1. Introduction

Environmental and energy problems worldwide have forced researchers to seek sustainable energy solutions. They have found renewable alternatives such as wind, sun, and water to generate clean and environmentally friendly energy (Djørup et al., 2018; Erdiwansyah et al., 2019; Hansen et al., 2019; Nicolli & Vona, 2019). The energy available from water resources is the world’s largest and cheapest (Yuce & Muratoglu, 2015). Large hydroelectric dams have been criticized because they require large dams and infrastructure that cause damage to the environment and ecosystems (Hoq et al., 2011). Accordingly, small hydroelectric plants have become one of the most economical and environmentally friendly sources of energy generation in rural areas (Woodruff, 2007). There are two techniques to extract energy from water: hydrostatic and hydrokinetic. Hydrostatic techniques use turbomachinery to extract the potential energy from the pressure head (Khan et al., 2008). Hydrokinetic techniques (HKTs) use the kinetic energy of channels, tides, oceans, and rivers along with turbo machinery to generate energy. Diverse numerical and experimental research has been conducted worldwide regarding HKTs, with the purpose of improving the performance of different rotors (Goundar & Ahmed, 2013; Wang et al., 2019). Table 1 summarizes the most recent results.

Table 1 Recent state of the art.

| Reference | Type | Foil | V [m s-1] | D [m] | TSR | Cp |

| (Gupta & Subbarao, 2020) | Num | SG6043 | 2 | 1,2 | 5 | 0,51 |

| (Gish et al., 2020) | Exp | NACA4412 | 0,91-1,52 | 0,265 | 4 | 0,33 |

| (Abutunis et al., 2020) | Exp | Eppler 395 | 0,98 | 0,109 | 5 | 0,27 |

| (Nachtane et al., 2020) | Num | NTS-XX20 | 2 | - | 6,5 | 0,51 |

| (Kirke, 2020) | Rev | - | - | - | - | - |

| (Fontaine et al., 2020) | Exp | MHKF1 | 2-7 | 0,574 | 4,5 | 0,45 |

| (Shahsavarifard & Bibeau, 2020) | Exp | H0127 wind | 1,1 | 0,198 | 4 | 0,4 |

| (Hazim et al., 2020) | Num | NACA63421 | 1,25 | 10 | 5,23 | 0,33 |

| (Lust et al., 2020) | Exp | NACA63618 | 1,68 | 0,8 | 7 | - |

| (Nunes et al., 2020) | Rev | - | - | - | - | - |

| (Wood et al., 2021) | Num | NACA63618 | 2,5 | 10 | 7,33 | - |

| (Okulov et al., 2021) | Exp | SD7003 | 0,6 | 0,376 | 5 | 0,4 |

| (Sandoval et al., 2021) | Num | Goettingen804 | 0,45 | 0,27 | 4,5 | - |

| (Aguilar et al., 2021) | Num-Exp | Eppler 420 | 1,5 | 1,58 | 6,74 | 0,42 |

| (Lazzerini et al., 2022) | Num Exp | Eppler 818 | 1,2-1,8 | 0,42 | 3 | 0,35 |

| (Wang, et al., 2022) | Num | - | 2 | 1 | 4 | - |

| (Puertas-Frías et al., 2022) | Rev | - | - | - | - | - |

| (Alipour et al., 2022) | Num-Exp | NACA63618

NACA25112 NACA44xx NACA24xx |

1 | 0,5 | 7

7 7 7 |

0,33

0,36 0,5 0,47 |

| Actual | Num

Exp |

Eppler 817 | 1,4

1,36 |

0,5

0,25 |

4

4 |

0,434

0,267 |

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software is widely used to simulate the behavior of fluids such as water and air, given that they represent an economical way of obtaining results close to reality. For this reason, many authors have used CFD software to solve physical phenomena (Betancur et al., 2019; Esfahanian et al., 2013; Sufian et al., 2017). Tian et al. (2018) performed three-dimensional simulations of a hydrokinetic turbine with three blades. They used the shear stress transport k-ω SST turbulence model. The numerical results were compared to experimental ones. In a study by Lee et al. (2012), a three-dimensional simulation with the blades of a hydrokinetic turbine was conducted. As a result, power coefficient vs. TSR curves were obtained and compared with experimental and other numerical results. Pujol et al. (2015) conducted a study on the geometry of the water wheel to improve its efficiency. The results of the simulation were reported with uncertainty using the grid convergence index (GCI), and they were finally compared to experimental results.

