos perinatales. Rev iberoam bioét [Internet]. 2022; (18):01-14. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.14422/rib.i18.y2022.001 [ Links ]

19. Teefey CP, Hertzog J, Morris ED, Moldenhauer JS, Cole JCM. The impact of our images: psychological implications in expectant parents after a prenatal diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol 2020; 50:202833. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-020-04765-3 [ Links ]

20. González C, Méndez J, Romero JI, Bustamante J, Castro R, Jiménez M. Cuidados paliativos en México. Rev Med Hosp Gen Méx. 2012; 75. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359861521_Cuidados_Paliativos_en_Mexico [ Links ]

21. Santos ZT-DL, Rodríguez FP-, Corona T. Investigación sobre Cuidados Paliativos en México. Revisión Sistemática Exploratoria [Internet]. Medigraphic.com. [cited 2024 Apr 02]. Disponible en: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/revmexneu/rmn-2018/rmn182h.pdf [ Links ]

22. Kain VJ. Perinatal Palliative Care: Cultural, Spiritual, and Religious Considerations for Parents. What Clinicians Need to Know. Front Pediatr 2021; 9. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.597519 [ Links ]

23. Garten L, Globisch M, von der Hude K, Jäkel K, Knochel K, Krones T. Palliative care and grief counseling in Peri- and neonatology: Recommendations from the German PaluTiN group. Front Pediatr [Internet]. 2020; 8:67. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.00067 [ Links ]

24. Engelder S, Davies K, Zeilinger T, Rutledge D. A model program for perinatal palliative services. Adv Neonatal Care [Internet]. 2012; 12(1):28-36. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0b013e318244031c [ Links ]

25. Ziegler TR, Kuebelbeck A. Close to home: Perinatal palliative care in a community hospital. Adv Neonatal Care [Internet]. 2020; 20(3):196-203. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000732 [ Links ]

26. Kilby MD, Pretlove SJ, Bedford Russell AR. Multidisciplinary palliative care in unborn and newborn babies. BMJ [Internet]. 2011 [citado 6 de abril de 2024]; 342(apr11 1):d1808-d1808. Disponible en: https://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.d1808 [ Links ]

27. de Barbeyrac C, Roth P, Noël C, Anselem O, Gaudin A, Roumegoux C. The role of perinatal palliative care following prenatal diagnosis of major, incurable fetal anomalies: a multicentre prospective cohort study. BJOG [Internet]. 2022; 129(5):752-9. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16976 [ Links ]

28. Côté-Arsenault D, Denney-Koelsch E. “My baby is a person”: parents’ experiences with life-threatening fetal diagnosis. J Palliat Med [Internet]. 2011; 14(12):1302-8. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2011.0165 [ Links ]

29. Kuebelbeck A. “Yes to Life” and the Expansion of Perinatal Hospice. Perspect Biol Med 2020; 63:526-31. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2020.0041 [ Links ]

30. Cobb AD. Christian Humility and the Goods of Perinatal Hospice. Christian Bioethics: Non-Ecumenical Studies in Medical Morality. 2021; 27:69-83. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1093/cb/cbaa017 [ Links ]

31. Tewani KG, Jayagobi PA, Chandran S, Anand AJ, Thia EWH, Bhatia A. Perinatal Palliative Care Service: Developing a Comprehensive Care Package for Vulnerable Babies with Life Limiting Fetal Conditions. J Palliat Care 2021; 37:471-5. https://doi.org/10.1177/08258597211046735 [ Links ]

32. Veldhuijzen van Zanten S, Ferretti E, MacLean G, Daboval T, Lauzon L, Reuvers E. Medications to manage infant pain, distress and end-of-life symptoms in the immediate postpartum period. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2022; 23:43-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2021.1965574 [ Links ]

Received: January 05, 2024; Accepted: April 23, 2024

texto en

texto en