Few articles have reported the numerical uncertainty of three-dimensional simulations; it is a complex task due to the sensitivity of the performance variables and the high computational cost. One of the techniques used to determine numerical uncertainty by means of systematic refinement is the GCI (Karaalioglu & Bal, 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Mohamed et al., 2020; Paudel & Saenger, 2017; Pujol et al., 2015; Roy & Blottner, 2006). GCI is based on Richardson’s extrapolation theory, which is used for discrete solutions with different grid densities (Roache, 1998). In this work, we managed to quantify the numerical uncertainty of a three-dimensional CFD simulation for a horizontal-axis hydrokinetic turbine. Three grids with different element densities were used to calculate the uncertainty of the numerical results. Torque (τ) was the output variable used to quantify numerical uncertainty.

Thereupon, this article is structured as follows. The first section shows the way in which the CFD simulation was configured. Then, the calculation of the numerical uncertainty is presented. Next, the physical model and the experiment are described. In the following section, the results of the simulation are presented, where the obtained behavior of the fluid near the turbine is compared with other similar studies. Moreover, the GCI results and the performance graph of the turbine, along with its corresponding numerical uncertainty, are presented. Then, the experimental and numerical results are compared. Finally, a discussion about the results is proposed, and the conclusions are presented.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. CFD simulation

For the three-dimensional simulation, the CFX® module of ANSYS® was used. To elaborate the grid, an HP Workstation Z600 with a 2,66 GHz processor, 48 GB of RAM, and 12 processing cores was used. For the simulations, a DELL T7600 Workstation with a 2,9 GHz processor and 32 GB of RAM was employed, as well as 12 cores in parallel for a double precision solution. For this study, the geometry of a rotor was imported, which was built with the EPPLER 817 hydrofoil in previous research (Betancur et al., 2020) through BEM (Blade Element Methodology) modeling. Moreover, the k-ω SST turbulence model was used, given its wide use in research regarding hydrokinetic turbine applications, as well as the accuracy it offers due to the treatment near the geometry walls, where the grid was densified to ensure the y+ recommended for the model of 0,02 (Tian et al., 2018).

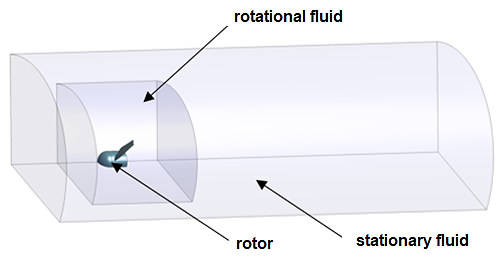

Once the solid model of the turbine was imported, Boolean operations were performed to create two different fluids. The first is a rotating fluid that contains the rotor and is built from a circle with a 1 D radius (Jeffcoate et al., 2016) and a height of 1 1/3 D, where D is a rotor diameter equal a 0,5 m. The second is a stationary fluid containing the first, which enters freely and contrary to the axis. This control volume has a total length of 5 1/2 D and a radius of 2 1/2 D (Kim et al., 2017). In Figure 1, the two control volumes and the turbine rotor can be observed. Since it is a symmetrical geometry that repeats itself three times, a third of the total volume is simulated to save computation times. This simplification does not affect the results according to (Lee et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014). The design methodology in the discussion on details regarding the solver configuration can be consulted in previous research (Betancur et al., 2020), the rotor has a diameter of 0,5 m, 3 equidistant blades, with a maximum chord of 0,0957 m and a minimum of 0,0404 m, and a warpage of 42,3° at the base and 5,85° at the tip.

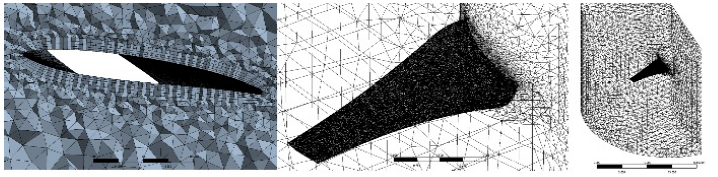

A grid was built in the control volumes of the exterior fluid and the one surrounding the rotor. The grid was elaborated on the Meshing® module of ANSYS®. An inflation with five layers around the blade was used, as shown in Figure 2a. This area was densified (see Figure 2b) since it is where the phenomenology of interest takes place. The mesh of this fluid (Figure 2c) is composed of hexahedra surrounding the blade and tetrahedra in the rest of the volume. Then, the minimum element measurement was parameterized to densify the mesh in a structured way and generate other two. Table 2 presents the details and the main metrics of the three meshes created. The accepted range for orthogonal quality is 0,15-1. The acceptability range for the maximum skewness is between 0 and 0,94, and the aspect ratio must be lower than 30 (ANSYS, 2010). As can be observed, all metrics of each mesh comply with the acceptability ranges.

Figure 2 a) Inflation around the blade, b) element density in the blade, c) rotational control volume.

Table 2 Mesh details and metrics.

| Mesh | No. of

elements |

Max.

Skewness |

Min.

Orthogonal Q. |

Aspect

Ratio |

| Fine | 1,03E+07 | 0,677 | 0,152 | 10,92 |

| Medium | 1,35E+06 | 0,786 | 0,214 | 7,98 |

| Low | 7,94E+05 | 0,797 | 0,203 | 8,49 |

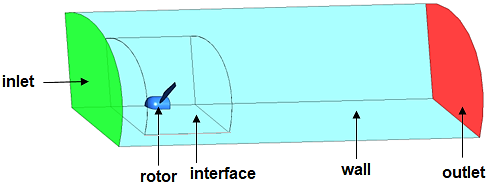

Figure 3 shows the borders defining the regions of the fluids to be simulated and the boundary conditions of the control volume. Symmetry interfaces were defined in the flat faces of the control volume to indicate that the phenomenology is repeated in the next section. The values with which each of the regions were configured are reported in Table 3, namely normal velocity on entry, relative pressure on exit of 0 Pa, no-slip condition on the wall rotor, and periodic rotational condition in the symmetry interfaces established between the two fluid volumes defined above.

Table 3 Boundary conditions of the study.

| Condition | Value |

| Type of fluid | Water at 25°C |

| Turbulence model | SST |

| Inlet velocity | 1,4 m s-1 |

A transitory 4s simulation was configured with an adaptive time-stepping varying between 0,01 s and 0,00001 s. This time stepping was established using the Courant number equation, for which the smallest mesh element size was used, as well as the lowest fluid velocity on the blade’s surface, which is the point where these mesh elements appear. The outer domain is considered stationary, and the fluid surrounding the rotor is configured to rotate between 1 to 385 rpm. The frameshift was configured as “Frozen rotor,” and the interface model was of general connection, whereas, for the periodical interfaces, the interface model was periodical-rotational. When the configuration was done, the torque on the blade surface was selected as the monitoring variable. Furthermore, a high-resolution was used for the advection scheme, the second-order Backward Euler equation, a 1E-4 convergence criterion, and double precision.

2.2. Quantification of numerical uncertain

Given the increase in research on CFD, studies have been conducted which aim to improve the quality of the results. For this reason, some authors have proposed new practices that contemplate numerical uncertainty, which had not been considered thus far (Celik, 1993). Numerical uncertainty is due to the errors involved in the numerical modeling of the Navier-Stokes equations and includes the influence of discretization errors, rounding error, and iterative convergence (Eça & Hoekstra, 2009; Freitas, 2002; Roy, 2005). Moreover, it cannot be eliminated, but it must be minimized and quantified (Freitas, 2002), so it is recommended to use the GCI to calculate it and therefore determine a simulation’s level of accuracy (Freitas, 2002).

To calculate the GCI, the representative cell or grid size h is first defined. Three-dimensional calculations are performed with the Equation (1).

Where

Then, three grids must be selected: a fine one (m

1

), a medium one (m

2

), and a course one (m

3

). Once the key or significant variable (φ) is obtained, the refinement factor (r) is calculated, so that

Where

The convergence condition (R) is evaluated with the Equation (4).

The possible results of Equation (4) are:

If 0 < R < 1, monotonous convergence.

If R < 0, oscillatory convergence.

If R > 1, divergence.

Roache (1994) combines the concept of safety factor with absolute values to generate the error bar instead of the estimation of the error. As a result, the numerical uncertainty is obtained, which is also known as the grid convergence index (GCI) and is calculated with the Equation (5).

Where

2.3. Experimental setup

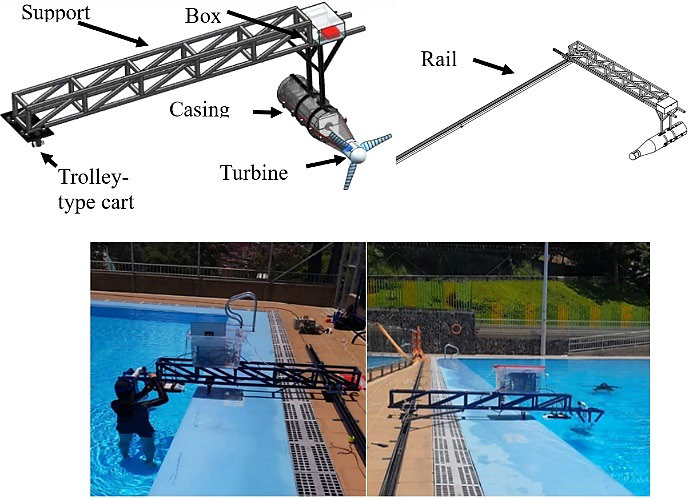

The physical model consists of a system comprising a mobile support, a casing, a turbine, and an instrument box that are attached to a trolley type cart that moves guided within a fixed rail, as seen in Figure 4.

This system can be moved at different velocities since it has a frequency driver that controls a 1 HP motor, which has a pulley on its axis with a steel wire. One end of the wire is fixed to the mobile support, which allows it to move along a 21 m rail located at the edge of a semi-Olympic swimming pool. The casing and turbine systems are submerged at a depth of 0,8 m, 1 m from the wall, and 0,7 m from the bottom. The rotor used for this experiment is the same as that was used in the simulation, but at a scale of 1:2. Inside the bearing, there is a sensor that allows measuring the torque and the angular velocity in the turbine. It has a motor that serves as a brake and flexible coupling to complete the installation. The rotary torque sensor is a FUTEK® of up to 50 Nm. It provides measurements with a precision of 0,2%, and it has a 0,1% hysteresis and a 0,2% unrepeatability, as well as a certified factory calibration under the ISO 17025 norm.

As an input variable, the flow velocity of the test stand was evaluated with a velocity of around 1,4 m s-1. The velocity at which the system moves has the same magnitude as the velocity of the water

The revolutions per minute were monitored with the DC motor’s voltage, which was varied from 0 to 3,8 V to achieve constant rotational speeds. The system was stabilized three seconds after startup, and during the following nine seconds, the first and second output variables were obtained, namely the turbine’s revolutions per minute and the torque.

To elaborate the rotor's operation curve, it needs to be evaluated for TSR between 1 and 6 while varying the voltage. The values of the second output variable were multiplied by the rotation speed in RPM. This term, divided by the hydraulic power, results in the rotor’s power coefficient or performance. With these data, the characteristic curve of Cp vs. TSR is elaborated for each rotor.

Noise factors or error causes were also identified, such as weather or environmental conditions at the testing site, namely stirring or resting states in the pool’s water, deformation and/or vibrations suffered by the test stand, rotor roughness, braking in the bearings supporting the turbine axis, and others.

The data obtained with the sensor were exported to a spreadsheet, and, for each observation, the following procedure was conducted: the RPM data were filtered, and between 50 and 100 values were obtained for each value; the RPM were associated with a TSR by means of Equation (6); the average of the torque values associated with this TSR was found; and the standard deviation was calculated with Equation (7).

Where

Where

The torque values (T) and RPM are taken to Equation (9) to calculate the power coefficient.

Where

Where

3. Results and discussion

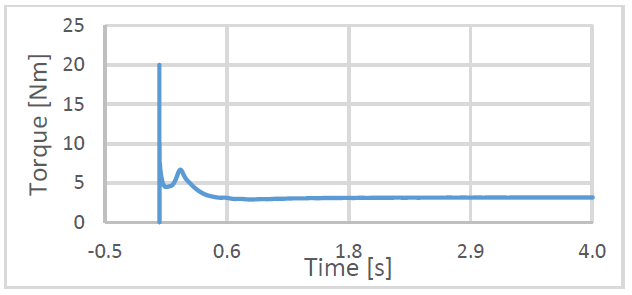

Figure 5 shows a curve corresponding to the behavior of the observation variable (torque) in a transitory 4s simulation for the finest mesh. It can be evidenced that, initially, the torque shows an irregular behavior, where it reaches its maximum and minimum points. After the first second, the torque starts to stabilize and manages to remain constant from second 3 until the end. The same behavior was evidenced for grids 1 and 2.

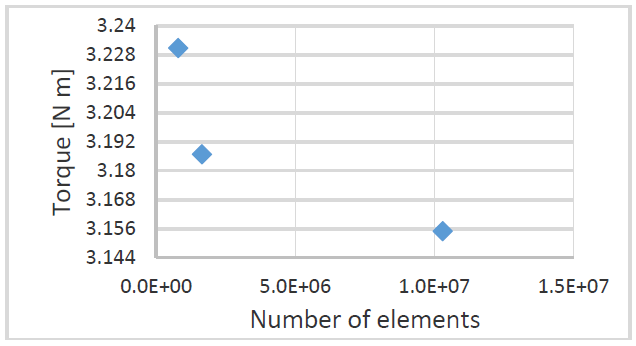

Figure 6 shows three points that represent the torque behavior as the mesh densifies. The first point at the beginning of the graph for 7,94E5 elements with a torque of 3,23084 Nm. The second point is with 1,65E6 elements and a torque of 3,18678 Nm and the last point with the finest mesh of 1,03E7 elements and a torque of 3,15496 Nm. As the number of elements increases, the torque decreases. This is because the finer meshes contain more elements, therefore they capture the studied phenomenon with greater precision.

GCI is calculated using torque as the main variable. As the value of R is 0,722, and it is between 0 and 1, it is said that the convergence condition for the torque is monotonous. Furthermore, the GCI was calculated for grid 1 (GCI12) and 2 (GCI23) with a safety factor of 1,25, thus obtaining values of 0,203 and 1,449, respectively. The results show that, as the grid becomes denser, the error decreases. For this razon the finest grid was chosen to continue with the second part of the investigation.

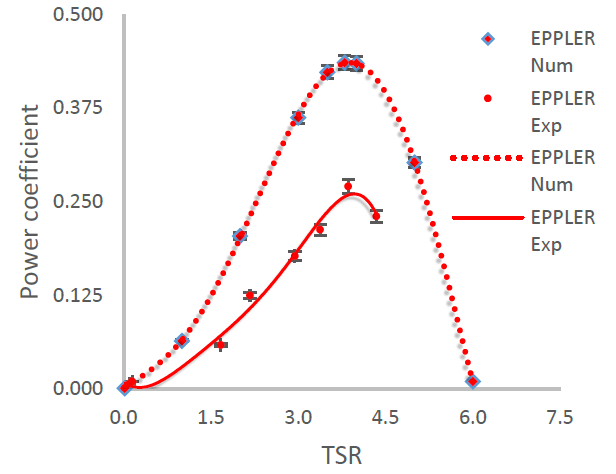

For this study, the TSR was varied only between 0,1 and 6, to obtain torque values at different TSR, and the power coefficient was calculated by means of Equation (6). In Figure 7, the performance curve of the simulated rotor is shown, as well as the numerical uncertainty calculated with the GCI. It can be evidenced that, as the TSR increases, the power coefficient does as well, up to TSR=4, where it starts to decrease. On the other hand, the error bar varies proportionately to the power coefficient. Figure 7 shows the curves of the power coefficient versus TSR elaborated from the experimental and numerical results. The behavior of the experimental and simulation curves is similar; the Cp values increase as the TSR increases, and, when a TSR between 3 and 4 is achieved, the Cp reaches its maximum point and starts to decrease. For TSR higher than 4,5, high RPM are required, and given the distance limitations of the test stand, these speeds could not be achieved. Therefore, the results obtained in the experimental curves only get to that point. The experimental uncertainty calculated with Equation (10) was 0,0057 the lowest for TSR 1,67 and 0,054 the highest for TSR 3,86.

Experimental and numerical maximum Cp difference was 38,48%. The difference between the numerical and experimental results is due to several factors. The first of them is the mechanical loss occurring in the hermetic casing given the packing used to provide the axis inlet with tightness. Although the couplings are high efficiency, there are critical areas such as the seal, where there may be losses due to friction with the axis. Another factor that causes the difference between the numerical and experimental results to be high is the control over the test stand’s speed. The average velocity data for the test stand was 1,36 m s-1, with a standard mean deviation of 0,06. This value is because the rails on which the cart moves are irregular, which causes mild braking in some segments, slight jamming, and other types of phenomena which are difficult to control. The fluid velocity increase and decrease considerably affect the power coefficient value (Lin et al., 2017).

The greatest contribution of this work is the experimental validation of numerical results. As can be seen in Table 1, few studies conduct this validation. Numerical studies simulate turbines between 1 and 10 m. Only Sandoval et al. (2021) and Lazzerini et al. (2022) numerically study turbines smaller than 0,27 and 0,42 m, respectively. While the experimental studies evaluate turbines on a scale between 0,109 and 0,8 m. Only Lazzerini et al. (2022) simulated the rotor to be the same size as the scale model they experimented with. They used a hydrofoil like the one in the presented study and obtained a Cp consistent with the results reported here. Table 1 shows that the Eppler hydrofoil family is of great research interest and that the Cp found varies between 0,27 and 0,42. This is supported by the results of this work, whose experimental finding coincides with Abutunis et al. (2020), while the numerical one agrees with Aguilar et al. (2021). Finally, it is highlighted that the numerical Cp between 0,33 and 0,51 are higher than the experimental ones between 0,27 and 0,45, this study being conclusive as to the cause of the difference.

4. Conclusions

A horizontal-axis hydrokinetic turbine rotor designed with the EPPLER E817 hydro profile was numerically and experimentally evaluated. The power generated according to the maximum power coefficient is 117,0 W.

The GCI is an especially useful technique that allows obtaining reliable results with a lower number of grids to achieve independence. Therefore, it saves time and computational space. Furthermore, it allows obtaining the error bars at each point, which indicates the reliability of the results. But the immediate selection of the mesh sizes that will yield independence requires a lot of experience, so it is possible that in preliminary explorations it will be necessary to simulate many meshes, as many as in conventional independence studies, until finding those element sizes that will guarantee an appropriate asymptotic result value by Richardson extrapolation.

Even though the difference between the numerical and experimental results is large, the behavior of both curves is similar, and the error between them may be attributed to mechanical losses, as was previously mentioned.

For future works, the corrections will be applied to the bench to reduce the error associated with mechanical losses. The simulation will also be calibrated so that it considers some factors that it currently does not consider and that are unavoidable in the experiment.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)